164 Late Adult Lifestyles

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

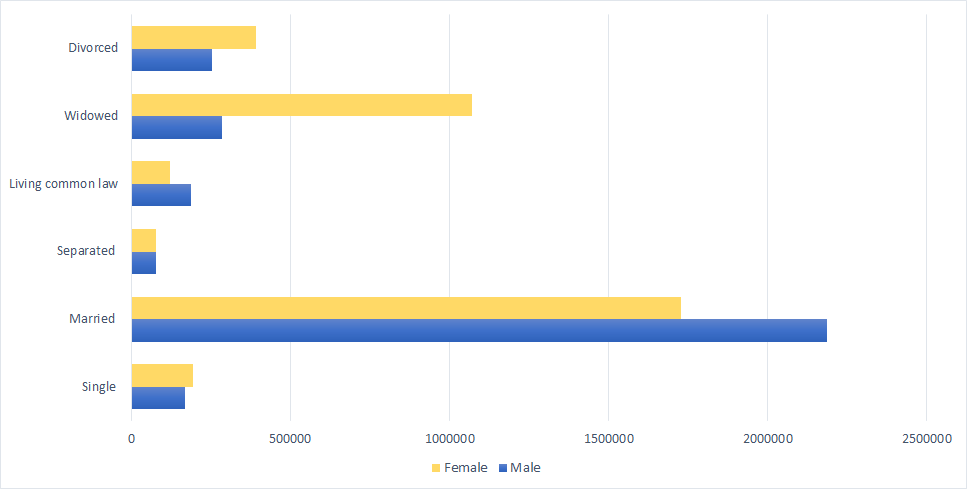

Marriage: As can be seen in Figure 9.39, the most common living arrangement for older adults in 2021 was marriage (Statistics Canada, 2022). Although this was more common for older men.

Widowhood: Losing one’s spouse is one of the most difficult transitions in life. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, commonly known as the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory, rates the death of a spouse as the most significant stressor (Holmes and Rahe, 1967). The loss of a spouse after many years of marriage may make an older adult feel adrift in life. They must remake their identity after years of seeing themselves as a husband or wife. Approximately, 1 in 3 women aged sixty-five and older are widowed, compared with about 1 in 10 men.

Loneliness is the biggest challenge for those who have lost their spouse (Kowalski and Bondmass, 2008). However, several factors can influence how well someone adjusts to this life event. Older adults who are more extroverted (McCrae and Costa, 1988) and have higher self-efficacy (Carr, 2004b) often fare better. Positive support from adult children is also associated with fewer symptoms of depression and better overall adjustment in the months following widowhood (Ha, 2010).

The context of the death is also an important factor in how people may react to the death of a spouse. The stress of caring for an ill spouse can result in a mixed blessing when the ill partner dies (Erber and Szchman, 2015). The death of a spouse who died after a lengthy illness may come as a relief for the surviving spouse, who may have had the pressure of providing care for someone who was increasingly less able to care for themselves. At the same time, this sense of relief may be intermingled with guilt for feeling relief at the passing of their spouse. The emotional issues of grief are complex and will be discussed in more detail in chapter ten.

Widowhood also poses health risks. The widowhood mortality effect refers to the higher risk of death after the death of a spouse (Sullivan and Fenelon, 2014). Subramanian, Elwert, and Christakis (2008) found that widowhood increases the risk of dying from almost all causes. However, research suggests that the predictability of the spouse’s death plays an important role in the relationship between widowhood and mortality. Elwert and Christakis (2008) found that the rate of mortality for windows and widowers was lower if they had time to prepare for the death of their spouse, such as in the case of a terminal illness like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s diseases. Another factor that influences the risk of mortality is gender. Men show a higher risk of mortality following the death of their spouse if they have higher health problems (Bennett, Hughes, and Smith, 2005). In addition, widowers have a higher risk of suicide than do widows (Ruckenhauser, Yazdani, and Ravaglia, 2007).

Divorce: As noted in chapter eight, older adults are divorcing at higher rates than in prior generations. However, adults age sixty-five and over are still less likely to divorce than middle-aged and young adults (Wu and Schimmele, 2007). Divorce poses a number of challenges for older adults, especially women, who are more likely to experience financial difficulties and are more likely to remain single than are older men (McDonald and Robb, 2004).

However, in both America (Lin, 2008) and England (Glaser, Stuchbury, Tomassini, and Askham, 2008), studies have found that the adult children of divorced parents offer more support and care to their mothers than their fathers. While divorced, older men may be better off financially and are more likely to find another partner, they may receive less support from their adult children.

Dating: Due to changing social norms and shifting cohort demographics, it has become more common for single older adults to be involved in dating and romantic relationships (Alterovitz and Mendelsohn, 2011). An analysis of widows and widowers ages sixty-five and older found that eighteen months after the death of a spouse, 37 percent of men and 15 percent of women were interested in dating (Carr, 2004a). Unfortunately, opportunities to develop close relationships often diminish in later life as social networks decrease because of retirement, relocation, and the death of friends and loved ones (de Vries, 1996). Consequently, older adults, much like those younger, are increasing their social networks using technologies, including e-mail, chat rooms, and online dating sites (Fox, 2004; Wright and Query, 2004).

Interestingly, older men and women parallel online dating information as those younger. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2011) analyzed six hundred internet personal ads from different age groups, and across the lifespan, men sought physical attractiveness and offered status-related information more than women. With advanced age, men desired women increasingly younger than themselves, whereas women desired older men until ages seventy-five and over, when they sought men younger than themselves. Research has previously shown that older women in romantic relationships are not interested in becoming a caregiver or becoming widowed for a second time (Carr, 2004a). Additionally, older men are more eager to re-partner than are older women (Davidson, 2001; Erber and Szuchman, 2015). Concerns expressed by older women included not wanting to lose their autonomy, care for a potentially ill partner, or merging their finances with someone (Watson and Stelle, 2011).

Older dating adults also need to know about threats to sexual health, including being at risk for sexually transmitted diseases, including chlamydia, genital herpes, and HIV. Nearly 25 percent of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are fifty or older (Office on Women’s Health, 2010b). Githens and Abramsohn (2010) found that only 25 percent of adults fifty and over who were single or had a new sexual partner indicated that they have used a condom the last time they had sex. Robin (2010) stated that 40 percent of those fifty and older have never been tested for HIV. These results indicated that educating all individuals, not just adolescents, on healthy sexual behaviour is important.

Remarriage and cohabitation: Older adults who remarry often find that their remarriages are more stable than those of younger adults. Kemp and Kemp (2002) suggest that greater emotional maturity may lead to more realistic expectations regarding marital relationships, leading to greater stability in remarriages in later life. Older adults are also more likely to be seeking companionship in their romantic relationships. Carr (2004a) found that older adults who have considerable emotional support from their friends were less likely to seek romantic relationships. In addition, older adults who have divorced often desire the companionship of intimate relationships without marriage. As a result, cohabitation is increasing among older adults, and like remarriage, cohabitation in later adulthood is often associated with more positive consequences than it is in younger age groups (King and Scott, 2005). No longer being interested in raising children, and perhaps wishing to protect family wealth, older adults may see cohabitation as a good alternative to marriage. In 2014, 2 percent of adults age sixty-five and up were cohabitating (Stepler, 2016b).

Media Attributions

- Figure 9 39 © Dinesh Ramoo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license