128 Climacteric

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

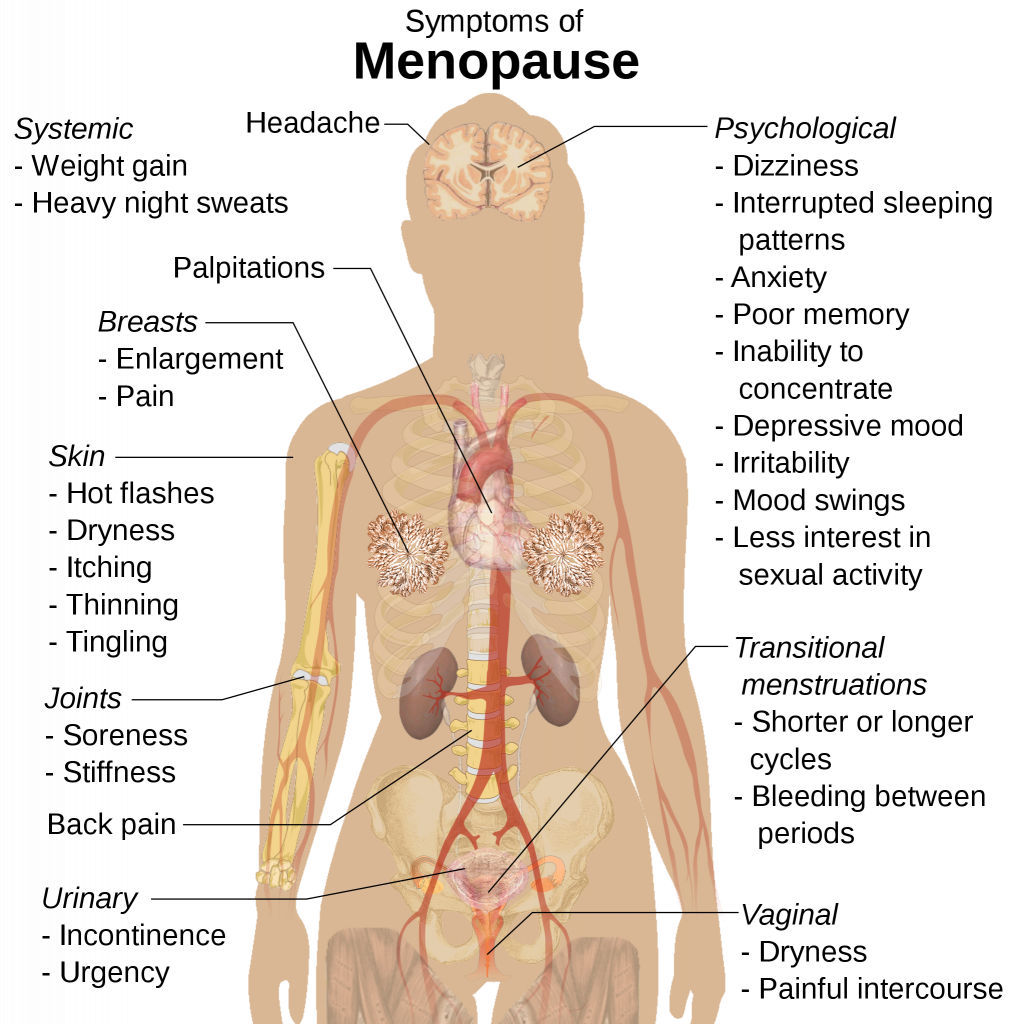

Figure 8.12 identifies symptoms experienced by women during menopause; however, women vary greatly in the extent to which these symptoms are experienced. Most American women go through menopause with few problems (Carroll, 2016). Overall, menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004).

Hormone-replacement therapy: Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement has changed the frequency with which estrogen-replacement and hormone-replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen-replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. However, more recently, hormone-replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (National Institutes of Health, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen-replacement or hormone-replacement therapy. If so, they can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Menopause and ethnicity: In a review of studies that mentioned menopause, symptoms varied greatly across countries, geographic regions, and even across ethnic groups within the same region (Palacios, Henderson, and Siseles, 2010). For example, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) examined 14,906 white, African American, Hispanic, Japanese American, and Chinese American women’s menopausal experiences (Avis et al., 2001). After controlling for age, educational level, general health status, and economic stressors, white women were more likely to disclose symptoms of depression, irritability, forgetfulness, and headaches compared to women in the other racial/ethnic groups. African American women experienced more night sweats, but this varied across research sites. Finally, Chinese American and Japanese American reported fewer menopausal symptoms when compared to the women in the other groups. Overall, the Chinese and Japanese group reported the fewest symptoms, while white women reported more psychosomatic symptoms and African American women reported more vasomotor symptoms.

Cultural differences: Cultural influences seem to also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. Further, the prevalence of language specific to menopause is an important indicator of the occurrence of menopausal symptoms in a culture. Hmong tribal women living in Australia and Mayan women report that there is no word for “hot flashes” and both groups did not experience these symptoms (Yick-Flanagan, 2013). When asked about physical changes during menopause, the Hmong women reported lighter or no periods. They also reported no emotional symptoms and found the concept of emotional difficulties caused by menopause amusing (Thurston and Vissandjee, 2005). Similarly, a study with First Nations women in Canada found there was no single word for “menopause” in the Oji-Cree or Ojibway languages, with women referring to menopause only as “that time when periods stop” (Madden, St Pierre-Hansen, and Kelly, 2010).

While some women focus on menopause as a loss of youth, womanhood, and physical attractiveness, career-oriented women tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Japanese women perceive menopause as a transition from motherhood to a more whole person, and they no longer feel obligated to fulfill certain expected social roles, such as the duty to be a mother (Kagawa-Singer, Wu, and Kawanishi, 2002). In India, 94 percent of women said they welcomed menopause. Aging women gain status and prestige and no longer have to go through self-imposed menstrual restrictions, which may contribute to Indian women’s experiences (Kaur, Walia, and Singh, 2004). Overall, menopause signifies many different things to women around the world and there is no typical experience. Further, normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause is supported by research and women’s experiences.

Male sexual and reproductive health: Although men can continue to father children throughout middle adulthood, erectile dysfunction (ED) becomes more common. ED refers to the inability to achieve an erection or an inconsistent ability to achieve an erection (Swierzewski, 2015). Intermittent ED affects as many as 50 percent of men between the ages of forty and seventy. About 30 million men in the United States experience chronic ED, and the percentages increase with age. Approximately 4 percent of men in their forties, 17 percent of men in their sixties, and 47 of men older than seventy-five experience chronic ED.

Causes for ED are primarily due to medical conditions, including diabetes, kidney disease, alcoholism, and atherosclerosis (a build-up of plaque in the arteries). Plaque is made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances found in the blood. Over time, plaque builds up, hardens, and restricts the blood flow in the arteries (National Institutes of Health, 2014d). This build-up limits the flow of oxygenated blood to organs and the penis. Overall, diseases account for 70 percent of chronic ED, while psychological factors, such as stress, depression, and anxiety account for 10 to 20 percent of all cases. Many of these causes are treatable, and ED is not an inevitable result of aging.

Men during middle adulthood may also experience prostate enlargement, which can interfere with urination, and deficient testosterone levels, which decline throughout adulthood, but especially after age fifty. When testosterone levels decline significantly, it is referred to as andropause or late-onset hypogonadism. Identifying whether testosterone levels are low is difficult because individual blood levels vary greatly. Low testosterone is not a concern unless it accompanied by negative symptoms such as low sex drive, ED, fatigue, loss of muscle, loss of body hair, or breast enlargement. Low testosterone is also associated with medical conditions such as diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, and testicular cancer. The effectiveness of supplemental testosterone is mixed, and long-term testosterone-replacement therapy for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer, blood clots, heart attack, and stroke (WebMD, 2016). Most men with low testosterone do not have related problems (Berkeley Wellness, 2011).

The Climacteric and Sexuality

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age, and many older adults are very interested in staying sexually active (Dimah and Dimah, 2004). According to the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) (Center for Sexual Health Promotion, 2010), 74 percent of men and 70 percent of women aged forty to forty-nine engaged in vaginal intercourse during the previous year, while 58 percent of men and 51 percent of women aged fifty to fifty-nine did so.

Despite these percentages indicating that middle adults are sexually active, age-related physical changes can affect sexual functioning. For women, decreased sexual desire and pain during vaginal intercourse because of menopausal changes have been identified (Schick et al., 2010). A woman may also notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal, which can affect overall pleasure (Carroll, 2016). Men may require more direct stimulation for an erection and the erection may be delayed or less firm (Carroll, 2016). As previously discussed, men may experience erectile dysfunction or experience medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning. Couples can continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse.

Risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least twelve months, however, couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. In 2014, 16.7 percent of new HIV diagnoses (7,391 of 44,071) in the US were among people fifty and older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014e). This was an increase from 15.4 percent in 2005. Practicing safe sex is important at any age, but unfortunately adults over the age of forty have the lowest rates of condom use (Center for Sexual Health Promotion, 2010). This low rate of condom use suggests the need to enhance education efforts for older individuals regarding STI risks and prevention. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

Media Attributions

- Figure 8 12 © Mikael Häggström is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8.13: Symptoms of menopause vary greatly. © A Vahanvaty is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8 14 © Mxcil is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Old Couple © Ian MacKenzie is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license