111 Education and Career

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

According to the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (2016a), in the United States about 84 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds have a high school diploma or GED. Nearly 9 out of every 10 adults aged twenty-five and older (88 percent) in the United States have a high school diploma or its equivalent (Ryan and Bauman, 2016). College is an important aspect of the lives of many young adults in the United States, with 36 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds (National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, 2016b) and 7 percent of 25- to 49-year-olds attending college (National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, 2016c). More than half of those twenty-five and older (59 percent) have completed some college, and 1 in 3 (32.5 percent) have a bachelor’s degree or higher, with slightly more women (33 percent) than men (32 percent) holding a college degree (Ryan and Bauman, 2016). Fifty-six percent of four-year college students earn a bachelor’s degree within six years (National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, 2016d).

The rate of college attainment has grown more slowly in the United States than in a number of other nations in recent years (OCED, 2014). This may be due to fact that the cost of attaining a degree is higher in the US than in many other nations. Statistics Canada indicates that about half of all Canadian college graduates have some form of student debt. This is about 1.7 million borrowers. As of 2022, the average student loan in Canada grew by 3.5 percent from 2019. Canadian undergraduates spent an average of $6,693 on tuition for the 2021–2022 academic year. Canada introduced a student debt relief program in 2020 increasing the grant for full-time students to $6,000 and part-time students to $3,600. As interest on student loans does not accumulate before graduation in Canada, student debt has not reached the level of crisis it is in the United States.

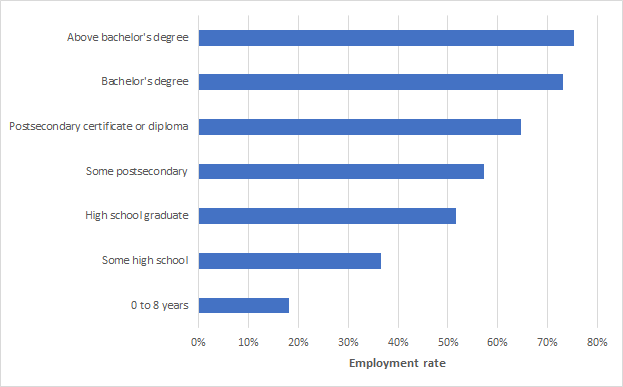

Is college worth the time and investment? College is certainly a substantial investment each year, with the financial burden falling on students and their families in the US, and mainly by the government in many other nations. Nonetheless, the benefits both to the individual and the society outweighs the initial costs. As can be seen in Figure 7.16, those in Canada with the most advanced degrees have the highest rate of employment.

Worldwide, over 80 percent of college-educated adults are employed, compared with just over 70 percent of those with a high school or equivalent diploma, and only 60 percent of those with no high school diploma (OECD, 2015). Those with a college degree will earn more over the course of their life time. Moreover, the benefits of college education go beyond employment and finances. The The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that, around the world, adults with higher educational attainment were more likely to volunteer, felt they had more control over their lives, and thus were more interested in the world around them. Studies of US college students find that they gain a more distinct identity and become more socially competent and less dogmatic and ethnocentric compared to those not in college (Pascarella, 2006).

Career Development and Employment

Work plays a significant role in the lives of people, and emerging and early adulthood is the time when most of us make choices that will establish our careers. Career development has a number of stages:

- Stage one: As children we may select careers based on what appears glamorous or exciting to us (Patton and McMahon, 1999). There is little regard in this stage for whether we are suited for our occupational choices.

- Stage two: In the second stage, teens include their abilities and limitations, in addition to the glamour of the occupation, when narrowing their choices.

- Stage three: Older teens and emerging adults narrow their choices further and begin to weigh more objectively the requirements, rewards, and downsides to careers, along with comparing possible careers with their own interests, values, and future goals (Patton and McMahon, 1999). However, some young people in this stage fall into careers simply because they were what were available at the time, because of family pressures to pursue particular paths, or because they were high-paying jobs, rather than from an intrinsic interest in that career path (Patton and McMahon, 1999).

- Stage four: Super (1980) suggests that by our mid- to late thirties, many adults settle in their careers. Even though they might change companies or move up in their position, there is a sense of continuity and forward motion in their career. However, some people at this point in their working life may feel trapped, especially if there is little opportunity for advancement in a more dead-end job.

How have things changed for Millennials compared with previous generations of early adults? In recent years, young adults are more likely to find themselves job-hopping, and periodically returning to school for further education and retraining than in prior generations. However, researchers find that occupational interests remain fairly stable. Thus, despite the more frequent change in jobs, most people are generally seeking jobs with similar interests rather than entirely new careers (Rottinghaus, Coon, Gaffey, and Zytowski, 2007).

Recent research also suggests that Millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) are looking for something different in their place of employment. According to a recent Gallup poll report (2016), Millennials want more than a paycheque; they want a purpose. Unfortunately, only 29 percent of Millennials surveyed by Gallup reported that they were “engaged” at work. In fact, they report being less engaged than Gen Xers (those born between 1965 and 1980) and Baby Boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964); with 55 percent of Millennials saying they are not engaged at all with their job. This indifference to their workplace may explain the greater tendency to switch jobs. With their current job giving them little reason to stay, they are more likely to take any new opportunity to move on. Only half of Millennials saw themselves working at the same company a year later. Gallup estimates that this employment turnover and lack of engagement costs businesses $30.5 billion a year.

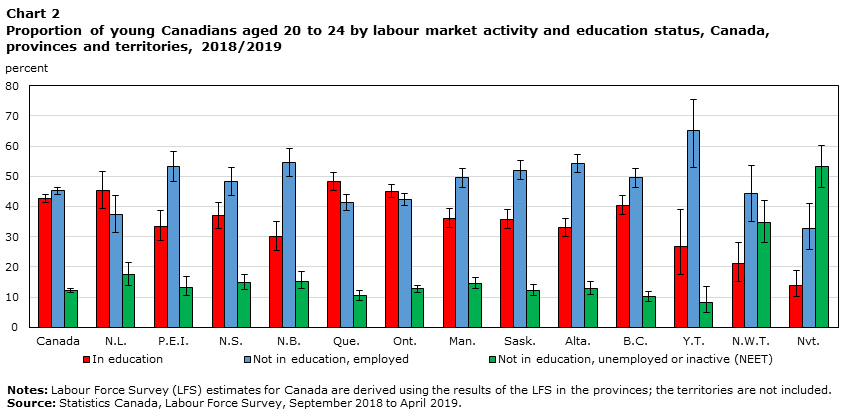

NEETs: Around the world, teens and young adults were some of the hardest hit by the economic downturn in recent years (Desilver, 2016). Consequently, a number of young people have become NEETs, neither employed nor in education or training. While the number of young people who are NEETs has declined, there is concern that “without assistance, economically inactive young people won’t gain critical job skills and will never fully integrate into the wider economy or achieve their full earning potential” (Desilver, 2016, para. 3). In Canada, the NEET rate for Canadians aged fifteen to twenty-nine was 12 percent in February 2020. This rate rose to 18 percent in March of that year (when COVID-19 pandemic measures were put in place). It increased again to 24 percent in April 2020, the highest in twenty years. In Europe, where the rates of NEETs are persistently high, there is also concern that having such large numbers of young adults with little opportunity may increase the chances of social unrest.

In 2015 in the United States, nearly 17 percent of 16- to 29-year-olds were neither employed nor in school, according to data Desilver (2016) obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is down slightly from 2013, when approximately 18.5 percent of this age group fit the category. In the United States, NEETs are more likely to be women than men, most NEETs have an education level of high school or less, and Asians are less likely to be NEETs than any other ethnic group.

The rate of NEETs varies in European nations, with higher rates found in nations that have been the hardest hit by economic recessions and government austerity measures. For example, more than 25 percent of those aged fifteen to twenty-nine in Greece and Italy are NEETs. In contrast, countries less affected by an economic downturn, such as Denmark, had much lower rates (7.3 percent).

What role does gender play on career and employment? Gender also has an impact on career choices. Despite the rise in the number of women who work outside of the home, there are some career fields that are still pursued more by men than women. Jobs held by women still tend to cluster in the service sector, such as education, nursing, and childcare, while in more technical and scientific careers women are greatly outnumbered by men. Jobs that have been traditionally held by women tend to have lower status, pay, benefits, and job security (Ceci and Williams, 2007).

In recent years, women have made inroads into fields once dominated by men, and today women are almost as likely as men to become medical doctors or lawyers. Despite these changes, women are more likely to have lower status, and thus less pay than men in these professions. For instance, women are more likely to be a family practice doctor than a surgeon, or are less likely to make partner in a law firm (Ceci and Williams, 2007).

Sexism

Sexism or gender discrimination is prejudice or discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender. Sexism can affect any sex that is marginalized or oppressed in a society; however, it is particularly documented as affecting women and girls. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles and includes the belief that men and boys are intrinsically superior to other sexes and genders. Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence.

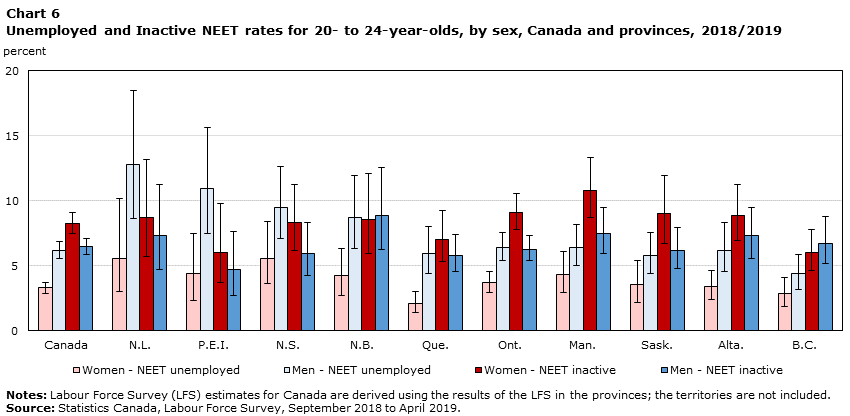

As seen in Figure 7.18, NEET rates for women do not differ significantly between men and women. However, in six of the ten Canadian provinces, NEET women are likely to be inactive. In four of the provinces, men are more likely to be unemployed. Only Ontario has significantly higher rates of inactive female NEETs. NEET rates are more pronounced during ages twenty-five to twenty-nine, where motherhood is more prevalent.

Sexism can exist on a societal level, such as in hiring, employment opportunities, and education. In the United States, women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions, such as engineering, aviation, and construction (Blau, Ferber, and Winkler, 2010; Ceci and Williams, 2011). In many areas of the world, young girls are not given the same access to nutrition, healthcare, and education as boys. Sexism also includes people’s expectations of how members of a gender group should behave. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing; when a woman behaves in an unfriendly or assertive manner, she may be disliked or perceived as aggressive because she has violated a gender role (Rudman, 1998). In contrast, a man behaving in a similarly unfriendly or assertive way might be perceived as strong or may even gain them respect in some circumstances.

Occupational sexism involves discriminatory practices, statements, or actions based on a person’s sex that occur in the workplace. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination. In 2008, the OECD found that while female employment rates have expanded, and gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed nearly everywhere, on average women still have a 20 percent less chance to have a job. The Council of Economic Advisors (2015) found that despite women holding 49.3 percent of the jobs, they are paid only $0.78 for every $1.00 a man earns. It also found that despite the fact that many countries, including the US, have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce. In the US, women account for 47 percent of the overall labour force, yet they make up only 6 percent of corporate CEOs and top executives. Some researchers see the root cause of this situation in the tacit discrimination based on gender that is conducted by current top executives and corporate directors (who are primarily male).

Media Attributions

- Figure 7 16 © Dinesh Ramoo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7 17 © Statistics Canada is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 7 18 © Statistics Canada is licensed under a Public Domain license