109 Sexuality

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest themselves in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual response cycle and the basic biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals that are expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality also impacts and is impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

The sexual response cycle: Sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. This motivation is determined by biological, psychological, and social factors. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability to engage in sexual behaviours. However, sex hormones do not directly regulate the ability to copulate in primates (including humans); rather, they are only one influence on the motivation to engage in sexual behaviours. Social factors, such as work and family, also have an impact, as do internal psychological factors like personality and stress. Sex drive may also be affected by hormones, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle stress, pregnancy, and relationship issues.

The sexual response cycle is a model that describes the physiological responses that take place during sexual activity. According to Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948), the cycle consists of four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. The excitement phase is the phase in which the intrinsic (inner) motivation to pursue sex arises. The plateau phase is the period of sexual excitement with increased heart rate and circulation that sets the stage for orgasm. Orgasm is the release of tension, and the resolution period is the unaroused state before the cycle begins again.

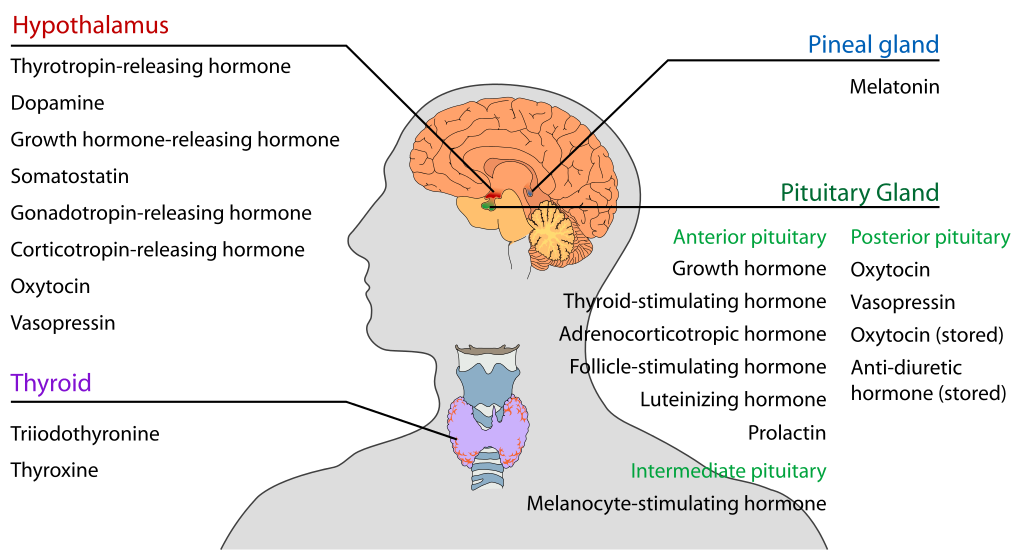

The brain and sex: The brain is the structure that translates the nerve impulses from the skin into pleasurable sensations. It controls nerves and muscles used during sexual behaviour. The brain regulates the release of hormones, which are believed to be the physiological origin of sexual desire. The cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain that allows for thinking and reasoning, is believed to be the origin of sexual thoughts and fantasies. Beneath the cortex is the limbic system, which consists of the amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and septal area. These structures are where emotions and feelings are believed to originate, and are important for sexual behaviour.

The hypothalamus is the most important part of the brain for sexual functioning. This is the small area at the base of the brain consisting of several groups of nerve-cell bodies that receives input from the limbic system. Studies with lab animals have shown that destruction of certain areas of the hypothalamus causes complete elimination of sexual behaviour. One of the reasons for the importance of the hypothalamus is that it controls the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control the other glands of the body.

Hormones: Several important sexual hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin, also known as the hormone of love, is released during sexual intercourse when an orgasm is achieved. Oxytocin is also released in females when they give birth or are breast feeding; it is believed that oxytocin is involved with maintaining close relationships. Both prolactin and oxytocin stimulate milk production in females. Follicle-stimulating hormone is responsible for ovulation in females by triggering egg maturity; it also stimulates sperm production in males. Luteinizing hormone triggers the release of a mature egg in females during the process of ovulation.

In males, testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation. Vasopressin is involved in the male arousal phase, and the increase of vasopressin during erectile response may be directly associated with increased motivation to engage in sexual behaviour.

The relationship between hormones and female sexual motivation is not as well understood, largely due to the overemphasis on male sexuality in Western research. Estrogen and progesterone typically regulate motivation to engage in sexual behaviour for females, with estrogen increasing motivation and progesterone decreasing it. The levels of these hormones rise and fall throughout a woman’s menstrual cycle. Research suggests that testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships.

Sexual responsiveness peak: Men and women tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. For men, sexual responsiveness tends to peak in the late teens and early twenties. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness begins a slow decline in the late twenties and into the thirties, although a man may continue to be sexually active. Through time, a man may require more intense stimulation in order to become aroused. Women often find that they become more sexually responsive throughout their twenties and thirties and may peak in the late thirties or early forties. This is likely due to greater self-confidence and reduced inhibitions about sexuality.

Sexually transmitted infections: Sometimes referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal diseases (VDs), sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are illnesses that have a significant probability of transmission by means of sexual behaviour, including vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex. Some STIs can also be contracted by sharing intravenous drug needles with an infected person, as well as through childbirth or breastfeeding.

Common STIs include:

- chlamydia;

- herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2);

- human papilloma virus (HPV);

- gonorrhea;

- syphilis;

- trichomoniasis;

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014), there was an increase in the three most common types of STDs in 2014. These include 1.4 million cases of chlamydia, 350,000 cases of gonorrhea, and 20,000 cases of syphilis. Those most affected by STIs are younger women and gay/bisexual men. The most effective way to prevent transmission of STIs is to practice safe sex and avoid direct contact of skin or fluids, which can lead to transfer with an infected partner. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as male condoms, female condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers.

Societal views on sexuality: Society’s views on sexuality are influenced by everything from religion to philosophy, and they have changed throughout history and are continuously evolving. Historically, religion has been the greatest influence on sexual behaviour in the United States; however, in more recent years, peers and the media have emerged as two of the strongest influences, particularly among American teens (Potard, Courtois, and Rusch, 2008).

Mass media in the form of television, magazines, movies, and music continues to shape what is deemed appropriate or normal sexuality, targeting everything from body image to products meant to enhance sex appeal. Media serves to perpetuate a number of social scripts about sexual relationships and the sexual roles of men and women, many of which have been shown to have both empowering and problematic effects on people’s (especially women’s) developing sexual identities and sexual attitudes.

Cultural differences: In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In Canada, the United States, and northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties, when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three-fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age twenty, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield and Rapson, 2006).

Sexual orientation: A person’s sexual orientation is their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular sex or gender. It is a personal quality that inclines people to feel romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to people of a given sex or gender. According to the American Psychological Association (2016), sexual orientation also refers to a person’s sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviours, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions.

Sexual orientation on a continuum: Sexuality researcher Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey et al. (1948) created a seven-point rating scale that ranged from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Research done over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016).

However, sexual orientation now can be defined in many ways. Heterosexuality, which is often referred to as being straight, is attraction to individuals of the opposite sex/gender, while homosexuality, being gay or lesbian, is attraction to individuals of one’s own sex/gender. Bisexuality was a term traditionally used to refer to attraction to individuals of either male or female sex, but it has recently been used in nonbinary models of sex and gender (models that do not assume there are only two sexes or two genders) to refer to attraction to any sex or gender. Alternative terms such as pansexuality and polysexuality have also been developed, referring to attraction to all sexes/genders and attraction to multiple sexes/genders, respectively (Carroll, 2016).

Asexuality refers to having no sexual attraction to any sex/gender. According to Bogaert (2015) about 1 percent of the population is asexual. Being asexual is not due to any physical problems, and the lack of interest in sex does not cause the individual any distress. Asexuality is being researched as a distinct sexual orientation.

Development of sexual orientation: According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence. However, this is not always the case, and some do not become aware of their sexual orientation until much later in life. It is not necessary to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Some researchers argue that sexual orientation is not static and inborn, but is instead fluid and changeable throughout the lifespan.

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. Research has examined possible biological, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to one factor (American Psychological Association, 2016). Biological explanations, that include genetics, hormones, and birth order, will be explored further.

Using both twin and familial studies, heredity provides one biological explanation for sexual orientation. Bailey and Pillard (1991) studied pairs of male twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins was 52 percent, while the rate for fraternal twins was only 22 percent. Bailey, Pillard, Neale, and Agyei (1993) studied female twins and found a similar difference with a concordance rate of 48 percent for identical twins and 16 percent for fraternal twins. Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger, and Sanders (2010) found that gay men had more homosexual male relatives than heterosexual men, and sisters of gay men were more likely to be lesbians than sisters of straight men.

Excess or deficient exposure to hormones during prenatal development has also been theorized as an explanation for sexual orientation. One-third of females exposed to abnormal amounts of prenatal androgens, a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), identify as bisexual or lesbian (Cohen-Bendahan, van de Beek, and Berenbaum, 2005). In contrast, too little exposure to prenatal androgens may affect male sexual orientation by not masculinizing the male brain (Carlson, 2011).

Another explanation attempts to explain why gay men tend to have a greater number of older brothers than heterosexual men (Blanchard, 2001). This difference is explained by the maternal immune hypothesis which proposes “a progressive immunization to male-specific antigens after the birth of successive sons in some mothers, which increases the effect of anti-male antibodies on the sexual differentiation of the brain in the developing fetus” (Carroll, 2016, p. 264). Consequently, in some families with multiple brothers, those born later have demonstrated higher rates of homosexuality.

Sexual orientation discrimination: Canada is heteronormative, meaning that society supports heterosexuality as the norm. Consider, for example, that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know you were straight?” (Ryle, 2011). Living in a culture that privileges heterosexuality has a significant impact on the ways in which non-heterosexual people are able to develop and express their sexuality.

Open identification of one’s sexual orientation may be hindered by homophobia, which encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). It can be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, or hatred; it may be based on irrational fear and is sometimes related to religious beliefs (Carroll, 2016). Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behaviour, such as discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual orientations that are non-heterosexual. Recognized types of homophobia include institutionalized homophobia, such as religious and state-sponsored homophobia, and internalized homophobia in which people with same-sex attractions internalize, or believe, society’s negative views and/or hatred of themselves.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people regularly experience stigma, harassment, discrimination, and violence based on their sexual orientation (Carroll, 2016). Research has shown that gay, lesbian, and bisexual teenagers are at a higher risk of depression and suicide due to exclusion from social groups, rejection from peers and family, and negative media portrayals of the LGBT community (Bauermeister et al., 2010). Discrimination can occur in the workplace, in housing, at schools, and in numerous public settings. Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes and misinformation. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only come into effect in Canada in the last few years.

The majority of empirical and clinical research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations are done with largely white, middle-class, well-educated samples. This demographic limits our understanding of more marginalized sub-populations that are also affected by racism, classism, and other forms of oppression. In Canada, non-Caucasian LGBT individuals may find themselves in a double minority, in which they are not fully accepted or understood by Caucasian LGBT communities, and are also not accepted by their own ethnic group (Tye, 2006). Many people experience racism in the dominant LGBT community where racial stereotypes merge with gender stereotypes.

Media Attributions

- Figure 7 13a © Casa Fragma is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7 13b © Emily Walker is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7 14 © Narek75 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7 15 © Elvert Barnes is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license