119 Parenthood

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

Parenthood is undergoing changes in Canada and elsewhere in the world. Children are less likely to be living with both parents, and women in Canada have fewer children than they did previously. According to Statistics Canada (2022), fertility rates fell from 1.47 children per woman in 2019 to just 1.4 in 2020. These rates have been declining since 2009 in Canada with the lowest in British Columbia and Nova Scotia. Not only are parents having fewer children, the context of parenthood has also changed. Parenting outside of marriage has increased dramatically among most socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups, although college-educated women are substantially more likely to be married at the birth of a child than are mothers with less education (Dye, 2010). The average fertility rate of women in the United States was about seven children in the early 1900s and has remained relatively stable at 2.1 since the 1970s (Hamilton, Martin, and Ventura, 2011; Martinez, Daniels, and Chandra, 2012).

People are having children at older ages, too. This is not surprising given that many of the age markers for adulthood have been delayed, including marriage, completing education, establishing oneself at work, and gaining financial independence. In 2014 the average age for American first-time mothers was 26.3 years (CDC, 2015a). The birth rate for women in their early twenties has declined in recent years, while the birth rate for women in their late thirties has risen. In 2011, 40 percent of births were to women ages thirty and older. For Canadian women, birth rates are even higher for women in their late thirties than in their early twenties. In 2011, 52 percent of births were to women ages thirty and older, and the average first-time Canadian mother was 28.5 years old (Cohn, 2013). Improved birth-control methods have also enabled women to postpone motherhood. Despite the fact that young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in life (Wang and Taylor, 2011).

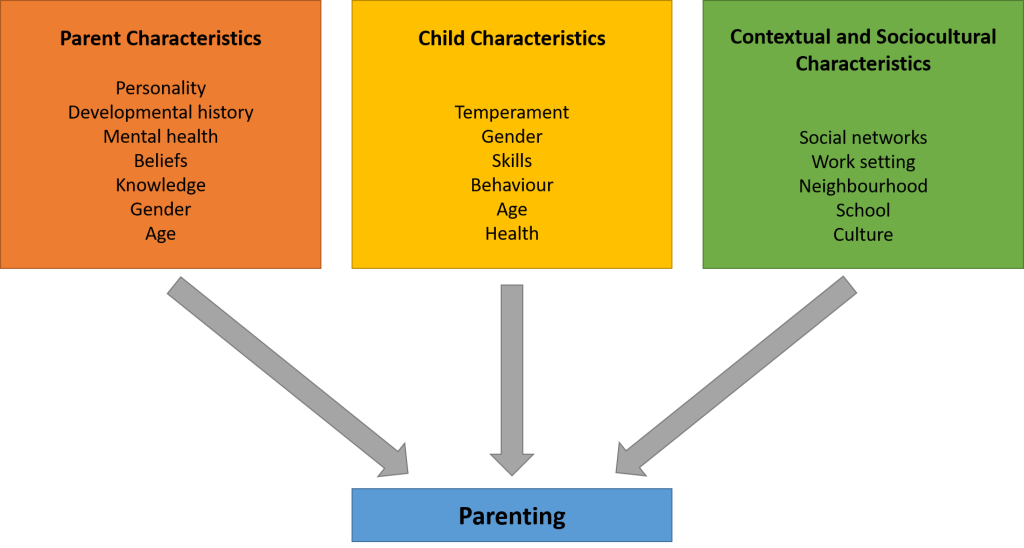

Influences on parenting: Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parenting include: parent characteristics, child characteristics, and contextual can sociocultural characteristics (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Parent characteristics: Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the age of the parent, gender, beliefs, personality, developmental history, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviours. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie, Stams, Dekovic, Reijntes, and Belsky, 2009). Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children.

Parents’ developmental histories, or their experiences as children, also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their own parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth were more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their own children (Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, and Owen, 2009). Patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their own parents’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods with their own children.

Child characteristics: Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, children influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviours and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark, Kochanska, and Ready, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff, Lengua, and Zalewski, 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde, Else-Quest, and Goldsmith, 2004). Thus, child temperament, as previously discussed in chapter three, is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn (Grusec, Goodnow, and Cohen, 1996). Parents also talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotion words with their daughters (Crowley, Callanan, Tenenbaum, and Allen, 2001).

Contextual factors and sociocultural characteristics: The parent–child relationship does not occur in isolation. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighbourhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger and Conger, 2002). Culture also influences parenting behaviours in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). Parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, maintaining harmonious relationships, and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. Other important contextual characteristics, such as neighbourhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings do not always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). Culture is also a contributing contextual factor, as discussed previously in chapter four. For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighbourhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011). The different influences are shown in Figure 7.30.

Media Attributions

- Figure 7 28 © TEBOMSW is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7 29 © John Hill is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7 30 © Dinesh Ramoo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license