113 Attachment in Young Adulthood

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (Table 7.4).

| Secure | I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

| Avoidant | I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others. I find it difficult to trust them completely and allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

| Nervous/Ambivalent | I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

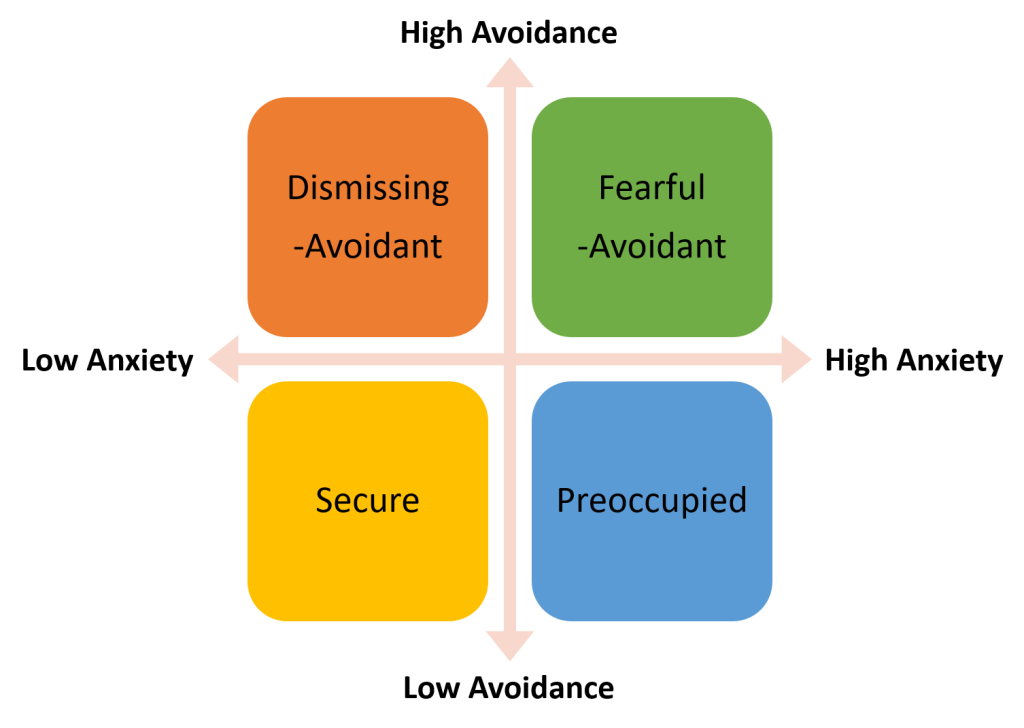

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions: attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley, Hudson, Heffernan, and Segal, 2015). Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults: secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant (see Figure 7.19).

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves, but do not trust others, thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people, and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer and Campbell, 2008; Holland, Fraley, and Roisman, 2012);

- those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, and Kashy, 2005);

- those with avoidant attachments exhibit less support to their partners (Simpson, Rholes, Oriña, and Grich, 2002);

- young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults (Chopik, Edelstein, and Fraley, 2013);

- young adults show more attachment-related avoidance in some studies (Schindler, Fagundes, and Murdock, 2010), while in others middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013); and

- young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles? When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioural qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding; these are the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell and Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with someone who meets their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier, Byer, Fischer, Wright, and DeBord (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than eighty-three heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure, Lydon, Baccus, and Baldwin, 2010). However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson, Fraley, Vicary, and Brumbaugh (2012) found that if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment? The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan and Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, and Holland (2013) found in a sample of more than seven hundred individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age eighteen. Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy using the Strange Situation Technique, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which in turn predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age sixteen, which in turn predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages twenty to twenty-three.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear: Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development. But that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of their early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Relationships with Parents and Siblings

In early adulthood the parent–child relationship has to transition toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults. One of the biggest challenges for parents, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Sibling relationships are one of the longest lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, just as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship later in life. Those who are successful can often move away from the older-younger sibling conflicts of childhood toward a more equal relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to one another in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Erikson: Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson’s (1950, 1968) sixth stage focuses on establishing intimate relationships or risking social isolation. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a lifelong process, as there are periods of identity crisis and stability. However, once identity is established, intimate relationships can be pursued. These intimate relationships include acquaintanceships and friendships, but also the more important close relationships, which are the long-term romantic relationships that we develop with another person, for instance, in a marriage (Hendrick and Hendrick, 2000).

Media Attributions

- Figure 7 19 © Dinesh Ramoo

- Figure 7 20 © Vitold Muratov is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license