Learning Objectives

- Describe how expectant parents prepare for childbirth

- Describe the stages of vaginal delivery

- Explain why a caesarean or induced birth is necessary

- Describe the two common procedures to assess the condition of the newborn

- Describe problems newborns experience before, during, and after birth

Preparation for Childbirth

There are around 389,912 births a year in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2018). Women in Canada give birth in hospitals, at home, or in birthing centres. According to Statistics Canada (2018):

- 6 percent of women of reproductive age have a disability;

- 46 percent of adult women are overweight or obese;

- 27 percent of pregnancies are affected by a chronic illness;

- 3 percent of all births are multiple births;

- 20 percent of all births are among women over age 35;

- 8 percent of infants are born prematurely; and

- 4 percent of total births are affected by a congenital anomaly.

Prepared childbirth refers to being not only in good physical condition to help provide a healthy environment for the baby to develop, but also helping individuals to prepare to accept their new roles as parents. Additionally, parents can receive information and training that will assist them for delivery and life with the baby. The more future parents can learn about childbirth and the newborn, the better prepared they will be for the adjustment they must make to a new life.

One of the most common methods for preparing for childbirth is the Lamaze method. This method originated in Russia and was brought to the United States in the 1950s by Fernand Lamaze. The emphasis of this method is on teaching the woman to be in control in the process of delivery. It includes learning muscle relaxation, breathing though contractions, having a focal point (usually a picture to look at) during contractions, and having a support person who goes through the training process with the mother and serves as a coach during delivery (Eisenberg, Murkoff, and Hathaway, 1996).

Choosing where to have the baby and who will deliver: The vast majority of births occur in a hospital setting. However, 1 percent of women choose to deliver at home (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Curtin, and Mathews, 2015). Women who are at low risk for birth complications can successfully deliver at home. More than half (67 percent) of home deliveries are by certified nurse midwifes. Midwives are trained and licensed to assist in delivery and are far less expensive than the cost of a hospital delivery. However, because of the potential for a complication during the birth process, most medical professionals recommend that delivery take place in a hospital. Despite the concerns, in the United States women who have had previous children, who are over age 25, and who are white are more likely to have out-of-hospital births (MacDorman, Menacker, and Declercq, 2010). In addition to home births, one third of out-of- hospital births occur in freestanding clinics, birthing centers, in physician’s offices, or at other locations.

Stages of Birth for Vaginal Delivery

The first stage of labour begins with uterine contractions that may initially last about thirty seconds and be spaced fifteen to twenty minutes apart. These increase in duration and frequency to more than a minute in length and about three to four minutes apart. Typically, doctors advise that they be called when contractions are coming about every five minutes. Some women experience false labour or Braxton-Hicks contractions, especially with the first child. These may come and go. They tend to diminish when the mother begins walking around. Real labour pains tend to increase with walking. Labour may also be signalled by a bloody discharge being expelled from the cervix. In one out of eight pregnancies, the amniotic sac or water in which the fetus is suspended, may break before labor begins. In such cases, the physician may induce labour with the use of medication if it does not begin on its own in order to reduce the risk of infection. Normally this sac does not rupture until the later stages of labor.

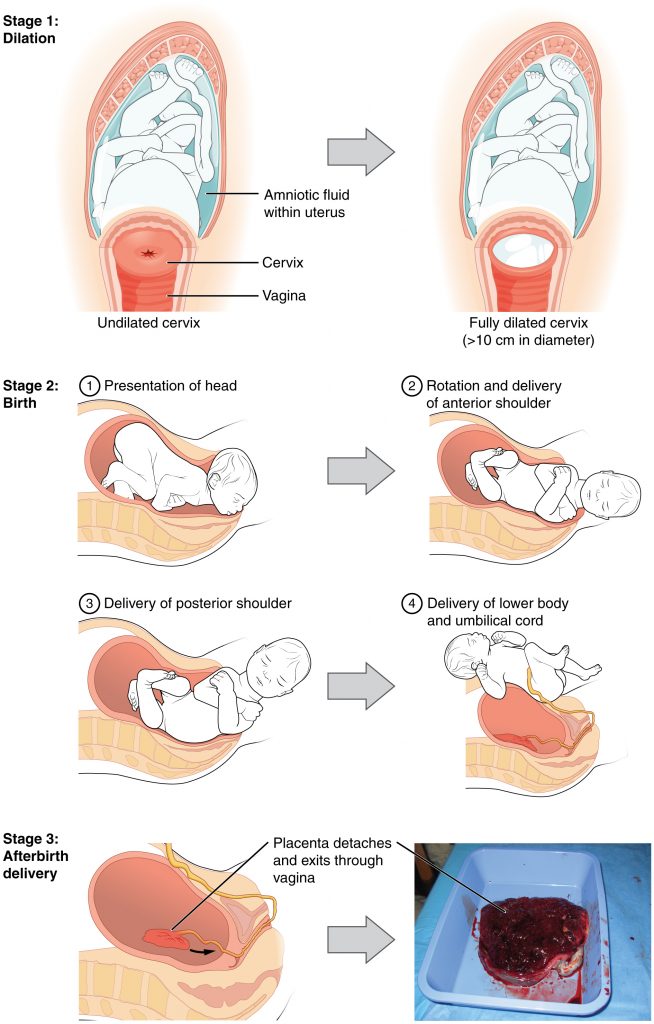

The first stage of labour is typically the longest. During this stage the cervix or opening to the uterus dilates to 10 centimeters or just under 4 inches (See Figure 2.16). This may take around twelve to sixteen hours for first children or about six to nine hours for women who have previously given birth. Labour may also begin with a discharge of blood or amniotic fluid.

The second stage involves the passage of the baby through the birth canal. This stage takes about ten to forty minutes. Contractions usually come about every two to three minutes. The mother pushes and relaxes as directed by the medical staff. Normally the head is delivered first. The baby is then rotated so that one shoulder can come through, followed by the other shoulder. The rest of the baby quickly passes through. At this stage, an episiotomy or incision made in the tissue between the vaginal opening and anus, may be performed to avoid tearing the tissue of the back of the vaginal opening (Mayo Clinic, 2016). The baby’s mouth and nose are suctioned out. The umbilical cord is clamped and cut.

The third stage is relatively painless. During this stage, the placenta or afterbirth is delivered. This is typically within twenty minutes of delivery. If an episiotomy was performed, it is stitched up during this stage.

More than 50 percent of women giving birth at hospitals use an epidural anesthesia during delivery (American Pregnancy Association, 2015). An epidural block is a regional analgesic that can be used during labour and alleviates most pain in the lower body without slowing labour. The epidural block can be used throughout labour and has little to no effect on the baby. Medication is injected into a small space outside the spinal cord in the lower back. It takes ten to twenty minutes for the medication to take effect. An epidural block with stronger medications, such as anesthetics, can be used shortly before a Caesarean section or if a vaginal birth requires the use of forceps or vacuum extraction. Epidural rates have risen from 53.2 percent in 2006–2007 to 57.8 percent in 2015–2016 (Statistics Canada, 2018). A Caesarean section (C-section) is surgery to deliver the baby by removing it through the mother’s abdomen. In the United States, about one in three women have their babies delivered this way (Martin et al., 2015). Most C-sections are done when problems occur during delivery unexpectedly. These can include:

- health problems in the mother;

- signs of distress in the baby;

- not enough room for the baby to pass through the vagina; and

- the position of the baby, such as a breech presentation where the head is not in the downward position.

C-sections are also more common among women carrying more than one baby. Caesarean births have risen from 17.6 percent in 1995–1996 to 27.9 percent in 2015–2016 (Statistics Canada, 2018). Although the surgery is relatively safe for mother and baby, it is considered major surgery and carries health risks. Additionally, it also takes longer to recover from a C-section than from vaginal birth. After healing, the incision may leave a weak spot in the wall of the uterus. This could cause problems with an attempted vaginal birth later. However, more than half of women who have a C-section can give vaginal birth later. Vaginal births after Caesarean (VBAC) have declined dramatically, with the repeat Caesarean birth rate having increased from 64.7 percent in 1995–1996 to 81.0 percent in 2015–2016 (Statistics Canada, 2018).

Induced birth: Sometimes a baby’s arrival may need to be induced or delivered before labour begins. Inducing labour may be recommended for a variety of reasons when there is concern for the health of the mother or baby. For example:

- the mother is approaching two weeks beyond her due date and labour has not started naturally;

- the mother’s water has broken, but contractions have not begun;

- there is an infection in the mother’s uterus;

- the baby has stopped growing at the expected pace;

- there is not enough amniotic fluid surrounding the baby;

- the placenta peels away, either partially or completely, from the inner wall of the uterus before delivery; or

- the mother has a medical condition that might put her or her baby at risk, such as high blood pressure or diabetes (Mayo Clinic, 2014).

Induction rates have risen from 12.9 percent in 1991–1992 to 21.8 percent in 2004–2005 (Statistics Canada, 2018).