179 Cultural Differences in End-of-Life Decisions

Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French

According to Searight and Gafford (2005a), cultural factors strongly influence how doctors, other healthcare providers, and family members communicate bad news to patients, the expectations regarding who makes the healthcare decisions, and attitudes about end-of-life care. In the United States, doctors take the approach that patients should be told the truth about their health. Outside the United States and among certain racial and ethnic groups within the United States, doctors and family members may conceal the full nature of a terminal illness as revealing such information is viewed as potentially harmful to the patient, or at the very least, is seen as disrespectful and impolite. Holland, Geary, Marchini and Tross (1987) found that many doctors in Japan and in numerous African nations used terms such as “mass,” “growth,” and “unclean tissue” rather than referring to cancer when discussing the illness to patients and their families. Family members actively protect terminally ill patients from knowing about their illness in many Hispanic, Chinese, and Pakistani cultures (Kaufert and Putsch, 1997; Herndon and Joyce, 2004).

In the United States, the patient is viewed as autonomous in healthcare decisions (Searight and Gafford, 2005a), while in other nations the family or community plays the main role, or decisions are made primarily by medical professionals or doctors in concert with the family. For instance, in comparison to European Americans and African Americans, Koreans and Mexican Americans are more likely to view family members as the decision makers rather than just the patient (Berger, 1998; Searight and Gafford, 2005a). In many Asian cultures, illness is viewed as a “family event,” not just something that impacts the individual patient (Candib, 2002). Thus, there is an expectation that the family has a say in healthcare decisions. As many cultures attribute high regard and respect for doctors, patients and families may defer some of the end-of-life decision-making to medical professionals (Searight and Gafford, 2005b).

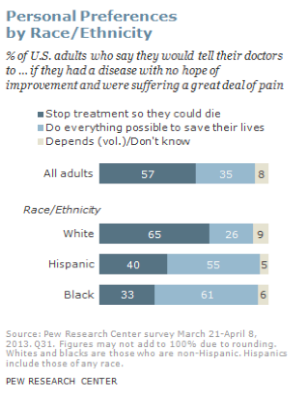

According to a Pew Research Center Survey (Lipka, 2014), while death may not be a comfortable topic to ponder, 37 percent of their survey respondents had given a great deal of thought to their end-of-life wishes, with 35 percent having put these in writing. Yet, over 25 percent had given no thought to this issue. Lipka (2014) also found that there were clear racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life wishes (see Figure 10.10). White people are more likely than Black and Hispanic people to prefer to have treatment stopped if they have a terminal illness. While the majority of Black (61 percent) and Hispanic (55 percent) people prefer that everything be done to keep them alive. Searight and Gafford (2005a) suggest that the low rate of completion of advanced directives among non-white people may reflect a distrust of the US healthcare system as a result of the healthcare disparities non-white people experienced. Among Hispanics, patients may also be reluctant to select a single family member to be responsible for end-of-life decisions out of a concern of isolating the person named and of offending other family members, as this is commonly seen as a “family responsibility” (Morrison, Zayas, Mulvihill, Baskin, and Meier, 1998).