Learning Objectives

- Explain the lifespan perspective and its assumptions about development

- Differentiate periods of human development

- Explain the issues underlying lifespan development

- Identify the historical and contemporary theories impacting lifespan development

Lifespan Perspective

Paul Baltes identified several underlying principles of the lifespan perspective (Baltes, 1987; Baltes, Lindenberger, and Staudinger, 2006). Lifespan theorists believe that development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan. No single age period characterizes or dominates human development. Consequently, the term “lifespan development” will be used throughout the textbook.

Development is multidirectional. Humans change in many directions. We may show gains in some areas of development, while showing losses in other areas. Every change, whether it is finishing high school, getting married, or becoming a parent, entails both growth and loss.

Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains or dimensions: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial. The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness. The cognitive domain encompasses changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language. The psychosocial domain focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends. All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains. For instance, an infant who has started to crawl or walk will encounter more objects and people, thus fostering developmental change in the child’s understanding of the physical and social world.

Development is multidisciplinary. As mentioned at the start of the chapter, human development is such a vast topic of study that it requires the theories, research methods, and knowledge base of many academic disciplines.

Development is characterized by plasticity. Plasticity is all about our ability to change and the malleability of our characteristics. For instance, plasticity is illustrated in the brain’s ability to learn from experience and recover from injury.

Development is multicontextual. Development occurs in many contexts. Baltes (1987) identified three specific contextual influences.

- Normative age-graded influences: An age-grade is a specific age group, such as toddler, adolescent, or senior. Humans in a specific age-grade share particular experiences and developmental changes.

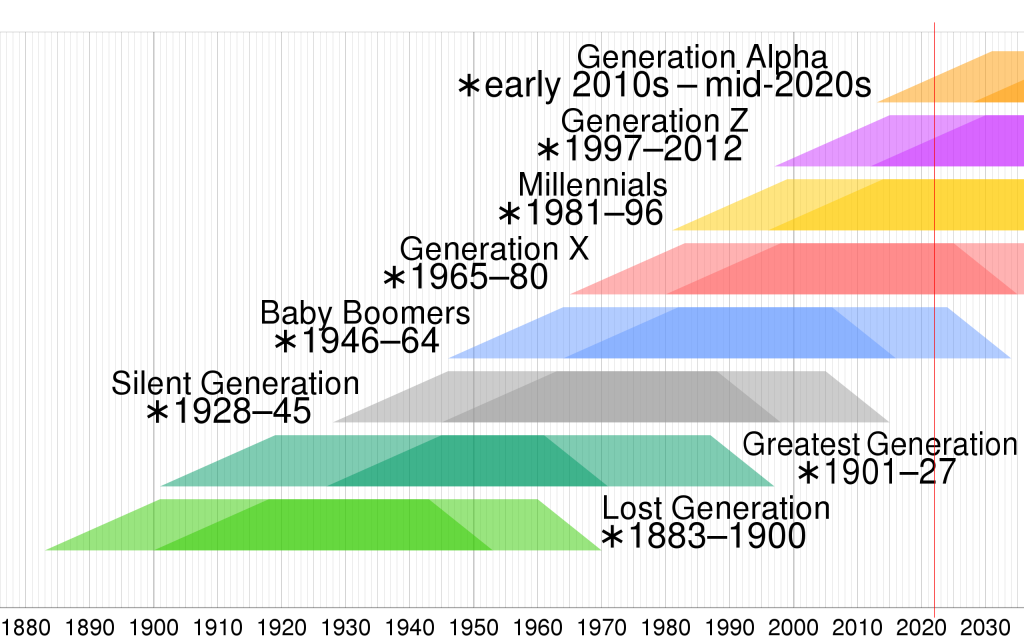

- Normative history-graded influences: The time period in which you are born (Table 1.1) shapes your experiences. A cohort is a group of people who are born at roughly the same period in a particular society. These people travel through life often experiencing similar circumstances.

- Non-normative life influences: Despite sharing an age and history with our peers, each of us also has unique experiences that may shape our development. A child who loses their parent at a young age has experienced a life event that is not typical of the age group.

Another context that influences our lives is our social standing, socioeconomic status, or social class. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a way to identify families and households based on their shared levels of education, income, and occupation. While there is certainly individual variation, members of a social class tend to share similar lifestyles, patterns of consumption, parenting styles, stressors, religious preferences, and other aspects of daily life. All of us born into a class system are socially located and may move up or down depending on a combination of both socially and individually created limits and opportunities.

Families with higher socioeconomic status usually are in occupations (such as attorneys, physicians, executives) that not only pay better, but also grant them a certain degree of freedom and control over their job. Having a sense of autonomy or control is a key factor in experiencing job satisfaction, personal happiness, and ultimately health and well-being (Weitz, 2007). Those families with lower socioeconomic status are typically in occupations that are more routine, more heavily supervised, and require less formal education. These occupations are also more subject to job disruptions, including lay-offs and lower wages.

Poverty level is an income amount established by the federal government that is based on a set of income thresholds that vary by family size (United States Census Bureau, 2016). If a family’s income is less than the government threshold, that family is considered to be living in poverty. Those living at or near poverty level may find it extremely difficult to sustain a household with this amount of income. Poverty is associated with poorer health and a lower life expectancy due to poorer diet, less access to healthcare, greater stress, working in more dangerous occupations, higher infant mortality rates, poorer prenatal care, greater iron deficiencies, greater difficulty in school, and many other problems. Members with higher income status may fear losing that status, but those with lower income status may have greater concerns over losing housing.

Today we are more aware of the variations in development and the impact that culture and the environment have on shaping our lives. Culture is the totality of our shared language, knowledge, material objects, and behaviour. It includes ideas about what is right and wrong, what to strive for, what to eat, how to speak, what is valued, as well as what kinds of emotions are called for in certain situations. Culture teaches us how to live in a society and allows us to advance, because each new generation can benefit from the solutions found and passed down from previous generations. Culture is learned from parents, schools, churches, media, friends, and others throughout a lifetime. The kinds of traditions and values that evolve in a particular culture serve to help members function in their own society and to value their own society. We tend to believe that our own culture’s practices and expectations are the right ones. This belief that our own culture is superior is called ethnocentrism and is a by-product of growing up in a culture. It becomes a roadblock, however, when it inhibits understanding of cultural practices from other societies. Cultural relativity is an appreciation for cultural differences and the understanding that cultural practices are best understood from the standpoint of that particular culture.

Culture is an extremely important context for human development and understanding development requires being able to identify which features of development are culturally based. This understanding is somewhat new and still being explored. Much of what developmental theorists have described in the past has been culturally bound and difficult to apply to various cultural contexts. The reader should keep this in mind and realize that there is still much that is unknown when comparing development across cultures.

Lifespan vs. life expectancy: At this point you may be wondering what the difference between lifespan and life expectancy is, according to developmentalists. Lifespan, or longevity, refers to the length of time a species can exist under the most optimal conditions. For instance, the grey wolf can live up to twenty years in captivity, the bald eagle up to fifty years, and the Galapagos tortoise over one hundred and fifty years (Smithsonian National Zoo, 2016). The longest recorded lifespan for a human was Jean Calment who died in 1994 at the age of 122 years, 5 months, and 14 days (Guinness World Records, 2016). Life expectancy is the predicted number of years a person born in a particular time period can reasonably expect to live (Vogt and Johnson, 2016).