157 Neurocognitive Disorders

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

The greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is age, but there are genetic and environmental factors that can also contribute. Some forms of Alzheimer’s disease are hereditary, and with the early-onset type several rare genes have been identified that directly cause the disease. People who inherit these genes tend to develop symptoms in their thirties, forties, and fifties. Five percent of those identified with Alzheimer’s disease are younger than age sixty-five. When Alzheimer’s disease is caused by deterministic genes, it is called familial Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). Traumatic brain injury is also a risk factor, as well as obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes (Carlson, 2011).

According to Erber and Szuchman (2015) the problems that occur with Alzheimer’s disease are due to the “death of neurons, the breakdown of connections between them, and the extensive formation of plaques and tau, which interfere with neuron functioning and neuron survival” (p. 50). Plaques are abnormal formations of protein pieces called beta-amyloid. Beta-amyloid comes from a larger protein found in the fatty membrane surrounding nerve cells. Because beta-amyloid is sticky, it builds up into plaques (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). These plaques appear to block cell communication and may also trigger an inflammatory response in the immune system, which leads to further neuronal death.

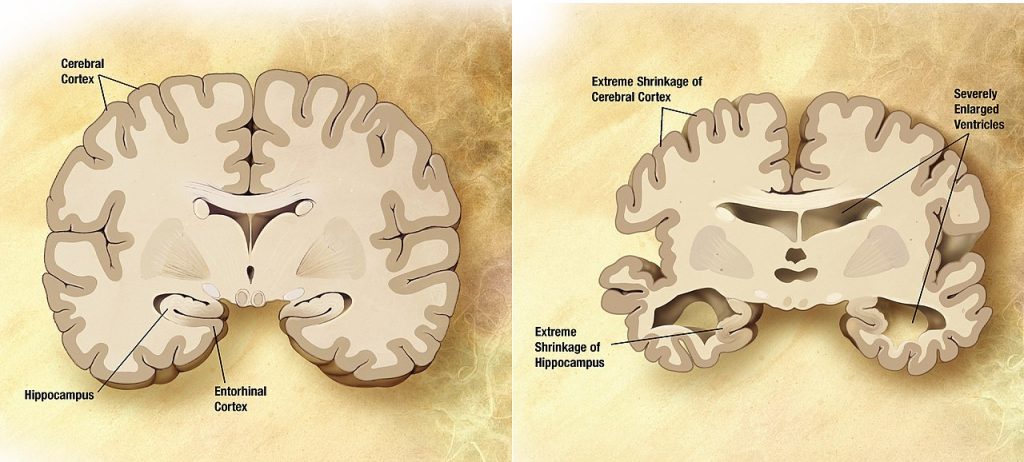

Tau is an important protein that helps maintain the brain’s transport system. When tau malfunctions, it changes into twisted strands called tangles that disrupt the transport system. Consequently, nutrients and other supplies cannot move through the cells and they eventually die. The death of neurons leads to the brain shrinking and affecting all aspects of brain functioning. For example, the hippocampus is involved in learning and memory, and the brain cells in this region are often the first to be damaged. This is why memory loss is often one of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Figures 9.29 and 9.30 illustrate the difference between an Alzheimer’s brain and a healthy brain.

Vascular neurocognitive disorder is the second most common neurocognitive disorder affecting 0.2 percent of the sixty-five to seventy age group and 16 percent of individuals eighty and older (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Vascular neurocognitive disorder is associated with a blockage of cerebral blood vessels that affects one part of the brain rather than a general loss of brain cells seen with Alzheimer’s disease. Personality is not as affected in vascular neurocognitive disorder, and more men are diagnosed than women (Erber and Szuchman, 2015). It also comes on more abruptly than Alzheimer’s disease and has a shorter course before death. Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, or a history of strokes.

Neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies: According to the National Institute on Aging (2015a), Lewy bodies are microscopic protein deposits found in neurons seen postmortem. They affect chemicals in the brain that can lead to difficulties in thinking, movement, behaviour and mood. Neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies is the third most common form and affects more than 1 million Americans. It typically begins at age fifty or older, and appears to affect slightly more men than women. The disease lasts approximately five to seven years from the time of diagnosis to death, but can range from two to twenty years depending on the individual’s age, health, and severity of symptoms. Lewy bodies can occur in both the cortex and brain stem, which result in cognitive as well as motor symptoms (Erber and Szuchman, 2015). The movement symptoms are similar to those with Parkinson’s disease and include tremors and muscle rigidity. However, the motor disturbances occur at the same time as the cognitive symptoms, unlike with Parkinson’s disease when the cognitive symptoms occur well after the motor symptoms. Individuals diagnosed with neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies also experience sleep disturbances and recurrent visual hallucinations, and are at risk for falling.

Media Attributions

- Figure 9 28 © Leveled eggs is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9 29 © Garrondo is licensed under a Public Domain license