93 Eating Disorders

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Dinesh Ramoo

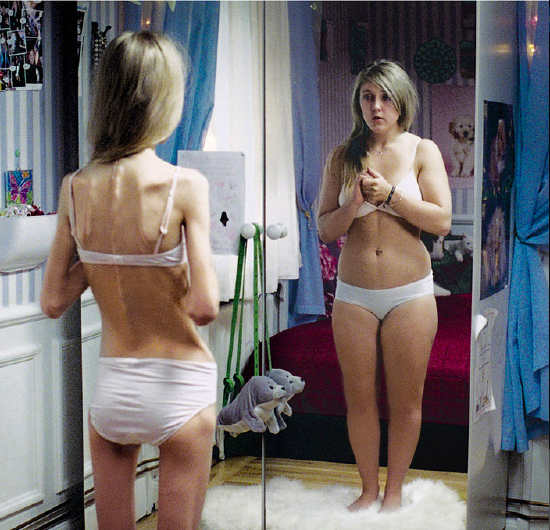

Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). Eating disorders affect both genders, although rates among women are 2.5 times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia or an extreme concern with becoming more muscular. The prevalence of eating disorders in the United States is similar among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians, with the exception that anorexia nervosa is more common among non-Hispanic whites (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, and Kessler, 2007; Wade, Keski-Rahkonen, and Hudson, 2011).

Risk Factors for Eating Disorders

Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of eating disorders and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioural, psychological, and social factors (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women.

The main criteria for the most common eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder) are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and listed in Table 6.1.

| Anorexia nervosa |

|

| Bulimia nervosa |

|

| Binge-eating disorder |

|

Health consequences of eating disorders: For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increases the risk for heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales, and Nielsen, 2011). Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binge and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestive system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge-eating disorder results in health risks similar to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Eating disorder treatment: To treat eating disorders, adequate nutrition and stopping inappropriate behaviours, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counselling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding the child. To eliminate binge-eating and purging behaviours, cognitive behavioural therapy assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

Media Attributions

- Figure 6.10: The Maudsley Family-Based treatment. © Jason Goodman is licensed under a Public Domain license