1.1 Approximating Areas

Learning Objectives

-

Use sigma (summation) notation to calculate sums and powers of integers.

-

Use the sum of rectangular areas to approximate the area under a curve.

-

Use Riemann sums to approximate area.

Archimedes was fascinated with calculating the areas of various shapes—in other words, the amount of space enclosed by the shape. He used a process that has come to be known as the method of exhaustion, which used smaller and smaller shapes, the areas of which could be calculated exactly, to fill an irregular region and thereby obtain closer and closer approximations to the total area. In this process, an area bounded by curves is filled with rectangles, triangles, and shapes with exact area formulas. These areas are then summed to approximate the area of the curved region.

In this section, we develop techniques to approximate the area between a curve, defined by a function ![]() and the

and the ![]() -axis on a closed interval

-axis on a closed interval ![]() Like Archimedes, we first approximate the area under the curve using shapes of known area (namely, rectangles). By using smaller and smaller rectangles, we get closer and closer approximations to the area. Taking a limit allows us to calculate the exact area under the curve.

Like Archimedes, we first approximate the area under the curve using shapes of known area (namely, rectangles). By using smaller and smaller rectangles, we get closer and closer approximations to the area. Taking a limit allows us to calculate the exact area under the curve.

Let’s start by introducing some notation to make the calculations easier. We then consider the case when ![]() is continuous and nonnegative. Later in the chapter, we relax some of these restrictions and develop techniques that apply in more general cases.

is continuous and nonnegative. Later in the chapter, we relax some of these restrictions and develop techniques that apply in more general cases.

Sigma (Summation) Notation

As mentioned, we will use shapes of known area to approximate the area of an irregular region bounded by curves. This process often requires adding up long strings of numbers. To make it easier to write down these lengthy sums, we look at some new notation here, called sigma notation (also known as summation notation). The Greek capital letter ![]() sigma, is used to express long sums of values in a compact form. For example, if we want to add all the integers from 1 to 20 without sigma notation, we have to write

sigma, is used to express long sums of values in a compact form. For example, if we want to add all the integers from 1 to 20 without sigma notation, we have to write

![]()

We could probably skip writing a couple of terms and write

![]()

which is better, but still cumbersome. With sigma notation, we write this sum as ![]() which is much more compact.

which is much more compact.

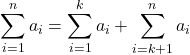

Sigma notation is presented in the form ![]() , where

, where ![]() describes the terms to be added,

describes the terms to be added, ![]() is the index of summation, and

is the index of summation, and ![]() are limits (or bounds) of summation. Each term is evaluated, then we sum all the values, beginning with the value corresponding to

are limits (or bounds) of summation. Each term is evaluated, then we sum all the values, beginning with the value corresponding to ![]() and ending with the one corresponding to

and ending with the one corresponding to ![]() For example, an expression like

For example, an expression like ![]() is interpreted as

is interpreted as ![]() Note that the index is used only to keep track of the terms to be added; it does not factor into the calculation of the sum itself. The index is therefore called a dummy variable. We can use any letter we like for the index. Typically, mathematicians use

Note that the index is used only to keep track of the terms to be added; it does not factor into the calculation of the sum itself. The index is therefore called a dummy variable. We can use any letter we like for the index. Typically, mathematicians use ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() for indices.

for indices.

Let’s try a couple of examples of using sigma notation.

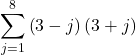

Using Sigma Notation

-

Write in sigma notation and evaluate the sum of terms

for

for

-

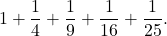

Write the sum in sigma notation:

Solution

-

We have

-

The denominator of each term is a perfect square. Using sigma notation, this sum can be written as

Write in sigma notation and evaluate the sum of terms ![]() for

for ![]()

Answer

The properties associated with the summation process are given below. Note that because the sums arising in the definition of area below a curve and, later, the definite integral typically start from ![]() , we focus on this kind of sums, but all the properties still hold for an arbitrary lower index of summation

, we focus on this kind of sums, but all the properties still hold for an arbitrary lower index of summation ![]() .

.

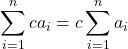

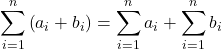

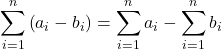

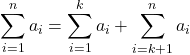

Properties of Sigma Notation

Let ![]() and

and ![]() represent two sequences of terms and let

represent two sequences of terms and let ![]() be a constant. The following properties hold for all positive integers

be a constant. The following properties hold for all positive integers ![]() and for integers

and for integers ![]() , with

, with ![]()

Proof

We prove properties 2 and 3 here, and leave proving the other properties to the Exercises.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}\ds 2.\ \ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}c{a}_{i}\hfill &\ds =c{a}_{1}+c{a}_{2}+c{a}_{3}+\ldots+c{a}_{n}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =c\left({a}_{1}+{a}_{2}+{a}_{3}+\ldots+{a}_{n}\right)\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =c\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{a}_{i}.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-3c97913933367931ef0d689454ecf860_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}\ds3.\ \ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}\left({a}_{i}+{b}_{i}\right)\hfill &\ds =\left({a}_{1}+{b}_{1}\right)+\left({a}_{2}+{b}_{2}\right)+\left({a}_{3}+{b}_{3}\right)+\ldots+\left({a}_{n}+{b}_{n}\right)\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\left({a}_{1}+{a}_{2}+{a}_{3}+\ldots+{a}_{n}\right)+\left({b}_{1}+{b}_{2}+{b}_{3}+\ldots+{b}_{n}\right)\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{a}_{i}+\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{b}_{i}.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-fc4ecd1e207f2f5cdb1dd84eed4b7569_l3.png)

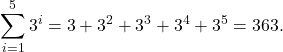

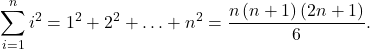

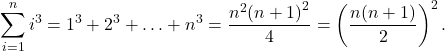

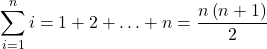

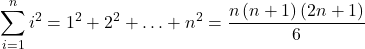

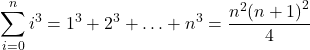

The following formulas for sums of powers of integers simplify the summation process further, and we use them in the next set of examples.

Sums of Powers of Integers

-

The sum of the first

integers is given by

integers is given by

![]()

-

The sum of the squares of the first

integers is given by

integers is given by

-

The sum of the cubes of the first

integers is given by

integers is given by

Evaluation Using Sigma Notation

Write the following sums using sigma notation and then evaluate them.

-

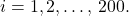

The sum of the terms

for

for

-

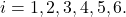

The sum of the terms

for

for

Solution

-

We expand

and then use properties of sigma notation along with the summation formulas to obtain

and then use properties of sigma notation along with the summation formulas to obtain

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}{\left(i-3\right)}^{2}\hfill &\ds =\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}\left({i}^{2}-6i+9\right)\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}{i}^{2}-\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}6i+\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}9 \quad \text{(properties 3 and 4)}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}{i}^{2}-6\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}i+\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{200}9\quad \text{(property 2)} \hfill\\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\frac{200\left(200+1\right)\left(400+1\right)}{6}-6\left[\ds\frac{200\left(200+1\right)}{2}\right]+9\left(200\right)\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =2,686,700-120,600+1800\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =2,567,900\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-93b804a2389e729b2c086797d57d7620_l3.png)

-

We use sigma notation property 4 and the formulas for the sum of squared terms and the sum of cubed terms to obtain

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{6}\left({i}^{3}-{i}^{2}\right)\hfill &\ds =\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{6}{i}^{3}-\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{6}{i}^{2}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\frac{{6}^{2}{\left(6+1\right)}^{2}}{4}-\ds\frac{6\left(6+1\right)\left(2\left(6\right)+1\right)}{6}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\frac{1764}{4}-\ds\frac{546}{6}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =350\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-ac6dc45b6c720b67db816a22fb48bf37_l3.png)

Find the sum of the values of ![]() for

for ![]()

Answer

15,550

Hint

Use the properties of sigma notation to solve the problem.

Finding the Sum of the Function Values

Find the sum of the values of ![]() over the integers

over the integers ![]()

Solution

Using the formula, we have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}\ds\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{10}{i}^{3}\hfill &\ds =\ds\frac{{\left(10\right)}^{2}{\left(10+1\right)}^{2}}{4}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\ds\frac{100\left(121\right)}{4}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =3025.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-6af6c7855da60f697d34a6b461600a9a_l3.png)

Let ![]() . Evaluate the sum

. Evaluate the sum

Answer

440

Hint

Use the rules of sums and formulas for the sum of integers.

Approximating Area

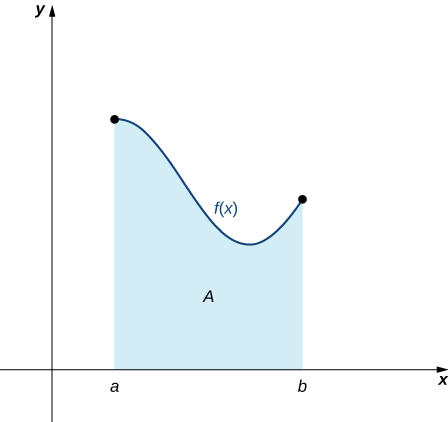

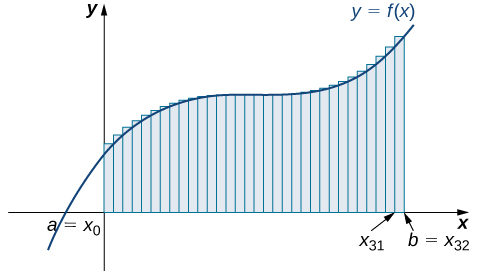

Now that we have the necessary notation, we return to the problem at hand: approximating the area under a curve. Let ![]() be a continuous, nonnegative function defined on the closed interval

be a continuous, nonnegative function defined on the closed interval ![]() We want to approximate the area

We want to approximate the area ![]() of the region under the curve

of the region under the curve ![]() , above the

, above the ![]() -axis, and between the lines

-axis, and between the lines ![]() and

and ![]() , as shown on the figure below.

, as shown on the figure below.

at top, the

at top, the  -axis at bottom, the line

-axis at bottom, the line  at left, and the line

at left, and the line  at right.

at right.To approximate the area under the curve, we use a geometric approach. We divide the region into many small shapes, approximate each of them with a rectangle that has a known area formula, and then sum the areas of rectangles to obtain a reasonable estimate of the area of the region. We begin by dividing the interval ![]() into subintervals. This step is used not only in areas, but also in definite integrals and their applications, so we formally define the relevant terminology.

into subintervals. This step is used not only in areas, but also in definite integrals and their applications, so we formally define the relevant terminology.

Definition

Consider an interval ![]() . A set of points

. A set of points ![]() with

with ![]() which divides the interval

which divides the interval ![]() into subintervals

into subintervals ![]() is called a partition of

is called a partition of ![]() If all the subintervals have the same width, the set of points forms a regular partition of the interval

If all the subintervals have the same width, the set of points forms a regular partition of the interval ![]() For the regular partition, the width of each subinterval is denoted by

For the regular partition, the width of each subinterval is denoted by ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() , and then

, and then ![]() for

for ![]()

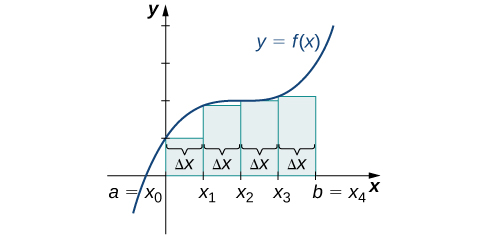

We use the regular partition as the basis of a method for estimating the area under the curve. The method has two variations: the left-endpoint approximation and the right-endpoint approximation, and we examine both of them below.

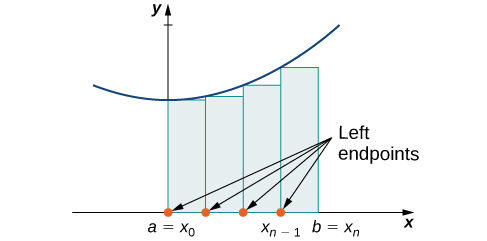

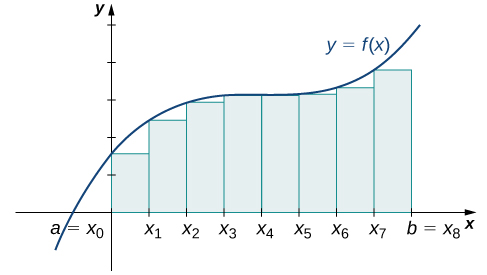

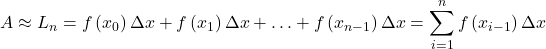

Left-Endpoint Approximation

On each subinterval ![]()

![]() construct a rectangle with a width of

construct a rectangle with a width of ![]() and a height of

and a height of ![]() the function value at the left endpoint of the subinterval, which ensures that the left upper corner of the rectangle belongs to the curve

the function value at the left endpoint of the subinterval, which ensures that the left upper corner of the rectangle belongs to the curve ![]() (see Figure 2 below). This rectangle approximates the region below the graph of

(see Figure 2 below). This rectangle approximates the region below the graph of ![]() over the subinterval

over the subinterval ![]() and its area is

and its area is ![]() Adding the areas of all these rectangles, we get an approximate value for

Adding the areas of all these rectangles, we get an approximate value for ![]() . We use

. We use ![]() to denote the left-endpoint approximation of

to denote the left-endpoint approximation of ![]() using

using ![]() subintervals.

subintervals.

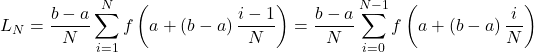

![]()

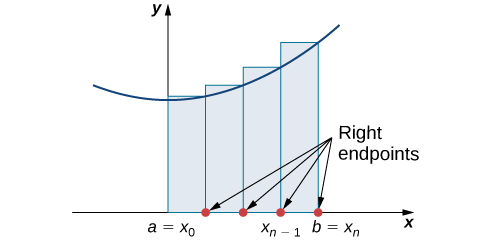

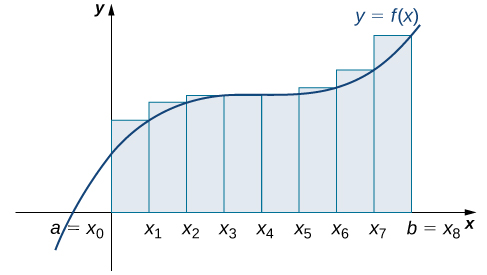

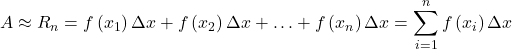

The right-endpoint approximation is very similar to the left-endpoint approximation but, as the name suggests, the heights of the rectangles are determined by the function values at the right endpoint of each subinterval.

Right-Endpoint Approximation

Construct a rectangle on each subinterval ![]()

![]() with the height of

with the height of ![]() , the function value at the right endpoint of the subinterval, which ensures that the right upper corner of the rectangle belongs to the curve

, the function value at the right endpoint of the subinterval, which ensures that the right upper corner of the rectangle belongs to the curve ![]() (see Figure 3 below). Then, the area of each rectangle is

(see Figure 3 below). Then, the area of each rectangle is ![]() and the approximation for

and the approximation for ![]() is given by

is given by

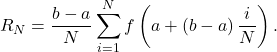

![]()

The notation ![]() indicates this is a right-endpoint approximation for

indicates this is a right-endpoint approximation for ![]() .

.

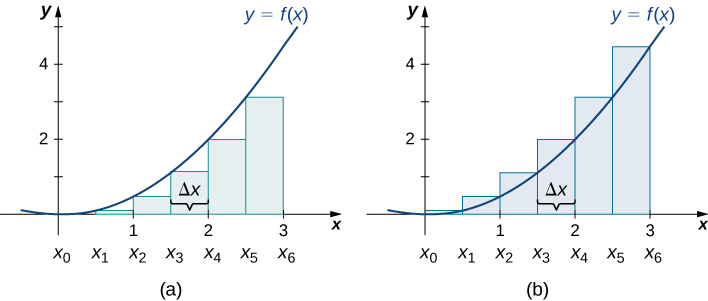

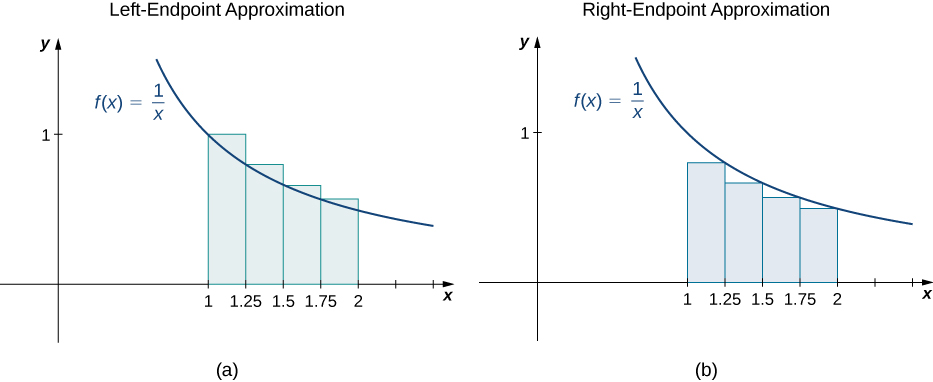

In Figure 4, the area of the region below the graph of the function ![]() over the interval

over the interval ![]() is approximated using left- and right-endpoint approximations with six rectangles.

is approximated using left- and right-endpoint approximations with six rectangles.

In this case, ![]() and the subintervals are

and the subintervals are ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() that is,

that is, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . Using the left- and right-approximation formulas for

. Using the left- and right-approximation formulas for ![]() and

and ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{ll} A&\approx {L}_{6}\ds =\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{6}f\left({x}_{i-1}\right)\Delta x\hfill\\[5mm] \ds&=f\left({x}_{0}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{1}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{2}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{3}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{4}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{5}\right)\Delta x\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =f\left(0\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(0.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(1\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(1.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(2\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(2.5\right)\cdot0.5\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =0\cdot0.5+0.125\cdot0.5+0.5\cdot0.5+1.125\cdot0.5+2\cdot0.5+3.125\cdot0.5\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =0+0.0625+0.25+0.5625+1+1.5625\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =3.4375.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-20215a82b2a12e1202c49454817354eb_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{ll} A&\approx {R}_{6}\ds =\ds\sum\limits_{i=1}^{6}f\left({x}_{i}\right)\Delta x\hfill\\[5mm] \ds &=f\left({x}_{1}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{2}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{3}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{4}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{5}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{6}\right)\Delta x\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =f\left(0.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(1\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(1.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(2\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(2.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(3\right)\cdot0.5\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =0.125\cdot0.5+0.5\cdot0.5+1.125\cdot0.5+2\cdot0.5+3.125\cdot0.5+4.5\cdot0.5\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =0.0625+0.25+0.5625+1+1.5625+2.25\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =5.6875.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-8c6004b18e711b8bc264041e53a955e6_l3.png)

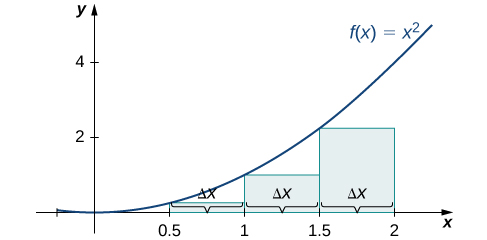

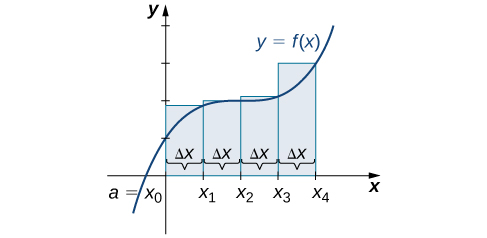

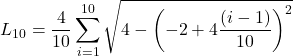

Approximating the Area Under a Curve

Use both left- and right-endpoint approximations to approximate the area under the graph of ![]() over the interval

over the interval ![]() using

using ![]()

Solution

First, divide the interval ![]() into

into ![]() equal subintervals. Using

equal subintervals. Using ![]() This is the width of each rectangle. The intervals

This is the width of each rectangle. The intervals ![]() are shown in Figure 5. Using the left-endpoint approximation, the heights are

are shown in Figure 5. Using the left-endpoint approximation, the heights are ![]() Then,

Then,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{L}_{4}\hfill &\ds =f\left({x}_{0}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{1}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{2}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{3}\right)\Delta x\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =0\cdot0.5+0.25\cdot0.5+1\cdot0.5+2.25\cdot0.5\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =1.75.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-021d1509e56dc3689fc79ae599fb162f_l3.png)

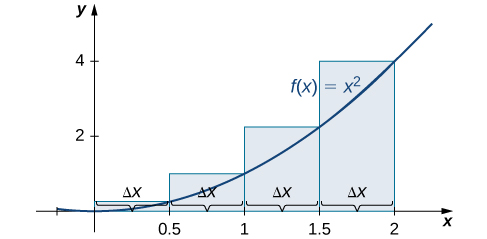

from 0 to 2.

from 0 to 2.The right-endpoint approximation is shown in the Figure 6. The intervals are the same, ![]() but now we use the right endpoints to calculate the heights of the rectangles. We have

but now we use the right endpoints to calculate the heights of the rectangles. We have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{R}_{4}\hfill &\ds =f\left({x}_{1}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{2}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{3}\right)\Delta x+f\left({x}_{4}\right)\Delta x\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =0.25\left(0.5\right)+1\left(0.5\right)+2.25\left(0.5\right)+4\left(0.5\right)\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =3.75.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-015eb4dac0466444e2cfd93d50b13dc8_l3.png)

from 0 to 2.

from 0 to 2.According to our calculations, the left-endpoint approximation is 1.75 and the right-endpoint approximation is 3.75.

Sketch left- and right-endpoint approximations for ![]() on

on ![]() using

using ![]() Approximate the area using both methods.

Approximate the area using both methods.

Answer

The left-endpoint approximation is 0.7595. The right-endpoint approximation is 0.6345. See the figure below.

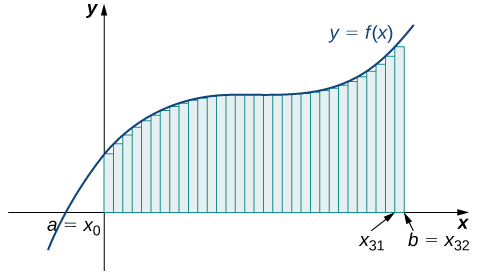

Looking at the graphs above, we can see that when we use a small number of intervals, neither the left- nor the right-endpoint approximation is a particularly accurate estimate of the area under the curve. However, it seems logical that if we increase the number of points in our partition, our estimate of ![]() will improve. We will have more rectangles, but each rectangle will be thinner, so we will be able to fit the rectangles to the curve more precisely.

will improve. We will have more rectangles, but each rectangle will be thinner, so we will be able to fit the rectangles to the curve more precisely.

We demonstrate the improved approximation obtained through smaller intervals with an example. Consider the region under the curve ![]() over the interval

over the interval ![]() . We first explore the left-endpoint approximations with 4 rectangles, then 8 rectangles, and finally 32 rectangles. Then, we explore the right-endpoint approximations, using the same sets of intervals.

. We first explore the left-endpoint approximations with 4 rectangles, then 8 rectangles, and finally 32 rectangles. Then, we explore the right-endpoint approximations, using the same sets of intervals.

![]()

Figure 8 shows the left-endpoint approximation with 8 rectangles. Comparing to Figure 7, we can see less white space under the curve, and since the white space is a part of the region that is not included in the approximating rectangles, we get a better approximation with 8 rectangles. The area of the rectangles is

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{L}_{8}\hfill &\ds =f\left(0\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(0.25\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(0.5\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(0.75\right)\cdot0.25\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds \phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}+f\left(1\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(1.25\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(1.5\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(1.75\right)\cdot0.25\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =7.75.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-27d498550056c187169d1121f133c4c7_l3.png)

The graph in Figure 9 shows the same function with 32 rectangles inscribed under the curve. There appears to be little white space left. The area occupied by the rectangles is

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{L}_{32}\hfill &\ds =f\left(0\right)\cdot0.0625+f\left(0.0625\right)\cdot0.0625+f\left(0.125\right)\cdot0.0625+\ldots+f\left(1.9375\right)\cdot0.0625\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =7.9375.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-3b0fa9e5de7680192f263f6cb5d74d23_l3.png)

We can carry out a similar process for the right-endpoint approximation method. A right-endpoint approximation of the same curve, using four rectangles (as shown in Figure 10), yields an area

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{R}_{4}\hfill &\ds =f\left(0.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(1\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(1.5\right)\cdot0.5+f\left(2\right)\cdot0.5\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =8.5.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-7d6869176b52e1598c0ddceef4dfee55_l3.png)

Dividing the region over the interval ![]() into eight rectangles results in

into eight rectangles results in ![]() The graph is shown in Figure 11. The area is

The graph is shown in Figure 11. The area is

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{R}_{8}\hfill &\ds =f\left(0.25\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(0.5\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(0.75\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(1\right)\cdot0.25\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds \phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}+f\left(1.25\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(1.5\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(1.75\right)\cdot0.25+f\left(2\right)\cdot0.25\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =8.25.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-1552485efaba7ef2f678b4b39c0fca83_l3.png)

Last, the right-endpoint approximation with ![]() is close to the actual area (see Figure 12 below). The area is approximately

is close to the actual area (see Figure 12 below). The area is approximately

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{cc}{R}_{32}\hfill &\ds =f\left(0.0625\right)\cdot0.0625+f\left(0.125\right)\cdot0.0625+f\left(0.1875\right)\cdot0.0625+\ldots+f\left(2\right)\cdot0.0625\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =8.0625.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-a5ebc7a78a83cb10f26f78c53dadb48b_l3.png)

Based on these figures and calculations, it appears we are on the right track; the rectangles appear to approximate the area under the curve better as ![]() gets larger. Furthermore, as

gets larger. Furthermore, as ![]() increases, both the left-endpoint and right-endpoint approximations appear to approach an area of 8 square units. The table below shows a numerical comparison of the left- and right-endpoint methods. The idea that the approximations of the area under the curve get better and better as

increases, both the left-endpoint and right-endpoint approximations appear to approach an area of 8 square units. The table below shows a numerical comparison of the left- and right-endpoint methods. The idea that the approximations of the area under the curve get better and better as ![]() gets larger and larger is very important, and we now explore this idea in more detail.

gets larger and larger is very important, and we now explore this idea in more detail.

| Values of |

Approximate Area |

Approximate Area |

|---|---|---|

| 7.5 | 8.5 | |

| 7.75 | 8.25 | |

| 7.94 | 8.06 |

Forming Riemann Sums

So far, to approximate the area under a curve, we have been using rectangles with the heights determined by evaluating the function at either the left or the right endpoint of the subinterval ![]() . However, we could evaluate the function at any point

. However, we could evaluate the function at any point ![]() in

in ![]() , and use

, and use ![]() as the height of the approximating rectangle. This would result in an estimate

as the height of the approximating rectangle. This would result in an estimate ![]() .

.

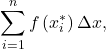

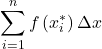

The arising sum is called a Riemann sum, named after the 19th-century mathematician Bernhard Riemann, who developed the idea.

Riemann Sum

Let the function ![]() be defined on a closed interval

be defined on a closed interval ![]() and let

and let ![]() be a regular partition of

be a regular partition of ![]() with the subinterval width

with the subinterval width ![]() . For each

. For each ![]() , let

, let ![]() be an arbitrary point in

be an arbitrary point in ![]() . The numbers

. The numbers ![]() are called the sample points. Then the Riemann sum for

are called the sample points. Then the Riemann sum for ![]() that corresponds to the partition

that corresponds to the partition ![]() and the set of sample points

and the set of sample points ![]() is defined as

is defined as

Recall that with the left- and right-endpoint approximations, the estimates seem to improve as ![]() gets larger. The same is true for the Riemann sums, that is, Riemann sums give better approximations for the area under the curve for larger values of

gets larger. The same is true for the Riemann sums, that is, Riemann sums give better approximations for the area under the curve for larger values of ![]() . We are now ready to define the area under a curve in terms of Riemann sums.

. We are now ready to define the area under a curve in terms of Riemann sums.

Definition

Let ![]() be a continuous, nonnegative function on an interval

be a continuous, nonnegative function on an interval ![]() and let

and let ![]() be a Riemann sum for

be a Riemann sum for ![]() Then, the area under the curve

Then, the area under the curve ![]() over

over ![]() is given by

is given by

Some subtleties here are worth discussing. First, note the above limit is a bit different from the limit of a function ![]() as

as ![]() , because

, because ![]() can only take positive integer values. However, the computational techniques we used to compute limits of functions can also be used to this kind of limits.

can only take positive integer values. However, the computational techniques we used to compute limits of functions can also be used to this kind of limits.

Second, one might wonder if the limit could be different for different choices of sample points ![]() Fortunately, this does not happen. Although the proof is beyond the scope of this text, it can be shown that if

Fortunately, this does not happen. Although the proof is beyond the scope of this text, it can be shown that if ![]() is continuous on the closed interval

is continuous on the closed interval ![]() then

then ![]() exists, and it does not depend on the choice of

exists, and it does not depend on the choice of ![]()

We now discuss some specific choices for ![]() Although any choice for

Although any choice for ![]() gives us an estimate of the area under the curve, we don’t necessarily know whether that estimate is bigger (estimate from above, or overestimate) or smaller (estimate from below, or underestimate) than the actual value of the area. However, we can always select the sample points

gives us an estimate of the area under the curve, we don’t necessarily know whether that estimate is bigger (estimate from above, or overestimate) or smaller (estimate from below, or underestimate) than the actual value of the area. However, we can always select the sample points ![]() to guarantee an estimate from above or from below.

to guarantee an estimate from above or from below.

To ensure an overestimate, it is enough to choose ![]() such that

such that ![]() for all

for all ![]() (

(![]() ) . In other words, for each

) . In other words, for each ![]() , we take

, we take ![]() to be the point where

to be the point where ![]() attains its global maximum on the interval

attains its global maximum on the interval ![]() (which exists since

(which exists since ![]() is continuous). In this case, the Riemann sum

is continuous). In this case, the Riemann sum ![]() is called an upper sum. Similarly, if we want an underestimate, for each

is called an upper sum. Similarly, if we want an underestimate, for each ![]() , we can choose

, we can choose ![]() to be the point where

to be the point where ![]() attains its global minimum on the interval

attains its global minimum on the interval ![]() . The associated Riemann sum is called a lower sum. Note that if

. The associated Riemann sum is called a lower sum. Note that if ![]() is either increasing or decreasing throughout the interval

is either increasing or decreasing throughout the interval ![]() then the maximum and minimum values of the function occur at the endpoints of the subintervals, so the upper and lower sums are just the same as the left- and right-endpoint approximations.

then the maximum and minimum values of the function occur at the endpoints of the subintervals, so the upper and lower sums are just the same as the left- and right-endpoint approximations.

Finding Lower and Upper Sums

Find the lower sum for ![]() over

over ![]() corresponding to

corresponding to ![]() subintervals.

subintervals.

Solution

We have that ![]() and the intervals are

and the intervals are ![]() Because the function is decreasing over the interval

Because the function is decreasing over the interval ![]() the lower sum is obtained by using the right endpoints of the subintervals as the sample points, that is, it is equal to the right-endpoint approximation.

the lower sum is obtained by using the right endpoints of the subintervals as the sample points, that is, it is equal to the right-endpoint approximation.

![The graph of f(x) = 10 − x^2 from 0 to 2. It is set up for a right-end approximation of the area bounded by the curve and the x axis on [1, 2], labeled a=x0 to x4. It shows a lower sum.](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/sites/27/2022/08/CNX_Calc_Figure_05_01_014-5.jpg)

.

.![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{ll}R_4&\ds=\ds\sum\limits_{k=1}^{4}\left(10-{x_i}^{2}\right)\cdot0.25\\[5mm] &=0.25\left[10-{\left(1.25\right)}^{2}+10-{\left(1.5\right)}^{2}+10-{\left(1.75\right)}^{2}+10-{\left(2\right)}^{2}\right]\\[5mm] &\ds =0.25\left[8.4375+7.75+6.9375+6\right]\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =7.28.\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-c299bd7e1e7700715e534a06fceb237d_l3.png)

Hence, the lower sum is 7.28.

Answer

The upper sum is 8.0313.

![A graph of the function f(x) = 10 − x^2 from 0 to 2. It is set up for a right endpoint approximation over the area [1,2], which is labeled a=x0 to x4. It is an upper sum.](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/sites/27/2022/08/CNX_Calc_Figure_05_01_015-5.jpg)

Hint

![]() is decreasing on

is decreasing on ![]() so the maximum function values occur at the left endpoints of the subintervals.

so the maximum function values occur at the left endpoints of the subintervals.

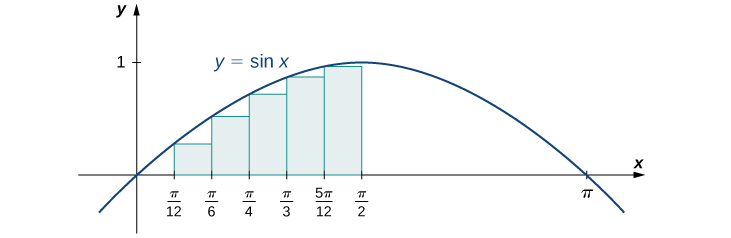

Finding Lower and Upper Sums

Find the lower sum for ![]() over

over ![]() corresponding to

corresponding to ![]() subintervals.

subintervals.

Solution

We have that ![]() , and the intervals are

, and the intervals are ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]() Since

Since ![]() is increasing on the interval

is increasing on the interval ![]() for each subinterval, the function attains its minimum value at the left endpoint, and so the lower sum coincides with the left-endpoint approximation.

for each subinterval, the function attains its minimum value at the left endpoint, and so the lower sum coincides with the left-endpoint approximation.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{ll}L_4 &\ds =\text{sin}\left(0\right)\cdot\ds\frac{\pi }{12}+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{\pi }{12}\right)\cdot\ds\frac{\pi }{12}+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{\pi }{6}\right)\cdot\ds\frac{\pi }{12}\\[5mm]&+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{\pi }{4}\right)\cdot\ds\frac{\pi }{12}+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{\pi }{3}\right)\cdot\ds\frac{\pi }{12}+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{5\pi }{12}\right)\cdot\ds\frac{\pi }{12}\hfill \\[5mm] &\ds =\frac{\pi }{12}\left[0+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{\pi }{12}\right)+\dfrac12+\dfrac{\sqrt2}2+\dfrac{\sqrt3}2+\text{sin}\left(\ds\frac{5\pi }{12}\right)\right]\hfill \end{array}](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-57bb2b538408636486b0f7662cb3b222_l3.png)

So we obtain that the lower sum is equal to the above expression. Note that, using the trigonometric formula ![]() , we can obtain that

, we can obtain that ![]() , and hence the answer can be simplified as

, and hence the answer can be simplified as

![]() .

.

Find the upper sum for ![]() over

over ![]() corresponding to

corresponding to ![]() subintervals.

subintervals.

Answer

![]()

Hint

Compare the expression for the upper sum to the one for the lower sum, and use the answer to the previous example.

Key Concepts

-

Sigma (summation) notation of the form

is useful for expressing long sums of values in compact form.

is useful for expressing long sums of values in compact form. -

For a continuous function defined over an interval

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \left[a,b\right],](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-9437911b3a28f744116a07eb7824b6a6_l3.png) the process of dividing the interval into

the process of dividing the interval into  equal parts, building a rectangle on each of them with the height determined by the value of the function at the left (respectively, right) endpoint of the subinterval, calculating the areas of these rectangles, and then summing the areas yields a left-endpoint (respectively, right-endpoint) approximation of the area below the graph of

equal parts, building a rectangle on each of them with the height determined by the value of the function at the left (respectively, right) endpoint of the subinterval, calculating the areas of these rectangles, and then summing the areas yields a left-endpoint (respectively, right-endpoint) approximation of the area below the graph of  .

. -

The width of each rectangle is

-

Riemann sums are expressions of the form

and they can be used to estimate the area under the curve

and they can be used to estimate the area under the curve  Left- and right-endpoint approximations are particular cases of Riemann sums.

Left- and right-endpoint approximations are particular cases of Riemann sums. -

Riemann sums allow for much flexibility in choosing the set of points

at which the function is evaluated, often with an eye to obtaining a lower sum or an upper sum.

at which the function is evaluated, often with an eye to obtaining a lower sum or an upper sum.

Key Equations

-

Properties of Sigma Notation

-

Sums and Powers of Integers

-

Left-Endpoint Approximation

-

Right-Endpoint Approximation

Exercises

1. State whether the given sums are equal or unequal.

-

and

and

-

and

and

-

and

and

-

and

and

Answer

a. They are equal; both represent the sum of the first 10 whole numbers.

b. They are equal; both represent the sum of the first 10 whole numbers.

c. They are equal by substituting ![]()

d. They are equal; the first sum factors the terms of the second.

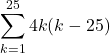

In the following exercises, use the formulas for sums of powers of integers and the 5-th property of sigma notation to compute the sums.

2. ![]()

3. ![]()

Answer

![]()

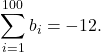

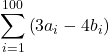

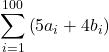

Suppose that  and

and  In the following exercises, compute the sums.

In the following exercises, compute the sums.

4.

5.

Answer

![]()

6.

7.

Answer

![]()

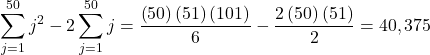

In the following exercises, use summation properties and formulas to rewrite and evaluate the sums.

8.

9.

Answer

10.

11.

Answer

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \ds\sum\limits_{k=1}^{25}\left[4k^2-100k\right]=\ds\frac{4\left(25\right)\left(26\right)\left(51\right)}{6}-50\left(25\right)\left(26\right)=-10,400](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-33c3501a1ab06f97c79caf2644711166_l3.png)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() denote, respectively, the left- and the right-endpoint approximations of the area under

denote, respectively, the left- and the right-endpoint approximations of the area under ![]() over the interval

over the interval ![]() . In the following exercises, compute the indicated left- and right-endpoint approximations of the areas corresponding to the given functions and intervals.

. In the following exercises, compute the indicated left- and right-endpoint approximations of the areas corresponding to the given functions and intervals.

12. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

13. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

Answer

![]()

14. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

15. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

Answer

![]()

16. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

17. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

Answer

![]()

18. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

19. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

Answer

![]()

20. Compute the left and right Riemann sums — ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively — for

, respectively — for ![]() over

over ![]() Compute their average value and compare it with the area under the graph of

Compute their average value and compare it with the area under the graph of ![]() .

.

21. Compute the left and right Riemann sums — ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively — for

, respectively — for ![]() over

over ![]() Compute their average value and compare it with the area under the graph of

Compute their average value and compare it with the area under the graph of ![]() .

.

Answer

![]() The graph of

The graph of ![]() is a triangle with area 9.

is a triangle with area 9.

22. Compute the left and right Riemann sums — ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively — for

, respectively — for ![]() over

over ![]() and compare their values.

and compare their values.

23. Compute the left and right Riemann sums — ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively — for

, respectively — for ![]() over

over ![]() and compare their values.

and compare their values.

Answer

![]() They are equal.

They are equal.

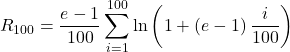

Express the following endpoint sums in sigma notation but do not evaluate them.

24. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

25. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

Answer

26. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

27. ![]() for

for ![]() over

over ![]()

Answer

28. Let ![]() denote the time that it took Tejay van Garteren to ride the

denote the time that it took Tejay van Garteren to ride the ![]() -th stage of the Tour de France in 2014. If there were a total of 21 stages, interpret

-th stage of the Tour de France in 2014. If there were a total of 21 stages, interpret ![]()

29. Let ![]() denote the total rainfall in Portland on the

denote the total rainfall in Portland on the ![]() -th day of the year in 2009. Interpret

-th day of the year in 2009. Interpret ![]()

Answer

The sum represents the cumulative rainfall in January 2009.

30. Let ![]() denote the hours of daylight and

denote the hours of daylight and ![]() denote the increase in the hours of daylight from day

denote the increase in the hours of daylight from day ![]() to day

to day ![]() in Fargo, North Dakota, on the

in Fargo, North Dakota, on the ![]() th day of the year. Interpret

th day of the year. Interpret

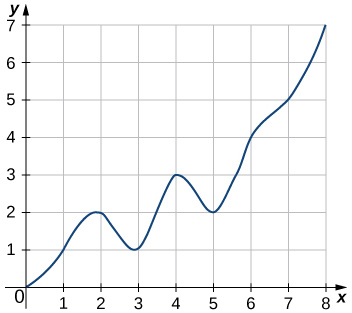

31. To help get in shape, Joe gets a new pair of running shoes. If Joe runs 1 mi each day in week 1 and adds ![]() mi to his daily routine each week, what is the total mileage on Joe’s shoes after 25 weeks?

mi to his daily routine each week, what is the total mileage on Joe’s shoes after 25 weeks?

Answer

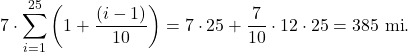

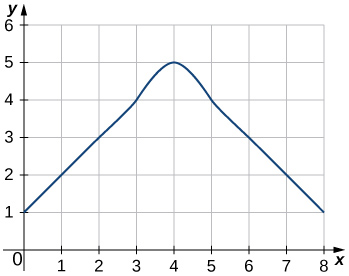

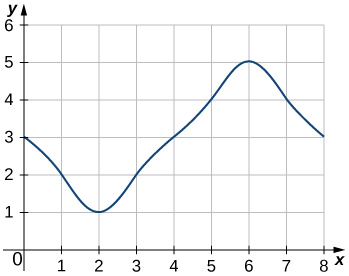

In the following exercises, estimate the areas under the curves by computing the left Riemann sums, ![]() .

.

32.

33.

Answer

![]()

34.

35. Explain why, if ![]() and

and ![]() is increasing on

is increasing on ![]() then the left-endpoint approximation is a lower bound for the area below the graph of

then the left-endpoint approximation is a lower bound for the area below the graph of ![]() on

on ![]()

Solution

If ![]() is a subinterval of

is a subinterval of ![]() , then since

, then since ![]() is increasing, we have that

is increasing, we have that ![]() for

for ![]() This means that the approximating rectangle corresponding to the subinterval

This means that the approximating rectangle corresponding to the subinterval ![]() is completely inside the region below the graph of

is completely inside the region below the graph of ![]() over this subinterval, and hence the area of the rectangle is no bigger than the area of this region. As this is true for each approximating rectangle, when we sum up their areas, we obtain that the left Riemann sum is less than or equal to the area below the graph of

over this subinterval, and hence the area of the rectangle is no bigger than the area of this region. As this is true for each approximating rectangle, when we sum up their areas, we obtain that the left Riemann sum is less than or equal to the area below the graph of ![]() over

over ![]()

36. Explain why, if ![]() and

and ![]() is decreasing on

is decreasing on ![]() then the left-endpoint approximation is an upper bound for the area below the graph of

then the left-endpoint approximation is an upper bound for the area below the graph of ![]() over

over ![]()

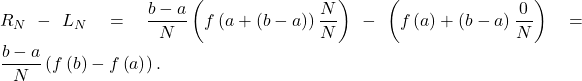

37. Show that, in general, ![]()

Solution

and

and  The left sum has a term corresponding to

The left sum has a term corresponding to ![]() and the right sum has a term corresponding to

and the right sum has a term corresponding to ![]() In

In ![]() any term corresponding to

any term corresponding to ![]() occurs once with a plus sign and once with a minus sign, so each such term cancels and one is left with

occurs once with a plus sign and once with a minus sign, so each such term cancels and one is left with

38. Explain why, if ![]() is increasing on

is increasing on ![]() the error between either

the error between either ![]() or

or ![]() and the area

and the area ![]() below the graph of

below the graph of ![]() is at most

is at most ![]()

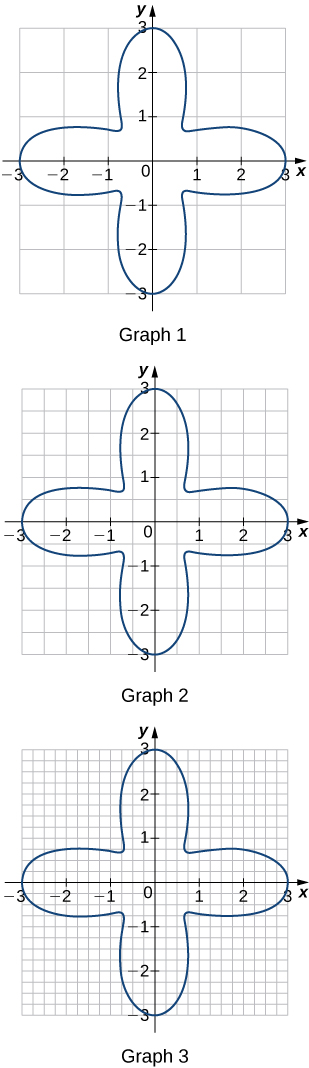

39. For each of the three graphs:

-

Obtain a lower bound

for the area enclosed by the curve by adding the areas of the squares enclosed completely by the curve.

for the area enclosed by the curve by adding the areas of the squares enclosed completely by the curve. -

Obtain an upper bound

for the area by adding to

for the area by adding to  the areas

the areas  of the squares enclosed partially by the curve.

of the squares enclosed partially by the curve.

Answer

Graph 1: a. ![]() b.

b. ![]() Graph 2: a.

Graph 2: a. ![]() b.

b. ![]() Graph 3: a.

Graph 3: a. ![]() b.

b. ![]()

40. In the previous exercise, explain why ![]() gets no smaller while

gets no smaller while ![]() gets no larger as the squares are subdivided into four boxes of equal area.

gets no larger as the squares are subdivided into four boxes of equal area.

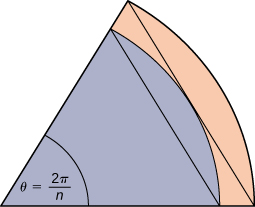

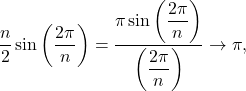

41. A unit circle is made up of ![]() wedges equivalent to the inner wedge in the figure. The base of the inner triangle is 1 unit and its height is

wedges equivalent to the inner wedge in the figure. The base of the inner triangle is 1 unit and its height is ![]() The base of the outer triangle is

The base of the outer triangle is ![]() and the height is

and the height is ![]() Use this information to argue that the area of a unit circle is equal to

Use this information to argue that the area of a unit circle is equal to ![]() .

.

Solution

Let ![]() be the area of the unit circle. The circle encloses

be the area of the unit circle. The circle encloses ![]() congruent triangles each of area

congruent triangles each of area  so

so ![]() Similarly, the circle is contained inside

Similarly, the circle is contained inside ![]() congruent triangles each of area

congruent triangles each of area ![]() and so

and so ![]() As

As ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() , implying that

, implying that  and hence

and hence ![]() We also have that

We also have that ![]() as

as ![]() , which yields

, which yields ![]() Therefore,

Therefore, ![]()

Glossary

- sigma notation

- (also, summation notation) the Greek letter sigma (

) indicates addition of the values; the values of the index above and below the sigma indicate where to begin the summation and where to end it

) indicates addition of the values; the values of the index above and below the sigma indicate where to begin the summation and where to end it

- partition

- a set of points that divides an interval into subintervals

- regular partition

- a partition in which the subintervals all have the same width

- left-endpoint approximation

- an approximation of the area under a curve computed by using the left endpoint of each subinterval to calculate the height of the approximating rectangle

- right-endpoint approximation

- an approximation of the area under a curve using the right endpoint of each subinterval to calculate the height of the approximating rectangle

- riemann sum

- the sum of the form

, where each

, where each  is a sample point in the subinterval

is a sample point in the subinterval ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [x_{i-1},x_i]](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-c0e51ec9f8eb90c1cee0e08b34e26340_l3.png)

- lower sum

- a Riemann sum obtained by using the minimum value of

on each subinterval

on each subinterval

- upper sum

- a Riemann sum obtained by using the maximum value of

on each subinterval

on each subinterval