Indian Residential Schools

For roughly seven generations nearly every Indigenous child in Canada was sent to a residential school. They were taken from their families, tribes and communities, and forced to live in those institutions of assimilation. The results while unintended have been devastating. We witness it first in the loss of Indigenous languages and traditional beliefs. We see it more tragically in the loss of parenting skills, and, ironically, in unacceptably poor education results. We see the despair that results in runaway rates of suicide, family violence, substance abuse, high rates of incarceration, street gang influence, child welfare apprehensions, homelessness, poverty, and family breakdowns. Yet while the government achieved such unintended devastation, it failed in its intended result. Indians never assimilated.

– Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair (Mizanay Gheezhik; Ojibway; first Indigenous judge in Manitoba, superior court judge, adjunct professor, and chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission), speech to the United Nations, 2010.

One of the most infamous consequences of the Indian Act was the promotion of residential schools. Duncan Campbell Scott, Head of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, famously said in 1920 that “the goal of the Indian Residential School is to ‘kill the Indian in the child.’” Sadly, in many cases, this goal was accomplished. Children were not allowed to speak their language and had to give up their cultural practices, beliefs, and any connection to their Indigenous way of life.

Today, Indigenous Peoples are still living with the legacy of residential schools in the form of post-traumatic stress and intergenerational trauma.

The legacy of the residential school system is still with us today, and it is important that all people understand its history and legacy. Only when we understand the true history of Canada and its relationship with Indigenous Peoples can reconciliation begin. We can create a Canada that is inclusive of Indigenous Peoples and where Indigenous Peoples are self-determining in a nation-to-nation relationship.

The Indian Residential School System

The residential school system consisted of 140 schools across the country, funded by the federal government and run by churches. More than 150,000 Indigenous children attended the schools. The Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario, opened in 1830, and took in its first boarding school student in 1831 (Miller et al., 2021, para. 3). The first government-funded residential schools were opened in the 1870s. The last federally funded residential school closed in 1996 in Saskatchewan.

Day schools and residential schools were made mandatory for Indigenous children between the ages of 7 and 15 in 1884. Parents could no longer choose between sending their children to the schools and keeping them at home, and they could be fined or even sent to prison if they tried to keep their children at home.

The government wanted to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into Canadian society, which meant they would have to give up their languages, spiritual beliefs, and cultural practices. Indigenous children were removed from their parents, family, and all cultural influences and traditions. They lived at residential schools for months or years at a time rather than going home every day after class. Many of these children did not see their families for very long periods of time.

Since the intent of the government and churches was to erase Indigenous culture in the children— “kill the Indian in the child” and stop the transmission of culture from one generation to another—many people think the residential schools were a form of cultural genocide.

The Residential School Experience

On the children’s arrival at the residential schools, the staff took away their clothes and cultural belongings. Their hair was cut and they were required to wear Euro-Canadian uniforms. They were forbidden to speak their language, practise their cultural traditions, or spend time with children of the opposite sex, including their brothers and sisters, and were physically punished if they did. They were required to practise Christianity.

Children usually attended school in the morning and the boys worked as farm labourers in the afternoon while the girls did domestic chores and cleaned. They often received only a Grade 5 education, as it was expected that they would be low-paid workers in Canadian society.

The government paid the church a certain amount of money for each student. The more students at the school, the more money the church would receive. The children did not get enough food and lived in buildings that were hot in the summer and cold in the winter. Overcrowding and poor diet meant that diseases spread rapidly, and many students died in the schools.

Disconnection from their families, communities, languages, and cultures led to great suffering for the children. Many also experienced neglect and abuse—physical, psychological, and sexual—at the schools. Some committed suicide. Some died trying to escape. Indigenous children are the only children in Canadian history to be taken from their families and required by law to live in institutions because of their race and culture.

For most Indigenous people, the memories of residential school are negative and life-altering. They remember feeling lonely, hungry, and scared. They remember being told that Indigenous culture is strange and inferior, that Indigenous beliefs and practices are wrong, and that they would never be successful.

The Métis Experience with the Residential School System

The Métis experience with the Indian residential school system was complex because neither the federal nor the provincial governments felt that education was their responsibility–specifically when it came to, ‘who’ would be paying for the education of Métis students. Additionally, if a family was a ‘Road Allowance’ family, they would often be denied access to provincial education because they weren’t paying land taxes which determine the educational tax. Some Métis students attended Residential schools, day schools, and others attended provincial schools. With all that said, the experience for the Métis across the Métis Nation homeland varies and can be diverse from family to family, region to region, and province to province.

Unfortunately, the Métis were not officially included in the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada, which helped to better understand the legacy of the Residential Schools in Canada. As a result, very little research has enabled the Métis Nation to fully understand the scope and legacy of the Indian Residential School and Day schools as it pertains to Métis education.

Learn more about the Métis residential school experience1.

Watch more2 about the Métis experience.

The Continuing Legacy of the Indian Residential School System

Canada’s residential school system had and continues to have serious consequences for Indigenous Peoples. It is important to understand this history so it is not repeated and to work toward righting the wrongs of the past so Indigenous and non-Indigenous people can move forward in a spirit of nation-to-nation relationship based on respect, transparency, and accountability.

The discovery of the bodies of 215 children in an unmarked mass grave at a residential school outside of Kamloops, BC, has shocked many Canadians and brought the trauma and suffering of the survivors and the deceased to widespread recognition. Many are calling upon the federal government and church groups to fully investigate residential school sites to reveal the full count and identities of those whose young lives were lost because of the policy of cultural genocide. The former Brandon Indian Residential School site is currently being led by the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation with partners at Simon Fraser University, Brandon University, and the University of Windsor (Finding Indigenous Children: The Brandon Indian Residential School Project, 2021).

Loss of confidence and culture

Many of the people who attended residential schools left with very little education and a belief that it is shameful to be an “Indian.” Many were unable to speak their language, so they could not communicate with their family members and particularly their grandparents, who in many communities would have been important sources of knowledge for them. Many also found it hard to fit into Canadian society. They had a low level of education and faced racism and discrimination when they tried to find work. Unable to fit into community life and not accepted in mainstream society, some felt that they did not belong anywhere.

Psychological Effects

Many people who attended residential schools experienced a variety of psychological effects, including:

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—terror, nightmares, and flashbacks that develop after a terrifying experience

- survivor syndrome—guilt felt by people who have survived a threatening situation that others did not survive

Sadly, the effects of residential schools are not only felt by those who attended residential schools. Intergenerational trauma are the effects of traumatic experiences passed on to the next generations. For example, the children and grandchildren of residential school survivors grow up feeling that something is wrong, but they do not know what because parents and relatives live with the pain and grief of their experiences in silence.

Effects on communities

Traditionally, Indigenous histories, traditions, beliefs, and values were passed from one generation to the next through experiential learning and oral storytelling. With the children away at school, there was no one left to receive this knowledge. Many Indigenous languages that were spoken in Canada are now gone. Many cultural and spiritual practices have been lost.

The loss of culture is a loss for both Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people in Canada. Families suffered from the separation for many years. Because they were removed from their families, many students grew up without the knowledge and skills to raise their own families. It prevented children from learning from their Elders and growing into a role in their community and having a healthy self-esteem and identity.

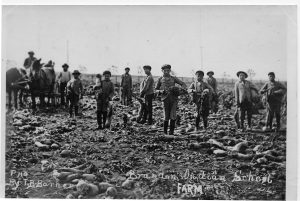

Brandon Residential School

The residential school in Brandon opened in 1895. There was great resistance on the part of the parents of the children being taken to the school. It was clear that the goals of the school were under suspicion from the time it opened:

When heading northward, Semmens [the superintendent] recorded several questions frequently asked by parents, including if the children would return after their studies were completed, was it the government’s plan to destroy their languages and tribal life, whether their children would be enslaved and exploited for money, if the children could freely return home by their own decision or the decision of their parents and if the government would actually keep their promises surrounding the schools. (Slark, 2021, p. B5)

Although the federal government pressed on with compulsory attendance, initially the school recorded sparse attendance. Decades later, the school’s records indicate that children ran away with alarming frequency. Parents complained about their children being fed a poor diet while being housed at the school. Despite these realities, one teacher interviewed for an article in the Winnipeg Free Press expressed hopes that the school’s environment would educate students to the point that they would become “discontented” with their reserve communities (Slark, 2021). Allegations of abuse were not unheard of, but did not appear to be thoroughly investigated. The vacant school was demolished in 2000.

The land that the school and its grounds occupied is now owned by three entities: the research farm, a private campground owner, and Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. The landscape has been flooded repeatedly in the last few decades. To date, there are estimated to be 104 children’s bodies buried in three sites, though there are only records of 78 deceased children (Slark, 2021). Access to the site is limited by the complicated division of ownership. A research partnership of Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, Simon Fraser University, Brandon University, and the University of Windsor has secured Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council funding to aid in identify the children. The complete investigation of residential school remains of children is the subject of #71-76 of the 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

There were many other residential schools throughout Manitoba and Canada. At the time of writing, many are being investigated with ground penetrating radar to begin to account for the children whose bodies remain at the schools, largely in unmarked graves. Along with the TRC, many Indigenous leaders, communities, and families of the children are calling for complete physical investigation of all school sites and the opening of church records. There are also calls for criminal investigation of the children’s deaths in cases where that action is appropriate. There have also been repeated calls for an official apology from the Vatican.

Residential Schools Locations3

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation4

Apologies and Reparations

In the 1990s, groups of residential school survivors sued the Canadian government and the churches that ran the schools. One of the largest class action suits in Canadian history was settled in 2007. It resulted in the establishment of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and payment of $1.9 billion. This settlement made several promises. It gave more funds to the Indigenous Healing Foundation (now closed) for healing programs in communities and offered payments to survivors as reparation. Reparation payments are compensation for past wrongs endured by the victims.

The official apology

On June 11, 2008, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology. You can view a video of the apology 1online. Here is part of the text of the apology:

The treatment of children in Indian Residential Schools is a sad chapter in our history.… Two primary objectives of the Residential Schools system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions, and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives were based on the assumption Indigenous cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. Indeed, some sought, as it was infamously said, “to kill the Indian in the child.” Today, we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country…. To the approximately 80,000 living former students, and all family members and communities, the Government of Canada now recognizes that it was wrong to forcibly remove children from their homes and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that it was wrong to separate children from rich and vibrant cultures and traditions that it created a void in many lives and communities, and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that, in separating children from their families, we undermined the ability of many to adequately parent their own children and sowed the seeds for generations to follow, and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that, far too often, these institutions gave rise to abuse or neglect and were inadequately controlled, and we apologize for failing to protect you. Not only did you suffer these abuses as children, but as you became parents, you were powerless to protect your own children from suffering the same experience, and for this we are sorry.…

Healing

Many Indigenous families and communities have organized formally and informally to heal from residential school legacies, and many survivors are now Elders. The Indian Residential School Survivors Society (IRSSS)6 grew out of a committee of survivors in 1994. It has centres in B.C. cities, including Vancouver. Its many projects include providing crisis counselling, court support, workshops, conferences, information and referrals, and media announcements. The society researches the history and effects of residential schools. The IRSSS also advocates for justice and healing in traditional and non-Indigenous ways.

Media Attributions

‘Brandon Indian School Farm (1913-1915)’ (SJ McKee Archives, Brandon University) is licensed under a Public Domain License.

‘Post Card View of Brandon Indian Residential School (circa 1910)’ (Gordon Goldsborough) is licensed under a Public Domain License.

Notes

- Métis Residential School Experience (https://www.ahf.ca/files/metiseweb.pdf)

- Residential Schools: Métis Experience (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6JGmsfg-aQ)

- Residential Schools Locations (https://nctr.ca/records/view-your-records/archival-map/)

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (https://nctr.ca/education/teaching-resources/residential-school-history/)

- Official Apology (https://youtu.be/-ryC74bbrEE)

- Indian Residential School Survivors Society (https://www.irsss.ca/)