11 Memory

Memory

Rebecca Hiebert

Learning Objectives

After reading this page, you will be able to:

- manage short- and long-term memory;

- avoid cramming before a test;

- use memory strategies.

Why Is This important?

We need to understand how our brain works in order to maximize our ability to memorize important course material. When we implement good memorization strategies, we will be able to retain the information we need to succeed with our classes.

Memory

We go through three basic steps when we remember ideas or images: we encode, store, and retrieve that information. Encoding is how we first perceive information through our senses, such as when we smell a lovely flower or a putrid trash bin. Both make an impression on our minds through our sense of smell and probably our vision. Our brains encode, or label, this content in short-term memory in case we want to think about it again.

If the information is important and we have frequent exposure to it, the brain will store it in our long-term memory in case we need to use it in the future. Later, the brain will allow us to recall or retrieve that image, feeling, or information so we can do something with it. This is what we call remembering.

Exercise

Take a few minutes to list ways you create memories on a daily basis.

- Do you think about how you make memories?

- Do you do anything that helps you keep track of your memories?

Working Memory

Working memory is a type of short-term memory we use when we are actively performing a task. In working memory, you have access to whatever information you have stored in your memory that helps you complete the task you are performing. For instance, when you begin to study an assignment, you need to read the directions, but you must also remember that in class your professor reduced the number of questions you needed to finish. This was an verbal addition to the written assignment. The change to the instructions is what you bring up in working memory when you complete the assignment.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory helps us remember where we set our keys or where we left off on a project the day before. Think about all the aids we employ to help us with short-term memory. You may hang your keys in a particular place each evening so you know exactly where they are supposed to be. You may memorize what a certain corner store looks like so that you know where to turn off to get to your friends house. We help our memory along all the time, which is perfectly fine. In fact, we can modify these everyday examples of memory assistance for the purposes of studying and test taking.

Exercise

Consider this list of items. Look at the list for no more than 30 seconds. Then, cover up the list and use the spaces below to complete an activity.

| baseball | picture frame | tissue | paper clip |

| bread | pair of dice | fingernail polish | spoon |

| marble | leaf | doll | scissors |

| cup | jar of sand | deck of cards | ring |

| blanket | ice | marker | string |

Without looking at the list, write down as many items as you can remember.

Now, look back at your list and make sure that you give yourself credit for any items that you got right. Any items that you misremembered, meaning they were not in the original list, won’t count in your total.

Total items remembered: __________

There is a total of 20 items. If you remembered between five and nine items, then you have a typical short-term memory and you just participated in an experiment to prove it.

Chunking

Considering the vast amount of knowledge available to us, five to nine bits isn’t very much to work with. To combat this limitation, we clump information together, making connections to help us stretch our capacity to remember. Many factors play into how much we can remember and how we do it, including the subject matter, how familiar we are with the ideas, and how interested we are in the topic. It can be a challenge to remember everything we need to for a test; we have to use effective strategies, like those we cover later in this chapter, to get the most out of our memories.

Exercise

Now, let’s revisit the items from the above exercise. Go back to them and see if you can organize them in a way that would give you about five groups of items. See below for an example of how to group them.

Row 1: Items found in a kitchen

Row 2: Items that a child would play with

Row 3: Items of nature

Row 4: Items in a desk drawer/school supplies

Row 5: Items found in a bedroom

| cup | spoon | ice | bread | |

| baseball | marble | pair of dice | doll | deck of cards |

| jar of sand | leaf | |||

| marker | string | scissors | paper clip | |

| ring | picture frame | fingernail polish | tissue | blanket |

Now that you have grouped items into categories, also known as chunking, you can work on remembering the categories and the items that fit into those categories, which will result in remembering more items. Check it out below by covering up the list of items again and writing down what you can remember.

Now, look back at your list and make sure that you give yourself credit for any that you got right. Any items that you misremembered, meaning they were not in the original list, won’t count in your total.

Total items remembered: __________

Did you increase how many items you could remember?

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory is exactly what it sounds like. These are things you recall from the past, such as the smell of your elementary school cafeteria or how to ride a bicycle. Our brain keeps a vast array of information, images, and sensory experiences in long-term memory. Whatever it is we are trying to keep in our memories, whether a beautiful song or a list of chemistry vocabulary terms, must first come into our brains in short-term memory. If we want these fleeting ideas to transfer into long-term memory, we have to do some work, such as causing frequent exposure to the information over time (for example, studying the terms every day for a period of time or memorizing multiplication tables or spelling rules) and some relevant manipulation for the information.

We learn the lyrics of a favourite song by singing and/or playing the song over and over. That alone may not be enough to get that song into the coveted long-term memory area of our brain, but if we have an emotional connection to the song, such as a painful breakup or a life-changing proposal that occurred while we were listening to the song, it may help. Think of ways to make your study session memorable and create connections with the information you need to study. That way, you have a better chance of keeping your study material in your memory so you can access it whenever you need it.

Exercise

Think about your own memories and how you ensure that important information is easy to recall while you answer the following questions:

- What are some ways you convert short-term memories into long-term memories?

- Do your memorization strategies differ for specific courses (for example, how you remember for math or history classes)?

Obstacles to Remembering

If remembering things we need to know for exams or for learning new disciplines were easy, no one would have problems with it, but students face several significant obstacles to remembering, including a persistent lack of sleep and an unrealistic reliance on cramming. Life is busy and stressful for all students, so you have to keep practicing strategies to help you study and remember successfully, but you must also be mindful of obstacles to remembering.

Lack of Sleep

Sleep benefits all of your bodily functions, and your brain needs sleep to dream and rest through the night. You probably can recall times when you had to do something without adequate sleep. When this happens, we say things like “I just can’t wake up” and “I’m walking around half asleep.”

If you can’t focus well because you didn’t get enough sleep, then you likely won’t be able to remember whatever it is you need to recall for any sort of studying or test-taking situation. Most tests and exams in a college setting will require you to recall memorized facts as well as apply and analyze those facts to new case studies or situations. Trying to make these mental connections on too little sleep will take a large mental toll because you will have to concentrate even harder than you would with adequate sleep. Although not an exact comparison, think about when you overtax a computer by opening too many programs simultaneously. Sometimes the programs are sluggish or slow to respond, making it difficult to work efficiently; sometimes the computer shuts down completely and you have to reboot the entire system. Your body is a bit like that on too little sleep.

Conversely, your brain on adequate sleep is amazing, and sleep can actually assist you in making connections, remembering difficult concepts, and studying for exams. Even though it may be tempting to stay up late cramming for your tests and exams, you will remember and perform better when you’ve had enough sleep.

Exercise

Consider you own sleep habits and answer the following questions:

- On average, how long do you sleep every night?

- Do you see a change in your ability to function when you haven’t had enough sleep?

- What could you do to limit the number of nights with too little sleep?

Memorization Techniques

Everyone wishes they had a better memory or a stronger way to use memorization. You can make the most of the memory you have by making some conscious decisions about how you study and prepare for exams and tests. Incorporating these memory techniques into your study sessions can help with information retention.

Using Mnemonics

Mnemonics (pronounced new-monics) are a way to remember things using reminders. Did you learn the points of the compass by remembering NEWS (north, east, west, and south)? Or the notes on the music staff as FACE or EGBDF (every good boy does fine)? These are mnemonics. When you’re first learning something and you aren’t familiar with the foundational concepts, these help you bring up the information quickly, especially for multi-step processes or lists. After you’ve worked in that discipline for a while, you likely don’t need the mnemonics, but you probably won’t forget them either.

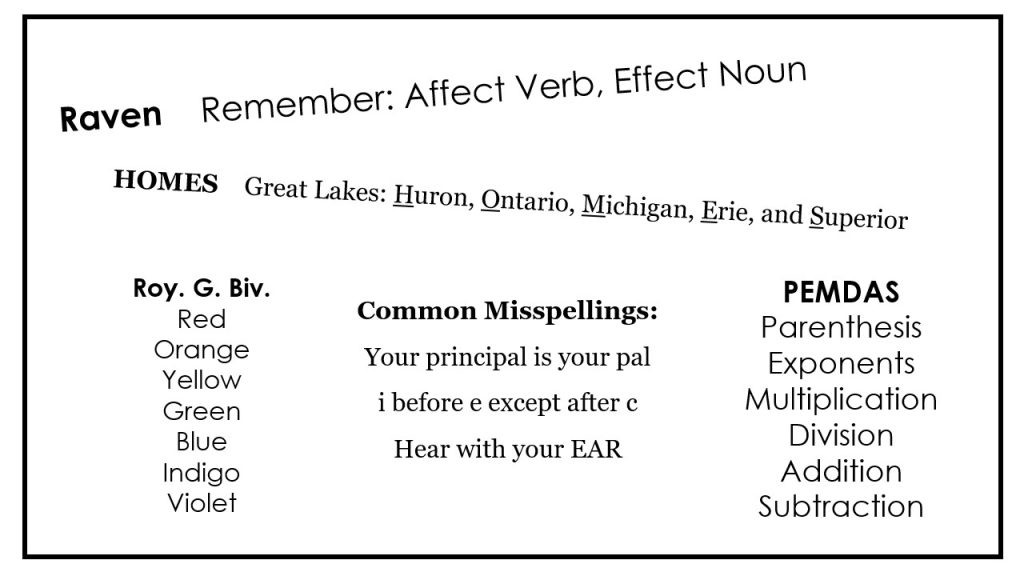

Here are some familiar mnemonics you may find useful:

Exercise

Reflect on the memorization strategies you use or have used in the past and answer the following questions:

- Do you have other mnemonics that help you remember difficult material?

- What are they?

- How have they helped you with remembering important things?

Generating Idea Clusters

Like mnemonics, idea clusters are a way to help your brain recall specific information by connecting it to other knowledge you already have. For example, you can remember the elements of the periodic table by singing the names to a familiar song. When you sit down to the test or exam you can sing the song and recreate the periodic table on your exam paper so that it is ready for you to use to answer the questions of the exam.

Practicing Concept Association

Concept association helps us connect ideas that we want to remember with existing information we already know. In this way we are linking the new information to some old information that is already secure in our memory. This allows us to more easily recall the new information because it is organized in our brain where we can find it.

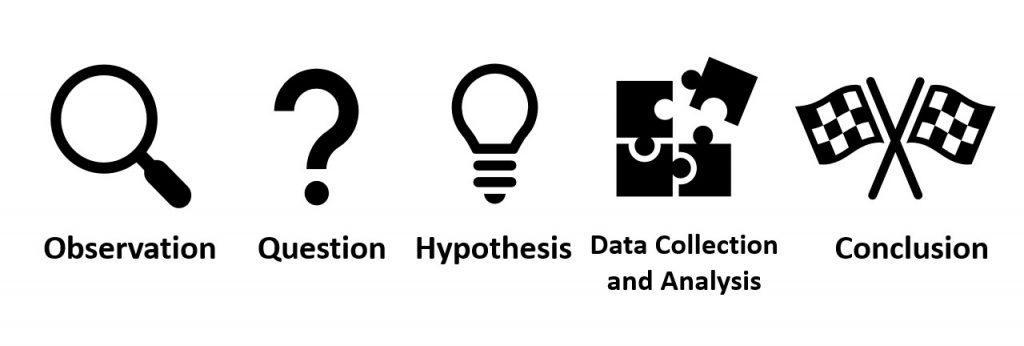

One method for concept association involves using an image to help us understand new vocabulary. For example, if we were trying to memorize the scientific method we could associate an image for each of the sections of the method.[2]

Key Takeaways

Understanding how your short- and long-term memory works will help you improve your memorization skills. You can use memorization strategies to help retain information so that you can access the information you need when completing tests and exams.

Attribution Statement: Adapted from College Success by Amy Baldwin, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.