Chapter 4: Linear Kinetics, Force and Newton’s Laws of Motion

4.9 Drag Forces

Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

Adapted by: Rob Pryce, Alix Blacklin

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Express mathematically the drag force.

- Discuss the applications of drag force.

- Define terminal velocity.

- Determine the terminal velocity given mass.

Another interesting force in everyday life is the force of drag on an object when it is moving in a fluid (either a gas or a liquid). You feel the drag force when you move your hand through water. You might also feel it if you move your hand during a strong wind. The faster you move your hand, the harder it is to move. You feel a smaller drag force when you tilt your hand so only the side goes through the air—you have decreased the area of your hand that faces the direction of motion. Like friction, the drag force always opposes the motion of an object. Unlike simple friction, the drag force is proportional to some function of the velocity of the object in that fluid. This functionality is complicated and depends upon the shape of the object, its size, its velocity, and the fluid it is in.

For most large objects such as bicyclists, cars, and baseballs not moving too slowly, the magnitude of the drag force [latex]{F}_{\text{D}}[/latex] is found to be proportional to the square of the speed of the object. We can write this relationship mathematically as [latex]{F}_{\text{D}}\propto \phantom{\rule{0.15em}{0ex}}{v}^{2}[/latex]. When taking into account other factors, this relationship becomes

[latex]{F}_{\text{D}}=\frac{1}{2}C\rho {\text{Av}}^{2}\text{,}[/latex]

where [latex]C[/latex] is the drag coefficient, [latex]A[/latex] is the area of the object facing the fluid, and [latex]\rho[/latex] is the density of the fluid. (Recall that density is mass per unit volume.) This equation can also be written in a more generalized fashion as [latex]{F}_{\text{D}}={\text{bv}}^{2}[/latex], where [latex]b[/latex] is a constant equivalent to [latex]0\text{.5}\mathrm{C\rho A}[/latex]. We have set the exponent for these equations as 2 because, when an object is moving at high velocity through air, the magnitude of the drag force is proportional to the square of the speed. For small particles moving at low speeds in a fluid, the exponent is equal to 1.

Drag Force

Drag force [latex]{F}_{\text{D}}[/latex] is found to be proportional to the square of the speed of the object. Mathematically

[latex]{F}_{\text{D}}\propto \phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{v}^{2}[/latex]

[latex]{F}_{\text{D}}=\frac{1}{2}\mathrm{C\rho }{\text{Av}}^{2}\text{,}[/latex]

where [latex]C[/latex] is the drag coefficient, [latex]A[/latex] is the area of the object facing the fluid, and [latex]\rho[/latex] is the density of the fluid.

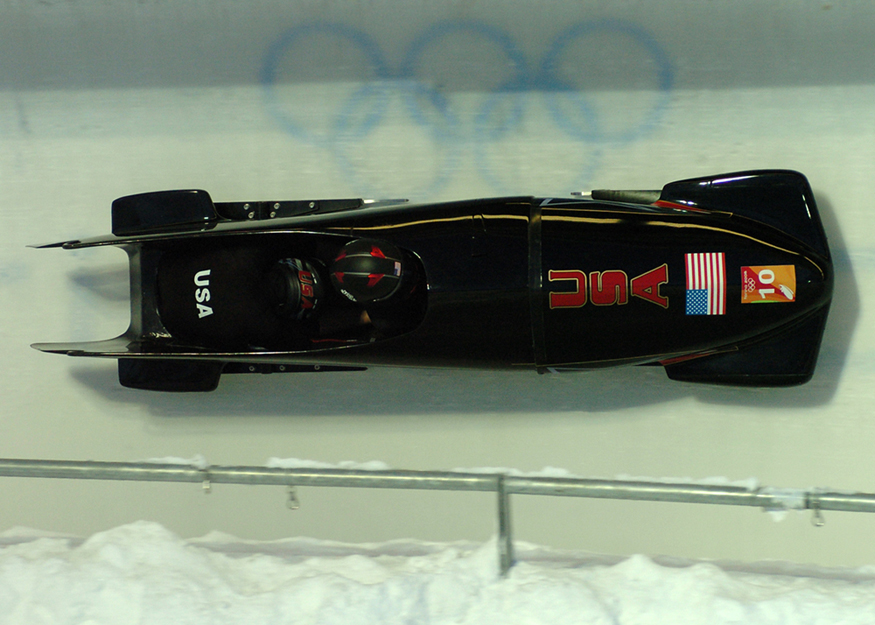

Athletes as well as car designers seek to reduce the drag force to lower their race times. (See Figure 4.7). “Aerodynamic” shaping of an automobile can reduce the drag force and so increase a car’s gas mileage.

The value of the drag coefficient, [latex]C[/latex] , is determined experimentally, usually with the use of a wind tunnel. (See Figure 4.8). Wind tunnels are becoming increasingly common in sport to help test different equipment or athletic positions.

The drag coefficient can depend upon velocity, but we will assume that it is a constant here. Table 6.2 lists some typical drag coefficients for a variety of objects. Notice that the drag coefficient is a dimensionless quantity. At highway speeds, over 50% of the power of a car is used to overcome air drag. Interestingly, the most fuel-efficient cruising speed is about 70–80 km/h (about 45–50 mi/h). For this reason, during the 1970s oil crisis in the United States, maximum speeds on highways were set at about 90 km/h (55 mi/h).

| Object | C |

|---|---|

| Airfoil | 0.05 |

| Toyota Camry | 0.28 |

| Ford Focus | 0.32 |

| Honda Civic | 0.36 |

| Ferrari Testarossa | 0.37 |

| Dodge Ram pickup | 0.43 |

| Sphere | 0.45 |

| Hummer H2 SUV | 0.64 |

| Skydiver (feet first) | 0.70 |

| Bicycle | 0.90 |

| Skydiver (horizontal) | 1.0 |

| Circular flat plate | 1.12 |

Substantial research is under way in the sporting world to minimize drag. The dimples on golf balls are being redesigned as are the clothes that athletes wear. Bicycle racers and some swimmers and runners wear full bodysuits. Australian Cathy Freeman wore a full body suit in the 2000 Sydney Olympics, and won the gold medal for the 400 m race. Many swimmers in the 2008 Beijing Olympics wore (Speedo) body suits; it might have made a difference in breaking many world records (See Figure 4.9). Most elite swimmers (and cyclists) shave their body hair. Such innovations can have the effect of slicing away milliseconds in a race, sometimes making the difference between a gold and a silver medal. One consequence is that careful and precise guidelines must be continuously developed to maintain the integrity of the sport.

Terminal Velocity

Some interesting situations connected to Newton’s second law occur when considering the effects of drag forces upon a moving object. For instance, consider a skydiver falling through air under the influence of gravity. The two forces acting on them are the force of gravity and the drag force (ignoring the buoyant force). The downward force of gravity remains constant regardless of the velocity at which the person is moving. However, as the person’s velocity increases, the magnitude of the drag force increases until the magnitude of the drag force is equal to the gravitational force, thus producing a net force of zero. A zero net force means that there is no acceleration, as given by Newton’s second law. At this point, the person’s velocity remains constant and we say that the person has reached his terminal velocity [latex]{v}_{t}[/latex]). Since [latex]{F}_{\text{D}}[/latex] is proportional to the speed, a heavier skydiver must go faster for [latex]{F}_{\text{D}}[/latex] to equal his weight. Let’s see how this works out using calculations:

At the terminal velocity,

[latex]{F}_{\text{net}}=\text{mg}-{F}_{\text{D}}=\text{ma}=0\text{.}[/latex]

Thus,

[latex]\text{mg}={F}_{\text{D}}\text{.}[/latex]

Using the equation for drag force, we have

[latex]\text{mg}=\frac{1}{2}\rho {\text{CAv}}^{2}.[/latex]

Solving for the velocity, we obtain

[latex]v=\sqrt{\frac{2\text{mg}}{\rho \text{CA}}}.[/latex]

Assume the density of air is [latex]\rho =1\text{.}\text{21 kg}{\text{/m}}^{3}[/latex]. A 75-kg skydiver descending head first will have an area approximately [latex]A=0\text{.}\text{18}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}[/latex] and a drag coefficient of approximately [latex]C=0\text{.}\text{70}[/latex]. We find that

[latex]\begin{array}{lll}v& =& \sqrt{\frac{2\left(\text{75 kg}\right)\left(9\text{.80 m}{\text{/s}}^{2}\right)}{\left(1\text{.}\text{21 kg}{\text{/m}}^{3}\right)\left(0\text{.}\text{70}\right)\left(\text{0.18}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}\right)}}\\ & =& \text{98 m/s}\\ & =& \text{350 km/h}\text{.}\end{array}[/latex]

This means a skydiver with a mass of 75 kg achieves a maximum terminal velocity of about 350 km/h while traveling in a headfirst position, minimizing the area and their drag. In a spread-eagle position, that terminal velocity may decrease to about 200 km/h as the area increases. This terminal velocity becomes much smaller after the parachute opens.

Example: A Terminal Velocity

Find the terminal velocity of an 85-kg skydiver falling in a spread-eagle position.

Strategy

At terminal velocity, [latex]{F}_{\text{net}}=0[/latex]. Thus the drag force on the skydiver must equal the force of gravity (the person’s weight). Using the equation of drag force, we find [latex]\text{mg}=\frac{1}{2}{\text{ρCAv}}^{2}[/latex].

Thus the terminal velocity [latex]{v}_{t}[/latex] can be written as

[latex]{v}_{\text{t}}=\sqrt{\frac{2\text{mg}}{\text{ρCA}}}.[/latex]

Solution

All quantities are known except the person’s projected area. This is an adult (85 kg) falling spread eagle. Using an approximate height and width, we can estimate the frontal area as:

Using our equation for [latex]{v}_{\text{t}}[/latex], we find that

[latex]\begin{array}{lll}{v}_{\text{t}}& =& \sqrt{\frac{2\left(\text{85}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{kg}\right)\left(9.80\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m/s}}^{2}\right)}{\left(1.21\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{kg/m}}^{3}\right)\left(1.0\right)\left(0.70\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}\right)}}\\ & =& \text{44 m/s.}\end{array}[/latex]

Discussion

This result is consistent with the value for [latex]{v}_{\text{t}}[/latex] mentioned earlier. The 75-kg skydiver going feet first had a [latex]v=\text{98 m}/\text{s}[/latex]. They weighed less but had a smaller frontal area and so a smaller drag due to the air.

Advanced Application

The size of the object that is falling through air presents another interesting application of air drag. If you fall from a 5-m high branch of a tree, you will likely get hurt—possibly fracturing a bone. However, a small squirrel does this all the time, without getting hurt. You don’t reach a terminal velocity in such a short distance, but the squirrel does.

The following interesting quote on animal size and terminal velocity is from a 1928 essay by a British biologist, J.B.S. Haldane, titled “On Being the Right Size. It also demonstrates an interesting application of biomechanics to the study of animal movement.

"To the mouse and any smaller animal, [gravity] presents practically no dangers. You can drop a mouse down a thousand-yard mine shaft; and, on arriving at the bottom, it gets a slight shock and walks away, provided that the ground is fairly soft. A rat is killed, a man is broken, and a horse splashes. For the resistance presented to movement by the air is proportional to the surface of the moving object. Divide an animal’s length, breadth, and height each by ten; its weight is reduced to a thousandth, but its surface only to a hundredth. So the resistance to falling in the case of the small animal is relatively ten times greater than the driving force."

The above quadratic dependence of air drag upon velocity does not hold if the object is very small, is going very slow, or is in a denser medium than air. Then we find that the drag force is proportional just to the velocity. This relationship is given by Stokes’ law, which states that

[latex]{F}_{\text{s}}=6\mathrm{\pi r\eta v},[/latex]

where [latex]r[/latex] is the radius of the object, [latex]\eta[/latex] is the viscosity of the fluid, and [latex]v[/latex] is the object’s velocity.

Good examples of this law are provided by microorganisms, pollen, and dust particles. Because each of these objects is so small, we find that many of these objects travel unaided only at a constant (terminal) velocity. Terminal velocities for bacteria (size about [latex]\text{1 μm}[/latex]) can be about [latex]\text{2 μm/s}[/latex]. To move at a greater speed, many bacteria swim using flagella. You'll likely learn about bacteria in other areas of kinesiology, for instance while studying pathology of infectious disease. Sediment in a lake also moves at a slow terminal velocity (about [latex]\text{5 μm/s}[/latex]), so it can take days to reach the bottom of the lake after being deposited on the surface.

If we compare animals living on land with those in water, you can see how drag has influenced evolution. Fishes, dolphins, and even massive whales are streamlined in shape to reduce drag forces. Birds are streamlined and migratory species that fly large distances often have particular features such as long necks. Flocks of birds fly in the shape of a spear head as the flock forms a streamlined pattern (see Figure 4.10). In humans, one important example of streamlining is the shape of sperm, which need to be efficient in their use of energy.