Chapter 7: Angular Kinematics

7.2 Angular Acceleration

Paul Peter Urone and Roger Hinrichs

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe uniform circular motion.

- Explain non-uniform circular motion.

- Calculate angular acceleration of an object.

- Observe the link between linear and angular acceleration.

Other sections in this chapter (Rotational Velocity, Centripetal Force and Acceleration, and Fictitious Forces) discuss only uniform circular motion, which is motion in a circle at constant speed and, hence, constant angular velocity. Recall that angular velocity [latex]\omega[/latex] was defined as the time rate of change of angle [latex]\theta[/latex]:

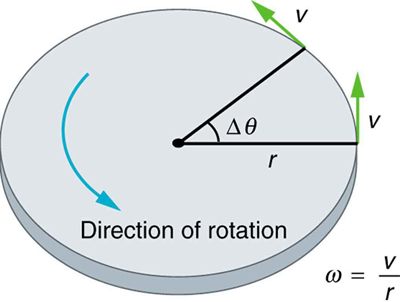

where [latex]\theta[/latex] is the angle of rotation as seen in the figure below. The relationship between angular velocity [latex]\omega[/latex] and linear velocity [latex]v[/latex] was also defined in Chapter 7.1: Rotation Angle and Angular Velocity as

or

where [latex]r[/latex] is the radius of curvature, also seen in the figure below. According to the sign convention, the counter clockwise direction is considered as positive direction and clockwise direction as negative

Angular velocity is not constant when a skater pulls in her arms, when a child starts up a merry-go-round from rest, or when a computer’s hard disk slows to a halt when switched off. In all these cases, there is an angular acceleration, in which [latex]\omega[/latex] changes. The faster the change occurs, the greater the angular acceleration. Angular acceleration [latex]\alpha[/latex] is defined as the rate of change of angular velocity. In equation form, angular acceleration is expressed as follows:

where [latex]\Delta \omega[/latex] is the change in angular velocity and [latex]\Delta t[/latex] is the change in time. The units of angular acceleration are [latex]\left(\text{rad/s}\right)\text{/s}[/latex], or [latex]{\text{rad/s}}^{2}[/latex]. If [latex]\omega[/latex] increases, then [latex]\alpha[/latex] is positive. If [latex]\omega[/latex] decreases, then [latex]\alpha[/latex] is negative.

Example: Calculating the Angular Acceleration and Deceleration of a Bike Wheel

Suppose a teenager puts her bicycle on its back and starts the rear wheel spinning from rest to a final angular velocity of 250 rpm in 5.00 s.

(a) Calculate the angular acceleration in [latex]{\text{rad/s}}^{2}[/latex].

(b) If she now slams on the brakes, causing an angular acceleration of [latex]–87.3\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{rad/s}}^{2}[/latex], how long does it take the wheel to stop?

Strategy for (a)

The angular acceleration can be found directly from its definition in [latex]\alpha =\frac{\Delta \omega }{\Delta t}[/latex] because the final angular velocity and time are given. We see that [latex]\Delta \omega[/latex] is 250 rpm and [latex]\Delta t[/latex] is 5.00 s.

Solution for (a)

Entering known information into the definition of angular acceleration, we get

Because [latex]\Delta \omega[/latex] is in revolutions per minute (rpm) and we want the standard units of [latex]{\text{rad/s}}^{2}[/latex] for angular acceleration, we need to convert [latex]\Delta \omega[/latex] from rpm to rad/s:

Entering this quantity into the expression for [latex]\alpha[/latex], we get

Strategy for (b)

In this part, we know the angular acceleration and the initial angular velocity. We can find the stoppage time by using the definition of angular acceleration and solving for [latex]\Delta t[/latex], yielding

Solution for (b)

Here the angular velocity decreases from [latex]\text{26.2 rad/s}[/latex] (250 rpm) to zero, so that [latex]\Delta \omega[/latex] is [latex]–\text{26.2 rad/s}[/latex], and [latex]\alpha[/latex] is given to be [latex]–\text{87.3}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{rad/s}}^{2}[/latex]. Thus,

Discussion

Note that the angular acceleration as the girl spins the wheel is small and positive; it takes 5 s to produce an appreciable angular velocity. When she hits the brake, the angular acceleration is large and negative. The angular velocity quickly goes to zero. In both cases, the relationships are analogous to what happens with linear motion. For example, there is a large deceleration when you crash into a brick wall—the velocity change is large in a short time interval.

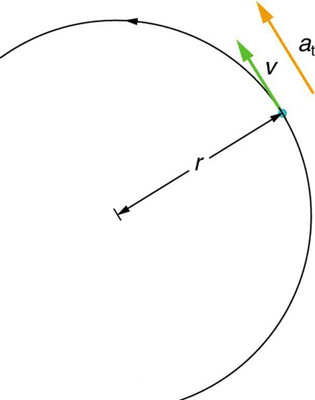

If the bicycle in the preceding example had been on its wheels instead of upside-down, it would first have accelerated along the ground and then come to a stop. This connection between circular motion and linear motion needs to be explored. For example, it would be useful to know how linear and angular acceleration are related. In circular motion, linear acceleration is tangent to the circle at the point of interest, as seen in the figure below. Thus, linear acceleration is called tangential acceleration [latex]{a}_{\text{t}}[/latex].

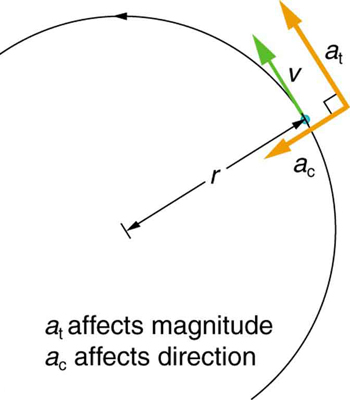

Linear or tangential acceleration refers to changes in the magnitude of velocity but not its direction. We know from other sections in this chapter (Rotational Velocity, Centripetal Force and Acceleration, and Fictitious Forces) that in circular motion centripetal acceleration, [latex]{a}_{\text{c}}[/latex], refers to changes in the direction of the velocity but not its magnitude. An object undergoing circular motion experiences centripetal acceleration, as seen in the figure below. Thus, [latex]{a}_{\text{t}}[/latex] and [latex]{a}_{\text{c}}[/latex] are perpendicular and independent of one another. Tangential acceleration [latex]{a}_{\text{t}}[/latex] is directly related to the angular acceleration [latex]\alpha[/latex] and is linked to an increase or decrease in the velocity, but not its direction.

Now we can find the exact relationship between linear acceleration [latex]{a}_{\text{t}}[/latex] and angular acceleration [latex]\alpha[/latex]. Because linear acceleration is proportional to a change in the magnitude of the velocity, it is defined (as it was in Chapter 2) to be

For circular motion, note that [latex]v=\mathrm{r\omega }[/latex], so that

The radius [latex]r[/latex] is constant for circular motion, and so [latex]\text{Δ}\left(\mathrm{r\omega }\right)=r\left(\Delta \omega \right)[/latex]. Thus,

By definition, [latex]\alpha =\frac{\Delta \omega }{\Delta t}[/latex]. Thus,

or

These equations mean that linear acceleration and angular acceleration are directly proportional. The greater the angular acceleration is, the larger the linear (tangential) acceleration is, and vice versa. For example, the greater the angular acceleration of a car’s drive wheels, the greater the acceleration of the car. The radius also matters. For example, the smaller a wheel, the smaller its linear acceleration for a given angular acceleration [latex]\alpha[/latex].

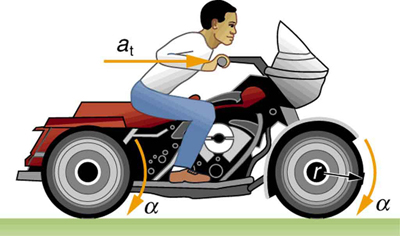

Example: Calculating the Angular Acceleration of a Motorcycle Wheel

A powerful motorcycle can accelerate from 0 to 30.0 m/s (about 108 km/h) in 4.20 s. What is the angular acceleration of its 0.320-m-radius wheels? (See the figure below)

Strategy

We are given information about the linear velocities of the motorcycle. Thus, we can find its linear acceleration [latex]{a}_{\text{t}}[/latex]. Then, the expression [latex]\alpha =\frac{{a}_{\text{t}}}{r}[/latex] can be used to find the angular acceleration.

Solution

The linear acceleration is

We also know the radius of the wheels. Entering the values for [latex]{a}_{\text{t}}[/latex] and [latex]r[/latex] into [latex]\alpha =\frac{{a}_{\text{t}}}{r}[/latex], we get

Discussion

Units of radians are dimensionless and appear in any relationship between angular and linear quantities.

So far, we have defined three rotational quantities— [latex]\theta \mathrm{, }\omega[/latex], and [latex]\alpha[/latex]. These quantities are analogous to the translational quantities [latex]x\mathrm{, }v[/latex], and [latex]a[/latex]. The table below displays rotational quantities, the analogous translational quantities, and the relationships between them.

| Rotational | Translational | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| [latex]\theta[/latex] | [latex]x[/latex] | [latex]\theta =\frac{x}{r}[/latex] |

| [latex]\omega[/latex] | [latex]v[/latex] | [latex]\omega =\frac{v}{r}[/latex] |

| [latex]\alpha[/latex] | [latex]a[/latex] | [latex]\alpha =\frac{{a}_{t}}{r}[/latex] |

Sit down with your feet on the ground on a chair that rotates. Lift one of your legs such that it is unbent (straightened out). Using the other leg, begin to rotate yourself by pushing on the ground. Stop using your leg to push the ground but allow the chair to rotate. From the origin where you began, sketch the angle, angular velocity, and angular acceleration of your leg as a function of time in the form of three separate graphs. Estimate the magnitudes of these quantities.

Check Your Understanding

Angular acceleration is a vector, having both magnitude and direction. How do we denote its magnitude and direction? Illustrate with an example.

Solution: The magnitude of angular acceleration is [latex]\alpha[/latex] and its most common units are [latex]{\text{rad/s}}^{2}[/latex]. The direction of angular acceleration along a fixed axis is denoted by a + or a – sign, just as the direction of linear acceleration in one dimension is denoted by a + or a – sign. For example, consider a gymnast doing a forward flip. Her angular momentum would be parallel to the mat and to her left. The magnitude of her angular acceleration would be proportional to her angular velocity (spin rate) and her moment of inertia about her spin axis.

Join the ladybug in an exploration of rotational motion. Rotate the merry-go-round to change its angle, or choose a constant angular velocity or angular acceleration. Explore how circular motion relates to the bug's x,y position, velocity, and acceleration using vectors or graphs.