Chapter 6: Linear Momentum and Collisions

6.3 Conservation of Momentum

Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

Adapted by: Rob Pryce, Alix Blacklin

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the principle of conservation of momentum.

- Derive an expression for the conservation of momentum.

- Explain conservation of momentum with examples.

- Explain the principle of conservation of momentum as it relates to atomic and subatomic particles.

Momentum is an important quantity because it is conserved. Yet it was not conserved in all of the examples in the previous sections, where large changes in momentum were produced by forces acting on the system of interest. Under what circumstances is momentum conserved?

The answer to this question entails considering a sufficiently large system. It is always possible to find a larger system in which total momentum is constant, even if momentum changes for components of the system. If a football player runs into the goalpost in the end zone, there will be a force on him that causes him to bounce backward. However, the Earth also recoils —conserving momentum—because of the force applied to it through the goalpost. Because Earth is many orders of magnitude more massive than the player, its recoil is immeasurably small and can be neglected in any practical sense, but it is real nevertheless.

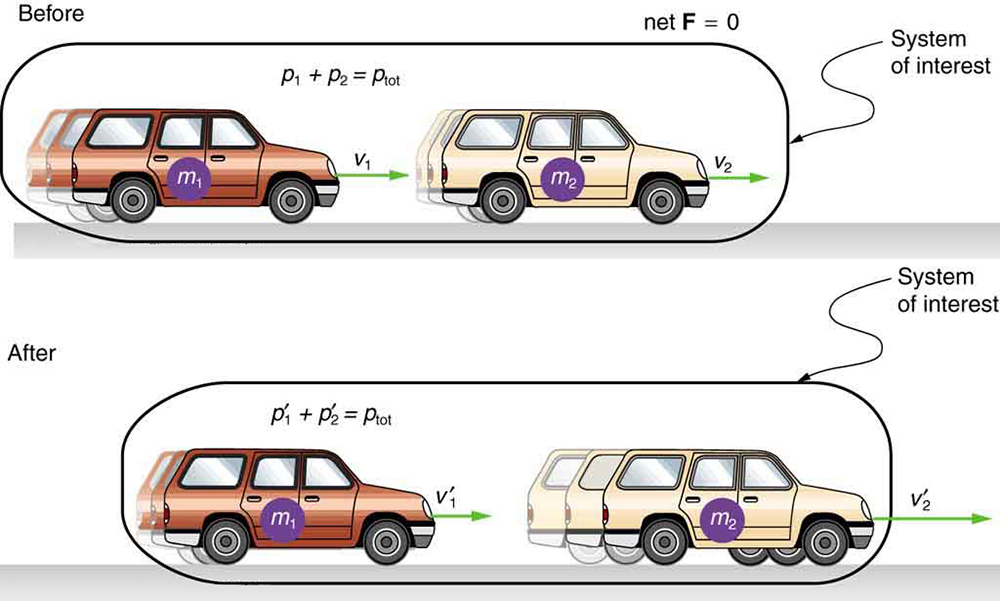

Consider what happens if the masses of two colliding objects are more similar than the masses of a football player and Earth—for example, one car bumping into another, as shown in the figure below. Both cars are coasting in the same direction when the lead car (labeled [latex]{m}_{2}[/latex]) is bumped by the trailing car (labeled [latex]{m}_{1}.[/latex]) The only unbalanced force on each car is the force of the collision. (Assume that the effects due to friction are negligible.) Car 1 slows down as a result of the collision, losing some momentum, while car 2 speeds up and gains some momentum. We shall now show that the total momentum of the two-car system remains constant.

Using the definition of impulse, the change in momentum of car 1 is given by

where [latex]{F}_{1}[/latex] is the force on car 1 due to car 2, and [latex]\Delta t[/latex] is the time the force acts (the duration of the collision). Intuitively, it seems obvious that the collision time is the same for both cars, but it is only true for objects traveling at ordinary speeds. (This assumption must be modified for objects travelling near the speed of light, but that is not encountered in the field of biomechanics)

Similarly, the change in momentum of car 2 is

where [latex]{F}_{2}[/latex] is the force on car 2 due to car 1, and we assume the duration of the collision [latex]\Delta t[/latex] is the same for both cars. We know from Newton’s third law that [latex]{F}_{2}=\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}–{F}_{1}[/latex], and so

Thus, the changes in momentum are equal and opposite, and

Because the changes in momentum add to zero, the total momentum of the two-car system is constant. That is,

where [latex]{p\prime }_{1}[/latex] and [latex]{p\prime }_{2}[/latex] are the momenta of cars 1 and 2 after the collision. (We often use primes to denote the final state.)

This result—that momentum is conserved—has validity far beyond the preceding one-dimensional case. It can be similarly shown that total momentum is conserved for any isolated system, with any number of objects in it. In equation form, the conservation of momentum principle for an isolated system is written

or

where [latex]{\mathbf{p}}_{\text{tot}}[/latex] is the total momentum (the sum of the momenta of the individual objects in the system) and [latex]{\mathbf{\text{p}}\prime }_{\text{tot}}[/latex] is the total momentum some time later. (The total momentum can be shown to be the momentum of the center of mass of the system.) An isolated system is defined to be one for which the net external force is zero [latex]\left({\mathbf{\text{F}}}_{\text{net}}=0\right)\text{.}[/latex]

Conservation of Momentum Principle

Isolated System

An isolated system is defined to be one for which the net external force is zero [latex]\left({\mathbf{\text{F}}}_{\text{net}}=0\right)\text{.}[/latex]

Perhaps an easier way to see that momentum is conserved for an isolated system is to consider Newton’s second law in terms of momentum, [latex]{\mathbf{F}}_{\text{net}}=\frac{{\Delta \mathbf{p}}_{\text{tot}}}{\Delta t}[/latex]. For an isolated system, [latex]\left({\mathbf{\text{F}}}_{\text{net}}=0\right)[/latex]; thus, [latex]\Delta {\mathbf{p}}_{\text{tot}}=0[/latex], and [latex]{\mathbf{p}}_{\text{tot}}[/latex] is constant.

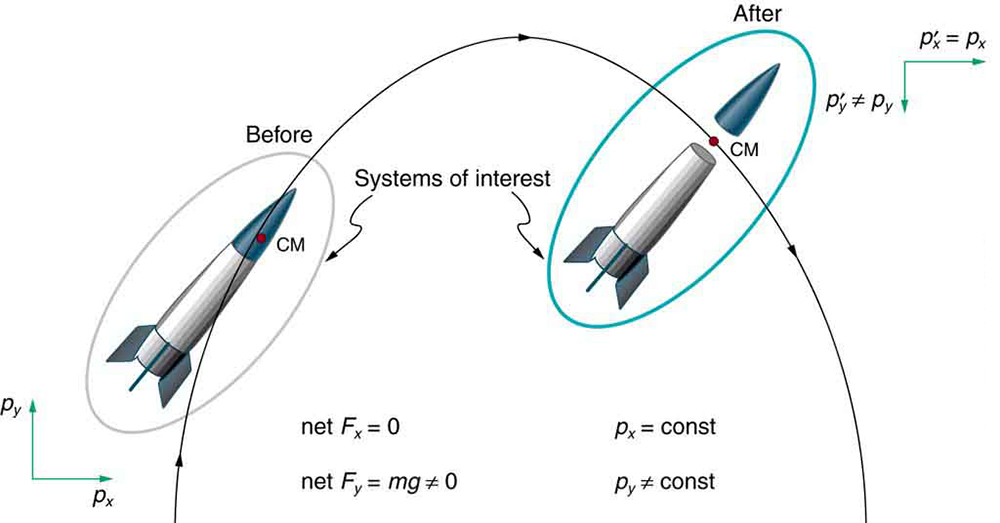

We have noted that the three length dimensions in nature—[latex]x[/latex], [latex]y[/latex], and [latex]z[/latex]—are independent, and it is interesting to note that momentum can be conserved in different ways along each dimension. For example, during projectile motion and where air resistance is negligible, momentum is conserved in the horizontal direction because horizontal forces are zero and momentum is unchanged. But along the vertical direction, the net vertical force is not zero and the momentum of the projectile is not conserved. (See the figure below.) However, if the momentum of the projectile-Earth system is considered in the vertical direction, we find that the total momentum is conserved.

The conservation of momentum principle can be applied to systems as different as two athletes colliding in sport and a gas containing huge numbers of atoms and molecules. Conservation of momentum is violated only when the net external force is not zero. But another larger system can always be considered in which momentum is conserved by simply including the source of the external force. For example, in the collision of two cars considered above, the two-car system conserves momentum while each one-car system does not.

Making Connections: Take-Home Investigation—Drop of Tennis Ball and a Basketball

Hold a tennis ball side by side and in contact with a basketball. Drop the balls together. (Be careful!) What happens? Explain your observations. Now hold the tennis ball above and in contact with the basketball. What happened? Explain your observations. What do you think will happen if the basketball ball is held above and in contact with the tennis ball?

Making Connections: Take-Home Investigation—Two Tennis Balls in a Ballistic Trajectory

Tie two tennis balls together with a string about a foot long. Hold one ball and let the other hang down and throw it in a ballistic trajectory. Explain your observations. Now mark the center of the string with bright ink or attach a brightly colored sticker to it and throw again. What happened? Explain your observations.

Examples of Conservation of Momentum

Some aquatic animals such as jellyfish move around based on the principles of conservation of momentum. A jellyfish fills its umbrella section with water and then pushes the water out resulting in motion in the opposite direction to that of the jet of water. Squids propel themselves in a similar manner but, in contrast with jellyfish, are able to control the direction in which they move by aiming their nozzle forward or backward. Typical squids can move at speeds of 8 to 12 km/h.

The ballistocardiograph (BCG) was a diagnostic tool used in the second half of the 20th century to study the strength of the heart. About once a second, your heart beats, forcing blood into the aorta. A force in the opposite direction is exerted on the rest of your body (recall Newton’s third law). A ballistocardiograph is a device that can measure this reaction force. This measurement is done by using a sensor (resting on the person) or by using a moving table suspended from the ceiling. This technique can gather information on the strength of the heart beat and the volume of blood passing from the heart. However, the electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) and the echocardiogram (cardiac ECHO or ECHO; a technique that uses ultrasound to see an image of the heart) are more widely used in the practice of cardiology.

The conservation of momentum principle not only applies to the macroscopic objects, it is also essential to our explorations of atomic and subatomic particles. Giant machines hurl subatomic particles at one another, and researchers evaluate the results by assuming conservation of momentum (among other things).

On the small scale, we find that particles and their properties are invisible to the naked eye but can be measured with our instruments, and models of these subatomic particles can be constructed to describe the results. Momentum is found to be a property of all subatomic particles including massless particles such as photons that compose light. Momentum being a property of particles hints that momentum may have an identity beyond the description of an object’s mass multiplied by the object’s velocity. Indeed, momentum relates to wave properties and plays a fundamental role in what measurements are taken and how we take these measurements. Furthermore, we find that the conservation of momentum principle is valid when considering systems of particles. We use this principle to analyze the masses and other properties of previously undetected particles, such as the nucleus of an atom and the existence of quarks that make up particles of nuclei.

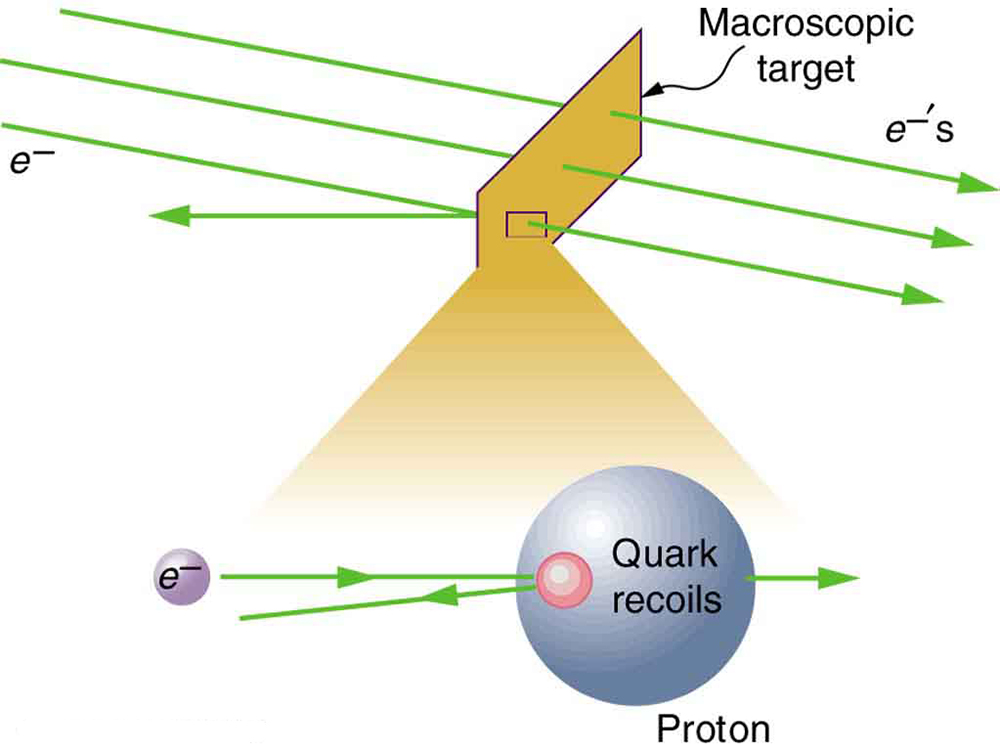

The figure below illustrates how a particle scattering backward from another implies that its target is massive and dense. Experiments seeking evidence that quarks make up protons (one type of particle that makes up nuclei) scattered high-energy electrons off of protons (nuclei of hydrogen atoms). Electrons occasionally scattered straight backward in a manner that implied a very small and very dense particle makes up the proton—this observation is considered nearly direct evidence of quarks. The analysis was based partly on the same conservation of momentum principle that works so well on the large scale.