Chapter 4: Linear Kinetics, Force and Newton’s Laws of Motion

4.10 Elasticity: Stress and Strain

Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

Adapted by: Rob Pryce, Alix Blacklin

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State Hooke’s law.

- Explain Hooke’s law using graphical representation between deformation and applied force.

- Discuss the three types of deformations such as changes in length, sideways shear and changes in volume.

- Describe with examples the young’s modulus, shear modulus and bulk modulus.

- Determine the change in length given mass, length and radius.

We now move from consideration of forces that affect the motion of an object (such as friction and drag) to those that affect an object’s shape. If a bulldozer pushes a car into a wall, the car will not move but it will noticeably change shape. A change in shape due to the application of a force is a deformation. Even very small forces are known to cause some deformation. For small deformations, two important characteristics are observed. First, the object returns to its original shape when the force is removed—that is, the deformation is elastic for small deformations. Second, the size of the deformation is proportional to the force—that is, for small deformations, Hooke’s law is obeyed. In equation form, Hooke’s law is given by

[latex]F=k\Delta L,[/latex]

where [latex]\Delta L[/latex] is the amount of deformation (the change in length, for example) produced by the force [latex]F[/latex], and [latex]k[/latex] is a proportionality constant that depends on the shape and composition of the object and the direction of the force. Note that this force is a function of the deformation [latex]\Delta L[/latex] —it is not constant as a kinetic friction force is. Rearranging this to

[latex]\Delta L=\frac{F}{k}[/latex]

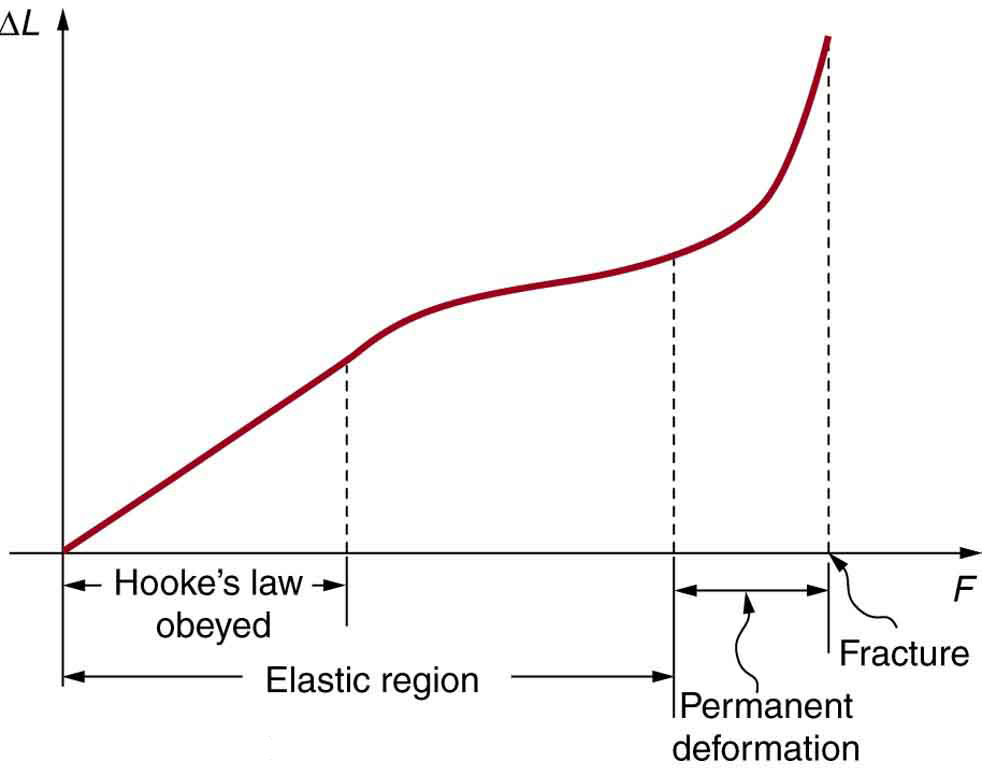

makes it clear that the deformation is proportional to the applied force. Figure 4.11 shows the Hooke’s law relationship between the extension [latex]\Delta L[/latex] of a spring or of a human bone. For metals or springs, the straight line region in which Hooke’s law pertains is much larger. Bones are brittle and the elastic region is small and the fracture abrupt. Eventually a large enough stress to the material will cause it to break or fracture. Tensile strength is the breaking stress that will cause permanent deformation or fracture of a material.

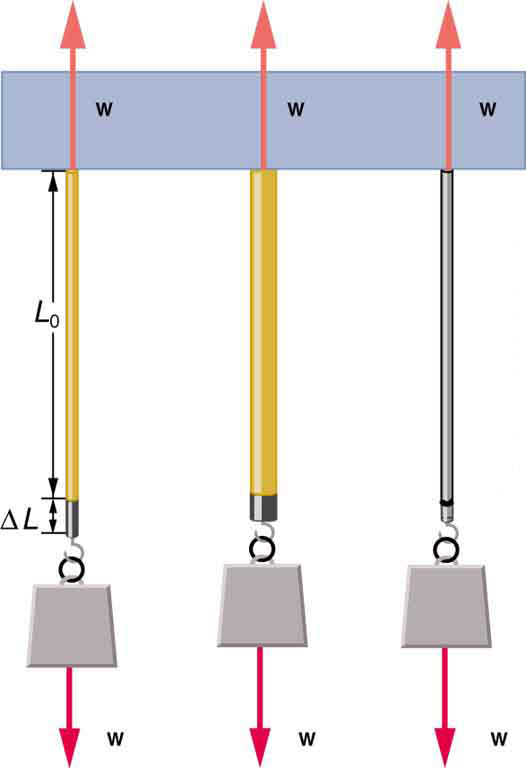

The proportionality constant [latex]k[/latex] depends upon a number of factors for the material. For example, a guitar string made of nylon stretches when it is tightened, and the elongation [latex]\Delta L[/latex] is proportional to the force applied (at least for small deformations). Thicker nylon strings and ones made of steel stretch less for the same applied force, implying they have a larger [latex]k[/latex] (see Figure 4.12). Finally, all three strings return to their normal lengths when the force is removed, provided the deformation is small. Most materials will behave in this manner if the deformation is less than about 0.1% or about 1 part in [latex]{\text{10}}^{3}[/latex].

How would you go about measuring the proportionality constant [latex]k[/latex] of a rubber band? If a rubber band stretched 3 cm when a 100-g mass was attached to it, then how much would it stretch if two similar rubber bands were attached to the same mass—even if put together in parallel or alternatively if tied together in series?

We now consider three specific types of deformations:

- changes in length (tension and compression),

- sideways shear (stress), and

- changes in volume.

All deformations are assumed to be small unless otherwise stated.

Changes in Length—Tension and Compression: Elastic Modulus

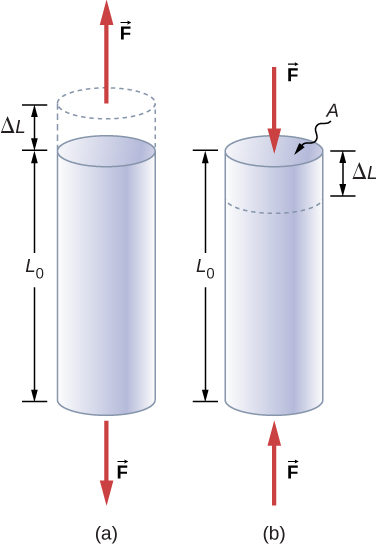

A change in length [latex]\Delta L[/latex] is produced when a force is applied to a wire or rod parallel to its length [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex], either stretching it (a tension) or compressing it. (See FIgure 4.13)

Experiments have shown that the change in length [latex]\Delta L[/latex]) depends on only a few variables. As already noted, [latex]\Delta L[/latex] is proportional to the force [latex]F[/latex] and depends on the substance from which the object is made. Additionally, the change in length is proportional to the original length [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex] and inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the wire or rod. For example, a long guitar string will stretch more than a short one, and a thick string will stretch less than a thin one. We can combine all these factors into one equation for [latex]\Delta L[/latex]:

[latex]\Delta L=\frac{1}{Y}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0},[/latex]

where [latex]\Delta L[/latex] is the change in length, [latex]F[/latex] the applied force, [latex]Y[/latex] is a factor, called the elastic modulus or Young’s modulus, that depends on the substance, [latex]A[/latex] is the cross-sectional area, and [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex] is the original length. Table 6.3 lists values of [latex]Y[/latex] for several materials—those with a large [latex]Y[/latex] are said to have a large tensile stiffness because they deform less for a given tension or compression.

| Material | Young’s modulus (tension–compression) Y (109 N/m2) |

Shear modulus S (109 N/m2) |

Bulk modulus B (109 N/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | 70 | 25 | 75 |

| Bone – tension | 16 | 80 | 8 |

| Bone – compression | 9 | ||

| Brass | 90 | 35 | 75 |

| Brick | 15 | ||

| Concrete | 20 | ||

| Glass | 70 | 20 | 30 |

| Granite | 45 | 20 | 45 |

| Hair (human) | 10 | ||

| Hardwood | 15 | 10 | |

| Iron, cast | 100 | 40 | 90 |

| Lead | 16 | 5 | 50 |

| Marble | 60 | 20 | 70 |

| Nylon | 5 | ||

| Polystyrene | 3 | ||

| Silk | 6 | ||

| Spider thread | 3 | ||

| Steel | 210 | 80 | 130 |

| Tendon | 1 | ||

| Acetone | 0.7 | ||

| Ethanol | 0.9 | ||

| Glycerin | 4.5 | ||

| Mercury | 25 | ||

| Water | 2.2 |

Note that there is an assumption that the object does not accelerate, so that there are actually two applied forces of magnitude [latex]F[/latex] acting in opposite directions. For example, the strings in Figure 4.13 are being pulled down by a force of magnitude [latex]w[/latex] and held up by the ceiling, which also exerts a force of magnitude [latex]w[/latex].

Example: Calculating Stretch. A simple example

Suspension cables are used to carry gondolas at ski resorts. (See Figure 4.13). Consider a suspension cable that includes an unsupported span of 3020 m. Calculate the amount of stretch in the steel cable. Assume that the cable has a diameter of 5.6 cm and the maximum tension it can withstand is [latex]3\text{.}0×{\text{10}}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{N}[/latex].

Strategy

The force is equal to the maximum tension, or [latex]F=3\text{.}0×{\text{10}}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{N}[/latex]. The cross-sectional area is [latex]{\mathrm{\pi r}}^{2}=2\text{.}\text{46}×{\text{10}}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}[/latex]. The equation [latex]\Delta L=\frac{1}{Y}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0}[/latex] can be used to find the change in length.

Solution

All quantities are known. Thus,

[latex]\begin{array}{lll}\Delta L& =& \left(\frac{1}{\text{210}×{\text{10}}^{9}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{N/m}}^{2}}\right)\left(\frac{3\text{.}0×{\text{10}}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{N}}{2.46×{10}^{–3}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}}\right)\left(\text{3020 m}\right)\\ & =& \text{18 m}.\end{array}[/latex]

Discussion

This is quite a stretch, but only about 0.6% of the unsupported length. Effects of temperature upon length might be important in these environments.

Bones, on the whole, do not fracture due to tension or compression. Rather they generally fracture due to sideways impact or bending, resulting in the bone shearing or snapping. The behavior of bones under tension and compression is important because it determines the load the bones can carry. Bones are classified as weight-bearing structures such as columns in buildings and trees. Weight-bearing structures have special features; columns in building have steel-reinforcing rods while trees and bones are fibrous. The bones in different parts of the body serve different structural functions and are prone to different stresses. Thus the bone in the top of the femur is arranged in thin sheets separated by marrow while in other places the bones can be cylindrical and filled with marrow or just solid.

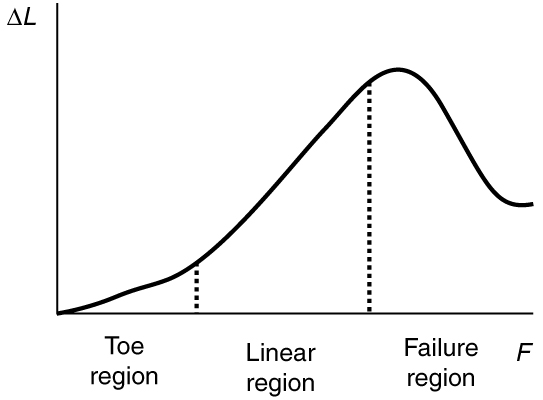

Another biological example of Hooke’s law occurs in tendons. Functionally, the tendon (the tissue connecting muscle to bone) must stretch easily at first when a force is applied, but offer a much greater restoring force for a greater strain. Figure 4.15 shows a stress-strain relationship for a human tendon. Some tendons have a high collagen content so there is relatively little strain, or length change; others, like support tendons (as in the leg) can change length up to 10%. Note that this stress-strain curve is nonlinear, since the slope of the line changes in different regions. In the first part of the stretch called the toe region, the fibers in the tendon begin to align in the direction of the stress—this is called uncrimping. In the linear region, the fibrils will be stretched, and in the failure region individual fibers begin to break. A simple model of this relationship can be illustrated by springs in parallel: different springs are activated at different lengths of stretch. Examples of this are given in the problems at end of this chapter. Ligaments (tissue connecting bone to bone) behave in a similar way.

Unlike bones and tendons, which need to be strong as well as elastic, the arteries and lungs need to be very stretchable. The elastic properties of the arteries are essential for blood flow. The pressure in the arteries increases and arterial walls stretch when the blood is pumped out of the heart. When the aortic valve shuts, the pressure in the arteries drops and the arterial walls relax to maintain the blood flow. When you feel your pulse, you are feeling exactly this—the elastic behavior of the arteries as the blood gushes through with each pump of the heart. If the arteries were rigid, you would not feel a pulse. The heart is also an organ with special elastic properties. The lungs expand with muscular effort when we breathe in but relax freely and elastically when we breathe out. Our skins are particularly elastic, especially for the young. A young person can go from 100 kg to 60 kg with no visible sag in their skins. The elasticity of all organs reduces with age. Gradual physiological aging through reduction in elasticity starts in the early 20s.

Example: Calculating Deformation: How Much Does Your Leg Shorten When You Stand on It?

Calculate the change in length of the upper leg bone (the femur) when a 70.0 kg man supports 62.0 kg of his mass on it, assuming the bone to be equivalent to a uniform rod that is 40.0 cm long and 2.00 cm in radius.

Strategy

The force is equal to the weight supported, or

[latex]F=\text{mg}=\left(\text{62}\text{.}0 kg\right)\left(9\text{.}\text{80 m}{\text{/s}}^{2}\right)=\text{607}\text{.}6 N,[/latex]

and the cross-sectional area is [latex]{\mathrm{\pi r}}^{2}=1\text{.}\text{257}×{\text{10}}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}[/latex].

The equation [latex]\Delta L=\frac{1}{Y}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0}[/latex] can be used to find the change in length.

Solution

All quantities except [latex]\Delta L[/latex] are known. Note that the compression value for Young’s modulus for bone must be used here. Thus,

[latex]\begin{array}{lll}\Delta L& =& \left(\frac{1}{9×{\text{10}}^{9}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{N/m}}^{2}}\right)\left(\frac{\text{607}\text{.}\text{6 N}}{1.\text{257}×{\text{10}}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}}\right)\left(0\text{.}\text{400 m}\right)\\ & =& 2×{\text{10}}^{-5}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m.}\end{array}[/latex]

Discussion

This small change in length seems reasonable, consistent with our experience that bones are rigid. In fact, even the rather large forces encountered during strenuous physical activity do not compress or bend bones by large amounts. Although bone is rigid compared with fat or muscle, several of the substances listed in Table 6.3 have larger values of Young’s modulus [latex]Y[/latex]. In other words, they are more rigid.

The equation for change in length is traditionally rearranged and written in the following form:

The ratio of force to area, [latex]\frac{F}{A}[/latex], is defined as stress (measured in [latex]{\text{N/m}}^{\text{2}}[/latex]), and the ratio of the change in length to length, [latex]\frac{\Delta L}{{L}_{0}}[/latex], is defined as strain (a unitless quantity). In other words,

[latex]\text{stress}=Y×\text{strain}.[/latex]

In this form, the equation is analogous to Hooke’s law, with stress analogous to force and strain analogous to deformation. If we again rearrange this equation to the form

we see that it is the same as Hooke’s law with a proportionality constant

This general idea—that force and the deformation it causes are proportional for small deformations—applies to changes in length, sideways bending, and changes in volume.

The ratio of force to area, [latex]\frac{F}{A}[/latex], is defined as stress measured in N/m2.

The ratio of the change in length to length, [latex]\frac{\Delta L}{{L}_{0}}[/latex], is defined as strain (a unitless quantity). In other words,

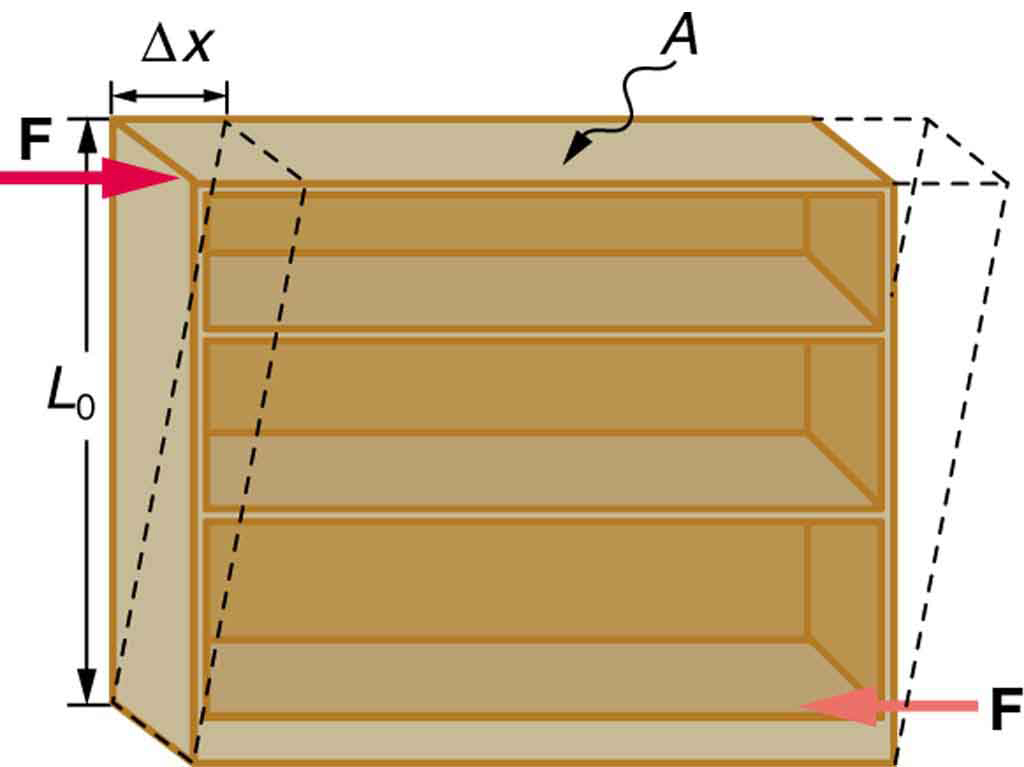

Figure 4.16 illustrates what is meant by a sideways stress or a shearing force. Here the deformation is called [latex]\Delta x[/latex] and it is perpendicular to [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex], rather than parallel as with tension and compression. Shear deformation behaves similarly to tension and compression and can be described with similar equations. The expression for shear deformation is

[latex]\Delta x=\frac{1}{S}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0},[/latex]

where [latex]S[/latex] is the shear modulus (see Table 6.3) and [latex]F[/latex] is the force applied perpendicular to [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex] and parallel to the cross-sectional area [latex]A[/latex]. Again, to keep the object from accelerating, there are actually two equal and opposite forces [latex]F[/latex] applied across opposite faces, as illustrated in Figure 4.16. The equation is logical—for example, it is easier to bend a long thin pencil (small [latex]A[/latex]) than a short thick one, and both are more easily bent than similar steel rods (large [latex]S[/latex]).

[latex]\Delta x=\frac{1}{S}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0},[/latex]

where [latex]S[/latex] is the shear modulus and [latex]F[/latex] is the force applied perpendicular to [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex] and parallel to the cross-sectional area [latex]A[/latex].

Examination of the shear moduli in Table 6.3 reveals some telling patterns. For example, shear moduli are less than Young’s moduli for most materials. Bone is a remarkable exception. Its shear modulus is not only greater than its Young’s modulus, but it is as large as that of steel. This is why bones are so rigid.

The spinal column (consisting of 26 vertebral segments separated by discs) provides the main support for the head and upper part of the body. The spinal column has normal curvature for stability, but this curvature can be increased, leading to increased shearing forces on the lower vertebrae. Discs are better at withstanding compressional forces than shear forces. Because the spine is not vertical, the weight of the upper body exerts some of both. Pregnant women and people that are overweight (with large abdomens) need to move their shoulders back to maintain balance, thereby increasing the curvature in their spine and so increasing the shear component of the stress. An increased angle due to more curvature increases the shear forces along the plane. These higher shear forces increase the risk of back injury through ruptured discs. The lumbosacral disc (the wedge shaped disc below the last vertebrae) is particularly at risk because of its location.

By contrast, the shear moduli for concrete and brick are very small; they are too highly variable to be listed. Concrete used in buildings can withstand compression, as in pillars and arches, but is very poor against shear, as might be encountered in heavily loaded floors or during earthquakes. Modern structures were made possible by the use of steel and steel-reinforced concrete. Almost by definition, liquids and gases have shear moduli near zero, because they flow in response to shearing forces.

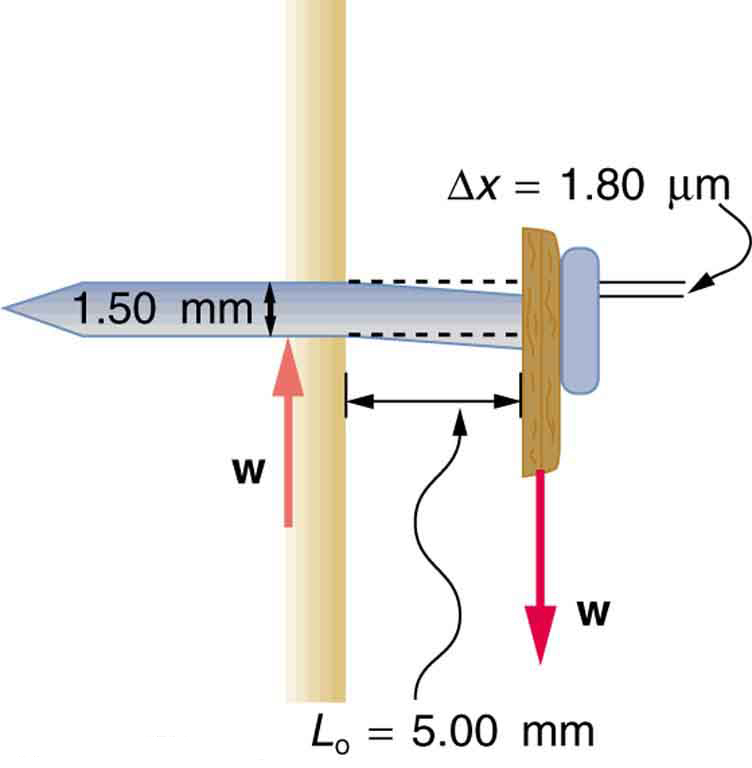

Example: Calculating Force Required to Deform: That Nail Does Not Bend Much Under a Load

Find the mass of the picture hanging from a steel nail as shown in Figure 4.17, given that the nail bends only [latex]\text{1.80 µm}[/latex]. (Assume the shear modulus is known to two significant figures.)

Strategy

The force [latex]F[/latex] on the nail (neglecting the nail’s own weight) is the weight of the picture [latex]w[/latex]. If we can find [latex]w[/latex], then the mass of the picture is just [latex]\frac{w}{g}[/latex] . The equation [latex]\Delta x=\frac{1}{S}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0}[/latex] can be solved for [latex]F[/latex].

Solution

Solving the equation [latex]\Delta x=\frac{1}{S}\frac{F}{A}{L}_{0}[/latex] for [latex]F[/latex], we see that all other quantities can be found:

[latex]F=\frac{\mathrm{SA}}{{L}_{0}}\Delta x.[/latex]

S is found in Table 6.3 and is [latex]S=\text{80}×{\text{10}}^{9}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{N/m}}^{2}[/latex]. The radius [latex]r[/latex] is 0.750 mm (as seen in the figure), so the cross-sectional area is

[latex]A={\mathrm{\pi r}}^{2}=1\text{.}\text{77}×{\text{10}}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}.[/latex]

The value for [latex]{L}_{0}[/latex] is also shown in the figure. Thus,

[latex]F=\frac{\left(\text{80}×{\text{10}}^{9}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{N/m}}^{2}\right)\left(1\text{.}\text{77}×{\text{10}}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{2}\right)}{\left(5\text{.}\text{00}×{\text{10}}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m}\right)}\left(1\text{.}\text{80}×{\text{10}}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{m}\right)=\text{51 N.}[/latex]

This 51 N force is the weight [latex]w[/latex] of the picture, so the picture’s mass is

[latex]m=\frac{w}{g}=\frac{F}{g}=5\text{.2 kg}.[/latex]

Discussion

This is a fairly massive picture, and it is impressive that the nail flexes only [latex]\text{1.80 µm}[/latex]—an amount undetectable to the unaided eye.

Changes in Volume: Bulk Modulus

Changes in volume are less frequently encountered in biomechanics, however an explanation is provided below for completeness.

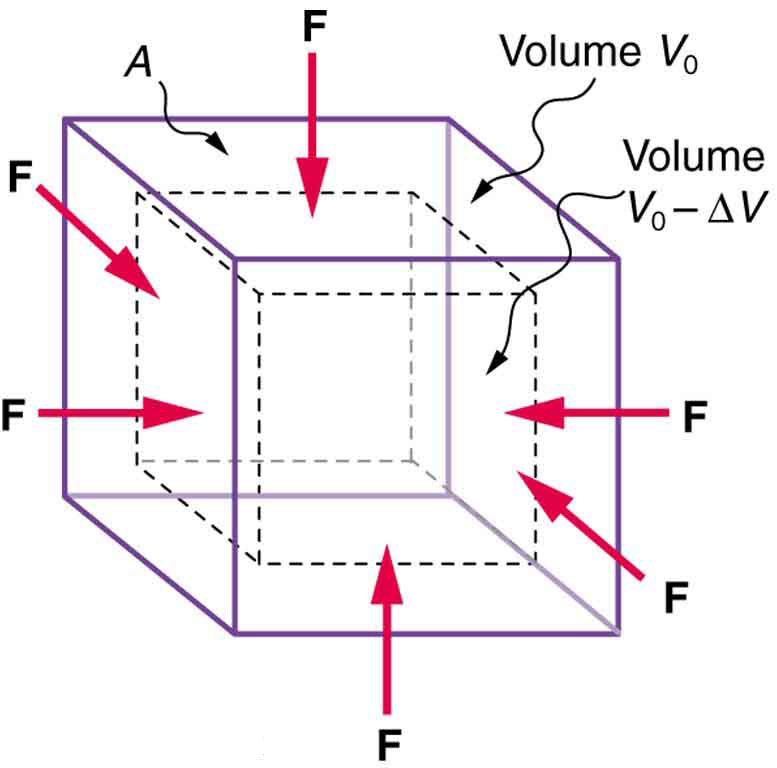

An object will be compressed in all directions if inward forces are applied evenly on all its surfaces as in Figure 5.18. It is relatively easy to compress gases and extremely difficult to compress liquids and solids. For example, air in a wine bottle is compressed when it is corked. But if you try corking a brim-full bottle, you cannot compress the wine—some must be removed if the cork is to be inserted. The reason for these different compressibilities is that atoms and molecules are separated by large empty spaces in gases but packed close together in liquids and solids. To compress a gas, you must force its atoms and molecules closer together. To compress liquids and solids, you must actually compress their atoms and molecules, and very strong electromagnetic forces in them oppose this compression.

We can describe the compression or volume deformation of an object with an equation. First, we note that a force “applied evenly” is defined to have the same stress, or ratio of force to area [latex]\frac{F}{A}[/latex] on all surfaces. The deformation produced is a change in volume [latex]\Delta V[/latex], which is found to behave very similarly to the shear, tension, and compression previously discussed. (This is not surprising, since a compression of the entire object is equivalent to compressing each of its three dimensions.) The relationship of the change in volume to other physical quantities is given by

[latex]\Delta V=\frac{1}{B}\frac{F}{A}{V}_{0},[/latex]

where [latex]B[/latex] is the bulk modulus (see Table 4.3), [latex]{V}_{0}[/latex] is the original volume, and [latex]\frac{F}{A}[/latex] is the force per unit area applied uniformly inward on all surfaces. Note that no bulk moduli are given for gases.

What are some examples of bulk compression of solids and liquids? One practical example is the manufacture of industrial-grade diamonds by compressing carbon with an extremely large force per unit area. The carbon atoms rearrange their crystalline structure into the more tightly packed pattern of diamonds. In nature, a similar process occurs deep underground, where extremely large forces result from the weight of overlying material. Another natural source of large compressive forces is the pressure created by the weight of water, especially in deep parts of the oceans. Water exerts an inward force on all surfaces of a submerged object, and even on the water itself. At great depths, water is measurably compressed, as the following example illustrates.

Example: Calculating Change in Volume with Deformation: How Much Is Water Compressed at Great Ocean Depths?

Calculate the fractional decrease in volume [latex]\frac{\Delta V}{{V}_{0}}[/latex] for seawater at 5.00 km depth, where the force per unit area is [latex]5\text{.}\text{00}×{\text{10}}^{7}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}N/{m}^{2}[/latex] .

Strategy

Equation [latex]\Delta V=\frac{1}{B}\frac{F}{A}{V}_{0}[/latex] is the correct physical relationship. All quantities in the equation except [latex]\frac{\Delta V}{{V}_{0}}[/latex] are known.

Solution

Solving for the unknown [latex]\frac{\Delta V}{{V}_{0}}[/latex] gives

[latex]\frac{\Delta V}{{V}_{0}}=\frac{1}{B}\frac{F}{A}.[/latex]

Substituting known values with the value for the bulk modulus [latex]B[/latex] from Table 4.3,

[latex]\frac{\Delta V}{{V}_{0}} = \frac{5.00×10^7\text{N/m}^{2}}{2.2×10^9\text{N/m}^{2}} = 0.023=2.3\text{%}[/latex]

Discussion

Although measurable, this is not a significant decrease in volume considering that the force per unit area is about 500 atmospheres (1 million pounds per square foot). Liquids and solids are extraordinarily difficult to compress.

Conversely, very large forces are created by liquids and solids when they try to expand but are constrained from doing so—which is equivalent to compressing them to less than their normal volume. This often occurs when a contained material warms up, since most materials expand when their temperature increases. If the materials are tightly constrained, they deform or break their container. Another very common example occurs when water freezes. Water, unlike most materials, expands when it freezes, and it can easily fracture a boulder, rupture a biological cell, or crack an engine block that gets in its way.