Chapter 3 Describing Movement in Two Dimensions, 2-D Linear Kinematics

3.2 Adding and Subtracting Vectors: Graphical

Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

Adapted by: Rob Pryce, Alix Blacklin

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the rules of vector addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

- Apply graphical methods of vector addition and subtraction to determine the displacement of moving objects.

Vectors in Two Dimensions

A vector is a quantity that has magnitude and direction. Displacement, velocity, acceleration, and force, for example, are all vectors. In one-dimensional, or straight-line, motion, the direction of a vector can be given simply by a plus or minus sign. In two dimensions (2-d), however, we specify the direction of a vector relative to some reference frame (i.e., coordinate system), using an arrow having length proportional to the vector’s magnitude and pointing in the direction of the vector.

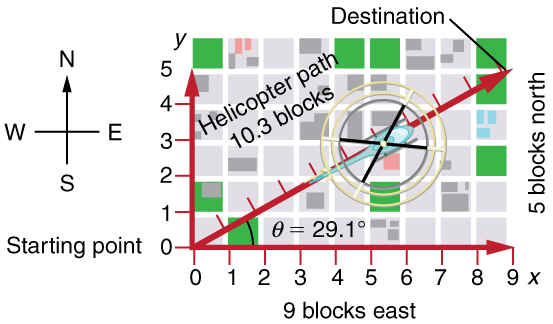

Figure 3.8 shows such a graphical representation of a vector, using as an example the total displacement for the person walking in a city considered in Kinematics in Two Dimensions: An Introduction. In written form, vectors can be represented two different ways. In this text we shall represent vectors by adding a arrow overtop of the quantity, such as [latex]\vec{A}[/latex], indicates a vector represented by the variable 'A'. Alternatively, vector quantities can be indicated using bold, such as [latex]\textbf{A}[/latex]. Finally, if we want to indicate the direction of a vector we use the Greek letter theta, [latex]\theta[/latex], and if we want to indicate only the magnitude of a vector, we can use italics, [latex]\textit{D}[/latex])

Vector Addition: Head-to-Tail Method

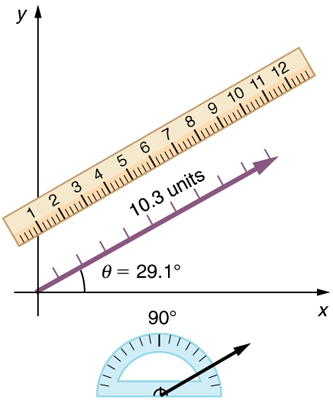

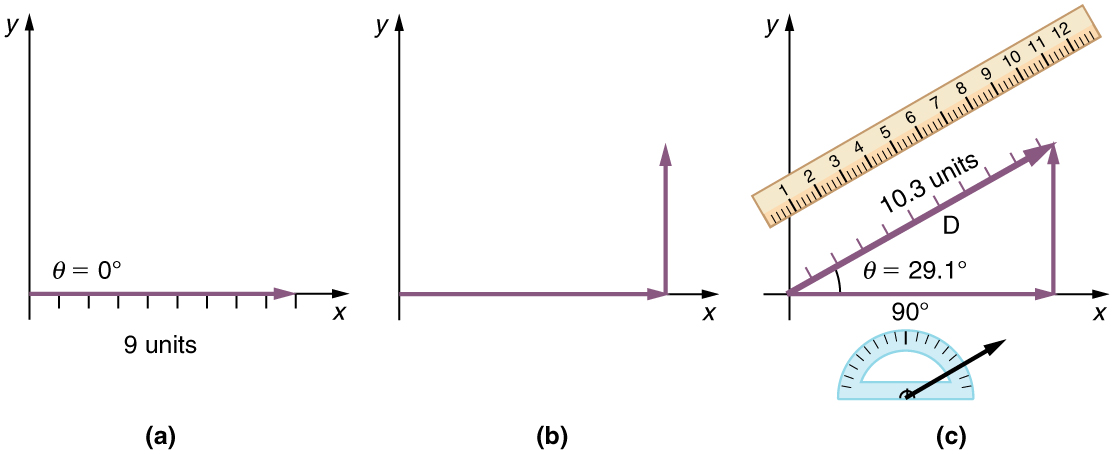

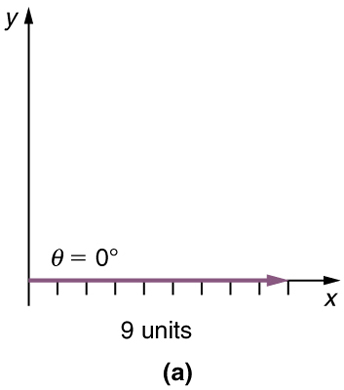

The head-to-tail method is a graphical way to add vectors, described in Figure 3.10 below and in the steps following. The tail of the vector is the starting point of the vector, and the head (or tip) of a vector is the final, pointed end of the arrow

Step 1.Draw an arrow to represent the first vector (9 blocks to the east) using a ruler and protractor.

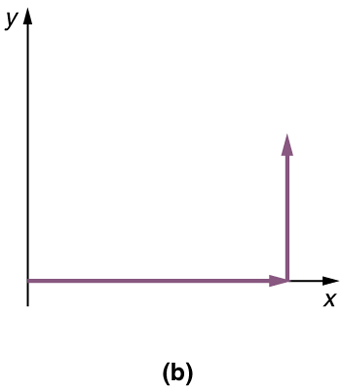

Step 2. Now draw an arrow to represent the second vector (5 blocks to the north). Place the tail of the second vector at the head of the first vector.

Step 3.If there are more than two vectors, continue this process for each vector to be added. Note that in our example, we have only two vectors, so we have finished placing arrows tip to tail.

Step 4.Draw an arrow from the tail of the first vector to the head of the last vector. This is the resultant, or the sum, of the other vectors.

Step 5. To get the magnitude of the resultant, measure its length with a ruler. (Note that in most calculations, we will use the Pythagorean theorem to determine this length.)

Step 6. To get the direction of the resultant, measure the angle it makes with the reference frame using a protractor. (Note that in most calculations, we will use trigonometric relationships to determine this angle.)

The graphical addition of vectors is limited in accuracy only by the precision with which the drawings can be made and the precision of the measuring tools. It is valid for any number of vectors.

Example: Adding Vectors Graphically Using the Head-to-Tail Method: A Woman Takes a Walk

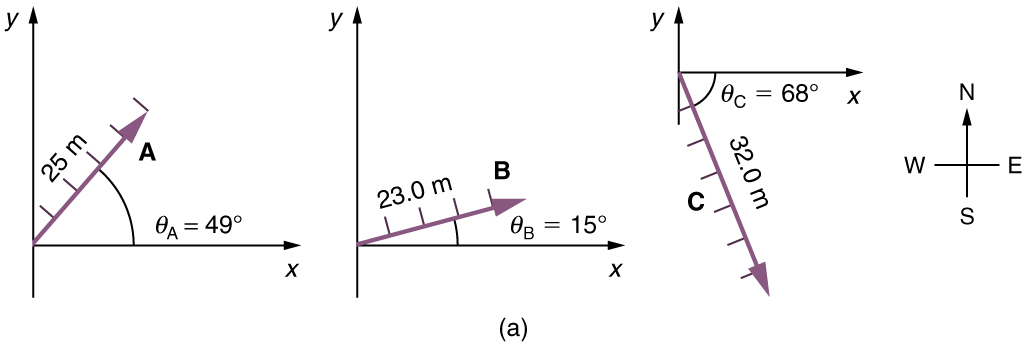

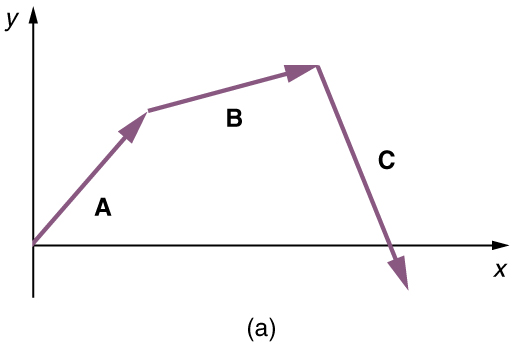

Use the graphical technique for adding vectors to find the total displacement of a person who walks the following three paths (displacements) on a flat field. First, she walks 25.0 m in a direction 49.0º north of east. Then, she walks 23.0 m heading text15.0º north of east. Finally, she turns and walks 32.0 m in a direction 68.0° south of east.

Strategy

Represent each displacement vector graphically with an arrow, labeling the first [latex]\vec{A}[/latex], the second [latex]\vec{B}[/latex], and the third [latex]\vec{C}[/latex], making the lengths proportional to the distance and the directions as specified relative to an east-west line. The head-to-tail method outlined above will give a way to determine the magnitude and direction of the resultant displacement, [latex]\vec{R}[/latex].

Solution

(1) Draw the three displacement vectors.

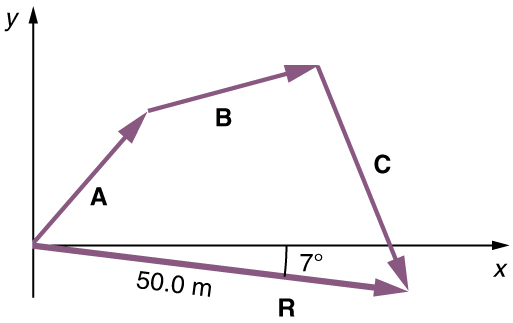

(2) Place the vectors head to tail retaining both their initial magnitude and direction.

(3) Draw the resultant vector, [latex]\text{R}[/latex].

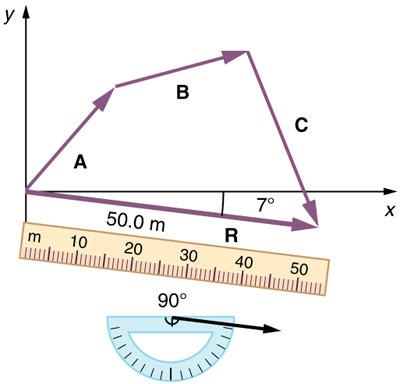

(4) Use a ruler to measure the magnitude of [latex]\vec{R}[/latex], and a protractor to measure the direction of [latex]\vec{R}[/latex]. While the direction of the vector can be specified in many ways, the easiest way is to measure the angle between the vector and the nearest horizontal or vertical axis. Since the resultant vector is south of the eastward pointing axis, we flip the protractor upside down and measure the angle between the eastward axis and the vector.

In this case, the total displacement [latex]\vec{R}[/latex] is seen to have a magnitude of 50.0 m and to lie in a direction 7.0º south of east. By using its magnitude and direction, this vector can be expressed as [latex]\vec{R} = \text{50.0m}[/latex] and [latex]\theta = /text{7.0º}[/latex] south of east.

Discussion

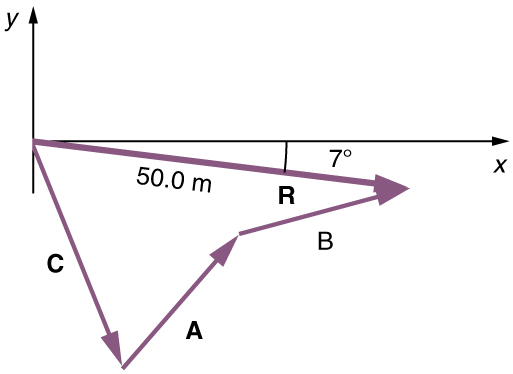

The head-to-tail graphical method of vector addition works for any number of vectors. It is also important to note that the resultant is independent of the order in which the vectors are added. Therefore, we could add the vectors in any order as illustrated in (Figure) and we will still get the same solution.

Here, we see that when the same vectors are added in a different order, the result is the same. This characteristic is true in every case and is an important characteristic of vectors. Vector addition is commutative. Vectors can be added in any order.

[latex]\vec{A} + \vec{B} = \vec{B} + \vec{A}[/latex]

(This is true for the addition of ordinary numbers as well—you get the same result whether you add [latex]2 + 3[/latex] or [latex]3 + 2[/latex], for example).

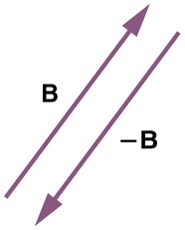

Vector Subtraction

Vector subtraction is a straightforward extension of vector addition. To define subtraction (say we want to subtract [latex]\vec{B}[/latex] from [latex]\vec{A}[/latex], written [latex]\vec{A} - \vec{B}[/latex], we must first define what we mean by subtraction. The negative of a vector [latex]\vec{B}[/latex] is defined to be [latex]-\vec{B}[/latex]; that is, graphically the negative of any vector has the same magnitude but the opposite direction, as shown in Figure 3.19. In other words, [latex]\vec{B}[/latex] has the same length as [latex]-\vec{B}[/latex], but points in the opposite direction. Essentially, we just flip the vector so it points in the opposite direction.

The subtraction of vector [latex]\vec{B}[/latex] from vector [latex]\vec{A}[/latex] is then simply defined to be the addition of [latex]-\vec{B}[/latex] to [latex]\vec{A}[/latex]. Note that vector subtraction is the addition of a negative vector. The order of subtraction does not affect the results.

[latex]\vec{A} - \vec{B} = \vec{A} + \left(-\vec{B}\right)[/latex]

This is analogous to the subtraction of scalars (where, for example, [latex]5 - 2 = 5 + \left(-2\right)[/latex]. Again, the result is independent of the order in which the subtraction is made. When vectors are subtracted graphically, the techniques outlined above are used, as the following example illustrates.

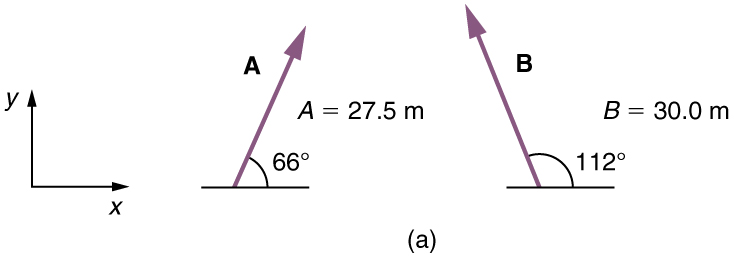

Example: Subtracting Vectors Graphically: A Woman Sailing a Boat

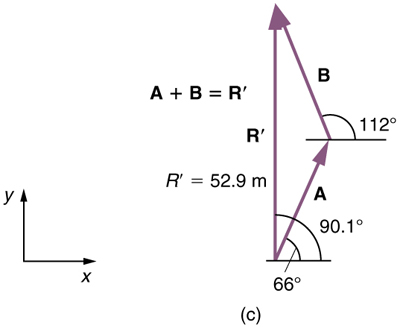

A woman sailing a boat at night is following directions to a dock. The instructions read to first sail 27.5 m in a direction 66.0º north of east from her current location, and then travel 30.0 m in a direction 112º north of east (or 22.0º west of north). If the woman makes a mistake and travels in the opposite direction for the second leg of the trip, where will she end up? Compare this location with the location of the dock.

Strategy

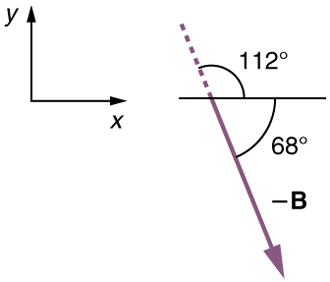

We can represent the first leg of the trip with a vector [latex]\vec{A}[/latex], and the second leg of the trip with a vector [latex]\vec{B}[/latex]. The dock is located at a location [latex]\vec{A} + \vec{B}[/latex]. If the woman mistakenly travels in the opposite direction for the second leg of the journey, she will travel a distance [latex]\textit{30.0m}[/latex] in the direction (180º–112º=68º) south of east. We represent this as [latex]-\vec{B}[/latex], as shown below. The vector [latex]-vec{B}[/latex] has the same magnitude as [latex]\vec{B}[/latex] but is in the opposite direction. Thus, she will end up at a location [latex]\vec{A} + \left(-vec{B}\right)[/latex], or [latex]\vec{A} - \vec{B}[/latex].

We will perform vector addition to compare the location of the dock, [latex]\vec{A} + \vec{B}[/latex], with the location at which the woman mistakenly arrives, [latex]\vec{A} + \left(-\vec{B}\right)[/latex].

Solution

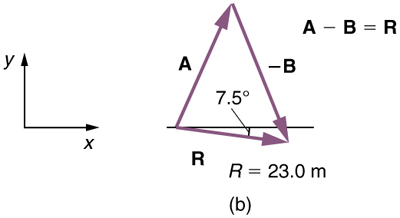

(1) To determine the location at which the woman arrives by accident, draw vectors [latex]\vec{A}[/latex] and [latex]-\vec{B}[/latex].

(2) Place the vectors head to tail.

(3) Draw the resultant vector [latex]\vec{R}[/latex].

(4) Use a ruler and protractor to measure the magnitude and direction of [latex]vec{R}[/latex].

In this case, [latex]\textit{R} = \text{23.0m}[/latex] and [latex]\theta = 5º[/latex] south of east.

(5) To determine the location of the dock, we repeat this method to add vectors [latex]\vec{A}[/latex] and [latex]\vec{B}[/latex]. We obtain the resultant vector [latex]\vec{R}[/latex]:

In this case [latex]\textit{R} = \text{52.9m}[/latex] and [latex]\theta = 90.1º[/latex] north of east.

We can see that the woman will end up a significant distance from the dock if she travels in the opposite direction for the second leg of the trip.

Discussion

Because subtraction of a vector is the same as addition of a vector with the opposite direction, the graphical method of subtracting vectors works the same as for addition.

Multiplication of Vectors and Scalars

If we decided to walk three times as far on the first leg of the trip considered in the preceding example, then we would walk [latex]3 \times 27.5[/latex], or [latex]\text{82.5m}[/latex], in a direction 66.0º north of east. This is an example of multiplying a vector by a positive scalar. Notice that the magnitude changes, but the direction stays the same.

If the scalar is negative, then multiplying a vector by it changes the vector’s magnitude and gives the new vector the opposite direction. For example, if you multiply by –2, the magnitude doubles but the direction changes. We can summarize these rules in the following way: When vector [latex]\vec{A}[/latex] is multiplied by a scalar [latex]c[/latex],

- the magnitude of the vector becomes the absolute value of [latex]c\vec{A}[/latex],

- if [latex]c[/latex] is positive, the direction of the vector does not change,

- if [latex]c[/latex] is negative, the direction is reversed.

In our case, [latex]c = 3[/latex] and [latex]\vec{A} = \text{27.5m}[/latex]. Vectors are multiplied by scalars in many situations. Note that division is the inverse of multiplication. For example, dividing by 2 is the same as multiplying by the value (1/2). The rules for multiplication of vectors by scalars are the same for division; simply treat the divisor as a scalar between 0 and 1.

Resolving a Vector into Components

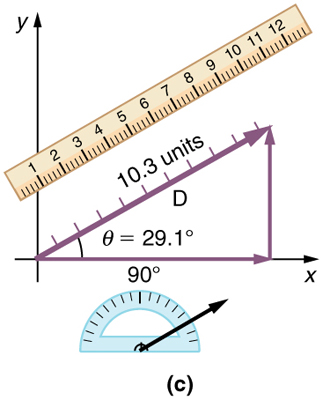

In the examples above, we have been adding vectors to determine the resultant vector. In many cases, however, we will need to do the opposite. We will need to take a single vector and find what other vectors added together produce it. In most cases, this involves determining the perpendicular components of a single vector, for example the x- and y-components, or the north-south and east-west components.

For example, we may know that the total displacement of a person walking in a city is 10.3 blocks in a direction 29.0º north of east and want to find out how many blocks east and north had to be walked. This method is called finding the components (or parts) of the displacement in the east and north directions, and it is the inverse of the process followed to find the total displacement. It is one example of finding the components of a vector. There are many applications in biomechanics where this is a useful thing to do. We will see this soon in Projectile Motion, and much more in the chapters on kinetics. Most of these involve finding components along perpendicular axes (such as north and east), so that right triangles are involved. The analytical techniques presented in the next section are ideal for finding vector components.

PhET Explorations: Maze Game

Learn about position, velocity, and acceleration in the "Arena of Pain". Use the green arrow to move the ball. Add more walls to the arena to make the game more difficult. Try to make a goal as fast as you can.

https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulations/maze-game