Chapter 2: Describing Movement in One Dimension, 1-D Linear Kinematics

2.4 Acceleration

Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

Adapted by: Rob Pryce, Alix Blacklin

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and distinguish between instantaneous and average acceleration.

- Understand the effect of accelerations in different directions.

- Calculate acceleration given initial time, initial velocity, final time, and final velocity.

In everyday conversation, to accelerate means to speed up. The accelerator in a car can in fact cause it to speed up. The greater the acceleration, the greater the change in velocity over a given time. Acceleration is defined as the rate of change of velocity.

Average acceleration can be calculated as:

[latex]\bar{a} = \frac {\Delta v}{\Delta t} = \frac {v_f-v_i}{t_f-t_i}[/latex]

where

[latex]\bar{a}[/latex] is average acceleration,

[latex]v[/latex] is velocity, and

[latex]t[/latex] is time.

(The bar over the a means 'average' acceleration)

Because acceleration is velocity in m/s divided by time in s, the SI units for acceleration are [latex]m/s^2[/latex], meters per second squared, or meters per second per second (m/s/s), which literally means by how many meters per second the velocity changes every second.

Recall that velocity is a vector—it has both magnitude and direction. This means that a change in velocity can be a change in magnitude (or speed), but it can also be a change in direction. For example, if a car turns a corner at constant speed, it is accelerating because its direction is changing. The quicker you turn, the greater the acceleration. So there is an acceleration when velocity changes either in magnitude (an increase or decrease in speed) or in direction, or both.

ACCELERATION AS A VECTOR

Acceleration is a vector in the same direction as the change in velocity, [latex]\Delta v[/latex]. Since velocity is a vector, it can change either in magnitude or in direction. Acceleration is therefore a change in either speed or direction, or both.

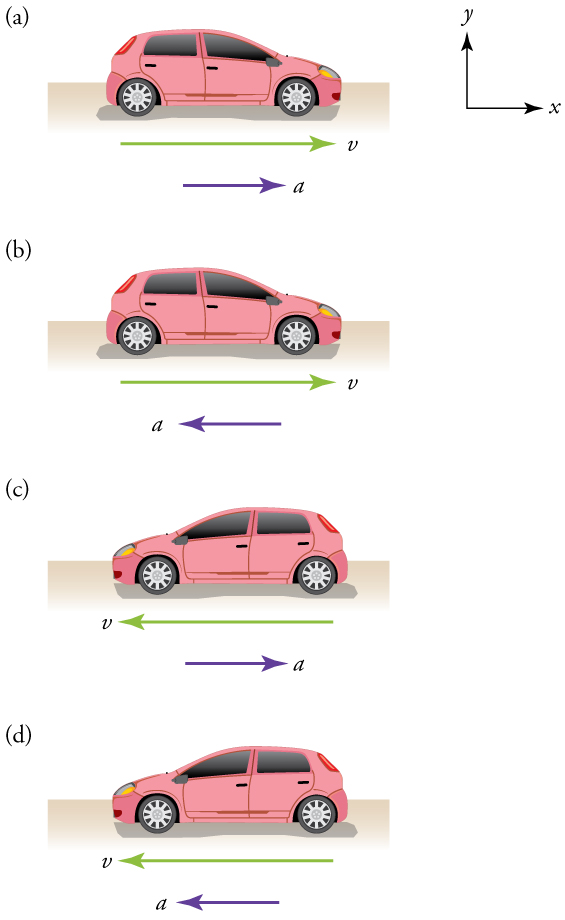

Keep in mind that although acceleration is in the direction of the change in velocity, it is not always in the direction of motion. When an object slows down, its acceleration is opposite to the direction of its motion. This is also known as deceleration.

MISCONCEPTION ALERT: DECELERATION vs. NEGATIVE ACCELERATION

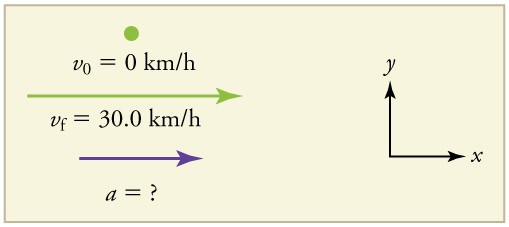

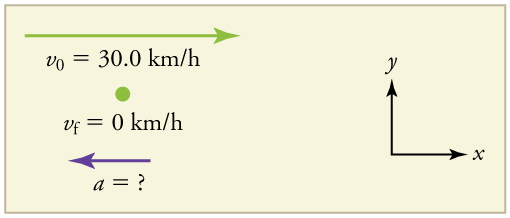

Deceleration always refers to acceleration in the direction opposite to the direction of the velocity. Deceleration always reduces speed. Negative acceleration, however, is acceleration in the negative direction in the chosen coordinate system. Negative acceleration may or may not be deceleration, and deceleration may or may not be considered negative acceleration. For example, consider Figure 2.14. Read the caption for an explanation of how the direction of the acceleration relates to the direction of motion.

Example: Calculating Acceleration: A Cyclist Starts the Race

A cyclist coming out of the gate to start a race accelerates from rest to a velocity of 12.50 m/s due west in 3.50 s. What is their average acceleration?

Strategy

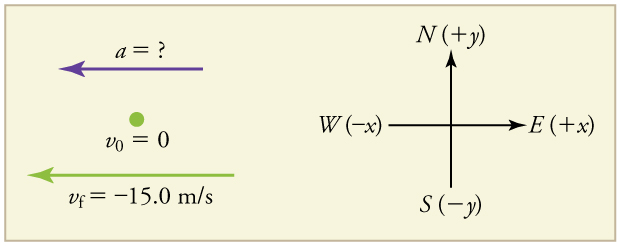

First we draw a sketch and assign a coordinate system to the problem. This is a simple problem, but it always helps to visualize it. Notice that we assign east as positive and west as negative. Thus, in this case, we have negative velocity.

We can solve this problem by identifying [latex]\Delta v[/latex] and [latex]\Delta t[/latex] from the given information and then calculating the average acceleration directly from the equation [latex]\bar{a} = \frac {\Delta v}{\Delta t} = \frac {v_f-v_i}{t_f-t_i}[/latex].

Solution

1. Identify the knowns. [latex]v_i = 0, v_f = -12.50 m/s[/latex] (the negative sign indicates direction toward the west), [latex]\Delta t = 3.50s[/latex].

2. Find the change in velocity. Since the rider is going from zero to -12.50 m/s, its change in velocity equals its final velocity: [latex]\Delta v = v_f = -12.50 m/s[/latex].

3. Plug in the known values ([latex]\Delta v[/latex] and [latex]\Delta t[/latex]) and solve for the unknown [latex]\bar{a}[/latex].

[latex]\bar{a} = \frac {\Delta v} {\Delta t} = \frac {-12.50m/s} {3.50s} = -3.57 m/s^2[/latex]

Discussion

The negative sign for acceleration indicates that acceleration is toward the west. An acceleration of 3.57 [latex]m/s^2[/latex] due west means that the rider increases its velocity by 3.57 m/s due west each second, that is, 3.57 meters per second per second, which we write as 3.57 [latex]m/s^2[/latex]. This is truly an average acceleration, because the start is probably not smooth. Later we will learn how to estimate the force required to produce that acceleration.

Instantaneous Acceleration

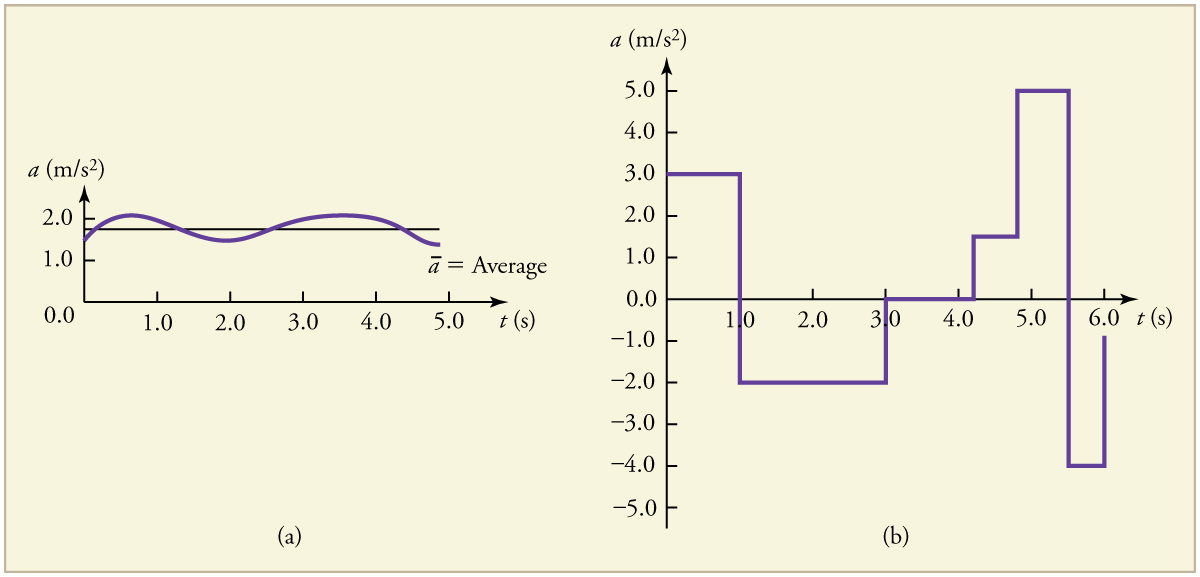

Instantaneous acceleration [latex]a[/latex], or the acceleration at a specific instant in time, is obtained by the same process as discussed for instantaneous velocity in the previous section—that is, by considering an infinitesimally small interval of time. How do we find instantaneous acceleration using only algebra? One answer is that we choose an average acceleration that is representative of the motion. Figure 2.17 shows graphs of instantaneous acceleration versus time for two very different motions. In (a), the acceleration varies slightly and the average over the entire interval is nearly the same as the instantaneous acceleration at any time. In this case, it would be reasonable to treat this motion as if it had a constant acceleration equal to the average (in this case about [latex]1.8 m/s^2[/latex]). In (b), the acceleration varies drastically over time. In these situations it is better to consider smaller time intervals and examine the average acceleration for each interval. For example, we could consider motion over the time intervals from 0 to 1.0 s and from 1.0 to 3.0 s as separate motions with accelerations of [latex]+3.0 m/s^2[/latex] and [latex]-2.0 m/s^2[/latex], respectively.

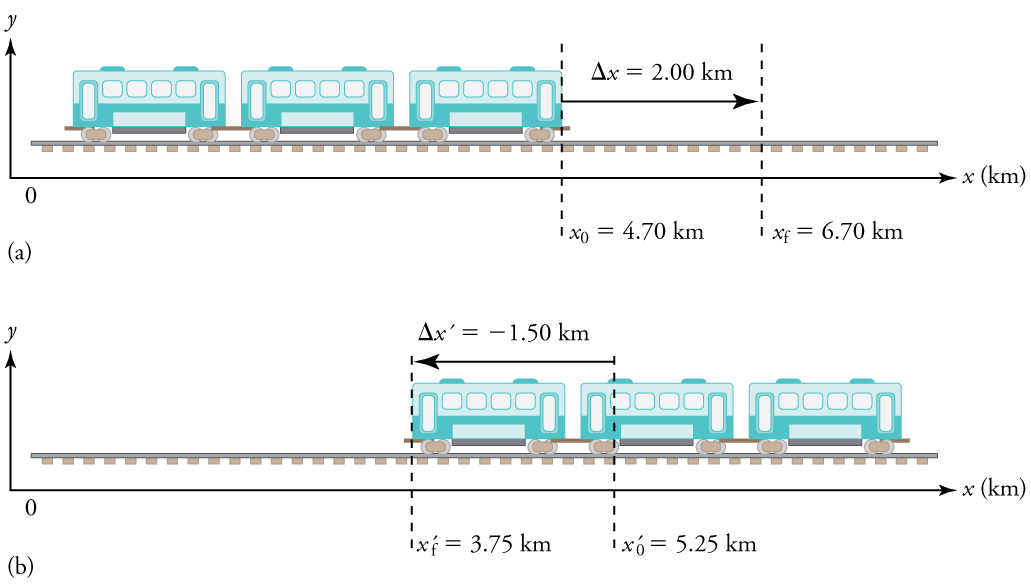

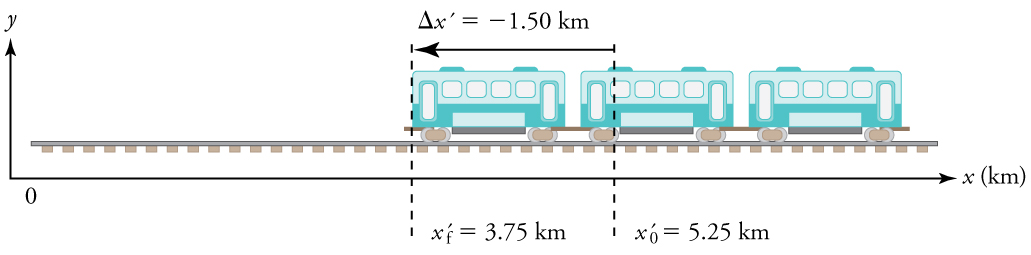

The next several examples consider the motion of the subway train shown in Figure 2.18. In (a) the train moves to the right, and in (b) it moves to the left. The examples are designed to further illustrate aspects of motion and some of the reasoning that goes into solving problems.

Example: Calculating Displacement: A Subway Train

What are the magnitude and sign of displacements for the motions of the subway train shown in parts (a) and (b) of Figure 2.18?

Strategy

A drawing with a coordinate system is already provided, so we don’t need to make a sketch, but we should analyze it to make sure we understand what it is showing. Pay particular attention to the coordinate system. To find displacement, we use the equation [latex]\Delta x = x_f - x_i[/latex]. This is straightforward since the initial and final positions are given.

Solution

1. Identify the knowns. In the figure we see that for part a):

[latex]x_f = 6.70 km[/latex] and [latex]x_i = 4.70 km[/latex],

and for part b):

[latex]{x\prime}_f = 3.75 km[/latex] and [latex]{x\prime}_i = 5.25 km[/latex].

2. Solve for displacement in part (a).

3. Solve for displacement in part (b).

Discussion

The direction of the motion in (a) is to the right and therefore its displacement has a positive sign, whereas motion in (b) is to the left and thus has a negative sign.

Example: Comparing Distance Traveled with Displacement: A Subway Train

What are the distances traveled for the motions shown in parts (a) and (b) of the subway train in Figure 2.18?

Strategy

To answer this question, think about the definitions of distance and distance traveled, and how they are related to displacement. Distance between two positions is defined to be the magnitude of displacement, which was found in Example 2.2. Distance traveled is the total length of the path traveled between the two positions. In the case of the subway train shown in Figure 2.18, the distance traveled is the same as the distance between the initial and final positions of the train.

Solution

1. The displacement for part (a) was +2.00 km. Therefore, the distance between the initial and final positions was 2.00 km, and the distance traveled was 2.00 km.

2. The displacement for part (b) was -1.50 km. Therefore, the distance between the initial and final positions was 1.50 km, and the distance traveled was 1.50 km.

Discussion

Distance is a scalar. It has magnitude but no sign to indicate direction.

Example: Calculating Acceleration: A Subway Train Speeding Up

Suppose the train in 2.18 (a) accelerates from rest to 30.0 km/h in the first 20.0 s of its motion. What is its average acceleration during that time interval?

Strategy

It is worth it at this point to make a simple sketch:

This problem involves three steps. First we must determine the change in velocity, then we must determine the change in time, and finally we use these values to calculate the acceleration.

Solution

1. Identify the knowns:

[latex]{v}_{i}=0[/latex] (the trains starts at rest),

[latex]{v}_{f}=\text{30}\text{.}\text{0 km/h}[/latex], and

[latex]\Delta t=\text{20}\text{.}\text{0 s}[/latex].

2. Calculate [latex]\Delta v[/latex]. Since the train starts from rest, its change in velocity is [latex]\Delta v\text{=}\phantom{\rule{0.20em}{0ex}}\text{+}\text{30.0 km/h}[/latex], where the plus sign means velocity to the right.

3. Plug in known values and solve for the unknown, [latex]\bar{a}[/latex].

4. Since the units are mixed (we have both hours and seconds for time), we need to convert everything into SI units of meters and seconds. (See Physical Quantities and Units for more guidance.)

Discussion

The plus sign means that acceleration is to the right. This is reasonable because the train starts from rest and ends up with a velocity to the right (also positive). So acceleration is in the same direction as the change in velocity, as is always the case.

Example: Calculate Acceleration: A Subway Train Slowing Down

Now suppose that at the end of its trip, the train in Figure 2.18(a) slows to a stop from a speed of 30.0 km/h in 8.00 s. What is its average acceleration while stopping?

Strategy

In this case, the train is decelerating and its acceleration is negative because it is toward the left. As in the previous example, we must find the change in velocity and the change in time and then solve for acceleration.

Solution

1. Identify the knowns.

[latex]v_i=\text{30}\text{.0 km/h}[/latex],

[latex]v_f=0 km/h[/latex] (the train is stopped, so its velocity is 0), and

[latex]\Delta t=\text{8.00 s}[/latex].

2. Solve for the change in velocity, [latex]\Delta v[/latex].

3. Plug in the knowns, [latex]\Delta v[/latex] and [latex]\Delta t[/latex], and solve for [latex]\bar {a}[/latex].

4. Convert the units to meters and seconds.

Discussion

The minus sign indicates that acceleration is to the left. This sign is reasonable because the train initially has a positive velocity in this problem, and a negative acceleration would oppose the motion. Again, acceleration is in the same direction as the change in velocity, which is negative here. This acceleration can be called a deceleration because it has a direction opposite to the velocity.

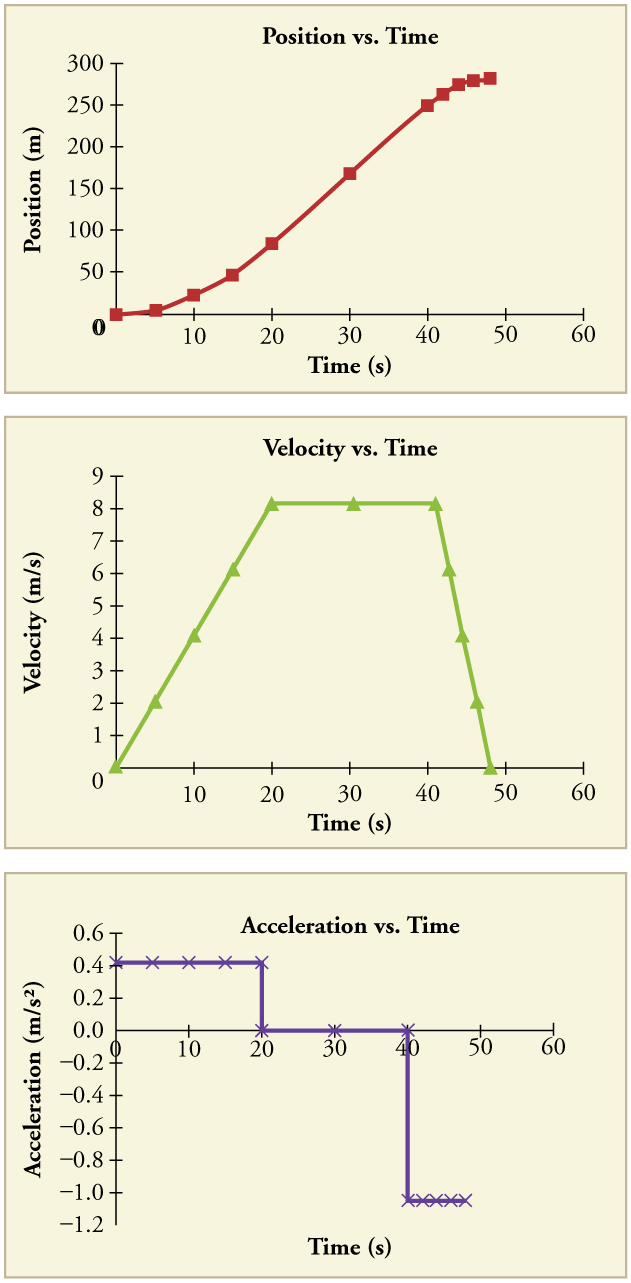

Graphing Position, Velocity, Acceleration

The graphs of position, velocity, and acceleration vs. time for the trains in Example 2.4 and Example 2.5 are displayed in Figure 2.21. (We have taken the velocity to remain constant from 20 to 40 s, after which the train decelerates.)

Example: Calculating Average Velocity: The Subway Train

What is the average velocity of the train in part b of Example 2.2, and shown again below, if it takes 5.00 min to make its trip?

Strategy

Average velocity is displacement divided by time. It will be negative here, since the train moves to the left and has a negative displacement.

Solution

1. Identify the knowns.

[latex]{x\prime }_{f}=3\text{.75 km}[/latex],

[latex]{x\prime }_i=\text{5.25 km}[/latex],

[latex]\Delta t=\text{5.00 min}[/latex].

2. Determine displacement, [latex]\Delta x\prime[/latex]. We found [latex]\Delta x\prime[/latex] to be [latex]-\text{1.5 km}[/latex] in Example 2.2.

3. Solve for average velocity.

4. Convert units.

Discussion

The negative velocity indicates motion to the left.

Example: Calculating Deceleration: The Subway Train

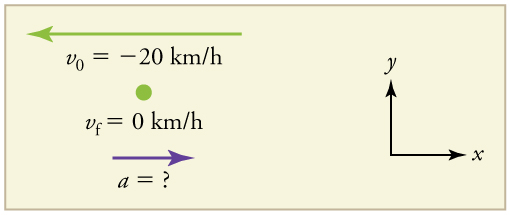

Strategy

Once again, let’s draw a sketch:

As before, we must find the change in velocity and the change in time to calculate average acceleration.

Solution

1. Identify the knowns:

[latex]{v}_{0}=-\text{20 km/h}[/latex],

[latex]{v}_{f}=0 km/h[/latex],

[latex]\Delta t=\text{10}\text{.}0 s[/latex].

2. Calculate [latex]\Delta v[/latex]. The change in velocity here is actually positive, since

[latex]\Delta v = v_f - v_i = 0 - \left(-\text{20 km/h} \right) = + \text{20km/h}[/latex]

3. Solve for [latex]\bar{a}[/latex].

[latex]\bar{a}=\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta t}=\frac{+\text{20.0 km/h}}{\text{10.0 s}}[/latex]

4. Convert units.

Discussion

The plus sign means that acceleration is to the right. This is reasonable because the train initially has a negative velocity (to the left) in this problem and a positive acceleration opposes the motion (and so it is to the right). Again, acceleration is in the same direction as the change in velocity, which is positive here. As in Example 2.5, this acceleration can be called a deceleration since it is in the direction opposite to the velocity.

Sign and Direction

Perhaps the most important thing to note about these examples is the signs of the answers. In our chosen coordinate system, plus means the quantity is to the right and minus means it is to the left. This is easy to imagine for displacement and velocity. But it is a little less obvious for acceleration. Most people interpret negative acceleration as the slowing of an object. This was not the case in Example 2.7, where a positive acceleration slowed a negative velocity. The crucial distinction was that the acceleration was in the opposite direction from the velocity. In fact, a negative acceleration will increase a negative velocity. For example, the train moving to the left in Figure 2.22 is sped up by an acceleration to the left. In that case, both [latex]v[/latex] and [latex]a[/latex] are negative. The plus and minus signs give the directions of the accelerations. If acceleration has the same sign as the velocity, the object is speeding up. If acceleration has the opposite sign as the velocity, the object is slowing down.

Check Your Understanding

An airplane lands on a runway traveling east. Describe its acceleration.

Solution

If we take east to be positive, then the airplane has negative acceleration, as it is accelerating toward the west. It is also decelerating: its acceleration is opposite in direction to its velocity.

PhET Explorations: Moving Man Simulation

Learn about position, velocity, and acceleration graphs. Move the little man back and forth with the mouse and plot his motion. Set the position, velocity, or acceleration and let the simulation move the man for you.