11. Hierarchical structure in words

11.1 Hierarchical structure in compound words

As we saw in the previous chapter, some languages, including English, have a productive process through which new words can be formed that involves putting two words together. The resulting words are called compounds.

| rice | pot | → | rice-pot |

|---|---|---|---|

| swan | boat | → | swan-boat |

| phone | case | → | phone-case |

This process is, theoretically, infinitely recursive, meaning that we can continue to make new words from existing words.

| rice-pot | rack | → | rice-pot-rack |

|---|---|---|---|

| swan-boat | jacket | → | swan-boat-jacket |

| phone-case | store | → | phone-case-store |

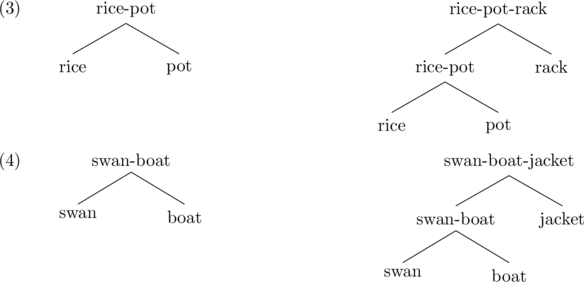

Rice-pot has two morphemes, rice and pot. When we put them together, we make something whose meaning is the combination of both. This idea is represented in terms of bracketing structure.

![]()

Inside each pair of brackets is one meaning “unit.” So rice-pot involves three pairs of brackets: one around rice, one around pot and one around the compound rice-pot. Same with swan-boat.

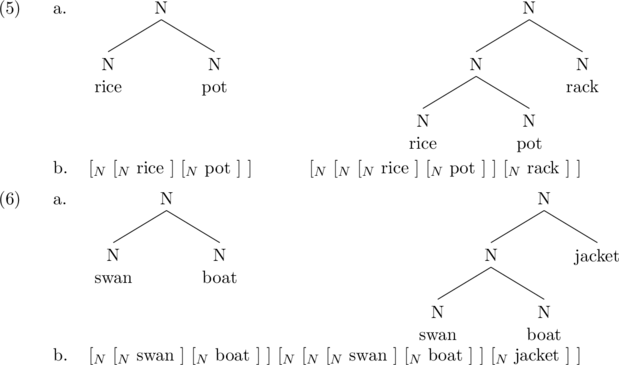

This way of representation allows us to iteratively represent more complex compounds, as in (2).

![]()

When we build larger compounds, we are creating a meaningful unit, and then adding to it. So first I create the word rice-pot, and it has a meaning like, “a pot for rice.” Then I create the word rice-pot-rack, which has the meaning “a rack for pots for rice.” In other words, the meaning of the entire word depends on the meaning of its parts.

Of course, the more complex our compounds become, the more difficult it is to read the bracketing structure. So another way to express the exact same information is by using a tree, as in (3) and (4).

Each node in the tree corresponds to one pair of brackets. Thus, trees and brackets provide the exact same amount of information, it’s just that trees do it in a visually more appealing way. But it’s always possible to state a bracketing structure as a tree, and vice versa.

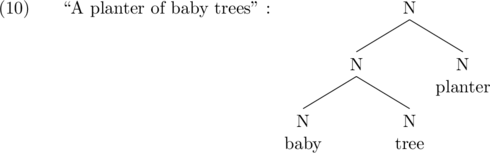

I can actually make my representations slightly more informative by adding in category information. The following trees and bracketing structures give us all the preceding information, and they additionally tell us what the category of each morpheme is.

Note that it’s not necessary to explicitly state the compound words that are formed at each junction, because I can just look lower in the tree to figure out what that word is. The reason it’s good to list the category, though, is that you can combine more than one category. We therefore want to know which category “projects,” that is, provides the part of speech to the resulting word.

Hierarchical structure

These tree and bracketed diagrams illustrate one property of language: words and sentences have hierarchical structure. A hierarchical structure is a way of organizing elements. You might encounter hierachical structure in a workplace, where, for example, a worker might report to their team leader, the team leader might report to a department head, and the department head might report to the CEO.

In morphology trees, though, instead of reporting to people higher up the chain of command, hierarchical structure represents containment relationships. The nodes higher up in the structure contain the nodes that branch off below them.

Structural ambiguity

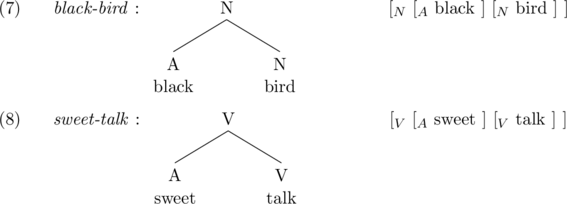

What does the following compound mean?

![]()

Many of you will say that it means, “someone who plants baby trees.” And many of you will say that it means “a tree-planter who is a baby.” Both of these are right; it’s possible to get both readings of the compound.

If we wanted to represent each meaning, we would choose different structures. The “baby-trees” meaning would have the following representations.

The reason is that we want “baby tree” to be a unit of meaning, i.e., a constituent, because that meaning describes the kind of planter it is.

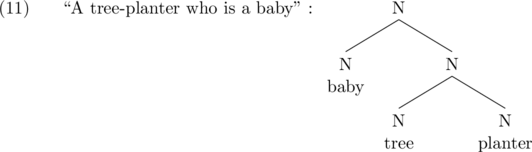

On the other hand, the “tree-planting-baby” meaning would have the following representation

The reason is that we want “tree-planter” to be a unit of meaning first, because ultimately we’re describing a kind of tree-planter.

This kind of ambiguity is called structural ambiguity, because we can represent the ambiguity structurally.

There is another kind of ambiguity called lexical ambiguity. The word bank is lexically ambiguous, because it means two different things (a financial institution and the side of a river). But it’s not structurally ambiguous because the two meanings do not correspond to different structures.

The take-away point here is that different meanings correspond to different structures. More abstractly, the different meanings are the result of packaging the information in different ways.

Check yourself!

References and further resources

Attribution

This section is adapted from the following CC BY NC SA source:

↪️ Gluckman, John. n.d. Chapter 3: Brackets and trees. The science of syntax. https://pressbooks.pub/syntax/chapter/brackets-and-trees

A word with two or more roots.

Iteratively applying a rule to its own output.

A representation using brackets to indicate constituents and categories in morphology or syntax.

Any point where multiple branches meet in a syntax tree, as well as the endpoint of any branch.

The organization of elements into ranks or levels, where each level contains or is in charge of the lower levels.

A group of words or morphemes that behave as a unit.

When a word or sentence can be associated with more than one hierarchical structure, each resulting in different possible meanings.

When a word or sentence is ambiguous because one of the morphemes has a homonym.