4. Linguistic data in morphosyntax

4.8. Becoming a linguist: Glossing signed language data

Signed language data is glossed quite a bit differently than spoken language data.

Describing the form of signs

In signed languages, the basic independent meaningful unit, the equivalent of a spoken language word, is generally an individual sign. Signs are typically articulated with the hands and arms, and so are called manual markers, from the Latin word for hand.

Manual markers

Manual markers are best described by breaking them down into four parameters: handshape, orientation, location, and movement. We will only briefly describe manual markers here.

Handshape

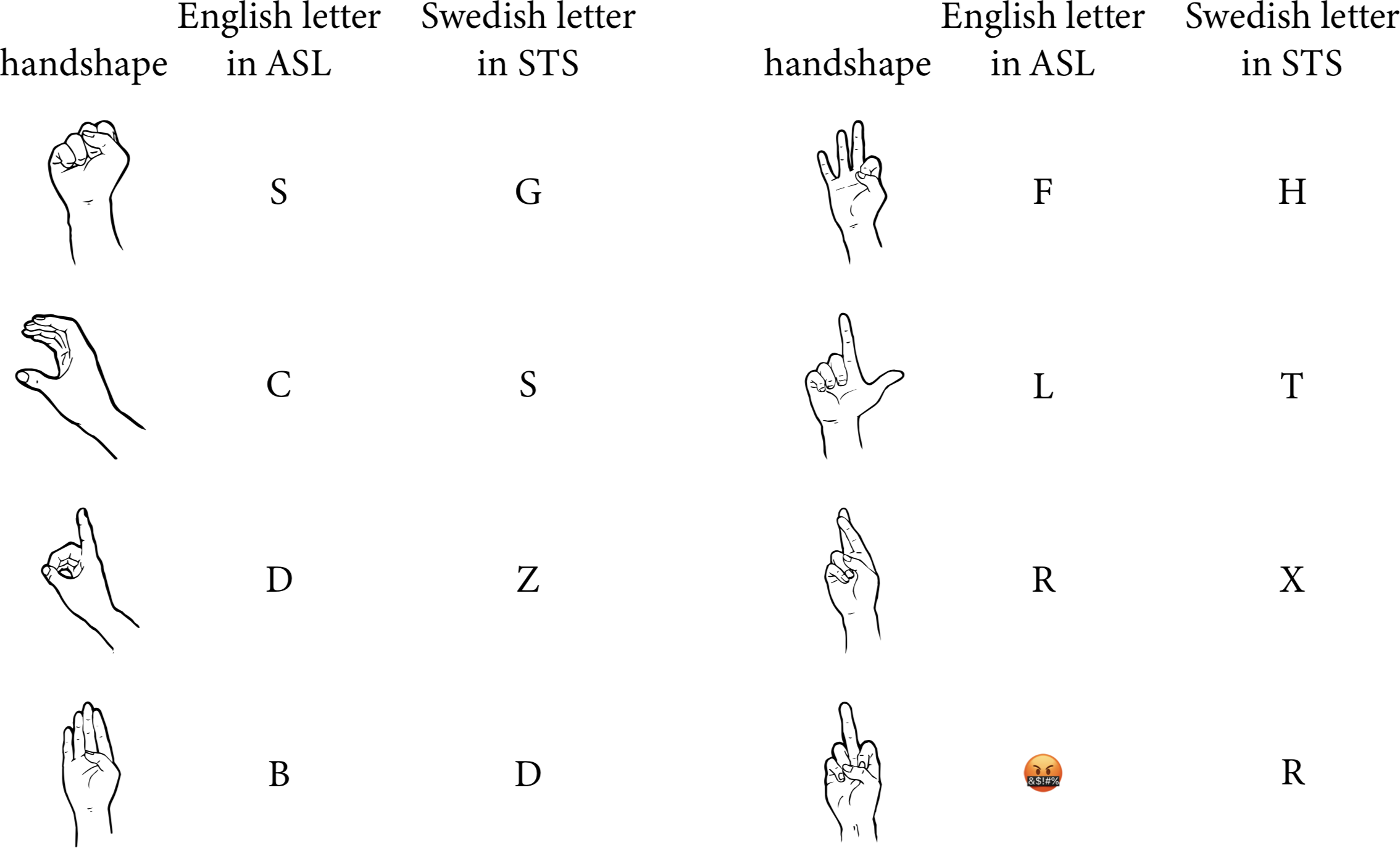

The handshape of a sign is how the fingers are configured. Handshape can be described in prose, by describing the locations of the different fingers, or by including an icon depicting the shape of the hand.

Since many handshapes are used to represent numbers or letters from the writing system of the ambient spoken language, a common shorthand for describing handshapes is to use numbers and letters. Thus, since the first handshape in Figure 1 is used to represent the the English letter <S> in ASL, so it can be called the “S handshape”. However, each signed language has different handshapes for different letters and numbers, as shown in Figure 1, and so this shorthand is ambiguous unless it is clear which signed language is being used.

Orientation

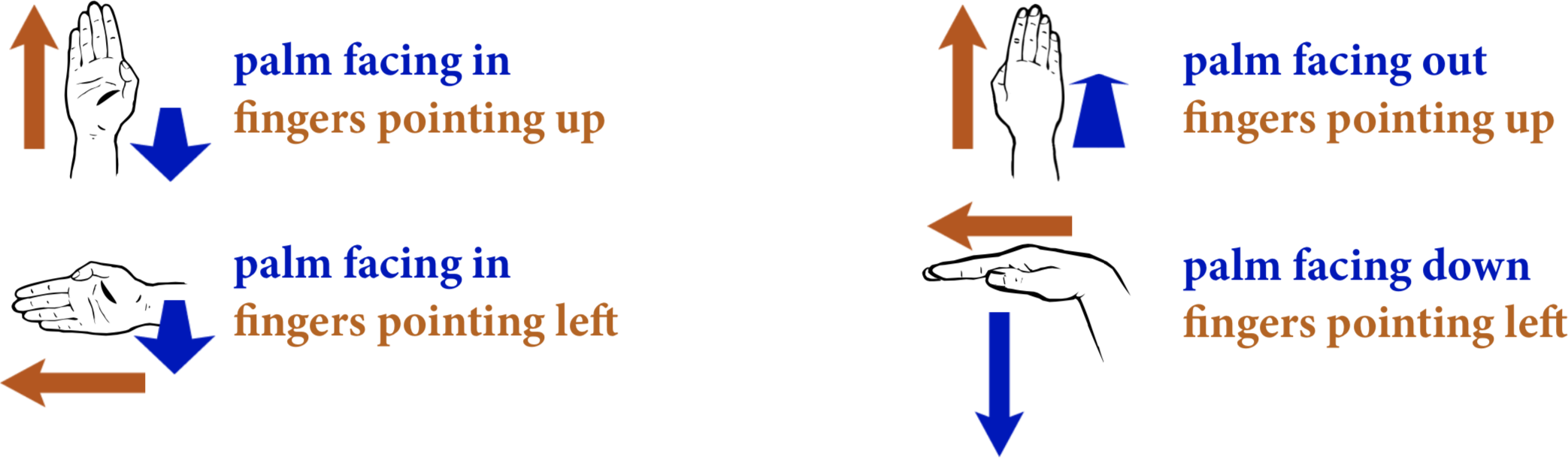

The hand, even while maintaining the same handshape, can be rotated, which is known as the orientation of the sign. The orientation of the hand is divided into two components: the palm orientation (which way the palm is facing, shown in blue in Figure 2) and the finger orientation (the direction the bones inside the hand are pointing, which is where the fingers would point when straightened, shown in orange in Figure 2).

Note that if the fingers are bent, the finger orientation may be a bit confusing, but you can determine orientation by straightening out the fingers to see where the fingertips point. For example, in Figure 3, the A handshape is shown. The palm orientation is facing the camera. The finger orientation is not downwards, but upwards because if the fingers were straightened, they would be pointing upwards. In other words, the knuckles are pointing upwards.

Location

The location of a sign is where in space or on the body it is articulated. Signs can be articulated in a variety of locations. The default location is neutral signing space, the area just in front of the signer’s torso, but locations can be nearly anywhere on the body. They tend to be around some specific part of the head, but other body parts are also possible locations.

Movement

All signs have a handshape, an orientation, and a location, and many signs also have movement, which is divided into two types: path and local movement. Path movement involves articulation at the elbow and/or shoulder and moves the sign from one location in the signing space to another. Local movement involves articulation below the elbow and changes the sign’s handshape and/or orientation.

Non-manual markers

Signed languages do not only involve movement of the hands and arms. The rest of the body, especially the torso and the parts of the face, are also involved and are known as the non-manual markers. Non-manual markers may continue longer than a single sign, sometimes marking an entire phrase.

Some examples of movements involved in non-manual markings include eye gaze changes, eyelid narrowing and opening, eyebrow raising and lowering, torso leaning and rotation, head tilting and rotation, cheek puffing, lip rounding and spreading, teeth baring, and more. Nearly any other body part can be a non-manual articulator, even the feet and buttocks in some signed languages, such as Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana (Nyst 2007) and Kata Kolok in Indonesia (Marsaja 2008).

Encoding the form of signs

There is no commonly accepted transcription system for describing the form of signs. Several notation systems for signed languages have been constructed (see Hochgesang 2014 for an overview), but no single consistent standard has emerged, and the systems that do exist can be difficult to work with.

In morphology and syntax, the form of a sign is not always relevant, so it may not be described at all. Instead, the sign is translated into a word in the ambient spoken language and is referred to by that word, which is typically written in all caps.

When the form of a sign is relevant, typically texts will include videos, diagrams, and/or pictures of the sign, as well as describing the sign in words. If there is movement in the sign and video cannot be used, a series of pictures or superimposed arrows are used to indicate the movement.

Two-line signed language glosses

Signed languages are typically glossed with two-line glosses, which correspond to the second and third line of three-line spoken language glosses. A line providing the form of the signed language data is not included, due to the lack of a convention for transcribing signed languages. However, pictures, diagrams, or a video are often included in addition to the two-line gloss. The final line in the gloss provides a natural translation into the meta language, just as with spoken languages.

In signed language glosses, all signs are glossed in all caps, both lexical and functional, unlike spoken language glosses, where only the functional words are in all caps. This is illustrated in (1), where the possessive marker, POSS, as well as the lexical signs BROTHER, OFTEN, and TRAVEL, are all in caps. Sources will vary as to whether small caps or regular caps are used.

| (1) | German Sign Language (DGS) |

| POSS1 BROTHER OFTEN TRAVEL | |

| ‘My brother often travels.’ |

(Baker et al. 2016: 95)

Indices

Signed languages tend to use space to track reference through indices (singular: index). An index is a spot in the signing space that is assigned to a particular referent. For first and second person reference, signers will point at themself or at the addressee. For third person reference, signers may point directly at the referent (called absolute reference) or at an arbitrary spot in the signing space that they have assigned to that referent by describing the referent and then pointing at that location.

Indices are usually indicated with the word INDEX or the abbreviation IX, followed by a subscript that indicates which referent is meant. For example, in (2), the signer signs the word for Ottawa and then points in the location of Ottawa

| (2) | Inuit Sign Language (IUR) |

| OTTAWA INDEX-LOCOttawa CALL-ON-PHONE LONG AGO | |

| ‘Long ago, I phoned Ottawa.’ (referring to a shop in Ottawa) |

(Schuit et al. 2011: 21)

For first, second, and arbitrary third person references, a subscript number is used to gloss distinct index locations, as shown in (3).

| (3) | Inuit Sign Language (IUR) |

| USE-ICE-AUGER1 INDEX3a USE-ICE-AUGER3a INDEX3a | |

| ‘I use an ice auger, and so does he.’ |

(Schuit et el. 2011: 22)

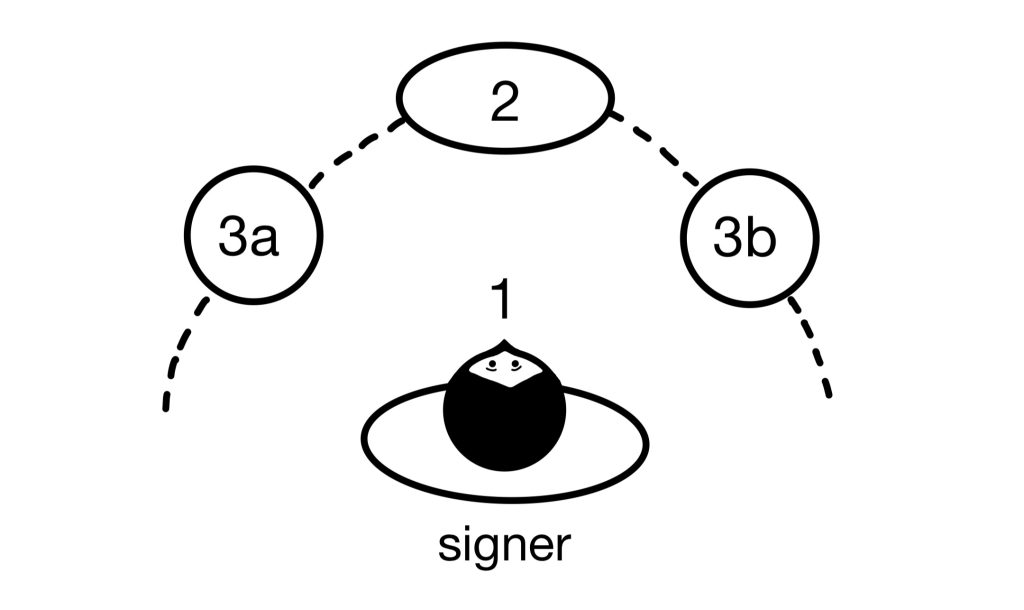

The meanings of the different numbers that are used with indices are schematized in Figure 4. A ‘1’ indicates that the index is pointed at the signer, a ‘2’ that the index is pointed at the addressee, and a ‘3’ that the index is pointed at some other location. Since more than one third person referent may be used in the same conversation, the third person referents are also marked with a letter to keep track of the distinct third person referents.

Verbs are sometimes signed moving from one index location to another, which is often analyzed as subject and object agreement. These are glossed with a subscript number at the beginning of the sign to indicate its starting location and a subscript number at the end of the sign to indicate its endpoint position. For example, in (4), the verb FORCE is signed moving from the signer to the addressee, while the sign GIVE is signed moving from the addressee towards the signer.

| (4) | American Sign Language (ASL) |

| 1INDEX 1FORCE2 2GIVE1 MONEY | |

| ‘I’ll force you to give me the money.’ |

(Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006: 36)

Classifiers

Another common morphosyntactic marker used in signed languages which requires special mention are the classifiers. Classifiers in signed languages are used to describe objects and actions as part of depicting signs. Depicting signs take advantage of the visual-spatial medium of signed languages to vibrantly describe situations through schematic representations. Particular handshapes are used to indicate different types of objects and entities, and they are placed and moved throughout the signing space in an iconic manner to depict their relative placement and/or their movement through space.

You can watch this video to see some examples of classifiers and depicting signs being used and described.

In depicting signs, different handshapes are used as classifier signs for different kinds of objects or different aspects of the same object. Each of these handshapes is not specific to the depicting sign or to a specific object. Instead, a particular classifier handshape is used for a whole class of objects. These depicting signs may indicate the whole entity and how it moves through space, how people hold or handle the entity, a particular body part of the entity, or the size and shape of the entity.

Classifiers are typically indicated in glosses with the abbreviation CL, followed by a colon and some indication of the handshape. The handshape may be indicated with a small image of the handshape (5a), with the name of the handshape according to a particular signed language alphabet (5b), by the name of the object (5c), or by a description of the class of objects (5d).

| (5) | American Sign Language (ASL) | |

| a. | TWO-DAYS-AGO INDEX2 s-u-e IX3a FLOWER 2GIVE-CL:👌3a | |

| ‘Did you give Sue a flower two days ago?’ | ||

| (5) | b. | TWO-DAYS-AGO INDEX2 s-u-e IX3a FLOWER 2GIVE-CL:F3a |

| ‘Did you give Sue a flower two days ago?’ |

| (5) | c. | TWO-DAYS-AGO INDEX2 s-u-e IX3a FLOWER 2GIVE-CL:FLOWER3a |

| ‘Did you give Sue a flower two days ago?’ |

| (5) | d. | TWO-DAYS-AGO INDEX2 s-u-e IX3a FLOWER 2GIVE-CL:LONG-THIN-OBJECT3a |

| ‘Did you give Sue a flower two days ago?’ |

(Baker et al. 2016: 338)

Since depicting signs make use of space and iconic movements, they are difficult to gloss. Instead, they are often shown through images and video.

Other symbols

Many other symbols are common in signed language glosses. Some are listed in the table below.

| Symbol | Description | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| SIGN++ | two following plus symbols | Indicates that the sign is repeated in a morphological process called reduplication. |

| SIGN – – – – – | five following hyphens | Indicates that part of a sign is held in place while the other hand continues signing. |

| SIGN^SIGN | two signs joined by a caret | Indicates the formation of a compound sign. |

| SIGN-SIGN | two signs joined by a hyphen | Indicates that multiple words in the meta language are required to translate a single sign in the object language. |

| s-i-g-n | lower case letters joined by hyphens | Indicates a fingerspelled word. |

| “xxx” | lower case letters enclosed in quotation marks | Indicates a gesture. |

Glossing non-manual markers

Since non-manual markers occur simultaneously to the manual markers and might last for several signs, they are usually indicated above the gloss with a line to indicate how long the non-manual marker is articulated. At the end of the line, an abbreviation is included to indicate which non-manual marker was used. These might indicate the gesture itself, such as hn for ‘head nod’ which indicates affirmation or an imperative sentence, or the meaning of the gesture, such as y/n for yes-no questions, which is often indicated by raising the eyebrows.

Some examples of non-manual markers are shown below in (6), where a backward head tilt, a marker of negation in some Eastern Mediterranean signed languages, is indicated with the abbreviation bht. Note that the length of the line matters! In (6a), only the sign HURRY is negated with a backward head tilt. The first part of the sentence, about going to work, is not negated. In (6b), on the other hand, the whole sentence is negated. The length of the line, then, can change the meaning of the sentence.

| (6) | Greek Sign Language | |||

| Non-manual signal “bht” (body-hand-tier) applies to HURRY. | ||||

| bht | ||||

| a. | WORK AFTER GO, | HURRY. | ||

| ‘Don’t be in a hurry, we will go (there) after work.’ | ||||

| The non-manual signal “bht” (body-hand-tier) applies from INDEX through GO NOT. | ||||

| bht | ||||

| b. | INDEX1 AGAIN GO NOT. | |||

| ‘I won’t go (there) again.’ | ||||

(Baker et al. 2016: 139)

Multiple non-manual markers may be articulated simultaneously, in which case they may be stacked on top of each other, as shown below in (7). In this example, the eyebrows are raised for the entire sentence, indicated by re, while the head nod, indicated by hn, extends only over the final two signs.

| (7) | French Sign Language | ||

| The non-manual signal ‘hn’ (head nod) applies from INDEX through BITE! | |||

| hn | |||

| The non-manual signal ‘re’ (raised eyebrows) applies from PLEASE through BITE! | |||

| re | |||

| PLEASE | INDEX2 | BITE! | |

| ‘Please, bite it!’ | |||

(Baker et al. 2016: 135)

Some common abbreviations for non-manual markers in ASL are listed below in Table 2. Note that pairings between gestures and meanings are likely to vary from language to language, and even within ASL. The gesture and meaning pairs described below are some of the more common ones used in ASL.

| Abbreviation | Gesture | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| aff | repeated head nods | affirmation |

| bl | body lean in a particular direction | |

| hn | a single head nod | affirmation or imperative marker |

| neg | headshake and negative facial expression | negation |

| re | raised eyebrows | marks subordinate clauses |

| t | raised eyebrows and forward tilt of the head | topicalized constituent |

| wh | lowered eyebrows | content (wh-) question |

| y/n | raised eyebrows and head forward | yes-no question |

| /xxx/ | various mouth gestures | |

| )( | sucked in cheeks | ‘small’ |

| () | blown out cheets | ‘big’ |

Key takeaways

- The form of manual signs in signed languages can be described by breaking them down into four parameters: handshape, orientation, location, and movement. There is no commonly accepted transcription system for the form of signs; instead they are typically described in words and/or are depicted through image or video.

- Signed languages are typically glossed with a two-line gloss. The first line indicates a sign-by-sign translation while the second line includes a natural translation into the meta language. Both lexical and functional signs are in all caps.

- Indices, which indicate a location in the signing space or in the world, are indicated with subscripts.

- Non-manual markers include facial expressions and body postures. They might last longer than a single sign and are typically indicated by a line extended over the gloss, indicating which signs the non-manual marker co-occurs with.

Check yourself!

References and further resources

Attribution

Portions of this section are adapted from the following CC BY NC SA source:

↪️ Anderson, Catherine, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi. 2022. Chapter 3: Phonetics. Essentials of Linguistics, 2nd edition. Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics2/part/3-phonetics/

For a general audience

Melissa Cayton Coda THAT! 2021. Advanced ASL: Classifiers “How to describe things?! Learn American Sign Language! YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gifQclSut_k

Academic sources

📑 Baker, Anne, Beppie van den Bogaerde, Roland Pfau, and Trude Schermer. 2016. Appendix 1: Notation conventions. The Linguistics of Sign Languages: An Introduction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 337–341.

Hochgesang, Julie A. 2014. Using design principles to consider representation of the hand in some notation systems. Sign Language Studies 14(4): 488–542.

Marsaja, I. Gede. 2008. Desa Kolok: A deaf village and its sign language in Bali, Indonesia. Nijmegen: Ishara Press.

Nyst, Victoria. 2007. A descriptive analysis of Adamorobe Sign Language (Ghana). University of Amsterdam PhD dissertation.

Nyst, Victoria. 2012. Shared sign languages. In Sign language: An international handbook, ed. Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach, and Bencie Woll, 552–574. De Gruyter Mouton.

Sandler, Wendy, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign language and linguistic universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schuit, Joke, Anne Baker, and Roland Pfau. 2011. Inuit Sign Language: A contribution to sign language typology. Linguistics in Amsterdam 4 (1).