5. Decolonizing linguistics

Case study: Colonial practices in the early linguistic research of Franz Boas and George Hunt

Melissa Curatolo

Early modern linguistics and anthropology in North America evolved from an entangled relationship in the nineteenth century into two distinct disciplines today. Originally, the overarching trend in these fields was to arrange cultures on a hierarchy of ‘progress.’ Early scholars essentially studied particular non-Western societies through the lens of classical evolutionism theory, meaning they were compared to Western cultural values. In regards to languages, these were typically studied for their similarity or differences to commonly spoken European languages. Due to these colonial origins, the most prominent and noted names in these fields are male European names (Eriksen 2015).

You may have heard of Franz Boas, who is credited as a ‘founding father’ of American anthropology and an influential figure in modern American linguistics. Franz Boas is one of many well-known scholars attributed in the histories of linguistics and anthropology. There were, of course, numerous individuals conducting research during this early era of linguistics who did not receive as much credit. What kind of person do you think was more likely to receive credit?

Indigenous linguists and ethnographers, for example, have contributed enormously to the origins of modern linguistics. Frequently referred to as informants, Indigenous researchers and ethnographers were integral to the early founding of American anthropology and linguistics. They also deserve the immense recognition that their settler counterparts are given (Bruchac 2018: 19).

Valuable earlier work by Indigenous linguists and women is marginalized to this day. Part of acknowledging the colonial history of linguistics includes learning which scholars and intellectuals are being prioritized and who is being overlooked; the next step is to change this. Have you heard of the linguist and ethnographer George Hunt? What if we told you that he collaborated with Boas for over four decades?

Who was George Hunt?

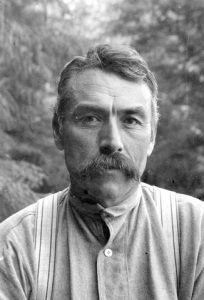

George Hunt (1854 – 1933) was a Tlingit-English linguist, ethnographer, interpreter, and collector who was born and raised in Kwakwaka‘wakw territory (in so-called Fort Rupert, British Columbia, Canada). Hunt spoke Tlingit, English, and Kwak’wala (Berman 1994: 12). Hunt worked as an interpreter and guide for missionaries, colonial government officials, and research expeditions due to his skill as a translator and his cultural knowledge (Berman 1994: 24–27; Bruchac 2018: 21).

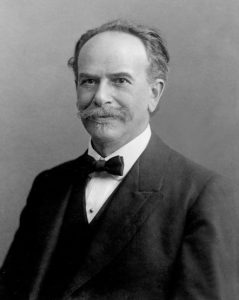

Hunt is most known for his collaborations with, and contributions to, the ethnographic work of Franz Boas. Franz Uri Boas (1858 – 1942) was a German-American anthropologist who is considered to be a founding influence in modern American anthropology and its schools of thought. Boas is attributed with popularizing the theory of cultural relativism, a view considered radical in his time because it began to counter racist ideologies. Cultural relativity is the idea that a culture and its beliefs, standards, and thoughts should be understood within its cultural framework – not in the context of different cultures (Bruchac 2018: 20; Eriksen 2015: 765–766).

Cultural relativism developed as a response to classical social evolutionism and ethnocentrism. Evolutionist anthropologists formed racist ‘classifications’ and ranked cultures hierarchically in comparison with Western “‘levels of development’,” ethnocentrically judging cultures against their own Western ideals (Eriksen 2015: 766). Despite his progressive cultural relativism, Boas still acted superior to Hunt and was ethnocentric in his approach. For example, Hunt wrote about some food-related topics, but Boas deemed these papers as less important due to his own cultural context (Bruchac 2018: 34).

Hunt and Boas’ working relationship evolved from Boas hiring Hunt as an expedition guide, to later hiring Hunt as an informant, consultant, collector, and author (Bruchac 2018). Throughout their decades-long correspondence, Boas exploited Hunt by encouraging Hunt to source and obtain cultural information and material items for museum exhibits. Hunt sometimes violated traditional protocol to secure material for Boas, such as secretly excavating Koskemo gravesites to collect human skulls and funeral items (Bruchac 2018: 31).

Undervalued contributors: Lucy Homikanis Hunt and Tsukwani Francine Hunt

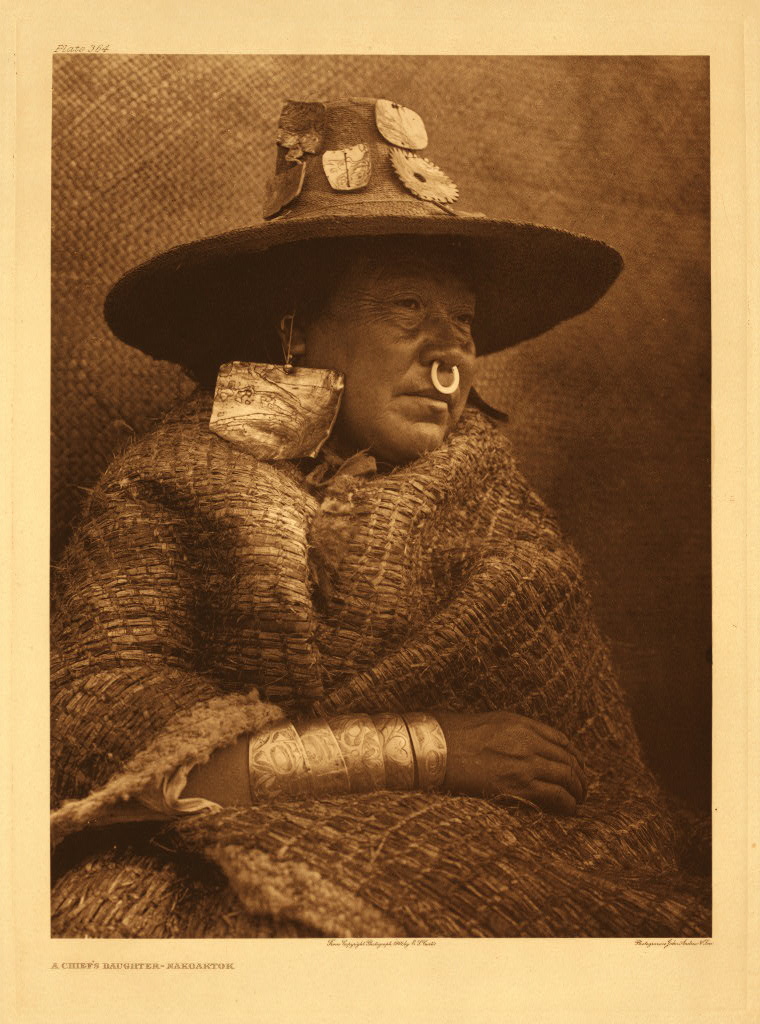

Despite Hunt’s Tlingit background, he was mostly an informant about the Kwakwaka’wakw culture and language. He wrote extensively about Kwakwaka’wakw practices, procedures, and other aspects of daily life, including Kwak’wala “myths, folktales, genealogical histories, and other narratives … prayers, ceremonial and everyday songs, and dreams” in his manuscripts (Berman 1994: 37). Hunt accessed certain Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonies and different types of knowledge through his two marriages to his first and second wives and their high-ranking families.

In 1872, George Hunt married his first wife Lucy Homikanis Hunt, the daughter of a Kwakwaka’wakw chief (Bruchac 2018). Hunt depended on Lucy for her invaluable knowledge and manuscript revision. She often reviewed Hunt’s writing, at times suggesting manuscript topics. Lucy “participated in recounting, recording, and translating traditions that were virtually unknown to her husband” and aided him when he forgot to include something (Bruchac 2018: 34–35). Her death in 1908 left Hunt in mourning. Hunt temporarily stopped communication with Boas, struggling for years to write with his grief and without her vital contributions (Bruchac 2018: 35).

Nearly a decade later, Hunt married his second wife, a high-ranking Kwakwaka’wakw woman named Tsukwani Francine Hunt (Bruchac 2018: 35). Their marriage inspired Hunt to continue his ethnographic work with Boas. While sleeping, Tsukwani sometimes sang and spoke to spirits. With Hunt nearby transcribing what she said, he recorded what was otherwise inaccessible information for Boas (Bruchac 2018: 37). Hunt usually credited his female informants in his manuscripts, but Boas did not include these attributions in the texts’ final versions (Bruchac 2018). Boas diminished the important cultural role of Kwakwaka’wakw women “as carriers and inheritors of tradition” when he dismissed the vital contributions of Lucy Homikanis Hunt and Tsukwani Francine Hunt (Bruchac 2018: 24).

Integral insights, discredited: Boas and Hunt

Boas also devalued Hunt’s writing abilities and transcriptions. Hunt often spelled Kwak’wala words closer to their phonemic transcription, meaning he represented more of the individual sounds in his writing. Boas called these practices ‘errors,’ despite some actually being linguistic insights. Boas complicated his orthography by excessively marking vowel allophones or variants and omitting secondary articulatory features on consonants. Instead of using Boas’ method, Hunt’s transcriptions would, for example, represent certain vocalic segments as non-phonemic schwas preceded by a labialized consonant. This “treatment of non-phonemic schwa” influenced Boas’ later unpublished writing about Kwak’wala root structure (Berman 1994: 46).

Although Hunt was technically credited by Boas, “Boas asserted intellectual dominance by characterizing himself as Hunt’s language instructor, editor, and proofreader” in his acknowledgments (Bruchac 2018: 41). Hunt and Boas co-authored three books on Kwak’wala, with Boas publishing additional articles and texts under his own name from Hunt’s ethnographic collection (Bruchac 2018: 21). Seeing “Boas’ name alone on the cover of most of these volumes” misrepresents Hunt’s immense contributions to these ethnographic and linguistic materials (Berman 2001: 204).

Boas and Hunt’s forty years of work is invaluable, but it is not without bias. Hunt and Boas only give partial insight to Kwakwaka’wakw life at the time. While “Boas’ output on the Kwakwaka’wakw was dependent upon Hunt’s vast knowledge and ceaseless labor,” Hunt himself was dependent on the essential input and generosity of his wives Lucy and Tsukwani, their families, and other Kwakwaka’wakw members (Berman 2001: 204). However, their level of input is not enough. Even still, their voices are filtered through Hunt and Boas’ writing. Lucy and Tsukwani are cultural knowledge carriers; this filtration is clearly unnecessary.

Hunt and Boas’ work only tells one part of the story. This history begs the questions, whose voices are centred and what might be missing?

Connecting this history to modern linguistics

- How can we learn from Boas’ mistakes?

- What do we need to keep in mind when using Boas and Hunt’s research in current times?

- Hunt and Boas’ research notes are still actively being used in modern linguistics research. Is it possible to use it ethically and critically? Why and how, or why not?

- Who should control the archives of Boas and Hunt’s work?

Key takeaways

- George Hunt was a Tlingit-English linguist who conducted ethnographic fieldwork with Franz Boas and his wives Lucy Homikanis Hunt and Tsukwani Francine Hunt, researching and writing about the Kwakwaka’wakw and their Kwak’wala language.

- Although Boas also popularized cultural relativism, a progressive anthropological theory for the time, the work he and Hunt did had many ethical issues.

- By examining the past with a critically-informed perspective, we can learn how to be better scholars and researchers today. Identifying the ethical issues in this case study can help us apply what we learned to our own work.

Check yourself!

References and further resources

Academic sources

Berman, Judith. 1994. Raven and sunbeam, pencil and paper: George Hunt of Fort Rupert, British Columbia. Ms., University of Pennsylvania. https://www.academia.edu/33041956/Raven_and_Sunbeam_pencil_and_paper_George_Hunt_of_Fort_Rupert_British_Columbia

Berman, Judith. 2001. Unpublished materials of Franz Boas and George Hunt:

A record of 45 years of collaboration. In Gateways: Exploring the legacy of the Jesup North Pacific expedition, 1897-1902, ed. Igor Krupnik and William W. Fitzhugh, 181–213. Washington, D.C.: Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

🔍 Bruchac, Margaret M. 2018. Finding our dances: George Hunt and Franz Boas. In Savage kin: Indigenous informants and American anthropologists, 20–47. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Eriksen, Thomas H. 2015. Anthropology and history. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2nd edition, ed. James D. Wright, 1: 765–771. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.03025-7