6. Kinds of morphemes and morphological processes

6.8. Becoming a linguist: Anatomy of an academic article

The first page

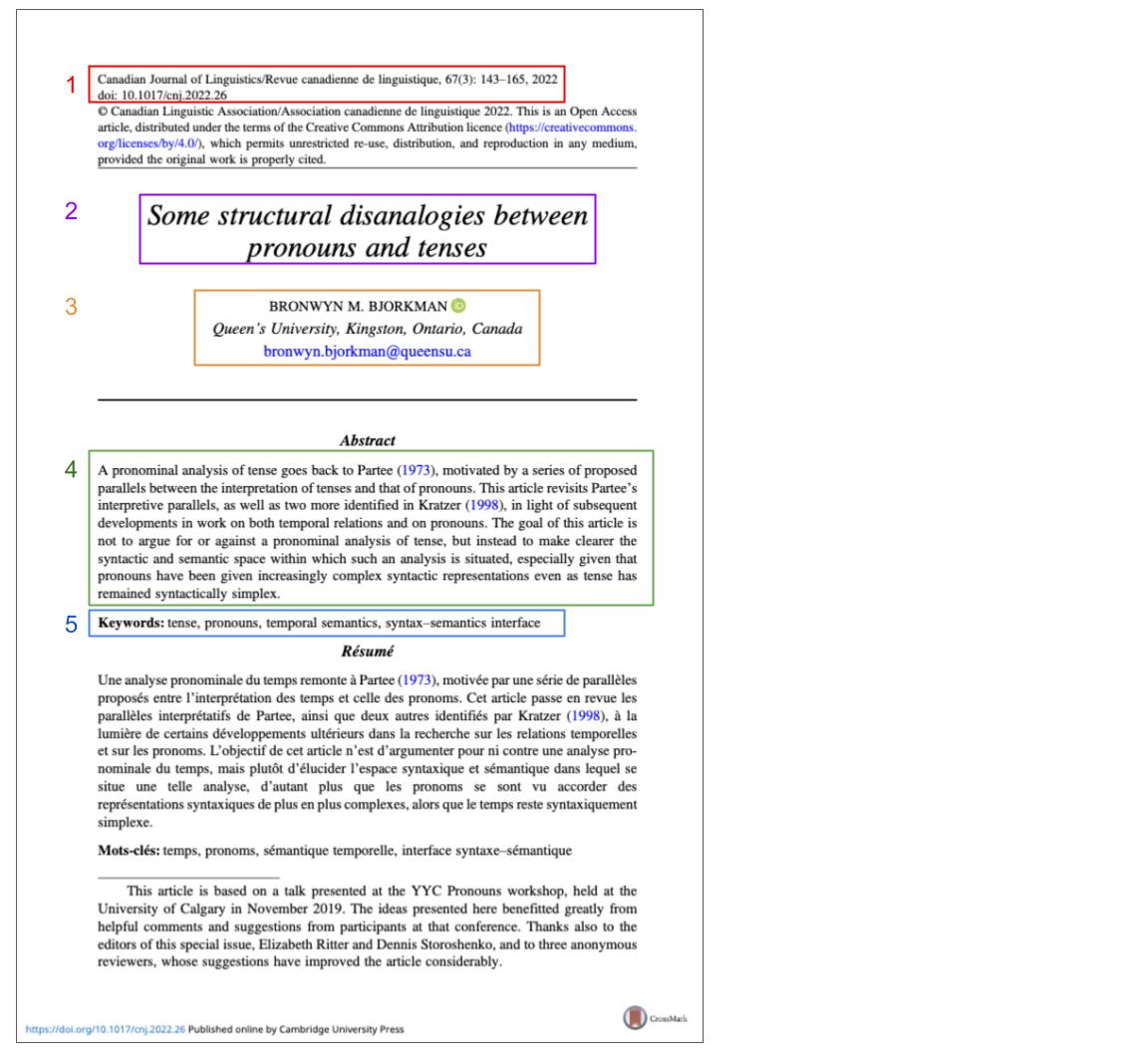

The first page of an academic article has lots of useful information, as shown in the annotated picture of the first page of Bjorkman (2022) in Figure 1. I’ve marked five areas where you should look when first navigating an academic article, which I will explain below. This article is published in the Canadian Journal of Linguistics. Other journals will have different layouts, but they will generally be similar and have many of the same elements.

Box 1 (red): The publication information

At the top of the page, as part of the header, the publication information of the article is listed. In this case, it includes the journal title, the volume and issue numbers, the page numbers, the year of publication, and the DOI, which is a unique number assigned to academic articles to help you find them. You will need this information in order to write a citation for the article. In some journals, this could be listed on the bottom of the page or on a cover page before the article begins, instead.

Box 2 (purple): The title

This is the name of the article, and one of the first things you will look at when deciding whether you should read an article.

The title of this article is Some structural disanalogies between pronouns and tense. What can you tell about this article based on this title?

- The paper is probably written in English, since the title is in English.

- It is about the structure of pronouns and tenses, and so is probably related to the fields of morphology, syntax, and/or semantics.

- The word disanalogies suggests that it is about how pronouns and tense are different from each other.

Box 3 (orange): The author’s information

The author of the article is usually listed underneath the title, alongside other information about the author, such as their affiliation. This article is written by Bronwyn Bjorkman who is affiliated with Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

This article also provides the author’s email. If you do wish to contact an author, I recommend googling them, in case their contact information has changed since the publication of the paper.

Box 4 (green): The abstract

Underneath the author’s information is a paragraph labeled abstract. When abstract is used as an adjective, it usually means the opposite of concrete. But when abstract is used as a noun, especially in academic settings, it usually means a summary that you can use to decide whether you want to engage with a bigger work. You can think of the abstract as a movie trailer or the blurb on the back of a book.

Not all journal formats include a header labeling the abstract. Sometimes, the abstract will just be found at the beginning of the paper in a box or a different font. More rarely, a paper may not have an abstract at all.

Here is the text of this article’s abstract:

A pronominal analysis of tense goes back to Partee (1973), motivated by a series of proposed parallels between the interpretation of tenses and that of pronouns. This article revisits Partee’s interpretive parallels, as well as two more identified in Kratzer (1998), in light of subsequent developments in work on both temporal relations and on pronouns. The goal of this article is not to argue for or against a pronominal analysis of tense, but instead to make clearer the syntactic and semantic space within which such an analysis is situated, especially given that pronouns have been given increasingly complex syntactic representations even as tense has remained syntactically simplex.

-Bjorkman 2022: 143

Here’s what you can tell from this abstract:

- Partee (1973) and Kratzer (1998) argue that there are some parallels between tense and pronouns, and they use those parallels to provide an analysis of tense.

Note: Barbara Partee and Angelika Kratzer are both very well-known and influential semanticists. Their status combined with the age of their articles suggests that their analyses of tense have been very important, perhaps foundational. - These analyses are about the interpretation of tense and pronouns, which suggests that this article may include some semantic analysis.

- More work has been done on tense and on pronouns since Partee’s and Kratzer’s articles were published, which is why their analyses are worth revisiting.

- The article does not necessarily contradict Partee and Kratzer.

- One difference between pronouns and tense is that pronouns tend to be analyzed as having complex syntactic structures but tense as having simpler structure.

Because the CJL is a bilingual publication, it provides abstracts for all of its papers in both French and English (even though the papers themselves are not bilingual). In this case, the French abstract is below the English one, labeled Résumé.

Different kinds of academic materials have different kinds of abstracts, with some differences. For example, the abstract of an academic article, like this one, is only about a paragraph long. It won’t usually include references or headings (although in some other fields, it may). It is usually provided right before the article it is about.

The abstract for a conference presentation, in contrast, is often submitted anonymously months before the conference begins, and is used to determine which presentations are included in the conference. The selected abstracts will then be de-anonymized and published on the conference website, so that people can use them to decide which presentations to attend. Conference abstracts are usually one or two pages long, with strict page limits set by the conference organizers. Headings are usually used to conserve space and direct the readers’ attention, and an abbreviated reference list may be included at the end.

Box 5 (blue): Keywords

Underneath the abstract, you will often find keywords, although not all journals include keywords for their articles. These keywords give you more clues about what the article is about. The keywords will often indicate which languages are being analyzed, which subfields of linguistics the article can be classified under, and which grammatical properties are being analyzed.

The keywords for this paper are tense, pronouns, temporal semantics, and syntax–semantics interface. Here’s what you can tell from the keywords:

- We can confirm that the main topics of the paper are tense and pronouns (which we already figured out from the title and abstract).

- The main subfield of this paper is probably semantics, but it is also relevant to syntax.

This paper also includes French keywords underneath the French abstract, under the label Mots-clés.

The body of the paper

The body of the paper will probably be divided into numbered sections and subsections. As mentioned in Section 2.6, morphosyntax papers don’t usually have a formulaic structure. Instead, the structure will typically be described in an outline at the end of the introduction.

Throughout the paper, you may find tables, graphs, linguistic data, syntax trees, and other formalisms. These will typically be numbered and discussed in the text. It is not considered acceptable to include data and formalisms without providing a description, relevant context, and explanation. If you are not sure how to interpret the data or formalisms, the discussion in the text may help you to understand them better.

The fine print

Footnotes and endnotes

Academic papers tend to have a lot of additional notes. If they are found at the bottom of each page throughout the paper, they are called footnotes. If they are found at the end of the paper, they are called endnotes. Papers will either use one or the other, not both.

When you are writing a paper, don’t go out of your way to include footnotes or endnotes. If it is important, it should be included in the main text, not in a note. In published papers, many of the footnotes or endnotes get added through the review process, as responses to the reviewers.

Footnotes and endnotes may contain points of clarification or additional details. A lot of researchers hide their problems and limitations in their notes, so if you are writing a critique of a paper or looking for ideas for further research, reading the notes can be helpful.

In some citation styles, references are included in the notes. As described in Section 2.7, we typically use in-text citations in linguistics instead.

Acknowledgements

There will typically be an acknowledgements section included in the article. This may be found as a footnote on the title or in a special section at the end of the article. If the researchers collected data using elicitation, their language consultants will often be thanked in the acknowledgements section, giving you more information about how the data was collected.

Abbreviations list

If there is glossed linguistic data, an abbreviations list should be included in the article. This may be found in a footnote on the first example or at the end of the article in a special section.

References

At the end of the article, there will be a references list. The references list should include the full bibliographic information of every source cited in the paper. The format of the references list used in the Canadian Journal of Linguistics is described in detail in Section 2.7.

Key takeaways

- On the front page of an academic article, you should be able to find the title, the author’s information, the bibliographic information of the article, a summary of the article called an abstract, and sometimes article keywords.

- The main body of the paper will usually be divided into numbered sections and subsections. The organization of the paper will often be described at the end of the introduction.

- Data and formalisms included throughout the paper will be numbered and should be described in the main text.

- Footnotes and endnotes can be a good place to find problems with the paper or areas of further research.

- Papers will often have acknowledgements and abbreviations list that can provide information to help you interpret the data in the paper.

- Academic articles should always end with a references section that provide the full bibliographic information of all sources cited in the article.

Check yourself!

References and further resources

Sources for examples

Bjorkman, Bronwyn. 2022. Some structural disanalogies between pronouns and tenses. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 67 (Special Issue 3: Pronouns): 143-165.

A category of words. Note that pronouns are not nouns. They are determiners.

Verbal inflection that indicates when the event took place, such as past, present, or future marking.