Part 2: Planning

9. Implementing Strategy

- Learning Goals

- 9.0. Opening Case: A Business Where Employees Choose Their Own Hours and Pay

- 9.1. Introduction

- 9.2. Step 1: Develop Operational Goals

- 9.3. Step 2: Develop Operational Plans

- 9.4. Step 3: Implement and Monitor Goals and Plans

- 9.5. Step 4: Learn from the Strategy in Action

- 9.6. Entrepreneurial Implications: Stakeholder Maps

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

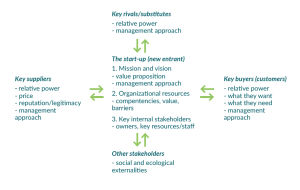

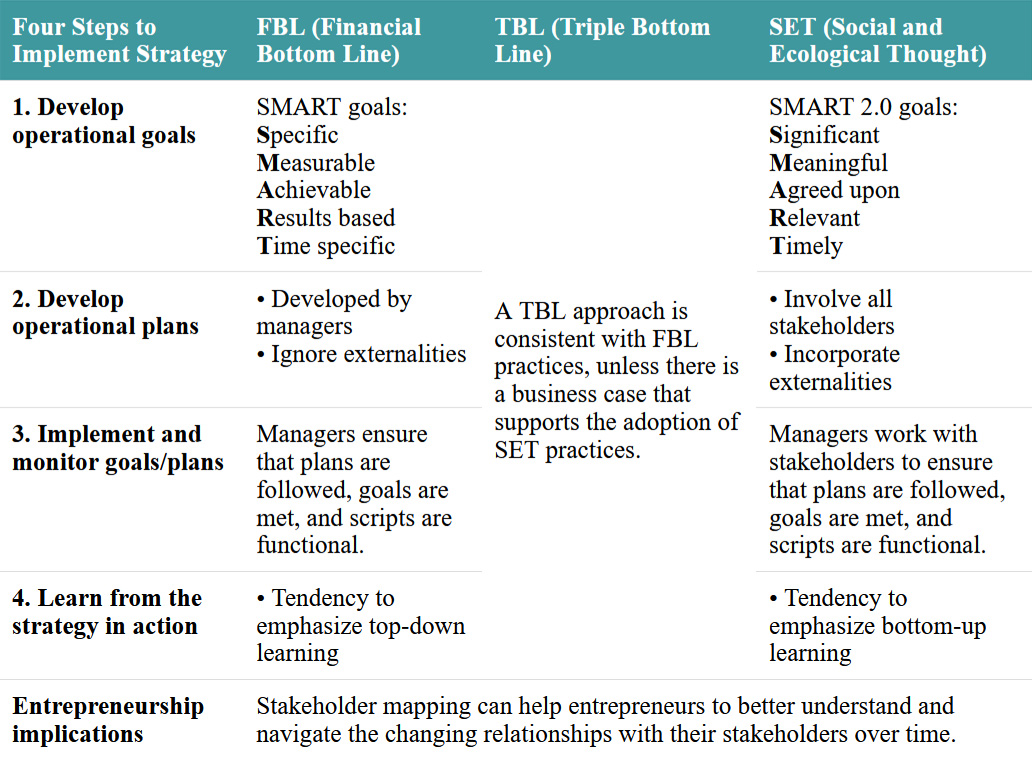

Chapter 9 provides an overview of the four steps of implementing organizational strategy, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the four steps to implement strategy, including the differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

- Explain the difference between SMART and SMART 2.0 goals.

- Describe the five steps in making operational plans.

- Describe the hallmarks of strategic learning.

- Describe how stakeholder mapping can help entrepreneurs to formulate, implement, and reformulate strategy.

9.0. Opening Case: A Business Where Employees Choose Their Own Hours and Pay

When COVID-19 restrictions were imposed in 2020, prompting many businesses to close down, Nathaniel De Avila began to develop a strategy for a new start-up based in Winnipeg.[1] He envisioned a home renovation company that would enhance social and ecological well-being. In contrast to firms in the construction industry known for creating a lot of waste and for treating entry-level employees poorly, De Avila’s vision was to provide meaningful work, especially for people facing barriers to employment, to help homeowners who value sustainable practices, and to collaborate with other sustainability-minded companies. In short, he wanted his firm to pursue elements of the minimizer (reducing waste, greenhouse gases or GHGs) and transformer (providing life-giving work for unemployed people and treating them with dignity) strategies, and thereby become a sustainability hero (see Chapter 8).

Of course, formulating an ambitious strategy is quite different from implementing it. The first step in implementation is to develop specific goals that support the overall strategy. De Avila set four key goals. First, to reduce GHG emissions caused by driving trucks, he set the goal of having co-workers cycle to work year-round (even in winter, when temperatures reach –20° Celsius or lower). This goal is reflected in the name he chose for the company, Velo Renovation (velo is the French word for bicycle). Second, he set a goal to find meaningful renovation projects to work on, which meant encouraging customers to recycle materials, reducing the use of new materials, and purchasing environmentally friendly products (e.g., linseed instead of acrylic paint). The third goal was to treat employees with dignity, leading to policies that allowed workers to choose their own hours and their own pay. Fourth, he set a goal to hire marginalized people, even when doing so would increase the need for training.

Because his strategy and goals were quite bold, De Avila was not confident that they could be achieved. He chose to view Velo as an experiment and not to worry that it might fail. This orientation allowed him to be flexible in developing and implementing his plans. For example, he sought to hire people who needed a job, preferably people with barriers to entry (e.g., BIPOC, those negatively affected by COVID-19, someone facing a mental health issue), and personally provided on-the-job training as required. This sometimes meant hiring people who needed a job, even when not specifically recruiting for someone (such as happened when De Avila’s friend met someone in the neighborhood who asked for a job but lacked qualifications).

Velo’s flexibility is also evident many other ways. For example, during the period that government provided grants to firms like Velo to help pay for the extra hardships caused by COVID-19, Velo did not need those funds to cover operational costs, so De Avila happily shared them with co-workers. Likewise, ensuring co-workers do not fear losing their jobs if they make mistakes is more important at Velo than doing work exactly as planned. Finally, De Avila ensures that employees and other stakeholders are involved in making plans and are provided the information to make them (e.g., the company’s financial information is available to all employees).

One of De Avila’s early goals, namely to step away from the company’s leadership role and pass it to others within six months, still hadn’t been fulfilled after four years of being in business. This failure was not because of a lack of effort. For example, De Avila was out of the country for months at a time on several occasions and left the management of daily operations to co-workers, hoping that they would gain the confidence, skills, and interest to take over. Co-workers were happy to help out when De Avila was gone but preferred to stay in their previous roles in the long term. As a result, and as an example of learning from its strategy in action, Velo became more deliberate in recruiting people to take over De Avila’s role. Another example of strategic learning was evident when the renovation industry was hurting as a result of higher interest rates, which reduced homeowners’ budgets for such work. In response, Velo tweaked the way it paid people and moved toward a profit-sharing model.

Like many small firms, Velo faces an uncertain future. De Avila remains unconvinced about the financial viability of its unusual strategy, but some employees are more optimistic. In any case, De Avila is ready to pass on the baton of leadership and curious to see what further lessons and changes await Velo.

A short video that features Velo Renovation (https://youtu.be/WbNAWXGdzgM).

9.1. Introduction

The previous chapter described the four steps associated with formulating strategy: establish the mission and vision (step 1), complete a SWOT analysis of strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats (steps 2 and 3), and then select and develop an appropriate strategy. Formulating strategy is important, but a well-formulated strategy that is not implemented is of little value to organizations. It is one thing to come up with ideas about what could be done, and something quite different to get them done. In fact, only 15 percent of major strategic change attempts are successfully implemented.[2]

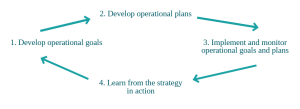

Whereas the previous chapter looked at the content of formulating strategy, this chapter looks at the process of implementing strategy. This involves everyone in the organization, including stakeholders. As shown in Figure 9.1, this chapter examines how managers put strategies into action via the ongoing process of setting operational goals (step 1) and making operational plans (step 2), implementing and monitoring those operational goals and plans (step 3), and learning from this process to reformulate strategy (step 4). As in other chapters, we will highlight the differences between the Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) approaches to formulating strategy.

Figure 9.1. Four steps of strategy implementation

9.2. Step 1: Develop Operational Goals

Once a strategy has been formulated, the first step in implementing it is to develop operational goals. Operational goals are outcomes to be achieved by an organizational department, workgroup, or individual member. Operational goals serve to spell out the practical implications of strategic goals. The time horizon of operational goals is typically one year or less, and they can be seen as the building blocks of longer-term strategic goals (which tend to require one to five years), which in turn are expressions of even longer-term vision statements (which tend to last five years or longer). People are usually able to focus on three to seven operational goals at a time, depending on how complex the goals are and how much time is available to reach them.[3]

Although we will use the term “goals” throughout this section, other words can be used to describe operational goals. For example, Microsoft has preferred the word “commitments” to “goals.” The “commitment” terminology came from managers who believed that it would make members more accountable and more likely to meet the goals.[4] “Standards” is another term that is sometimes used instead of “goals.” Some goals serve as performance standards, which are metrics used to determine how well a particular employee, department, or organization is doing its work.

9.2.1. The FBL Approach to Operational Goals

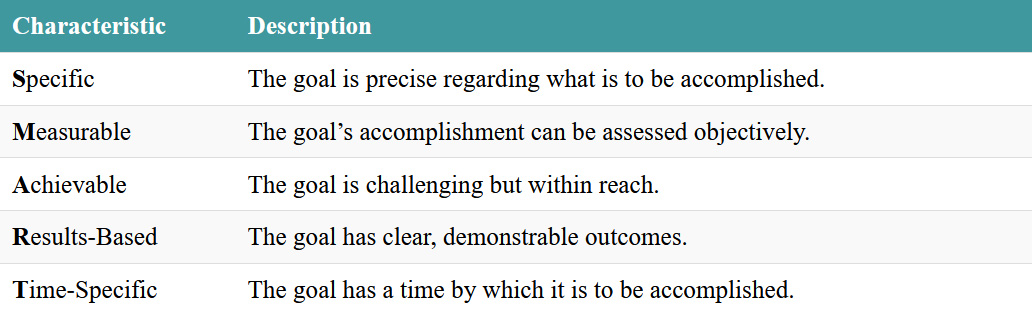

Under the FBL perspective, operational goals are typically set by mid- and lower-level managers and supervisors. Goal-setting research has found that financial performance is maximized when goals have certain characteristics. The acronym SMART draws attention to the characteristics that a goal should have (see Table 9.1). It might seem like these characteristics are simply common sense and easy to implement. However, managers need to ensure that they are developed and implemented properly. For example, after an audit was done on SMART goals at Microsoft, managers discovered that about 25 percent of members’ goals were not specific and that over 50 percent were not measurable.[5]

Table 9.1. Five characteristics of SMART goals (associated with FBL management)

First, SMART goals are specific. Having a specific goal clarifies expectations and improves performance.[6] For example, rather than simply trying to increase sales revenue, managers at Microsoft could set a specific goal to increase the sales of Microsoft Office software by targeting business customers in the United Kingdom. The more specific the goal is, the more likely it is to be accomplished.

Second, SMART goals are measurable. Managers must be able to measure whether goals are being met. Doing so may mean using existing data (for example, total sales revenue of Microsoft Office software in the United Kingdom) or setting up systems to collect the desired data (for example, determining the size of businesses that purchase Office software). Measurable goals provide feedback so people can evaluate whether their behavior is serving to meet the goal or whether their actions should change.

Third, SMART goals are achievable. It should be possible to reach the goal, but the goal should not be easy. Research suggests that people perform better when they are given challenging goals rather than easy goals or told to “do your best.”[7] For example, a C student who sets the goal of reaching a C is likely to succeed (the goal is a little bit challenging, but readily achievable). Likewise, a C student who sets a goal of reaching a B grade is also likely to succeed (more challenging, yet still attainable). However, a C student who sets the goal of getting an A may quit halfway through a course upon realizing that an A is too challenging and not attainable.[8]

Fourth, SMART goals are results based. Goals should focus on specific outcomes, not simply on performing activities. This was a major concern at Microsoft, where an emphasis on activities without including results was an important contributor to its lack of SMART goals. The following example describes how a shift from activity-based to results-based goals led to improved performance.[9] A senior vice-president (VP) met with the recruiting manager from the human resources department to request that more people be recruited for the VP’s work unit in the coming year. Prior to this meeting, the recruiting manager had been told by her own boss, “Whatever he says, do not agree to a specific number of new hires for next year.” In other words, the recruiting manager was to agree to recruit people for the VP’s work unit (activity), but she was not to set any target (results). As predicted, the senior VP kept pushing for a target, but none was forthcoming. Finally, he said, “If you won’t give me a number, then I’m going to give you one,” and gave a goal that was twice the number from the previous year, and much higher than the recruiting team thought possible. The senior VP also promised that if the target was achieved, he would throw a big party for the recruiting team at his home. The goal was achieved and surpassed by a third, and they partied. This example illustrates the importance of adding a results-based target to relevant activities. It also points to the importance of rewarding members for achieving targeted results. However, safeguards must be put in place to ensure members don’t “cheat” to achieve their results and rewards (e.g., members may be tempted to reduce quality in order to meet quantity goals, or to ignore long-term maintenance needs in order to meet short-term production goals).[10] For these and other reasons, it is important for supervisors who assign multiple goals to indicate which goals and results have the highest priority (e.g., that quality is more important than quantity).[11]

Finally, SMART goals are time specific. Having a deadline provides a sense of urgency for members to reach their goals, and also helps managers to reconsider goals on a regular basis. To go back to our example of Microsoft Office software, it would make a big difference whether the deadline to achieve a 30 percent increase in sales was set at six months or at six years. An example of a SMART goal would be “To increase sales of Microsoft Office software by 30 percent in the United Kingdom within six months.”

9.2.2. The SET Approach to Operational Goals

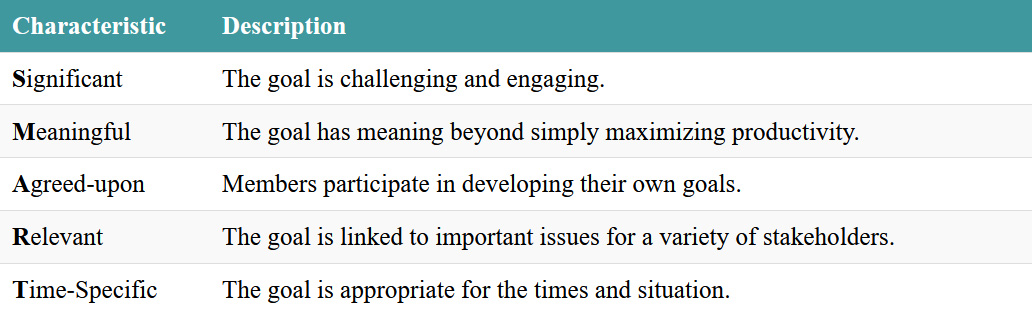

SMART goals can be used to improve productivity and are consistent with FBL management. Although SET managers also value productivity, they are more likely to use a parallel process that develops SMART 2.0 goals (see Table 9.2). TBL managers tend to use SMART goals unless SMART 2.0 goals help to improve financial well-being. Some of the characteristics of SMART 2.0 goals are consistent with SMART goals, including setting achievable goals that are also challenging. However, SET managers do not fully embrace several of the other SMART criteria. Most notably, SET managers are concerned that a single-minded focus on measurable goals may cause managers to ignore significant outcomes that are more difficult to measure. For example, while a focus on measurable goals increases productivity, at the same time it decreases important behaviors that are often not measured or that may be more difficult to measure, such as treating people with dignity, helping co-workers, or creating positive social and ecological externalities.[12] This change in behavior is an example of goal displacement, which happens when people become so focused on specific goals that they lose sight of other, more important goals.

Table 9.2. Five characteristics of SMART 2.0 goals (SET management)

First, SMART 2.0 goals are significant in terms of being both challenging and motivating to members. The idea of goals that are challenging is consistent with SMART goals that are challenging yet attainable. For example, LEGO is committed to using sustainable materials to manufacture all of its core products by 2030.[13]

Second, SMART 2.0 goals are meaningful in that they go beyond simply maximizing productivity or financial well-being. Meaningful goals enable employees to connect their job to their personal sense of purpose, to make a positive difference in the world, and to feel more valued and have a sense of belonging in their workplace.[14] Employees at Velo find it meaningful to help clients renovate their homes in sustainable ways (see opening case).

Third, SMART 2.0 goals are agreed upon by the people who are expected to implement them. Whereas the FBL approach favors top-down assignment of goals, a SET approach is much more open to bottom-up involvement. While the FBL approach advocates participation in goal setting in some circumstances (such as when participation can help to resolve conflict among multiple goals[15]), the SET approach welcomes participation even if it does not provide cost savings to the organization.[16] This participation can take place between a member and a manager, or in larger meetings where members develop group goals and plans. Group participation makes members even more aware of the resources and responsibilities of each member, and because the goals and plans are connected, members will be more sensitive to the need for changing or fine-tuning goals and plans. For example, managers at Eliza Jennings Group—a nonprofit organization that provides a range of services for older adults—involve stakeholders to develop and agree upon goals. The stakeholders include employees as well as patients and their families. As a result, each feels a greater ownership of the goals and an improved appreciation for the contribution of other stakeholders.[17]

Fourth, SMART 2.0 goals are relevant, both to the organization’s mission and vision and to the aspirations of members and other stakeholders. Of course, FBL goals are also relevant, with a primary focus on goals related to productivity and financial well-being. In a SET approach, in addition to attending to financial well-being, goals are also relevant to social and ecological well-being. Because SET managers are concerned about a variety of forms of well-being and stakeholders, they may have socio-ecological goals that are not relevant for FBL managers. This is evident in the emphasis at Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company on treating all stakeholders with respect: “Respect, I think, is at the heart of it. Respect the people who grow [suppliers], respect the land itself [nature], respect the people who work [employees], and respect the customers. Respect all through the circle.” Because of this participatively developed goal of respect, Tall Grass pays farmers more than twice the market rate for local organic flour and pays employees at least a living wage. The owners do not even consider copying other bakeries that pay less in order to increase profits.[18]

Finally, SMART 2.0 goals are timely. Given the social and ecological issues facing humankind (Chapters 4, 5), there is great need and opportunity for innovative thinking and goals that are consistent with the SET perspective.[19] SET firms often place greater emphasis on goals that enhance the sustainability of current operations (e.g., improve sustainability in their supply chain, enhance working conditions, minimize post-consumer waste) than on goals to grow or scale up (e.g., maximize sales, revenue, growth).[20]

Test Your Knowledge

9.3. Step 2: Develop Operational Plans

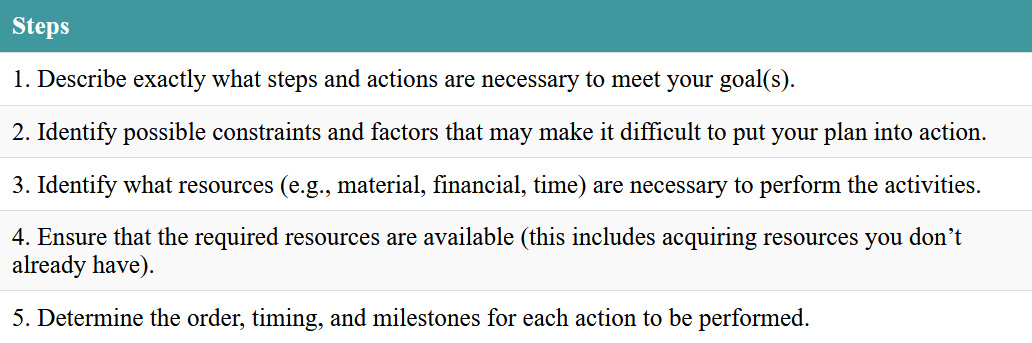

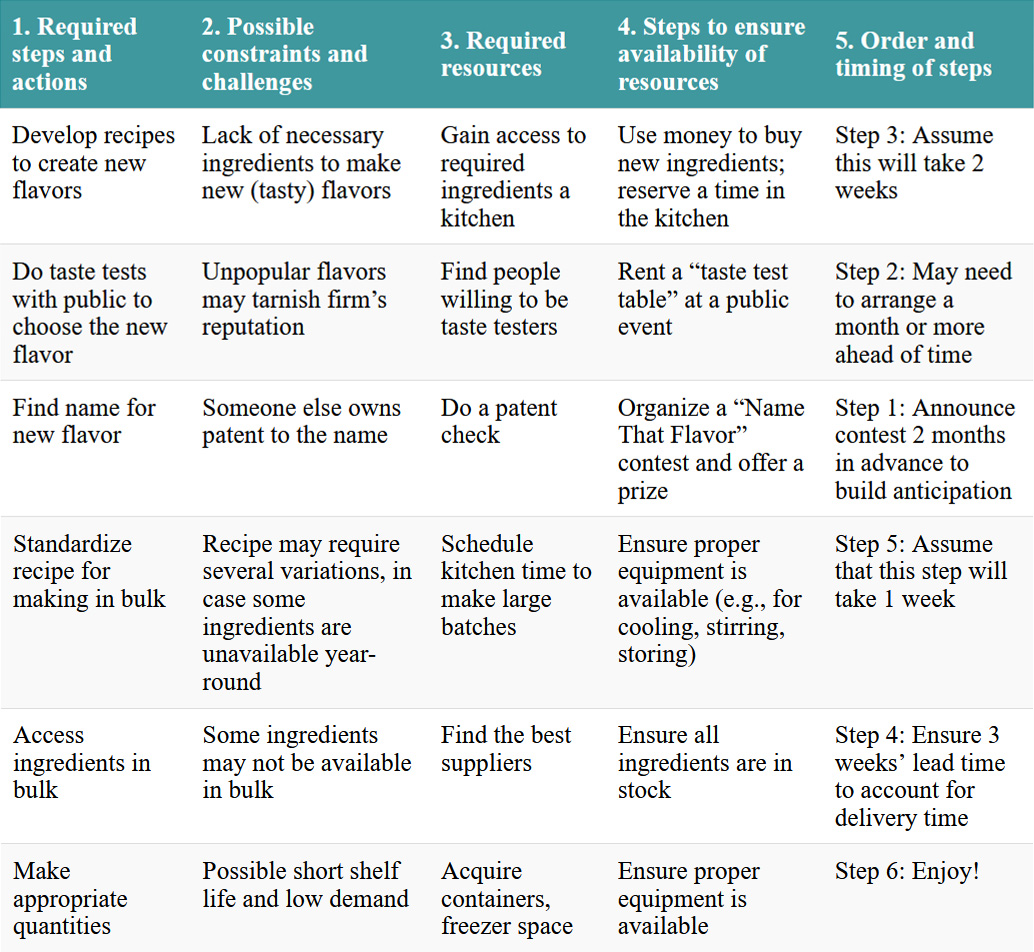

Once operational goals have been set, they serve as the basis and impetus for making operational plans. Operational plans specify what activities will be used to meet a goal, when they should be accomplished (in light of existing commitments and constraints), and how the required resources will be acquired. Table 9.3 provides a helpful checklist for developing multi-step operational plans that describe how each operational goal will be achieved. Such plans include identifying key dependencies and resources required to achieve the goal, and key milestones that describe what must be accomplished by when.

Table 9.3. Checklist for making a plan

Table 9.4 shows what the five items on the planning checklist might include if, for example, you work in an ice cream shop and your goal is to introduce a new flavor of ice cream. This goal might be consistent with a differentiation strategy and a vision to have more ice cream flavors than any other shop in the region. Or it be might consistent with a sustainability hero strategy and a vision to offer the healthiest locally made ice cream in the region. In either case, there are some key steps and actions you must perform to meet your goal, including experimenting with different recipes and combinations of ingredients (requires access to a kitchen); conducting taste tests with customers (requires access to a sample of people willing to try new flavors); thinking of a name for your new flavor (requires creativity and marketing skills); standardizing the recipe for making it in bulk (requires access to a kitchen and trial runs); acquiring ingredients (requires suppliers); and making the product in appropriate quantities (requires production facilities).

Table 9.4. Checklist for making a plan to develop a new ice cream flavor

9.3.1. Standing Plans

While many operational plans are intended for single use only, some are intended for repeated or ongoing use. Standing plans are operational plans for activities that are performed repeatedly. Standing plans share similarities with programmed decision-making as described in Chapter 7. For example, an organization may develop a unique single-use plan to launch a particular product but will have a standing plan for annual performance evaluations of staff. Standing plans can be further subdivided as follows:

- standard operating procedures

- policies

- rules and regulations.

Standard operating procedures outline specific steps that must be taken when performing recurring tasks. For example, Velo has standard operating procedures regarding the basic steps to transport ladders via bikes, and McDonald’s has standard operating procedures on how to assemble a Big Mac (what ingredients are used, and in what order they are assembled). Policies provide guidelines for making decisions and taking action in various situations. For example, retail stores have return policies that describe the conditions under which a customer can receive a full refund for a purchase, and universities have policies that describe the conditions when it may be possible to waive the prerequisites to register for specific courses or programs. Rules and regulations are prescribed patterns of behavior that guide work tasks. They tell people what can and cannot be done. For example, food preparation workers may be required to wear hairnets and wash their hands regularly; grocery store clerks may be required to wear their name tag at all times. Standard operating procedures, policies, and rules and regulations are all used to make programmed decisions (Chapter 7).

9.3.2. Contingency Planning

Sometimes managers develop operational goals and plans that they hope will never need to be implemented. Contingency plans, sometimes called scenarios, describe in advance how managers will respond to possible future events that could disrupt existing plans. For example, managers may determine what the effect of a sudden 10 percent decrease (or increase) in sales would be, and then develop plans to handle the situation. Similarly, organizations and cities are wise to develop contingency plans for responding to extreme weather events like hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and droughts.[21] An important part of contingency planning is to think about the various things that could lead to a crisis.

Crises are events that have a major effect on the ability of an organization’s members to carry on their daily tasks. There are three things managers can do to limit the impact of crises. First, they can do preventive work to avoid or minimize the effect of a crisis. For example, developing trusting relationships with employees may make a labor strike less likely, since workers enjoy a good working relationship with management.

Second, managers can prepare for a crisis by assembling information and defining responsibilities and procedures that will be helpful in a time of crisis. This includes things like designating a spokesperson to be the public face of the organization during the crisis, and deciding on the location from which the crisis will be managed. This location may be a specific room where the relevant information is stored and where access to communication systems is assured.

Third, managers can contain the crisis by making timely responses. This can help to minimize the damage, get the truth out, and meet safety and emotional needs. For example, if there is a fire in a factory, managers should call the fire department, inform neighbors of any potential dangers, contact family members of the factory workers, provide access to counseling services as needed, and phone key customers and suppliers to explain the implications of the fire.

9.3.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Operational Planning

FBL, TBL, and SET approaches follow similar checklists to develop plans, but there are notable differences in how plans are formulated. First, FBL managers tend to develop plans on their own, whereas planning in SET organizations is more likely to include other employees and stakeholders. TBL managers follow a SET approach if doing so enhances financial well-being. TBL and SET approaches are more likely to involve employees not only in order to increase their social well-being but also because they believe the variety of input will make for better plans. In addition to being more likely to seek the advice and participation of others, SET and TBL managers are more likely to consider a wider range of non-financial issues, thus making for a more holistic plan.

Because there are more factors to consider in planning from a SET perspective (i.e., factors related to a wider range of financial, social, and ecological goals), such operational plans often need to be more complex and emergent.[22] For instance, in the example of introducing a new flavor of ice cream, an FBL approach may focus on the tastiness and cost of ingredients in a recipe, but from a SET perspective the range of factors may be expanded to developing recipes using local, organic, and/or nutritious ingredients, or even introducing vegan ice cream![23] This complexity may also require SET plans to be more flexible and fluid, though the relative simplicity of FBL plans also facilitates quick adaptations.

Finally, when it comes to identifying constraints and preventing negative externalities, SET managers are more likely to consider the effects of their actions on the ecological environment and on other stakeholders. The operational plan for the person developing the new ice cream flavor in a SET organization may include collecting feedback not only from customers and suppliers but also from health professionals and from neighbors living near the ice cream shop (who may complain about customers leaving behind refuse that attracts wasps). After following this plan, the decision may be made to introduce a new ice cream flavor that has nutritional and ecological benefits and is only available in edible ice cream cones or biodegradable packaging that has no hard-to-reach crevices, thus minimizing the amount of wasted ice cream.

Test Your Knowledge

9.4. Step 3: Implement and Monitor Goals and Plans

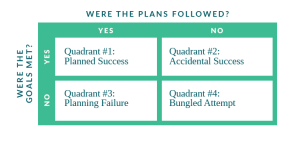

As shown in Figure 9.2, as plans are put into action there are four possible outcomes, depending on whether the plan is followed and whether the goal is met. We will discuss each possible outcome in turn.

The most desirable outcome is Quadrant 1—where the plan is followed and the goal is met—which suggests that the process of setting goals and making plans has worked as intended (planned success). Achieving this quadrant is especially important for standing plans in order to have a smooth-running organization. For example, if an ongoing goal is to pay employees on time, then it is important to develop standard operating procedures to allow this to occur. Note also that sometimes achieving goals may trigger the need to set new goals and make new plans. A classic example is the March of Dimes organization, whose mission was to eradicate polio. When this was achieved, the organization changed its mission to reducing birth defects.

Figure 9.2. Possible outcomes of implementing plans to achieve set goals

The second-best outcome, Quadrant 2, results when the goal is met even though the plan is not followed (accidental success). In this case there may be an opportunity to learn from mistakes, based on what elements of the plan did and did not work. Because of the uncertainty of the planning process, it can be more important to learn from mistakes than to try to develop the perfect plan at the start (see the Honda motorcycle case example described in step 4 below).

Quadrant 3, where goals are not met even though plans are followed (planning failure), is troublesome because it suggests that the goal may be too challenging, and/or the organization lacks competence in developing and implementing appropriate plans. Such situations call for investing time and resources to confirm whether a particular goal is reasonable, and investing time and resources into developing a better plan. As in Quadrant 2, members should be especially open to changing the plan as they learn about better ways to do things. A classic example of planning failure is a sports team that follows the coach’s game plan but loses the game.

Quadrant 4, where goals are not met and plans are not followed (bungled attempt), is the worst quadrant. At best, this is an opportunity to learn from the experience and develop a new and improved plan. It may also be time to reconsider the original goal or to invest more resources or training in the goal-setting and planning processes.

Finally, in anticipation of step 4 in implementing strategy, it is important to note that whether or not a goal is met may be independent of whether the plans are followed. For example, achieving a goal to increase sales of home-based power generators by 50 percent may be met thanks to power outages in the region following a hurricane, and this may have little to do with whether the plan was to advertise in print media versus on television. At the same time, even the best plans to improve productivity will fail if a factory gets hit by a hurricane. In any case, it is helpful to treat the operational goals and plans developed in steps 1 and 2 as “living documents,” which means that they are open to being revised when they are revisited at regular intervals (e.g., every three months or less). This revisiting usually takes place within the workgroup but can also include stakeholders outside of the workgroup. It involves asking questions like: Do plans need to be revised in the face of contingencies? Are there unexpected events in organizational sub-units that need to be considered? Is there a danger of goal displacement occurring? In sum, goals and plans should be revised as appropriate. This brings us to the final step.

Test Your Knowledge

9.5. Step 4: Learn from the Strategy in Action

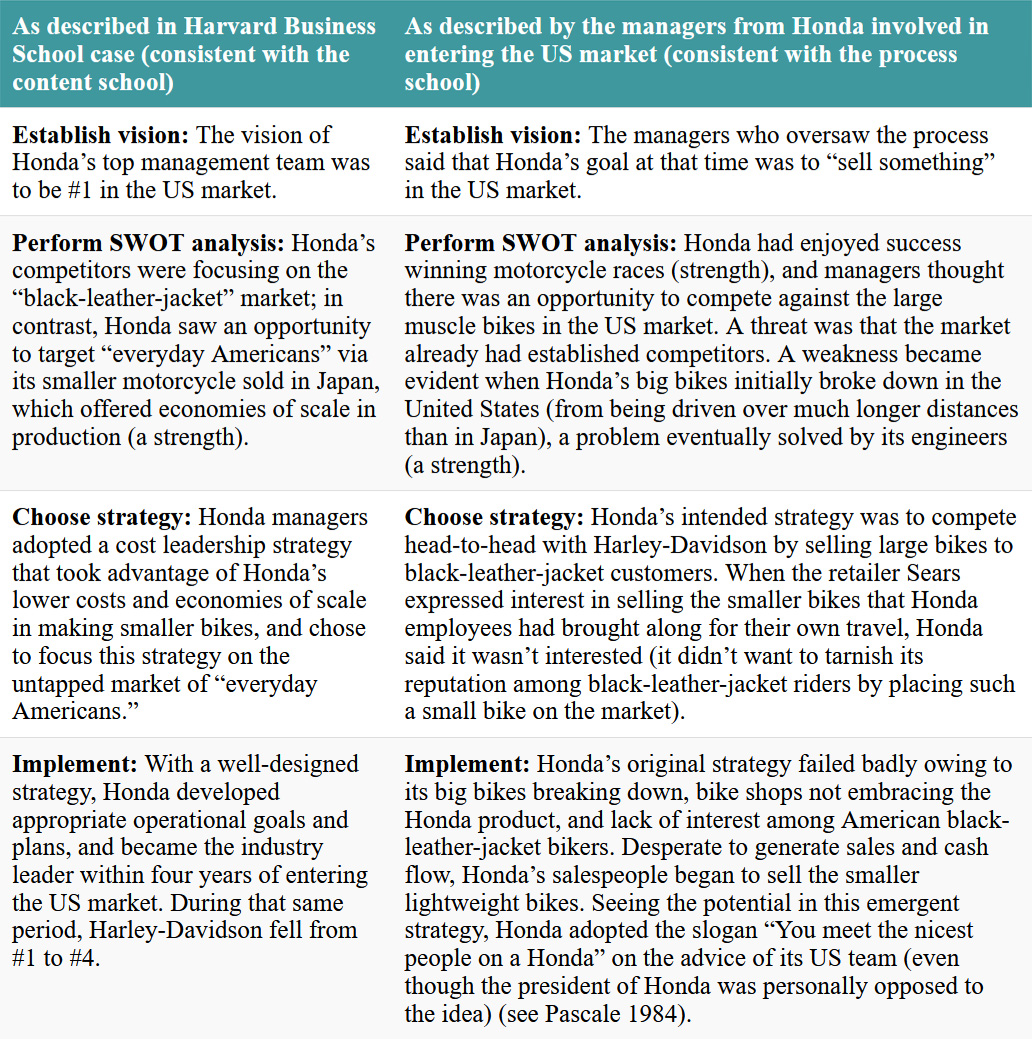

The final step in implementing strategy is to take the lessons learned while carrying out operational goals and plans and use them to fine-tune the goals and plans, and in particular to fine-tune or re-reformulate strategy as appropriate. Strategic learning refers to using insights from an organization’s actual strategy to improve its intended strategy. In order to understand the importance of strategic learning, it is helpful start with the example of a famous case study (published by the Harvard Business School) that described the successful entry of Honda motorcycles into the US market in the 1960s.[24] According to the case, Honda’s story confirms the importance of following the steps for formulating and implementing strategy as described thus far in Chapters 8 and 9. This description of how following these steps represents the recipe for success is shown in the left column of Table 9.5; we’ll get to the alternate interpretation shown in the right column in a bit.

Table 9.5. Case studies describing Honda’s success in the US motorcycle market

The lesson from the Harvard Business School case study of Honda’s success is that strategy makers who have a compelling vision, who perform a careful SWOT analysis, and who choose an appropriate generic strategy and then implement it will achieve competitive advantage and prosper. This version of Honda’s story is consistent with what has been called the content school approach to strategy. The content school emphasizes the rational-analytic, top-down, and linear aspects of strategy formulation. From a content school perspective, strategic management is a science that students can learn in business schools.

In contrast, the Honda managers who were actually involved in the case tell a very different story (see the right column in Table 9.5). The firsthand experiences of the managers are more consistent with the process school, which emphasizes that strategy formulation and implementation are ongoing and iterative, where one aspect influences the other. The lesson of the process school version of the Honda story—which differs sharply from that of the content school—is that success awaits managers who are able to learn from their mistakes and from unplanned ideas that emerge in the everyday operations of an organization. The process approach places much more emphasis on the art or craft of management rather than on the analytical science of management.[25] From a process school perspective, the most important work of strategic management is not mastering analytical tools to formulate a strategy (hallmarks of the content school) but rather developing skills in strategic learning, especially during the strategy implementation stage. The key to strategic management is learning from other stakeholders and identifying the emerging patterns in the “stream of actions” that make up organizational life.

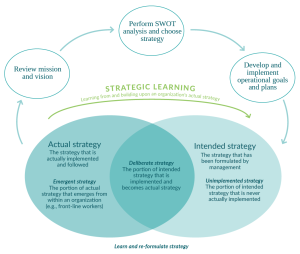

9.5.1. Strategy Implementation as Strategic Learning

The conceptual framework depicted in Figure 9.3 shows how strategic learning fits within the various steps of the strategy formulation and implementation process.[26] In order to understand strategic learning, it is important to recognize the difference between an organization’s intended strategy (what managers plan to do) and its actual strategy (the strategy that is actually implemented and followed). The content school focuses on the science of formulating well-supported, intended strategies, while the process school is more inclined to learn from actual strategies. The deliberate strategy refers to parts of the intended strategy that are implemented, whereas the unimplemented strategy refers to aspects of this intended strategy that never get put into practice. The deliberate strategy is only one part of an organization’s actual strategy. The other part is called the emergent strategy, which refers to actions taken by organizational members that were not anticipated at the outset by managers. The emergent strategy captures the idea that an organization’s actual strategy depends in part on the bottom-up actions of frontline organizational members, and on how they respond to other stakeholders in the implementation stage.[27] In the Honda example, the emergent strategy was to sell smaller lightweight bikes and target everyday Americans, ideas that Honda’s top management was initially opposed to (and to ideas that were foreign to other competitors in the US motorcycle market).

Figure 9.3. Strategy formulation and implementation, with focus on strategic learning

Strategic learning demands focusing on three things. First, managers must try to understand why some of their original intended strategy was not implemented. In the Honda example, this meant sending motorcycles back to Japan in order to improve the technology required for driving the longer distances that were common in the United States (and not common in Japan).

Second, managers need to identify elements of the (unintended) emergent strategy that have positive outcomes for the organization. Sometimes emergent strategies are very visible and hard to miss. Often, though, emergent strategies will be difficult to see simply because they are not expected. As illustrated by Honda’s slogan, “You meet the nicest people on a Honda,”[28] frequently the strategy will be formulated or initiated by frontline members and then subsequently approved by top managers. Organizational members further down the hierarchy often have a more direct knowledge of the issues at hand.

Third, managers must determine the implications of this analysis for the organization’s subsequent intended strategy. In particular, if the initial intended strategy is not working, then it is important to reconsider the information and assumptions underlying the original SWOT analysis. This may be difficult because it involves challenging assumptions and strongly held worldviews in an industry. For example, selling motorcycles to everyday Americans was hard to imagine in the 1960s until Honda did it, just as providing loans to impoverished Bangladeshi micropreneurs was inconceivable to banks in the 1970s until the Grameen Bank did it (see opening case, Chapter 6). From a process school perspective, strategic management is not like a brain that performs rational scientific analysis and then tells the rest of the members in the organizational body what to do. Rather, strategic management is more like a brain that is the focal point of the central nervous system and which listens to and learns from the (often unexpected) signals that it receives from throughout the organizational body. Thus, strategic managers are not smarter than other members in the organization. Rather, thanks to their unique position at the top of the organization, strategic managers have access to a comprehensive bundle of information that they must use responsibly.[29]

Taken together, this suggests that strategic management walks on two feet, one deliberate (content school) and the other emergent (process school).[30] Both the content and process schools are relevant for all three approaches to management, and there will be considerable variation in the relative emphasis each school is given within and among the three approaches. Even so, generally speaking FBL management tends to place greater emphasis on a deliberate top-down (content) approach,[31] and SET management tends to place greater emphasis on the emergent bottom-up (process) approach, and includes learning from members as well as from external stakeholders.[32] In contrast, TBL management seeks to balance a deliberate top-down approach with an emergent bottom-up approach, with a particular emphasis on learning from members lower down in the hierarchy.

Test Your Knowledge

9.6. Entrepreneurial Implications: Stakeholder Maps

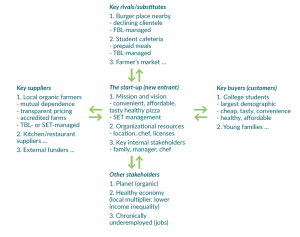

Entrepreneurs can use stakeholder maps to help manage the interplay between formulating and implementing strategies. A stakeholder map is a description of the organizational resources a new start-up has (and needs) to manage the key forces in its industry, and the key relationships it needs to establish and maintain. Recall that stakeholders are parties that have an interest in what an organization does because they contribute resources to the organization and/or are affected by its operations. A stakeholder map, as depicted in Figure 9.4, provides a helpful depiction of the key stakeholders that entrepreneurs need to keep in mind as they formulate, implement, and reformulate their strategy over time. We will look at each component of the map in turn, but first note that a distinct feature of the stakeholder map is the two-directional arrows connecting the start-up with its key stakeholders: suppliers, rivals, customers, and others. Just as stakeholders can and do exert force over a new entrant (represented by the heavier arrows in the figure), so also can new entrants influence external stakeholders (represented by the lighter arrows in the figure). This latter observation may be especially true when considering externalities where organizations may have a greater influence on stakeholders than vice versa. This bidirectional influence between a start-up and other stakeholders lies at the core of the dynamism and change that entrepreneurship offers society as it creates value. Note also that whereas FBL management presents this bidirectionality in competitive terms (i.e., as a power contest among stakeholders), SET management sees it in collaborative terms (i.e., as an opportunity to establish mutually beneficial relationships among stakeholders).

Figure 9.4. Dynamic stakeholder map for entrepreneurial strategic management

To help visualize and discuss what a stakeholder map might look like in practice, and how it can be used by entrepreneurs, Figure 9.5 provides a simple stakeholder map for a new pizza restaurant located adjacent to a university campus. In this example, the restaurant is the first in the neighborhood to offer pizza made from local and organic ingredients, and is being managed by entrepreneurs following a SET management approach. Even this simple description of the restaurant already helps to identify what industry it is operating in, what kinds of basic organizational resources it will need, and who might be its key stakeholders in terms of suppliers, rivals, customers, and others. Of course, the reverse is also true. Knowing what organizational resources and suppliers are available and identifying potential rivals and customers will influence an organization’s mission and vision statements.

Figure 9.5. Example of a simple stakeholder map for start-up pizza restaurant

9.6.1. How to Draw a Simple Stakeholder Map for a Start-up Organization

The place to start drawing a stakeholder map is in the central part of Figure 9.4, namely by describing the start-up’s mission and vision, organizational resources, and key internal stakeholders.

Mission and Vision

Developing its mission and vision statements helps a start-up to identify what value it will create,[33] what industry it will operate in, and what approach to management it will follow (FBL, TBL or SET) (see Chapter 8).[34] Mission and vision statements also provide the basis for developing the start-up’s value proposition. A value proposition is a statement of why a customer should choose the organization’s specific product or service. A value proposition explains what the organization does that is desired by the customer. Value propositions are often stated explicitly in a form that combines aspects of vision and mission statements as well as strategy. Toward this end, an organization might use a template like this one: “Our [product/service] helps [target customer] to [target’s need/goal] by [organizational contribution].”[35] For example, the value proposition of the new pizza restaurant described in Figure 9.5 might be: “Our organic pizza helps students get an affordable, tasty, healthy, and convenient meal that has been prepared in a socio-ecologically responsible manner.”

In any case, it is expected that the mission, vision, and value proposition may change and become more nuanced as the start-up unfolds and as entrepreneurs interact with and improve their knowledge about their key stakeholders. For example, Velo’s understanding of its value proposition became clearer as it discovered more about the sorts of clients it attracted, what sorts of employees were hired, and how the industry operated.

Organizational Resources

Entrepreneurs need to think deeply about and spell out what resources the organization needs, and they must identify a set of valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources (see Chapter 8). Does the organization have a novel idea or new patent that distinguishes it from existing organizations? Does it possess human resources with a particular or unique skill set? Does it have a particularly great location, or a noteworthy relationship with other organizations (e.g., exclusive distribution rights)? Does it enjoy tax advantages, or a funder with deep pockets? These resources should be listed and described.

In addition to identifying a start-up’s distinctive core competencies, entrepreneurs also need to identify the generic competencies required to operate in the industry. Many of these competencies will become clearer while analyzing an industry and its stakeholders, and after operations have begun and entrepreneurs learn about their actual strategy. For example, key core competencies for Velo are Nathaniel De Avila’s knowledge and ability to train others, and perhaps having employees who are willing and able to cycle to work. Access to other resources—like paintbrushes and hammers—is important and necessary but not part of Velo’s distinctive core competencies.

Furthermore, as new entrants in an industry, entrepreneurs need to become aware of the resources required to overcome barriers to entry. What licenses does the start-up need to operate in an industry? Are there regulations that limit what the entrepreneur can do? It is not unusual for entrepreneurs to start a new business, only to learn about the various regulations that they must comply with when they are well into the process. One entrepreneur likened starting a new organization to jumping into a pool with the goal of swimming to the other side, and halfway across being told he needs to tie weights to his legs and can swim with only one hand: “If I knew at the start what I found out six months in, I wouldn’t have jumped in in the first place.”[36]

Because SET entrepreneurs are more deliberately aware of and grounded in the larger community, they may become aware of regulatory and other barriers to entry earlier on. And because there are more stakeholders who benefit from SET start-ups (e.g., because SET management enhances socio-ecological externalities), there will be more people providing help and counsel. In contrast, FBL entrepreneurs have a narrower agenda—maximizing their own financial self-interests—and will likely get less support from the larger community. TBL entrepreneurs will be somewhere between the two.

In the example in Figure 9.5, the pizza restaurant needs all the facilities and resources associated with any restaurant: a physical location, a properly outfitted kitchen, an eating area with furniture and dishes and cutlery, kitchen staff who prepare the food, staff who serve the food, a manager who can administer the business, and so on. Key resources for the restaurant include its excellent location (next to campus) and a chef with training and experience in baking organic pizzas.

Internal Stakeholders

In addition to recognizing the key resources in the firm, entrepreneurs must also be aware of the internal stakeholders who control those resources. The most important internal stakeholders are the entrepreneurs themselves. In start-ups by a lone entrepreneur, it is helpful for the entrepreneur to reflect on what she or he wants out of the new venture, both personally and professionally (see Chapters 1, 5, 6). The same is true when a new venture is led by a group of entrepreneurs or by a family. Members should sit down and discuss with each other what they want, and also how they will handle disagreements. One of the founding owners at Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company said that this was the most valuable piece of advice she received when the firm was being started, and that having a plan for handling disagreements and conflict allowed the firm to take bolder decisions in the direction of SET practices, because owners knew they could resolve conflicts that might arise.[37]

Other key internal stakeholders are staff with distinctive and strategic competencies. Especially when those skills are indispensable to the operation of the organization, entrepreneurs should begin to establish training or succession plans so that if the key stakeholder suddenly leaves, they can be replaced. For example, at Westward Industries (opening case, Chapter 18), a craftsman whose skills were deemed indispensable for building the firm’s main product was reluctant to teach others how to do his job, because he knew this would decrease his power within the firm. However, managers convinced him to train others, and when he later suffered a heart attack the firm was able to continue operate smoothly.[38] Often the key competencies and internal resources are provided by entrepreneur(s), but for some skills they may be dependent on employees. What are the contingency plans if these key members leave the organization?

In our example in Figure 9.5, the pizza restaurant is a family firm, and so family members are key internal stakeholders. This includes members who are actively involved in the start-up (one parent and the oldest offspring) but also includes members who are passively involved (siblings who know that their inheritance will be affected by how the restaurant performs). In this case the oldest offspring is the only one with previous experience managing a restaurant, and thus she is a particularly important stakeholder. And the chef, a non-family member, is a key stakeholder because if he leaves, the restaurant could flounder. He is one of two chefs in the community with experience and education in organic pizza making.

Once the start-up’s mission and vision, organizational resources, and key internal stakeholders have been described, the other components on the stakeholder map can be filled in, starting with suppliers.

Suppliers

New ventures obviously can’t create everything on their own, so they need to buy inputs from others (Chapter 7). It is valuable for entrepreneurs to list all the supplies they require and identify potential suppliers who can meet those requirements. They should be aware of each supplier’s relative power, price offerings, reputation, and approach to management (it is often easier to deal with suppliers who have the same approach as the entrepreneurs).

Establishing relationships with suppliers can be more challenging than it might first appear. Potential suppliers may perceive a new start-up to be risky and be hesitant to sell it supplies, wondering if they will ever get repaid. Or suppliers may be hesitant if they believe a new start-up might tarnish their reputation. For example, a high-quality brand would not want to supply a dollar store. Moreover, since new ventures typically order relatively low quantities of goods from suppliers, they are not likely to be able to negotiate for low prices or special deals. Especially important suppliers are banks that supply start-up loans and ongoing lines of credit. Often a well-developed business plan can help entrepreneurs to gain the confidence of banks and other suppliers (Chapter 6).

How entrepreneurs think about and manage suppliers varies by management approach. FBL entrepreneurs think of suppliers in financial terms, expressed colloquially as “buy low, sell high.” This puts start-ups at a disadvantage against large incumbents like Walmart, with its huge purchasing power and economies of scale. But FBL entrepreneurs have several strategies they can adopt. They could sell goods whose sales volume is lower than what would be carried by large competitors (e.g., custom goods in a niche market, focusing on the long tail of the market described in Chapter 6). Or, they could buy from suppliers whose quality and safety standards are not acceptable to large FBL competitors. They could purchase raw materials and component parts from low-priced overseas factories that have questionable labor and safety practices, and sell them at a dollar store. Or they could offer services by outsourcing jobs to underpaid service providers (e.g., Uber drivers, staff in some inexpensive restaurants). Of course, some of these strategies would be unacceptable to TBL and SET entrepreneurs.

TBL entrepreneurs may be able to find opportunities to compete with incumbents by choosing suppliers that help the start-up to offer customers a value proposition that they are willing to pay extra for. This was the genius behind the growth of Whole Foods, which Amazon bought in 2017 for US$13 billion as part of Amazon’s own intrapreneurial foray into the food industry.[39] Whole Foods enjoyed a competitive advantage over conventional supermarkets by developing a supplier network that enabled it to sell organic foods. Now that organic foods have become mainstream, this window of opportunity is closed for future entrepreneurs, but there may still be an opportunity for a “100-mile grocery store” that sells local and organic groceries. TBL entrepreneurs have an incentive to find and develop suppliers who will help them achieve a positive reputation. For example, in order to ensure that their suppliers’ employees are paid a living wage and do not work with toxic chemicals, companies like Starbucks help coffee growers to create fair trade co-operatives, and companies like Walmart create incentives for suppliers to provide organic cotton or foods.

Both FBL and TBL entrepreneurs seek to have power over suppliers, but SET entrepreneurs are open to being influenced by suppliers and other stakeholders. Moreover, the definition of a supplier encompasses a wider scope for the SET entrepreneur than it does for the other two approaches. In addition to direct suppliers of inputs, SET entrepreneurs pay attention to socio-ecological externalities associated with a supplier’s suppliers. For example, rather than purchase fair trade goods from a wholesaler, Ten Thousand Villages has sought to purchase directly from producers because this helps to establish a direct relationship valued by consumers.[40]

In our example in Figure 9.5, local organic farmers are key suppliers for the pizza restaurant. It may be a challenge to find all the suppliers for all of the ingredients a chef wants. It is especially important to establish and maintain ties with one-of-a-kind suppliers of specialty items, for example, a firm that makes sausages with local herbs and spices and grass-fed beef. The key is to ensure that both parties are satisfied, which includes setting a price that is fair to both. Ideally farmers will be accredited as organic by an accreditation agency. The pizza restaurant might decide to help pay for such accreditation if that opens up access to supplies that it needs. Sometimes suppliers cannot be found, and the company will need to make a product it intended to buy (e.g., when Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company purchased its own flour mill, Chapter 7). Other times the lack of suppliers may be the mother of invention, such as when lack of a local supplier of yeast might result in a pizza restaurant serving sourdough crust, and this becomes an unexpected treat and health benefit for customers.

Rivals (Competitors)

Finally, entrepreneurs need to be very aware of their rivals (which could be seen as competitors or as collaborators). Rivals set constraints on what entrepreneurs can and cannot do. For example, entrepreneurs must consider rivals’ prices and product lines when choosing their own organization’s prices and product lines. The FBL approach assesses such constraints in financial terms. Because the FBL approach assumes a win-or-lose competition for relatively scarce customer dollars, managers need to keep up with competitors. If other organizations release new or improved products and services, the FBL entrepreneur must find a way to respond.

Similar dynamics are at work in TBL firms that do not welcome new competitors into their trading areas and who take advantage of their own strengths to defeat them. Walmart can charge its customers lower prices than its competitors can because thanks to its huge purchasing power, Walmart can demand lower prices from suppliers.[41] Indeed, Walmart has been accused of entering geographic trading areas and driving its pre-existing smaller local competitors out of business.[42]

By their nature, SET entrepreneurs often do not compete directly with FBL and TBL firms. Rather, SET entrepreneurs offer a different value proposition. If a SET entrepreneur sells coffee and chocolate, it is likely to be fair trade and organically grown. And in contrast to TBL firms like Walmart, in SET firms the retail employees are more likely to be paid a living wage. If you live in Garden Hill First Nation, you can buy chicken at the Northern Store or at Meechim Inc., but the latter product is raised locally and provides much-needed jobs in the community. In this sense SET organizations are clearly different from their FBL and TBL competitors. Moreover, SET entrepreneurs do not like the language of competition, preferring to think of organizations similar to them as collaborators rather than as competitors.[43]

In our example in Figure 9.5, the pizza restaurant may find that it is perceived to be a competitor by the hamburger restaurant next door. Because the sales at the burger place are declining, the pizza place may expect fierce price competition. The on-campus cafeteria, which is closer to students’ dorm rooms and offers the convenience of prepaid meals, may be another potential competitor. In light of this, the pizza restaurant may offer similar “meal cards,” where students can show their student card and purchase eleven meals for the price of ten. After the restaurant is in business for a while, it may realize that an alternative is the grocery store down the street selling frozen pizza, which students and young families purchase and bake at home. In response, the pizza restaurant may offer its own healthier frozen pizzas and even consider becoming a supplier for the grocery chain.

Buyers (Customers)

Paying customers are essential to business organizations because they provide the revenues needed to pay salaries to members, to purchase inputs from suppliers, and to provide financial returns to owners. In non-business organizations, other terms are used in place of “customers.” For example, soup kitchens have patrons, hospitals have patients, and schools have students. But whatever you call them, customers are the focal point of an organization’s product and service outputs.

Customers are key stakeholders for a start-up, and entrepreneurs should think deeply about their customers. First, entrepreneurs must decide which customers to target, and what their wants and needs are (see Chapter 6). Customers clearly have a lot of power over start-ups, but entrepreneurs also have opportunities to influence customers.

Entrepreneurs obviously want customers to choose their product or service. FBL entrepreneurs are primarily concerned with customers as a source of revenue, and tend to assume that customers are primarily concerned about their own economic well-being. Therefore, FBL entrepreneurs focus on convincing customers that their start-up is offering products or services that satisfy the customer’s desires in the most convenient and affordable way.

The TBL approach is similar but distinguishes itself by emphasizing how products and services simultaneously satisfy customer desires and reduce negative socio-ecological externalities. For example, many consumers choose to shop at Whole Foods and willingly pay higher prices because it sells organic groceries and promises to pay employees a living wage.

SET entrepreneurs also need customer support, but take a somewhat different approach to developing it.[44] In particular, SET entrepreneurs emphasize building relationships, often inviting customers to be involved in the design of goods and services. Likewise, the prices in a SET firm are not set to simply maximize profit. SET entrepreneurs want to enhance global social and ecological well-being, and assume that customers do as well. For example, when talking to potential clients, Velo encourages then to reuse existing materials if possible and to choose new materials that are sustainable. This sometimes means decreasing its own profits, and sometimes means not accepting profitable work that it considers inadvisable. Rather than win customers through conventional marketing or offering the lowest price, SET-managed organizations attract like-minded customers with their reputation for ethical conduct and social responsibility.

In our example in Figure 9.5, the pizza restaurant has chosen to target university students, taking advantage of its location next to campus. In order to understand this target market, the entrepreneurs did some surveys and taste tests at sporting events on campus. They learned that students want affordable and fast food, and are open to but not very aware of the benefits of local and organic food. So the entrepreneurs decided to offer “fact sheets” at the restaurant and on the company website, and even painted some “Did you know that . . . ?” statements on the restaurant walls to educate customers and try to increase their loyalty. Over time it might emerge that the restaurant is also popular with young families, and so the restaurant might include a special kids’ menu and offer coloring books featuring scenes from local farms that supply the ingredients.

Other Stakeholders

Finally, the stakeholder map in Figure 9.4 explicitly identifies other stakeholders associated with an organization’s financial, social, and ecological externalities (see Chapters 3, 4 and 5). For example, does the organization pay a living wage so that its employees’ families can have adequate food, shelter, and education? What about its GHG emissions and those of its suppliers? Do its practices contribute to increasing income inequality?

As discussed throughout the book, FBL management typically does not focus on externalities because, by definition, they are external to an organization’s operations. TBL managers are likely to address negative externalities if doing so can improve the firm’s profits. Thus, a TBL manager is happy to take better care of the planet (a key stakeholder) by using solar power if doing so also enhances the financial bottom line. Or, TBL managers will make jobs less stressful and thereby also reduce stress among employees’ children (an external stakeholder), if doing so also reduces the firm’s financial costs related to turnover and absenteeism.[45] Finally, SET management is more deliberate in considering external stakeholders and trying to enhance socio-ecological well-being, even if this does not enhance profits. This is evident, for example, when firms make anonymous donations to agencies serving the marginalized.

Both TBL and SET entrepreneurs recognize that working with stakeholders to address socio-ecological externalities provides their start-ups with increased social legitimacy. Indeed, SET firms often include positions on their boards for members of groups like non-governmental organizations. A non-governmental organization (NGO) is a non-profit organization whose primary mission is to model and advocate for social, cultural, legal, or environmental change. Along similar lines, when TBL fast-food giant McDonald’s was facing heavy criticism for using packaging that had a lot of negative ecological externalities, it formed a task force with an NGO called Environmental Defense Fund, and together they worked to develop a forty-two-step waste-reduction plan.[46] NGOs that work together with businesses in this way can help to increase socio-ecologically responsible choices available to customers, and businesses can benefit from the counsel and credibility of the NGOs.

In the example in Figure 9.5, the pizza restaurant is deliberately benefiting at least three different external stakeholders. First, by using only local and organic ingredients, the restaurant is helping the planet (organic practices restore carbon to the soil). The restaurant also benefits the planet by composting its waste and using low-energy LED lighting. Second, sourcing its ingredients locally helps the local economy (local multiplier effect) and may help to reduce income inequality (the restaurant and its suppliers are not part of large chains). Third, in cooperating with a local NGO that helps to find jobs and training for chronically underemployed people, the pizza restaurant serves to benefit to that group.

Map Dynamics

A key feature of the stakeholder map is that it is relevant for both strategy formulation and implementation, with its bidirectional arrows helping to see how a strategy emerges over time. As illustrated by our example in Figure 9.5, the inability to find a supplier can change an organization’s value proposition or product line (e.g., inability to find a local yeast supplier may prompt the idea of sourdough crust pizza), insights about rivals and substitutes can create a new distribution channel (e.g., the idea to offer frozen organic pizza), observing customers can change delivery (e.g., kids’ menu, meal cards), and awareness of externalities can benefit stakeholders who are suffering (e.g., the planet). It is when the relationships with stakeholders are put into practice that strategic learning can begin. And it is at this time that entrepreneurs have positive (or negative) influences on key stakeholders, such as increasing the size of the market for organic farmers’ goods, getting college students to eat healthier food, providing new options for grocery stores, hastening the demise of unhealthy fast-food restaurants, and providing jobs for the chronically underemployed.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- The four steps of the strategy implementation process are (a) developing operational goals, (b) developing operational plans, (c) implementing and monitoring the goals and plans, and (d) engaging in strategic learning.

- With regards to making operational goals:

- FBL managers focus on SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, results based, and time specific).

- SET managers focus on SMART 2.0 goals (significant, meaningful, agreed upon, relevant and timely).

- Operational plans range from single-use to standing plans. FBL plans tend to be developed by managers and ignore externalities, while the development of SET plans tends to involve all stakeholders and consider externalities.

- When it comes to making operational plans—both single-use and standing—all three management approaches consider the following five factors:

- exactly what steps and actions are necessary to meet the goal(s),

- possible constraints that may make it difficult to put the plan into action,

- resources that are necessary to perform the activities,

- availability of required resources, and

- the order, timing, and milestones for each action to be performed.

- When put into practice, (a) plans may or may not be followed, (b) goals may or may not be met, and (c) scripts may or may not help to develop subsequent goals and plans that enhance performance.

- With regard to strategic learning:

- FBL management emphasizes top-down deliberate strategy, the content school, and sees strategic management as analytical science.

- SET management emphasizes bottom-up emergent strategy, the process school, and sees strategic management as a craft.

- Stakeholder mapping can help managers to consider the transfer of resources and interplay among key stakeholders over time.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Identify the four steps in implementing strategy. What are the key differences in the content, orientation, and process of the steps from FBL, TBL, and SET perspectives?

- From an FBL perspective, which of the four steps of implementing strategy do you think is the most challenging? Answer the same question from a TBL and from a SET perspective. Are there differences in your answers for the three types of management? Explain.

- What are the key similarities and differences between SMART goals and SMART 2.0 goals?

- Do you think that developing operational plans plays a more central role in the FBL, the TBL, or in the SET approach? Which approach is most difficult to put into practice? Explain your answer.

- Briefly describe the differences between the content and process school analyses of how Honda motorcycles became #1 in the US market. The process school description, which is based on interviews with the managers involved, may be the more accurate portrayal of what actually happened, but do you think the content school description is more valuable for teaching purposes? Put differently, if Honda had completed the SWOT analyses and had chosen the correct strategy prior to entering the United States (as consistent with the content school approach), then it could have saved a lot of time and money and avoided floundering around after it arrived. However, perhaps doing the rational analysis up front would not have resulted in the successful strategy it eventually developed, and perhaps the real key to Honda’s success was that managers engaged in strategic learning during times of floundering. Which approach do you think should be taught in business schools? Defend your answer. Would it be better to teach that one approach, or to teach both?

- Complete a stakeholder map for an organization you would like to start up.

- Based on a series of over twenty interviews with members of Velo Renovation as part of a larger SET research program undertaken by Bruno Dyck and his colleagues at the Asper School of Business of the University of Manitoba. ↵

- Dyck, B. (1997). Understanding configuration and transformation through a multiple rationalities approach. Journal of Management Studies, 34: 793–823. See also Flyvbjerg, B., & Gardner, D. (2023). How big things get done: The surprising factors that determine the fate of every project, from home renovations to space exploration and everything in between. Crown Currency. ↵

- Page 132 in Locke, E. A. (2004). Linking goals to monetary incentives. Academy of Management Executive, 18(4): 130–133. ↵

- Shaw, K. N. (2004). Changing the goal-setting process at Microsoft. Academy of Management Executive, 18(4): 139–142. ↵

- Shaw (2004). For examples of setting SMART goals, see Sumar, S. (2024, July 18). SMART goals for HR professionals—A quick review with examples. Vantage Circle. https://www.vantagecircle.com/en/blog/smart-goals-for-hr-professionals/ ↵

- Latham, G. P. (2004). The motivational benefits of goal-setting. Academy of Management Executive, 18(4): 126–129. ↵

- Wei, X., & Zhu, L. (2024). Developing a project-expectancy inventory for the construction industry from the owner’s perspective. Sustainability, 16(7): 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072675 ↵

- Gary Latham uses the example of independent loggers working in the southern United States, where pulpwood crew supervisors used goal-setting theory to give workers specific high-production goals and provided tally meters so that the loggers could count the number of trees that they cut down. Productivity soared due to “the psychological outcomes of setting and attaining high goals include enhanced task interest, pride in performance, a heightened sense of personal effectiveness, and, in most cases, many practical life benefits such as better jobs and higher pay.” Note that there was no productivity change among loggers who were simply told to do their best (i.e., not given a SMART goal) (Latham, 2004: 126). ↵

- Example and quotes taken from Shaw (2004: 139). Note that we follow Shaw (2004) in our use of the acronym SMART, where “R” refers to “results-based.” In other presentations of SMART the “R” refers to relevance. See for example Ebert, R. J., Griffin, R. W., Starke, F. A., & Dracopoulos, G. (2015). Business essentials (8th Canadian ed). Pearson. ↵

- Locke (2004). ↵

- Latham (2004). ↵

- Wright, P. M., George, J. M., Farnsworth, S. R., & McMahan, G. C. (1993). Productivity and extra-role behavior: The effects of goals and incentives on spontaneous helping. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(3): 374–381. ↵

- Upshaw, T. (2021, September 17). Your CSR strategy needs to be goal driven, achievable, and authentic. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/09/your-csr-strategy-needs-to-be-goal-driven-achievable-and-authentic ↵

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30: 91–127. ↵

- Latham (2004: 129). Sockbeson, C. E. S., Hartman, L. R., & Shaw, J. C. (2023). Lessons from The Office: Mismanaged motivation. Management Teaching Review, 9(4):382–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298123116329 ↵

- Koukoumpliakos, I., Giannarakis, G., Sdrolias, L., Kalogiannidis, S., & Syndoukas, D. (2024). Stressing corporate social responsibility for business sustainability: Empirical analysis of CSR practices, motivations and growth impacts in post-crisis Greece. Journal of System and Management Sciences, 14(7): 301–325. For example, managers at Reell Precision Manufacturing are committed to “do what is right, even when it does not seem profitable, expedient, or conventional.” See page 137 in Benefiel, M. (2005). Soul at work: Spiritual leadership in organization. New York: Seabury Books. ↵

- See the Eliza Jennings website: https://elizajennings.org/about. See also Wong-Ming Ji, D. J., & Neubert, M. J. (2001). Voices in visioning: Multiple stakeholder participation in strategic visioning [Presentation]. Academy of Management Meetings, Washington, DC. ↵

- For more on Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company, see Vagianos, S. (2022). Social and ecological thought: A case study of Tall Grass Prairie Bread Co. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba. See also the documentary by Ridley, N. (director). (2024, June 12). Beyond profit: Seeking sustainability. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzkn9Mm1X84 ↵

- Gunster, S. (2017). This changes everything: Capitalism vs the climate, by N. Klein [Book review]. Environmental Communication, 11(1): 136–138. ↵

- Shourkaei, M. M., & Dyck., B. (2023). Making sense of “growth” in post-growth businesses: An empirical study [Working paper]. University of Manitoba. ↵

- Ekengren, M. (2024). Why are we surprised by extreme weather, pandemics and migration crises when we know they will happen? Exploring the added value of contingency thinking. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 32(1): e12515. ↵

- And with this increased emphasis on emergence, some have argued that this requires goals from a SET approach to be more innovative: Neugebauer, F., Figge, F., & Hahn, T. (2016). Planned or emergent strategy making? Exploring the formation of corporate sustainability strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(5): 323–336. See also differences in the three approaches related to the development of business plans, described in Chapter 6. ↵

- Pauls, K. (2023, August 27). A centuries-old bean is making a comeback in the form of vegan ice cream. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/lupin-bean-plant-based-foods-1.6945048 ↵

- Adapted from Pascale, R. T. (1984). Perspectives on strategy: The real story behind Honda’s success. California Management Review, 26: 47–72. Pascale does not cite Harvard Business Review case but cites the report it drew from: Boston Consulting Group (1975, July 30). Strategic Alternatives for the British Motorcycle Industry. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London. For a more recent article on the pros and cons of whether firms entering in an established industry should (a) compete directly with industry leaders, or (b) offer alternative products, see Chen, Y., & Sun, S. L. (2023). Leapfrogging and partial recapitulation as latecomer strategies. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(3): 100099. ↵

- Mintzberg, H. (1987). Crafting strategy. Harvard Business Review, July–August: 66–75. For a more recent article that describes how strategy is crafted in four different types of organizations (foreshadowing Chapter 11 on organization design), see Mintzberg, H. (2024). Four forms that fit most organizations. California Management Review, 66(2): 30–43. ↵

- This figure is adapted from Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate, and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6: 257–272. ↵

- For a discussion of ten activities that middle managers engage in to: (a) implement intended strategies, and (b) implement unintended strategies, see Christie, A., & Tippmann, E. (2024). Intended or unintended strategy? The activities of middle managers in strategy implementation. Long Range Planning, 57(1): 102410. ↵

- The slogan was developed by a marketing student for an assignment. ↵

- This is the kind of “brain” described by Durkheim, E. (1958). Professional ethics and civic morals (C. Brookfield, Trans.). Free Press. Extending this metaphor even further, an FBL approach is akin to the brain deciding that the body should run a marathon and then is surprised when the body is unable. A TBL/SET approach is more sensitive to the needs and capacity of the body and to developing them appropriately, before running any marathon. ↵

- “Our conclusion is that strategy formation walks on two feet, one deliberate, the other emergent” (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985: 271). ↵

- For a series of articles characterizing the debate between the process school and the design school, see Mintzberg, H., Pascale, R., Goold, M., and Rumelt, R. (1996). The “Honda Effect” Revisited. California Management Review, 38(4): 78–117. These include Mintzberg, H. Introduction (pp. 78–79); Mintzberg, H. Learning 1, Planning 0 (pp. 92–93); Goold, M. Design, learning and planning: A further observation on the design school debate (pp. 94–95); Mintzberg, H. Reply to Michael Goold (pp. 96–99); Goold, M. Learning, planning, and strategy: Extra time (pp. 100–102); Rumelt, R. P. The many faces of Honda (pp. 103–111); Pascale, R. T. Reflection on Honda (pp. 112–117). For a more recent take on process vs. content schools, see Takagi, T., & Takahashi, M. (2023). Rationality bias of strategy theory: Strategy as leverage of local institutions. The Journal of Organization and Discourse, 3: 20–25. ↵

- See empirical data reported in Dyck, B. (2007). Competing rationalities in management practice and management education [Presentation]. Academy of Management, Philadelphia. See also Dyck, B. (2020). The integral common good: Implications for Mele’s seven key practices of humanistic management. Humanistic Management Journal, 5(1): 7–23. ↵

- The distinction between creating value and capturing value is an important consideration. Capturing value potentially can be done without creating much new value, as illustrated by a hypothetical entrepreneur stealing the market share of a competitor’s cash cow, or by the quadrillion-dollar global derivatives market. ↵

- Because of their different priorities, SET entrepreneurs likely have more opportunities available to them. One does not have to look very hard to identify significant social or ecological problems, and any of these problems can be the basis of a SET or TBL entrepreneurial start-up, which can adopt a minimizer strategy that improves on current FBL methods to reduce externalities, or a transformer strategy that taps a previously overlooked resource to create positive outcomes. SET entrepreneurs in particular do not need to worry maximizing financial well-being; they only need to make enough money to operate sustainably. ↵