Part 1: Background and Basics

6. Entrepreneurship

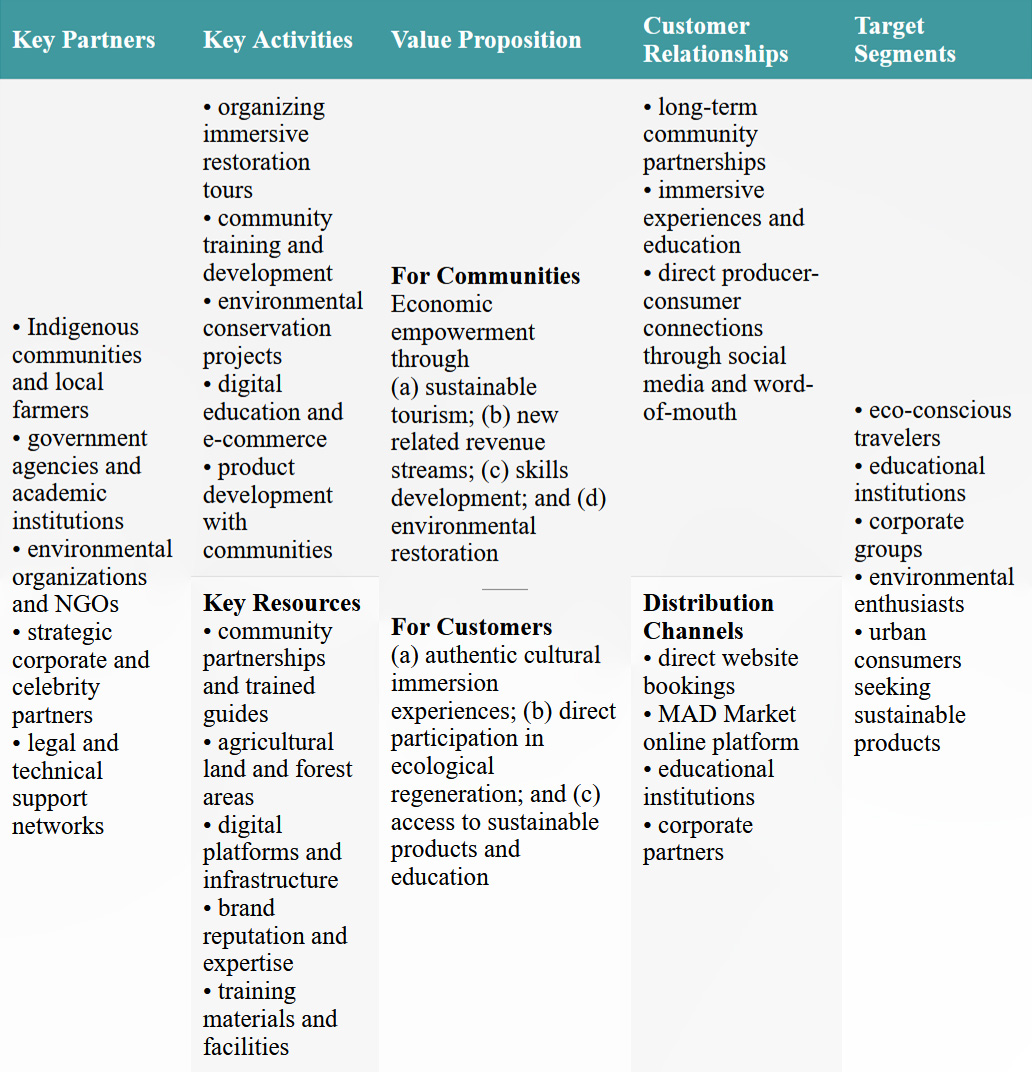

Chapter 6 provides an overview of the benefits of entrepreneurship and the four steps of the entrepreneurial process as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify contributions entrepreneurs make to society.

- Explain how entrepreneurship is similar to and different from running a family business and a small business.

- Describe the four main steps in the entrepreneurial process and explain its cyclical nature.

- Identify and describe the elements of a business plan and of an Entrepreneurial Start-Up Plan.

6.0. Opening Case. MAD Travel: Making a Difference Through Sustainable Tourism

In 2015, Rafael Ignacio S. Dionisio, then in his twenties, stood at the edge of a barren landscape in Zambales, Philippines, surveying what was once lush forestland.[1] The scene before him represented both a challenge and an opportunity. The degraded land belonged to the Indigenous Aeta community, which had struggled for generations with poverty and food insecurity. However, where others saw desolation, Dionisio envisioned a transformed landscape, one where sustainable tourism could fund reforestation efforts while providing economic opportunities for the marginalized Aeta people.

This vision would eventually become MAD (Make A Difference) Travel, a social enterprise that would demonstrate how tourism could serve as a vehicle for environmental conservation and community development. However, like many entrepreneurial journeys, the path from idea to impact was neither straight nor simple.

The entrepreneurial opportunity became clearer when Dionisio began working closely with the Aeta community in Zambales. He observed that while the area had immense potential for tourism, traditional tourism models often excluded Indigenous communities from meaningful economic participation while contributing to environmental degradation. This insight led to the development of MAD Travel’s innovative approach: immersive restoration tours that would engage visitors in community culture, tree planting, and environmental conservation.

To test his concept, Dionisio started small, organizing pilot tours that brought visitors to the Aeta community. These initial experiments revealed both challenges and opportunities. While visitors were deeply moved by the experience and eager to contribute to reforestation efforts, the logistics of managing tours in remote areas while ensuring consistent quality and community benefit required careful planning. The pilot phase also highlighted the need for comprehensive community training in hospitality, tour guiding, and sustainable agriculture.

Perhaps the most important thing Dionisio demonstrated during the pilot testing was the importance of listening to and learning from Indigenous communities, which lies at the heart of transformation and reconciliation. Dionisio was moved when, after the first tour had visited an Indigenous community, the chieftain rejected the money (the equivalent of about two months’ earnings) Dionisio wanted to pay for hosting the tour.

And he said something I’ll never forget. He said: “Look at our ancestral domain. It’s 3,000 hectares, but it’s empty. If you give me money I might spend it on cellphone credits, I might spend it on three-in-one coffee, or I might spend it on cigarettes which the men like. And that’s not sustainable. No one will benefit in the long term.”

So, I asked, “What do you want? Because I have to give you something. We’re business partners and I brought too many people [to visit you] not to pay you anything.” And he said: “Well, if you’re coming back maybe you can bring seeds because our land is empty. If you bring seeds, even if someone steals it, they’re still going to plant it, and my kids and grandkids can still benefit from that growth.” And so, I was really moved by this guy who finished only fourth grade and was really thinking about long-term sustainability over money in the short-term. . . .

We found that we really had to listen to their dreams, and make their dreams ours, before they decided to help us in our dreams. So, it was not us walking in and saying: “Oh, you need this, you need that.” It was us walking in, listening to them, and then together we say, “Maybe we can work on this together.” And that’s what we did. So, we used this as a model and the plan expanded.[2]

Building on these experiences, Dionisio developed a comprehensive plan that went beyond simple tourism. MAD Travel would create multiple revenue streams for communities through tourism, product development, and agroforestry. The plan included training fifty-two families in Yangil, Zambales, in various aspects of ecotourism and sustainable agriculture. A particular focus was placed on the Kasuy ng Kababaihan project, which would eventually plant 20,000 cashew trees, providing a sustainable income source for local women.

Acting on this plan required mobilizing resources and building further partnerships. Dionisio worked to secure support from various stakeholders, including the Department of Tourism, local government units, and environmental organizations. He also developed innovative funding mechanisms, such as tree-planting gift cards and digital courses on social enterprise and design thinking, to sustain the initiative’s growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to the tourism-based model, but it also sparked innovation. MAD Travel pivoted to launch new initiatives like MAD Market, an online platform connecting urban consumers with Indigenous producers, and MAD Courses, providing online education on social enterprise and sustainability.[3] In a compelling interview on Our Awesome Planet, Dionisio shared the story behind MAD Market’s creation and its mission to make a difference through everyday groceries. The podcast reveals how MAD Market became more than just a pandemic pivot—it evolved into a powerful platform for redistributing wealth and value to local farmers, communities, and small businesses across the Philippines. Through this initiative, simple acts like weekly grocery shopping became opportunities for meaningful social impact, allowing urban consumers to support vulnerable sectors while staying safe at home during the lockdown.

The Story of MAD (Making a Difference). Source: https://www.youtube.com/live/NxLkgrJPEVI?si=pToZXSzbk8WtnI-P

6.1. Introduction

While the rest of this book focuses on management issues that are relevant to any type of existing organization, this chapter starts with a brief description of entrepreneurial start-ups, including small and family-run organizations. We then focus on the four-step entrepreneurial process for creating new organizations. This includes the development of business plans and Entrepreneurial Start-Up Plans (ESUPs), which serve to introduce some key content found in the rest of the book. As always, we contrast and compare implications for different approaches to management: Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET).

6.2. The Importance of Entrepreneurship

Recall from Chapter 1 that an entrepreneur is someone who conceives of new or improved goods or services and exhibits the initiative to develop that idea by making plans and mobilizing the necessary resources to convert the idea into reality. The most familiar type of entrepreneurs, and the focus of this chapter, are so-called classic entrepreneurs— those who start new organizations to pursue their ideas.[4]

Almost every organization you know of (e.g., Tesla, Microsoft, FedEx, and the pizza place down the street) had an entrepreneurial beginning, and such new organizations are vitally important, especially in terms of creating new jobs. For example, over the past forty years in the United States, new organizations have created an average of three million jobs per year, while existing firms have actually reduced the number of jobs by an average of one million jobs per year.[5] In other words, the only reason that the United States has had job growth in the past forty years is because classic entrepreneurs were creating new jobs at a faster rate than existing firms were eliminating them through downsizing and offshoring. The same pattern has been observed all over the world: new businesses are the source of most new jobs.[6]

Entrepreneurial start-ups are also important for the innovations they provide to society. Research shows that as organizations grow older, they are less likely to develop innovative solutions.[7] Radical new solutions are more likely to come from new organizations. In fact, more than half of all innovations—and 95 percent of radical, industry-changing innovations—have come from entrepreneurs.[8] This phenomenon of new entrepreneurial organizations leading the way for older ones may help to explain why young people feel drawn toward entrepreneurship. In a 2014 survey, 70 percent of millennials reported that they expected to work independently to create something new during their careers.[9] Even though entrepreneurs are important sources of innovation, most replicate existing goods and services, using known process and technology.[10]

6.2.1. Entrepreneurship and Small Business

The terms “entrepreneur” and “small business manager” are often used interchangeably, because most entrepreneurs are also small business managers. Nonetheless, some entrepreneurs manage large businesses (e.g., Tesla, Grameen Bank), and not all small business managers are entrepreneurs (e.g., the manager of the local hardware store who inherited it from their parents may not be an entrepreneur). Entrepreneurial organizations are distinguished by doing something new (including replicating an existing service but for a new region or clientele), whereas small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are defined by their size, not by whether they have launched something new. Many criteria can be used to judge an organization’s size (e.g., revenue, assets, ownership structure), but the most commonly used criterion is the number of employees. Governments such as those in Canada, the United States, and the European Union define a small organization as one with fewer than 100 employees, and a medium-sized organization as having from 100 to 500 employees.

Because of their size, SMEs differ from large organizations in important ways. For one, SMEs have smaller budgets, so their fixed costs of operation tend to be relatively large and thus a greater burden. Fixed costs are business expenses that do not vary with the quantity of organizational output (e.g., the rent payments for a coffee shop are the same, no matter how much coffee it sells). As well, SMEs have fewer resources to compete with other organizations, such as high wages and promotion packages to offer employees, or large marketing budgets to attract customers. In addition, SME operations often are not large enough to benefit from economies of scale. Economies of scale are cost savings that arise from producing a large volume of output. For example, mass production of automobiles along an assembly line leads to a much lower cost per car than does building individual autos in small numbers. SMEs also have fewer options for buffering economic downturns; their limited internal resources often lead to lower credit ratings and less access to external resources, and their small number of employees and smaller operations mean that SMEs are generally less diverse, both in their operations and in their staff. These differences combine to create two important effects. First, SMEs are far more common in service industries than in manufacturing. Second, SMEs suffer from the liability of smallness, which refers to small organizations’ greater chance of failing compared to larger organizations in the same industry or situation.[11]

In addition, entrepreneurs starting small businesses will also suffer from the liability of newness, which refers to new organizations’ greater chance of failing compared to older organizations in the same industry or situation. Older organizations have established reputations and past successes. Their members have had the chance to develop routines and adjust to their work. All of these features may make older organizations more resilient and better able to secure resources from the environment (though existing businesses that create negative social and ecological resources may not be well suited to attracting resources in a market that increasingly values sustainable business). Indeed, research suggests that 20 percent of new businesses fail within the first year of operation, and 50 percent within the first five years of founding.[12] However, innovative SMEs can overcome these limitations through strategic partnerships and community engagement. MAD Travel, for instance, developed partnerships with organizations like the Hineleban Foundation and celebrity advocates to amplify their impact beyond the limits of their size and newness.

SMEs may be more nimble than large corporations, as was evident when the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how innovative SMEs can adapt to severe challenges. When traditional tourism became impossible, MAD Travel was able to launch two new online initiatives, MAD Market and MAD Courses. This adaptability helped sustain community income during the crisis while expanding the organization’s impact beyond traditional tourism.[13]

Despite the challenges they face, SMEs are the core of most national economies. In Canada, 98 percent of all businesses have fewer than 100 employees, and those small organizations employ 8.2 million people, which is more than 70 percent of all private (non-government) jobs in the country.[14] SMEs represent over 97 percent of all firms in countries like Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Japan, New Zealand, Thailand, and the United States.

SMEs not only create jobs, they also tend to create jobs that lead to enhanced social well-being. Surveys suggest that employees in SMEs enjoy higher job satisfaction, better working conditions, more control at work, and have less desire to quit.[15] Small businesses also may offer employees the opportunity to develop and use a wider variety of skills, and to see more clearly how their work relates to the organization’s mission and outcomes.[16] Both of these opportunities tend to make jobs more satisfying and meaningful.[17]

SMEs are also increasingly becoming drivers of sustainable development, with most new entrepreneurs in most countries identifying one of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal as a priority.[18] MAD Travel’s experience shows how SMEs can create multiple value streams that benefit both local communities and the environment. Their model of combining tourism revenue with sustainable agriculture and product development enabled their partner communities to increase their resilience and economic stability.

6.2.2. Entrepreneurship and Family Business

As with SMEs, the idea of a family business is also sometimes confused with entrepreneurship, because it is not unusual for start-ups to be managed by a family. Nonetheless, family business and entrepreneurship are two distinct ideas. This is illustrated by the fact that many family-controlled organizations are long past the start-up phase (e.g., Samsung, Walmart, Nike, and Mars). A family business is an organization controlled by two or more members of a single family, in cooperation or in succession. A family is a group of people—typically connected by marriage or kinship ties—who have a shared history, who feel a sense of collective belonging, and who are committed to helping each other build a shared future. For example, if one spouse manages a restaurant while the other handles its accounting and inventory, that restaurant is a family business, as is a firm where an entrepreneur retires and passes control of the organization to their children. Spouses, siblings, and children are the family members most commonly involved, but some family businesses also include in-laws, cousins, and more distant relations.[19]

A hallmark of family business is the strong interpersonal relationships associated with being family members. When making business decisions, family members will think about their family as well as the organization, and issues in the family may influence how members interact. These facts create distinctive advantages and disadvantages.[20]

Family businesses may enjoy at least three advantages. First, family members are often highly motivated to see the organization succeed. They may be willing to stay with a troubled firm or to make sacrifices for its benefit in order to safeguard the future of their family. Second, being a family firm can help attract customers and partners, as “family owned and operated” advertising is often taken to mean that stakeholders will receive better, kinder treatment from the organization.[21] Third, the higher levels of trust and cooperation in families can simplify management and reduce the financial costs of control. In particular, family firms have lower agency costs than non-family firms.

Agency costs refers to the expenses that owners pay to ensure that managers act in the interests of the firm rather than in their own self-interest. Agency theory uses the term moral hazard to describe the risk that managers might use the firm’s resources to benefit other interests to the detriment of the owners’ financial gain. Moral hazard arises when two conditions are met: (1) managers and owners have misaligned incentives such that managers are rewarded for organizational outcomes that the owners do not favor; and (2) there is information asymmetry between managers and owners such that owners have trouble evaluating the performance and choices of managers, because managers know more about organizational operations and can control what information is shared with owners. Since managers in family-owned businesses are often family members, these firms will generally have lower levels of misaligned incentives and information asymmetry, and thus lower agency costs.[22]

However, family businesses also must confront some disadvantages. If success requires sacrifices (e.g., high debt, long hours), members may believe that the business is being placed ahead of the family, decreasing the quality of relationships within the family. Interpersonal conflict in the family may also influence the business. For example, if a married couple starts an organization and then gets divorced, the business may be torn apart. The two brothers who founded the Dassler Brothers Shoe Company, Adi and Rudy, had a serious conflict with each other and their wives did not get along. So the brothers divided their company: Adi started Adidas, and Rudy started Puma. Their continued fighting with each other distracted them from the threat of a then-new start-up named Nike.[23]

Moreover, how one treats family members may not always fit with how one treats business partners. If a family business includes two children but one of those children is clearly more motivated or more competent, how should rewards be distributed? The issue of rewards and performance reviews is also complicated for non-family employees. It is easy for managers to be biased in favor of their family members, and even when they are not, employees may believe such favoritism exists. And if operations go badly, so that the owner has to choose between firing a child or firing the best salesperson in the firm, either choice can have serious consequences. Nepotism refers to preferential treatment of relatives and friends, especially by giving them jobs for which they are not the most qualified. While nepotism is typically not illegal, it is often seen as unfair and is frequently a poor business choice. Nonetheless, nepotism is not unusual in family businesses, and frequently trumps other decision-making criteria.

6.2.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Entrepreneurship

FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to entrepreneurship have important differences. FBL entrepreneurs are most concerned with financial returns, and so are most likely to be concerned with how new ventures contribute to economic activity and growth. Small businesses may be especially attractive to them because their small budgets can produce relatively high rates of return, especially if they grow quickly. Likewise, with regard to family business, FBL entrepreneurs are likely to value the reduced agency costs, the potential for low labor costs during the early years, and the ability to provide family members with relatively high pay after the firm has become a financial success.

Like FBL entrepreneurs, TBL entrepreneurs seek to create jobs, but in addition they seek to create jobs that are more satisfying and loyalty-inspiring for employees, even when they are paid less than in large firms. The TBL approach is evident in small businesses that target specific ways to profitably reduce negative externalities. For example, Tom Szaky founded TerraCycle after he discovered that he could profitably take waste from the kitchen at the university where he was a student, feed that waste to worms, and sell the worms’ excrement in used soda bottles as plant fertilizer.[24] The TBL view of family business is also similar to that of FBL entrepreneurs, but with more recognition of opportunities to bring family members closer together and to take care of the next generation.[25]

From a SET perspective, perhaps the most important benefit of entrepreneurship is its potential for creating positive socio-ecological innovations. With regard to the advantages of a small business, a SET view shares the FBL and TBL appreciation for low start-up costs and the ability to adopt a narrowly focused strategy, but SET management would also value the greater connection that small businesses often have with their surroundings and the resulting opportunity to build community. If a small business is focused on local stakeholders, it contributes to the local multiplier effect and reduces greenhouse gas–emitting travel. In terms of family business, SET entrepreneurs may often adopt a broader view, focusing on not just their own family, but on humanity or the world as a whole. For example, some SET entrepreneurs have created so-called “universal family firms” that take care of employees and other stakeholders as though they were family members.[26]

Test Your Knowledge

6.3. The Four-Step Entrepreneurial Process

Progressing from the initial inspiration for a new a product or service all the way through to developing and managing an organization that offers that product or service can be a long, complex, and difficult journey that involves experimentation, learning, and stakeholder engagement. As such, it is useful to think of the entrepreneurial process as having four basic steps that often flow back and forth between each other.

6.3.1. Step 1: Identify an Opportunity

The essential first step in entrepreneurship is to identify an opportunity to pursue. Opportunity identification is the process of selecting promising entrepreneurial ideas for further development. Some people mistakenly believe that the biggest challenge of entrepreneurship is coming up with ideas for new products or services, but the greater challenge is actually to identify good ideas, that is, ideas that meet a genuine opportunity or need in the marketplace. If you have ever seen a goofy or unsuccessful product in a discount store or on a shopping channel, or watched Dragons’ Den or Shark Tank, then you know that not all entrepreneurial ideas are equally good.

Sometimes the entrepreneurial opportunity involves purchasing an existing organization. This might be a chance to purchase a franchise for a given location, which allows an entrepreneur to acquire everything that is necessary to open an organization affiliated with a larger brand (e.g., McDonald’s, Lululemon, One World is Enough[27]). At other times, the entrepreneurial opportunity involves purchasing an organization that is already operating rather than starting from nothing. It can be especially rewarding to purchase an existing business that is underperforming and use one’s creativity and energy to make it successful.

However, entrepreneurship usually starts with identifying an opportunity that results in creating an entirely new organization. Having an entrepreneurial mindset, which enables entrepreneurs to look at situations in new ways, is one of the most important factors in identifying such opportunities.[28] For example, where others saw degraded land, Dionisio saw an opportunity to create a revolutionary form of sustainable tourism. Consider a simple experiment. One class of schoolchildren is shown a picture of a person in a wheelchair and asked, “Can this person drive a car?” The students all answer “no” and give many reasons why not. But when another class is shown the same picture and asked, “How can this person drive a car?” the students generate many creative ideas to help a person who uses a wheelchair to drive a car.[29]

Entrepreneurs are more likely to consider how something can be accomplished rather than think of reasons why it can’t be done. This orientation can be applied on a relatively small scale, such as realizing that a specific market has an unmet need (e.g., there is no fusion restaurant in the neighborhood). Or it can be applied on a large scale, requiring the entrepreneur to create the market as well as the organization. When the founders of Manitoba Harvest Hemp Foods had the idea to sell hemp seed as a health food in North America, there was no demand or supply for their product. They had to lobby the government for permission (growing hemp was previously illegal), source the seeds by teaching and encouraging farmers to grow the plants, develop machinery to extract and process hemp seed, conduct research to show its health benefits, and motivate consumers to buy the product. At one point Manitoba Harvest held 66 percent of the North American hemp seed market.[30]

The sources of opportunities can include changing demographic trends (e.g., an aging population), new technologies (e.g., AI), unexpected events (e.g., COVID-19), known gaps in the market (e.g., how to solve problematic addiction to social media, affluenza), and personal experience (e.g., observations while traveling, visiting with friends, pursuing hobbies). One useful way to identify potential entrepreneurial opportunities is to consider the three types of well-being (described in Chapters 3 to 5) with the goal of creating positive externalities while reducing negative externalities. Today it is common for new entrepreneurs to prioritize good environmental or sustainability practices above economic performance.[31] All entrepreneurs have to consider financial well-being outcomes; FBL and TBL organizations seek to maximize them for the organization, while SET organizations need to at least maintain financial viability. But different management approaches pay differing amounts of attention to social and ecological well-being outcomes. As a result, different types of entrepreneurs will focus on different kinds of opportunities.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Identifying an Opportunity

FBL entrepreneurs are constantly looking for more financially rewarding ways to meet needs and wants. They look for places where they can outperform existing competitors, either by lowering financial costs or by providing unique added value. They look for opportunities to invest resources that will yield a higher financial return than they currently earn. FBL entrepreneurial opportunities may focus on reducing a firm’s operating costs, even if it increases negative social or ecological externalities, because such issues do not concern FBL entrepreneurs (they assume that other parties, such as government, are responsible for addressing issues related to externalities). For example, FBL entrepreneurs may increase their financial value capture by outsourcing production to low-paying overseas factories, despite job losses locally and the poor working conditions overseas.

TBL entrepreneurs also seek maximum financial return, but with a focus on opportunities to profitably reduce negative social and ecological externalities. TBL opportunities are increasing, thanks to consumers’ growing support for organizations that are more socially and ecologically responsible. This is evident in many firms that are making pledges to be “net zero” by a certain date, or that make contributions to important causes. Unfortunately, this also increases the temptation for firms to engage in activities designed to increase their reputation for being socially and ecologically responsible firms but which critics suggest amount to greenwashing (see Chapter 3).[32] Examples of greenwashing include McDonald’s introducing paper straws that aren’t recyclable, Coca Cola (perhaps the worst plastic polluter in the world) running ads that feature cute cartoon animals singing about fixing the planet and recycling, and the 60 percent of fast fashion brands making misleading sustainability claims.[33]

SET entrepreneurs look for viable opportunities that help to increase social or ecological well-being. MAD Travel illustrates this approach well—while maintaining financial viability, the organization has created multiple positive externalities. These include environmental benefits through the planting of over 45,000 trees, social benefits through significant income increases for partner communities (ranging from 15 percent to over 100 percent), and cultural benefits through the preservation and celebration of Indigenous knowledge and practices.

Another example is BUILD, a company that creates positive societal externalities by hiring chronically unemployed people like ex-convicts. The company also minimizes negative ecological externalities by installing energy-efficient toilets and insulation for homeowners.[34] The SET approach represents a different way of entrepreneurial “seeing” than the FBL and TBL approaches. Also, SET entrepreneurs emphasize opportunities that meet needs, rather than creating or meeting wants. Sometimes SET entrepreneurs even try to eliminate the need for their product or service. For example, the Digger Foundation, a Swiss organization, supports the design of machinery to remove land mines, with the goal of helping eliminate all land mines so that there will be no need for their equipment.[35]

Test Your Knowledge

6.3.2. Step 2: Test the Idea

The second step in the entrepreneurial process is to determine whether or not the idea is a viable opportunity. This usually involves talking about your idea with potential customers, employees, suppliers, and other stakeholders, as well as developing a prototype. For example, MAD Travel learned by alternating between hosting tours and learning from stakeholders (tourists, Indigenous hosts, and other organizations). By starting small and gathering feedback from many sources, Dionisio was able to refine his business model before scaling up operations.

The most important feedback for an entrepreneur will come from potential users of the good or service (i.e., future customers), but useful information can also be gained from industry experts, government officials, suppliers, competitors, community members, and potential employees. One of the best ways to get this feedback is by using a preliminary elevator pitch, which is a succinct description of the entrepreneur’s plan and the value it offers. A good elevator pitch focuses on the potential opportunity—what need you are satisfying, how the need will be met, and the benefits of doing so. The elevator pitch must be brief and focused on the most important details. It should

- identify the problem you propose to address,

- describe your proposed solution (if appropriate, include a prototype or beta version),

- recognize the major challenge or obstacle,

- have a solution for the challenge,

- explain how your plan benefits the customer,

- be thirty to sixty seconds long, and

- be focused, clear, and delivered in a compelling and enthusiastic fashion.[36]

The most effective pitches and ideas will be persuasive, which means they will change the audience’s thinking or motivate them to take some action (see also Chapter 17 on how entrepreneurs develop compelling stories to communicate with stakeholders). Therefore, the pitch must have a goal. For example, if you are giving your first pitch to a potential customer, then the goal is them excited and asking for more information. Sharing your pitch with stakeholders will allow you to judge others’ reactions and revise your goals accordingly. Talking with customers may help you to identify important product features that you overlooked. Talking to potential employees can identify production issues before they become problems. In MAD Travel’s case, early feedback from the Aeta community led it to expand its model beyond simple tourism to include multiple revenue streams through product development and agroforestry, demonstrating how stakeholder input can fundamentally reshape a business model. Entrepreneurs should use an iterative approach in which they give their pitch, listen to the reaction, revise their pitch, and then try it again with another stakeholder.[37] The goal is not to present a refined end product but rather to determine whether your idea has merit and potential.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Testing the Idea

The FBL approach to idea testing focuses on financial data such as the size of the market, price points, and production costs. The TBL approach includes these concerns but also focuses on identifying a particular negative social or ecological externality that can be profitably addressed. The SET approach focuses on soliciting feedback from the widest array of stakeholders and is most likely to welcome input from stakeholders to co-develop the idea. MAD Travel’s approach illustrates how financial, social, and ecological aspects can all be evident in the testing phase, by including financial metrics (tourism revenue and income streams for Indigenous communities), environmental indicators (trees planted, carbon sequestration), and social impact measures (cross-cultural relationship-building and understanding). By 2023, this comprehensive approach allowed MAD Travel to demonstrate success across multiple dimensions: income increases of up to 103 percent for partner communities, 45,000 trees planted, and a sustainable stream of participating tourists and hosts.

Test Your Knowledge

6.3.3. Step 3: Develop a Plan

Once an entrepreneurial opportunity has been identified and tested, the next step in the entrepreneurial process is to develop a written plan that provides clear direction by laying out objectives and the strategies that will be used to reach those objectives.[38] Research has shown that entrepreneurs with business plans are more than twice as likely to actually launch their new ventures,[39] and that entrepreneurs are more likely to reach their goals if they have a sound plan.[40] First, the plan ensures that entrepreneurs have taken the time to think through the different aspects of the new venture before they begin. Once a new venture is started, the demands of running the organization leave little time for such reflection. Second, preparing a plan forces entrepreneurs to establish goals and standards for subsequently measuring performance. For example, an entrepreneur may decide that a new venture should generate at least $200,000 in revenue in the first year of operation or have a positive cash flow within two years. If such milestones are not met, then the entrepreneur may leave the venture rather than investing any more resources in it. Finally, perhaps the most important reason to write a well-developed plan is to win the support of other stakeholders, whether financers, suppliers, employees, or customers.

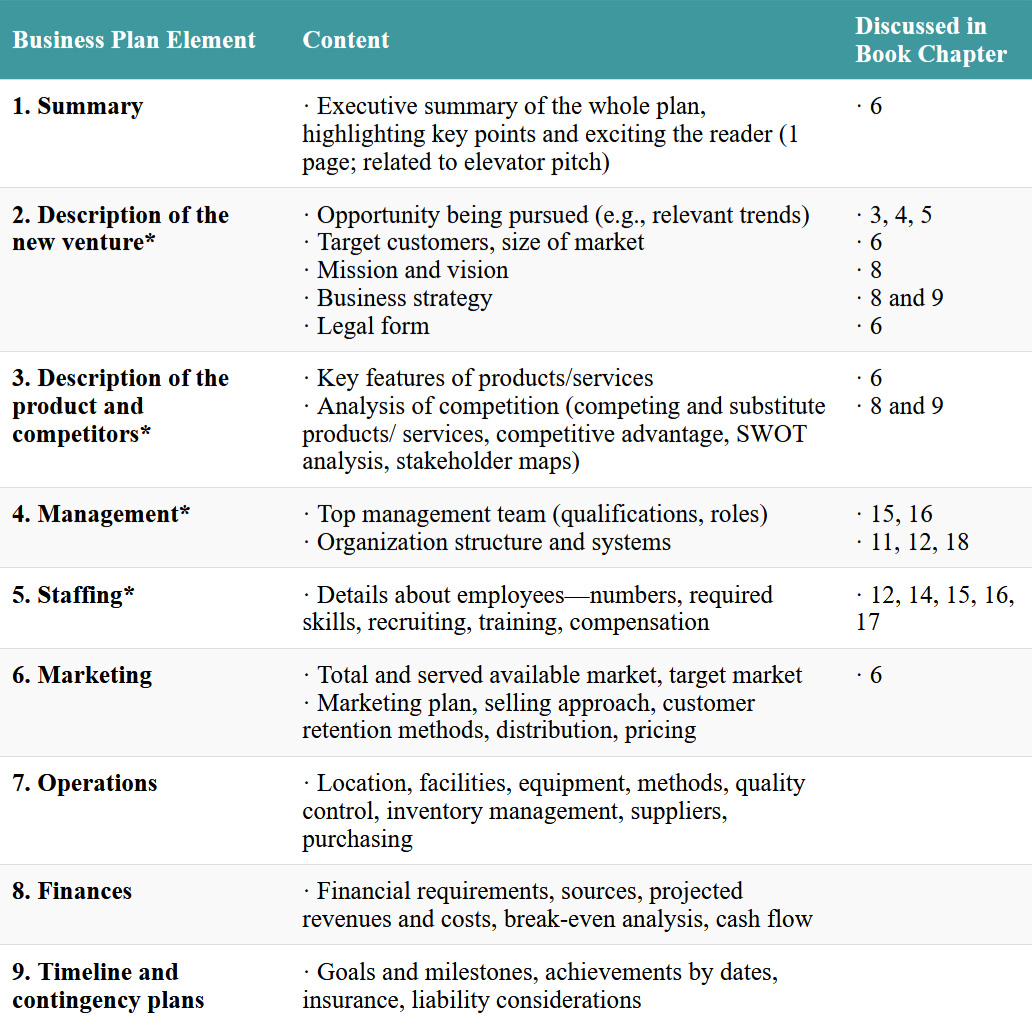

Table 6.1 provides a summary of a generic business plan to describe a potential new organization.[41] A business plan is a written document that describes the key features, actions, structure, and systems for a proposed new organization that is designed to take advantage of an entrepreneurial opportunity. As the term is used here, a business plan can be applied to a wide range of new ventures, not only for-profit businesses. The ESUP, introduced in Chapter 1, is a subset of a business plan. An ESUP includes the elements of a business plan that are relevant for general management (especially those covered in the first five parts in Table 6.1) but does not focus on aspects related to specific functional areas like marketing, finance, and operations. This book provides the necessary information to develop an ESUP, but in order to develop a full business plan you will need to find additional sources of information. For example, if you are a student using this book as a text in a management course, then you may gain the additional material from your other courses (e.g., marketing, operations, accounting, finance, etc.). If you are an entrepreneur, you may find other individuals who can bring expertise in areas outside this book to your management team (e.g., a marketer, an accountant).

Table 6.1. Elements of a generic business plan (including the 5 elements of an ESUP*)

Note that the order and components of the plan in Table 6.1 are merely suggestive; it is best to allow specific characteristics of the new venture to help shape the writing of the business plan. Certain organizations may emphasize some elements more than others (e.g., location is essential for a retail shop but less important for an online consulting firm), and different audiences may be more interested in some elements than others (e.g., potential employees may care most about human resource policies). Nonetheless, Table 6.1 provides a checklist of the elements that should be considered for any business plan. We will briefly describe each element in turn.

1. Summary

The summary is your chance to make a positive first impression. Think of the summary as a written version of your elevator pitch. If your summary is bland or dull, potential investors are unlikely to read the rest of your plan. The summary should provide a brief but engaging description of your new venture, the product or service it will provide, a description of the market it will operate in, the key features that are likely to make it succeed, the resources that are already in place, the additional resources that may be needed, and an appraisal of the venture’s expected performance (financial, social, and ecological). The summary should be short—no longer than one or two pages—and should be written after all the other parts of the plan are complete.

2. Description of the New Venture

This section of the plan introduces readers to the concept of the new venture. It has five components: (i) the opportunity that is being pursued, (ii) the target market, (iii) the mission and vision, (iv) the business strategy, and (v) the legal form of the new organization.

The opportunity: This describes the problem or opportunity that the new venture is addressing, and the relevant trends or gaps in the larger environment that have given rise to the opportunity. This includes the elements of economic, social, and ecological well-being described in Chapters 3–5.

Target market: The business plan should describe the characteristics and size of your target market (and thus the potential size of the new venture). In this context, a market is the group of people or organizations that are or could be interested in using your particular product or service. For example, if you are proposing a new daycare in a specific neighborhood, you would include information on things like the number of children who need but do not have access to daycare, the socio-economic status of parents, the length of waiting lists at other daycares in the neighborhood, and the price parents are willing to pay for daycare. To understand the target market, entrepreneurs can refer to the information they collected in the second step of the entrepreneurial process (testing the idea), as well as gather additional information from potential customers, suppliers, partners, and competitors (see 6. Marketing, below).

Mission and vision: As will be discussed in Chapter 8, this part of your business plan describes the ongoing purpose of the organization, as well as your vision of what the organization will look like in five years.

Business strategy: As will be discussed Chapters 8 and 9, this identifies whether the new venture’s strategy is primarily based on having low financial costs, distinct features, minimal negative externalities and/or enhanced socio-ecological well-being.

Legal form: There are many different legal forms an organization can take, but four basic types are sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation, and co-operative.[42] A sole proprietorship is a business that is owned and operated by one entrepreneur who is responsible for all of its debts. Because sole proprieterships are simple to start, most new ventures take this form. A partnership is established when two or more entrepreneurs own and operate the firm and are responsible for all of its debts. Partnerships are also simple to start and have the advantage of adding more expertise and resources to a firm. Having a written agreement about ownership, dispute resolution, and related issues prior to starting is highly recommended. A corporation is a legal entity separate from its owners that has many of the legal rights of a person and that limits the financial liability of the owners to the amount of their investment in the corporation. Corporations are owned by shareholders, who in turn elect a board of directors who oversee and take legal action for a firm. Corporations are costlier to start and operate due to numerous government regulations, but they offer advantages of limited liability and greater continuity over time. New corporations usually start as private corporations (i.e., where shares cannot generally be bought by the general public). Finally, a co-operative is jointly owned and run by its owners, primarily to provide goods and services for their own benefit. In a co-operative (“co-op”), every owner gets one vote to elect the board (i.e., owners can purchase only one share each), and one usually cannot be part of the organization without owning a share. There are co-ops in all industries and fields, including financial services (e.g., credit unions) and housing (e.g., condominium owners’ associations). Co-operatives can be owned by employees, customers, suppliers, or residents.

3. Description of the Product and Competitors

This section of the business plan describes the products and services the new venture will offer (including key features and price points), how they compare with competitors, and how they fit into the larger market. Competitors are other organizations that offer similar products or services, or that offer products or services that meet the same customer need. Preparing this step can involve drawing stakeholder maps, describing similar products and services being offered in the marketplace, and providing an analysis of the new venture’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (see Chapters 8 and 9).

4. Management

This section describes the top management team, the basic management philosophy or approach, and the organizational structure and systems of the new venture. It should convince readers that the necessary management capability to make the venture successful has been assembled. Potential funders of a new venture place great emphasis on the characteristics of the entrepreneurs leading a new start-up, and particularly their ability to work as a cohesive team.[43]

When writing a start-up plan, be sure to provide a clear description of the management team’s experience and expertise. Specify which member will do what work (e.g., who will manage areas like finance, accounting, human resources). Identify any gaps and plans to use advisers and consultants to fill those gaps. Provide information about how much time and energy key people will invest in this venture, and how they will be compensated. For example, which members are willing to put in sixty hours a week, and which have other jobs and commitments that will limit their participation?

Information on the organization’s basic management philosophy should reflect whether the venture will adopt an FBL, TBL, or SET management approach, and include information about how the management approach and strategy fits with the organization’s structure and systems (Chapters 10 and 11).

5. Staffing

In addition to describing the top management team and organizational structure and systems, the plan should provide additional details about the number of employees needed, the sorts of skills and credentials required inside the organization (and what skills will be outsourced), how employees will be recruited, trained, and compensated, approaches to motivation that will be used, and information about leadership approach and use of groups and teams, and so on (Chapters 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17).

6. Marketing

The marketing section of a business plan provides detailed information about three key components of the market: TAM, SAM, and your target market.[44] The total available market (TAM) includes everyone who could potentially benefit from the product or service. The served available market (SAM) includes everyone in the TAM who is likely to actually use the product or service. The target market includes everyone in the SAM that the organization will intentionally try to make into a customer or client in the near future. For example, if you were planning a new daycare, the TAM might include every household within a one-hour driving distance that has children living there. The SAM would include those households in the TAM that need but do not currently have daycare services. The target market would be the members of the TAM that your specific organization is going to prioritize as customers (full-time vs. part-time care, children of particular ages, etc.).

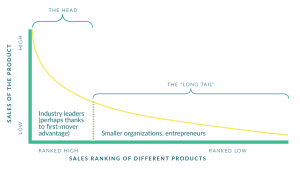

This section also includes your marketing plan, selling approach, customer retention methods, distribution, pricing strategy, and so on. An important consideration is whether the new venture’s products and services may be able to attain a first-mover advantage, which is a performance advantage enjoyed by the first organization or product to reach a large portion of the potential market. For example, the QWERTY keyboard is dominant not because it is better than other keyboards but because it was the first to be mass-produced (see Chapter 2). Growth-oriented entrepreneurs will be most concerned with first-mover advantage, because their goal is to create the largest possible organization. In contrast, micropreneurs are less concerned with increasing the size of their business and thus are more likely to focus on what has become known as the “long tail.”[45] Many markets are dominated by one or a few large organizations or products, but technology has allowed smaller ventures to reach enough customers to be viable (see Figure 6.1). The few large organizations that control the vast majority of the market are the “head” of the market, but there can still be a large number of organizations in the “tail” that each have a very small portion of the market. For example, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter is the world’s best-selling book series, with more than 500 million copies sold.[46] However, publishers consider a fiction author successful if a book sells “merely” ten to fifteen thousand copies.[47] Because current technology allows an entrepreneur to potentially reach customers all over the world, there are opportunities for many organizations in the long tail of the market, not just as large first movers in the head.

Figure 6.1. The “head” and “long tail” of the market

7. Operations

This section provides detailed information about the new venture’s proposed location, facilities, equipment, methods of transforming inputs into outputs, quality control, inventory management, suppliers, purchasing strategies, and so on. For example, if you are starting a daycare, you need to identify potential sites for the daycare, the available parking facilities, convenience for parents who are picking up and dropping off their children, property taxes, zoning regulations, required liability insurance coverage, whether the site is located close to parks and libraries, the curriculum you will follow, and the supplies and equipment you will need (e.g., crayons, paper, floor mats, outdoor/indoor climbing structures).

8. Finances

A business plan should describe the anticipated sources of financing, financial projections for the first five years, an analysis of expected expenses and revenues, a break-even analysis, and cash-flow statements. The projections should be relatively detailed at first (e.g., quarterly cash-flow projections in the first year) and then become more general over time. An important part of the financial planning for the organization is to identify its sources of financing and specify when these funds are needed. Unless entrepreneurs are self-financed, they usually need either debt or equity financing. Debt financing occurs when entrepreneurs borrow money from a bank, family and friends, or a financial institution that must be paid back at some future date. Collateral such as personal assets or business assets is often required to guarantee a loan. Equity financing occurs when investors in a new venture receive shares and become part owners of the organization. Equity financing usually comes from venture capitalists, which are companies or individuals that invest money in an organization in exchange for a share of the ownership and profits. Venture capitalists often become quite involved in the operations of the business, sometimes even requiring that they approve major decisions.

9. Timeline and Contingency Plans

This section of the plan describes how resources will be mobilized over time, presents expected performance milestones, and identifies contingency plans that will be put in place in case events do not unfold as planned. In terms of the timeline, the business plan should present a timetable or chart to indicate when each phase of the venture is to be completed. For example, the timeline for a new daycare organization should indicate when a location will be selected, when equipment will be installed, when and what kind of advertising will be done, when different staff members will be recruited and hired, and so on. The timeline should also identify specific milestones designed to help the entrepreneurs and investors know how well they are doing. For instance, if a new daycare needs thirty children to be viable and it has only twenty children after two years of operation, then it may be prudent to close the daycare. The timeline should extend at least five years into the future.

Finally, the plan for the new venture should describe how critical risks will be managed if circumstances change. Competitors might engage in price-cutting, or there could be unexpected delays or cost overruns in product development, or difficulties might arise in acquiring timely inputs from suppliers. A new daycare may unexpectedly find a competitor starting up nearby three months later, or its staff may be accused of inappropriate behavior. Contingency planning helps managers to think beforehand how to handle these situations (see Chapter 9). The plan should also describe insurance mechanisms to deal with liability considerations. For example, the plan for a daycare would describe how it would deal with a parent who sues over an injury to their child.

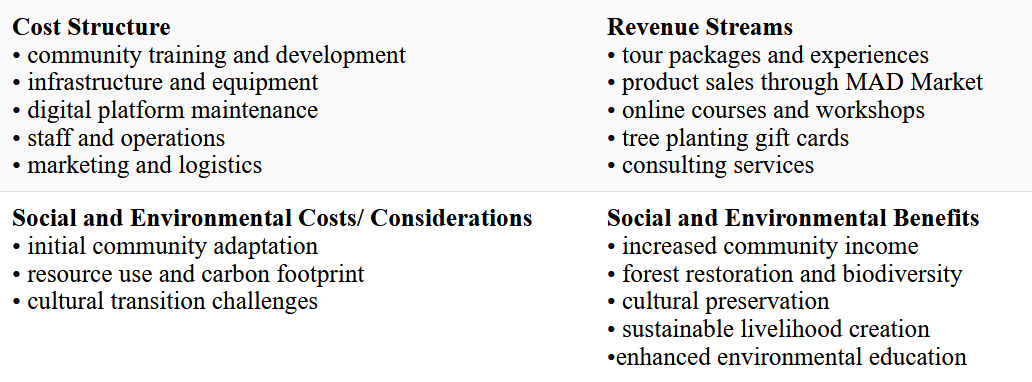

The Business Model Canvas: A More Dynamic Variation of the Traditional Business Plan

While it is essential for entrepreneurs to consider all of the issues described above, it has become less common to describe them all in an exhaustive, written business plan.[48] For example, a study of Inc. 500 firms (the 500 fastest-growing private organizations in the United States) found that only 28 percent had completed a prototypical business plan at the start-up stage, and some research has found no relationship between having a detailed new venture plan and future profitability.[49] Research suggests that a detailed business plan tends to produce good outcomes for new initiatives within an established business (i.e., for intrapreneurship), but that new organizations pursuing classic entrepreneurial ends may be better served by a more flexible, open-ended, and partner-oriented approach to business planning.[50]

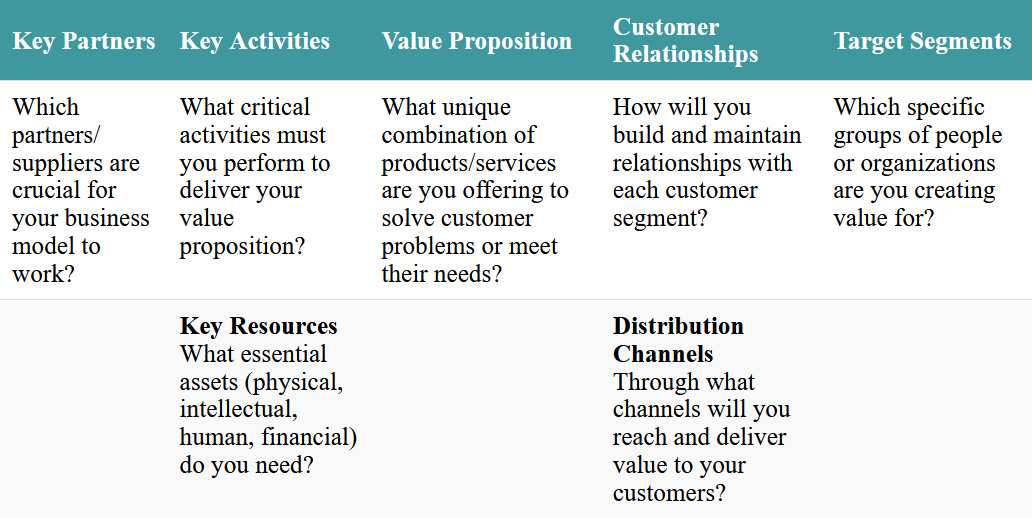

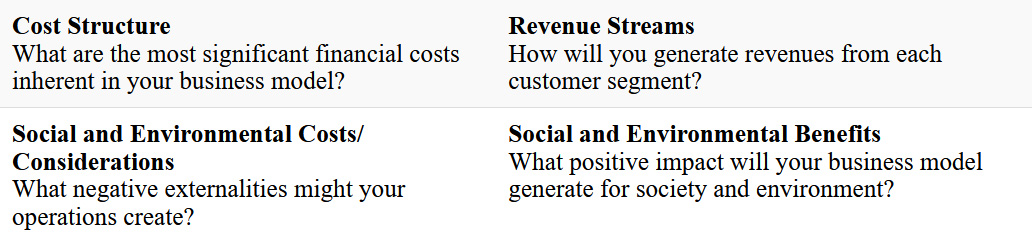

This more flexible approach, where plans become sort of a living document that changes over time, and where the relationships between key components of a business model can be seen at a glance, is evident in the Business Model Canvas framework. A business model describes the inputs and processes an organization uses to create, deliver, and capture value.[51] The Business Model Canvas, depicted in Table 6.2, provides a concise one-page format for entrepreneurs to map out the key components of their proposed venture, such as the value proposition (discussed more fully in Chapter 9), customer segments, revenue streams, and cost structure.[52]

Table 6.2: Overview of key components and content in Business Model Canvas

Whereas a traditional business plan offers more detailed analyses, the Business Model Canvas has its own advantages. First, by enabling entrepreneurs to view their firm from a holistic vantage point, it helps them to better understand how the different components fit together, and thereby to zero in on the key content associated with each component. Second, as content in one component changes (e.g., a change in the type of customers being catered to, a new partner organization, a change in distribution channels), the implications for other components may come to the foreground more easily and be identified more immediately. Third, a Business Model Canvas lends itself to functioning a living document, where changes and tweaks can be made in real time as an organization learns from its experiences. Rather than being a static document, a Business Model Canvas captures a planning-as-you-go dynamic that gets updated with each iteration. For example, detailed financial projections spanning years, which are common in traditional business plans, are replaced by actionable metrics and repeatable growth models focused on near-term validation.

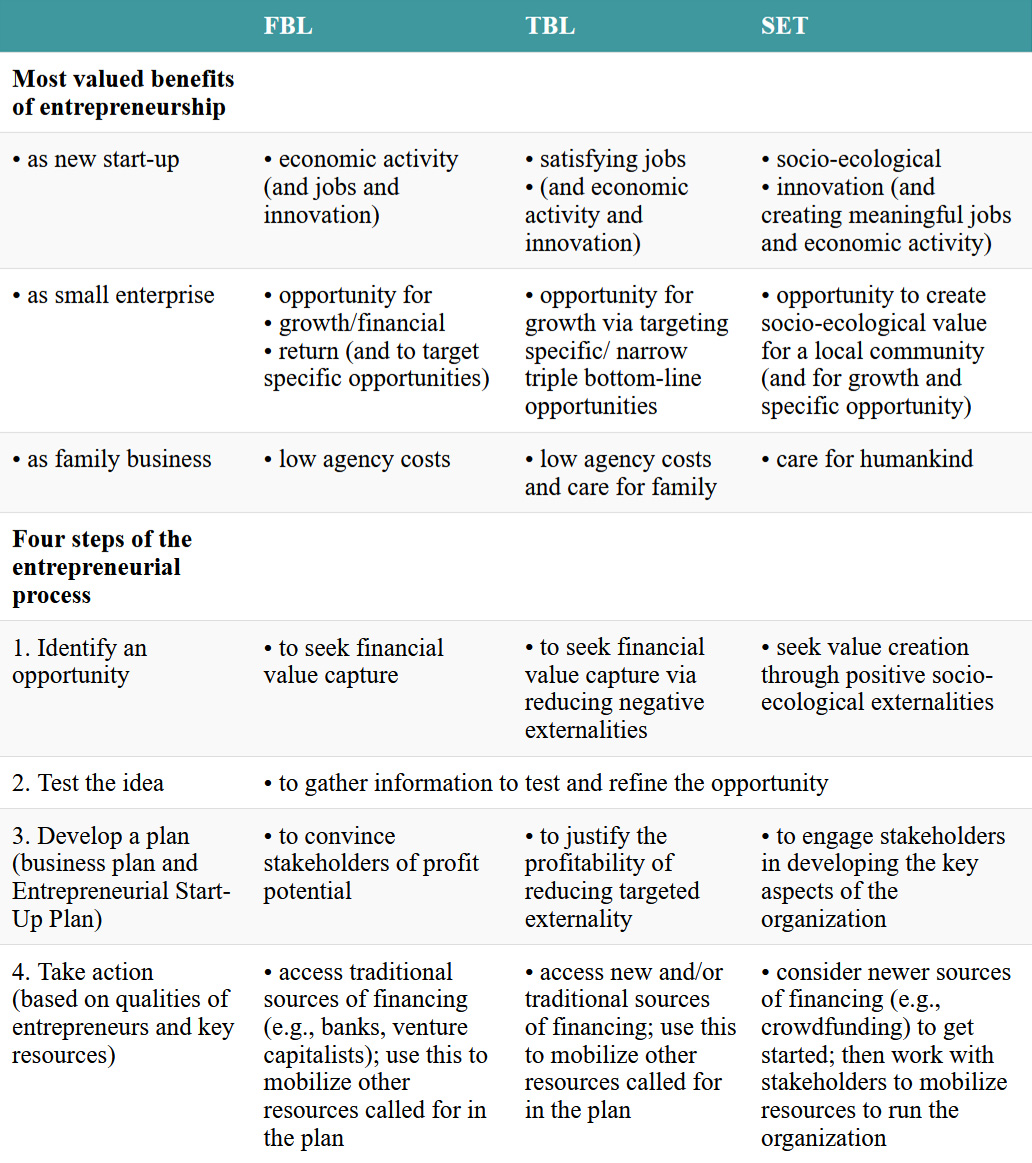

Table 6.3 illustrates the Business Model Canvas for MAD Travel, whose components have changed over time as the company has tested ideas and incorporated feedback in the entrepreneurial process. MAD Travel’s initial value proposition focused primarily on sustainable tourism, offering immersive restoration tours that combined environmental conservation with cultural experiences. However, through constant testing and learning from experience and stakeholders, particularly within the Aeta community, MAD Travel discovered additional opportunities to create and capture value. As shown on in Table 6.3, over time MAD Travel expanded its value propositions to include the following:

- for communities—economic empowerment through multiple revenue streams, skills development, and economic restoration

- for customers—authentic cultural experiences, direct participation in ecological regeneration, and access to sustainable products and educational opportunities.

Table 6.3. An example of the Business Model Canvas for MAD Travel

To illustrate the dynamic interrelationships among components that the canvas highlights, consider that when COVID-19 disrupted the distribution channels in its core tourism business (because in-person travel was no longer possible), MAD Travel demonstrated the advantages of having a flexible business model by rapidly introducing two new initiatives:

- MAD Market—an online platform connecting urban consumers with Indigenous producers, creating a new revenue stream while maintaining community support during the pandemic.

- MAD Courses—digital education programs on social enterprise and sustainability, expanding the organization’s impact beyond physical tourism.

The canvas also shows how MAD Travel built a network of key partnerships that enabled this evolution, from Indigenous communities and government agencies to corporate partners and celebrity advocates. Its revenue model similarly evolved from purely tourism-based income to include

- tour packages and experiences,

- product sales through MAD Market, and

- online courses and workshops.

This diversification demonstrates how using a Business Model Canvas can help entrepreneurs identify and test new revenue opportunities while maintaining alignment with (and growing) their core mission. In MAD Travel’s case, each new revenue stream reinforces its commitment to creating positive social and environmental impact.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Developing a Plan

There are important differences in the emphasis FBL, TBL, and SET entrepreneurs place on developing plans for a new venture, as well as in the content of such plans. Highly detailed plans of the sort summarized in Table 6.1 have become less important in modern entrepreneurship,[53] though they continue to be important for some FBL entrepreneurs because they can be used to demonstrate a strong business case for investing.[54] Because the FBL approach prioritizes financial gains, developing a strong business case is crucial for gaining support, and FBL entrepreneurs put considerable effort into providing detailed information about potential customers and comparable firms’ operating costs and similar data. This helps them to make concrete predictions about how much money could be made with the proposed new product or service.[55]

The TBL approach is very much like the FBL approach, but in some ways is even more demanding. Even though the TBL approach is becoming the new norm in the marketplace and there has been a growth in ESG (economic, social, and governance) investing (see Chapter 3), TBL start-ups may face skepticism from traditional banks and investors, because sustainable development has traditionally been seen as a threat to maximizing financial gains. Thus, a TBL entrepreneur must take extra care to reassure potential investors that resources devoted to reducing negative externalities will in fact enhance the organization’s financial performance.

In contrast to traditional FBL and TBL plans, which are ultimately judged on whether or not they optimize the financial return, a SET organization will be judged on its ability to produce positive social or ecological outcomes in a financially sustainable fashion. Because the SET approach emphasizes multiple forms of well-being for multiple stakeholders through active cooperation with those stakeholders, a SET entrepreneur may be less able to anticipate and define everything in advance. As a result, SET entrepreneurs have often devoted less time to crafting detailed and specific plans. One might say that whereas FBL and TBL entrepreneurs rely on a business plan to convince stakeholders to support them, SET entrepreneurs use stakeholders to develop a convincing plan.

Test Your Knowledge

6.3.4. Step 4: Take Action

The final step in the entrepreneurial process may be the most difficult. It is one thing to write an excellent plan; it is another thing to implement the plan and launch a new organization. One study found that even among plans that had won at business plan competitions, only 30 percent of those were put into action.[56] There may be a variety of reasons for this. Perhaps the prize-winners pursued an even better idea for a new start-up. Perhaps they did not have the entrepreneurial qualities called for to put their plans into action. Or, perhaps they were unable to find the necessary financial resources to launch their new organization (venture capitalists fund only 2 percent of the plans they see, and large banks approve about 25 percent of start-up business loan requests).[57] In any case, writing a great business plan and implementing it are two different things. In the remainder of this section, we briefly describe entrepreneurial qualities that make a person more likely to take successful action, as well as differences among FBL, TBL, and SET approaches approaches to the financial issues related to launching a new venture.

Qualities of Entrepreneurs

Studies suggest that a variety of qualities distinguish entrepreneurs who launch successful start-ups,[58] including personality characteristics like being conscientious, open to new experiences, extraverted, and emotionally stable.[59] A strong desire for achievement also contributes to entrepreneurial success, as does having a high level of self-efficacy, which is the confidence and belief that one can accomplish a task successfully.[60] Enjoying risk makes individuals more likely to start their own organizations, but it does not help them to succeed.[61]

Other important qualities include managerial social skills such as leadership (see Chapter 15), being able to build and maintain a cohesive team (Chapter 16), and the ability to communicate with others (Chapter 17).[62] New venture success increases with the size of the founding management team.[63] Entrepreneurs working alone are far less likely to succeed, because a lone entrepreneur has fewer skills, fewer contacts, and less experience than a team.[64] Most investors consider the management team and their combined qualifications to be an essential criterion for providing financial support.[65] Education is also positively associated with entrepreneurial success,[66] and a lack of education is a primary barrier to acquiring start-up financing.[67] However, industry experience is a more important predictor of success.[68]

An important consideration is the entrepreneur’s gender. Even in developed market economies, where we might expect to find fewer social barriers suppressing female entrepreneurship, only 25 percent of businesses are owned and managed by women,[69] though that gap may be decreasing (in 2023, about 45 percent of new businesses globally were started by women[70]). Several reasons may help to explain why women have been less likely to become entrepreneurs. First, women tend to report lower self-efficacy than men[71]—even when they really have equal skill and knowledge[72]—and thus fewer women may choose an entrepreneurial career.[73] Second, investors seem biased in favor of male entrepreneurs.[74] Third, female entrepreneurs tend to choose different industries and locations for their organizations, and those choices are often in lower-profile and more challenging contexts.[75] Nonetheless, women have just as much entrepreneurial potential as men: studies show that when the barriers just mentioned are removed, women are as likely as men to be successful entrepreneurs.[76]

In addition to personal attributes, the life situations of individuals can also influence whether they become entrepreneurs. People are more likely to start a new organization after experiencing a transition in their lives. This includes completing an education or training program, finishing a major project, moving, having a midlife crisis, and being divorced or fired. For example, Boldr was started after the death of the founder’s best friend (Chapter 5). And after their start-up was purchased by eBay, the founders of PayPal went on to start other companies, including Tesla, LinkedIn, YouTube, Yelp, and Yammer. People are also more likely to start a new organization if their current job is dissatisfying, or if they have little hope of finding satisfying employment. These necessity-driven entrepreneurs often feel pushed into action. For example, Tom Chappell left his corporate job to “move back to the land” and founded Tom’s of Maine (a SET company that sells sustainable personal care products like toothpaste and hand cream). Finally, people may become entrepreneurs to pursue a specific opportunity or because their situation otherwise pulls them toward a new venture. Available resources, mentors, or supports can help a person take the leap into entrepreneurship.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Taking Action

As described throughout this book, an entrepreneur’s management approach will have a significant effect on how a new venture is started and managed. Here, we will briefly highlight some differences related to the legal form and financing a start-up might pursue. FBL and TBL entrepreneurs, with their focus on high returns for invested capital, are well positioned to appeal to traditional financial institutions and similarly motivated investors. It often makes sense for such entrepreneurs to start a corporation, with its advantages, because managers of corporations are (in many jurisdictions) legally required to pursue profits for shareholders.[77]

In contrast, SET entrepreneurs do not prioritize the maximization of financial gains and therefore may encounter poor responses and difficulties if they seek financing from sources managed based on an FBL approach. The experience of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream illustrates issues that SET entrepreneurs may face when their firm has a fiduciary duty to benefit the owners’ financial interests. Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Holdings Inc. was founded with a SET mission: to make the world’s best ice cream, run a financially successful company, and make the world a better place. The company used local organic inputs, developed chemical-free containers, prioritized fair trade ingredients, and its profits funded a foundation supporting community-oriented projects. But it was also a public corporation, and thus when the European conglomerate Unilever offered to buy the company at a 25 percent profit, the managers of Ben & Jerry’s were legally obliged to accept the offer on behalf of shareholders, even though they feared that the firm’s SET mission would be abandoned by Unilever.[78]

Lawmakers have made changes that reduce the potential conflict between SET organizations and traditional corporate law. They created a new kind of corporation, called a benefit corporation, which is a for-profit corporate entity that has legally defined and recognized social or environmental goals (recall that Greyston Bakery is a benefit corporation, Chapter 1; as is Assiniboine Credit Union, Chapter 3). Whereas shareholders in a traditional corporation may use the law to force managers to pursue profit at the expense of social or ecological outcomes, the shareholders in a benefit corporation may use the law to force managers to pursue social or ecological benefits at the expense of maximizing financial profit.[79]

Even with this change, SET entrepreneurs may have trouble financing their organizations, since most debt and equity financing is controlled by FBL-oriented organizations.[80] However, research suggests that up to one-third of retail investors already willingly compromise their need to maximize financial returns in order optimize social and ecological well-being.[81] SET entrepreneurs often do better if they can connect directly with such like-minded investors, and so have contributed to the rise of new financing options. The most important of these is crowdfunding, which involves entrepreneurs receiving small amounts of money from a large number of people, often in exchange for a reward (but typically not repayment of the funds or a role in management).[82] In this model, the entrepreneur describes their project and goals—often via a short elevator pitch video—and requests funds from interested and supportive individuals. The specifics of crowdfunding vary. For example, Kickstarter, the largest and best-known organization providing a crowdfunding service, requires the proposed project to have defined start and end dates, to offer rewards to funders, and in the case of physical products, to share information about a prototype. In contrast, Indiegogo has less strict guidelines (e.g., not requiring rewards for funders). Some crowdfunding campaigns set specific goals, and if that goal is not reached, the donors receive their money back and the entrepreneur gets nothing; other campaigns allow the entrepreneur access to whatever funds are offered.

Crowdfunding on a large scale is a relatively new phenomenon and, thanks to communication technology, continues to develop. For example, in 2016, Indiegogo began a trial of a new equity crowdfunding service that allows individuals to receive partial ownership in return for their funds (i.e., they become true investors rather than just donors). Whatever form it takes in the future, crowdfunding has become an important part of entrepreneurial financing. It has been growing at a remarkable pace, from an $880 million activity in 2010 to an estimated $300 billion in 2025.[83]

The remainder of the book will provide much more detailed information of this fourth phase, “Take action” regarding the management of entrepreneurial start-up organizations, and consider differences between FBL, TBL, and SET entrepreneurs. This will culminate in Chapter 18, which describes the control and information systems called for in managing an organization, and also introduces more discussion of the different business functions (e.g., finance, marketing, operations, and accounting).

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Entrepreneurship creates the vast majority of radical innovations and new jobs in an economy, and the jobs created by entrepreneurs often foster higher levels of social well-being than those in existing large organizations.

- Many entrepreneurial ventures are small or family businesses, but not all small or family business are entrepreneurial.

- The entrepreneurial process is iterative, involving experimentation and stakeholder engagement. The four steps in the entrepreneurial process are

- (i) identifying an opportunity (a promising idea that meets a need);

- (ii) testing the idea (developing a prototype, using an elevator pitch to gather feedback);

- (iii) developing a plan (e.g., a business plan, an Entrepreneurial Start-Up Plan, a Business Model Canvas); and

- (iv) taking action (mobilizing resources to put your evolving plan into practice).

- A generic business plan consists of the following nine elements: summary; description of the new venture; description of products and competitors; management; staffing; marketing; operations; finances; and timeline and contingency plans.

- Entrepreneurial planning is shifting from traditional detailed business plans to more dynamic frameworks like the Business Model Canvas that facilitate and highlight the important work of ongoing testing and learning from experience and stakeholders.

- Differences in management approaches lead entrepreneurs to formulate different goals and value propositions but can also lead to different organizational forms, sources of financing, and relationships with stakeholders.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- What are the key benefits of entrepreneurship for society?

- Identify and describe the four steps of the entrepreneurial process. What are key differences between the FBL, TBL, and SET approaches in each of the four steps?

- Identify and describe the elements of a business plan for a new venture. How are these elements related to the entrepreneurial process?

- Describe three key differences between writing a business plan and using a Business Model Canvas for entrepreneurs. Identify at least two relative advantages for each. Which would you be more likely to use, and why?

- How often do you talk with your friends or family about ideas for starting a new venture? What qualities do you share with entrepreneurs who succeed at putting good ideas into practice? How are you different? What resources would you need to put your ideas into practice? Explain your answer.

- If you were to start a new venture, what opportunity would you like to pursue? How would you assess its potential for creating economic, social, and environmental value? What trends, surprises, or gaps have you noticed? What possibilities do they suggest?

- If you became an entrepreneur, would you adopt an FBL, TBL, or SET approach? Why? What implications does that choice have for how you would develop your organization?

- Use the information in this chapter regarding the parts of an Entrepreneurial Start-Up Plan (ESUP) to create the framework for a new venture you might pursue. Begin to complete the sections as you are able, especially drawing on your responses to ESUP-related questions presented in previous chapters. Continue to fill in your ESUP as you work your way through the rest of this book.

- Use the information in this chapter regarding the Business Model Canvas to describe a new venture you might pursue. Begin to fill in the sections as you are able.

- Aure, P. (2024, August 22). [Good Business] Sparking the Filipino diwa towards nation-building. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/business/good-business-opinion-sparking-filipino-diwa-towards-nation-building/; Dionisio, R. I. (2024, September 5). [Good Business] Beyond extraction: Sustainable business models rooted in Filipino soil. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/business/opinion-beyond-extraction-sustainable-business-models-rooted-filipino-soil/; Young entrepreneurs recognized in 2024 RVR Siklab Awards. (2004, September 9). BusinessWorld. https://www.bworldonline.com/sparkup/2024/09/09/619904/young-entrepreneurs-recognized-in-2024-rvr-siklab-awards/; The story of MAD (Making a Difference) Market with Raf Dionisio. (2020, May 18). Our Awesome Planet. https://www.youtube.com/live/NxLkgrJPEVI?si=pToZXSzbk8WtnI-P ↵

- Dionisio, R. (2020, November 2). Tourism promotions board COVID19 meaningful pivots Rafael Dionisio MAD: Travel Market Courses. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q65F_GpglEM. Emphasis added here. ↵

- Aguinaldo, M. A. L. (2020, May 11). How MAD Travel is tackling tourism in the time of COVID-19. BusinessWorld. https://www.bworldonline.com/community/2020/05/11/293704/sparkup-community-how-mad-travel-is-tackling-tourism-in-the-time-of-covid-19/ ↵

- Intrapreneurs—the entrepreneurs who work within existing organizations—are discussed in other parts of the book, most notably in Chapters 1 and 13. ↵

- Kane, T. J. (2010). The importance of startups in job creation and job destruction. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1646934, or https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1646934 ↵

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2017). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2017. https://doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2017-en ↵

- Hunt, R., & Ortiz-Hunt, L. (2017). Entrepreneurial round-tripping: The benefits of newness and smallness in multi-directional value creation. Management Decision, 55(3): 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2016-0475 ↵

- See page 175 in Daft, R. L. (2003). Management (6th ed.). Thomson South-Western; Hellriegel, D., Jackson, S. E., & Slocum, J. W. (2002). Management: A competency-based approach (9th ed.). Thomson South-Western. ↵

- Deloitte (2014, January). The millennial survey 2014: Big demands and high expectations. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-dttl-2014-millennial-survey-report.pdf; Zetlin, M. (2013, December 17). Survey: 63% of 20-somethings want to start a business. Inc. https://www.inc.com/minda-zetlin/63-percent-of-20-somethings-want-to-own-a-business.html ↵

- Page 19 in Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). (2024). GEM 2023/2024 Global Report: 25 years and growing. https://gemconsortium.org/report/global-entrepreneurship-monitor-gem-20232024-global-report-25-years-and-growing ↵

- Freeman, J., Carroll, G. R., & Hannan, M. T. (1983). The liability of newness: Age dependence in organizational death rates. American Sociological Review, 48: 692–710. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094928 ↵

- Based on US data, 1993–2013; cited in Solis, C. J. (2016). Small retail business owner strategies needed to succeed beyond 5 years [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies 2583. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/2583 ↵

- Aguinaldo (2020). ↵

- OECD (2017). ↵

- García-Serrano, C. (2008). Does size matter? The influence of firm size on working conditions and job satisfaction( ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2008-30). Institute for Social and Economic Research. https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/files/working-papers/iser/2008-30.pdf ↵

- See page 136 in Hellriegel et al. (2002); see also page 236 in Schermerhorn, J. R. (2002). Management (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Fried, Y., & Ferris, G. R. (1987). The validity of the Job Characteristics Model: A review and meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 40(2): 287–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00605.x ↵

- GEM (2024). ↵

- Longenecker, J., Petty, J., Palich, L., & Hoy, F. (2013). Small business management (17th ed.). South-Western College Publishers. ↵

- Sirmon, D. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 27(4): 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00013 ↵

- Micelotta, E. R., & Raynard, M. (2011). Concealing or revealing the family? Corporate brand identity strategies in family firms. Family Business Review, 24(3): 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511407321; Funk, J., & Litz, R. (2009, April). Got family? The influence of “family” identity on customer loyalty [Poster presentation]. Family Enterprise Research Conference, Winnipeg, Manitoba. ↵

- Dodd, S. D., & Dyck, B. (2015). Agency, stewardship, and the universal-family firm: A qualitative historical analysis. Family Business Review, 28(4): 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515600860 ↵

- Alderson, K. (2015). Conflict management and resolution in family-owned businesses: A practitioner focused review. Journal of Family Business Management, 5(2): 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-08-2015-0030 ↵

- Szaky, T. (2013). Revolution in a bottle: How TerraCycle is redefining green business: Penguin. ↵

- Funk, J. (2014). Do family businesses “pay it forward”? Seeking to understand the relationship between intergenerational behaviour and environmentally sustainable business practices [Doctoral dissertation]. Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba. ↵