Part 1: Background and Basics

2. A Short History of Management Theory and Practice

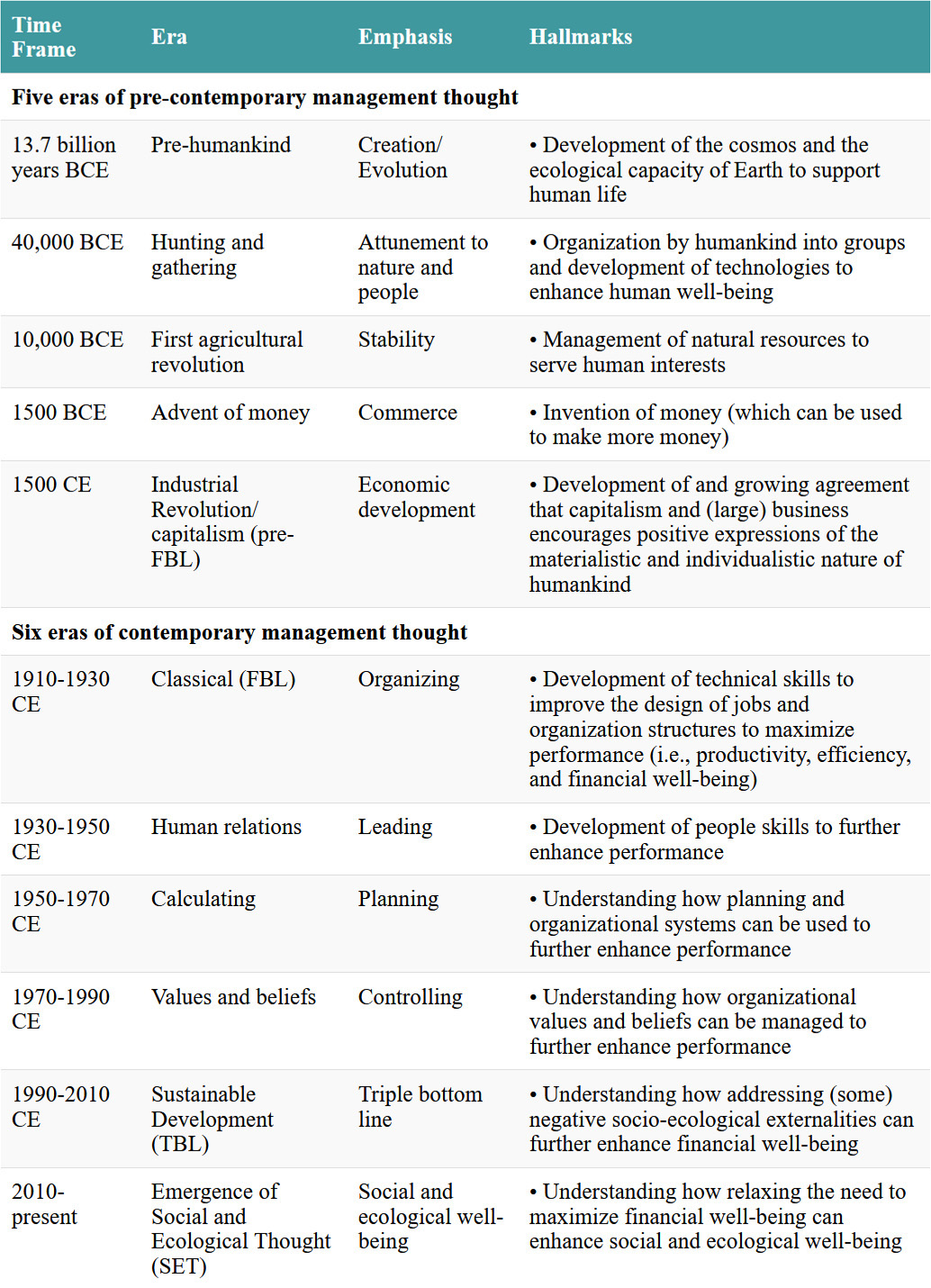

Chapter 2 provides a historical overview of pre-contemporary and contemporary management thought, as summarized in the following table and whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe five key historical eras that predate and provide the context for the development of contemporary management thought.

- Describe the six eras of contemporary management thought.

- Describe how differences among FBL, TBL, and SET approaches are informed by and aligned with the different eras.

- Understand what it means to say that management is socially constructed, and think about how you will participate in socially (re)constructing the meaning of management in your career.

2.0. Opening Case: A Short History of Chocolate

Chocolate may be most people’s favorite flavor,[1] but most of us know little about how the chocolate industry has developed over time, nor about how current chocolate companies are managed.[2] Consider how the meaning of chocolate has been socially (re)constructed throughout history.[3]

Chocolate as idol: The history of chocolate dates back to 1900 BCE among people living in Mesoamerica, where the Mayans worshipped the cocoa bean as an idol closely linked to the merchant god Ek Chuah, and the Aztecs believed cocoa was a gift from Quetzalcoatl, the god of wisdom.[4] In 1753 the Swedish botanist Carl von Linne gave it the scientific name theobroma, where theo means god and broma means food.

Chocolate as money: Both the Mayans and the Aztecs used cocoa beans as currency. In fact, in some parts of Central America the cocoa bean was still being used as currency as recently as the 1800s: with ten cocoa beans you could buy a rabbit, and with 100 you could buy a slave. When the Spanish explorer Don Hernán Cortés was introduced to a chocolate drink by the Aztec emperor Montezuma, Cortés may not have liked the taste but he did like the idea that money could grow on (cocoa) trees. Realizing its value as currency, he established a cocoa plantation in order to cultivate cash (this gives new meaning to the idea of a chocolate mint).[5]

Chocolate as medicine: The Mayans used cocoa for treating coughs, fever, and discomfort during pregnancy. The Aztecs thought that wisdom and power came from eating the fruit of the cocoa tree. In Europe some of the earliest cocoa makers were apothecaries (early chemists), interested in the supposed medicinal properties of cocoa. In seventeenth-century Holland, cocoa was recommended by doctors as a cure for almost every ailment. Today, research points to health benefits from eating dark chocolate, such as reducing the risk of cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

Chocolate as an agent of social well-being: Technological breakthroughs by entrepreneurs like C. van Houten—a Dutch chocolate master who invented the cocoa press in 1828 —helped to make chocolate affordable for many more people. At that time many leading businesspeople in the chocolate industry were Quakers, whose motivation included a desire to persuade poor people to give up alcohol in favor of the healthier chocolate drink.[6] One such Quaker was John Cadbury, who started Cadbury Limited in 1831. An important turning point for the company occurred in 1866, when it introduced a process for pressing cocoa butter from the cocoa bean, and by 1879 the firm had become so financially successful that John’s son George Cadbury could afford to build the “factory in a garden” on a park-like property in Bournville, England.[7] Cadbury’s Bournville factory became famous for setting an example of promoting social well-being in the workplace. Cadbury was the first firm to reduce the workweek to five-and-a-half days, encourage workers to continue their education while employed, offer medical and dental departments, and provide workers with a kitchen where they could heat up their dinners. Wanting to offer wage earners affordable housing in pleasant surroundings, in 1895 George Cadbury purchased another 120 acres near the Bournville plant to establish what has become the Bournville Estate, a charitable trust that today covers 1,000 acres and has 7,600 homes.[8]

Chocolate as big business (FBL and TBL management): Once technology enabled chocolate to become a mass consumption item, it soon became big business, with global retail sales topping a sweet $133 billion in 2024.[9] About 60 percent of all chocolate is consumed in the United States and European Union. As the industry has grown it has become dominated by a few very large firms, so that today about 57 percent of the global retail market in chocolate confectionary is controlled by five firms (Cadbury, Mars, Nestlé, Hershey, and Ferrero), and in the United States about 75 percent of the candy rack is owned by Hershey and Mars.

Unfortunately, having so much power concentrated in the hands of a few major players has meant that the farmers who grow the cocoa beans have little bargaining power and are not particularly well served.[10] For example, the price of cocoa on the global market in 2018 was less than half the price it had commanded forty years earlier, though it rose sharply in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[11] Although the chocolate industry began to embrace practices consistent with TBL management starting around 1990,[12] nevertheless in West Africa (where Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana provide most of the world’s cocoa), many plantations use slaves and there are up to 2 million child laborers, with the typical cocoa producer earning only $1/day on average.[13] (That average wage could be doubled by increasing the retail price of a chocolate bar by 7 percent.)[14]

Chocolate as an opportunity for SET businesses: The Divine Chocolate Company was founded in 1998 and deliberately structured so that its cocoa producers would own 33 percent of the company, have representatives on the board of directors, and be guaranteed a fair price for their chocolate.[15] Even in 2024, it was the world’s only fair trade and farmer-owned chocolate company.[16] More precisely, Divine is co-owned by a Ghanaian cooperative called Kuapa Kokoo, a group of 85,000 cocoa producers from over 1,200 villages who collectively sell about 5 percent of their cocoa to Divine. A cooperative is an organization that is owned and democratically run directly by its members, in this case the cocoa farmers themselves (see Chapter 6). In addition to purchasing their cocoa for a fair price, Divine helps its farming co-owners to address issues like child labor and climate change, and together they have invested about $3 million in medical clinics, water wells, and schools throughout Ghana. Perhaps Divine’s most important contribution has been as a force in the marketplace that compels mainstream businesses to begin to purchase cocoa at fair prices. For example, when Cadbury decided to source all its Ghanaian chocolate from certified fair trade suppliers, this doubled the amount of fair trade sales for the Kuapa Kokoo farmers (for more on fair trade, see Chapter 5).[17]

2.1. Introduction

The idea of studying management in business schools is barely a century old, yet today management has become among the world’s most popular courses in colleges and universities. Although management is an essential feature of modern life, we often forget that our understanding of management is relatively new, and that it is a subjective, socially constructed concept.[18] The social construction of reality occurs when something is perceived to be an objective reality and people allow it to shape their thinking and actions, even though its meaning has been subjectively created by humans and must be constantly recreated by humans in order to continue to exist. For example, a $100 bill is just a small piece of plastic polymer; it only has value because we all agree to treat it as valuable. Similarly, the meaning of “management” was invented and is constantly being re-invented by people who, like us, live in a specific social context. Just as the meaning of chocolate has changed over the past 4,000 years, the opening case describes, so also has the meaning of management.

To illustrate the importance of studying the history of management and how it is a socially constructed concept, we can look at how other socially constructed ideas have changed over time. For example, consider how the meaning of being a woman or a man has changed. Not so long ago, women were treated as objects owned by men. Three or four generations ago, American women did not have the right to vote, but now it seems impossible to believe that women should not vote. Likewise, the wage gap between men and women has been narrowing over time: since 1970, women’s pay as a percentage of men’s has increased from around 60 percent to around 80 percent in the United States. Indeed, the fact that Time magazine named the #MeToo movement as the “person of the year” in 2017 highlights how the meaning of gender continues to change.[19] In the same way, the social construction of what it means to be a manager has also changed over the years and should be expected to change in the future.

In this chapter, we begin with an examination of how for most of the history of humankind, people’s understanding of management was more aligned with a Social and Ecological Thought (SET) approach than with the Financial Bottom Line (FBL) or Triple Bottom Line (TBL) approaches. We then describe various events that, taken together, created the foundation for the development of FBL management, the formal study of which became popular about 100 years ago. After this brief look at history, we describe the twentieth-century development of the contemporary functions of management (planning, organizing, leading, and controlling), the transition to the TBL approach starting in the 1990s, and signs of a transition to the SET approach starting around 2010.

As you read this chapter, keep in mind that every way of seeing management is also a way of not seeing management. For example, if we understand management as being primarily about maximizing financial well-being, then other forms of well-being become secondary and subservient. But if we see management primarily as a way of improving social and ecological well-being, then it cannot be primarily about maximizing profits. By saying or believing that management is about something, we implicitly say and believe that it is not about something else.

2.2. Five Eras of Pre-Contemporary Management Thought

2.2.1. Pre-Humankind (13,700,000,000 BCE)

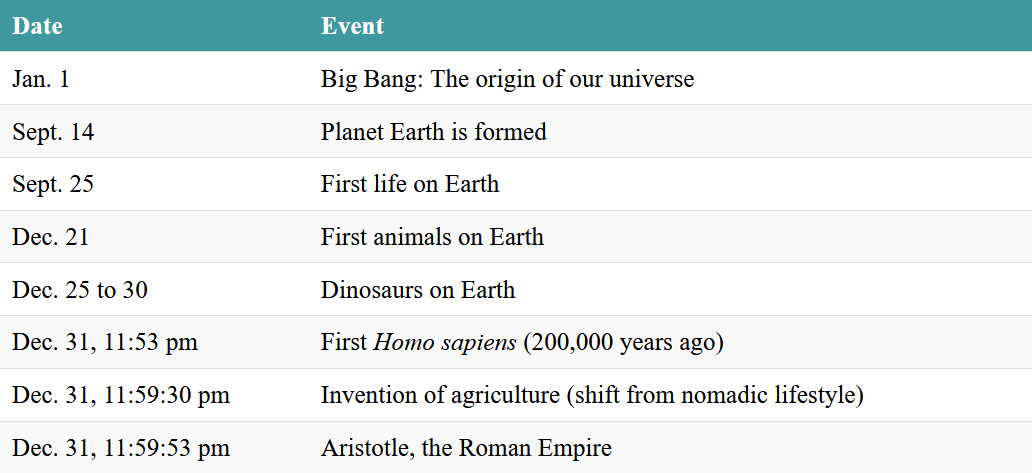

Because we tend to live in the “here and now,” we often forget that humankind constitutes a very small part of the cosmos, and many scientists suggest that the cosmos is about 13.7 billion years old. Imagine that we were to compress the history of the cosmos down to one calendar year. That is, imagine that the Big Bang was the first thing that happened on January 1, and that we are living in the final second of December 31.[20] Table 2.1 shows the timing of some noteworthy events on such a cosmic calendar. In short, humankind has been around for less than ten minutes, and one may wonder if we will still be here a minute from now. Or perhaps we will last five days, like the dinosaurs.

Table 2.1. Noteworthy dates on the cosmic calendar

Although many factors helped to create the conditions that have enabled humankind to exist and thrive as a species, we will highlight just three: the sun, carbon, and plankton (these will be elaborated upon in Chapter 4). First, the sun’s life-giving energy has shaped—and in this way has managed—the life forms on the planet.[21] Second, carbon is considered by scientists to be “the currency of life,”[22] or the building block of life, because it is found in every plant and animal in the food web.[23] Third, phytoplankton—microscopic photosynthetic organisms that live in the oceans and represent the bottom of the food chain in our oceans (a drop of seawater contains up to 5,000 phytoplankton[24])—were critical in creating the atmosphere that permits humans to breathe, and they still provide half of the planet’s supply of oxygen[25] and absorb about 25 percent of the carbon that humankind sends into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels.[26]

In sum, the life forces of the cosmos have helped to shape and give rise to humankind. Although it may be tempting to construct a social reality that suggests, for example, that humans can “own” land or other natural resources, in reality it is Earth and its natural systems that has given rise to and owns humankind.

2.2.2. Hunting and Gathering (40,000 BCE)

Scientists are not sure when humankind’s ancestors first walked the planet; it may be as long as six million years ago, and people who, anatomically speaking, looked like modern Homo sapiens have been around for up to 200,000 years.[27] But the idea of human culture dates back to about 40,000 to 80,000 years ago, when we find the earliest evidence of people thinking symbolically (i.e., in pictures and words),[28] and thus able to manage and organize the production of goods and services. This ability to think symbolically enhanced the development of language and the ability to communicate information from one generation to another.[29]

For the vast majority of its history, humankind lived a nomadic lifestyle in tune with the natural world, influenced by its natural rhythms and seasons, such as the migratory behavior of the animals we hunted.[30] Organizational structures and systems were simple, and people lived mostly in organizational units we call clans (e.g., forty people who traveled the land together), and each clan collectively produced the goods and services members needed to survive.

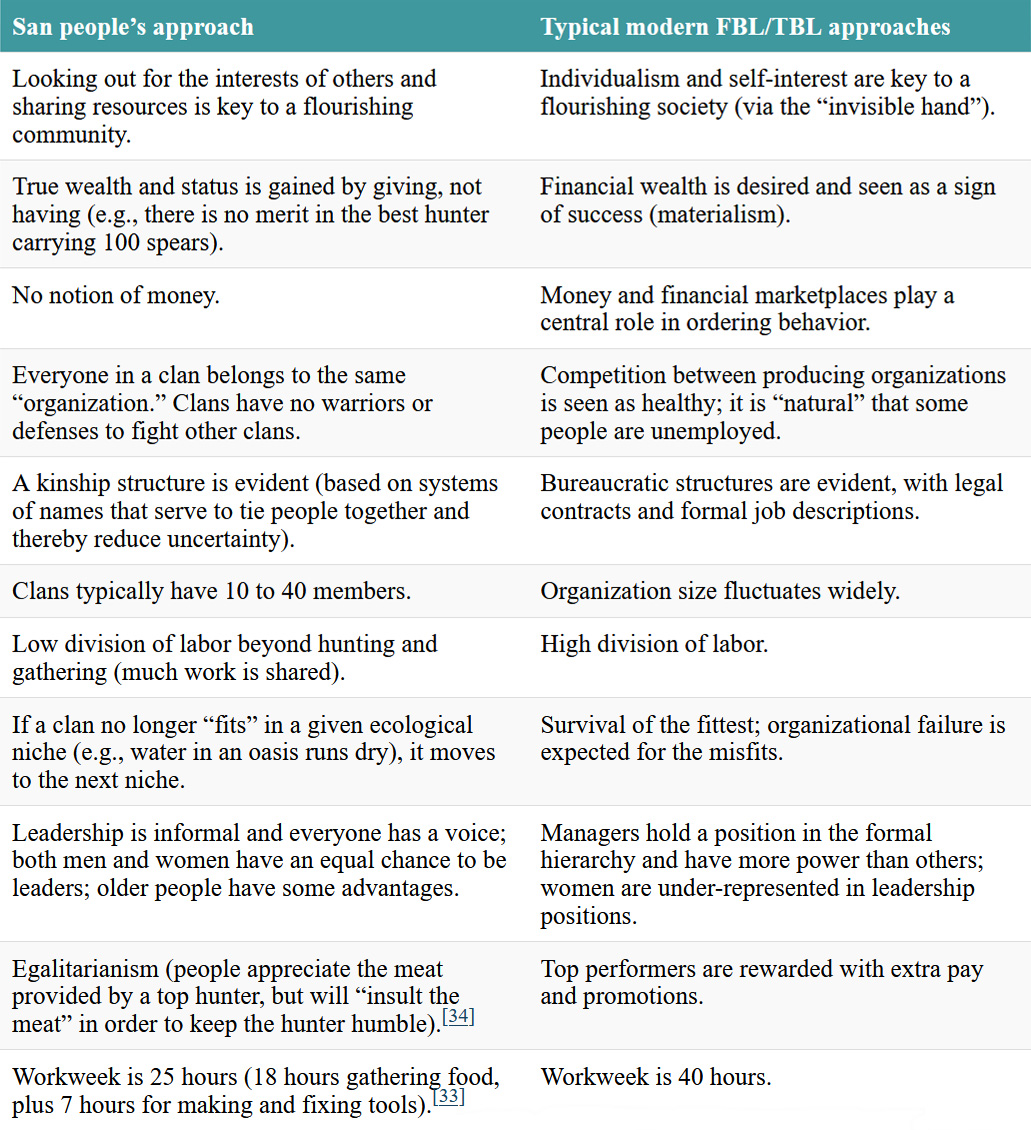

We do not have much information about what management looked like during the time when humans were foragers, but we might be able to get a sense of it by studying the structures and systems of the few remaining peoples on the planet who still live as foragers.[31] For example, the San people who live in the Kalahari desert occupy land that is so meager that it remains unattractive for modern agriculture or commerce, and the San are thus still foragers like their ancestors from millennia ago. Table 2.2 compares their values and ways of organizing with contemporary values found in high-income countries.[32]

Table 2.2. Forager vs. modern values and ways of organizing

2.2.3. The First Agricultural Revolution (starting 10,000 BCE)

About 12,000 years ago, humankind started to learn to reliably domesticate animals and plants. This resulted in the ability to establish settlements, which over time also allowed for the development of new social institutions. For example, because the time spent hunting and gathering was reduced, people had time to develop languages and the arts. Domestication also led to surpluses and specialization, which eventually fostered economic trade between settlements. Coupled with the idea of property ownership, surplus and trade led to the deepening of social hierarchies, with an increasing differentiation between social classes. The accumulation of wealth and specialization also led to the creation of militaries, in response to people who felt the need to protect their resources (and potentially to seize the resources of others). In combination, growing specialization, surplus creation, wealth, and trade all created the need for management.[35]

Test Your Knowledge

2.2.4. The Advent of Money (starting about 1500 BCE)

The first coinage appeared around 1500 BCE, and by 500 BCE Aristotle was distinguishing between what he called the “natural” vs. the “unnatural” management of money.[36] The natural management of money refers to enhancing overall well-being by using money to facilitate the transfer of valued goods in a community-sustaining way and is associated with sustenance economics (see Chapter 3).[37] It is evident when, for example, a woman brings tomatoes to her village marketplace hoping to come back with a pair of sandals. She sells her tomatoes to a customer for a fair price and buys her sandals from a seller for a fair price. Such interactions and relationships foster what Aristotle calls “true wealth” in communities, evident in all stakeholders creating and obtaining valued goods in a fair and sustainable manner (consistent with SET management).

In contrast, according to Aristotle, the unnatural management of money refers “to maximizing financial well-being by using money to make money,”[38] and is associated with acquisitive economics (see Chapter 3). It is evident when a woman brings money to a marketplace, purchases tomatoes from a vendor in order to sell them in turn to a customer at a higher price, thus making a financial profit. While the act of buying and selling tomatoes in both examples may appear to be identical, unnatural transactions create what Aristotle calls “spurious wealth,” because these transactions do not involve the creation of any goods or services (e.g., no new sandals are manufactured, and no new tomatoes are grown).[39] Aristotle goes on to lament how managing to create competitive advantage and monopolies can enable people to use money to make more money in ways that are not good for overall societal well-being. The natural use of money has inherent stopping points where the purchaser is satisfied (e.g., one can only eat so much food; one can only wear one pair of shoes at a time), whereas the acquisition of money for its own sake does not.[40] The growing importance of wealth, both its creation and its management, increased the need for professional managers.

2.2.5. Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution (1500 CE)

About 500 years ago, important social changes fostered the advent of capitalism, an economic system based on rewarding entrepreneurs for profitably combining resources in ways that create valued goods and services.[41] With its emphasis on financial rewards for individual entrepreneurs, capitalism would have been unthinkable as a mainstream economic paradigm prior to the 1400s, when economic systems were generally based on one or more of the following three principles: reciprocity (neighborliness, trading with one another); redistribution (ensuring that everyone has enough, which might involve a central entity like a tribal leader or feudal lord collecting and redistributing resources to others); or householding (being a good steward of resources for the sake of the family or larger community).[42]

Max Weber, perhaps the most influential scholar in the field of management and organization theory,[43] argues that the hallmarks of capitalism—its emphasis on financial rewards (materialism) for entrepreneurs (individualism)—arose during the religious reformation in Europe that started around 1500 CE. At this time, people’s beliefs about how God wanted them to live began to change. First, rather than focusing on sharing resources so that everyone had enough, people began to see financial wealth as a blessing from God and considered more wealth to be evidence of greater blessings.[44] Second, rather than prioritizing the importance of the larger community and its interests, people began to focus on their own personal calling and interests. Taken together, this led to an emphasis on materialism (placing a high value on physical possessions, financial well-being, and productivity) and individualism (placing a high value on self-interests).[45] Although there have long been individuals and groups who pursued selfish material gain, this was the first time that the ideas of individualism and materialism became widely accepted in society, and this change marked the first time in human history that the dominant economic system was based on the principle of individual economic gain.[46]

Taken together, the legitimation of materialism and individualism, coupled with Adam Smith’s ideas about the “invisible hand” growing the economic pie, went a long way in laying the foundation for FBL management and a new kind of entrepreneurial activity that ushered in the Industrial Revolution (1760—1840). During this time, businesspeople were very successful in increasing productivity, creating material goods, and growing the economy. Moreover, they were well rewarded financially for their successes. The Industrial Revolution was a time when factories were built and technology developed so that, for example, the productivity of textile workers increased 1,000-fold thanks to advances like cotton-spinning machinery coupled with steam-engine technology. There were also other changes in supporting institutions—such as banks enabling the use of checks—and, of course, increased capacity in using fossil fuels. These changes also hastened international trade and colonialism, leading to what has been called the first era of colonialism and free trade.

Increase in Size and Power of Organizations

These changes led to growth in the size of businesses. Until a couple of centuries ago, most organizations were small; many were family businesses or owner-managed firms where workers could easily see how their specific job fit into the whole operation. Adam Smith’s description of a pin factory, published in 1776,[47] provides what is perhaps the best single description of the shift toward people working in factories and away from working in small businesses that were family owned and operated. Smith demonstrated the merits of specialization and the division of labor by describing how four workers, each performing a specialized task, could produce 48,000 pins per day instead of the less than twenty pins per day that each worker might have produced working independently and performing all the tasks. In other words, specialization increased those four workers’ productivity approximately 1,000-fold. By organizing work in large factories—rather than in small, home-based businesses—productivity could be dramatically increased. Smith’s analysis was compelling and reflected how the Industrial Revolution was changing where people worked (factories) and the type of work they did (highly specialized and repetitive tasks).

This era also saw changes in the legal form of business, in particular with the rise of the corporation, a business that enjoys many of the privileges and legal rights of a person, is considered by law to be an entity separate from its owners, and where the financial liability of its owners is limited to the value of their investment in the firm.[48] For centuries it was very difficult to get a charter to start a corporation, except for special large-scale projects that were clearly in the public interest and could not be completed otherwise (e.g., corporations were given charters expressly for the building of canals, turnpikes, and other public infrastructure). Even in the United States, there were only several hundred corporations at the beginning of the 1800s. At the time, citizens were wary that corporations (domestic or foreign, for-profit or not-for-profit) might inhibit their newly won democratic freedoms. As Paul Hawken writes, “Citizens openly and presciently expressed concern that corporations with specific rights granted under the charters would nevertheless become so powerful that they could take over newspapers, public opinion, elections, and the judiciary. . . . Some states even required public votes to continue certain [corporate] charters.”[49]

Since the Industrial Revolution, corporations have gained more power and become more prevalent,[50] but there remain ongoing concerns about whether they have too much power.[51] The influence of corporations on government policy and social thought continues to grow through advertising, lobbying, and think tanks. For better or worse, we have come a long way from the original corporate idea of “limited liability” that was intended to support building public infrastructure projects to enhance the common good.

Test Your Knowledge

2.2.6. Summary of the Pre-contemporary Management Eras

The development of contemporary management thought did not occur on a blank slate. Rather, it emerged within a specific set of physical and social resources and assumptions that were in place prior to 1910. In particular, important assumptions and ideas were in place in 1910 that would have been inconceivable for most of the history of humankind:

- the idea of private property and that natural resources are subservient to the wishes of humankind;

- the idea that it is praiseworthy to use money to make more money;

- the idea that it is natural for humans to be materialistic and individualistic;

- the idea that capitalism is the best way to organize economic activity; and

- the idea that society is well served by having an increasing amount of its goods and services provided by large and powerful profit-maximizing corporations.

Of course, as we noted at the beginning of this chapter, all of these ideas are socially constructed and only remain “true” as long as people believe in and perpetuate them.

Test Your Knowledge

2.3. Six Eras of Contemporary Management Thought

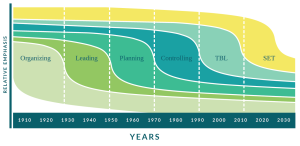

The formal study of contemporary management is about one century old and, as shown in Figure 2.1, can be seen to have evolved in six eras or phases.[52] Each of the first four phases, which are grounded in an FBL approach, corresponds roughly to one of Henri Fayol’s four functions of management—planning, organizing, leading, and controlling—that were introduced in Chapter 1. The fifth phase describes the transition from the FBL to the TBL approach, where managers seek to increase financial performance by reducing negative socio-ecological externalities. The sixth phase describes the start of a movement to SET management, which emphasizes enhancing socio-ecological well-being while ensuring adequate financial well-being.

Of course, this six-phase model is a simplification, and within each phase there is evidence of research and practice associated with the other phases. Even so, there are identifiable changes over time in the relative emphasis placed on different aspects of management. In the sections that follow, we describe the essential features of each of these eras.

Figure 2.1. Simplified overview of relative emphases in management

2.3.1. The Classical Era (1910–1930): Emphasis on Organizing

The classical era of contemporary management can be subdivided into two separate schools of thought, one with a micro focus (looking at how to design specific jobs) and the other a macro focus (looking at how all the different jobs fit together in an organization). The first, scientific management, focuses on determining the best way to carry out specific jobs via designing the optimal process for performing a job, selecting people with the required abilities, training them to improve their efficiency, and developing reward systems that will optimize productivity. The second, bureaucratic organizing, emphasizes the design and management of organizations on an impersonal, rational basis via methods like clearly defined lines of authority and responsibility, formal record keeping, and rule-based decision-making.

Scientific Management

Frederick W. Taylor (1856–1915) is often called “the father of scientific management.” His philosophy is captured in this statement: “In the past man [sic] has been first. In the future, the system must be first.”[53] His most famous study describes how scientific management helped to increase the shoveling productivity at a Bethlehem Steel plant in Pennsylvania. Rather than have workers bring their own shovels to the plant, as had been the custom of the time, Taylor carried out studies to determine the best-designed tool for each task, which included different shovels for different types and weights of materials being shoveled. After managers provided workers with optimally sized shovels, the average output per worker increased almost 280 percent, from 12.5 tons per day to 47.5 tons per day. At the same time, workers’ pay increased about 60 percent, from $1.15 per day to $1.85 per day.[54] This was seen as a “win-win” situation, and Taylor’s ideas and methods quickly spread throughout industry.[55]

There were other important contributors to the scientific management approach. Henry Gantt (1861–1919) developed the Gantt chart, a bar graph that managers could use to schedule and allocate resources for a production job.[56] The Gantt chart is still used today to plan project timelines. It identifies various stages of work that need to be completed, sets deadlines for each stage, and monitors the process. This helps managers to determine in advance when and where workers will be needed in throughout the production process.

Another important contributor was Frank B. Gilbreth (1868–1924),[57] who worked independently from Taylor to develop time and motion studies, which precisely measure how long it takes to perform a task in different ways, and use these data to identify the best way to do a task. Gilbreth is known for his emphasis on efficiency and his quest to find the “one best way” to organize work. For example, his analysis of bricklayers resulted in simplifying the bricklaying process from eighteen different motions down to five, which resulted in a 200 percent increase in productivity. Gilbreth’s pioneering work in time and motion studies inspired such innovations as foot levers for garbage cans, aided in the design of ergonomic products and practices, and improved modern surgery techniques.[58]

Bureaucratic Organizing

Max Weber (1864–1920) developed ideas about bureaucratic organizing from observing how to manage organizations in ways that are formally rational (that is, managed according to impersonal efficiency-maximizing rules).[59] Before Weber, the traditional ways of organizing included an emphasis on providing jobs for relatives and friends. These old ways were replaced by a more professional way of organizing that focused on employee competence, where managers used their positional authority and skills to design and implement rules and procedures that would result in efficient and productive structures and systems. Weber’s rich theory and conceptual frameworks continue to underpin contemporary management and organizational theory.

Another important scholar who contributed to the classical era was Henri Fayol (1841–1925), with his ideas about administrative management. In addition to giving us the four functions of management, described in Chapter 1, Fayol developed several principles of management, including the unity of command principle, where each employee reports to only one superior, and the scalar chain, which says that an organization should have clear lines of authority that extend from the top to the bottom of its hierarchy and include every employee.

In sum, scholars in the classical era contributed to our understanding of how the organizing function is managed, that is, how to ensure that tasks have been assigned and a structure of organizational relationships created that facilitates meeting organizational goals. Other scholars soon discovered the importance of complementing this technical focus on organizing with a better understanding of how to manage the human side of organizations. The key scholars and studies that ushered in this new era of management are described below.

Test Your Knowledge

2.3.2. The Human Relations Era (1930–1950): Emphasis on Leading

If Frederick Taylor is considered the father of scientific management, then Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933) is the mother of the human relations era. Follett’s emphasis on the human (rather than the technical) side of management was in stark contrast to the scientific management school and its emphasis on impersonal bureaucratic structures.[60] Follett argued that authority should not always belong to the person who formally holds the position of manager, but rather that power should be fluid and flow to workers whose knowledge and experience makes them best suited for a particular task or situation.

Follett studied how managers actually perform their jobs by observing them in their workplaces. In arguing that managers should facilitate the work of subordinates rather than try to control it, Follett diverged from the organization-as-machine ideas of the classical era. For her, leadership was defined not by top-down control and the exercise of power but rather by the ability to increase the sense of power among followers.[61] She viewed organizations as communities where managers and workers should work in harmony without one dominating the other, and where each had the freedom to discuss and resolve differences and conflicts. Follett’s behavioral approach, which drew from sociology and psychology to help managers see the benefits of viewing people as a collection of beliefs and emotions rather than as cogs in a machine, was far ahead of its time.

Lillian Gilbreth (1878–1972) also made substantial contributions to the field of human resource management.[62] She studied ways to reduce job stress, championed the idea that workers should have standard workdays, and influenced US Congress to establish child labor laws and develop rules to protect workers from unsafe working conditions.[63]

Another important early proponent of the view that people were important in organizations was Chester Barnard (1886–1961), an executive with AT&T and president of New Jersey Bell Telephone. He drew attention to the importance of leadership and the informal aspects of an organization, pointing out that all organizations have informal social groups and cliques that form alongside their formal structures. In his view, organizations were not machines and could not be managed effectively in the impersonal way implied by scientific management theory.

The Hawthorne Effect

Another important contribution to the transition from the organizing to the leading era came from Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger, who worked on a research project originally sponsored by General Electric.[64] Consistent with ideas of the organizing era, the company wanted to sell more light bulbs by demonstrating to potential business customers that the productivity of factory workers would increase with improved lighting. However, the research that took place in one particular location, the Hawthorne, Illinois, plant of the Western Electric Company, provided some startling results.

The research design took the form of a field experiment in the tradition of scientific management. The five independent assembly lines in the Hawthorne plant were divided into two groups: a control group, which consisted of three assembly lines where the amount of lighting stayed constant; and an experimental group, which was a separate room with two assembly lines where the amount of lighting was systematically varied. Researchers monitored workers in both the control and the experimental groups. As expected, productivity increased in the experimental group when lighting was increased. However, productivity also increased in the control group at the same time. Indeed, productivity increased in both groups regardless of whether the amount of lighting in the experimental group went up or down. Productivity finally decreased for the experimental group when lighting was dimmed to the level of moonlight or twilight. Not surprisingly, General Electric withdrew its sponsorship of the study![65]

This research led to a number of follow-up studies and became famous with a popularized understanding of the Hawthorne effect, which suggests that giving workers special treatment increases their productivity.[66] More generally, the Hawthorne effect suggests that knowing they are in an experiment will influence the behavior of subjects. To modern ears, the idea that employees’ productivity might be affected by how they are treated by managers may sound pretty obvious, but at the time it helped to move management thought from the classical era to the human era. This is not to suggest that organizing was no longer important, but that scholars began to place increased emphasis on the human element in organizations.

The Human Relations Movement

The results of the Hawthorne studies led to the human relations movement, which focused on managerial actions that would increase employee satisfaction in order to improve productivity. The human relations movement has been described as the “happy cow” approach to management: just as contented cows give more milk, satisfied workers will be more productive. Unlike the scientific management movement, the human relations movement placed emphasis on managers using social skills to motivate employees, and on designing jobs that would be more humane, more interesting, and less fatiguing.

One of the best-known early contributions of the human relations perspective was developed by Douglas McGregor (1906–1964), who differentiated between two types of managers based on their assumptions about employees.[67] Theory X managers assume that people are inherently lazy, dislike work, will avoid working hard unless forced to do so, and prefer to be directed rather than accept responsibility for getting their work done. Theory X managers therefore design structures and systems that will ensure people work hard. This may take the form of introducing control systems, setting the pace with assembly lines, implementing piece-rate pay systems, and threatening to lay off workers who fail to work hard enough. McGregor argued that Theory X assumptions reflect a classical approach to management.

McGregor proposed that managers should adopt Theory Y assumptions, which he considered to be a more realistic (and better) approach to management practice. Theory Y managers assume that work is as natural as play, that people are inherently motivated to work, and that people will feel unfulfilled if they do not have the opportunity to work and thereby make a contribution to society. Theory Y also assumes that workers prefer to have as much control as possible over their own work, and that people will gladly take responsibility for their work so long as there are adequate structures and systems in place to facilitate their doing so. Thus from a Theory Y perspective, the challenge of management is to provide the support necessary to allow people to excel at their work. This may be accomplished by allowing them to set their own pace for their work, providing opportunities to work in teams, implementing profit-sharing plans, investing in ongoing training and development for workers, and providing a sense of long-term commitment to workers. McGregor argued that this Theory Y approach would maximize productivity.

In sum, where the first era of contemporary management practice laid the groundwork for understanding the importance and role of the technical side of management, the second era did the same for the people side. Taken together, the work of trailblazing scholars in the first two eras provided the foundation for an upsurge in research on organizations that started around 1950, with a focus on elaborating upon the groundbreaking insights of the earlier eras. As the importance of organizational management in society became more evident, more and more universities started to emphasize studies in this area.[68]

2.3.3. The Calculating Era (1950–1970): Emphasis on Planning

During World War II there was a need to improve industrial productivity to aid the war effort, and also a need to develop new techniques to manage the war effort. The British, for example, assembled mathematicians and physicists into teams that analyzed the formations, routes, probable locations, and speed of Nazi submarines. These war-related efforts laid the groundwork for management research on planning and strategic decision-making. For example, after the war, lessons learned about deploying troops, submarines, and other equipment were adapted and applied by managers at General Electric to decide where to deploy employees, locate plants, and how to design warehouses. Three different subfields have emerged to aid in managerial planning and decision-making: management science, the systems approach, and contingency theory.

Management Science

Management science uses the tools of mathematics, statistics, and other quantitative techniques to inform management planning, decision-making, and problem solving. Management science is sometimes seen as having two areas: operations research draws on mathematical model building to explain and predict outcomes,[69] while operations management uses quantitative techniques to help managers make decisions that allow organizations to produce goods and services more efficiently. Management science includes the following:

- break-even analysis (e.g., to determine the sales volume and prices required to earn a profit, which product lines to keep and which to drop, and prices to set for products and services);

- forecasting projections (e.g., to help set production targets and decide whether and when to expand production facilities);

- inventory modeling (e.g., to help managers decide on the timing and quantity for ordering supplies to maintain an optimal inventory, and how much end-product inventory to keep on hand);

- linear programming (e.g., to help determine how to allocate scarce resources among competing uses);

- simulations (e.g., mathematical models that test the outcomes associated with making different decisions).

The Systems Approach

The systems approach recognizes that the elements that comprise and affect organizations are interrelated in complex ways—where each element may be both a determinant and a consequence of other elements—and offers conceptual tools to understand and address problems that cannot be solved by intuition, straightforward mathematics, or simple experience. In particular, the systems approach draws attention to the importance of managers’ looking beyond their organization’s boundaries.[70] In systems language terms, rather than look at an organization as a closed system, managers should adopt an open systems perspective. The closed systems view looks at managing activities as though the organization were a self-contained and self-sufficient unit. The primary attention is on activities within an organization’s boundaries. A manager who views her pizza restaurant as a closed system will focus on the activities happening within the walls of the restaurant (e.g., friendly customer service, cleanliness in the kitchen, adequate staff training, and so on).

The open systems view emphasizes the organization’s place in the larger environment, and how the organization takes inputs from the environment and transforms them into outputs that go into the environment. A restaurant manager with an open systems perspective will be more aware of where to recruit staff, how to advertise for specific target markets, which suppliers to choose, and so on. Thus, managers who adopt an open systems perspective are aware of their organization’s place in the larger environment and their dependence on that environment. Organizations require access to inputs (e.g., raw materials, labor) and a market (e.g., customers) for their outputs, all of which exist outside the organization in the broader environment.

Managers who adopt an open systems view are more likely to realize synergy, which occurs when the performance gain that results from two or more units working together—such as two or more organizations, departments, or people—is greater than the simple sum of their individual contributions. By contrast, managers who adopt a closed systems view are likely to experience entropy, the natural tendency for a closed system to fail because it is unable to acquire the inputs and energy it requires.[71] Some aspects of systems theory are also evident today in subfields like management information systems and total quality management (see Chapter 18).

Contingency Theory

Advances in quantitative methods and open systems theory helped to refine the planning and decision-making processes that are central to managers’ jobs. However, both perspectives still perpetuated the view that managers could find the “one best way” to manage and to make decisions. Two developments in the field served to challenge this idea that there was one best way. First, Herbert Simon—who won a Nobel prize for his insightful research—argued that managers are rarely able to recognize or choose the best way because of bounded rationality, the tendency to make suboptimal decisions because individuals lack complete information and have limited cognitive ability to process information (this will be discussed further in Chapter 7).[72]

Second, contingency theorists argued that there is no single best way to manage, because the best way will change based on the situation. In particular, contingency theory suggests that the best way to manage a specific organization depends on, and is determined by, identifying the optimal fit between its structure, culture, environment, technology, and strategy. For example, as will be discussed further in Chapter 11, to optimize productivity, managers should develop many written rules and procedures if their organization operates in a relatively stable environment. But managers should have fewer organizational rules and prescribed operating procedures if their organization operates in a more volatile environment.[73] In short, the best way to manage depends in part on the environment.

2.3.4. The Values and Beliefs Era (1970–1990): Emphasis on Controlling

The values and beliefs era grew out of the 1960s, a decade that produced remarkable technological and large-scale organizational accomplishments such as space travel and walking on the moon. At the same time, the 1960s was also a time of “flower power” and questioning the status quo. It is in this context that the study of management saw a heightened interest in the role of values and beliefs within organizations, which play a fundamental role in the controlling function. Recall from Chapter 1 that controlling refers to ensuring that the actions of organizational members are consistent with its values and standards.

The Social Construction of Reality, Institutionalization, and Managers

In this era, scholars became more interested in how people’s behavior is controlled by the socially constructed “scripts” that have been learned over time, noting that these scripts are especially powerful and difficult to change in organizational settings.[74] Scripts are learned guidelines or procedures that help people interpret and respond to what is happening around them.[75] People learn scripts for a variety of settings, from knowing what to do and say when meeting new people, to proper table manners and etiquette, to driving a car. Recall that the main idea behind the social construction of reality is that much of what we experience as “real” has actually been created by humans.[76] For example, our attitude to money is based on everyone agreeing on scripts regarding what money is (e.g., money can be used to buy stuff, it is a source of status).[77] Or to refer to this chapter’s opening case, what is the “real” meaning of chocolate: a sacred plant, a medicine, an alternative to alcoholism, an addictive snack food to make profits, or a way to empower farmers in low-income countries?

Once scripts have been developed and well accepted, they can be very useful for the further development and smooth functioning of a way of living. Indeed, one goal of management education and a textbook like this one is to teach students scripts that can help to improve the management of organizations.[78] We hope readers are not only being trained to learn scripts but also being educated to evaluate the meaning of scripts and acquiring tools to write the new scripts that will be required in their future career.[79]

However, socially constructed management principles can also be dysfunctional and very difficult to change. Specific management principles and organizational practices that may have been very rational when they were initially constructed can, over time, become irrational and dysfunctional via a process of institutionalization, which happens when certain practices or rules have become valued in and of themselves, even though they no longer optimize financial well-being for the organization or for society.[80] A classic example of institutionalization is how the QWERTY keyboard has remained the standard, even though more efficient configurations of letter keys could be developed and made available for use on word processing software.[81]

Institutionalized scripts can act like self-fulfilling prophecies. Self-fulfilling prophecies shape and control people’s actions by channeling behavior in a scripted direction rather than in alternative (possibly more positive) directions.[82] For example, research shows that students who learn only about mainstream economic theory and practice—which is based on expectations of materialism and individualism—tend themselves to become more materialistic and individualistic.[83] In our society, managers have particular influence in creating self-fulfilling prophecies that shape the lives and socially construct the meaning of the social world inhabited by others.[84] This creates additional (moral) responsibilities for managers.

Culture and Transformational Leadership

Socially constructed and institutionalized scripts and self-fulfilling prophecies influence people’s norms and values.[85] Once the importance of values in shaping people’s behavior became better understood, it created interest among scholars and practitioners to see if managers could control an organization’s values to improve productivity and profitability. By the 1980s, organizational culture had become a leading topic of study among management scholars (see Chapter 11). Many influential books and articles were published that talked about the important “symbolic” role of management, and about how the essence of leadership was to create the “meaning” that guides, inspires, and motivates organizational members and engages their values (see more in Chapter 15 on leadership).[86]

Test Your Knowledge

2.3.5. The Sustainable Development Era (1990–2010): Emphasis on the Triple Bottom Line

Shortcomings of approaches like FBL management had been long recognized,[87] but two events in the late 1980s were key triggers that helped to usher in the TBL era, which emphasizes financial, social, and ecological well-being. The first occurred in 1987 with publication of Our Common Future by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), after which the term “sustainable development” became an important part of public discourse.[88] A second, related event was the increased knowledge about the science of climate change that came via the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established in 1988.[89] The IPCC published its first report in 1990, which argued that climate change was occurring as a result of human activity, specifically from the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.[90] Though sometimes criticized,[91] together these organizations’ reports provided two key ingredients necessary for change to occur: (1) an urgent call based on science regarding the need for change (IPCC publications about climate change); and (2) a vision about what the change could look like (WCED on sustainable development).[92]

Leaders in the world business community took note and began to establish new organizations that would help to encourage and develop management practices that are consistent with the TBL approach. This included the CEO-led World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), which “marked the beginning of companies’ embedded implementation of sustainable management goals and practices into strategy and process” (1990), and the Global Reporting Initiative (1990), which established guidelines that have become “the world’s primary framework for reporting on companies’ triple bottom line and have been applied by thousands of businesses.”[93]

The TBL approach grew significantly between 1990 and 2010, in terms of both management practice and theory. For example, by 1999 already 35 percent of the 250 largest firms in the world had issued reports on their socio-ecological performance; by 2011 it was 95 percent.[94] This emphasis on socio-ecological sustainability has continued to grow, and by 2023, 37 percent of the 2,000 largest public and private companies globally had committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2050.[95]

This shift toward the TBL approach is also evident in the development of new management theory.[96] It was during this era that scholars first began talking about the “triple bottom line” perspective, which shows how managers can improve an organization’s financial well-being by reducing negative social and ecological externalities.[97] Another important contribution was the advent of the “natural resource–based view,” which takes a dominant strategy theory from FBL management and demonstrates that businesses can enhance their financial performance by reducing costs associated with negative social and ecological externalities (see Chapter 8).[98]

Along the same lines, this era witnessed unprecedented growth in the area of research into corporate social responsibility, which refers to managers’ obligations to act in ways that enhance societal well-being even if there are no direct benefits to the firm’s financial well-being by doing so. However, note that even with this apparent de-emphasis on financial well-being, the bulk of research in this field nevertheless examines the business case for corporate social responsibility (see Chapter 5).[99] Nonetheless, many leading scholars who had previously made important contributions to FBL management began to embrace the TBL approach.[100] For example, in an article in the Harvard Business Review, FBL management expert Michael Porter argued for businesses to improve their competitiveness and economic performance by creating “shared value,” namely goods and services that address the social and environmental problems perceived to have been caused by an FBL approach to businesses.[101]

This era was also characterized by the flourishing of stakeholder theory, which was born out of the observation that shareholders are not the only groups with a stake in an organization: employees, neighborhoods, customers, suppliers, and future generations are also stakeholders because they are affected by what managers do (see Chapter 9).[102] By the turn of the millennium, “stakeholder” had become one of the most-cited and familiar terms in the academic management literature.[103] A significant event establishing stakeholder capitalism as the mainstream management view occurred in August 2019, when the Business Roundtable issued a new Statement of the Purpose of a Corporation (signatories include 181 of America’s largest corporations). The new statement formally reoriented corporate purpose from a singular focus on stockholders (consistent with an FBL orientation) to a broader mandate that “serves all Americans” with specific commitments to customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and even the natural environment.[104] This public shift in management thinking reflects social trends and, in part, criticisms of profit-centric management practices.

2.3.6. The Emergence of Social and Ecological Thought (2010–present): Emphasis on Social and Ecological Well-Being

The sustainability of approaches like FBL and TBL management and the general idea that humankind can or should grow the economic pie indefinitely have been questioned since at least as long ago as Aristotle’s argument for a “natural” rather than an “unnatural” management of money. Other historical voices that point to ecological shortcomings in approaches like FBL and TBL management include Thomas Malthus’s (1798) observation that Earth has a finite capacity to provide food, Ernst Haeckel’s (1866) emphasis on interdependencies between social and environmental systems, Max Weber’s (1903/1958) lament that humankind was caught in a dysfunctional materialistic-individualistic iron cage, and Aldo Leopold’s (1949) treatise on the land ethic and need for humans to form relationships with the land.[105]

Three events during the TBL era, each related to one of the three bottom lines, can be seen to have triggered the shift toward the SET approach. The first was the infamous global financial crisis of 2008, which at the time made even committed believers in the financial marketplace question whether a profit-maximizing paradigm is indeed good for humankind. It prompted new regulations such as the Dodd-Frank Act that, for example, required brokers providing retirement advice to act in the best interests of their clients rather than seeking to maximize their own profit.[106] The second event coincided with scientists’ proclamation that Earth has now entered into a new geological epoch called the Anthropocene, which refers to the effect of humankind on the planet (and the extinctions it has already caused and is poised to continue to cause).[107] The third event was the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011, which increased awareness of the negative social consequences associated with the increasing gap between the richest 1 percent and the rest (the 99 percent), as well as the role of money in influencing politics. This movement and its leaders helped to increase the minimum wage in a variety of cities and states,[108] and encouraged sixteen state legislatures and over 600 towns in the United States to pass resolutions favoring a constitutional amendment that would ensure the rights of people rather than corporations.[109] Taken together, these three events served to call for a new generation of managers who are convinced of the need for an approach like SET management. For example, a 2012 survey found that about two-thirds of millennials agreed that “businesses make too much profit,” and the same number would prefer a job they love that pays $40,000 a year versus a boring job that pays $100,000.[110]

SET management challenges some of the pre-1910 socially constructed assumptions and ideas that FBL and TBL management are founded upon, namely that natural resources are subservient to the wishes of humankind, that it is praiseworthy to use money to (insatiably) make more money, that it is natural for humans to be materialistic and individualistic, and that society is well served by having increasing amounts of its goods and services provided by large and powerful profit-maximizing corporations.

Such considerations attracted great attention during the COVID-19 pandemic that so radically altered worldwide human affairs. The global health emergency saw prioritization of basic human needs and safety over financial and material acquisition, and the need for cooperation, solidarity, and altruism over competition, individualism, and self-interest. Stay-at-home orders that curtailed business activities contributed to a rare period of declining carbon emissions and had positive effects on wildlife populations.[111] Business commitments to social and environmental causes were also heightened during this period,[112] and some observers suggested the pandemic offered an opportunity to reset priorities, with important lessons on how to manage for a more sustainable future.[113]

However, post-pandemic trends showed a quick return to escalating carbon emissions, worsening climate trajectories, and increased geopolitical tensions. Although early contributions to the development of what we call SET management were evident in the TBL era,[114] in recent years, interrelated (un)sustainability concerns have prompted a growing stream of research that places socio-ecological well-being above the need to maximize financial well-being. This stream of research comes from diverse perspectives, many of which will be referred to in the rest of this book. They include place-based organizing,[115] sustainable intra- and entrepreneurship,[116] the traditional wisdom of Indigenous peoples and from spiritual traditions,[117] insights from quantum physics,[118] research on compassion and the ethic of care,[119] and so on.

Many managers have already embraced the SET paradigm. They can be found in organizations such as Taylor Guitars, Greyston Bakery, Assiniboine Credit Union, Aki Energy, Habitat for Humanity, and Interface, to name just a few that will be described in this book. SET management is also evident in the work and vision of B Lab and its initiatives like Certified B Corporations that work toward a vision of developing a “new economy” where business is a “force for good.”[120] In 2024, B Lab had over 9,000 company members in 105 countries, including businesses like Patagonia (outdoor clothing), Ben & Jerry’s ice cream (a Unilever subsidiary), and Natura &Co cosmetics (the world’s largest and first publicly traded B Corp, with over $4.5 billion in net revenue and 19,000-plus employees in 2023).[121] Other SET managers belong to similar movements like the “economy of communion” and other like-minded communities of organizations.[122] But most SET managers work independently from such umbrella organizations; they are content to march to the beat of a SET drum.

Chapter Summary

- The meaning of management is constantly being socially (re)constructed over time.

- Five eras during the period of pre-contemporary management are of particular relevance for understanding the basic assumptions that supported and informed the development of contemporary management thought:

- (i) The pre-humankind era (starting about 13.7 billion years BCE) saw planet Earth change over eons of time to create the conditions that were required for the development of human life.

- (ii) The hunting and gathering era (starting about 40,000 BCE) was a time when humankind managed its affairs while being very aware of its dependence on nature and the dependence of people on each other.

- (iii) The first agricultural revolution (starting about 10,000 BCE) refers to the period when humankind managed to domesticate plants and animals, and thereby transitioned into population concentrations and the development of language and new social institutions.

- (iv) The advent of money (starting about 1500 BCE) enabled humankind to trade more efficiently and to use money to make money.

- (v) The advent of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution (starting 1500 CE) legitimated the ideas of materialism, individualism, capitalism, and large profit-maximizing corporations.

- The development of contemporary management and organization theory can be divided into six eras, the first four of which were mostly characteristic of the FBL approach:

- (i) The organizing era (1910–1930) saw the development of such basic management concepts like the division of labor, bureaucracy, time and motion studies, and the unity of command.

- (ii) The leading era (1930–1950) drew attention to the importance of the informal organization, treating people with dignity and respect, and developing teams and groups.

- (iii) The planning era (1950–1970) pointed to the importance of managing organizational inputs and outputs and open systems, and laid the foundation for future work in strategic management.

- (iv) The controlling era (1970–1990) drew attention to how managers influence the behavior of organizational members by setting an organization’s basic values, core standards, and culture.

- (v) The Triple Bottom Line era (1990–2010) reflected the desire to profitably address and reduce the negative socio-ecological externalities associated with FBL management.

- (vi) The Social and Ecological Thought era (2010–present) focuses on enhancing socio-ecological well-being in financially viable ways.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- According to the cosmic calendar, humankind has been around for about seven minutes. How much longer do you expect we will be around? Explain.

- Can you think of any unintended negative consequences that come from thinking that humankind can “own” natural resources like land, or that it can patent the DNA of different plants? Explain.

- Philosophers like Aristotle argue that using money to make money is problematic because (a) people have an insatiable appetite for money (so they can never get enough money or own enough resources); and (b) this leads to a widening of income disparity and creates negative externalities. Provide three pros and cons associated with using money to make money.

- Do you think it is part of the natural human condition to be greedy, materialistic, and individualistic? For most of the history of humankind, self-interested wealth maximization was dysfunctional (e.g., imagine a nomadic hunter carrying the most spears and the biggest tent of anyone in the clan) and was seen as a moral vice. What would management theory and practice look like if we assumed people were naturally generous and recognized that their own well-being was enhanced by making sure that everyone had enough?

- We take ideas like corporations for granted today, and we forget that not too long ago many people were concerned about the power of corporations and worried that corporations would have a negative effect on society. If you could, would you make any changes to the power of corporations, or set constraints on what a corporation must do to maintain its charter?

- Do you agree with the argument that our understanding of management has been socially constructed? Can you think of any dysfunctional management principles that have been institutionalized? How might they best be challenged? Explain.

- Is the “one best way” to manage still waiting to be discovered? Explain.

- What sort of workplace would you like your manager to construct for you? What sort of organizational reality will you socially construct for others when you are a manager? Is it a social reality that exemplifies FBL, TBL, or SET management principles?

- The rest of the book will look more closely at the planning, organizing, leading, and controlling functions of management. Which functions are you most and least interested in learning more about? Why?

- What do you want students thirty years from now to be learning about management? What sorts of key events or entrepreneurial events would you like them to be reading about that may have taken place during your career? And, more importantly, what will be your contribution to socially create the reality that you wish for the future?

- In your experience, do most businesses reflect FBL, TBL, or SET thinking? Can you think of specific examples for each? Have you observed changes in management practices that reflect these different views during or following the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Chocolate is the favorite flavor of 52 percent of Americans, followed by vanilla and strawberry (each at 12 percent). ↵

- Chocolate remains one of the most secretive of industries. For example, Mars’s candy-making machinery is designed and run by its own engineers. As with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, few outsiders ever see the inside of a Mars chocolate manufacturing facility. If there is need for an outside worker to fix a problem in the plant, the outsider is blindfolded, escorted to the problem area where their expertise is required, un-blindfolded in order to perform the work, and then re-blindfolded and escorted out. ↵

- Sources for this overview include McMahon, P., & Keane, P. (2023). Chocolate and sustainable cocoa farming. Cambridge Scholars; Brenner, J. G. (1998). The emperors of chocolate: Inside the secret world of Hershey and Mars. Random House; Cadbury. (n.d.) http://www.cadbury.co.uk; Doherty, B. (2005). New thinking in international trade? Case study of The Day Chocolate Company. Sustainable Development, 13(3): 166–176; Lehman, G. (2007, September 7). Socially responsible chocolate: Cadbury Brothers in England’s Victorian era. The Annual Howard Raid Chair Lecture, Faculty Colloquium, Bluffton University, Bluffton, Ohio; History.com editors (2022, August 10). The History of Chocolate. https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-americas/history-of-chocolate; Our story. (n.d.) Divine Chocolate. https://divinechocolate.com/pages/our-story; see also Pucciarelli, D. (2017, March 16). The history of chocolate. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibjUpk9Iagk ↵

- The word chocolate comes from the Mayan word xocolatl, which means bitter water; the Mexican Indian word for chocolate comes from the terms choco (foam) and atl (water). For most of its history, chocolate was consumed as a beverage. The bitter beverage was made from roasted cocoa beans, water, and spices. The cocoa bean also played an important role in the religious lives of the Aztecs, an ancient people who ruled a mighty empire in Mexico around the 1400s and 1500s. They believed that Questzalcoatl, their creator and god of agriculture, had traveled to Earth on a beam of the morning star and carried the cocoa tree from Paradise. Like the Mayans, they also drank the chocolate but added some additional ingredients like honey and vanilla to make it tastier than the Mayans’ recipe. ↵

- Cortés brought cocoa beans to Spain, where they were hidden in Spanish monasteries. They became the secret ingredient in a fashionable drink that only the wealthy and the Spanish nobility could afford. The sources of this ingredient remained secret for almost a century. Spain lost its monopoly on European chocolate in the early 1600s when plantations began to sprout up in other parts of Europe, where chocolate grew in popularity among the well-to-do. ↵

- In those days chocolate was sold in drinking houses. Another Quaker, Joseph Fry, made the first chocolate bar in Britain in 1847. Quakers, also known as the Society of Friends, are a nonconformist and pacifist group that developed in the seventeenth century in protest against the formalism of the established church. Their strong beliefs and ideals motivated Quakers to pursue projects that fostered justice, equality social reform and alleviated poverty and deprivation. ↵

- George Cadbury was clearly interested in facilitating different forms of employee well-being outside of the factory, asking, “Why should an industrial area be squalid and depressing?” ↵

- Cadbury handed over the land and houses to the Bournville Village Trust in 1903 with the proviso that revenues should be devoted to the extension of the estate and the promotion of housing reform. ↵

- Unless otherwise noted, all dollar amounts are in US currency. Chocolate industry data from Statista. Confectionary—Worldwide. Retrieved October 16, 2024, from https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/confectionery-snacks/confectionery/chocolate-confectionery/worldwide?currency=USD; Statista. (2015, November 2). Retail consumption of chocolate confectionery worldwide from 2012/13 to 2018/19 (in 1,000 metric tons). Retrieved January 6, 2018, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/238849/global-chocolate-consumption/ ↵

- Cocoa is produced in forty-seven different countries, mostly within 10 degrees of the equator, where temperatures range between 20 and 32 degrees Celsius (68 and 90 degrees Fahrenheit) and annual rainfall is 150 to 255 centimeters (59 to 100 inches). The largest producer of cocoa is Côte d’Ivoire (1,250,000 metric tons) and the second largest is Ghana (370,000 metric tons). ↵

- “Cocoa decreased 10 USD/MT or 0.52% to 1,895 on Friday January 5 from 1,905 in the previous trading session. Historically, Cocoa reached an all time high of 4361.58 in July of 1977.” Cocoa (2018, January 6). Trading Economics. Retrieved January 6, 2018, from https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/cocoa. Cocoa prices are related to the laws of supply and demand. For example, in the 2003–2004 growing year, 3.5 million metric tons of cocoa beans were produced worldwide, but because this was more than needed, the price dropped by almost 25 percent (ICCO Annual Report, 2003/2004). Between 1998 and 2000, the price dropped by almost one half ($1,236 per metric ton to $672 per metric ton). In many cases the control that large firms have over small farmers has a history that goes back to colonialism, when rich European powers used their colonies overseas to procure cheap raw materials. Even after many of the colonies gained their political independence, little changed for small farmers overseas. They had little bargaining power over the large companies that controlled the chocolate trade, and prices continue to fall. In addition, often the situation was made worse by corruption or mismanagement within the new governments. Moreover, rich nations also use restrictions such as tariff barriers to tax some imports differently than others. For example, importing cocoa beans into Europe is much less expensive than importing cocoa butter, and even less expensive than importing chocolate. This serves to penalize poor countries if they try to add value to raw materials like cocoa beans. ↵

- Since the 1990s, the chocolate industry has been working on expanding sustainable cocoa farming efforts. The World Cocoa Foundation was formed in 2000 and has helped to increase farm incomes by teaching cocoa farmers how to reduce crop loss and costs and how to diversify crops grown for family income. It also helps farmers to organize themselves into cooperatives to sell their cocoa. ↵

- Food Empowerment Project. (2022, January). Child labor and slavery in the chocolate industry. Retrieved October 16, 2024, from https://foodispower.org/human-labor-slavery/slavery-chocolate/ ↵

- Typically, cocoa ingredients represent about 6.6 percent of the retail price of a chocolate bar—non-cocoa ingredients account for about 15 percent, chocolate companies’ costs and profits account for over 50 percent, and over 25 percent goes to the shops who sell the chocolates. Make Chocolate Fair. (n.d.). Niedrige Kakaopreise und Einkommen für Kakaobäuer innen. https://makechocolatefair.org/issues/cocoa-prices-and-income-farmers-0 ↵

- The company was established in 1998 as the Day Chocolate Company. Today their ownership of the Kuapo Kokoo has grown to 45 percent, thanks to a donation of shares by one of the other founding members, Gordon Roddick of The Body Shop. For more information about Divine Chocolate, see Gallo, P. J., Antolin-López, R., & Montiel, I. (2018). Associative Sustainable Business Models: Cases in the bean-to-bar chocolate industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 174: 905–916; Nelson, V., Opoku, K., Martin, A., Bugri, J., & Posthumus, H. (2013). Assessing the poverty impact of sustainability standards: Fairtrade in Ghanaian cocoa. https://fairtradekookboek.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/apiss-fairtradeinghanaiancocoa.pdf; see also Divine Chocolate. (2008). Divine inspiration: Stories from Kuapa Kokoo. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PNVTVx9Lg8g ↵

- Barston, N., (2024, February 3). Exclusive: Divine Chocolate MD Ruth Harding celebrates company’s 25th anniversary. Confectionary Production. https://www.confectioneryproduction.com/feature/46969/exclusive-divine-chocolate-md-ruth-harding-celebrates-companys-25th-anniversary/ ↵

- Fair trade chocolate represents about 2 percent of the global chocolate market and is growing at about 50 percent per year. Growth rate in Europe is 30 percent per year (with 48 percent of fair trade cocoa imported into Europe also being certified organic), and in North America the growth rate is 80 percent per year (with 48 percent of fair trade cocoa imported into Europe also being certified organic). Ecole Chocolat. (n.d.). Learn about organic and fair trade chocolate. Retrieved on January 9, 2018, from https://www.ecolechocolat.com/en/organic-fair-trade-chocolate.html ↵

- The idea of the social construction of reality is described later in the chapter. For now, it is sufficient to note that an institution like management, no matter how objective it may appear to be, is produced and sustained by human activity. It is a paradox that humans are capable of producing an idea like “management” that they then experience as something other than a human. To paraphrase Berger and Luckman: Management is a human product that is perceived as an objective reality and which shapes subsequent thinking about management. See page 61 in Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise on the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books. ↵

- Managers’ values will influence gender parity, with research suggesting that the more liberal-minded managers are, the more gender parity there is in the workplace. Carnahan, S., & Greenwood, B. N. (2017). Managers’ political beliefs and gender inequality among subordinates: Does his ideology matter more than hers? Administrative Science Quarterly, 63(2): 287–322. ↵

- See clip about the “cosmic calendar” from Neil deGrasse Tyson (2014, March 4). Cosmos. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShTxGumvbno; Cordeiro, J. (2014). The boundaries of the human: From humanism to transhumanism. World Future Review, 6(3): 231–239. ↵

- For example, the amount of energy humankind uses in a year is about the same as the sun provides to the planet’s deserts in six hours. Shahan, Z. (2012). “Within 6 hours deserts receive more energy from the sun than humankind consumes within a year.” CleanTechnica. https://cleantechnica.com/2012/04/15/within-6-hours-deserts-receive-more-energy-from-the-sun-than-humankind-consumes-within-a-year/ ↵

- Levin, D. (2012, September 6). Follow the carbon. Oceanus. http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/follow-the-carbon ↵

- As noted by Stephen Hawking, “What we normally think of as ‘life’ is based on chains of carbon atoms, with a few other atoms such as nitrogen or phosphorous . . . . The Earth was formed largely out of the heavier elements, including carbon and oxygen. Somehow some of these atoms came to be arranged in the form of molecules of DNA.” See page 308 in Hawking, L., & Hawking, S. (2014). George and the unbreakable code. Random House. ↵

- Based on observation that there are 20,000 drops in a liter, and up to 10 million phytoplankton in a liter. MintPress News. (2013, January 3). The fabulous history of plankton and why our survival depends on it. http://www.mintpressnews.com/the-fabulous-history-of-plankton-and-why-our-survival-depends-on-it/44732/ ↵

- Daily Mail. (2012, February 17). Are ocean plankton the key ingredient that decides the future of Earth’s climate? http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2102639/Are-ocean-plankton-key-ingredient-decides-future-Earths-climate.html ↵