Part 4: Leading

17. Communication

-

- Learning Goals

- 17.0. Opening Case

- 17.1. Introduction

- 17.2. Identify the Message to Be Transmitted

- 17.3. Encode and Transmit the Message

- 17.4. Receive and Decode the Message

- 17.5. Information Flow from Receivers to Sender

- 17.6. Entrepreneurial Storytelling

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

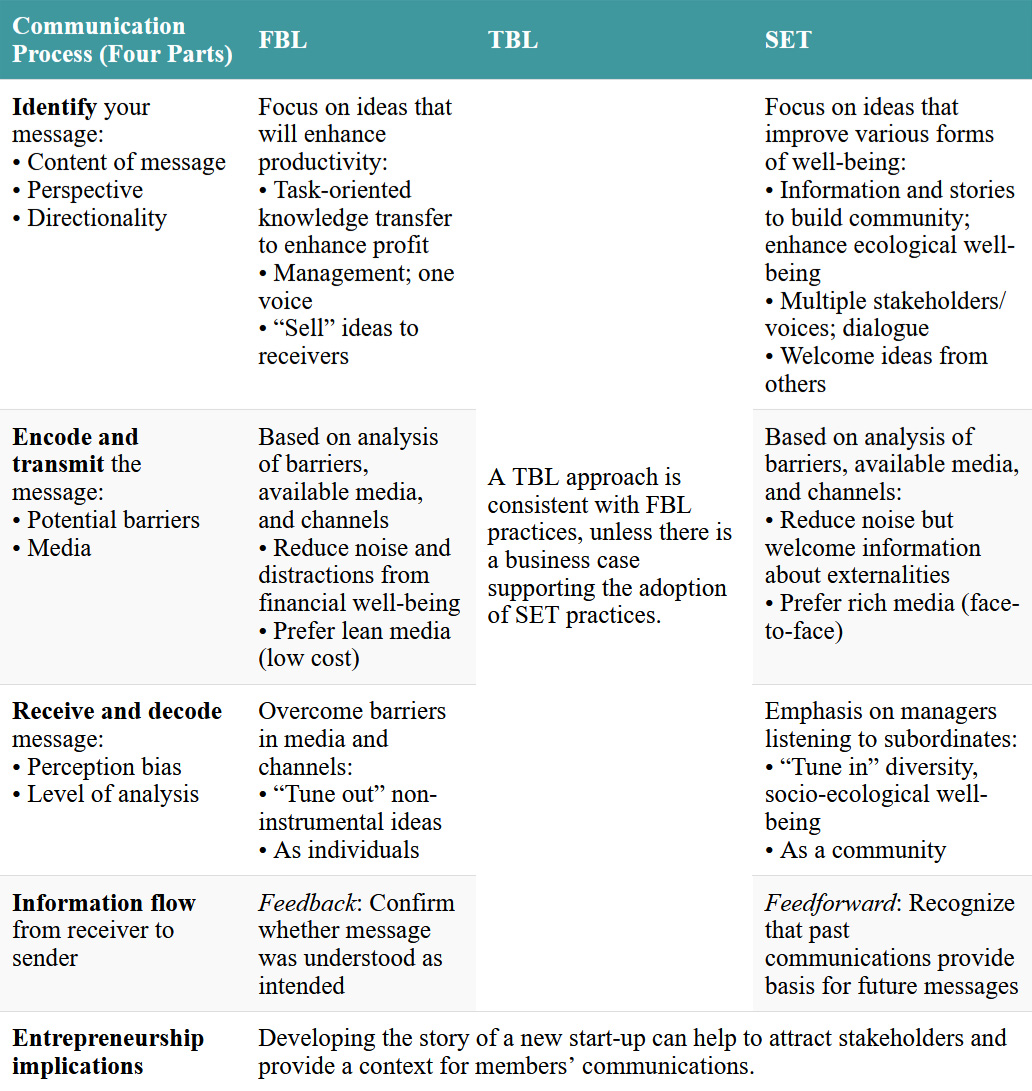

Chapter 17 provides an overview of the four steps of the communication process, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the four generic components of the communication process, and describe differences between the FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to management in each component.

- Describe how messages can vary by content, perspective, and directionality.

- Explain how the encoding of messages involves attending to potential barriers, media, and channels.

- Explain the role of listening and perception biases in decoding messages.

- Describe the difference between treating receiver-to-sender information flow as feedback and feedforward communication.

- Describe how entrepreneurial storytelling can enhance organizational communication.

17.0. Opening Case: A Departure from FBL Management at an Airport

Sandra Montclair had an important message to communicate to others in her organization.[1] As the CEO of Lillum Airport, one of the fifty largest airports in the world, Montclair wanted to change the management of the airport from a traditional top-down style to an approach that emphasized teamwork and participative management. Montclair believed this change would help to improve the airport’s productivity and efficiency, but that was not the ultimate issue for her: “I believed in it in terms of this issue of human dignity.”

Based on a similar change she had implemented at a previous organization, Montclair knew that getting her message across to the several thousand employees at the airport would require a huge communication effort. The communication process started with her top management team of eight, but eventually included all the hierarchical levels in the organization. Montclair had eight managers reporting to her (e.g., terminal manager, cargo manager, commissary manager), who in turn had duty managers reporting to them, who in turn had a host of supervisors reporting to them. For example, the terminal manager was responsible for three duty managers, twenty-two supervisors, and another 450 people below that.

In terms of getting the message out, Montclair knew that she would have a better chance of convincing senior managers of the merits of her planned change in management style if she exposed them to a whole range of experts from other organizations who had implemented similar changes and could talk to them about it. She pulled in a person from the human resource department and invited her senior management team to join her on a journey of learning: “I wanted us all to learn the stuff together.” Of course, the senior managers did not really have a chance to opt out, but Montclair was trying to make it easier for them to opt in and accept her message. She wanted to transmit her message in a participative way, and she wanted to have some fun doing it. So the team went on retreats and conferences together and participated in learning experiences.

In terms of getting people to understand the message, this participative process helped senior managers to understand and agree with the message. They learned from the various speakers and from each other. Moreover, the very process that had been put in place to communicate the message was an example of the new management style, where team members worked together participatively and developed mutual understanding. Even so, feedback showed that further work was required. For example, special training was provided to at least one senior manager who was not aware of his autocratic management style.

After this communication cycle with the senior managers had been completed, a similar process took place at other levels within the organization. For example, the terminal manager went on retreats and learning events with his immediate subordinates. Once the message had been successfully communicated to the members of this group, they would develop plans and procedures for how to implement changes in their areas, figure out how to communicate with the staff, and so on. The terminal manager would then host information events for the rest of his department. This might require three or more sessions to accommodate the 500 members in his unit who were all doing shift work. Montclair explained:

At those information sessions we would say, “Hey folks, we want to run this place differently in the future. This is what the implications we think are for you. This is what we need from you in order to work in this new way. This is what the advantage to you could be.” So we would’ve done that three different times for each of the different departments. So this was a huge communications effort.

These events were often planned alongside day-long sports or barbecue events with a dunk tank and so on, and then there would be opportunity to make speeches, and I would be there to do that. And I would also take my turn in the dunk tank.

The investment in the communication process was worthwhile. Members’ quality of work life improved, as demonstrated by in-house employee surveys of job satisfaction, as did more conventional measures of success: “We had unprecedented performance, in terms of productivity, in terms of on-time departures, reduced line-ups at check-out counters, reduced damaged baggage claims, improved safety.”

17.1. Introduction

Communication is the process of transmitting information via meaningful symbols so that a message is understood by others. In this chapter, we focus on the management of communication among organizational members, especially communication from managers to employees.[2] Communication is a critical part of all four management functions. Managers spend about 75 percent of their time communicating with others.[3] Managers communicate when they design and implement their plans and strategies, when they arrange resources, when they motivate others, and when they design and use information systems. This chapter uses a basic four-part framework to provide an overview of management communication within organizations, describing differences among Financial Bottom Line (FBL), a Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and a Social and Ecological Thought (SET) perspectives.

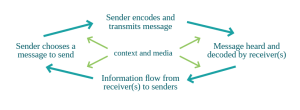

A classic model of the communication process presents it as four basic components that are connected, as shown in Figure 17.1.[4] These four components are traditionally described as unfolding in the following order:

- The sender identifies an idea or a message that is to be communicated.

- The sender encodes and transmits the message.

- The receiver receives and decodes the message.

- Information travels from the receiver to the sender, thus completing the communication cycle and ensuring the message has been understood (or that more clarification is needed).

As depicted by the arrows with dotted lines in Figure 17.1, communication is challenging because moving from one step to the next can be hampered by two basic factors: the overall context in which the communication takes place (e.g., a noisy room) and the media that are used to transmit the message (e.g., an email message does not convey as much information as a face-to-face conversation). In other words, context and media influence each of the four components.

Figure 17.1. Four parts of the communication process

We begin by noting two basic differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to communication, which inform all four parts of the process discussed in this chapter. First, of the three approaches, the FBL perspective has the narrowest range regarding the purpose and content of information being communicated. The purpose of FBL communication is to maximize organizational financial well-being, and the focus is on transferring task-oriented content so that all organizational members will be able to work as efficiently and productively as possible. When the FBL approach includes relationship- and change-oriented information, it does so with an instrumental focus on enhancing financial well-being. The TBL approach embraces a somewhat broader range of information because it is more attentive to communicating with stakeholders about reducing socio-ecological externalities to enhance the firm’s financial well-being. Adding relevant information regarding socio-ecological externalities will increase the range of task-, relationship-, and change-oriented messages being communicated. The SET approach has the broadest range: it shares with the FBL and TBL communication approaches a desire to improve task-oriented operations but adds an interest in enhancing positive socio-ecological externalities. For example, SET management encourages relationship-oriented communications that facilitate achievement of the financial goals of the organization as well as those that develop a sense of community in the workplace and advance meaningful work. Similarly, SET management encourages task-oriented communication that not only contributes to the financial bottom line but also encourages exchanges about a wider array of change options, where financial considerations are secondary to the socio-ecological implications of how tasks are performed.

Second, there is also a fundamental difference in how the three approaches view the communication process as unfolding.[5] A traditional FBL or TBL approach tends to view the four components of the communication process depicted in Figure 17.1 as starting with the sender choosing a message, and then proceeding from there. This is consistent with the traditional description of communication as happening in four sequential steps, and as being a one-way flow of knowledge from sender to receiver (which is confirmed in the final step). In contrast to seeing communication as a one-way flow of information, the SET approach adopts a more holistic perspective that recognizes the importance of the four components but is more flexible about the starting point of the process. In particular, the SET perspective is more likely to view “information flows from receivers to sender” rather than “sender chooses a message to send” as the starting point. Thus, the SET view emphasizes that any new message must be understood in light of previous communication. Any message a sender communicates is informed by previous messages that have been sent and received. This makes it difficult to think of reducing communication to a simple four-step process that starts with the receiver choosing a message.

The implications of these two fundamental differences will become clearer in our discussion of the four components of the communication process.

17.2. Identify the Message to Be Transmitted

The classic communication process begins when a manager has a message—that is, a specific idea or general information—that they want to communicate to others. It may be a task-, relationship-, or change-oriented message. It can be about a new strategic vision, or simply a story about what happened over the weekend. FBL and TBL managers typically focus on messages that they think will help the organization improve its profitability and efficiency; SET managers will have an additional interest in messages that optimize social and ecological well-being.

Managers (and others) must be selective in the messages they communicate, since time is a limited resource for both them and the target(s) of their communication. Put differently, managers must decide whether particular information is worth communicating to others.[6] The messages they choose will be influenced by their approach to management and their communication styles, which includes the level of filtering. Filtering occurs when information is intentionally withheld or not communicated to others. Filtering can have both positive and negative outcomes. Filtering is positive if managers withhold information that is not relevant to the other person. For example, a manager is filtering when they do not tell their boss what brand of coffee spilled on their ruined laptop computer. Filtering is negative if managers withhold information that could help the organization. For example, the manager whose computer was ruined by coffee is withholding information if they fail to mention that they spilled the coffee on purpose, hoping to get a new and improved computer like their colleague’s.

Managers’ messages may range from one extreme of having too little filtering (the “spray and pray” approach) to the other extreme of having too much filtering (the “withhold and uphold” approach), or any of four additional variations that fall somewhere in-between:[7]

- Spray and pray: In this approach, managers shower members with a lot of data and hope that the members will be able to sort out any information that is relevant for them (see Chapter 18 and the relationship between information systems and data). This can overwhelm others and is particularly inadvisable when members lack the ability to identify which parts of the message are valuable to them.[8]

- Trust and adjust: Rather than give unfiltered information (spray and pray), managers communicating with a trust and adjust approach provide stakeholders all the relevant information they require to identify key issues that need to be addressed. For example, in the opening case Montclair provided her management team with guest speakers and other resources to understand how a more participatively managed airport might operate, and then trusted the team members to discuss and learn how to adapt that knowledge for their situation.[9] Stakeholders trust managers to keep them informed, and managers trust stakeholders to use the information in good faith. Messages encourage everyone to express their view and to learn from others, thereby creating a flexible community where people are constantly adjusting to one another. These managers are more likely to see the information flow from receivers to sender as the first, instead of the final, stage in the communication process. This is the preferred approach among SET managers.

- Tell and sell: Rather than provide all the relevant information (trust and adjust), managers using a tell and sell approach identify and describe the key issues they think need to be addressed, and then seek to convince others to accept their preferred solution, often through elaborate and well-developed presentations. Managers who use a tell and sell approach generally do not solicit feedback and input from others to develop solutions, but only to seek to ensure that others have understood the their instructions (for these managers, the information flow from receivers to sender is the final stage of the communication process, not a formative stage).[10] FBL managers traditionally consider this one-way telling-and-selling to be the most efficient and effective way to communicate.[11] As one manager put it: “That’s what management is: it’s moving other people, getting them to think your idea was theirs.”[12]

- Underscore and explore: As in tell and sell, in this approach managers identify and describe what they think are the key issues that need to be addressed, but unlike with the tell and sell approach, managers don’t provide information about what they think the solution should be. Rather, managers who underscore and explore explicitly listen to feedback from other members so that they can develop better solutions. This communication style has been recommended by scholars,[13] and is the preferred approach among TBL managers who welcome input and participation from others, saying things like “I look to others to see what works and what doesn’t.”[14] Underscore and explore is also becoming increasingly accepted among FBL managers, especially those who work in a dynamic environment.[15]

- Identify and reply: Here managers develop messages based on concerns and issues that followers identify, and reply to those issues. In short, employees set the agenda and managers respond to rumors, innuendos, and information leaks. As a result, messages tend to focus on day-to-day operational concerns, and followers lack the information to understand the long-term strategic issues facing their organization. This is consistent with passive management-by-exception leadership behavior, a variation of avoidance leadership (described in Chapter 15).

- Withhold and uphold: Compared to the other approaches, in this approach managers provide the least amount of information to others. Managers believe that they have all the answers and that others do not need to or are not able to understand the big picture. Even when responding to requests for information or to rumors, managers often simply repeat the “party line” messages that they had sent earlier.

17.2.1. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Identifying the Message

The three approaches to management can be seen to vary along three dimensions related to identifying the message: content, perspective, and directionality. First, as has been mentioned, in terms of content, the FBL and TBL approaches generally prioritize task-oriented messages designed to enhance financial well-being, whereas the SET approach includes a broader range of messages that enhance a variety of forms of well-being. The FBL and TBL approaches emphasize messages that improve organizational productivity and competitiveness, whereas the SET approach adds messages that deliberately try to create positive ecological externalities and build relationships and community.[16]

For example, SET leaders choose messages that foster an ethic of care.[17] This includes deliberately identifying and telling stories of “sparkling moments,” where team members have been particularly good at working together and looking out for each other. These messages draw attention to members’ strengths and to specific instances where they brought out the best in each other. A SET approach engages in dialogue and seeks opportunities to listen to help meet members’ needs, recognizing that people’s private struggles often are grounded in a broader social context, and tells optimistic stories about a future characterized by mutual support that welcomes diversity and embodies collective ethics.[18] In the following quote, a manager who had been trained in an FBL approach shares how they deliberately expanded the messages they sent, so that instead of only communicating task-oriented concerns, they began to show concern for building relationships and community:

I knew that I needed to become more interested in people. I remember, early on in our business, when I had arrogantly said to someone: “Well, our employees, they are people who come in and get the job done and then go home, and that’s it.” And even though [initially] I personally wasn’t very interested in the people, I committed myself to try, every day, to say “hi” and set aside a few minutes with each person. Even if I didn’t feel like it, I could force myself to do it. It was like on my “to do” list. And first thing in the morning I would go to so-and-so, who was a morning person, and say: “So, how is it going? What did you do last night?” And just talk with them. “Okay great, thanks.” And then I’d move on, and through the day I would see everybody in that way. And after a while it changed from something that I had to do, to something that I was actually interested in.[19]

Second, concerning perspective, all three management approaches recognize that the organization is controlled by the people whose messages set the agenda.[20] An FBL approach assumes managers should determine what sorts of messages are sent in the organization: the messages should seek to maximize profits. A TBL approach offers a bit more voice to other stakeholders who can show how a firm can reduce negative socio-ecological externalities to optimize its financial well-being. A SET approach is even more inclined to invite multiple stakeholders to help set the organizational agenda for how best to enhance socio-ecological well-being while maintaining adequate financial well-being. This is consistent with the practices of deliberative dialogue. Deliberative dialogue gathers a variety of stakeholders together to learn ideas from one another about how to address an issue. Deliberative dialogue seeks to foster messages that promote collaboration and listening to find meaning and agreement. The messages are more concerned with showing concern for stakeholders and weighing alternatives than with defending the rightness of one’s own views.[21] As a result, the process helps to set an organization’s agenda that reflects the collective insights of its stakeholders.

Third, with regard to directionality, although the underscore and explore approach favored by TBL managers (and increasingly by FBL managers) invites some two-way communication with stakeholders, it retains an emphasis on the manager’s role in identifying key issues, persuading others, enabling meaning, and initiating change.[22] In contrast, as will be discussed more fully in the “information flow from receivers to sender” component of the communication process, SET managers prefer the trust and adjust perspective, understanding that if you develop a singular message where you “think you have it,” you sacrifice the deeper understanding that comes from incorporating aspects of the truth held by others.[23] A SET approach also promises to increase the frequency of messages that promote justice in the workplace, ensuring that all stakeholders associated with a product or service receive their due and are treated fairly, being especially sensitive to the marginalized (see Chapter 1). James Despain, former manager of Caterpillar Inc.’s Track-Type Tractors 3,000-member division, describes his transition to the trust and adjust approach:

The road to change for me began with the value of Trust. My epiphany was the realization that for my entire life I had trusted no one. I had been taught not to—not purposely, but in subtle ways. Over many years, I was encouraged to write things down for the purpose of “proving” my innocence later if conflict or failure should occur. I had learned to not discuss certain things with certain people, to “spin” information to make things seem better, and to never fully admit being responsible for mistakes or failure. And I was a very good student. After struggling most of one night with what I should do, I decided to trust everyone—everyone. [If I had information I thought others might find relevant] I decided to share what I knew without thinking of any particular motive for sharing. If I were going to get hurt from this, then hurt I would get. This decision at this moment liberated me! From then on, I saw people differently. I began to care for them and was willing to listen to them without judgment. Later I would see how feelings of trust would permeate our organization and would witness the power of it.[24]

Test Your Knowledge

17.3. Encode and Transmit the Message

After determining what message they want to communicate, managers must determine how to encode and communicate that message. Encoding refers to choosing the symbols and media that are used to develop and transmit a message. Messages are typically encoded using words, whether written or spoken, but messages are also sent using nonverbal communication and by things that are left unsaid.[25] When encoding, managers must (a) identify communication barriers to overcome; and (b) choose the medium and channel that will be used to transmit the message. A communication medium refers to the means used to deliver and receive information. Examples of different media include face-to-face conversations, telephone calls, and emails. A communication channel is the organizational path that information travels via a medium. Channels can be formal (upward or downward on the organization’s chain of command) or informal (lateral or diagonal across the chain of command).

When it comes to encoding and fine-tuning messages, managers are increasingly using generative artificial intelligence (AI) software like ChatGPT. Managers use generative AI to help with drafting and revising messages and reports, including as a tool to help do research and generate ideas. Frequent users of AI suggest that with the potential to automate drafting and revising this tool offers, business students need to increase their interpersonal and oral communication skills, as well as listening skills and teamwork. Integrity will become even more important, as well as ability to develop a strategic vision.[26]

17.3.1. Identify and address communication barriers

When choosing how to encode a message, managers must be aware of potential barriers, sometimes called noise. Noise is anything that interferes with the transmission of a message.[27] Noise can impede communication at all four steps of the communication process. Sometimes noise can be literal, such as when workers are trying to talk over the noise of machinery, or when there is a poor phone connection. At other times, noise is more figurative, such as when a manager sends an email to someone who is already overwhelmed with emails. Noise may also occur when there are personality differences or ongoing conflicts between the sender and receiver, or when there is a history of distrust among members. Some barriers to communication are related to organizational factors (e.g., time pressures, communicating across departments or within a team to people with different functional backgrounds), while others are related to individual factors (e.g., language and cultural differences, personality and background differences that contribute to differing perceptions).

Time pressures are a general barrier to communication, including the time needed to craft and encode a message, and the time it takes for a receiver to decode it. Managers often underestimate how long it takes to fully communicate a message that involves major organizational change; this can often take a year or more.[28] We saw evidence of this in the opening case, where Montclair invested a lot of time and resources into communicating the change at the airport. It can be hard work to take complex ideas and present them as succinct messages, as noted in a long letter by Blaise Pascal in 1657: “I have made this longer than usual because I had not had the time to make it shorter.”[29] Just as an organization’s mission and vision statements should be short and punchy, so also should managers describe plans for change in the fewest words possible.[30]

Ambiguous words and symbols can also be a barrier to communication, such as when the body language of a person does not fit the words they are speaking (e.g., if a manager is smiling when they announce the number of people to be laid off). These problems are magnified when communicating across cultures, where similar gestures or actions may be interpreted very differently. For example, in many countries a “thumbs up” gesture means a job well done, but in other places it can mean something rude.[31]

Even people who speak the same language may have difficulty understanding one another. Semantic problems arise when words have different meanings for different people. Part of this may be related to the cohort group one belongs to. For example, for older people the word “sick” means “not healthy,” but for younger people, the word “sick” may mean “good” (as in, “this textbook is really sick”). Similarly, jargon and technical language that is relevant in one profession may not be relevant in another. For example, after reading this book you will be able to have an intelligent conversation with your classmates about the differences between FBL, TBL, and SET managers, but it may not be reasonable to expect people at your workplace to know what you mean by these terms when you refer to your boss’s management style. How often have you intended to send one message, only to be misperceived by a receiver?

The challenge for managers is to anticipate which barriers to communication need to be overcome and then encode their message accordingly. This involves conveying messages using language and symbols that are easy to understand, clear, and unambiguous.[32] For example, chapters in this textbook have been written, revised, and edited many times before the book was published. As authors we have tried to be sensitive to the fact that readers come from a variety of backgrounds and countries, and that many readers may not speak English as their first language. Even so, you may find minor typographical errors and ambiguous sentences. These shortcomings can be overcome, in part, if you have helpful professors and peers to help you understand and learn the material in the book. Indeed, the context in which the book is read will influence the message readers get from it.

This brings us to the observation that, in addition to expressing the message clearly, an important part of encoding involves choosing the best communication medium and channel.

17.3.2. Choose communication media and channels

Communication media

Marshall McLuhan famously observed, “The medium is the message.”[33] McLuhan’s observation points out that a message cannot be separated from the medium that transmits it. For example, the message of “I love you” means something different if you hear it from your mother, your sibling, a romantic partner, or a three-year-old nephew. In a workplace setting, an employee who has achieved something noteworthy should be recognized, but it may mean different things if the CEO sends an email with congratulations, personally presents the employee with a plaque at a departmental meeting, or features the employee on the company’s web page.

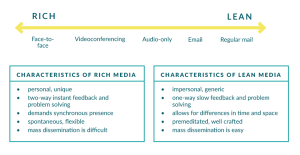

An important consideration in choosing a communication medium is media richness.[34] Media richness refers to a medium’s ability to resolve ambiguity. Media richness is determined by the speed and accuracy of feedback that is possible, the verbal and nonverbal cues that are employed, and the level of language used.[35] As shown in Figure 17.2, face-to-face communication is the richest medium because it allows participants to not only hear the content of each other’s messages and their tone of voice but to also see subtle body language. It also allows for immediate feedback and the personalizing of messages. Face-to-face communication can take place one-on-one (preferred by 85 percent of frontline supervisors[36]) or within a group. Face-to-face communication has a positive effect on employee satisfaction.[37] Research suggests that in some cases the actual words spoken in a face-to-face exchange may account for less than 20 percent of the total information that is communicated. As much as another 30 percent may be accounted for by the vocal characteristics of the message, and about 50 percent by the accompanying facial and body language.[38] Videoconferencing is a less rich medium than face-to-face, and audio-only communication is less rich than videoconferencing (but richer than non-audio media).

Figure 17.2. Communication media along the rich vs. lean continuum

Email and other forms of written communication are less rich than video or audio, but it is possible for authors to add visual and emotional content to the written communication via emoticons or emojis. Research suggests that communication via email is more effective when used by organizational members who have previously established a strong working relationship with one another.[39] Emails are particularly useful when managers need to transmit a lot of detailed information, especially if it is information that the receiver will need to reference in the future. Because emails are faster and amenable to attaching large document files, they are richer than regular mail.

Overall, the volume of information that is being communicated in the workplace has increased by at least fifteen times over pre-internet days, but there has been a decrease in richness and personalized correspondence.[40] This has contributed to information overload. As one manager overwhelmed by email put it: “Previously I did not know what I was missing, and I was really happy in that ignorance. Now I get information, and I think ‘I really should read this,’ and I can’t, I really don’t have the time, and I feel really inadequate.”[41] Impersonal formal written documents, including unaddressed bulletins or mass emails, are very lean communication media because they do not build on known interpersonal relationships and understandings.

Different managers will have different skill and comfort levels in different media. Some will be great at face-to-face meetings, others at writing compelling reports, and so on. Similarly, recipients will prefer some media over others (some prefer emails, others face-to-face meetings). Communication works best when there is a match between the preferred media of the manager and members. Often it is a good idea for a message to be sent via various media, and carried by various channels, to appeal to more recipients.

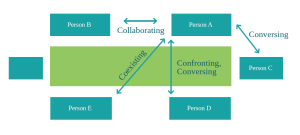

Perhaps the most pervasive yet least acknowledged communication medium is evident in the messages symbolically embedded in organizational processes, culture, structures, and systems (see Chapter 11). For example, the physical layout or proxemics (i.e., the use of interpersonal space to convey a message) in an organization represents an important form of nonverbal communication.[42] Figure 17.3 shows how seating arrangements around a table can influence the nature of the communication that takes place between participants. Sitting next to a person signals collaboration, sitting at a corner with someone is associated with conversation, sitting directly across from someone can be perceived as either conversational or confrontational, and sitting diagonally across a table is the preferred position if two people need to share the same space but do not wish to interact.[43]

Figure 17.3. Effects of seating on communication

Communication channels

Along with choosing appropriate communication medium, managers must also select the appropriate channel, or the path that a message travels. In addition to messages sent to members within the same team or department, researchers have identified two basic types of channels: formal (upward and downward), and informal (lateral and diagonal).

An organization’s formal communication channels follow the lines of authority that are shown on an organization chart (Chapter 11). Formal downward channels are used when messages are sent from bosses to subordinates along the chain of command, such as when managers provide instructions or information to employees. This is the most studied channel. Unfortunately, a message can lose as much as 25 percent of its intended meaning each time it moves one hierarchical level down the chain of command.[44] This might help to explain why employees would much prefer receiving information from their immediate supervisor rather than from senior managers—they feel more confident that they will understand what the message is intended to mean.[45] More meaning is retained (a) the lower the number of hierarchical levels a message travels; (b) the lower the status and power differences between levels; (c) the greater the level of trust among organizational members at different levels; and (d) the greater the subordinates’ desire for upward mobility.[46] Formal upward channels are used when messages are sent up the chain of command, such as when subordinates provide feedback to managers, confirm that tasks have been completed, convey financial information, or seek to influence managerial decision-making. As will be discussed more fully in the fourth component of the communication process (information flow from receivers to sender), many employees complain that their manager is not receptive to their feedback.

An organization’s informal communication channels exist outside of the formal chain of command. An informal lateral channel is being used when, for example, a member of the accounting department directly contacts a member of the sales department (who is at the same hierarchical level but in a different department) in order to clarify a sales invoice (this is quicker and potentially more accurate than going through the formal chain of command, which would involve the heads of the two departments). An informal diagonal channel is being used when a member of the accounting department directly contacts the head of the sales department (who is at a higher hierarchical level but in a different department) to clarify a sales invoice (this is also quicker and likely more accurate than going through the formal chain of command, which would involve the heads of the two departments). One study found that communication worked especially well in organizations where members were divided into smaller groups or teams of ten to fifteen members (to facilitate face-to-face interaction), and each of the groups was in turn connected to each other via informal go-between members (these “social butterflies” were not formally assigned to act as go-betweens, rather they were an important part of the organization’s grapevine).[47]

A grapevine is an informal diagonal and lateral communication channel that can carry both organizational information (e.g., rumors about an impending merger) and personal information (e.g., who gets along with whom). The grapevine helps employees meet their needs for social interaction, and it is a fast and efficient channel of communication that provides a valuable window into what is important to organizational members.[48] Sometimes the grapevine transmits inaccurate information, but generally it is about 80 percent accurate.[49] Managers should assume that the grapevine will be active and not try to suppress it, but they should be quick to correct misinformation.

17.3.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Encoding

FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to encoding parallel one another, but with two important differences. First, there will be different understandings of noise and barriers to communication. For example, whereas a SET approach values information about socio-ecological externalities associated with a firm’s product or service, from an FBL perspective that same information may be treated as unnecessary noise that distracts members from the core purpose of the firm. Similarly, an FBL approach may emphasize the importance of similarities among team members to facilitate communication, whereas from a SET perspective differences among members provide an opportunity for a richer understanding of issues.

Second, although FBL, TBL, and SET managers may use the exact same media or channels to communicate messages, they often do so with different intentions and outcomes. For example, productivity-oriented FBL managers generally choose leaner media that allow them to communicate with many people at once (e.g., a report sent by email) because they deem this to be the most efficient use of their time.[50] In contrast, even though SET managers generally prefer richer media, they may choose to send a report by email for socio-ecological reasons (e.g., because it reduces greenhouse gas emissions that would arise from traveling to different sites to communicate face-to-face). Research suggests that when new communication media are introduced in an organization, they reinforce existing communication and power structures, which suggests that their use in FBL firms will contribute to a greater emphasis on financial well-being, whereas their use in SET firms will contribute to a greater emphasis on socio-ecological well-being.[51]

That said, there may be features embedded within different media that make them more attractive to and more prone to support one management approach over another. For example, on the one hand social media is touted for its ability to enhance financial well-being at a low cost (consistent with an FBL approach). On the other hand, the transparency and opportunities for multi-stakeholder collaboration and engagement offered by social media are very appealing to SET managers. Perhaps social media will be equally beneficial to all organizations. However, it also has potential negatives: it has been noted that social media can have unprecedented, far-reaching implications for both managers and employees in terms of monitoring and surveillance, and it may enable new forms of bullying in the workplace.[52]

Test Your Knowledge

17.4. Receive and Decode the Message

In this step, the receiver attributes meaning to the message through a process called decoding. The decoding process mirrors the encoding process, and thus has two components. First, the communication medium and the channel chosen can affect the richness and meaning of a message. For example, a face-to-face “thank you for a job well done” from a CEO is decoded differently than being named on a list of employees in a company newsletter.

Second, as with the encoding process, the decoding process works best when receivers are aware of potential noise and barriers to communication that may impede their understanding of the message. Unfortunately, people often fail to consider such barriers. Everyone decodes (and encodes) messages through the lens of their own unique needs, experiences, values, culture, abilities, shortcomings, aspirations, goals, and attitudes. The greater the mismatch between sender and receiver, the greater the likelihood that the meaning of the message will differ between them.[53] For example, if a receiver does not trust a sender, the receiver will tend to interpret the message with skepticism.

Researchers have identified two kinds of perception biases that can act as barriers to understanding when decoding a message. The first kind of perception problem is related to stereotyping—making assumptions about other people based solely on their gender, race, age, or some other characteristic. Stereotyping distorts reality by suggesting that all people in a particular category share the same characteristics, which simply is not true. Communication is hampered when people apply unhelpful or inaccurate stereotypes. For example, communication can come to a standstill if a union leader perceives managers to be concerned only about making more money and not caring about the welfare of workers, or if managers perceive union members as being lazy and not caring about a firm’s profitability.

Consider your views about business and management. How would you describe a typical business, or a typical manager? Where did your views come from, how were they shaped, and how accurate are they? Of course, it is in the interest of businesses for people to have positive views about business and look up to managers. Perhaps this helps to explain why managers have traditionally been expected to dress professionally and are paid well. Businesses are also interested in promoting positive views in the media. For example, at one time Procter & Gamble created the following rules for where it would place its television advertisements: “There will be no material on any of our programs which could in any way further the concept of business as cold, ruthless, and lacking all sentiment and spiritual motivation.” If managers were to be cast in the role of villains, “it must be made clear” that this was not typical and was despised by other managers as much as by society in general.[54]

A second kind of perception problem is related to selective perception, which occurs when people (often unintentionally) screen out or filter information. This is evident, for example, when people “tune out” ads on television or the internet. Selective perception helps us to focus on our areas of expertise and to avoid distractions, but it is a problem when we tune out things that are important. Remember Dennis Gioa (opening case in Chapter 7)? He was so intent on following scripts that would help him get promoted within the Ford Motor Company that he lost sight of the burn deaths his decisions were contributing to. People often tune out bad news or negative feedback. Managers therefore need to be creative in finding ways to listen to and to convey such messages so that selective perception does not occur. For example, if a manager thinks that people are tuning out information that appears in the weekly newsletter, then they may want to use a different medium (e.g., personalized email or face-to-face meetings) to ensure that messages don’t get overlooked.

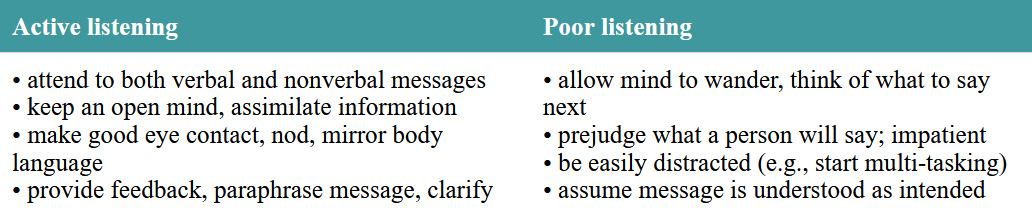

The most important decoding skill is being a good listener, which includes but goes beyond not falling prey to perception biases. Good listening means being attuned to the words being communicated as well as to any other signals (tone, body language, word choice, what is not being said, etc.). Being a good listener is difficult—talking is easier. We often confuse “hearing” a message with “receiving” a message. Good listeners can focus on and absorb what another person is trying to communicate.[55] Table 17.1 describes the hallmarks of active (good) and poor listeners. Listening well is related to well-being and quality of relationships, and also to job knowledge, job performance, job attitudes, and leadership.[56]

Table 17.1. Hallmarks of active and poor listening

Given the traditional assumptions about the importance of one-way manager-to-subordinate communication, it should not come as a surprise that most studies focus on how subordinates listen to managers, and very little research looks at how managers listen to their employees.[57] This is unfortunate because it is important for managers to be good listeners. Listening improves communication and promises to improve the quality of decision-making in organizations (see the discussion of feedback below). Listening provides an inexpensive positive reinforcement for other members and helps to create general positive feelings that can increase their support for a manager.[58] But these benefits don’t appear if managers fail to show that they are listening.

Finally, it is important to note that decoding happens at both the individual and collective levels in all organizations. While decoding is traditionally discussed at the individual level of analysis (how an individual receiver decodes a message), decoding also commonly takes place at a collective level of analysis (how a group of receivers decode a message). Consider what happened when Larry Mauws, then CEO of Westward Industries (see Chapter 18), announced to his employees that they were going to completely redesign their main product, a three-wheeled car used by parking patrol officers throughout the United States. This simple message triggered a time of collective decoding. At a basic level, everyone in the organization understood the message: they needed to redesign the car to have specific additional features. But the implications of this message required a deeper level of decoding that took months of work, because manufacturing the redesigned product required members not only to make changes in their individual tasks but also to understand changes in how their co-workers performed their specific tasks. At this deeper level, the implications of the message could not have been fully decoded by any one person, including Mauws himself. Rather, to understand the meaning of manufacturing the redesigned car required members to relearn their own tasks in the context of their interrelationships with the work of the people around them.[59] The notion of collective decoding enables members to develop a shared understanding of their combined work and how their individual tasks contribute to it. Collective decoding is related to organizational change and learning (see Chapter 13).

17.4.1. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Decoding

There are many similarities among FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to decoding, but also two differences. First, as is evident throughout this book, the three approaches to management have different selective perception biases. FBL decoding focuses on task-related issues like productivity and efficiency, TBL adds a focus on socio-ecological externalities that may help a firm to enhance profits, and SET is receptive to messages that optimize socio-ecological well-being that goes beyond profit maximization.

Second, because of their grounding in individualism, FBL and TBL perspectives are more likely emphasize individual decoding as compared to the SET approach, which is more likely to emphasize collective decoding on account of its tendency to embrace multiple forms of well-being and to encourage diverse voices. The SET approach emphasizes the merit in decoding a message in community, so that it is understood and shared more broadly. The SET approach to decoding is thus oriented toward achieving mutual understanding (how is a message understood collectively), which is more than simply the linear transfer of knowledge from one person to the next.[60] Collective decoding recognizes and respects the unique knowledge that each member brings to the organization, and thereby provides the opportunity for creating new meanings that are richer than either the sender or an individual receiver could come up with on their own.[61] This will be discussed further in the next section.

Test Your Knowledge

17.5. Information Flow from Receivers to Sender

From an FBL or TBL perspective, the information flow from receivers to sender is seen as the final step in the communication process (feedback), and the focus is on determining whether the sender’s message was received as intended. But from a SET perspective, the information flow from receivers to sender is seen as the first step in the communication process (feedforward), and the focus is on whether the senders are attuned to intended receivers, which in turn helps senders to develop their messages. Of course, both views can be true at the same time and both operate among all managers, but which view is emphasized will have an effect on communication practices and content. We will examine each of these views.

17.5.1. Feedback regarding whether a message was successfully received

The receiver-to-sender information flow has traditionally focused on how the receiver lets the sender know whether the message has been received and interpreted as intended. Feedback can be as simple as hitting reply and saying, “I received your message and will comply.” Or maybe, “I received your message but don’t understand it, please clarify.” Or, “I have received your message and have some follow-up questions for clarification, and perhaps a suggestion you might want to consider.” Sometimes feedback is evident in the nonverbal communication of a receiver. A puzzled look, for example, implies that additional information is needed. Face-to-face communication is excellent for providing immediate feedback, and facilitates the opportunity for paraphrasing messages and asking questions of clarification. In this sense feedback is like active listening, where the receiver paraphrases the message and provides nonverbal cues of attention. Other times feedback is much more complicated, especially when the receiver does not fully understand what the message means or how to respond to it. In such cases, it is often helpful to choose a richer medium to provide feedback rather than the medium that was used to transmit the original message. For example, if an organizational member is unclear about how to interpret an email written by a colleague, the member would be well-advised to talk with the colleague face-to-face or over the phone.

Feedback has two key benefits. First, it can confirm that the original message was received and interpreted as intended, and thereby complete the four-part communication process. Of course, sometimes recipients may think they understand a message, but their understanding differs from the message that was intended by the sender. For example, there may be a difference between what a parent and what a child think it means to have a clean room. Noncompliance with a request is another signal that the original message has not been understood.

Second, feedback provides an opportunity for the original sender to learn something new that will enable them to improve subsequent messages (this is elaborated on in the following section on feedforward communication).[62] Perhaps the most important aspect of feedback is the opportunity for managers to learn from constructive criticism of their original message. However, many managers are not very receptive to constructive criticism from their subordinates.[63] One study found that when ranking forty-nine items of managerial effectiveness, subordinates rated their manager’s receptivity to upward feedback at the bottom. Indeed, receptivity to upward feedback was identified as a strength for only 16 percent of managers.[64]

When managers are unable or unwilling to learn from the feedback they receive from others, they are prone to repeating ineffective messages and holding unrealistic ideas about their organization. Indeed, senior managers of failing organizations often have a much rosier view of their organization than do outsiders, and senior managers often see fewer organizational problems than their junior colleagues.[65] In such cases, the communication process becomes like an echo chamber, with managers limiting the kind of information they send and receive (i.e., regarding what they pay attention to versus what they dismiss as noise). To prevent echo chambers, managers can use a variety of techniques to nurture feedforward communication. As will be describe more fully in the next section, these techniques include deliberately inviting ideas from others and listening to them, acknowledging and thanking team members who challenge the status quo, and seeking to build on the positive aspects of others’ ideas rather than demonstrate their shortcomings.[66]

Research suggests that managers who seek genuine feedback tend to be perceived as more interested in nurturing community, in developing positive working relationships, and in demonstrating consideration and concern for others. They are also perceived to be more friendly, approachable, and empathetic. Such managers tend to value differences and to work well with people who have different points of view, find ways to enhance multiple views, are open to new ideas and ways of doing things, and have excellent listening skills (including avoiding criticizing others before giving them a fair hearing, and listening to perspectives that are different than their own). Such managers are also known for giving honest and direct feedback.[67]

17.5.2. Feedforward communication that informs subsequent messaging

A feedforward understanding of receiver-to-sender information flow emphasizes how, before a sender chooses and encodes a message, they first consider previous communication with the intended receiver(s) of their message. While all managers do this to some extent, those operating within a SET perspective think about it more deliberately. For example, recall (from Chapter 13) that prior to talking to supervisors about the need to hire more women and promote more minorities, AT&T corporate vice president Robert Greenleaf deliberately reminded himself and the supervisors of their previous interactions, shared experiences, and accomplishments. Greenleaf also reminded himself that he was part of the problem, part of the ongoing communication and work practices that had caused women to be underrepresented in the workforce and minorities to be underrepresented in various positions at AT&T.[68]

At a more philosophical level, an emphasis on feedforward communication can be seen as having four key elements. First, this approach recognizes that an organization exists only because of prior communications of members, and this prior communication provides the basis for any subsequent communication.[69] This is illustrated by Greenleaf’s example, even though he may not have been thinking in these abstract terms. From a feedforward perspective, organizations are a communicative accomplishment, where organizational realities are socially constructed by stakeholders through communicating.[70]

Second, in its ideal form, a SET approach to feedforward communication does not privilege managers over other members and stakeholders. It recognizes that without followers there are no leaders, and without customers and suppliers there are no organizations. Feedforward communication sensitizes managers to the views and needs of the larger organization and community, just as it sensitizes followers and others to the views and needs of managers. In the Greenleaf example, he de-emphasized his authority and status, and instead deliberately assumed a servant leadership role where he listened to and supported the ideas of supervisors who were much further down the hierarchy. Moreover, he attended to the (unspoken) messages sent by the marginalized (in this case, underrepresented women and minorities).

Third, a SET approach to feedforward communication recognizes that communication is a basic life process, much more than simply an exchange of information or a tool used by managers to achieve particular goals.[71] Yes, organizational communication is about achieving organizational goals, but it goes beyond that. It also relates to meaningful work and relationships with co-workers and other stakeholders. And the parameters of feedforward communication go beyond the organization itself, extending to people’s home life, past generations and hopes for future generations, and the messages we get from and send to the natural world.

Finally, and perhaps of more practical relevance, feedforward communication draws attention to the idea that the transmission of specific messages takes place in the context of, and contributes to, a larger organizational story. A challenge for managers is to understand that larger story and to send messages that will be compelling and inspirational for others participating in the story. This is a particular challenge facing entrepreneurs, which we will look at in the section about entrepreneurial storytelling toward the end of the chapter.

17.5.3. FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to feedback/forward

While all three management approaches recognize the importance of feedback and feedforward communication from receivers-to-senders, their emphases are different. FBL and TBL approaches tend to see receiver-to-sender information flow as the final step in the communication process, emphasizing that this step is about feedback. While managers are fine at receiving feedback at a basic level (i.e., to determine whether their message was received as intended), research suggests that managers are generally perceived to be poor at receiving constructive feedback from subordinates (e.g., how can they improve their messages going forward). Managers who are good at receiving constructive feedback often share some behaviors that are emphasized in SET management (e.g., being interested in nurturing community, seeking to enhance multiple views, being open to new ideas and ways of doing things).[72] In general, the SET management approach is more likely than FBL and TBL approaches to see the receiver-to-sender information flow as the starting point of the communication process.

Test Your Knowledge

17.6. Entrepreneurial Storytelling

The question of whether communication starts with a sender choosing a message to send or starts with information flowing from intended receivers of the message lies at the crux of understanding the communication challenges facing entrepreneurs. On the one hand, entrepreneurs need to be experts in listening to the information coming from the key stakeholders for whom the start-up is trying to create value. The better entrepreneurs are at this, the more attuned their new ventures will be to the market. On the other hand, entrepreneurs need to be masterful at developing and transmitting their organizational message. In particular, the better entrepreneurs are at telling the story of what their new venture represents, the more likely they will be to inspire the participation of key stakeholders (employees, suppliers, and customers). Establishing the basic story of the start-up provides the context for subsequent communication within and about it.[73]

In general, regardless of management style or entrepreneurial stage, it is essential for all entrepreneurs to be able to communicate their ideas to others, and to get other people excited about their ideas.[74] Their communications need to inspire people. Research reveals factors that can help the entrepreneur to be more inspiring.[75] The most important factors in inspirational communication are behavioral; the words and structure and tone determine how inspirational a communication will be. The most inspirational communications make use of symbolic language, concrete images, and value-based positions. And what’s the best way to do all these things? Tell stories.

We have evolved to make sense of the world in terms of stories.[76] If you have ever had the experience of not knowing where to start, of feeling as though you need to say several things at the same time to express your meaning, then you have encountered a significant problem with language: it is serial in nature. That is, you can only say one word at a time, and to make sense, those words must come in a sequential order. In contrast to the serial nature of language, our brains are connectionist: we can hold several thoughts at the same time and any particular thought can simultaneously produce many reactions in our brains. When someone says “dog,” your mind may immediately picture your family pet, famous dogs from pop culture, memories of high humidity summer days (“the dog days of summer”), or any number of other related ideas—plus all the emotions that attach to each idea.

Traditional language cannot easily express the complexity of our thinking, which is why poetry breaks the rules of writing and why we often say that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” But the most powerful way to communicate complex ideas, especially for entrepreneurs, is through stories. The Homo sapiens (modern human) species has been identified through African fossils as more than 200,000 years old. In contrast, the oldest known writing is only 10,000 years old, and writing probably wasn’t consistently practiced until thousands of years after that. This means that humanity has spent more than 95 percent of its history without writing. During that time knowledge was shared in the form of stories, and it still is now. Think about the fairy tales and other lessons you learned as a child even before you could read. Think of the parts of class lectures that are most interesting and memorable. Our brains have evolved to make sense of the world through stories, and we have been trained to do so since birth.

As a result, stories are how we think. We remember information better when we hear it in the form of a story.[77] We pay more attention, we find information more interesting, and we notice more details when we hear stories.[78] And because we already have simple generic story plots in our memories as scripts, we require less mental energy to make sense of a story and to see how its parts connect. In fact, stories are so important to our thinking that we sometimes misremember in ways that improve the story rather than reflect the true facts.[79]

Entrepreneurs will be more successful if they can tell compelling stories about their goals and their vision. Stories can help others to see the potential in their ideas for a new venture. For example, initial public offerings (when a firm’s ownership shares are sold for the first time on a public securities exchange) gain more support when the founders are effective storytellers.[80] Entrepreneurial stories can also encourage others to act on behalf of a start-up. Stakeholders are more likely to engage with good stories,[81] and they will usually do better retelling a vivid story than they will developing their own argument to support the entrepreneurial goal.[82] Concrete details, word pictures, and a clear plotline are keys to powerfully communicating an entrepreneurial goal. When investors ask you “What’s your story?” they mean it literally.

A study of storytelling associated with new start-ups on the crowdsourcing site Kickstarter found that there were two types of successful stories: results-in-progress, and ongoing journey.[83] The first type, results-in-progress stories—more likely to be associated with FBL entrepreneurs—tend to focus on materially valuable outcomes, to rely on advanced technology, and to have little concern for the social well-being of the larger community. These stories focus on past accomplishments and future steps, seeking to establish a transactional engagement. A typical results-in-progress story might go like this: “ZZ is a result of YY years/months of . . . We’ve produced/built XX . . . Now we are ready to . . . We need your support in order to . . . .”

Ongoing journey stories—more likely to be used by SET entrepreneurs—tend to have a high social orientation (benefit to people in need), a low emphasis on material outcomes, and a lower need for sophisticated technology. Ongoing journey stories focus on past developments and a vision for the future, seeking to establish emotional engagement with the listener. A typical ongoing journey story might go like this: “XX years ago we realized/started thinking about . . . We hired YY. who noted that . . . We would like this project to be . . . Our project is to promote ZZ . . . We ask you to become part of/join this journey.”

Of particular relevance for this chapter, organizational stories provide the all-important context for the subsequent communication that takes place within and about them.[84] In terms of the communication cycles associated with the four components of the communication process described in this chapter, entrepreneurs draw ideas from stakeholders (feedforward) to develop their message, which they encode as a story in order to inspire stakeholders (decoding), who in turn provide new feedback to improve the message, enhance the story, and create more engaged stakeholder listeners.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Managers spend about 75 percent of their time communicating with others.

- The communication process consists of the following four components:(i) Message is identified

- An FBL approach emphasizes transmitting task-oriented knowledge that will help to enhance an organization’s financial well-being; the focus is on messages managers send to other organizational members; the goal of managers is to convince other members to accept their message.

- A SET approach emphasizes messages that enhance socio-ecological well-being; the focus is on messages all stakeholders send to one another; the goal of managers is to facilitate the exchange of ideas and identification of the best ones.

(ii) Message is encoded and transmitted (through chosen media and channels)

- FBL managers seek to reduce noise that comes from potential barriers and differences among recipients, and to send messages in the most financially cost-effective way.

- SET managers seek to reduce noise but welcome information about socio-ecological externalities (which would be noise from an FBL perspective), and to use the richest communication medium that is practical.

(iii) The message is received and decoded

- An FBL approach focuses on how individuals decode messages and tune out non-instrumental distractions.

- A SET approach focuses on how groups decode messages and tune in matters related to socio-ecological well-being.

(iv) Information flow from receivers to the sender

- An FBL approach prefers feedback communication that confirms that messages are understood as intended by senders.

- A SET approach prefers feedforward communication as the first step in developing subsequent messages.

For each of the four components, a TBL approach is consistent with FBL practices, unless there is a business case supporting the adoption of SET practices.

- Entrepreneurs who provide an organizational story provide context for subsequent communications within and about the start-up.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Identify and briefly describe the four steps in the communication process. What are the key differences between the FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to the communication process? What are the key similarities? Explain.

- Generative AI is spreading through the workplace. What are the pros and cons of this increasing use? What workplace skills do you think will become more important going forward, and which will become less important? Have you ever worked on group projects where some members’ contributions are largely based on generative AI? What effect do you think this had on group dynamics and on the quality of the final report?

- Think of a time when you participated in collective decoding, that is, when your own understanding of a message was enhanced because you were interpreting it during conversations with others. Was the sender of the message part of the process of decoding it? Do you think the message that you understood after this process was more multifaceted and clearer than the sender’s own understanding of the original message?

- Describe the difference between rich and lean media. What criteria should managers use to select a medium for their message? What effect do you think social media has had on the relative power of managers and subordinates in organizations? How about on their mental health? Explain your answer.

- Explain why it might be challenging for FBL managers to accept constructive feedback. Would this be different for TBL or SET managers? Explain.

- Have you ever worked with others whose communication style promoted an ethic of care in the workplace? Did other co-workers follow their example? Based on your experience, what is the proper balance between task-oriented and care-oriented messages in organizations? What are reasons you personally would, and would not, deliberately increase care-oriented communications in an organization.

- Consider the following statement:

“In this era of globalization and intense competition, managers really don’t have any alternative but to communicate in ways consistent with FBL management. If they don’t continually focus on the importance of productivity and profitability in their communications, their subordinates will not get the message, and thus their company’s profitability and productivity will suffer because other companies are relentlessly pursuing these goals. The SET approach to communication sounds good, but it simply will not work.”

Do you agree or disagree with the statement? Explain your reasoning.

- Think about a new venture you might be interested in starting. Which stakeholders should you listen to as you develop your ideas for the new organization? What is the basic story that you would tell others about the new venture? Describe how it would inspire stakeholder engagement, and what context you would want it to provide for subsequent communication within and about your start-up. Is yours an FBL, TBL, or SET story? Explain.

- This case is based on a personal interview with one of the authors (March 27, 2001). Names and other details have been changed for reasons of confidentiality and pedagogy. ↵

- Communication between organizations (e.g., supply chain management) and from organizations to customers (e.g., marketing) are also important but will not be the focus of this chapter. ↵

- Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. Harper and Row. ↵

- Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press. This linear one-way framework, where the source (manager) sends a message to a receiver (follower), who is influenced to behave in the way desired by the source, continues to characterize communication practices in many firms and is used by even the most accomplished scholars at times. Rubin, B. D., & Gigliotti, R. A. (2017). Communication: Sine qua non of organizational leadership theory and practice. International Journal of Business Communication, 54(1): 12–30. ↵

- Rubin & Gigliotti (2017). ↵

- Clampitt, P. G., DeKoch, R. J., & Cashman, T. (2000). A strategy for communicating about uncertainty. Academy of Management Perspectives [was Academy of Management Executive], 14(4): 41–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AME.2000.3979815 ↵

- Note that the trust and adjust approach, preferred by SET management, is not in the original list of five described in Clampitt et al. (2000). ↵

- For example, John Berardino “peppered his testimony before the US Congress with a glut of accounting details to deflect responsibility for Arthur Anderson’s role in the Enron scandal.” Page 12 in Fairhurst, G. T., & Connaughton, S. L. (2014). Leadership: A communicative perspective. Leadership, 10(1): 7–35. ↵

- Nicholson, J., & Kurucz, E. (2019). Relational leadership for sustainability: Building an ethical framework from the moral theory of “ethics of care.” Journal of Business Ethics, 156: 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3593-4 ↵

- Van Quaquebeke, N., & Gerpott, F. H. (2023). Tell-and-sell or ask-and-listen: A self-concept perspective on why it needs leadership communication flexibility to engage subordinates at work. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53: 101666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101666 ↵

- Nicholson & Kurucz (2017). ↵

- Vandenbosch, B., Saatcioglu, A., & Fay, S. (2006). Idea management: A systemic view. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3): 259–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00590.x ↵

- Clampitt et al. (2000). ↵

- Nicholson & Kurucz (2017). ↵

- “Consensus-builders” in Vandenbosch et al. (2006). ↵

- These three differences build on Vandenbosch et al. (2006). ↵

- Nicholson & Kurucz (2017). ↵

- Lawrence, T. B., & Maitlis, S. (2012). Care and possibility: Enacting an ethic of care through narrative practice. Academy of Management Review, 37(4): 641–663. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0466 ↵

- Quote taken from Dyck, B. (2002). A grounded, faith-based moral point of view of management. In T. Rose (Ed.), Proceedings of Organizational Theory Division, 23: (12–23). Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Winnipeg, MB. The names of people drawn from this article have been disguised, but the situations are accurate. ↵

- Putnam, L. L., Phillips, N. & Chapman, P. (1996). Metaphors of communication and organization. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Managing organizations: Current issues (Chapter 7, pp. 125–158). Sage; Dispensa, J. M., & Brulle, R. J. (2003). Media’s social construction of environmental issues: Focus on global warming—a comparative study. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 23(10): 74–105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443330310790327 ↵

- Buchanan, A., & O’Neill, M. (2001). Inclusion and diversity: Finding common ground for organizational action: A deliberative dialogue guide. Canadian Council for International Co-operation; see also Stajkovic, K., & Stajkovic, A. D. (2024). Ethics of care leadership, racial inclusion, and economic health in the cities: Is there a female leadership advantage? Journal of Business Ethics, 189(4): 699–721. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05564-0 ↵

- Nicholson & Kurucz (2017). ↵

- Lederach, J. P. (2004). Interview by J. Portilla. Beyond Intractabilty.org. Retrieved April, 2007, from https://www.beyondintractability.org/audiodisplay/lederach-j; see also Huebner, C. K. (2006). A precarious peace. Herald Press. ↵

- Page 143 in Despain, J. & Converse, J. M. (2003). . . . And dignity for all: Unlocking the greatness of value-based leadership. Prentice-Hall/Financial Times. ↵

- Chitac, I. M., Knowles, D., & Dhaliwal, S. (2024). What is not said in organisational methodology: How to measure non-verbal communication. Management Decision, 62(4): 1216–1237. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2022-0618 ↵

- Cardon, P., Fleischmann, C., Logemann, M., Heidewald, J., Aritz, J., & Swartz, S. (2024). Competencies needed by business professionals in the AI age: Character and communication lead the way. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 87(2): 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294906231208166 ↵

- Definition taken from page 262 in Williams, C., Champion, T., & Hall, I. (2015). MGMT: Principles of management (2nd Canadian ed.). Nelson Education. ↵

- Clampitt et al. (2000). For a study of specific factors that restrain change and the importance of timing, see Abrantes, A. C. M., Bakenhus, M., & Ferreira, A. I. (2024). The support of internal communication during organizational change processes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(5): 1030–1050. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2023-0222 ↵

- Quote Investigator. Quote origin: If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter. (2012, April 12). https://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/04/28/shorter-letter/ ↵

- Larkin, T. J., & Larkin, S. (1996, May–June). Reaching and changing front-line employees. Harvard Business Review, 95–104. ↵

- Cotton, G. (2013, August 13). Gestures to avoid in cross-cultural business: In other words, “Keep your fingers to yourself!” Huffington Post. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/gayle-cotton/cross-cultural-gestures_b_3437653.html ↵

- That said, note that qualities such as these are often mutually opposed—for example, precision and simplicity can be pretty near opposites. ↵

- McLuhan, M. (1994). Understanding media: The extensions of man. MIT Press. ↵

- Kaneko, A. (2023). Team communication in the workplace: Interplay of communication channels and performance. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294906231190584 ↵

- Richness also includes the ability to express language variety. See Daft, R. L., &. Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32(5): 554–571; Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H., & Trevino, L. K. (1987). Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: Implications for information systems. MIS Quarterly, 11: 335–366; Neufeld, D. J., Dyck, B., & Brotheridge, C. M. (2001). An exploratory study of electronic mail as a rich communication medium in a global virtual organization. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2001.927134 ↵

- Larkin & Larkin (1996). ↵