Part 4: Leading

15. Leadership

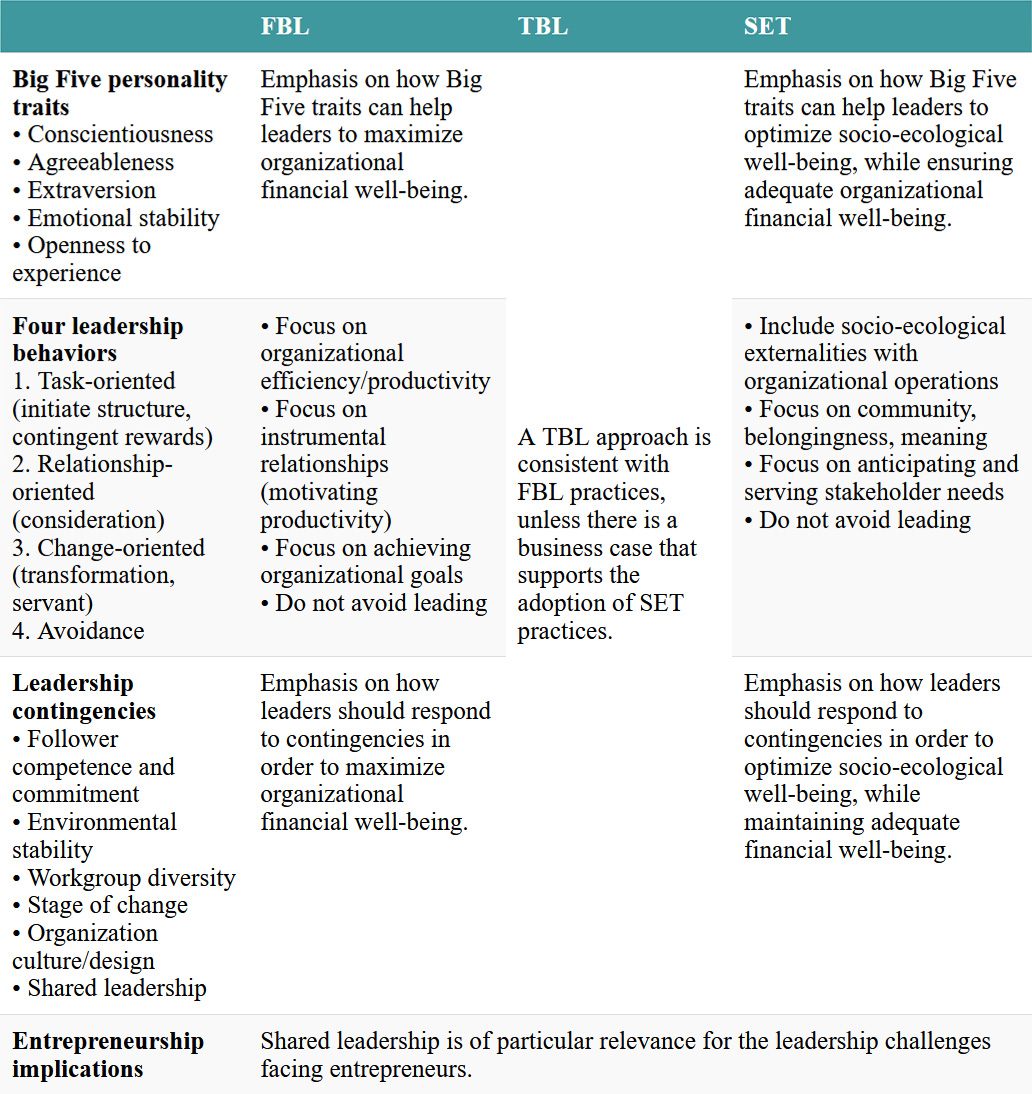

Chapter 15 provides an overview of the personality traits, behaviors, and context associated with leadership, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe how the Big Five personality traits in leaders are related to measures of perceived leader effectiveness, follower satisfaction with leaders, and group performance.

- Describe the four main types of leadership behavior, and how each is related to measures of leader effectiveness, follower satisfaction with leaders, and group performance.

- Describe key contingencies and how they influence which leadership behavior is the most appropriate in a given situation.

- Describe the hallmarks and benefits of shared leadership and explain how it is of particular relevance for entrepreneurs.

15.0. Opening Case: Leadership of Design

CEO Melanie Perkins is the extraordinary leader of Canva, a company known for its deliberately user-friendly graphic design software. According to Forbes: “Melanie Perkins is undoubtedly one of the most inspiring figures in the global technology landscape.”[1] She co-founded Canva in 2013, along with Cliff Obrecht and Cameron Adams, and by 2023 it had revenues of $2 billion and her net worth was estimated to be $3.6 billion.[2] By 2024 Canva had 5,500 employees and 200 million users.

The success of Canva has been shaped greatly by Perkins’s traits and behaviors. Perhaps Perkins’s most important trait is her persistence and her commitment to big dreams, both components of conscientiousness. For example, Perkins never gave up pitching Canva to potential investors, who may have been reluctant to invest for a variety of reasons (e.g., only 2 percent of venture-backed businesses are led by women, and Canva’s location in Perth, Australia, is far from Silicon Valley).[3]

We pitched to hundreds of investors, getting rejected time and time again. . . . I was quite literally living on my brother’s floor.[4]

Rejection hurts a lot, but failure was never an option. . . . For better or worse, when I set my mind to something I don’t give up very easily at all. Being rejected a lot in our initial stages just meant that I had to try harder and refine my strategy.[5]

Similarly, Perkins sets bold goals:

One of our values at Canva is to set crazy big goals and make them happen. . . . And I think that helps to carry the whole company because, as they’re dreaming together, and we’re all dreaming about what is that next big thing . . . that’s really exciting and motivating because people want to be part of something that’s bigger than themselves.[6]

A second personality trait, agreeableness, is evident in the way Perkins is an excellent listener, attuned to the needs of those around her. Indeed, the idea for her user-friendly design software came from her observations while teaching graphic design courses at a university. She noticed how difficult it was for students to learn to use the available software.

People were really struggling with basic programs like Photoshop and InDesign. . . . It would take them six months just to learn the bottom level that you need to even begin a design. I realized that I could create a tool online that’s collaborative and really easy to use.[7]

This insight prompted her to co-found Fusion, a company that developed software to help high schools do lay-outs for their yearbooks. The success of Fusion gave her the confidence, and experience, to start Canva.

Perkins’s agreeableness is also evident in her caring orientation, demonstrated by the company’s philanthropic work. Canva participates in the 1% Pledge to donate to charity 1 percent of its product (e.g., it provides products for free to non-profits and schools); company time (“every year, our team [members] get time to actually go and do things that have a positive impact in their local community. We have a whole range of programs set up to do so”[8]); profit; and equity. Going further, in 2023 Perkins and co-founder Cliff Obrecht committed to donating most of their personal equity in Canva (30 percent) to charities around the world:

The decision to give away the vast majority of our equity . . . it wasn’t really a choice. It was like . . . who needs billions of dollars? Literally no one needs billions of dollars for anything. We believe that customers and investors and our team really want to be working for companies and investing in companies and joining companies that are doing good things for the world.[9]

Perkins also demonstrates openness to experience. During the early years when she was seeking investors, she learned about an event with investors who enjoyed kitesurfing (i.e., standing on a surfboard holding onto a kite to propel you through the water). Perkins was adventurous enough to learn how to kitesurf, thinking this might help her get investors: “If you get your foot in the door just a tiny bit, you have to kind of wedge it all the way in.”[10]

Of course, Perkins’s leadership behaviors also helped Canva immensely. Showing task-oriented leadership behavior, Perkins developed structures that address social and ecological externalities of the firm (e.g., the 1% Pledge). This is also evident in how her emphasis on goals has shaped Canva’s structure.

We structure our whole company around goals. The old school hierarchies of years gone by with rigid structures and hierarchies were certainly not made for rapidly growing startups. We structure each team around “crazy big goals” with a lot less emphasis on titles. Every team has a goal and then celebrates when they hit that goal.[11]

This connects with her relationship-oriented leadership behavior, where Perkins has long been aware of the importance of fostering community and belongingness at work. For example, she believes in the importance of people having lunch together, and feels it is an important opportunity of bonding.

Having lunch together is one of strongest things you can do for culture. When people are feeling strong friendships and social networks, they feel part of something. We used to have lunch around mum’s living table. Now we have a chef who comes in and cooks.[12]

Perkins’s change-oriented leadership behavior combines an emphasis on achieving organizational goals with anticipating and serving stakeholder needs, what she calls her two-step plan:

Step one, build one of the world’s most valuable companies. And step two, do the most good we can do. And I think that that has been a really unifying force for our company as well because it means that people are coming to Canva who actually care about having a positive impact and care about things that are bigger than themselves.[13]

Finally, Perkins is aware of how she has needed to change her leadership style over time:

I’ve been working toward the vision of Canva and this journey for more than 10 years now, and one of the most important things I’ve learned is that different stages of a business require different types of leadership.”[14]

In the early days, we didn’t have our values written down. We just kind of were sitting around the table and everyone could talk to each other and everyone kind of knew what everyone else was doing at all times. But then once we grew from everyone being around the same table and understanding what everyone’s working on implicitly we needed to cement those values into something that everyone could see and feel. So, the day that someone starts [to work at Canva], they’ll know that we’ve got their back if they make a decision that’s in line with our values. And so we went through a bit of a process to ensure that we actually wrote those things down.”[15]

15.1. Introduction

Leading is one of Fayol’s four functions of management (alongside planning, organizing, and controlling; see Chapter 1). Leading is the process of influencing others so that their work efforts lead to the achievement of organizational goals. Leadership may be the most researched topic in all the social sciences, but there is still very much to learn. As with each of the four functions of management, sometimes members other than the formal manager perform the leading function. In fact, in most organizations there are many such informal leaders and, as we shall discuss, different “leadership substitutes” that can reduce the need or opportunity for a manager to perform the leading function.

A key challenge for students of leadership is measurement. How do you decide how good someone is as a leader? This chapter will focus on three of the most common measures used by leadership researchers. The first—leader effectiveness—is commonly measured by combining the ratings of a leader from the leader’s followers, peers, and managers.[16] Because these ratings of leadership effectiveness are based on others’ perceptions rather than based on objective performance measures, they may be influenced by the raters’ implicit understandings of “what makes a good leader.”[17] For example, research suggests that people today are still more likely to assume that leaders are male,[18] and that people who are extraverted are more likely to become leaders.[19] In fact, each of us has a detailed image in our head of what we think a leader is. When you hear the word “leader,” what comes to your mind? Do you picture someone old or young? Male or female? Outgoing or shy? Research has shown that each of us has a script defining the ideal leader, and this script reflects our experiences, our culture, and the environment around us. The better a person matches our script, the more positively we respond to their leadership. We are more likely to agree with a leader who matches our script, and we tend to evaluate them more positively. And most of these effects happen subconsciously. In other words, we don’t know we’re doing it. For example, if a follower’s script for an ideal leader describes someone who is “mature” (perhaps in their forties or fifties), then a leader who is younger or older will be at a disadvantage. The follower may not be aware of doing so, but they will judge a “too-young” leader more harshly and be less likely to give them the benefit of the doubt.

A second commonly used measure looks at follower satisfaction with the leader. This measure focuses on the perceptions of followers regarding the type and quality of relationship they have with their leaders. This measure is important because influencing followers is at the core of what it means to be a leader: no one can be a leader unless they have followers. Of course, a problem with this measure is that followers may be most satisfied with leaders who are the least demanding of them, and thus may not be particularly effective at meeting organizational goals.

The third measure is group performance, which has the advantage of being based on objective outcomes. However, groups may perform well in spite of having a poor leader. Such groups may have members who play various informal leadership roles to fill in or compensate for the lack of a competent formal leader. Imagine a group led by an emotionally volatile leader, where the members organize to support each other and ensure the group performs well. In contrast, it can also be the case that a group performs poorly despite having a great leader. For example, a sports team may have a great coach, but lousy players.

This chapter will review what scholars have learned about leadership, focusing on traits, behaviors, and contingencies. As always, our discussion will highlight differences between Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) perspectives as appropriate.

15.2. Leadership Traits

Traits are personal characteristics that are relatively stable. Early research in leadership sought to identify characteristics that differentiated leaders from non-leaders by analyzing great leaders.[20] Indeed, over the years researchers have examined hundreds of traits to see if they are related to leadership. However, recall from Chapter 14 that the Big Five personality traits have been the most studied: (1) Conscientiousness (being achievement oriented, responsible, persevering, dependable); (2) Agreeableness (being good-natured, cooperative, trustful, caring, gentle, not jealous; (3) Extraversion (being sociable, talkative, assertive, adventurous); (4) Emotional stability (being calm, placid, poised, not anxious or insecure); and (5) Openness to experience (being intellectual, original, imaginative, cultured, curious).

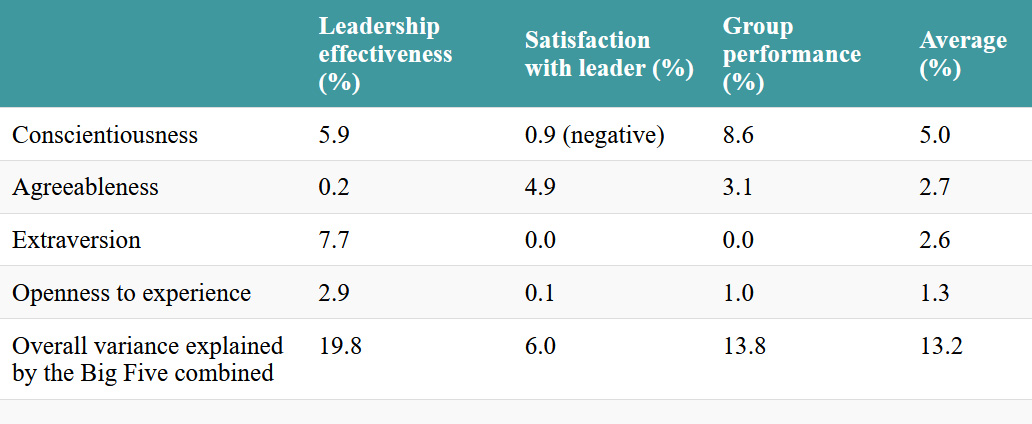

As shown in Table 15.1, taken together, the Big Five personality traits account for almost 20 percent of the variance in their perceived leadership effectiveness (i.e., first column in table). In other words, if you know the personality trait scores of leaders you can use that information to make more accurate predictions about how effective they will be perceived to be. The most important Big Five trait is extraversion, which alone accounts for 7.7 percent of the overall perceived effectiveness of leaders. The second most important personality trait is conscientiousness (5.9 percent of total variance). Emotional stability (3.1 percent) and openness to experience (2.9 percent) are also significant.[21]

Table 15.1. Personality traits and measures of effective leadership

When it comes to followers’ satisfaction with their leader (second column), the Big Five account for only 6.0 percent of the variance, with the biggest contribution coming from agreeableness (4.9 percent), and much less coming from conscientiousness (0.6 percent) and emotional stability (0.4 percent). It is interesting to note that the more conscientious a leader is, the less satisfied followers are. This suggests that followers’ satisfaction with leaders is lower when working for achievement-oriented leaders.

Finally, leader traits account for a total of 13.2 percent of the variance of group performance (third column). Here the most important trait is conscientiousness, which explains 5.0 percent of the variance. The second most important personality trait is agreeableness (2.7 percent), followed by emotional stability (1.5 percent) and openness to experience (1.3 percent). What may be unexpected is that emotional stability has a negative effect on group performance, which suggests that having an emotionally volatile leader may actually offer a small benefit to group performance.

15.2.1. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Leadership Traits

Each personality trait is important for each of the three approaches to leadership, but some traits may be more important for some approaches than for others. For example, as discussed in Chapter 14, agreeableness may be more relevant for SET leaders than for FBL leaders, given that agreeableness has a positive effect on enhancing social well-being but not on motivation to work for financial well-being.[22]

More generally, note that when leaders do not match the dominant social scripts for what constitutes an effective leader, they will have to work harder to gain trust and support from followers. Because FBL has historically been the dominant management approach and TBL management is currently the most common approach among large, high-profile organizations, many people may have “profit maximizing” as a part of their generic script for what constitutes effective business leadership. If so, then SET leaders might be perceived as less effective, because they fail to match that aspect of their followers’ scripts. However, in keeping with the social construction of reality (see Chapter 2), if SET-oriented leaders become more common and gain higher profile, we can expect that generic leadership scripts will change to place greater emphasis on socio-ecological well-being.

Test Your Knowledge

15.3. Leadership Behaviors

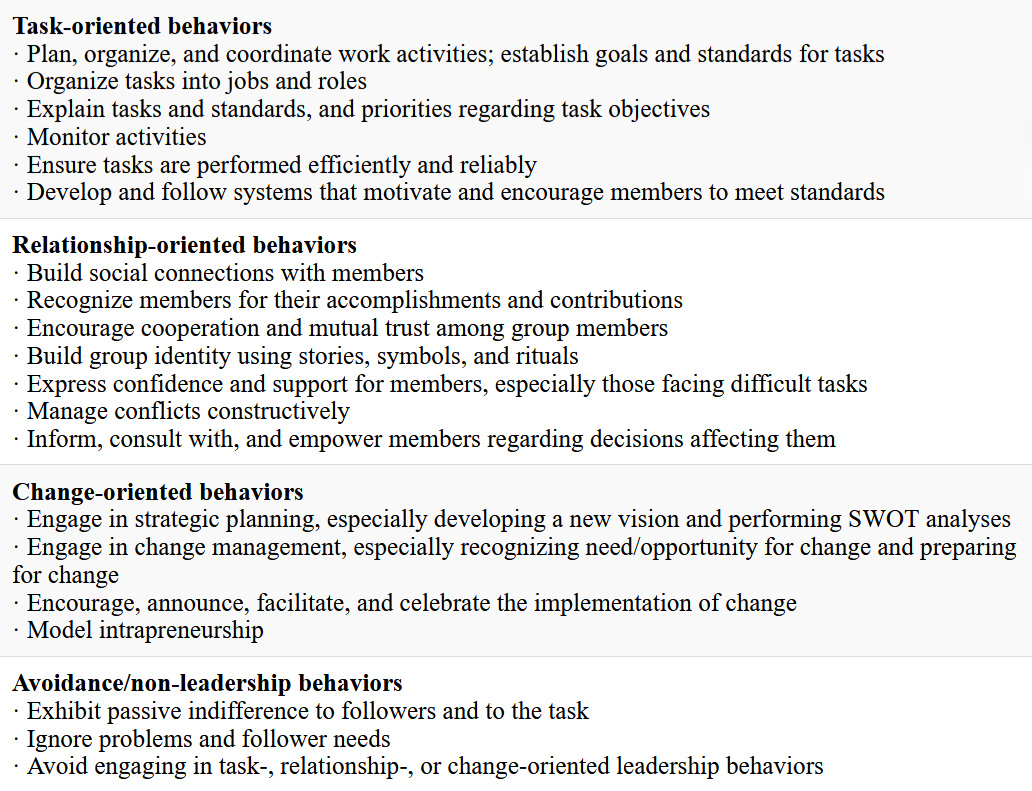

Researchers have studied well over 100 different categories of leader behaviors, many of which overlap with each other. However, as summarized in Table 15.2, there is some agreement that all these behaviors can be combined into three different clusters or types of leadership behavior (task-oriented, relationship-oriented, and change-oriented), and a fourth type that might be called non-leadership behavior (avoidance).[23]

Table 15.2. Main types of leadership behaviors

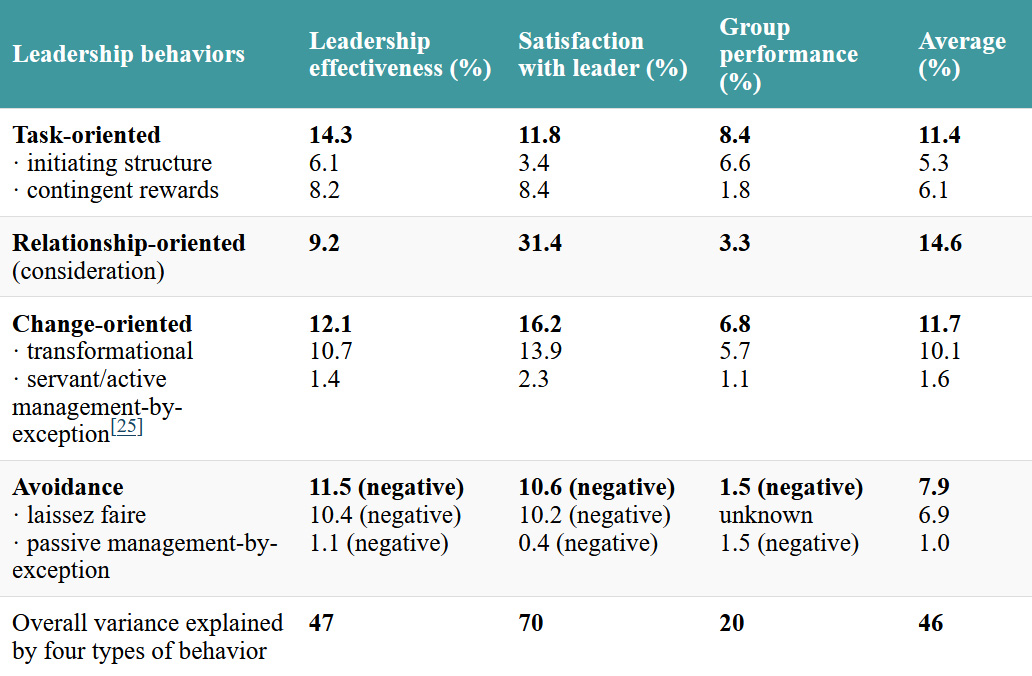

As shown in Table 15.3, empirical research suggests that taken together, these four leadership behaviors account for almost half (46 percent) of the variance across all three measures of leadership.[24] In other words, how well and how appropriately you exhibit these four behaviors will explain about half of your effectiveness as a leader. That is something worth learning! We will look at each in turn.

Table 15.3. Leadership behaviors and measures of effective leadership

Note: [25]

15.3.1. Task-Oriented Leadership Behaviors

Task-oriented behavior involves designing, implementing, and explaining organizational structures and systems that enable and motivate members to perform their tasks. Task-oriented behaviors are often associated with transactional leadership, so named because it focuses on the instrumental transaction that takes place between self-interested members and their employer, who offers benefits in exchange for members performing tasks assigned to them. The focus here is on the task itself, and not on the social relationships in the workplace.

Task-oriented behaviors often involve initiating structure and using contingent rewards.[26] Initiating structure describes behaviors like determining tasks and roles and assigning them to members, coordinating members’ actions, and maintaining the standards for task performance. Contingent rewards are rewards that are linked to the performance of a specific behavior or outcome. Associated leadership behaviors include clarifying rewards, helping followers based on their effort, and recognizing and rewarding achievements.[27]

On average, task-oriented behaviors explain about 10 percent of the variation in measures of leader effectiveness (14 percent), follower satisfaction with the leader (12 percent), and group performance (8 percent). Compared to the other types of leader behaviors, task-oriented behaviors make the greatest contribution to group performance, where task-oriented behavior explains almost half of the total effect of all the leader behaviors combined. This is especially true for initiating structure, which accounts for about one-third of the effect that leader behavior has on group performance. In other words, when it comes to facilitating group performance, leaders should focus on the perhaps somewhat mundane work of developing well-functioning structures and systems, as this is more important than relationship- or change-oriented behaviors. In contrast, focusing on contingent reward behaviors describes over 8 percent of variation in leadership effectiveness and satisfaction with leader scores, but less than 2 percent of group performance.

15.3.2. Relationship-Oriented Leadership Behaviors

Relationship-oriented behavior involves showing concern and respect for group members, being friendly and approachable, treating other members as equals, and being open to their input.[28] Mutually trusting relationships, where leaders and followers both expect the best from each other, are ideal and influence a vast range of outcomes, including turnover, job performance, commitment, satisfaction, and willingness to help.[29] In exhibiting relationship-oriented behaviors, leaders not only improve their own relationships with followers but also encourage members to focus on the well-being of the group as a whole.[30] Relationship-oriented behaviors are often described using the term consideration. Consideration includes listening to, defending, consulting with, accepting suggestions from, and doing personal favors for followers.[31] Some of the key behaviors of leaders that rank high on consideration include focusing on followers’ strengths, differentiating among followers, providing individual attention to each follower, and teaching and coaching followers.[32]

Consideration goes a long way when explaining how satisfied followers are with their leader, explaining almost one-third of the variance (31 percent). Consideration is also important for explaining leadership effectiveness (10 percent); it is least important for explaining group performance (3.3 percent).

Test Your Knowledge

15.3.3. Change-Oriented Leadership Behaviors

Change-oriented behavior involves monitoring and understanding the work unit’s larger environment, discovering innovative ways of working within it, and promoting the implementation of major changes in strategy, structures, and systems, or in the array of goods and services that are offered.[33] Change-oriented leadership behaviors are an important part of intrapreneurship (see Chapter 13). Among scholars who research leadership, the most common example of change-oriented leadership is called transformational leadership.

Transformational leadership has been described in many different ways by many different authors. However, there is some agreement that it has at least four components, known as the 4 I’s: intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, idealized influence, and individualized consideration.[34] Of these, the first two in particular are related to change-oriented behavior, and the second two are more aligned with relationship-oriented behavior, with some reference to task-oriented behavior in the second component (setting standards, defining tasks).

- Intellectual stimulation involves leaders challenging assumptions, taking risks, encouraging follower creativity, and soliciting their ideas. This behavior prompts followers to see problems in a new light and develop novel or creative solutions for making changes. It includes suggesting new ways of doing things, seeking different views, seeing things from different angles, and re-examining assumptions of how things are done.[35] First principles thinking—which breaks down complex problems into their essential fundamental parts—exemplifies this approach.[36]

- Inspirational motivation involves leaders articulating a vision that followers find compelling. It also includes challenging members via setting high standards, demonstrating optimism that members will be able to achieve the goals, and providing members with a sense of meaningfulness for the tasks they perform.[37] In short, transformational leaders promote changes that are engaging and meaningful.

- Idealized influence (sometime called charisma) involves leaders behaving in admirable ways that increase followers’ identification with the leader, such as making self-sacrifices in order to benefit followers, or demonstrating exemplary courage or dedication. (This is related to referent power described in Chapter 14). Elon Musk, co-founder and CEO of Tesla, exemplified this behavior when sleeping on the factory floor for months while ramping production of the Tesla Model 3.[38]

- Individualized consideration involves leaders listening and attending to the concerns and needs of each follower, and providing coaching, mentoring, support, and encouragement as appropriate. While Musk is known for having little patience for failure, his colleagues laud his support and philosophy to “serve your team.”[39]

Many other types of leadership that overlap with transformational leadership have been identified, including charismatic leadership, authentic leadership, ethical leadership, spiritual leadership, and servant leadership. While there are important conceptual differences between these types, researchers have had a difficult time discriminating between them in terms of observable behaviors. Moreover, these other types of leadership seem largely redundant with transformational leadership in terms of their outcomes. One exception seems to be servant leadership, which has behaviors that do offer a value-added contribution that goes beyond transformational leadership.[40]

Servant leadership shares many components with transformational leadership, including a focus on identifying new opportunities to solve problems (intellectual stimulation), adding meaning to task performance (inspirational motivation), being a role model who is able to forgo self-interests to benefit others (idealized influence), and attending to the concerns and needs of followers (individualized consideration). Where servant leadership differs from transformational leadership is in the leader’s focus. Transformational leaders concentrate on building follower commitment to meet the objectives of the organization, whereas servant leaders focus on serving their followers and others.[41] Servant leaders actively promote the well-being of others even if this does not maximize financial well-being for the firm. According to Robert Greenleaf, who coined the term servant leadership,[42] the essence of servant leadership involves three interrelated components:

- First, servant leaders help others to “grow as persons.” To grow as persons fosters community because it emphasizes and nurtures the connection among people (a person is a part of a community). This is different from an understanding of growing as individuals defined as being distinct or apart from others.[43]

- Second, servant leaders want others to become “healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, [and] more likely to themselves become servants.” Servant leaders model service, treat employees and others with dignity, and encourage them to do likewise.[44]

- Finally, servant leaders seek to have a positive effect on—and refuse to have a negative effect on—the stakeholders who are “the least privileged in society.” Servant leaders have a special concern for facilitating changes that improve the situation for people who are particularly disadvantaged by the status quo, both within and outside the organization’s boundaries. Recall the example of how Greenleaf modeled servant leadership when he helped to increase the number of women hired at AT&T, where his role was to help his followers recognize the need for such a change and to develop those changes themselves (Chapter 13).

As shown in Table 15.3, most of the effects of change-oriented leadership are associated with behaviors that characterize the transformational leadership style. Of the 11.7 percent effect on change-oriented behaviors on average, most of it (10.1 percent) is attributed to transformational leadership. Of the 11.7 percent, only 1.6 percent is due to the addition of behavior associated with active management-by-exception, which, like servant leadership, includes anticipating task-oriented problems and proactively taking corrective actions.[45] Overall, leaders who exhibit behavior associated with both transformational and servant leadership styles are more effective than leaders who exhibit only a transformational style.[46] Taken together, as shown in Table 15.3, on average change-oriented leadership actions account for about 16 percent of satisfaction with the leader, 12 percent of leadership effectiveness, and 7 percent of group performance.[47]

Test Your Knowledge

15.3.4. Avoidance Leadership Behaviors

This type of leadership, sometimes called laissez-faire leadership, describes people who are officially given a leadership role but fail to take responsibility or fulfill their duties. Laissez-faire leaders do not engage in task-oriented, relationship-oriented, or change-oriented leadership behaviors. Avoidance leadership behaviors also overlap with passive management-by-exception leadership, which describes nominal leaders who avoid making decisions, delay in responding to requests, are often absent when needed, and react only to serious problems.[48]

As Table 15.3 shows, avoidance behavior has a negative effect on all measures of leadership effectiveness and explains over 10 percent of the variance in leadership effectiveness and satisfaction with leaders.[49]

15.3.5. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Leadership Behaviors

Leaders with FBL, TBL, and SET management approaches may use any combination of task-, relationship-, change-oriented, and even avoidance behaviors. However, we can expect some differences in how these behaviors are put into action within the three approaches to management.

With regard to task-oriented behaviors, all three approaches are interested in achieving efficiencies within the organization, but SET managers will be more attuned to socio-ecological externalities associated with how tasks are designed and the results of performing them. For example, all coffee shops will design tasks so as to brew a great-tasting coffee, which includes sourcing the coffee beans and energy to brew the coffee. An FBL approach will seek to source the least-expensive coffee beans and the least-expensive energy provider to brew the coffee. In contrast, a SET approach will seek to purchase fair trade beans and to install solar power to provide the electricity, even though this complicates tasks and may create additional expenses related to sourcing beans and powering the equipment. In short, SET leaders include socio-ecological externalities when thinking about costs and efficiency associated with the tasks performed by followers.

In terms of relationship-oriented behaviors, an FBL approach will focus on managing relationships in order to optimize followers’ motivation and performance, whereas a SET approach will be more attuned to developing relationships that provide a sense of community, belongingness, and meaningful work (see Chapters 5, 16, and 17). As will be described more fully in Chapter 16, there is a difference between managing social relationships to maximize follower efficiency and productivity (the FBL approach) and managing social relationships to develop work units that perform tasks well while creating a life-enhancing community (the SET approach). Hallmarks of creating a sense of community include fostering an ethic of care and embracing healthy conflict.[50] An ethic of care accepts that people are morally relational and interdependent; this ethic is evident when organization members have ongoing emotionally significant relationships and behaviors that value the experience, needs, and future growth of others in a nurturing and compassionate manner (see Chapters 5 and 17).[51] Practicing an ethic of care has become more challenging for leaders in an era of remote work and AI (Artificial Intelligence),[52] but is certainly evident in examples like Nathaniel De Avila at Velo Renovation (Chapter 9).

With regard to change-oriented behaviors, while all three approaches value transformational leadership, there will also be differences. This is most evident in terms of the content of changes being promoted. FBL and TBL approaches will focus on change-oriented behaviors that serve to maximize financial well-being, and the SET approach will be most likely to include behaviors that enhance socio-ecological well-being (see also Chapter 13).[53] Whereas FBL leaders will exhibit a traditional transformational leadership focus on building follower commitment to meet the objectives of the organization, SET leaders will also embrace a servant leadership focus toward followers and other stakeholders.

Finally, none of the three approaches support avoidance leadership behaviors. However, as with the other leadership behaviors described in the previous paragraphs, there will be differences in how this plays out. For example, FBL leaders who are exhibiting all the task-, relationship-, and change-oriented behaviors expected of them will avoid exhibiting some behaviors that are exhibited by SET leaders. Relatively speaking, FBL leaders will generally avoid what they perceive as inefficient and unnecessary task-oriented behaviors related to socio-ecological externalities, relationship-oriented behaviors related to ethics of care, and change-oriented behaviors related to improving the conditions for marginalized stakeholders.

15.3.6. Combining Traits and Behaviors

Research suggests that leader personality traits influence leader behaviors as follows:

- agreeableness has a positive effect on relationship-oriented behavior

- extraversion has a positive effect on change-oriented and relationship-oriented behavior

- conscientiousness and emotional stability both have a positive effect on change-oriented and task-oriented behavior

- openness to experience has a negative effect on task-oriented behavior

Combining information about leaders’ Big Five personality traits with information about how much they exhibit the four main types of leadership behaviors explains 57 percent of the variation in leader effectiveness ratings, 92 percent of follower satisfaction with leader, and 31 percent of group performance (average = 60 percent).[54] In other words if, for example, you know what a leader’s personality traits and leadership behaviors are, you have a very good idea of how satisfied followers will be with the leader (these two things explain 92 percent of the variance). However, that same information explains less than one-third (31 percent) of the variance of group performance. While 31 percent is still a significant number—demonstrating that leadership makes a difference—it also points out that there are many other contingencies that need to be considered to explain group performance. This observation brings us to the next section.

15.4. Leadership Contingencies

Just as our understanding of leadership improves when we consider both leadership traits and leadership behaviors, it can be improved even further by recognizing that the appropriate leadership behavior depends on the situation facing a leader. Researchers have developed contingency models of leadership, where the situation determines which leadership behaviors are most effective at maximizing productivity (FBL management) or optimizing socio-ecological well-being (SET management).

Leadership contingency theories recognize that a successful leadership style in one situation may not necessarily work in another situation. For example, a task-oriented leadership style may be appropriate to train new technicians but not for leading seasoned financial planners. Similarly, a leadership style well-suited to the demands of an army general is not likely to fit well with the demands of a university president. However, it is possible for a person to perform well as a general and then as a university president and then as president of the United States, as Dwight Eisenhower did. Contingency theories help to determine which leader behaviors work best in different situations.

In some cases, substitutes for leadership act as situational factors that reduce the need for leaders to exhibit task-, relationship-, and change-oriented leadership behaviors.[55] Specific characteristics of the task and work environment may substitute for the behaviors of leaders, neutralize the influence of leaders, or enhance the influence of leaders.[56] For example, task-oriented leadership behavior may not be necessary when experienced followers have mastered their task and/or when a task is highly formalized with specific policies and procedural rules. Experience, policies, and rules can all be seen as substitutes for task-oriented leadership behavior. Indeed, in such cases leaders who continue to exhibit task-oriented behaviors may annoy followers. This may be especially true in highly technical jobs and in supervising millennials.[57] Similarly, in highly cohesive teams or when followers perform work that they find intrinsically interesting, it may not be as necessary for the leader to exhibit relationship-oriented behavior in order to ensure productivity. Especially from an FBL perspective, redundant relationship-oriented leadership behaviors may seem to be an inefficient use of time and money, whereas SET managers exhibit an ethic of care even if it does not maximize productivity. Finally, change-oriented behaviors may be unnecessary when an organizational unit is operating in a highly stable environment. This is not to suggest that leaders are unnecessary in such situations, but rather that the need for specific leadership behaviors may be reduced in certain situations.[58]

Several contingency models explaining the relationship between leadership styles and specific situations have been developed. Among the most influential are Fiedler’s contingency theory, House’s path-goal model, and Hersey and Blanchard’s variations of situational leadership theories. These theories all focus on two dimensions of leader behavior: task-oriented and relationship-oriented.

15.4.1. Two-Dimensional Contingency Theories

Fred Fiedler’s 1967 theory of leadership, based on the premise that effective leadership depends on a match between leadership style and situational demands, was an important early study in developing a contingency approach to leadership.[59] He looked at three aspects of a situation: how much authority the leader has, how well structured the followers’ tasks are, and how good the relationships between leader and followers are. Combinations of these three aspects can make a situation more or less favorable for the leader. For example, a very favorable situation is one in which the leader has a lot of authority, the followers’ tasks are well-structured, and leader-member relations are good. A very unfavorable situation is one where the leader has very little authority, the followers’ tasks are poorly structured, and leader-members relations are poor. An intermediate situation is one where leader authority is high, task structure is low, and leader-member relations are good. Fiedler found that in situations that are either very favorable or very unfavorable for the leader, the task-oriented leadership style is the most effective, but in situations that are intermediate in favorableness for the leader, the relationship-oriented style is most effective. Fiedler believed that it was difficult for leaders to change their style, so it was important to place them in situations where their basic style was effective. More recent leadership theories tend to assume that leaders can change their style and, for example, that a leader can use both relationship-oriented and task-oriented behaviors.[60]

Path-goal theory, developed in the early 1970s by Bob House, focuses on what leaders can do to motivate and align employee behavior to achieve organizational goals.[61] Consistent with expectancy theory (Chapter 14), path-goal theory suggests that a leader can motivate followers by linking their efforts and behaviors to desirable outcomes. Followers will perform better if leaders give them

- a clear and accurate understanding of the performance goals they are expected to accomplish (requires task-oriented leadership);

- the confidence that they can achieve those goals if they invest enough effort (requires relationship-oriented leadership); and

- an understanding that achieving their performance goals will result in rewards that they value (requires task-oriented leadership).[62]

According to path-goal theory, managers will be most effective when they exhibit leadership behaviors that complement situational needs. The leader adds the most value by contributing things that are missing from the situation or need strengthening. In other words, leadership means getting done what needs doing but wasn’t already getting done.[63] Most research evidence supports the logic underlying the path-goal theory that employee performance and satisfaction are likely to be positively influenced when the leader adjusts to situational factors related to the employee and the work setting.[64]

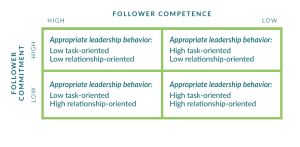

Finally, situational leadership theory provides a model that became particularly popular with practitioners.[65] Developed by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard, situational leadership theory integrates behavioral and contingency approaches to leadership, and adds a developmental element that explicitly looks at the changing needs of followers over time.[66] The model suggests that leaders can and should adjust their style of leadership behavior depending on the developmental level of followers to perform in a given situation.[67] A follower’s developmental level is seen to have two dimensions: (1) competence (how well a follower can perform the tasks required for their job), and (2) commitment (how willing or motivated the follower is to perform the task).[68] The developmental level of followers depends on factors like their maturity, expertise, work experience, and loyalty to their manager or co-workers.

Table 15.4. Four leadership styles depending on follower competence and commitment

As depicted in Table 15.4, this gives rise to four leadership situations, depending on the levels of followers’ competence and commitment. According to the model, the appropriate amount of task-oriented behavior leaders should exhibit varies along with follower competence: the less competent followers are, the more leaders should exhibit task-oriented behavior. A similar relationship exists between leaders’ relationship-oriented behavior and follower commitment: the less committed followers are, the more relationship-oriented behavior leaders should exhibit.

- High follower commitment/High follower competence: This describes situations where followers have become self-reliant achievers, having acquired the appropriate job-related competencies and high commitment to perform their tasks. This might refer to an employee with a lot of experience, skill, and loyalty. The model recommends that in response, leaders provide little task- or relationship-oriented behavior, thus allowing the follower to make decisions and take responsibility for those decisions (a “delegating” style). Permitting followers to self-manage in this way takes advantage of their skills and motivation while simultaneously reducing the time and financial costs required to manage employees. One might assume that followers would appreciate this leadership style, but research suggests that followers think it is appropriate only about 12 percent of the time, whereas leaders use it 42 percent of the time.[69]

- High follower commitment/Low follower competence: This describes situations when organizational members lack task-related knowledge to do their jobs but are enthusiastic and committed to acquiring it. This might be the case, for example, when a new, keen, but untrained employee joins a department. In response, the leader defines roles and gives instructions to the new employee regarding what, how, when, and where to do various tasks (a “directing” style). Specific task directions are given in this leadership situation, which requires more task-oriented than relationship-oriented behavior. According to followers, this combination of leadership behaviors is rarely needed or provided by leaders (less than 5 percent of the time).[70]

- Low follower commitment/High follower competence: This describes situations where organizational members have the competence necessary to perform the job but may lack motivation or confidence in their ability to perform. For example, a follower who has previously been micromanaged may have the skill but has become cautious and lacks the confidence or desire to take on more responsibility and act independently. Or perhaps a follower has grown bored of performing the tasks they have long mastered and needs a leader who realizes and enriches their work experience. In response, the leader adopts low task-oriented and high relationship-oriented behavior, encouraging such followers through providing affirmation and confidence in the follower’s abilities, practicing participative decision-making, and being approachable and friendly (a “supporting” style). According to followers, they need and receive this kind of leadership about 25 percent of the time.[71]

- Low follower commitment/Low follower competence: This describes situations where organizational members have neither good technical knowledge nor strong commitment. This might include employees who are undergoing a seemingly endless series of changes to their jobs, or recently hired employees who are faced with a long training period and for whom the excitement of a new job is wearing off. Or it might refer to typical employees who are not particularly committed to jobs they have not yet mastered. In these situations, the model recommends that the leader use high levels of both task- and relationship-oriented behavior to provide task directions, feedback, and affirmation in a supportive and convincing way (a “coaching” style). Followers suggest that they need coaching about 60 percent of the time but receive it only 33 percent of the time.[72]

15.4.2. Leadership Contingencies and Change

While earlier studies of leadership contingencies tended to focus on the two dimensions of task- and relationship-oriented leadership behaviors, more recently researchers have begun adding contingencies associated with change-oriented leadership behaviors. Indeed, today leadership research focuses on transformational leadership behavior ten times more frequently than it focuses on task- and relationship-oriented leadership behaviors.[73] As our understanding of change-oriented leadership has grown, so too has our understanding of the contingencies associated with it. For example, research suggests that

- the more turbulent the environment, the greater the need for change-oriented leadership behaviors;

- the greater the diversity among members in a work group, the greater the need for change-oriented (and relationship-oriented) leadership behaviors;

- the more problems there are in overall working conditions (e.g., related to workplace safety or pay), the greater the need for change-oriented (and task-oriented) leadership behaviors;[74]

- the more emphasis there is on flexibility in an organization’s culture and design, the greater the appropriateness of change-oriented leadership behavior.[75]

Research also suggests that there is interplay among the appropriate types of leader behavior as changes unfold over time. Change-oriented (transformational) leadership is particularly important in the early stages of a change process, such as when recognizing the need or opportunity for change, developing the mission and/or vision, and developing strategic plans and goals. The more a leader serves as a visionary role model in these early stages, the more likely followers are to appraise the change positively, and this positive attitude carries forward to the final phases of the change process. In contrast, task-based (transactional) leadership in the early stages of the change process has a negative effect on followers’ appraisals of the change. For example, introducing change by seeking to ensure compliance and consistency undermines followers’ support of the change.[76]

Shared leadership

It is important to note that leadership behaviors can be distributed, or shared, among the members of an organizational unit. In other words, it is not necessary for the formal leader of an organizational unit to be equally adept at task-oriented, relationship-oriented, and change-oriented leadership behaviors. Even key leadership behaviors within each of these three clusters can be shared. For example, consider how the behaviors associated with transformational leadership can be shared among members. One member may be particularly good at envisioning (being able to articulate a compelling vision, set high expectations, and model consistent behaviors), another member particularly good at enabling (being able to express personal support, empathize, and express confidence in people), and a third member particularly good at energizing (being able to demonstrate personal excitement).[77]

Research suggests that shared leadership may explain additional variance in a team’s performance compared to when leadership is provided by only a nominal leader.[78] This may be especially true when leadership is shared in the top management teams of new start-ups (see also Chapter 16).[79] Shared leadership increases ability and confidence within groups.[80] When groups face challenging situations, they can turn to members who have the necessary leadership expertise to deal with the situation and do not need to rely on a single, nominal leader to be expert at everything. Shared leadership can also provide greater opportunities for members to interact with, get to know, and be intellectually stimulated by their co-workers, which may increase their motivation, competence, and performance. Research also suggests that the relationship between shared leadership and a group’s performance becomes stronger the more the group’s work is knowledge-based and members work with each other interdependently (for more on interdependence, see Chapter 16).[81] While the sharing of task- and relationship-oriented leadership behaviors contributes to team effectiveness, the sharing of change-oriented leadership behaviors is particularly valuable.[82]

Test Your Knowledge

15.5. Entrepreneurship Implications

Just like other leaders, leaders of entrepreneurial ventures need to exhibit each of the three generic types of leadership behaviors: task-, relationship-, and change-oriented. The benefits from these three types of behaviors will vary based on the situation facing a leader; however, the situation facing entrepreneurial leaders is significantly different than for other leaders.[83] In general terms, all three types of leadership behavior are especially important because there are few precedents or leadership substitutes in new start-ups. For example, there may be no existing policies regarding tasks like how to hire a new employee or how to keep track of inventory. As well, there is no history of interpersonal relationships to draw upon within a new firm and with its key suppliers and buyers, and change is constant when many things are being done or developed for the first time. Given the sheer volume of leadership behaviors that need to be performed, it makes sense that new ventures perform best when there are multiple leaders or when leadership roles are shared among members.[84] We will discuss each of the three types of leadership behavior among entrepreneurs, starting with change-oriented leadership behavior, because of its central importance in entrepreneurship.

15.5.1. Entrepreneurship and Change-Oriented Behavior

Change-oriented behaviors are key when starting a new venture, where everything is new. Entrepreneurs engage in change-oriented behaviors by definition when they recognize the opportunity to start something new, develop a mission or vision for their new organization, and engage in strategic planning and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analyses. They can do this formally or informally (e.g., they may not write down the venture’s mission or vision statement, but the vision and mission will be evident in the actions of the entrepreneur over time). Similarly, the entrepreneur may not complete a formal SWOT analysis, but instead prefer to engage in strategic learning (as described in the Honda motorcycle case in Chapter 9).

Transformational leadership behaviors are particularly important for start-ups. Starting a new venture requires each of the four hallmarks of transformational leadership: (1) Inspirational motivation—leaders must articulate a vision that is compelling enough that stakeholders will want to support and participate in it; (2) Intellectual stimulation—leaders encourage followers to participate in identifying and creatively solving problems and seizing opportunities; (3) Idealized influence—leaders set the example for other members to be inspired by and to follow; and (4) Individualized consideration—this is especially evident in the relationship-oriented behavior entrepreneurial leaders exhibit.

As is the case for leadership more generally, we would expect SET entrepreneurs to engage in more servant leadership behaviors than their FBL and TBL counterparts.[85] Because servant leadership is more time-consuming and demands serving other stakeholders (especially the marginalized) from an FBL and TBL perspective, it may seem to be an inefficient way to get a new venture up and running. However, while it is true that servant leadership complicates and slows things down in the short term, it may offer advantages in the long run. For example, imagine that you are working for a non-government organization (NGO) in Bangladesh in the 1970s.[86] Further, imagine that agricultural practices in Bangladesh are hampered by a lack of irrigation, and most villagers drink water from hand-dug wells or ponds that are shared with bathing cows and water buffaloes. Cholera and diarrhea are common, and each year hundreds of thousands of deaths result from drinking contaminated water. The need for change is clearly evident. What leadership behaviors would you exhibit?

One option was pursued by several large NGOs that took decisive action, operating from a transformational leadership perspective. They drew on their knowledge of technologies that worked in other countries and opted to import and subsidize diesel-powered and cast-iron pumps to supply water for irrigation. Unfortunately, these imported technologies were resisted by farmers and failed to achieve the desired result. They were deemed too costly to purchase, required expensive fuel to operate, and could not be easily repaired locally when they broke down.

In contrast, a successful technology was introduced by a much smaller NGO using a servant leadership style. The entrepreneur was George Klassen, a North American engineer who had been working alongside Bangladeshi farmers in the fields for several years in a servant leader mode, contributing to community building and earning their trust. He was successful in building relationships and mutual understanding, but from an FBL and TBL perspective he had little “explicit” measurable success to show for his efforts (e.g., increase in calories of food energy produced, people fed). However, it was Klassen who eventually had the insight to develop what is called a “rower pump” (so named because operating it requires a motion that looks similar to rowing a boat). By experiencing the rhythms of the rural life and being attuned to the needs of the farmers, he had learned that they required a water pump that could be operated by one person, could be built out of local materials (e.g., bamboo shoots), and was an affordable “low-tech” option that could be serviced locally. As will be described below, coupled with appropriate task- and relationship-oriented behaviors from others in the NGO, this innovative rower-pump technology soon became the norm among Bangladeshi farmers.

15.5.2. Entrepreneurship and Task-Oriented Behaviors

Whereas a long-standing organization will generally have well-developed structures and systems related to tasks that need to be performed—for example, standard operating procedures, clear job descriptions, manuals and guidelines—the opposite is generally true for entrepreneurial start-ups. As a result, entrepreneurial leaders need to pay close attention to task-oriented behaviors. However, rather than focus on task-oriented behaviors to develop detailed and specific policies and guidelines—as might be the case for a mature bureaucracy—entrepreneurs should focus on developing flexible guidelines and policies (as might be the case in an adhocracy). In particular, as described in Chapter 11, because of low levels of standardization, entrepreneurs will need to spend more time with experimentation. And rather than relying on specialists to perform a narrow range of tasks, entrepreneurs will look for generalists who are sensitive to the need to perform a wide variety of tasks.

The importance of task-oriented behaviors, which are also clearly related to change- and relationship-oriented behaviors, can be seen in the introduction of the rower pump in Bangladesh. Once the best designs for the rower-pump had been fine-tuned and agreed upon, the operational challenge of bringing it to market arose. This task required a different set of leadership skills than Klassen’s, so it was handled by a more senior manager in the NGO (an example of shared leadership). Other staff at the NGO worked to piece together a network of local businesses to build, sell, and service the pump. This helped in the development of a local infrastructure with expertise in installation, repair, and inventory of parts. NGO workers also performed field tests and trained people on how to use the pump. In the early years, NGO workers also provided a subsidy for the pump but had clear plans to phase out its involvement within four years to ensure that the pump would be self-financing. Furthermore, the NGO planned to completely phase out their involvement after a period of five years.

Five years after the entrepreneurial venture was started, a critical mass of farmers was using the rower-pump technology (1,000 were sold), and the infrastructure had been developed to enable the further production, sale, and service of rower pumps. This provided the foundation for other entrepreneurs to get in on the action; “scripts” about how to build, sell, fix, and use the rower pump were reasonably well-developed. Copy-cat and clone rower pumps were introduced, and soon sales reached 50,000 pumps and it became the new normal among Bangladeshi farmers.

15.5.3. Entrepreneurship and Relationship-Oriented Behavior

Relationships are vitally important in all leadership situations, but they take on special importance for classic entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs are at a severe disadvantage if, when they start a new firm, they also have to spend time developing new relationships with their employees, suppliers, and buyers. This is one reason why entrepreneurial ventures are more successful if they are started by a group of people who have previous experience working together in the industry. Indeed, employees in start-ups are more likely to be there because they know the founders, as opposed to having applied for a job at an organization about which they know nothing. Because everything is new, relationships gain importance, since people need to be adaptive and trusting in rapidly changing situations.

The importance of relationships is clearly evident in the introduction of the rower pump in Bangladesh. Klassen’s good working relationship with farmers had two positive benefits. First, the farmers had learned to trust him and were motivated and willing to work alongside him in refining the idea of a rower pump. Second, Klassen benefited greatly from the knowledge that farmers shared with him as they developed and tested many different prototypes. The rower pump could not have been fine-tuned without the expertise and knowledge of both Klassen and the farmers. Whereas other NGOs had difficulties getting skeptical farmers to test and use their diesel-powered and cast-iron pumps, farmers were eager to work with Klassen with whom they had developed a trusting relationship over time. They experimented with different designs, talked about how to deliver the product, and learned from one another. They worked together and there was less resistance to change.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Knowledge about a leader’s Big Five personality traits (conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion, emotional stability, and openness to experience) can help to explain significant portions of their anticipated leadership effectiveness (20 percent), followers’ satisfaction with them as leader (14 percent), and group performance (6 percent).

- Knowledge about a leader’s four main leadership behaviors (task-oriented, relationship-oriented, change-oriented, and avoidance) can also explain significant portions of their anticipated leadership effectiveness (47 percent), followers’ satisfaction with them as leader (70 percent), and group performance (20 percent).

- The three key leadership behaviors are expressed differently by FBL and SET leaders.

- Task-oriented

- FBL: focus on efficiency, productivity, and profit

- SET: focus on productivity and socio-ecological externalities

- Relationship-oriented

- FBL: focus on relationships to motivate performance

- SET: focus on community, job satisfaction, and meaning

- Change-oriented

- FBL: focus on achieving organizational goals

- SET: focus on serving stakeholders/anticipating needs

- Task-oriented

- Important contingencies that influence which leadership behaviors are most appropriate in a particular situation include competence and commitment of followers, environmental turbulence, workgroup diversity, stage of the change process, and type of organization culture and design.

- Shared leadership means that less pressure is put on one person to have the expertise to play all the different leadership roles. It can make a greater impact on measures of team performance than the impact of the nominal leader.

- Entrepreneurs’ leadership takes place in a context where there are few pre-existing scripts and leadership substitutes, making each of the three leadership behaviors more crucial than in other contexts, thus making shared leadership especially important early in a new venture.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Do you think that most leaders basically have a fixed one-size-fits-all leadership style, or are they quite flexible as appropriate to the situation? Give examples to support your view.

- Consider the best boss for whom you have worked. What characteristics describe their leadership? Are the characteristics predominantly traits or behaviors?

- Identify a strength of a leader whom you know. Is it possible that this strength could also be a weakness? Explain.

- What are the pros and cons of a low task-oriented and low relationship-oriented leadership approach? Have you ever seen this leadership approach work well? Poorly? Describe. Do you think FBL and SET managers would engage in this behavior for different reasons? Explain. Do you think there would a difference in the likelihood that FBL and SET managers would engage this behavior? Explain.

- Given that shared leadership can make significant contributions to group performance, why is it not discussed more prominently in the media and in business schools? What does this tell us about our implicit theories of leadership? What sorts of self-fulfilling prophecies does it create? Do you think there is a difference between how receptive an FBL and a SET approach is to the idea of shared leadership? Explain.

- Now that you have read the chapter, go back to the opening case about Melanie Perkins. Do you think she is a servant leader? Explain. Would you like to work for and be mentored by her? Explain.

- Think about an entrepreneurial venture you might want to start. What sorts of personality traits do you think will be important to lead the start-up? Do you have those traits, and if not, what sorts of leadership substitutes could be used to make up for the deficiency? What leadership behaviors will be the most important to a successful launch? Consider the pros and cons of starting with a group of co-founders. What sorts of leadership skills would you want other members of your group to have that complement yours? What skills do you have that you would not want others to have?

- Forbes staff. (2024). Melanie Perkins: Redefining innovation and leadership in tech (2024, December 20). Forbes Britain. https://forbesbritain.com/melanie-perkins-redefining-innovation-and-leadership-in-tech ↵

- Forbes staff. (2024). ↵

- “Women make up only 2% of CEOs in venture-backed companies, a statistic Perkins is determined to change. At Canva, women comprise 41% of the workforce, far exceeding industry averages” (Forbes staff, 2024). ↵

- Miller, H. L. (2022, April 5). Melanie Perkins and the rise of the B unicorn, Canva. Leaders. https://leaders.com/articles/leaders-stories/melanie-perkins/ ↵

- Emphasis in original. Miller (2022). ↵

- Quote from around the 14-minute mark of Nolan, R. (Host). (2024, July 16). Canva CEO Melanie Perkins on growing an idea into a multibillion-dollar design company. Goldman Sachs Talks [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QIRLeqKxy8c ↵

- Soar, M. (2015, July). 10 minutes with Melanie Perkins co-founder and CEO of Canva. Marketing News, 50-56. ↵

- Around the 24-minute mark of Nolan (2024). ↵

- Melanie Perkins: Next Generation Leaders. (2023, May 24). Time [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-yhy1ZQU3Y. “Despite her accolades, Perkins remains humble and embraces simple living. During a trip to Turkey, Obrecht proposed with a engagement ring, reflecting their shared disdain for materialism” (Forbes staff, 2024). ↵

- Miller (2022). ↵

- Kerr, B. (2024, December 25). Melanie Perkins, making beautiful design simple for all. Open Source CEO. https://www.opensourceceo.com/p/melanie-perkins-deep-dive ↵

- Compiled from quotes in Kerr (2024). ↵

- Around the 15-minute mark of Nolan (2024). ↵

- Rote, L. (2019, November 26). Canva CEO Melanie Perkins on learning, leading, and self-care. SixtySix. https://sixtysixmag.com/canva-ceo-melanie-perkins-on-learning-leading-and-self-care/ ↵

- Around the 17-minute mark of Nolan (2024). ↵

- Liu, S, Mao, J., Li, N., & Yue, Z. (2024, September 20). Not the time to be humble: When and why leader humility enhances and deteriorates evaluations on leader effectiveness and satisfaction with leader. Journal of Management Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.13137 ↵

- Lord, R. G., Foti, R. J., & De Vader, C. L. (1984). A test of leadership categorization theory: Internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 34(3): 343–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(84)90043-6; Eden, D., & Leviatan, U. (1975). Implicit leadership theory as a determinant of the factor structure underlying supervisory behavior scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(6): 736–741. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.60.6.736; Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2004). Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: Factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(2): 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.293; Epitropaki, O., Sy, T., Martin, R., Tram-Quon, S., & Topakas, A. (2013). Implicit leadership and followership theories “in the wild”: Taking stock of information-processing approaches to leadership and followership in organizational settings. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(6): 858–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.10.005 ↵

- Nhà, N. C. (2024, August 4). Women in leadership: Is professionalism inherently male-dominated? Vietcetera International Edition. https://vietcetera.com/en/women-in-leadership-is-professionalism-inherently-male-dominated. ↵

- Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4): 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765 ↵

- Lord, R. G., De Vader, C. L., & Alliger, G. M. (1986). A meta-analysis of the relation between personality traits and leadership perceptions: An application of validity generalization procedures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3): 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.402 ↵

- Table 15.1 is based on Table 3 Derue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N. E. D., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta‐analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1): 7–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01201.x ↵

- Marcus, J., & Roy, J. (2019). In search of sustainable behaviour: The role of core values and personality traits. Journal of Business Ethics, 158: 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3682-4 ↵

- Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Pearson. Table 15.2 also draws from Derue et al. (2011); and Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. (1999). Re‐examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 72(4): 441–462. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317999166789 ↵

- Table 15.3 based on Table 4 in Derue et al. (2011). ↵

- As will be described below, research suggests that servant leadership adds more than 10 percent to the effectiveness of practicing transformational leadership behaviors alone: Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2016). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44(2): 501–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316665461. Washington et al. found servant leadership to be related to transformational leadership, as well as to active management-by-exception and to contingent rewards: Washington, R. R., Sutton, C. D., & Sauser W. I., Jr. (2014). How distinct is servant leadership theory? Empirical comparisons with competing theories. Journal of Leadership, Accountability & Ethics, 11(1): 11–25. http://www.na-businesspress.com/JLAE/SauserWI_Web11_1_.pdf. Active management-by-exception is often linked to task-oriented leadership (e.g., Derue et al., 2011), but in Table 15.3 it is reported under change-oriented leadership because, it seems to us, it represents proactive changes initiated by the leader (e.g., anticipating problems and taking corrective action). Thus, in this table the contribution made by servant leadership consists of the contribution made by active management-by-exception. ↵

- “Both initiating structure and contingent reward describe leaders as being clear about expectations and standards for performance, and using these standards to shape follower commitment, motivation, and behavior” (Derue et al., 2011: 16). ↵

- Yang, F., Chen, G., Yang, Q., & Huang, X. (2023). Does motivation matter? How leader behaviors influence employee vigor at work. Personnel Review, 52(9): 2172–2188. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2021-0734 ↵

- Derue et al. (2011). ↵

- Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6): 1715–1759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280; Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader-member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6): 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.827 ↵

- Özkan, O., Üzüm, B., Çakan, S., Güzel, M. & Gulbahar, M. (2023). Exploring the outcomes of servant leadership under the mediating role of relational energy and the moderating role of other-focused interest. European Business Review, 35(8): 285–305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2022-0218 ↵

- Yukl (2013). ↵

- Avolio et al. (1999). ↵

- Yukl (2013). ↵

- These four come from a model in Bass (1985) building on Burns (1978). Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership & performance beyond expectations. Free Press; Burns, J. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row. The overview provided here draws from Anderson, M. H., & Sun, P. Y. (2017). Reviewing leadership styles: Overlaps and the need for a new “full‐range” theory. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1): 76–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12082; and Yukl (2013). ↵

- Avolio et al. (1999). ↵

- Tubis, N. (2023, September 13). First principles thinking: The blueprint for solving business problems. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescommunicationscouncil/2023/09/13/first-principles-thinking-the-blueprint-for-solving-business-problems/. ↵

- This review comes from Anderson & Sun (2017). ↵

- Carter, T. (2024, January 25). Elon Musk warns Tesla workers they’ll be sleeping on the production line to build its new mass-market EV. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-warns-tesla-workers-challenging-production-mass-market-ev-2024-1 ↵

- Schwantes, M. (2023). Elon Musk says what separates Great Leaders from the Pack comes down to 3 words. Inc. https://www.inc.com/marcel-schwantes/elon-musk-says-what-separates-great-leaders-from-pack-really-comes-down-to-3-words.html. ↵

- Hoch et al. (2016). ↵

- Stone, A. G., Russell, R. F., & Patterson, K. (2004). Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(4): 349–361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01437730410538671. See also Hoch et al. (2016). ↵

- Greenleaf, R. (2002). Servant leadership. Paulist Press. (Originally published 1977) ↵

- Page 718 in Dyck, B., & Schroeder, D. (2005). Management, theology and moral points of view: Towards an alternative to the conventional materialist-individualist ideal-type of management. Journal of Management Studies, 42(4): 705–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00516.x. See also discussion of ethics of care later in this chapter, and in Winston, B. E., & Ryan, B. (2008). Servant leadership as a humane orientation: Using the GLOBE study construct of humane orientation to show that servant leadership is more global than Western. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(2): 212–222. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228620739_Servant_leadership_as_a_humane_orientation_Using_the_GLOBE_study_construct_of_humane_orientation_to_show_that_servant_leadership_is_more_global_than ↵

- Ehrhart, M. G. (2004) Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 57(1): 61–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02484.x; Graham, J. W. (1991). Servant-leadership in organizations: Inspirational and moral. The Leadership Quarterly, 2(2): 105–119. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/1048-9843(91)90025-W; Hassan, S., Gull, M., Farasat, M., & Asif, R. (2023). Servant leadership and employee well-being in sustainable organizations: A self-efficacy perspective. Journal of Excellence in Management Sciences, 2(2): 100–111. https://journals.smarcons.com/index.php/jems/article/view/142 ↵

- Washington et al. (2014). As described in an earlier footnote, this study found servant leadership to be related to transformational leadership, as well as to active management-by-exception and to contingent rewards. Active management-by-exception is often linked to task-oriented leadership, but we add it to change-oriented leadership because, it seems to us, that it represents proactive changes initiated by the leader. ↵

- On average, servant leadership “added about 12% to the variance explained in the measures beyond that explained by transformational leadership alone.” (Hoch et al., 2016: 21). ↵

- Interestingly, the relative proportion of the effect of servant leadership versus transformational leadership is slightly larger for group performance (19% = 1.1/5.7) than for leader effectiveness (15% = 1.4/10.7) and satisfaction with leader (17% = 2.3/13.9). This may suggest that the merits of servant leadership are more pronounced in the actual performance of a group than in the perceptions of raters. In other words, our implicit leadership theories and scripts may prevent us from appreciating the merits of serving others, but despite this its merits are evident in our performance. The lack of appreciation for servant leadership is also highlighted in the story taken from Hermann Hesse’s novel Journey to the East, which Greenleaf used to describe the essence of servant leadership. In this story, a group of travelers enjoy success and good cheer along their journey without much notice of a faithful servant, Leo, who does the menial but necessary tasks and encourages the others with his positive spirit and song. Leo is, to a large degree, invisible to the traveling party, but after he leaves the party his leadership role becomes obvious to everyone when the group falls into disarray and the journey is forsaken. One of the travelers, after years of wandering aimlessly, meets up with Leo again, only to find out that among his people Leo is recognized as a great and noble leader. Hesse, H. (1956). The journey to the East (H. Rosner, Trans.). Picador. ↵

- Avolio et al. (1999). Note that in Table 15.3, active management-by-exception is related to servant leadership. ↵

- Avoidance explains less than 2 percent of the variance of group performance, but this is likely due to the fact that having inadequate data to determine the effect of laissez-faire leadership on group performance. ↵

- Lansing, A. E., Romero, N. J., Siantz, E., Silva, V., Center, K. Casteel, D., & Gilmer, T. (2023). Building trust: Leadership reflections on community empowerment and engagement in a large urban initiative. BMC Public Health 23: 1252. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15860-z ↵

- Lawrence, T. B., & Maitlis, S. (2012). Care and possibility: Enacting an ethic of care through narrative practice. Academy of Management Review, 37(4): 641–663. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.5465/amr.2010.0466 ↵

- Villegas-Galaviz, C., & Martin, K. (2024). Moral distance, AI, and the ethics of care. AI & Society, 39: 1695–1706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01642-z ↵

- Boeske, J. (2023). Leadership towards sustainability: a review of sustainable, sustainability, and environmental leadership. Sustainability, 15: 12626. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su151612626 ↵

- Derue et al. (2011). Note that these combined percentages of variance explained are not simply the summing of the variance explained in Tables 15.1 and 15.3. In some cases, combining the two creates redundancies and lowers the overall variance explained (leader effectiveness and group performance) in other cases it increases variance explained (satisfaction with leader). ↵

- Kerr, S., & Jermier, J. M. (1978). Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 22(3): 375–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(78)90023-5 ↵

- Kerr & Jermier (1978). ↵

- Ryan, S., and Cross, C. (2024). Micromanagement and its impact on millennial followership styles. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(1): 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2022-0329 ↵

- Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Kerr and Jermier’s substitutes for leadership model: Background, empirical assessment, and suggestions for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 8(2): 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(97)90012-6 ↵

- Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. McGraw-Hill. ↵