Part 4: Leading

14. Motivation

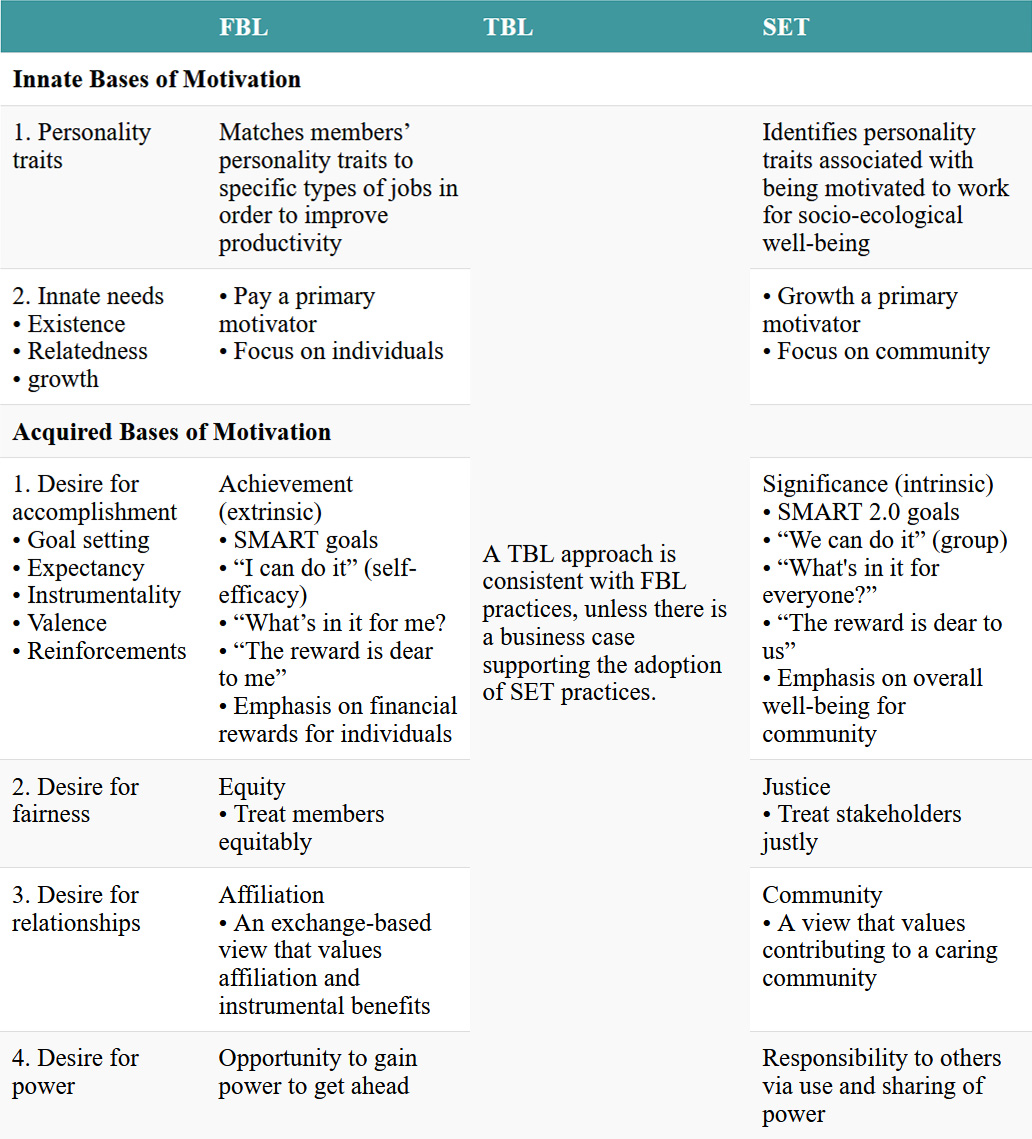

Chapter 14 provides an overview of innate and acquired bases of motivation, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain what motivation is and why it is important.

- Identify innate needs and personality traits everyone is born with, and describe how these are related to motivation.

- Describe the four basic acquired needs and explain how each is related to motivation.

- Describe differences between FBL/TBL and SET approaches to motivation.

- Understand the psychological and environmental factors that motivate entrepreneurs to start new businesses.

14.0. Opening Case: Motivational Sneakers

When managers look for ideas to energize people in their organizations, they often invite motivational speakers. However, to truly engender long-term motivation, perhaps they should look for lessons from motivational sneakers.[1] In particular, there is much to learn about motivation from Veja, a French firm that may provide the most sustainable sneaker on the planet. The word veja means “look,” inviting consumers to look at not only the sneakers but also the socio-ecological externalities that are built into sneakers. Veja has no advertising budget, but the company has been profitable and experiencing healthy growth since its launch in 2004, enjoying shout-outs from celebrities like actress Emma Watson and football star David Beckham.

Veja was started by François-Ghislain Morillion and Sébastien Kopp, who, in 2003 at the age of twenty-five, became disillusioned with the best practices of business as usual when they were doing a social audit for a French fashion brand in a Chinese factory:

We spent three days among the workers: they looked pale and tired, but the factory was clean, and the working conditions seemed pretty good. Everything went well with the audit, until we asked to see the living quarters. At first, the direction [management] refused, but after insisting and arguing, they opened the doors. We found ourselves in a 25 square meter room where 32 Chinese workers were sleeping together, stacked in 5-level bunk beds. And in the middle of the room, only a hole that served both as a shower and a toilet. On that day, we realized globalization had gone wrong.[2]

Kopp and Morillion, two extraverted and conscientious university graduates who had been friends since age fourteen, were open and eager to find better ways of doing business. In particular, they were motivated to start a sustainable business that addressed humankind’s physical, social, and human fulfillment needs.

After exploring a variety of ideas, they eventually decided that they should reinvent sneakers, a product they loved and which they felt was symbolic of their generation. An important insight was learning that 70 percent of the costs associated with the sneakers produced by big brands go into advertising and communication, and only 30 percent account for the actual raw materials and production. So they decided to produce a sneaker where all the costs would go into the raw materials and the people making the sneakers, and to not spend any money on advertising.[3]

Kopp and Morillion had previously worked with a fair trade company and spent several years traveling the world, looking at socio-ecological externalities associated with mining operations, sweatshops, and small-scale agriculture. With this background knowledge, and working with non-government organizations (NGOs) to help identify suppliers along the way, they chose Brazil to source and produce their shoe. Brazil has the world’s best supply of wild rubber, a good supply of organic cotton, and factories where workers are paid a living wage.

Veja and its stakeholders are motivated to enable people to meet their basic needs for physical and social well-being, and have developed practices that treat people and the planet fairly. For example, Veja pays its suppliers of raw material above–market rates and helps them enhance ecological well-being. Its 320 cotton farmers receive twice the market rate for their crop and have been trained to use agronomic practices that minimize soil erosion. Veja also pays a premium rate to the sixty families of seringeiros (rubber tappers) who supply its rubber, so that the tappers do not need to clear the forest (and thereby degrade the land) in order to supplement their incomes with cattle or other crops.[4] In France, Veja works with an NGO that provides employment for the chronically underemployed, who are responsible for the logistics of receiving and warehousing shoes from Brazil and distributing them to various retailers and online customers.

Veja and its stakeholders are further motivated to build relationships and community, both at work and beyond. For example, its factory workers in Brazil are paid a living wage (16 percent above minimum wage) while also having weekends off, shorter workdays on Fridays, four weeks of vacation, overtime pay, and bonuses. Veja also enables new employees in France to visit the factory in Brazil, build intercultural relationships, and gain a first-hand understanding of who manufactures the sneakers and where they come from. Veja designs and maintains its website to create greater transparency, thereby building virtual relationships of sorts between its customers and suppliers. Indeed, at the heart of Veja is its strength in developing and maintaining healthy relationships with the various farmers, factory workers, and related NGOs. According to Morillion: “People are often amazed by what we’ve managed to create, but we don’t do a lot, we just connect the dots between amazing projects to create a great sneaker.”[5]

Veja and its stakeholders are also motivated by allowing everyone to grow in their capacity and power. For example, Kopp and Morillion are happy to have reduced their involvement in the day-to-day management of the factory in Brazil, and in the management of its logistical operations in France. They also provide advice to new start-ups in eco-fashion. Their goal is not to become the next global giant but rather to motivate everyone to work toward enhancing socio-ecological well-being. Says Kopp:

We don’t want to be another Nike. We want to show if two friends with no background in this industry can do it, everybody can do it. We want Veja to be an example and we want to say to the other brands, with all the money you have, with all the knowledge you have, with all the power you have, you can do much more.[6]

Overall, Veja and its stakeholders have been motivated to make significant accomplishments. Says Kopp:

It’s possible to make a company with equilibrium where the boss or owners of the company are not paying themselves like crazy and [instead] everybody is well-paid, and the minimum salary is high and the maximum salary is low—and it’s cool; everybody can live a very happy life with that.[7]

Since opening, Veja has sold over 3 million sneakers—which are available in seventy countries from 3,000 retailers—and, to enhance its sustainable impact, has opened cobbler shops around the world to repair sneakers.

14.1. Introduction

Motivation is a psychological force that helps to explain what arouses, directs, and maintains human behavior. People who are highly motivated will persist in behaving in a certain way. There are two basic types of motivation. Extrinsic motivation refers to behavior that is exhibited because of the promise of some desired outcome (reward) from someone else, such as a supervisor or higher-level manager. Outcomes may be in the form of promotions, pay increases, time off, special assignments, office fixtures, awards, praise, and many other things that an individual desires. The focus in extrinsic motivation is on rewarding people who achieve goals, regardless of whether the goals or work activities are meaningful to the person accomplishing them. By contrast, intrinsic motivation refers to behavior that is exhibited because the task is inherently satisfying, enjoyable, or meaningful to the person. The source of motivation is the actual performance of the task. Some research suggests that if both extrinsic and intrinsic outcomes are present in a job or task, over time the extrinsic outcomes may come to dominate the intrinsic outcomes to the point that intrinsic motivation disappears.[8] For example, if a person loved playing hockey while growing up but then becomes a professional athlete and gets paid for playing, that person may lose some of their original intrinsic pleasure and begin to see playing hockey merely as a job.[9]

In this chapter, we look at why and how people are motivated to behave the way they do in organizations. The goal is to better understand (a) what prompts people to initiate actions; (b) how much effort they will exert; and (c) the extent to which their efforts persist over time.

Managers want members to be motivated to behave in ways that benefit the organization. Understanding and managing motivation can be challenging for a variety of reasons, including the fact that there may appear to be no direct relationship between a motivation and an action. The same action may result from many different motivations, and the same motivation may lead to different actions. Motivation is also challenging to manage because it can be seen as having two different sources—innate needs and personalities that people are born with, and acquired needs and desires that are shaped by people’s lived experiences. Using the computer as a metaphor, we can say that each person has unique hardware (a natural personality and innate needs that they were born with) and unique software (acquired needs and values that are shaped by childhood experiences, the country they live in, the social media they use, etc.). We will examine each of these basic types of needs and how they are managed in Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) organizations.

14.2. Innate Bases of Motivation

14.2.1. Personality

An individual’s personality (or disposition) is one factor that shapes what they are motivated to do.[10] Peoples’ personalities are rooted in their biological makeup much more than in their background or upbringing. This is illustrated by considering how members from one family can be very different despite a similar upbringing. One sibling may be very neat and organized, and another may be very sloppy and disorganized. One sibling may be talkative while another is shy. In short, people have different traits. Traits are personal characteristics that are relatively stable. Researchers describe personality traits as falling into five broad categories, called the Big Five:[11]

- Conscientiousness: achievement oriented, responsible, persevering, dependable.

- Agreeableness: good-natured, cooperative, trustful, caring, gentle, not jealous.

- Extraversion: sociable, talkative, assertive, adventurous.

- Emotional stability: calm, placid, poised, not anxious or insecure.

- Openness to experience: intellectual, original, imaginative, cultured, curious.

Management researchers have been especially interested in the relationship between the Big Five and individual behavior and performance.[12] For example, the personality trait of conscientiousness has been shown to be a good predictor of performance in most jobs, and extraversion is particularly helpful for predicting success in jobs with a great deal of social interaction. In a team or group context, conscientiousness and extraversion also contribute to team performance, and agreeableness helps the team bond, reduce conflict, and perform.[13] Research on the Big Five helps managers to explain behavior and to create selection instruments that enhance the fit between people and jobs by helping them to identify individuals who will be more naturally inclined or motivated to be productive when performing the tasks they are being hired for (e.g., extraverted people will be more naturally motivated to perform well in sales positions).

Beyond these basic job-related issues (which are typically emphasized in FBL and TBL organizations), in SET organizations members are also interested in how personality influences people’s motivation to work for social and ecological well-being. As with their effect on productivity generally, extraversion and conscientiousness also have a positive effect on social and ecological well-being. But the highest correlation is with openness, which does not have an effect on financial well-being. Agreeableness, again, has a positive effect on enhancing social well-being.[14] Put differently, people who are high on the traits of openness and agreeableness will be more naturally inclined or motivated to enhance social well-being (e.g., people with high openness are more naturally motivated to work with diverse others, which may put them in a better position to address complex socio-ecological problems).

A sixth personality trait that many researchers have recently been studying—honesty-humility—also has a positive effect on social and ecological well-being but is not associated with economic benefit.[15] People high in honesty-humility don’t cheat or manipulate others for self-serving purposes, and they lack a sense of entitlement and a desire for a lavish lifestyle.[16]

14.2.2. Innate Needs

In addition to the preferences that are rooted in an individual’s personality, people also have basic innate needs.[17] People obviously need to eat and sleep, but they also have inherent needs to relate to others and to make contributions or to create.

Abraham Maslow developed a well-known model of motivation that identified five human needs: (1) physiological (food, clothing, shelter); (2) safety (stability, protection from harm); (3) belongingness (love, meaningful relationships with others); (4) esteem (desire for recognition and respect); and (5) self-actualization (realizing one’s full potential).[18] Where Maslow got it wrong is in arranging these needs hierarchically, suggesting that lower-order (e.g., physiological) needs must be substantially satisfied before the motivational value of higher-order needs is activated.[19] For example, he suggested that people will not be motivated by their need for self-actualization if their need for belongingness is not met, and that they will not be motivated by their need for belongingness if their need for food and shelter have not been met. However, in reality everyone—even the billion or so people on the planet who do not have adequate food and shelter—is motivated by a need for belongingness and self-actualization.

A subsequent needs theory that enjoys much stronger research support is Clayton Alderfer’s existence-relatedness-growth (ERG) theory, which identifies three basic needs that are not hierarchically related.[20] These needs center on existence (physiological needs and safety), relatedness (belongingness),[21] and growth (esteem and self-actualization).[22] According to ERG theory, a desire to meet any or all of these needs can motivate someone’s behavior at any given time. Alderfer also introduced the frustration-regression principle, which suggests that people who are unable to satisfy some needs at a basic level will compensate by focusing on over-satisfying other needs. For example, a CEO who cannot fulfill a need for relatedness may direct their efforts toward making a lot of money.

Frederick Herzberg’s two-factor framework—which differentiates between (a) hygiene factors and (b) motivator factors[23]—may help managers to better understand how to manage each of the three ERG needs to enhance employee job satisfaction and motivation. Hygiene factors address issues of work context; they include factors such as working conditions, pay, company policies, and interpersonal relationships. By contrast, motivator factors address issues of work content; they include interesting work, autonomy, responsibility, being able to grow and develop on the job, and having a sense of accomplishment. According to Herzberg, whereas motivator factors can increase satisfaction, hygiene factors can simply reduce dissatisfaction; in other words, hygiene factors decrease demotivation but do not increase motivation. Although the two-factor model has its own shortcomings—many factors influence both dissatisfaction and satisfaction to some degree—Herzberg’s most prominent contribution was in challenging the prevailing assumption that pay is the most important motivator. According to his research, satisfying needs associated with growth and autonomy are more important motivator factors than pay.[24] Herzberg’s theory and findings continue to be contested, but managers can draw on his work to consider the influence of a variety of factors in motivating workers.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Innate Needs

All three approaches to management benefit from recognizing that people have ERG needs that they are motivated to satisfy. Managers should consider how to create work environments where employees’ motivation to meet their ERG needs also motivates them to perform their work. Similarly, all three approaches suggest that managers should consider how to make sure that employees work in an environment that provides adequate pay, safety, and respect (hygiene factors), though there are clear differences among the three approaches in how they understand the word “adequate.” For example, in the opening case, “adequate” for Veja means paying employees a living wage and giving them weekends off, whereas most of the world’s shoes are manufactured by people working for a minimum wage, often in deplorable working and living conditions.[25]

There are other important differences between SET and the other two management approaches. First, a SET perspective may be more inclined to see pay primarily as a hygiene factor (everyone needs enough, but more than enough does not increase motivation), whereas FBL and TBL approaches are more likely to see pay as a motivator factor in meeting relational needs (more money means more people will want to be your friend) and growth needs (more money means more self-esteem and self-actualization). Even though research suggests that money does not accomplish these things—that is, money does not buy happiness—the mantra of “more money is better” has proven difficult to resist for many.[26]

Second, a SET approach is more likely to challenge another assumption embedded in Maslow’s hierarchy, namely that self-actualization is at the apex of the hierarchy. In contrast, a SET perspective suggests that the apex might better be called community actualization. Recall from Chapters 1 and 5 that from a virtue theory perspective, true happiness cannot be achieved at the individual level of analysis (e.g., self-actualization); rather, it comes from practicing the four cardinal virtues in community. Put in terms of motivation, virtue theory essentially argues that people will be motivated to participate in and contribute to organizations where members practice and experience virtues like justice, courage, self-control, and practical wisdom.[27]

Third, whereas FBL and TBL approaches have a greater focus on motivator factors for individuals, a SET approach places greater emphasis on improving hygiene factors related to socio-ecological externalities, and on motivator factors that enhance a community. For example, contrary to FBL and TBL perspectives, a SET manager like Dan Price (Chapters 3 and 5) was motivated to reduce his $1 million salary in order to increase the salary of his employees (essentially to ensure that their pay is enough, a hygiene factor). He is motivated to work hard to ensure that Gravity Payments is able to maintain such community-building practices.

Test Your Knowledge

14.3. Acquired Bases of Motivation

In addition to being born with certain personality traits and innate needs, over their lifetimes people also acquire certain needs. These acquired needs are shaped by factors like the national values of the countries where they live, the norms and practices of organizations they work for, and by the values and lifestyles of their family and friends. We will look at four particularly important acquired needs, namely the needs for accomplishment, fairness, relationships, and power.[28]

As might be expected, there is some overlap between people’s innate needs and their acquired needs, such as the needs for relatedness and relationships. However, their acquired needs for affiliation and community, power, and fairness will be shaped by the different cultures and contexts they live in. These acquired needs (which we will sometimes call “desires” to differentiate them from innate needs) are especially important for managing motivation, because they can be further changed and shaped in the workplace. In addition to overlapping with innate needs, the four acquired needs we will discuss are also related to the three elements of social well-being described in Chapter 5: meaningful work is related to satisfying needs for accomplishment and for power; belongingness is related to satisfying the need for relationships; and peace and justice are related to satisfying need for fairness.

We will look at each of the four acquired needs in turn, describe different theories that explain how they can be used to motivate people, and discuss differences between the FBL/TBL and SET approaches.

14.3.1. Desire for Accomplishment

Of the four main acquired needs discussed in the motivation literature, the desire for accomplishment (or achievement) has received the most research attention. The desire for accomplishment is relevant for each of the three approaches to management, but we can expect there to be differences on what sort of accomplishment is desired. For example, an FBL/TBL approach focuses on how the desire to achieve productivity and financial performance-related goals can be very motivational. A SET approach considers how accomplishing significant socio-ecological goals can be motivating.

These two types of accomplishment are evident in the career of Elizabeth Lee, who managed thousands of people as Chief Operating Officer for UMC-Nissan and had an impressive list of other achievements, including being the first female chairperson of the Chamber of Automotive Manufacturers of the Philippines Inc. She left all of that in order to found EMotors Inc., which manufactures ZüM electric trikes that promise to provide increased opportunities for low-income microentrepreneurs (social well-being) and to reduce noise and greenhouse gas pollution (ecological well-being). For Lee, success is not about making as much money as possible but about having a positive impact on others and on the environment.[29]

Accomplishment and Goal-Setting Theory

Goal-setting theory is one of the most studied and supported of all management theories. There are at least two reasons why goal setting can have positive outcomes. First, engaging in the planning process and setting goals encourages careful thought to what should be accomplished. In other words, goal setting is effective at pointing to what should be done. Second, setting goals motivates people to work. In other words, people get satisfaction from achieving a goal that meets their acquired need for accomplishment.[30]

Recall that research shows that SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, results based, and time specific) lead to increased productivity.[31] SMART goals are motivational because of people’s desire for achievement. SMART goals increase performance gains more than a goal like “do your best.” This knowledge has been used to great effect by FBL/TBL managers to optimize their employees’ productivity.

Recall also that a SET approach is somewhat different.[32] Instead of appealing to people’s motivation to accomplish any goal, SET management appeals to people’s motivation to accomplish goals that are significant, meaningful, agreed upon, relevant, and timely (SMART 2.0 goals). For example, from a SET perspective as informed by virtue ethics, using money to make more than enough money would not be a motivating goal (and in fact, it may be a demotivating goal). Rather, goals that are aligned with providing goods and services that nurture overall well-being are motivating because they allow people to meet their desire for significance. Goals like “do your best” may not maximize productivity, but they may motivate people to become more collaborative, improve relationships between leaders and followers, and result in reduced negative self-evaluations and stress.[33]

Accomplishment and Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory provides a closer look at key factors in the motivation link between setting goals and the desire for accomplishment.[34] In particular, expectancy theory describes how motivation can be increased by increasing employees’ expectations that they can achieve certain goals, and that the achievement of those goals will be linked to rewards that they value. As depicted in Figure 14.1, motivation is considered a function of three separate thought calculations, regarding expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

Figure 14.1. An individual-focused variation of expectancy theory

Expectancy refers to the probability perceived by an individual that exerting a given amount of effort will lead to a certain level of performance (“Can I achieve the goal?”). Research shows that the greater the confidence employees have that their efforts will produce desired outcomes, the greater will be their motivation. Confidence is a critical component for a number of theories of motivation. Expectancy is related to self-efficacy.[35] Recall from Chapter 6 that self-efficacy refers to a person’s belief that they are able to complete a task successfully.[36] A person’s self-efficacy can be increased by coaching, training, providing ample resources, conveying clear expectations, and other factors under the control of managers. One interesting example, discussed in Chapter 2, relates to research supporting self-fulfilling prophecies, which shows that subordinates often live up (or down) to the expectations of their managers.[37] In other words, a simple word of encouragement—such as saying “I believe you can do it”—can go a long way toward building someone’s confidence and expectancy. High expectancy contributes to high levels of effort and persistence. High levels of expectancy are likely when someone has the appropriate amount of capability, experience, and resources (e.g., time, machinery, tools). A student may be motivated to earn an A in a class if she believes that with hard work it is possible. However, if the student believes earning an A is not possible given her limited capability or available time to study, she will have low expectancy.

Instrumentality refers to the perceived probability that successfully performing to a certain level will result in attaining a desired outcome (“Will I get something for achieving the goal?”). Employees are more likely to be highly motivated if they think that their high performance will serve as means to certain ends (outcomes) such as pay, job security, interesting job assignments, bonuses, or feelings of achievement. A student may be motivated to earn an A in a class if he believes that the A grade will be instrumental in gaining entrance to a professional program or securing a job. If an A is not perceived to be linked to any foreseeable valued outcome, his motivation is likely to be low.

Valence is the value an individual attaches to an outcome. To motivate organizational members, a manager needs to determine which outcomes (or rewards) have high valence for each member (i.e., which rewards are highly valued) and make sure that those outcomes are provided when each member performs at high levels. Simply put, the higher the value of the outcome to the employee, the greater the motivation. Returning to the student example, the more the student values the outcome of entrance to a professional program (“I’ve always wanted to be a lawyer”), the more motivated he might be. On the other hand, if being a lawyer was Mom’s or Dad’s dream for the student and not his own, it is not likely to be as motivating.

A sales department example can be used to explain how all three elements work together. If a salesperson at a diamond jewelry shop has learned that increased selling effort will lead to higher personal sales, expectancy is high. Additionally, if the salesperson believes that higher sales will lead to a promotion or a pay raise, instrumentality is high. Lastly, if the salesperson places a high value on the promotion or pay raise, valence is high. Such a salesperson would be highly motivated. On the other hand, if expectancy, instrumentality, or valence is low, motivation may be low. This theory is very practical; managers can take action to make sure that employees believe they can achieve goals, that the goals are linked to clear outcomes, and that the outcomes are valued by employees. Research supports the idea that expectancy, instrumentality, and valence each have an effect on motivation.[38]

Consistent with Figure 14.1, expectancy theory has typically been discussed with regard to individual employees, which fits with a traditional FBL approach that emphasizes individual self-interests (Chapter 1). However, expectancy can also be applied at a group or community level of analysis, which is more in keeping with a SET perspective. A group-level application can also be used within the FBL approach, but FBL managers would be more interested in goals like maximizing corporate profits, whereas SET goals would be more likely to include optimizing socio-ecological goals.

As shown in Figure 14.2, a variation of expectancy theory that places less emphasis on individuals replaces an “I can do it” view of expectancy with “We can do it.” The difference may appear subtle, but the implications for managing motivation can be profound. First, instead of primarily focusing on and building self-efficacy, a SET approach would seek to pursue goals in the context of community and in building group efficacy. Group efficacy refers to group members’ belief that they are able to complete a task successfully. Groups with high levels of expectancy not only perform well over time, but their members also are likely to be motivated by group processes such as participative decision-making, cooperative problem solving, and workload sharing.[39]

Figure 14.2. A community-focused variation of expectancy theory

Second, with regard to instrumentality, rather than considering “What’s in it for me?” the SET approach might ask, “What are the effects on others, especially those at the margins of society?” Elizabeth Lee, CEO of EMotors, notes that future leaders “will have to think of ‘What’s in it for we?’ instead of ‘What’s in it for me?’”[40] In other words, how is this goal related to employees’ desires for significance? Such a focus on community can be in tension with a focus on individuals. For example, research shows that the more people are given and rewarded based on measured individual goals, the less effort or attention is directed toward organizational citizenship behavior.[41] Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) means going above and beyond normal, required practices in order to serve organizational stakeholders.[42] By raising the question of “What’s in it for others?” and encouraging more collective thinking, a community focus encourages OCB.[43] The SET approach motivates organizational members through appealing to significant benefits others receive from members’ actions. Serving others is motivating and is related to unity with others, and consistent with a SET understanding of meaningful work and a meaningful life.[44] Lee says: “The key to happiness is not having things for yourself, the key to happiness is helping somebody else.”[45] The people you help may be co-workers, or they could be stakeholders who haven’t been born yet.

Finally, with regard to valence, a SET approach holds a less individualistic and less materialistic understanding of what is valuable. A SET approach may emphasize outcomes related to enhanced socio-ecological externalities (e.g., healthier living conditions, more choice in the workplace). In particular, a SET approach to motivation is more likely to recognize that people are motivated by more than simply money. Indeed, while it is important to earn enough money, recall that too much attention to financial rewards can reduce peoples’ intrinsic motivation. This brings us to reinforcement theory.

Accomplishment and Reinforcement Theory

Reinforcement theory provides a closer look at factors related to valence as described in expectancy theory. In other words, rather than look at how to manage goals, reinforcement theory focuses on how to manage the rewards linked to meeting goals. Reinforcement theory explains how to motivate employees to change their on-the-job behavior through the appropriate use of rewards and punishments. According to reinforcement theory, which generally focuses on extrinsic motivation, human motivation and behavior are determined by the external environment and the consequences it holds for the individual. Another term describing this process is behavior modification, a set of techniques by which reinforcement theory is used to modify human motivation and behavior.[46] The goal of behavior modification is to use reinforcement principles to systematically motivate desirable work behavior and discourage undesirable work behavior. There are four basic types of reinforcement, which provide a range of options that managers can choose among, depending on the situation and the costs involved.

(i) Positive reinforcement is the administration of a pleasant and rewarding consequence following a desired behavior. For example, when a manager observes an employee doing an especially good job and offers praise, this positive response reinforces the behavior and increases the likelihood it will occur again in the future. It also satisfies the individual’s desire for accomplishment. Other positive reinforcers include pay raises, promotions, and most anything that people regard as a desirable consequence. For managers, positive reinforcement is the preferred approach for increasing desirable behavior and increasing learning. Of course, a reinforcer is only positive if it is something that is valued by the person who receives the reinforcement. For example, tickets to an NBA basketball game might be a positive reinforcer for some people but not for others.

(ii) Punishment refers to the application of an unpleasant consequence after an undesirable behavior has occurred. For example, a supervisor may berate an employee for performing a task incorrectly, or a professor may take off points for a late student assignment. The supervisor and professor expect that the negative outcome will reduce the likelihood of the unwanted behavior recurring in the future.

(iii) Negative reinforcement is the removal of an unpleasant consequence following a desired behavior.[47] This type of reinforcement is based on the idea that employees will exhibit the right behaviors in order to avoid unpleasant outcomes. Negative reinforcement is evident when a student comes to class on time in order to avoid a disapproving look from the professor, or when an employee completes work before a deadline in order to avoid a reprimand from a boss. Note the difference between negative reinforcement and punishment: the latter reduces the likelihood of future unwanted behavior, while the former increases the likelihood of future desired behavior.

(iv) Omission is the absence of any reinforcement, positive or negative, following the occurrence of a behavior. It can be used to weaken an unwanted behavior, especially a behavior that has previously been rewarded. The idea is that a behavior that is not positively reinforced will be less likely to occur in the future. For example, suppose an employee wastes everyone’s time by telling them interesting stories (which results in a lot of attention being paid to the employee). In order to extinguish this behavior, a manager might counsel co-workers to stop paying attention to the employee’s stories. The reduced attention the employee receives will reduce the likelihood of such storytelling behavior in the future.

These four basic types of reinforcement can be administered using different schedules of reinforcement. At the most general level, schedules are either continuous (a reward or punishment follows each time a behavior of interest occurs) or intermittent (the behavior of interest is rewarded or punished only some of the time). Continuous schedules rapidly increase desired behavior or decrease undesirable behavior, but learning is more enduring with intermittent schedules.

Reinforcement theory is usually discussed in terms of motivating employees to adopt behaviors that managers want, to help employees achieve certain rewards that they desire, and to increase their felt level of achievement. This is quite consistent with FBL/TBL management, but reinforcement can also be used to address the significance concerns that SET managers have.

While an FBL/TBL approach focuses on an individual’s self-interest, a SET approach takes a more holistic perspective, going beyond individuals and beyond extrinsic motivators. For example, instead of reinforcing a job well done by giving the employee a pay raise, a SET approach may reinforce a job well done with opportunities for them to spend a day helping out in a local soup kitchen on company time, or by showing them a sample of heartfelt thank-you cards from customers.[48] Of course, FBL/TBL managers also use non-financial reinforcements, but a SET approach places a greater emphasis on reinforcers that appeal to significance beyond the self-interests of individuals.

A SET approach may deliberately seek reinforcers that are intrinsically motivating and/or draw attention to the inherent significance of peoples’ jobs (although FBL and TBL management would also promote the use of such reinforcers if they were less expensive than providing financial reinforcers). Recall that if both extrinsic and intrinsic outcomes are present in a job or task, eventually the extrinsic outcomes may come to dominate the intrinsic outcomes, sometimes to the point that intrinsic motivation disappears.[49] By focusing on intrinsic reinforcers (e.g., how profits from sales of a particular product could be donated to a local charity, how a successful product launch created jobs that pay a living wage for a supplier in a low-income country, how reduced pollution results in a local river that is again fit for people to swim in), a SET approach seeks to counteract the fact an emphasis on extrinsic reinforcements can overtake people’s desire to meet intrinsically significant goals. This is consistent with research that says that an emphasis on materialism (e.g., extrinsic goals) reduces peoples’ overall quality of life and happiness,[50] and also reduces ecological well-being.[51]

Test Your Knowledge

14.3.2. Desire for Fairness

We all have some inherent sense of fairness that influences our thinking about our interactions with others.[52] What does the idea of fairness mean to you? People’s understanding of and desire for fairness can go in at least two directions. The first direction emphasizes people being treated equitably, which means getting the results they deserve for the effort they put forward when compared with others. In particular, individuals with a high desire for equity are motivated to ensure that they get treated fairly.[53] The second direction emphasizes ensuring that everyone be treated justly, including advocating for people whose best efforts are not rewarded with a living wage. Recall that the virtue of justice is evident when managers ensure that all stakeholders associated with a product or service receive their due and are treated fairly (being especially sensitive to fair treatment of the marginalized).[54] The discussion below will reflect on both of these understandings of fairness.

Equity Theory

Equity theory is based on the logic of social comparisons and the idea that people are motivated to seek and preserve social equity in the rewards they expect for performance.[55] Equity theory pays particular attention to the outcomes someone receives for their contributions compared to others in the workplace. For example, workers who feel underpaid compared to their co-workers are likely to be demotivated because of a perceived lack of fairness.

Perceived inequity has been shown to relate to decreased performance,[56] and to increased turnover and absenteeism.[57] According to the theory, people evaluate equity by observing the ratio of their level of input into their jobs (e.g., effort, ability, experience, and education) relative to the outcomes they receive from their jobs (e.g., pay, status, benefits, and promotions). This input-outcome ratio may be compared to that of another person in the workgroup or to a perceived group average.

The basic question associated with equity theory—“In comparison with others, how fairly am I being compensated for the work that I do?”—can be answered in three ways. First, someone may feel equitably rewarded if, for example, they feel that they are being paid fairly compared to their co-workers. This situation may occur even though the other co-workers’ compensation is greater, provided that those other persons’ inputs are also proportionately higher. Suppose one employee has a high school education and earns $40,000. He may still feel equitably treated relative to another employee, who earns $55,000 because she has a college degree.

Second, an employee may feel under-rewarded when, for example, they have a high level of education or experience but receive the same salary as a new, less-educated employee. Equity theory predicts that when individuals perceive that they are being under-rewarded and therefore treated unfairly in comparison to others, they will be motivated to act in ways that reduce the perceived inequity. Employees may try to deal with negative inequity by changing their own input-output ratio, changing the input-output ratio of their comparison person, or by changing their own and others’ ratios simultaneously in the following ways:

- putting less effort into their jobs and thereby lowering inputs (changing one’s own ratio);

- asking for a pay raise or some other higher outcome (changing one’s own ratio);

- pressuring others to provide more inputs (changing others’ ratio);

- attempting to limit or reduce others’ outcomes (changing others’ ratio);

- some combination of the above; or

- changing the situation by leaving their job.

It is not unusual for employees to leave an organization as a result of being lured by higher salaries elsewhere, only to return when they realize that the working conditions in the new company are harsher. This is illustrated by a comment from management at a busing company: “In the past we’ve had drivers leaving, but then they come back after realising the grass isn’t greener the other side.”[58]

Lastly, an individual may feel over-rewarded relative to others. Facing this situation, people will often rationalize the situation as appropriate. For example, an employee with a long history in the firm may justify her higher salary because of the historical knowledge she brings to decisions, whereas a new employee may justify his higher salary because he brings new ideas to the firm. However, if individuals do not rationalize their being over-rewarded, then equity theory suggests they will be motivated to reduce the over-compensation by increasing their inputs (by exerting more effort) or by reducing their outcomes (e.g., by taking a voluntary pay cut). When Mark Wahlberg was paid $1.5 million more for doing the same work on a movie as Michelle Williams, he donated the extra money to the #TimesUp legal fund related to the #MeToo movement.[59]

Equity theory applies to all three approaches to management described in this book (FBL, TBL, and SET). But managers in SET organizations typically interpret equity not simply in terms of people’s desire for traditional rewards for their contributions but also in terms of concern for others. From the SET perspective the question is not so much “Am I getting my fair share?” as it is “What can I do to help those stakeholders who are not getting their fair share?” This different understanding of equity is closer to the understanding of justice described earlier, which is a hallmark of the virtue ethics that the SET approach is built upon.

This emphasis on overall justice is evident when organizational members are asked to develop the distribution rules that will determine how much everyone is paid for the input they provide. Research suggests that when people are allowed to participate in the development of distribution rules that they perceive to be fair, the rules tend to take into account both the innate needs of members (e.g., the poorest-performing members should not be relegated to poverty, everyone should earn a living wage) and their performance (e.g., highly productive people should be paid more). In such an organization everyone may have a base salary that pays a living wage, and then earn pay increases based on their relative productivity. Research also suggests that people who develop and work under such two-pronged decision rules (where fairness is based on both need and productivity) tend to be more motivated than people who work under equity rules based only on productivity or only on need.[60] Thus, motivation is optimized with a combination of (a) ensuring that no one is mistreated (SET approach); and (b) ensuring that everyone gets their fair share based on their performance (FBL approach). This is how the system operates at Veja sneakers, as described in this chapter’s opening case.

Test Your Knowledge

14.3.3. Desire for Relationships

People have an innate need for interpersonal relationships, and this innate need is elaborated further by the acquired need for relationships that develops based on culture, family, and other life experiences. Chapter 5 summarizes the research on interpersonal relationships in the workplace and notes differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches. In the FBL/TBL literature on motivation, the acquired need for relationships is usually referred to as the desire for affiliation, while in the SET approach the emphasis is more on the desire for community.

At the organizational level of analysis, managers can harness the motivational potential of people’s desire for relationships by fostering organizational commitment, which is a motivational force that binds a person to a particular organization.[61] Employees who are emotionally attached or committed to an organization are motivated to contribute positively to it by willingly exerting effort, helping others, and making creative contributions.[62] Commitment—which can reduce turnover costs and increase group productivity—can often be implemented in relatively simple ways such as hosting picnics, sponsoring softball teams, and providing a fun environment in which to work.

At the interpersonal level of analysis, a common way to think about workplace affiliation is via the lens of exchange theory, which examines the give-and-take of relationships.[63] Research suggests that there are three kinds of people in organizations: givers (people who contribute time and effort to others without seeking anything in return), takers (people who get help from others while guarding their own time and expertise), and matchers (people who seek to balance giving and taking).[64]

When we assume that people are self-interested—as is emphasized in the FBL approach—it makes sense that they will be attracted to relationships where the benefits they receive are at least equal to the time and energy they invest.[65] Moreover, from such an exchange perspective, people will seek interpersonal relationships that offer instrumental value. In a world where “taking” seems to be the smart way to get ahead, the following observation from Bill Gates sounds odd:

There are two great forces of human nature—self-interest [takers], and caring for others [givers]. In many organizations, those forces come together with damaging effect. With thoughtful management, however, they can be yoked in such a way that caring for others [giving] becomes the best strategy for the most ambitious.[66]

It turns out that research supports Gates’s contention. Studies show that the top-performing employees in organizations are more likely to be givers than takers. But the opposite is also true: low-performing employees are also more likely to be givers (because they are taken advantage of by others). These findings suggest the importance of developing a better understanding of how to be a giver without being taken advantage of by others.

The hallmarks of best practices for givers may be more consistent with a SET approach than with an FBL approach. For example, research suggests that givers excel when they assertively and compassionately seek to promote and serve the interests of other stakeholders who have little power. Whereas givers are often not good at (or interested in) maximizing their own salaries, they are often good at arguing on behalf of others.[67] At the same time, it is better for givers to act with compassion (i.e., support others who are suffering) than be overcome by empathy (feeling the pain of others who are suffering). Research suggests that empathetic givers may be more vulnerable to being manipulated, can get too emotionally involved (which can burn them out), and may create unhealthy dependencies for the people they are trying to help.[68]

Finally, recall that a SET approach to relationships extends beyond simple exchanges and includes building a sense of community and serving others and treating them with dignity.[69] Moreover, relationships with other people are motivating not only because we need to receive love and affirmation but also because we need to give love and affirmation and make sacrifices for others. As illustrated in the Veja case, it is inherently motivating to belong to a community and to use your gifts, time, and resources to serve others.

14.3.4. Desire for Power

Power has been defined in many different ways. As we use the term, power refers to the potential that one person has to influence and control someone else’s behavior or to change the course of events.[70] This definition recognizes the fact that some people have power but never use it, and that someone who is perceived to be powerful but fails to achieve the control they desire is actually not as powerful as previously thought. For example, only time will tell whether Elon Musk has the power to change the automobile industry and to get humans to Mars (see Chapter 15, opening case).

People’s desire for power has an effect on motivation in at least two ways. First, people may be motivated to seek power. Research suggests that takers and givers understand power in different ways. Takers are more likely to view power as an opportunity to meet their own goals of having control over others, whereas givers are more likely to see power as a responsibility that demands taking into account the effect their actions will have on the well-being of other stakeholders (see servant leadership, Chapter 15).[71] Matchers might seek power for a combination of these two reasons.[72] Second, people can use their power to motivate others. Indeed, a focus in this textbook is on how managers can use their power to motivate various organizational stakeholders. FBL/TBL managers typically use their power to maximize profits, while SET managers are more likely to use it to optimize socio-ecological well-being.

In order to better understand how power is acquired and used by FBL, TBL, and SET managers, it is helpful to understand the different sources of power and how power is shared differently in organizations managed according to FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

Sources of Individual Power

At least five sources or types of individual power have been identified, three of which are related to someone’s formal position in an organization—legitimate, reward, and coercive power—and two of which are related to personal factors—expert and referent power.[73]

Legitimate power is the capacity of someone to influence other people by virtue of one’s position in an organization’s hierarchy of authority. Legitimate power is synonymous with formal authority. It enables managers to set the agenda for their work unit, to make decisions, and to develop and implement strategies. A person with legitimate power has the authority to say, “Because I am the boss, you must do as I ask.” Most employees comply with the requests of those with legitimate power. When a person holds legitimate power, it is common for them to also have reward and coercive power. However, a person can have reward or coercive power without legitimate power.

Reward power is the ability to influence the behavior of others by giving or withholding positive benefits or rewards. These can be tangible rewards as in pay raises, bonuses, or choice job assignments, or intangible rewards such as verbal praise, a pat on the back, or a show of respect. A reward can be anything that one person has access to and can give that is valued by another person. A person who uses reward power implicitly says, “If you do what I ask, I’ll give you a reward.” The opposite side of the coin of reward power is coercive power, which refers to someone’s ability to influence the behavior of others through the threat of punishment. This includes the capacity to ensure compliance through psychological, emotional, and/or physical threat. Today, for the most part, coercive actions are limited to verbal and written reprimands, disciplinary layoffs, fines, demotion, and termination.

Building on our earlier discussion of reinforcement theory, the use of legitimate, reward, and coercive power is likely to motivate others’ immediate compliance, but it may not motivate ongoing commitment.[74] For example, employees may (unenthusiastically) obey orders and carry out instructions in the short term even though they may personally disagree with them. If these sources of power are overused, they may lead to resistance and demotivation among employees.

In contrast, expert and referent power are more likely to motivate employees to higher levels of commitment. Expert power is the ability to influence the behavior of others based on special knowledge, skills, and expertise that one possesses. While everyone may value being appreciated by others, people with a desire for power may be especially motivated to take advantage of the power that comes with their recognized expertise. When a person has a great deal of technical know-how or information pertinent to the task at hand, others will often be motivated to go along with the recommendations because of that person’s superior knowledge. To develop expert power, one must acquire relevant skills or competencies, or gain a central position in relevant information networks.

Finally, referent power is the ability to influence the behavior of others on account of their loyalty to or desire to imitate or identify with the power holder. Because others are attracted to the person who holds power and want to be like that person, they are more likely to do what the person requests. Referent power is more informal and abstract than the other kinds of individual power. It transcends any formal title or position in an organization and is a part of transformational leadership that is described in Chapter 15.

Sharing Power

Sharing power with employees by consulting with them and seeking their input increases their motivation levels.[75] In some organizations—like worker-owned cooperatives or kibbutzes—the very structure of the organization ensures that everyone has a share of the power. In other cases, power may be shared on a more piecemeal basis, such as when a manager empowers workers to participate in making certain decisions or delegates specific decisions to them.

In environments with high levels of shared power, people are motivated to spot problems, solve problems, engage clients, and satisfy clients because they “own” the work. Organizational members who see themselves as empowered are generally more innovative, less resistant to change, more satisfied, less stressed, and judged as more effective by others.[76] Empowered people also have a stronger bond with the organization, confidence in their abilities, and a clear sense of being able to make a difference.[77] When employees have meaningful participation in goal setting, they are more committed to achieving the goal that has been set.[78]

For example, the QuikTrip convenience store chain has been ranked on Fortune’s list of the “100 Best Companies to Work For.” Why? Consistent with its long-standing desire to have every employee grow and succeed,[79] 87 percent of QuikTrip employees have said: “Management trusts us to do a good job without watching over our shoulders,”[80] and “This company makes everyone feel important.”[81] In essence, QuikTrip recognizes that collectively, members have the expert power necessary to run the store, so the firm pays frontline workers more than they expect.[82] In contrast to this example, managers who seek to gain and hold power create a sense of powerlessness and helplessness that demoralizes employees. Consider how frustrating it is to know how to solve a problem but not be given the opportunity to do so.

FBL, TBL, and SET approaches recognize the same sources of power and similar benefits to sharing power. However, as we have already discussed, FBL and TBL managers are more likely to be motivated to seek power as an opportunity to serve their own interests and to get ahead, whereas SET managers are reluctant to seek power for their own interests but are motivated to seek it to fulfill their responsibility to other stakeholders. Thus, there are differences not only in the desire for power but also in the use of power.

Similarly, although all three approaches recognize the benefits of sharing power, the nature of those benefits differ. From an FBL perspective, power sharing makes sense only when it results in overall performance gains that serve the organization’s financial well-being. While also welcoming such performance gains, the SET approach also promotes empowering people who have the expertise to make decisions because it the right thing to do.[83]

One of the more intriguing ideas from a SET perspective is that power is not the zero-sum game that it is often assumed to be in FBL/TBL approaches. An FBL/TBL approach typically assumes there is a limited amount of power within an organizational work unit. For example, if a manager empowers a follower to make a decision, that manager loses some amount of power (say, X units) and the follower gains the same amount of power (also X) units. Because the loss of the manager’s power and the gain of the follower’s power is the same, it is a zero-sum transaction (X X 0).

In contrast, a SET approach argues that when a manager gives power to others, the overall amount of perceived power in the work unit increases. By empowering others, a manager may gain referent power from increased admiration on the part of followers, or gain expert power if followers interpret empowerment as a sign of an especially skilled or knowledgeable manager. Imagine a fast-food franchise where the manager retains all the decision-making power and schedules everyone’s hours, versus a neighboring franchise where the manager empowers staff to make some of those decisions. Research suggests that in the latter organization, everyone will perceive themselves to have more power than in the former organization, and the latter organization may well outperform the former.[84] Maybe power is a bit like love: the more you horde it for yourself, the less there is; and the more you share it with others, the more there is for them and for you.[85]

Test Your Knowledge

14.4. Entrepreneurial Motivation

What motivates some people to become entrepreneurs, but not others? Chapter 1 identifies the three most common reasons entrepreneurs give for founding their organizations: the desire for more freedom and autonomy; the desire to address an important problem; or the desire to gain wealth and power. But most people want at least one of these things, so desiring them does not help to distinguish entrepreneurs from non-entrepreneurs. Similarly, almost everyone has complaints about some product or service that they use and ideas about how it could be improved. Therefore, virtually everyone has had ideas that could potentially be pursued as an entrepreneurial venture.

But most people don’t actually become entrepreneurs. What motivates entrepreneurs to actually take action? Research suggests that for an individual to start and manage a new organization typically requires both psychological and environmental sources of motivation, though both may not be equally important at all stages of the start-up process.[86] It seems that entrepreneurs’ decisions to take action depends on who they are, but the situation in which they operate determines their level of success.

14.4.1. Psychological Sources of Motivation

Researchers have found that entrepreneurs differ from the general population in at least two ways.[87] First, individuals who found businesses have a more internal locus of control. Locus of control is a person’s beliefs about the sources of success and failure. A person with an internal locus of control believes that they are masters of their own fate and that their actions can shape their environment. In contrast, people with an external locus of control feel that things simply happen to them and that they are at the mercy of their environment. Entrepreneurs tend to believe that the success or failure of their organization is related to their own actions, not to luck or the actions of others. Second, entrepreneurs also tend to have a higher-than-average need for accomplishment, and entrepreneurs with the greatest need for achievement tend to be the most successful. Taken together, these two differences suggest that entrepreneurs are especially motivated by the ability to influence the world around them and create something new and excellent.[88]

There are other areas where entrepreneurs don’t seem to be much different than non-entrepreneurs. For example, despite what many people assume, founders of new organizations are not consistently more risk-tolerant than other people.[89] It is also true that the personalities and motivations of senior managers are very similar to those of entrepreneurs. While entrepreneurs have a higher need for achievement than most of the population, so do senior managers. It seems that success in management requires and rewards the same qualities that motivate entrepreneurs (this is consistent with the view that entrepreneurship is fundamentally a management activity).

14.4.2. Environmental Sources of Motivation

External motivation comes from factors in the environment where the entrepreneur lives and works, either by “pushing” or by “pulling” individuals to start a new organization. Overall, there are more opportunity-driven entrepreneurs (pull) than there are necessity-based ones (push), though as you might expect, the frequency of each type depends on the local environment.[90]

People facing difficult situations can be pushed to become an entrepreneur even if they would prefer to not be one. For whatever reason, if an individual cannot find appropriate work in an existing organization, their only option may be to create an organization of their own. Such necessity-based start-ups tend to be more common in countries and regions with greater wealth disparity and fewer opportunities for the disadvantaged.[91] Any situation that presents systemic barriers (such as racism) tends to make necessity-based entrepreneurship more important.[92]

In contrast, people can be pulled to become entrepreneurs because of enticing opportunities in the environment to work more independently. Entrepreneurs motivated by pull factors tend to be more common and more successful.[93] All of the environmental factors that are important in managing an existing organization are also important for understanding the motivation to start a new organization. For example, political and legal institutions can be important sources of motivation (e.g., government support for start-ups through a well-functioning regulatory system). Similarly, the forces that make a market more or less attractive to corporate strategy (e.g., barriers to entry, level of competition) also influence how much motivation entrepreneurs will have to start a new organization, as will the characteristics of the organizational environment, including stability and available technology.

14.4.3. Differences Between FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Entrepreneurial Motivation

Regardless of their management approach—FBL, TBL, or SET—all entrepreneurs can be motivated by psychological factors and environmental push-and-pull forces. However, these factors will differ in expected ways. For example, FBL/TBL entrepreneurs will be more likely to have a need to achieve financial goals, whereas SET entrepreneurs will be more likely to have a need to accomplish socio-ecological goals (e.g., Veja sneakers). Similarly, FBL entrepreneurs will be more likely to be pushed or pulled to enhance their own well-being, whereas SET entrepreneurs are more likely to be pushed or pulled to enhance the well-being of others. For example, when Elizabeth Lee founded EMotors she did not need more money or freedom for herself—she already had those in a high-paying and challenging job in the regular auto industry. Rather, she was pulled in by a desire to make the world a better place, thanks in part to an earlier project she had worked on with her mother to help poor people in her country, which showed her the need for an electric vehicle.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- To understand motivation, managers must be aware of people’s personality traits, innate needs, and acquired needs. How motivation is managed differs between an FBL/TBL perspective and a SET perspective.

- With regard to the Big Five personality traits (emotional stability, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness):

- An FBL/TBL approach focuses on the relationship between traits and performance (e.g., conscientiousness is generally positive, extraversion is positive for jobs requiring social interaction, agreeableness is positive for teamwork).

- A SET approach adds other traits that are associated with being motivated to enhance socio-ecological well-being (e.g., openness, honesty-humility).

- With regard to the innate needs of existence, relatedness, and growth:

- An FBL/TBL approach is more likely to focus on the individual level of analysis, and more likely to view pay as a motivator factor (“more money is better”).

- A SET approach is more likely to focus on the community level of analysis, and more likely to view pay as a hygiene factor (“everyone needs enough money”).

- With regard to the acquired need for accomplishment:

- An FBL/TBL approach emphasizes achievement and focuses on developing SMART goals, enhancing self-efficacy and instrumentality, and deploying appropriate reinforcements and schedules that serve as extrinsic motivators.

- A SET approach emphasizes significance and focuses on developing SMART 2.0 goals, enhancing group efficacy and instrumentality, and deploying appropriate reinforcements and schedules that serve as intrinsic motivators.

- With regard to the acquired need for fairness:

- An FBL/TBL approach emphasizes the equitable treatment of each individual employee.

- A SET approach emphasizes the just treatment of each stakeholder.

- With regard to the acquired need for relationships:

- An FBL/TBL approach emphasizes affiliation and uses an exchange-based give-and-take lens.

- A SET approach emphasizes community building and values healthy giving relationships.

- With regard to the acquired need for power:

- An FBL/TBL approach emphasizes individual power and opportunities to get ahead.

- A SET approach emphasizes shared power and responsibilities to include stakeholders.

- Compared to non-entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs are more likely to have an internal locus of control, a higher need for accomplishment, and tend to be pushed and/or pulled into forming a start-up organization.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Consider for a moment your motivation to do well as a student. Do you desire to achieve good grades so you can get a well-paying job? Or are you motivated by a desire for a more significant and meaningful understanding of management, which you can use to live a more fulfilling life?

- What happens when there is an overemphasis on extrinsic motivators like pay or good grades? What are the implications for management practice?

- How does your personality affect your motivation? List some things you naturally like to do. Is there an underlying pattern in these activities that hints at a particular aspect of your personality? Does it hint what sort of career path you should consider?

- Goal setting is well established as a means to improve motivation. What is your experience with setting goals in the workplace and/or in your personal life? When did it work (or not work) well?

- Discuss why two people with similar abilities may have very different expectancies for performing at a high level. What can you do as a manager to increase workers’ expectancies?

- You may have heard a few teachers complain that their pay is poor, yet they continue to teach. How can this be explained by motivation theory?

- What is your understanding of the difference between achievement and significance? Which do you find more motivating?

- Compare and contrast the equity view of the need for fairness versus the justice view. Which do you subscribe to? What factors have shaped your views?

- Describe the differences between the affiliation and community-building views of the need for relationships. Do you think one is better than the other? Explain your reasoning.

- Many managers have been accused of abusing their power in organizations. How can you make use of power without abusing it?

- Identify and describe any push-and-pull factors in your own life that may influence your choice to become an entrepreneur. Based on this chapter, do you think you have the personality traits associated with typical entrepreneurs? Does that influence your decision as to whether to become an entrepreneur? Explain.

- This case is developed based on a variety of sources, including Segran, E. (2024, April 9). Vega wants to report your sneakers—and train a new generation of cobblers. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/91088733/veja-wants-you-to-repair-your-sneakers-and-to-train-a-new-generation-of-cobblers; Johns, N. (2024, March 28). Veja launches its latest sustainable running shoe, the Condor 3. Footwear News. https://footwearnews.com/shoes/sneaker-news/veja-condor-3-sustainable-running-shoes-release-info-1203606282/; Segran, E. (2018, March 6). Veja wants to make the most sustainable shoe in the world. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/40532184/veja-wants-to-make-the-most-sustainable-sneaker-in-the-world; Blanchard, T. (2017, October 19). Green age kicks: How ethical trainers won the fashion seal of approval. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2017/oct/19/green-age-kicks-how-ethical-trainers-won-the-fashion-seal-of-approval; Drummond, J. (2015, September 16). Meet the most ethical sneaker brand in the world. Highsnobiety. https://www.highsnobiety.com/2015/09/16/sebastien-kopp-francois-morillion-veja-interview/; Trending: Footwear takes steps toward sustainability (2018, March 8). Sustainable Brands. https://sustainablebrands.com/read/trending-footwear-takes-steps-toward-sustainability; Poldner, K., & Branzei, O. (2010, November 26). Veja: Sneakers with a conscience. Ivey Publishing. https://www.iveypublishing.ca/s/product/veja-sneakers-with-a-conscience/01t5c00000CwgpIAAR ↵

- Veja. Taken from The Veja project (n.d.). https://project.veja-store.com/en/story ↵

- Veja sneakers cost more than five times as much to make as regular sneakers but sell for comparable prices. ↵

- Veja also uses vegetable-tanned leather (which uses acacia in the tanning process instead of chrome), and also offers shoe uppers made from recycled plastic bottles. ↵

- Drummond (2015). ↵

- Blanchard (2017). ↵

- Blanchard (2017). ↵

- This may be especially true if the extrinsic motivators are seen as controlling. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plentum; Kasser, T. (2003). The high price of materialism. Bradford Book, MIT Press. ↵

- Martin, M. (2018, March 10). Hockey night in Baker. Winnipeg Free Press, D5–D11. ↵

- See Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., & Piotrowski, M. (2002). Personality and job performance: Test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 1–9. Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 797–807. ↵

- Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. In M. R. Rosenzweig & L. W. Porter (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 41 (pp. 417–440). Annual Reviews. ↵

- Zell, E., & Lesick, T. L. (2022). Big five personality traits and performance: A quantitative synthesis of 50+ meta‐analyses. Journal of Personality, 90(4): 559–573; Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44: 1–26; Tett, R. P., Jackson, D. N., & Rothstein, M. (1991). Personality measures as predictors of job performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 44: 703–742; Van Aarde, N., Meiring, D., & Wiernik, B. M. (2017). The validity of the Big Five personality traits for job performance: Meta‐analyses of South African studies. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 25(3): 223–239. ↵

- Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., & Mount, M. K. (1998). Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83: 377–391. ↵

- Soutter, A. R. B., Bates, T. C., & Mõttus, R. (2020). Big Five and HEXACO personality traits, proenvironmental attitudes, and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(4): 913–941. Marcus, J., & Roy, J. (2017). In search of sustainable behaviour: The role of core values and personality traits. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–17. ↵

- Marcus & Roy (2017). ↵

- Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2009). The HEXACO–60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(4): 340–345 ↵

- “I propose that the key criteria for a need, basic or otherwise, are (a) that there is chronic, high, and universal value attached to the goals that serve it and (b) that successfully attaining goals related to that need is important for optimal well-being in the present and optimal psychological development in the future.” Dweck, C. S. (2017). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development. Psychological Review, 124(6): 689–719. ↵

- Maslow, A. H. (1955). Deficiency motivation and growth motivation. In M. R. Jones (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation. University of Nebraska Press. ↵

- Mitchell, T. R., & Daniels, D. (2003). Motivation. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 12 (pp. 225–254). John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4: 142–175. Alderfer, C. P. (1972). Existence, relatedness and growth. Free Press. ↵

- See also Dweck’s (2017) description of the need for acceptance. ↵

- Mitchell & Daniels (2003). ↵

- Herzberg, F. M., & Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley. ↵

- Bassett-Jones, N., & Lloyd, G. C. (2005). Does Herzberg's motivation theory have staying power? Journal of Management Development, 24(10): 929–943. ↵

- Muller, D., & Paluszek, A. (2017, December). How to do better: An exploration of better practices within the footwear industry. Change Your Shoes. http://labourbehindthelabel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/BP_report_final.pdf ↵

- Taylor, C. (2023, February 6). What the world’s longest happiness study says about money. Reuters; Kasser (2003). A materialist-individualist lifestyle may contribute to lower satisfaction with life (Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. [2002]. Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29[3]: 348–370); to poorer interpersonal relationships (Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. [1992]. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19[3]: 303–316); to an increase in mental disorders (Cohen, P., & Cohen, J. [1996]. Life values and adolescent mental health. Lawrence Erlbaum); to environmental degradation (McCarty, J. A., & Shrum, L. J. [2001]. The influence of individualism, collectivism, and locus of control on environmental beliefs and behavior. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 20[1]: 93–104); and to social injustice (Rees, W. E. [2002]. Globalization and sustainability: Conflict or convergence? Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 22[4]: 249–268). ↵

- Extending the argument a bit further, from a SET perspective everyone has an innate need to practice and to experience practical wisdom (evident in discerning and acting in the interests of the community); justice (evident when all stakeholders connected with an organization get their due); courage (evident when actions improve overall happiness, even at threat to self); self-control (evident when members overcome impulsive actions and the self-serving use of power). Surely members of such a community will achieve a healthy balance among a variety of forms of well-being. ↵