Part 3: Organizing

12. Human Resource Management

- Learning Goals

- 12.0. Opening Case: Mother Earth Recycling

- 12.1. Introduction

- 12.2. Component 1: Job Analysis and Design

- 12.3. Component 2: Staffing

- 12.4. Component 3: Training and Development

- 12.5. Component 4: Performance Management

- 12.6. Entrepreneurship Implications

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

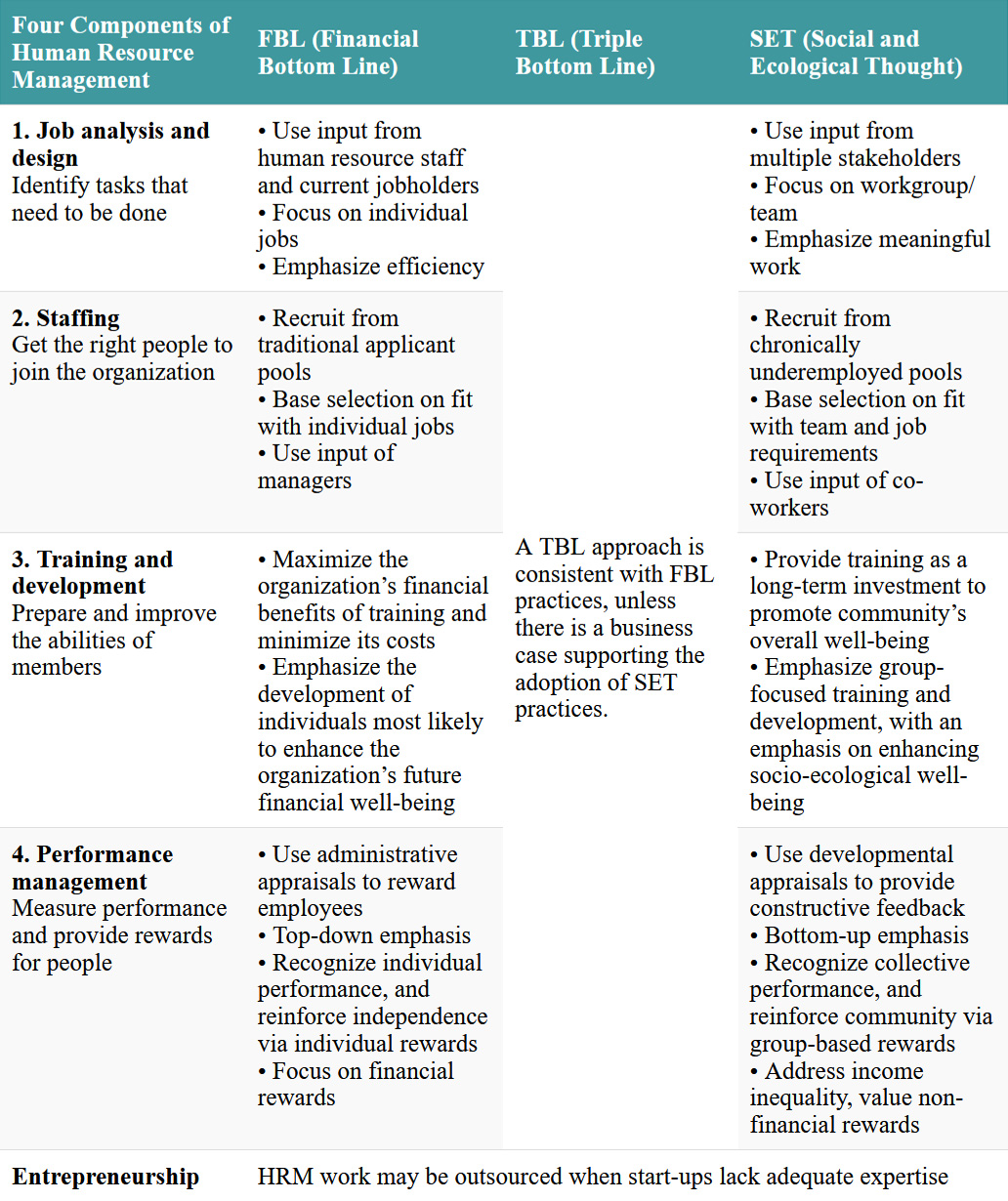

Chapter 12 introduces four key components of human resource management, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the four components of human resource management.

- Describe the differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to human resource management.

- Describe the elements of job analysis and human resource management planning.

- Identify and describe the two dimensions of staffing: recruitment and selection.

- Distinguish between training and development, and describe organizational practices associated with each.

- Describe the basic components of performance management.

- Describe how the increasing trend to outsource human resource management affects entrepreneurs.

12.0. Opening Case: Mother Earth Recycling

Mother Earth Recycling is a remarkable for-profit social enterprise based in Winnipeg.[1] It fosters ecological well-being by recycling electronic products like computers, televisions, smartphones, appliances, and so on. “We will take anything that plugs in or runs on batteries—whether it be broken, not working or still kind of working,” according to general manager Jessica Floresco.[2] Not only does the firm recycle this e-waste and keep it out of landfills, it also refurbishes what it can, and fosters social well-being by selling these items at greatly reduced prices in its storefront in a poor part of the city to people who would otherwise not be able to afford the products.

The company is not content with recycling only e-waste. It also has a successful and growing mattress recycling program. Mattresses are notoriously difficult to dispose of because they resist compression and release toxic chemicals into landfills. However, nearly 95 percent of the materials in mattresses can be reused for new products, like foam for carpet underlay and metal for cans. To keep mattresses out of landfills, Mother Earth offers its recycling program directly to customers as well as through partnerships with local government and private companies like Ikea. For example, a recent partnership with the City of Winnipeg aimed to recycle 8,000 mattresses in one year.

However, what makes Mother Earth Recycling most remarkable are its human resource management practices. First, Mother Earth is located in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Canada, where unemployment is especially high. To create social well-being, Mother Earth Recycling has designed its jobs so that many can be filled by entry-level employees with limited education or skills.

Second, Mother Earth deliberately recruits and hires employees who face multiple barriers to finding employment. In particular, Mother Earth is owned and operated by Indigenous people in a community where unemployment rates among Indigenous people are relatively high.[3] In partnership with community organizations, Mother Earth focuses on recruiting Indigenous people who have never had a job before, who may be in trouble with the law, or who did not graduate from high school (some of its employees quit school in Grade 8).

Third, it provides a six-month on-the-job training program, providing basic job skills. Mother Earth is especially pleased when employees are able to use its training and development to move on to better career prospects elsewhere. Floresco describes how “at the end of the six months, we’ll help them do a resume and help them learn to look for jobs and apply for jobs and help them get a better job.”[4] She goes on to describe an example: “We had one [employee] come and work for us, and they went from just getting out of a correctional facility and having no job experience, by the end of the training, they’d been accepted to [a local college] and going back to school and starting a career.”[5]

Fourth, the compensation practices at Mother Earth are designed to ensure everyone receives a sustainable wage, not to hire people for the lowest financial cost possible. Floresco explains: “It’s about getting that sustainable income, keeping families stable and safe in a stable environment and having a future to look forward to.”[6] Overall, it’s a wonderful example of what human resource management can do.

12.1. Introduction

Human resource management (HRM) is the set of organizational activities directed at attracting, developing, and maintaining a well-functioning workforce.[7] HRM has four components: (1) analyzing and designing the jobs that need to be performed in an organization; (2) recruiting and selecting staff to perform these jobs; (3) ensuring that jobholders receive appropriate training and development; and (4) ensuring that appropriate methods are used to appraise employee performance and administer rewards. HRM planning involves ensuring that an organization has the present and future human resources it requires to fulfill its mission and strategic objectives,[8] while at the same time adhering to the many laws related to employee relations. Employee relations refers to the activities that are necessary to effectively manage the relationship between employers and employees. This includes the legal responsibilities of employers to employees, along with activities covered in other chapters of this textbook such as coaching, leadership- and team-building efforts, conflict resolution, and disciplining the workforce as appropriate.[9]

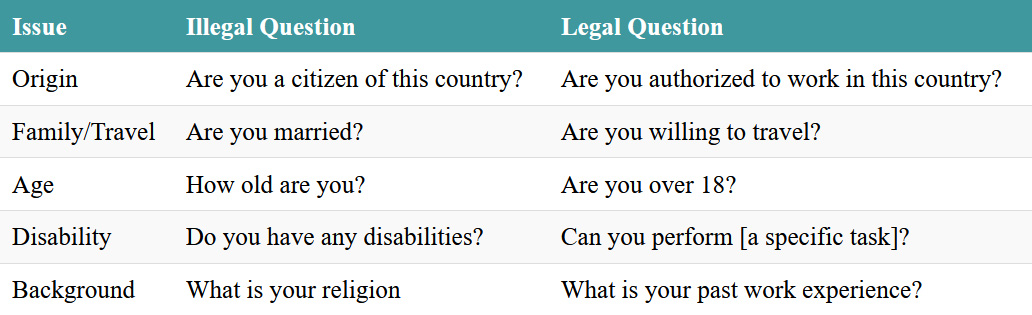

Before we examine the four main components of HRM, it is important to consider the legal context in which it operates. Many HRM activities are governed by legislation, especially the process of recruiting, selecting, and hiring new employees, where laws are in place to minimize discrimination. Discrimination is evident when someone is treated unjustly or badly based on characteristics such as their race, age, gender, or disability. Discrimination occurs when some applicants are not recruited or selected for reasons that are not job relevant. For example, companies have faced lawsuits for using social media platforms like Facebook to target recruitment efforts to people within certain age groups.[10] Many countries also have laws that require employers to provide accommodations for people with disabilities, such as making facilities accessible or modifying equipment, so they have equal opportunity to participate in the workforce. Organizations are held accountable for the legality of their HRM practices, even if illegalities are unintentional. A common situation where managers inadvertently violate employment law is in the interview process. Table 12.1 provides a few examples of illegal and legal questions in countries like Canada and the United States that might be asked during an employment interview.[11]

Table 12.1. Examples of legal and illegal questions in the selection process

Furthermore, in organizations where employees belong to a labor union, HRM practices must adhere to a collective agreement. A labor union is an organization that represents workers and negotiates with their employers (and in some countries, with the government) on the workers’ behalf. A collective agreement is a contract negotiated by employers and unions that specifies and regulates duties and responsibilities that employees and employers have to one another. Collective agreements often affect all four components of the HRM process, including recruitment and selection processes, criteria for hiring, promotions and layoffs, training eligibility, disciplinary practices, work hours, work rules, and seniority. In the United States, approximately 10 percent of the labor force is unionized,[12] in Canada 28 percent,[13] in China 44 percent, and in Iceland 91 percent.[14] Unions are typically formed to protect and enhance their members’ interests and overall social well-being through collective bargaining.[15] Collective bargaining is the process used when management negotiates wages and other terms of employment with a union or organized group of workers.

Relationships between HRM professionals and their counterparts in unions can be cordial and mutually supportive, with a win-win orientation (evident in countries like Germany), or more antagonistic and adversarial, with a win-lose orientation (often the case in the United States).[16] Unions may reinforce their bargaining position by threatening to strike (refusing to work), while managers may threaten to “lock out” striking members (refuse to let employees come to work) or to hire “strikebreakers” or “scabs” (non-union members hired to replace striking union workers). Sometimes businesses are guilty of exploiting and mistreating workers, and sometimes union activities contribute to violent and destructive encounters between employers, union employees, and replacement workers.[17]

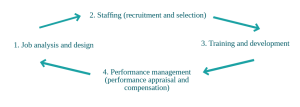

In the remainder of this chapter, we describe the four components or practices that make up HRM (see Figure 12.1). We will look at each of these in turn, considering differences between the Financial Bottom Line (FBL), the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and the Social and Ecological Thought (SET) approaches to human resource management.

Figure 12.1. Overview of four components of the human resource management process

12.2. Component 1: Job Analysis and Design

Although Figure 12.1 depicts job analysis and design as the first step of the HRM process, this component is often not revisited every time a new person is hired. Job analyses and descriptions are informed by the four fundamentals of organizing described in Chapter 10, ensuring that (1) work activities are designed to be completed in the best way for the organization; (2) assigned tasks are necessary to fulfill the work of the organization; (3) there is orderly deference among members; and (4) members work together harmoniously.

Job analysis is an investigative process of gathering and interpreting information to identify the requirements of a particular job. Job analysis can be seen as having two parts: (1) defining the tasks, duties, responsibilities of the job; and (2) identifying what knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) are necessary for jobholders to perform the job. Job analysis lays a foundation for other parts of the HRM process and results in the creation of job descriptions that summarize the duties and requirements of a position. A job description specifies what tasks are to be performed in a particular position, as well as the knowledge, skills, education and training, credentials, prior experience, physical abilities, and other characteristics that are required. A good job description that clarifies the position’s tasks and roles can help employers make good hiring decisions and improve employee satisfaction and performance.[18]

Several methods of collecting information can be used in job analysis. A formal job analyst or manager might collect data through observing someone else performing the job, or perhaps even by performing the actual job themselves. More often, job analysts generate a list of job tasks or KSAOs by interviewing or surveying subject matter experts who either hold the job or who observe the job regularly. One popular survey is the Position Analysis Questionnaire, a standardized questionnaire that asks respondents to rate the extent to which a job reflects a very detailed set of tasks and processes (approximately 200 questions).[19] Other approaches involve a jobholder filling out a job diary (which lists daily activities), or the analyst using external resources such as job descriptions and specifications available in the Occupational Information Network.[20]

Whereas job analysis aims to understand how jobs are currently performed within an organization, job design focuses on creating new jobs or making deliberate changes to the structure of existing jobs. When designing jobs, HRM professionals can manipulate a variety of job characteristics known to be related to jobholder performance and/or satisfaction. Job characteristics theory looks at the motivational effect of six job design factors on jobholder performance and satisfaction:[21]

- Autonomy refers to the amount of freedom, discretion, and independence jobholders have to schedule their work and determine the procedures to carry it out.

- Skill variety refers to the degree to which a jobholder must use a variety of different skills to perform a job.

- Task identity refers to the extent to which a whole or visible outcome is created by performing the job itself (for example, a janitor can see the difference between a dirty floor and a clean floor, whereas a nurse may not see any improvement in a patient’s health even after a twelve-hour shift).

- Feedback from the job refers to how much clear and direct information jobholders receive about how well they are doing their job (for example, a door-to-door salesperson gets direct feedback from each customer, whereas a policy analyst may not know if a policy has the desired outcome until far into the future).

- Task significance refers to how much of an effect a job has on the work or lives of others, both within and beyond the organization.

- Interdependence refers to how much jobholders collaborate with or rely upon others to do their jobs.[22]

Over time, job designs have shown increasing levels of job autonomy, skill variety, and interdependence. This is consistent with the trends toward more diffuse decision-making and flattening of hierarchies (autonomy), the increasing needs related to working in knowledge-based economies, and the extra skills needed to work in more complex team-based settings (skill variety and interdependence).[23]

12.2.1. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Job Analysis and Design

All three management approaches utilize job analysis and design, but there are differences in how these are accomplished and what is emphasized. All three draw on the professional knowledge of the HRM manager and the knowledge of jobholders, but a SET approach is more likely to include other stakeholders, such as employees from other departments and customers, to help develop job expectations and tasks. For example, Mother Earth Recycling consults with local non-government organizations (NGOs) to design jobs that are suitable for the skillset of the labor pool in its neighborhood.

The goals and emphases of job design also differ in ways that are consistent with the differences between the three approaches to the fundamentals of organizing (Chapter 11). For example, the FBL approach focuses on levels of standardization, specialization, centralization, and departmentalization. At one extreme, McDonald’s designs jobs that are highly specified and contribute to very efficiently operated restaurants. As such, a job at McDonald’s in Minneapolis, Manila, Monterrey, or Mozambique should essentially be the same.

In contrast, the SET approach will focus on experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation. Thus, a SET approach is generally more likely than an FBL approach to analyze and design team jobs than create individual jobs, where the tasks and KSAOs of the team are designated in the job description and specifications.[24] This is particularly true if an organization has self-managed teams (Chapter 16). Moreover, a SET approach involves a team’s members and its stakeholders in creating team job descriptions that include team-oriented KSAOs.

The SET approach is also more likely to include KSAOs that enhance social and ecological well-being, even if there is no business case to support them. This allows SET managers to embrace KSAOs that may not maximize profits. For example, consider Tim’s Place (“The world’s friendliest restaurant”), formerly owned and operated in Albuquerque by Tim Harrison, a man with Down syndrome.[25] Tim greeted customers at the door with a big smile and, if they wanted, gave them free hugs (by his count, over 70,000 hugs were given). This element of Tim’s personal KSAOs transformed going to a restaurant from being a (sterile) transaction and made it into a human experience (as Tim noted, “and the best part is, the hugs are free!”).

Other important differences among the three approaches to management are evident in how the six job design factors described above are managed. When designing jobs to be as efficient and productive as possible, FBL managers can be expected to place particular emphasis on the characteristic of autonomy, because research shows that autonomy is associated with both objective and subjective measures of productivity (note that four of the five remaining job characteristics are associated with only subjective measures of productivity—the exception is skill variety).[26] However, the productivity gains achieved via autonomy may be offset by increased expenses due to higher compensation and training costs.[27]

TBL managers will also emphasize the objective productivity benefits associated with autonomy and in addition be more aware of its beneficial reduced negative externalities, noting that autonomy can reduce financial costs because it is associated with decreased burnout and absenteeism. Thus, TBL managers may be more likely than FBL managers to embrace remote work, flextime, and other job design methods that enhance autonomy. Task significance and task identity also reduce burnout. Taken together, job characteristics like autonomy, task significance, and task identity are consistent with TBL’s openness to job crafting, where members design their own jobs to be meaningful, based on their own experience (see Chapter 5).[28]

Finally, a SET approach will seek to enhance all six job characteristics—even though five are not associated with increased objective gain in productivity—because each is positively associated with enhanced job satisfaction, growth satisfaction, and experienced meaning.[29] A SET perspective appreciates that some of these characteristics may also reduce costs associated with absenteeism and burnout, but these financial cost savings are not the main reason a SET approach embraces the six characteristics of job design.

Test Your Knowledge

12.3. Component 2: Staffing

Once job descriptions have been developed that support the overall organizational strategy, the next component to consider is the recruitment and selection of people for the jobs. Staffing is the HRM process of identifying, attracting, hiring, and retaining people with the necessary KSAOs to fulfill the responsibilities of current and future jobs in the organization. Staffing has two main components: recruitment and selection.[30] We will look at each in turn.

12.3.1. Recruitment

Recruitment is the process of identifying and attracting people with the KSAOs an organization needs. Key to the recruiting process is establishing and building recruitment channels, which funnel potential members into the selection process. A steady flow of potential members helps to ensure that the work of the organization can continue. Recruitment channels include colleges and universities, employment agencies, job fairs, internships, referrals by current employees, the organization’s website, and job board sites such as Monster.com or LinkedIn.

Social media is becoming increasingly important in recruitment.[31] Social media can enhance an organization’s reputation as a good place to work. For example, contributors to websites like Glassdoor and Vault Jobs describe their work experience with different employers. But an organization’s reputation can also be hurt by content posted by disgruntled employees or customers. For example, United Airlines experienced costly reputational damage when video footage of a passenger being forcefully removed from an overbooked flight went viral on social media.[32] Such incidents can make it difficult for a company to attract new employees. The internet also enables companies to search for and research potential and actual applicants without their knowledge or permission. Such data mining may be unethical and illegal and can lead to discrimination because it does not determine the validity or accuracy of information used. This is why it is important for organizations to establish codes of conduct regarding use of big data for staffing.[33]

Current employees can be an effective channel for recruitment, either in referring others to the organization or in filling positions themselves. Some organizations have a policy that gives preference to in-house applicants when recruiting for a position. Internal recruiting can be less costly if applicants have the necessary skills, and may help to improve members’ commitment, development, and job satisfaction.[34] On the downside, internal recruiting as a channel may not supply the necessary quantity or even quality of applicants.

Recruiting channels can be evaluated in terms of their speed and cost in delivering qualified applicants, that is, people who have the specified KSAOs. For example, web-based postings typically deliver a high quantity of applicants but not necessarily qualified applicants. To address this shortcoming, some sophisticated websites can screen applicants for the appropriate qualifications. Without such screening, receiving a high quantity of applicants requires extensive work by human resource professionals or managers to sift through applicant résumés, making this channel slower and less cost-efficient than other channels. In contrast, employee referrals or relationships with universities and employment agencies may provide qualified applicants in a shorter time and perhaps at a lower cost because these channels may screen applicants before recommending them to the organization.

Effective recruiting not only expands the pool of applicants to choose from at a reasonable cost, it can also improve the chances of retaining them once they are members. Although recruiters may be tempted to downplay negative features of a job or organization in order to “sell” the position, misrepresenting the job can have negative consequences after applicants are hired. A realistic job preview provides job applicants with information regarding both the positive and negative aspects of a position they are applying for.[35] Such information helps to match members with positions, improves job satisfaction, and reduces turnover. Turnover refers to “the rate at which employees leave an organization and are replaced.”[36] It is estimated that the financial costs associated with turnover of permanent employees is about 1.5 times their salary (e.g., to pay for recruiting costs, training, and so on).[37] Some information in a realistic job preview may be provided in the job listing, but at times it can only be experienced firsthand. For example, by providing potential new employees with a tour of the facility they would be working in prior to offering them a position, a slaughterhouse was able to reduce its employee turnover in their first week and thus also lower its training costs.[38]

12.3.2. Selection

Selection is the process of choosing whom to hire among a pool of recruited job applicants.[39] It may appear that the selection process begins once a pool of candidates has been recruited, but in reality selection begins already when the relevant KSAOs for the position are identified as the criteria for whom to select. Without justified criteria for selection, a manager or organization can get in legal trouble by being accused of making selection decisions based on criteria that are not relevant to the job, such as gender, race, or physical appearance. Once the job-relevant KSAOs from the job analysis and planning process have been identified, the next step is to choose the selection methods and tools that best assess these characteristics.

The most common selection tool is the application form that candidates complete to indicate interest in a position or organization. These forms, which are increasingly provided online, typically request information about an applicant’s educational background, previous job experience, and other job-related items. Applicants are often also invited to submit their résumés at the same time. The application form and résumé are then used by recruiters to make decisions about an applicant’s overall job fit (i.e., how well the applicant’s abilities match the demands of the job) by considering work-related skills and abilities, motivation, and personality.[40]

Although application forms provide valuable information to make a selection decision, additional methods and tools can be used to collect information that is more valid and reliable. Selection validity refers to the relationship between the scores applicants receive during assessment and their subsequent job performance. There are two ways to demonstrate validity:

- Predictive validation involves checking to see whether applicant scores correlate with actual job performance ratings.

- Content validation involves ensuring that the content of a selection method or tool assesses the actual KSAOs performed on the job.

You cannot have validity unless you have reliability. Selection reliability refers to the ability of a selection method or tool to consistently provide accurate assessments. For example, rather than assess someone’s personality using a single question (which might be misinterpreted), reliability increases by using multiple questions. Using multiple items that ask about the same characteristic adds to the reliability, but also to the length, of a selection test.

Selection methods and tests can take various forms. As shown on the continuum in Figure 12.2, having applicants provide a sample of the work they would do if hired for a job has high validity in predicting job performance. Such a test might have an applicant work on an assembly line if applying for a job in an auto plant, write computer code for a computer programmer position, or be tested on word-processing skills for a clerical position.

Figure 12.2. Validity of various selection methods for predicting job performance[41]

Like the application form, the interview is almost universally used as part of the selection process. Some organizations use a preliminary phone interview—or even an interview via text messaging[42]—to gather more information or to screen out people who are not a good fit with the job before they schedule face-to-face interviews. Some interviews are one-on-one, others are conducted by a panel, and often potential employees receive multiple interviews. Having more interviews or having more than one person conduct an interview increases the likelihood that the resulting judgment is reliable and less subject to the biases of individual interviewers.

Interviews may be structured or unstructured. In structured interviews, questions are decided upon in advance and related to specific job-relevant KSAOs such as resolving conflict or working in a team. All applicants are asked the same questions in the same order, and all responses are evaluated using the same rating scale. Unstructured interviews are more like conversations, where the direction of the interview may change based on the interests and background of each applicant. Although the distinction may seem minor, the differences in validity are not. Well-designed structured interviews have the highest validity of any selection method and are considerably more valid than unstructured interviews.

Interview questions also can take different forms, ranging from “how would you behave” to “how did you behave” questions. Situational interview questions ask applicants to respond to a specific scenario that is likely to arise on the job in the future (e.g., “What would you do if an irate customer threatened to sue the company?”). Behavioral interview questions ask applicants to draw from their experience to share an example of their work-related actions (e.g., “Describe a situation where you dealt with a difficult customer or team member”). Situational questions have the advantage of being more standardized and thus more reliable, as well as allowing questioning of those who lack experience in the specified area. Behavioral questions have the advantage of being based on experience (which is a strong predictor of future performance) and therefore are a bit more valid.[43] In any case, interviewers should be encouraged to take notes during interviews to minimize memory effects.[44] Often, managers will need to make judgments after interviewing several candidates, possibly after several days. Note taking helps avoid problems in recalling information such as the recency effect, which is the tendency to remember more about the last person interviewed.

Cognitive ability tests include questions designed to assess general mental ability, or more specific facets of ability such as verbal and numerical reasoning. These tests have moderate validity across a wide variety of jobs and are particularly useful for testing a large volume of job applicants, as well as for situations where applicants lack relevant experience or skills (e.g., entry-level hiring).[45]

Another selection tool that has moderate validity is personality testing, where sought-after traits often include conscientiousness, and—for people-oriented jobs—extraversion or possibly agreeableness (Chapter 14 has a fuller discussion of these personality traits).[46] Integrity (honesty) tests, despite concerns about faking, are more valid than standard personality tests in predicting job performance and also are valid for predicting counterproductive behaviors like stealing and absenteeism.[47] Some integrity tests ask direct questions about whether an applicant has taken home office supplies, lied about being sick, given away merchandise, or even stolen money from a past organization.

Finally, most organizations ask applicants to provide the names and contact information of references, which refers to people who can comment on an applicant’s educational background, work experience, or work ethic (e.g., a previous or current manager or teacher). As many as 95 percent of firms do reference checks, which are particularly helpful in confirming the educational and work-related information applicants have provided on their application form and in appraising the applicant’s characteristic and job performance capabilities.[48]

In addition to these traditional selection methods, organizations are increasingly leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) for staffing needs, such as developing hiring algorithms through machine learning or using chatbots to screen applicants. Despite the potential for increased efficiency and reduced human error, AI tools may introduce problems of their own.[49] For example, one of Amazon’s early attempts at developing an AI screening tool was canceled because the tool showed bias against women, a reflection of the biased data on which the model was created.[50] Employers must take care to use AI-enabled selection tools in ways that are valid and equitable.

In sum, a well-developed selection system typically involves multiple assessments. The use of multiple assessments increases the validity and reliability of selection judgments. This thinking lies at the foundation of assessment centers, where job candidates participate in a series of tests and simulation exercises over a period of two to three days. At the same time, organizations must consider the time and cost involved with using multiple assessments. The number of steps in a selection process typically varies depending on the nature of the job and its impact on the organization.

12.3.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Staffing

There are many similarities in the three approaches to staffing, but also important differences. First, in terms of recruiting, even though all three approaches recognize the merits of a diverse workforce,[51] the diversity evident in the broader society is often not reflected in who gets hired in organizations. For example, in the United States, unemployment rates among visible minorities[52] and the LGBTQ community[53] remain 50 percent higher than in the general population, and overall rates are even higher for people with a mild mental illness (31 percent unemployed),[54] neurodiverse people (up to 80 percent unemployed),[55] and ex-offenders (up to 60 percent unemployed),[56] to name a few. A TBL approach is more likely than an FBL approach to develop a business case showing that recruiting from some non-traditional applicant pools can benefit the organization. For example, hiring people with disabilities can provide unique or special skills, improve organizational culture and productivity, and enhance a company’s public image.[57] In an organization like Specialisterne, which focuses on employment opportunities for people with autism, what is generally considered to be a disability is transformed into an ability that can command premium financial compensation.[58]

A SET approach to recruitment goes one step further and is the most likely of the three approaches to target chronically underemployed populations, as we saw with Mother Earth Recycling.[59] Recall from Chapter 1 Greyston Bakery’s mission, as reflected in its motto: “We don’t hire people to bake brownies; we bake brownies to hire people.” Greyston uses what it calls an open hiring process to recruit chronically underemployed people, such as homeless people and ex-offenders, who apply for jobs simply by adding their names and contact information onto a waiting list—no résumés or references required. Since its inception, Greyston has been able to create over 3,500 jobs that pay a living wage and has launched a consulting business to help other organizations wanting to do the same thing.[60]

Moreover, beyond hiring chronically underemployed people in order to help them, a SET perspective recognizes that doing so can help everyone. For example, as described in Chapter 5, because the FBL approach sees meaningful work as related to tangible achievements (e.g., money) and enhancing one’s interests vis-à-vis others (e.g., getting ahead), it follows that FBL managers will value and hire people who facilitate this (the best and the brightest). As a result, this (unintentionally) becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy for members to be preoccupied with materialistic and individualistic thinking. It also excludes people who may have developmental or other challenges that make them marginally less productive. In contrast, people who work alongside and appreciate co-workers who reflect the diversity of society will be more inclined to learn that meaning does not depend on maximizing money and getting ahead. Indeed, as we have seen, materialism and individualism actually reduce people’s life satisfaction.

A powerful example of this insight is evident in an observation from Henri Nouwen, who left a successful twenty-year career as an academic at Harvard and Yale Universities in order to work at an organization called L’Arche. Nouwen called this one of the most important experiences of his life because it compelled him to (re)discover his “true identity.”[61] In terms of meaningful work as described in Chapter 5, Nouwen’s daily work alongside people with intellectual disabilities reminded him of the fleetingness of sources of meaning that are materialistic (his tangible achievements and financial success) and individualistic (his abilities to enhance his own identity and interests over those of others). Other possible benefits that can come from such ongoing relationships include an increased sense of tolerance, compassion, thoughtfulness, awareness of and care for others, and appreciation for life.[62]

Second, in terms of the selection process, a SET approach is most likely to include a wider variety of organizational stakeholders in interviews and in making selection decisions. Team members and peers may also be included in panel interviews in FBL and TBL organizations, but SET organizations are more likely to give hiring authority to team members. A SET approach is consistent with relying on self-managed teams to do recruiting and hiring for their teams, as illustrated by Semco (opening case, Chapter 10).

The SET approach to staffing also differs from FBL and TBL approaches in other predictable ways. In particular, because the KSAOs developed in a SET approach are more likely to include knowledge and abilities related to socio-ecological well-being,[63] interviews in SET organizations are more likely to discuss practices that promote social and ecological well-being and ask applicants about their ability and desire to contribute to such efforts. Research suggests that the SET approach’s emphasis on promoting social and ecological well-being may make it easier to recruit younger and more educated people.[64]

Test Your Knowledge

12.4. Component 3: Training and Development

Once the organization’s human resources needs have been determined (job analysis and planning) and recruiting and selection have been completed (staffing), it is time to consider employee training and development.

12.4.1. Training

Training refers to the provision of learning activities that improve a jobholder’s skills or performance. On average, organizations in the United States spend over $1,000 per employee per year on training.[65] The first exposure most employees receive to training is new member orientation programs that may run for a few hours or a couple of weeks. During orientation, new members become familiar with the people in their workgroup, its goals, and how their job fits with those of co-workers. Orientation provides an introduction to the organization’s history, mission statement, key leaders, and human resource policies (e.g., work hours, overtime policy, benefits). New members often receive a tour of the organization as part of their orientation. Orientations may be very formal (such as a one-week course off-site) or informal (“Here’s Sally—she’ll take you around and introduce you to some of the people you’ll be working with”). This early training is an important form of socialization that helps new employees navigate their new work environment.

On-the-job training is the most common training method. On-the-job training (OJT) occurs when someone who knows how to perform a particular task shows and teaches someone else how to do it. When it works, OJT is considered to be a fast and effective form of training.[66] OJT is tailored to the specific knowledge and skills employees need for their job, and provides trainees with immediate opportunities to practice new tasks.

OJT is not appropriate for every training need. When tasks are too complex to learn by OJT or when OJT causes too much disruption to normal operations, organizations will use off-the-job training methods like formal education, classroom lectures, videos, and simulation exercises. In these off-the-job training environments, the successful transfer of the training to the everyday work environment depends on several factors.[67] First, training should be offered to those who have an interest in and aptitude for the training. In other words, trainees must be willing and able to be trained. Second, the training content itself must be relevant and the instructions designed so that trainees are given multiple opportunities to practice using each component of the target skill or knowledge domain. The objectives of the training are reinforced before, during, and after the training experience. Third, there must be support for applying the training in the work environment. Many employees have returned from training enthusiastic to apply what they have learned, only to find no immediate opportunities for or interest in using that training on the job. For example, a manager who attends a seminar to learn how to better perform job interviews may not be involved in hiring anyone for the next six months. A supportive work environment can be created by a manager who is committed to encouraging investments in training, finding opportunities to apply training, and recognizing improvements gained through training.

Managers who take training seriously also take the time to measure training effectiveness.[68] Although in most organizations trainees are asked to provide their reactions immediately after training—and in some cases, organizations attempt to assess learning through pre- and post-tests—very few organizations take the time to systematically link training to behavioral change or business results. A comprehensive HRM system allows for such measurement. For example, if specific KSAOs are identified in the job analysis (or perhaps in the training needs analysis) and are measured in the performance appraisal, training that specifically addresses those KSAOs can be evaluated by tracking progress in performance appraisal ratings. In some cases, training can be tied to business results, such as when training in quality improvement leads to decreases in defects or waste that improve the performance of a manufacturing plant. However, in many other cases it is difficult to prove the direct business benefit of training.

12.4.2. Development

Development refers to learning activities that result in broad growth and training beyond the scope of one’s current job. Development practices may include becoming familiar with other departments or facilities in an organization (and perhaps transferring from one department to another). Some organizations engage in cross-training or job rotation, where employees receive OJT in a variety of positions in the organization, thus permitting them to better understand how their job fits into the overall organization and providing flexibility for the organization if another member is unable to come to work for an extended period of time. Development can also include being assigned challenging or novel projects, being mentored by senior managers, and participating in formal career-planning discussions. Development is also evident when a firm pays for employees to attend professional seminars and training sessions that go beyond the scope of their current job, or to enroll in MBA or other graduate degree programs.[69]

Development can be seen as having two general purposes. The first is to allow workers to grow as persons. Development of this sort may sometimes be supported by a business case, for example, showing that development increases employee motivation and productivity (consistent with the job characteristics model), or that it enables cost saving thanks to a more flexible workforce. Development enables employees to become more creative, as they have a more holistic understanding of the firm and how its different parts work together (see sensitization in Chapter 10).[70]

Second, career development can be an important part of the HRM planning process that ensures an organization has adequate human resources prepared to fill jobs at higher levels in the organization’s hierarchy. A succession plan refers to identifying and grooming talented employees who have the potential of doing well in jobs of increased responsibility within the organization. Organizations can use succession plans for a variety of reasons, from ensuring enough talent is in the pipeline to seeing that a sufficient number of underrepresented people (often women or minorities) are advancing through the system. Unfortunately, many organizations either have limited succession planning or none at all.[71]

12.4.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Training and Development

FBL and TBL managers focus on training and development activities that are linked to increasing a firm’s net financial performance.[72] In contrast, SET managers are more likely to also support training and development for its own sake, even if it does not obviously contribute to the financial bottom line. There are at least two general variations of such a SET approach to training and development.

First, some SET organizations are specifically designed to provide training and development to employees who will essentially “graduate” from the organization. This is evident in organizations like Greyston Bakery, BUILD, and Mother Earth Recycling, which deliberately recruit and select workers from chronically underemployed populations (e.g., formerly incarcerated people, individuals with no high school education) in order to train and develop them so that they can find other jobs elsewhere. Such organizations will also often provide life skills training for their workers (e.g., skills in managing their personal finances, parenting, cooking, and so on).

Second, whereas FBL and TBL organizations focus on providing job- or organization-specific training that will increase productivity and financial well-being, SET organizations also deliberately provide training and development for their employees that goes beyond what they do in their everyday work but instead enhances overall organizational and community socio-ecological well-being. Recall that Montreal’s Tomasso Corporation encourages and pays its senior managers and other employees to help out in soup kitchens, thereby encouraging them to become more well-rounded people and to think beyond typical FBL and TBL considerations when making decisions for the company (including subsequent decisions about whom to hire at Tomasso).[73]

Test Your Knowledge

12.5. Component 4: Performance Management

Performance management refers to the HRM processes that are designed to ensure that individual and team activities and outputs are aligned with the organization’s strategic goals.[74] Performance management has two components: performance appraisal and compensation.[75] Performance management can be seen as a particular example of the general four-step control process described in Chapter 18, which starts with establishing performance standards, monitoring and evaluating performance, and responding accordingly.

12.5.1. Performance Appraisal

The performance appraisal process serves as the foundation of an effective performance management system. Performance appraisal specifies, assesses, and provides feedback to jobholders regarding what they are expected to do. Appraising employee performance can be challenging and stressful, especially when providing feedback to poor performers or when making distinctions among employees to decide who will receive bonuses or raises. Being on the receiving end of poor appraisals can also be stressful; employees often complain that perceptions and politics influence ratings more than actual performance does.[76]

However, performance appraisals do not need to be frustrating experiences that both parties disdain. Performance appraisals can be valuable in conveying important information and aligning employee behavior with organizational goals if the following steps are taken:

- Design a system for appraisal with a clear purpose, defined roles, and agreed-upon criteria.

- Equip the people doing the appraising with the skills and tools to be successful.

- Reinforce and review the appraisal process.[77]

1. Design a System

When designing an appraisal system, it is important to decide what criteria will be used for the appraisal, what type of appraisal it will be, who will be doing the appraising, and how often appraisals will take place. First, the system should spell out clearly what performance is expected from the employee. Appraisal criteria are based on the job description and the organization’s goals.

Second, managers have two types of appraisals to choose from: administrative and developmental. Administrative appraisals justify pay, promotion, and termination decisions. For example, organizations like Amazon, Meta, and Uber[78] have used performance appraisal information to promote and to fire employees using the “rank-and-yank” system inspired by General Electric’s former CEO Jack Welch. The system comparatively rates or ranks employees, and top performers get rewarded and low performers get fired or put on performance improvement plans. Developmental appraisals provide feedback on progress toward expectations and identify areas for improvement, and can be used in combination with training and development processes described in the previous section. In practice, most organizations use administrative appraisals on an annual or semi-annual basis, and fewer organizations use formal developmental appraisals. In either case, it is important to communicate to both managers and employees what the appraisal information will be used for.

Third, managers can design single- or multi-rater appraisal systems. In a fairly simple system, the appraising might be done by an employee’s supervisor. A more elaborate method, called 360-degree feedback, relies on self-report ratings combined with input from a full circle of people who work directly with the member whose performance is being appraised.[79] Members of the appraisal group can include supervisors, co-workers, subordinates, and internal and external stakeholders. Clarifying who will be involved in the appraisal process helps to ensure perceptions of fairness; no one wants to be surprised by who is providing input into decisions about their performance. An advantage of the 360-degree feedback method is that it increases the quantity and variety of information while reducing the bias that might come from using a single rating source. Shortcomings of this method are that it may fail to provide feedback to ratees that they can use to improve their performance,[80] and it may be prone to employees using it to anonymously “get back” at a boss, or to managers coercing their subordinates to give good evaluations.

Fourth, managers must decide how frequently to conduct appraisals. Although annual appraisals are most common, many companies are shifting to a “continuous performance management” approach that encourages ongoing feedback between managers and their employees.[81] An advantage with more frequent appraisals is that areas for improvement can be identified and addressed in a more timely manner. Providing informal developmental appraisals on an as-needed or variable schedule may be particularly effective at maintaining desired behaviors (see Chapter 14).

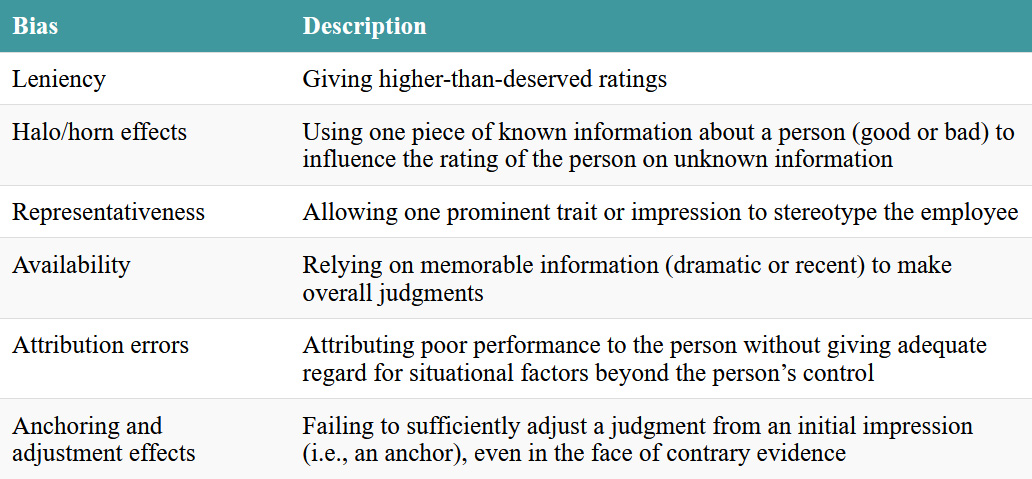

2. Equip Appraisers

The second step in the performance appraisal process is to equip appraisers with the knowledge and tools that will help them make accurate ratings.[82] One type of appraiser training, sometimes called frame-of-reference training, is meant to increase the accuracy and reliability of ratings by providing raters with a common understanding of what constitutes high, medium, or low performance. Another type of training focuses on making raters aware of common biases such as those listed in Table 12.2 and urging them not to commit these errors:[83]

Table 12.2. Common rater biases that cause errors in making performance appraisals

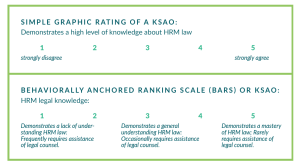

The performance appraisal form is the primary tool for rating. Typically, a rating form has one or more of the following elements: (1) questions that rate specific KSAOs or characteristics; (2) assessments of progress toward goals; and (3) a summary judgment or rating.

First, most performance appraisal systems rate an employee’s KSAOs.[84] Graphic rating scales are one of the oldest and most popular methods to appraise KSAOs. This method often uses a 5-point scale where raters are asked to assess the degree to which they agree a characteristic is descriptive of a person. A more advanced type of graphic rating scale is called the behaviorally anchored ranking scale (BARS), which focuses on specific behaviors of members. Table 12.3 illustrates these two types of rating scales. Because BARS items and their rating scales are more closely related to specific descriptions of work behavior, they are more valid and reliable than a simple graphic rating scale.[85] Some rating forms go one step further in asking raters to provide a graphic rating as well as specific examples of performance to justify the rating.

Table 12.3. An example of two ways to rate a manager’s legal knowledge of HRM

Second, about 80 percent of rating forms refer to the progress the person being rated is making toward specific goals.[86] Often the focus is on easily measured outcome goals (e.g., reaching a sales goal), with less attention given to how the outcomes are achieved (e.g., treating customers with dignity).

Finally, regardless of the types of ratings that are provided, an appraisal typically ends with a summary rating. This may be “subjective,” when the rater is asked to give an overall judgment of the employee’s performance, or “objective,” when the individual item ratings are combined mathematically to yield an overall score.[87] For example, an employee in the human resources department may score low on one item (perhaps a 2 on legal knowledge of HRM) but score high on other items, giving that person an overall rating score of, say, 4.2.

3. Reinforce and Review the Process

A third key element of performance appraisal is to reinforce the importance of the appraisal process, subjecting it to regular review and continuous improvement to ensure that it remains relevant and reliable. An important symbolic way to reinforce the importance of the appraisal system occurs when top managers model a thoughtful, thorough, and timely approach to their own appraisals of others. Research suggests that a review process that invites input from all participants can have a positive impact on employees’ acceptance of the process and is almost universally beneficial[88] (e.g., employees participate in developing the performance appraisal system in about 50 percent of US firms[89]). Many criteria can be used to evaluate the performance appraisal system, including its perceived fairness and accuracy, whether it helps members and the organization to achieve their goals, and whether it proceeds in a timely manner.

12.5.2. Compensation

Compensation is the second component of performance management. Compensation refers to monetary payments such as wages, salaries, and bonuses as well as other goods, commodities, and intangible rewards that are given to organizational members.[90] In terms of financial rewards, there are two basic types of compensation systems: job-based pay, and pay for performance. Job-based pay refers to a standardized system where employees receive financial rewards based on their position title. There is usually some variability across employees holding the same position based on work experience or job tenure, but the pay scale usually is “banded” (that is, it is constrained by a predetermined minimum and maximum). The pay range for a position can be determined by comparing it to other jobs in the organization, and/or by comparing it to similar jobs in the market.

Pay for performance refers to a system where employees’ compensation is based on activities and outputs of individual employees, and/or their workgroup, and/or the entire organization.[91] Most companies offer some form of pay for performance, or incentive pay. The simplest pay-for-performance system is piece rate, where an employee gets paid a set amount of money for every unit of work they perform (e.g., a carpet installer who gets paid $5 for every square foot of carpeting installed). Salespeople often work on an individual commission basis, where their compensation is tied to their sales, and they may also receive additional rewards for meeting specified goals. Merit pay programs link pay to performance appraisal ratings and reward top performers with pay increases or bonuses. Pay for performance also can include gain-sharing plans (where a group of employees is rewarded for reaching agreed-upon productivity improvements); goal-sharing plans (where a group of employees receives bonuses for reaching strategically important goals); profit-sharing plans (where a portion of an organization’s profits is paid to employees); and stock option plans (where employees earn the right to purchase shares of their organization at a potentially reduced cost). Consistent with agency theory (Chapter 6), these types of compensation systems align employee incentives with an organization’s strategic goals.[92]

Many organizations use compensation systems that have elements of both job-based pay and pay for performance. For example, restaurant workers are paid a small hourly rate plus what they earn in tips (either individually or shared with others). Another variation is evident in skill-based pay systems, where employees get paid a base hourly wage rate for doing their job, and then get additional increments for acquiring other skills that are valuable to the organization (such a system was championed by Michael Mauws at Westward Industries—see opening case, Chapter 18).

When the word “compensation” is mentioned, most people think about someone’s salary or wage, but compensation also includes the idea of benefits, which are non-pay-based compensation. Benefits include things like health, disability, and life insurance, retirement plans, and perks such as access to exercise facilities, on-site daycare, subsidized cafeteria food, education reimbursement, and laundry services. To enhance employees’ appreciation of benefits, some organizations offer so-called cafeteria-style benefit plans that present an array of possible benefits and allow members to pick and choose which benefits they want (up to a certain maximum dollar amount). Although some motivational theories dismiss benefits as unimportant in motivating employees, research suggests that benefits influence employee attraction and attrition, and that having a choice of attractive rewards can increase performance significantly.[93]

Finally, in addition to the tangible benefits mentioned above, there are also intangible benefits. For example, each year several organizations publish lists of “the best places to work.” Individuals who work at companies that rank high on these lists may attach some significance to this intangible benefit, and it may reduce their desire to leave the company even if they are not particularly happy about the tangible rewards they are receiving. Other intangible benefits include workplace friendships and the camaraderie that results from working with people who are fun to be with.

12.5.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Performance Management

Performance management in all three approaches to management involves performance appraisal and compensation.[94] FBL, TBL, and SET management approaches follow the same three steps of performance appraisal (design a system, equip appraisers, and reinforce and review the process). However, there are notable differences in how they enact each step and the emphasis they place on specific factors. For example, whereas the FBL and TBL approaches are more likely to use administrative appraisals, the SET approach is more consistent with the use of developmental appraisals where raters are skilled in expressing gratitude to employees, providing constructive and more frequent feedback, and facilitating discussions regarding areas for growth and improvement.

Another difference is that a SET approach is more likely to involve a greater variety of stakeholders in all three steps, whereas FBL management is more likely to use a top-down approach that involves supervisors and higher-ups. Thus, SET managers welcome the involvement of employees when developing appropriate performance appraisal systems; this ensures that all stakeholders have the required information to make appraisals, and all are involved in reinforcing and reviewing the process.[95] For example, at Semco, employees have work councils and are encouraged to unionize, which provides an additional avenue to provide their input into the performance appraisal process (see the opening case in Chapter 10).[96] Recall that at Semco, employees choose their own managers and set their own salaries. In order for employees to make informed choices, management provides them with training on how to read the firm’s financial reports (an “open book” policy), information about how their managers are perceived by others, and information about the salaries of their co-workers and the pay scales used by other businesses in the industry.

A traditional FBL approach to performance management has tended to focus on managers appraising and rewarding individual members’ performance, though with the growing emphasis on teams in businesses, this is changing. Team-oriented reward and feedback systems are often a practical necessity, as it is often impossible to separate out the contributions of individuals when work tasks are highly interdependent (see Chapter 16).[97] Rating team performance is entirely consistent with the low emphasis on individualism that characterizes the SET approach. Team-based HRM systems, which appraise and reward at the group level, encourage cooperation and flexibility in accommodating the views of other group members and other stakeholders. When all team members share in the success of the team, its members are more likely to share tactical or technical information broadly and help solve problems that benefit the whole group. An emphasis on teamwork does not preclude rewarding high-performing individuals within the group. Indeed, several times the owner of Velo encouraged employees to give themselves a raise. In one case at Semco, when a high performer did not choose a high enough salary, other team members insisted he give himself a raise.

Finally, when it comes to financial compensation, the SET approach has a distinctive emphasis on policies that reduce income inequality. On the one hand, SET organizations often pay their lower-level employees at above-market rates in order to ensure that everyone is paid a living wage. On the other hand, SET organizations often pay their higher-level employees at below-market rates. For example, Nathaniel De Avila, the owner-manager of Velo Renovation (Chapter 9), is not the highest-paid person at the firm. He recounts how, when employees were asked what to do if at year-end the firm had made more than enough profit (De Avila was leaning toward paying everyone a bonus), some responded with:

“Well, what if I don’t really want more than [what I was paid]?” Which is also a surprising comment, I guess. But my response was, “Well then, what should we do with it?” Because in my mind it’s not mine to decide what to do with. One person was like, “Well, what if we just hire some derpy teenager to work for us next summer, and like they don’t know what to do, but I can get paid to teach them. Which makes me feel great, and maybe it’s someone who needs a job and then that’s great, too!” That was a little bit mind-boggling to me. That’s a very selfless way to think about your own employment, too. Like would you give up your extra money so that someone else could have a job?

De Avila does not know why his employees responded to the idea of how to share year-end surpluses in the way they did, but he observes that “selfless behavior around money is transferrable. So once sharing is patterned and exemplified in some way, like ‘this is an okay way to operate,’ it’s possible that some people also want to jump on the bandwagon. But not in any sort of forced way.”[98] This is consistent with the emphasis in virtue ethics on everyone having enough (and that it is unethical to have too much).

Test Your Knowledge

12.6. Entrepreneurship Implications

Human resource management is a particularly important consideration for entrepreneurs. Because most start-ups are relatively small and organic in structure, every employee can play an influential role in organizational success. While it is important for all organizations to have the right people completing tasks, it is especially so in the smaller, less formalized setting of a start-up. For example, if a start-up only has six people in it, every one of those people can have a powerful effect on the organization. It is therefore crucial for entrepreneurs to manage HRM matters effectively.

Many organizations, entrepreneurial and otherwise, choose to outsource HRM duties. Unless an organization is quite large, it may not benefit from sufficient economies of scale to support the costs of an internal HRM function. As well, because of the technical and legal complexities associated with some aspects of HRM, it often makes sense to outsource to experts. For example, very few organizations manage their own retirement plans; instead, they invest in funds managed by other organizations that specialize in wealth management. Likewise, most work-based insurance and health-related benefits are provided through outsourcing relationships. All aspects of HRM—job analysis, staffing, training, and performance management—can potentially be outsourced. This fact may help to simplify entrepreneurial start-ups, since founders do not have to worry about the technical and legal aspects of HRM. At the same time, this outsourcing can also provide entrepreneurial opportunities: an entrepreneur with HRM knowledge could start a new organization to respond to the outsourcing demand from others.

In fact, the outsourcing of HRM is on the rise in most organizations through the use of contingent workers. Contingent workers are individuals who are contracted for a specific project or fixed time period but are not considered to be permanent employees of the host organization.[99] Contingent workers, who are sometimes called “temps” (short for “temporary workers”), are employed by staffing agencies like Randstad, Adecco, and Manpower.[100] These agencies and others like them provide contingent workers to organizations on demand, thereby taking over much of the traditional HRM function. Using contingent workers serves to reduce payroll and benefit costs (e.g., health insurance, retirement plan contributions) and to increase flexibility for employers. In a 2023 survey, 80 percent of company leaders across the globe said they use contingent workers, and 65 percent said they plan to increase their use of contingent workers over the next two years.[101]

In the past, most temporary workers were in low-level clerical and manufacturing positions, but a growing number today are professionals. In fact, there are contingent workers doing almost every kind of work.[102] There have always been contingent workers (e.g., ski resorts only hire staff in the winter, brick-and-mortar retailers hire more part-time staff during major shopping seasons), but their use has become increasingly common. As a result, the entire notion of a “job” may be changing. Some estimates suggest that over one-third of workers are in contingent positions rather than being traditionally employed within a single organization.[103]

This change in work has been sped up by the development of technology, which makes it easier to establish contingent relationships that weren’t practical in the past. For example, think about how Uber and other ridesharing organizations have changed transportation. In most cases, Uber drivers are not employees of Uber; they are treated as independent contractors (i.e., contingent workers).[104] As a result, most of the traditional HRM functions don’t apply for Uber drivers. Recruitment consists only of confirming basic qualifications (e.g., ability to drive, clean background check), little training is provided, and compensation comes from the consumer rather than from Uber. Similar changes are taking place in many industries (e.g., Airbnb in the hospitality industry).

Because so many jobs are contingent, observers have begun to refer to modern work as the “gig economy.”[105] In this context, a “gig” is a temporary job; the individual is hired for a fixed fee or time period to complete a specific task. Recently, most of the new jobs created in the United States were gigs,[106] and gigs may soon be more common than traditional employment.[107] If these predictions come true, most workers will not have permanent employers, and people won’t have a job but rather a series of gigs that they must find and combine to build their career.

The rise of the gig economy influences entrepreneurship in many ways. With more gig workers available and better platforms for accessing them, entrepreneurs now have far more flexibility in terms of make vs. buy decisions (see transaction cost theory in Chapter 7). For example, the idea that a hotel company could not only exist but expand internationally, without owning any real estate or hotels, may have seemed impossible in the early 2000s, but as of 2023 Airbnb had more than 8 million lodgings listed in more than 200 countries and had facilitated over 2 billion guest stays.[108]

The gig economy also raises questions for entrepreneurs about employment relationships. This development is too new for certain conclusions, but we can likely expect FBL entrepreneurs to favor gig work and contingent employees. Using contingent workers offers many ways to save money (reduced HRM costs, more flexibility in staffing, simpler dismissal of undesired workers). Likewise, TBL entrepreneurs will presumably embrace these cost-saving opportunities while extolling the personal flexibility and lifestyle freedoms that gig working can provide. For example, a parent who is the primary caregiver for school-age children may benefit from the option to not work during parts of the year (e.g., school holidays). A SET entrepreneur’s likely attitude regarding gig workers is harder to predict. The lifestyle and flexibility aspects of contingent work would be seen as attractive, since they can contribute to family, community, and personal growth. In fact, research evidence suggests that some workers prefer gig work to traditional jobs, seeing it as an opportunity for more variety, control, and meaning in their work.[109] At the same time, however, gig workers have less stability and certainty than traditional employees, they usually make less money, they are more vulnerable to mistreatment by employers, and they must bear the burden of work usually handled by the HRM function (e.g., income tax withholding, medical benefits, paid vacation).[110]

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

There are four components in human resource management (HRM):

- Job analysis identifies the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) that are necessary to perform a particular job; and HRM planning combines all the KSAOs needed in an organization and determines how to acquire them from the market.

- An FBL approach is more likely to focus on individual jobs and KSAOs, input from existing jobholders, efficiency, and the use of contingent workers.

- A SET approach is more likely to focus on team-oriented job analyses and KSAOs, input from a variety of stakeholders, meaningful work via job crafting, and hiring permanent workers.

- A TBL approach is consistent with FBL practices, unless there is a business case for adopting SET practices.

- Staffing involves both recruitment (identifying and attracting people with the KSAOs an organization needs via recruitment channels and practices like realistic job previews) and selection (choosing which applicant to hire via selection methods like application forms, interviews, cognitive ability tests, and work samples).

- An FBL approach is more likely to use administrative appraisals, recruit from traditional applicant pools (e.g., internet jobs sites), select applicants based on fit with individual jobs, and have hiring decisions made by managers or human resource professionals.

- A SET approach is more likely to use developmental appraisals to recruit from non-traditional applicant pools (especially chronically underemployed groups), select applicants based on organizational fit (e.g., fit with team-based KSAOs, agreeableness, diversity), and have hiring decisions made by a variety of stakeholders.

- A TBL approach is consistent with FBL practices, unless there is a business case for adopting SET practices.

- Training involves activities where a jobholder learns to improve their skills or performance, such as on-the-job training; and development involves learning activities that result in broad growth beyond the scope of one’s current job.

- An FBL approach is more likely to use training and development to improve financial performance and reduce financial costs (evident in use of contingent workers, providing job- or organization-specific training).

- A SET approach is more likely to use training and development to improve overall well-being and reduce overall costs (evident in training the chronically underemployed, providing life skills training, and fostering group-focused social connections that enhance socio-ecological well-being throughout the organization and toward disadvantaged segments of society).

- A TBL approach is consistent with FBL practices, unless there is a business case for adopting SET practices.

- Performance management involves both performance appraisal (specifying, assessing, and providing feedback to jobholders regarding their work via designing an appropriate system, training appraisers, and continually improving the process) and administering compensation (monetary and other rewards for members).

- An FBL approach is more likely to use administrative appraisals, equip supervisors and managers to design and control the process, focus on individual-level appraisal and rewards, design compensation systems that are consistent with the marketplace, and emphasize financial well-being.

- A SET approach is more likely to use developmental appraisals, invite and equip a variety of stakeholders to be involved in the process, focus on group-level appraisal and rewards, design compensation systems that reduce income inequality and at minimum pay a living wage, and emphasize socio-ecological well-being and meaningful work.

- A TBL approach is consistent with FBL practices, unless there is a business case for adopting SET practices.

Finally, entrepreneurs often outsource components of the HRM process where they lack expertise.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Keeping job analysis and planning information up to date can be a time-consuming and laborious task. If you were asked by someone whom you are managing to explain why job analysis and HRM planning is worth the time, what would you say?

- Do the selection processes you’ve experienced (or heard about from others) seem fair to you? Why or why not?

- Think of a time when you were interviewed for a job. Was the interview structured or not? Did you get any strong impressions that would allow you to classify it as an FBL, TBL, or SET organization? If so, elaborate. What advice would you have for interviewers from organizations associated with each of the three approaches to management?

- What are the pros and cons of hiring people who might be the best and brightest for an organization but not for a particular job?

- Recall an experience of working in a group in which you were aware that some people had disabilities and others did not. What have you learned about yourself from such experiences?

- Explain the difference between an administrative appraisal and a developmental appraisal. Which would you rather receive? Which would you rather give? Why?

- One poll found that twice as many people would choose a low-paying job that they love over a high-paying job that they hate.[111] What about you? What are the key non-financial rewards that can make a low-paying job more attractive than a high-paying job? What are the implications of your answer for HRM?

- Have you ever been a contingent worker or worked with contingent workers? What are the pros and cons of hiring a contingent worker, of working with one, and of being one?

- If you were to start your own organization, which parts of the HRM process would you outsource, and which would you manage yourself? Explain your answer.

- This case is based on information found in Dufour, A. (2023, October 23). Disposing of a mattress is ridiculously hard. So is the wider struggle to manage waste. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/landfill-how-to-dispose-of-a-mattress-recycling-programs-1.7010678; Baxter, D. (2018, February 17). Centre does more than just recycle. Winnipeg Free Press, F5; Dacey, E. (2016, January 17). Indigenous North End business to create jobs recycling mattresses. Metro News; Martin, N. (2016, January 17). North End business to create jobs while recycling used mattresses. Winnipeg Free Press. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/North-End--business-to-create-jobs-while-recycling-used-mattresses--365586401.html; Schmidt, J. (2019, February 13). New recycling program aims to keep up to 8,000 mattresses, box springs out of Winnipeg landfills. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-mattress-mother-earth-recycling-1.5017719. ↵

- Baxter (2018). ↵

- According to Damon Johnston, president of the Aboriginal Council of Winnipeg, Mother Earth Recycling “is a huge step up for our community . . . Indigenous unemployment rates are really high” (Martin, 2016). ↵

- Quoted in Dacey (2016). ↵

- Baxter (2018). ↵

- Baxter (2018). ↵

- With slight adaption, this definition taken from page 208 in Ebert, R. J., Griffin, R. W., & Starke, F. A. (2009). Business essentials (5th Canadian ed.). Pearson. Note that this chapter has benefitted from feedback from Brianna Caza. ↵

- Because of their knowledge about an organization’s current human resources and their knowledge about available resources outside of the organization, HRM professionals should be involved in strategic decisions and have an important role to play in implementing strategic change. Ulrich, D. (1997). Human resource champions: The next agenda for adding value and delivering results. Harvard Business School Press. ↵

- Lussier, R. N., & Hendon, J. R. (2017). Human resource management: Functions, applications, and skill development. Sage. ↵

- Angwin, J., Scheiber, N., & Tobin, A. (2017, December 20). Facebook job ads raise concerns about age discrimination. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/business/facebook-job-ads.html?emc=edit_th_20171221&nl=todaysheadlines&nlid=50700384 ↵

- The questions themselves are not illegal, but they do provide prima facie evidence of discrimination that is illegal. ↵