Part 3: Organizing

10. Fundamentals of Organizing

- Learning Goals

- 10.0. Opening Case

- 10.1. Introduction

- 10.2. Fundamental 1: Ensure Work Activities are Completed in the Best Way

- 10.3. Fundamental 2: Ensure Appropriate Tasks are Assigned to Members

- 10.4. Fundamental 3: Ensure Orderly Deference Among Members

- 10.5. Fundamental 4: Ensure members work together harmoniously

- 10.6. Entrepreneurial Implications

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

This chapter describes four fundamentals of organizing and their implications for entrepreneurship, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video. This chapter marks the transition from our discussion of the planning function of management (Chapters 7–9) to examining the organizing function (Chapters 10–13).

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify the four fundamental components of organizing.

- Describe how FBL, TBL, and SET managements differ in their approaches to organizing.

- Identify the key feature of each of the four fundamentals of organizing, and how each is operationalized in FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

- Explain how entrepreneurial start-ups with few resources tend to manage the four fundamentals of organizing.

10.0. Opening Case: Organizing at Semco

When twenty-one-year-old Ricardo Semler took over his father’s company, Semco, in the early 1980s, it employed about one hundred people and generated $4 million in annual revenue.[1] Semco produced marine pumps for Brazil’s shipping industry, and at the time its organizational structures and systems were developed fully enough for the senior Semler to hand over the reins of power to his relatively young son: the company had well-designed operating standards, formal rules, detailed job descriptions, and a well-developed hierarchy and departmental structure.

Ricardo Semler, however, was not fond of the way things were organized at Semco. He had previously worked for a summer in Semco’s purchasing department and had asked himself: “How can I spend the rest of my life doing this? How can I stomach years of babysitting people to make sure they clock in on time? Why is this worth doing?”[2] He spent the next four decades implementing and refining a people-centric, radical way of organizing, which helped propel the company to unprecedented success and attracted admiration among his peers: Semler has been named business leader of the year several times in a poll of over 50,000 Brazilian executives. He has since left the position of CEO at Semco to focus on teaching other companies about his approach to organizing.[3]

When he first took over Semco, Semler threw out the books of rules and regulations that had been the result of years of standardization and formalization. Even after he helped Semco grow to over 3,000 employees and $200 million in annual revenues, its manual was still a mere twenty pages, complete with cartoons. Semler doesn’t believe in written mission statements or even in taking minutes at meetings, because once things get written down they can constrain future experimentation. Semler preferred Semco’s standards to be fluid and constantly (re)constructed by its members.

Semler also downplayed specialization at Semco: imagine working in a firm with 3,000 employees and no job descriptions. Instead, Semco instituted a “Lost in Space” program that assumes young new hires often don’t know what they want to do with their lives. The program allows them to roam through the company for a year, moving to a different unit whenever they want to. Semler himself spent little time at work—he didn’t even have his own office—preferring instead to learn and get input from a wide variety of stimuli, thereby modeling an approach that encouraged everyone to be sensitized to needs and opportunities that might otherwise be overlooked.

Semler also de-emphasized the centralization of authority. Even after Semco’s growth and diversification, it had only three levels of hierarchy. Semler himself was one of six “counselors” (top management) who took turns leading the company for six months at a time. Workers set their own salaries, set their own work hours, and chose their managers. As Semler put it: “Most of our programs [at Semco] are based on the notion of giving employees control over their own lives. In a word, we hire adults, and then we treat them like adults.”[4] Semler wanted managers to trust workers and treat them with dignity. At one point the company held a party marking ten years since the last time Semler had made a decision.

Regarding departmentalization, instead of large divisions, Semler preferred smaller, more autonomous units of 150 or fewer members where each person knows that their participation matters. The heavy emphasis on participation is consistent with Semler’s commitment to democracy, a watchword at Semco. He notes that we send our children around the world to die for democracy, but we lack democracy in our workplaces.

Semler’s embrace of a SET approach to organizing coincided with an outstanding growth rate of about 20 percent per year, and with company interests in businesses worth about $10 billion.[5] Even so, Semler was very clear that growth and profits were not his primary goals:

I can honestly say that our growth, profit, and the number of people we employ are secondary concerns. Outsiders clamor to know these things because they want to quantify our business. These are the yardsticks they turn to first. That’s one reason we’re still privately held. I don’t want Semco to be burdened with the ninety-day mindset of most stock market analysts. It would undermine our solidity and force us to dance to the tune we don’t really want to hear—a Wall Street waltz that starts each day with an opening bell and ends with the thump of the closing gavel.[6]

Profit beyond the minimum is not essential for survival. In any event, an organization doesn’t really need profit beyond what is vital for working capital and the small growth that is essential for keeping up with the customers and competition. Excess profit only creates another imbalance. To be sure, it enables the owner or CEO to commission a yacht. But then employees will wonder why they should work so the owner can buy a boat.[7]

Semler’s example demonstrates that businesses can thrive when you treat people with dignity, foster trust and participation, value experimentation and learning, and are sensitive to the larger needs and opportunities around you. For him, these are the genuine fundamentals of organizing.

10.1. Introduction

As we learned in Chapter 1, the management function of organizing ensures that tasks have been assigned and a structure of relationships created that facilitates the achievement of organizational goals. Although humankind has had a long history of organizing, many contemporary ways of organizing have only come into existence during the last century or so (Chapter 2). We live in a time when ideas like industry analyses, generic strategies, division of labor, and economies of scale are taken for granted, and we no longer marvel at the productivity and wealth that they help to create.

While it may sound simple, the idea of organizing is inherently complex.[8] It’s a bit like riding a bike. Even if you know how to ride a bike, it can still be challenging to identify the key principles that describe how to ride a bike, or how riding a bike is even possible. The same is true for organizing. Fortunately for us, Max s—one of the most influential thinkers in management and organization theory—broke down the essence of managing the organizing function into four fundamental components.[9] Managers need to ensure the following:

- Work activities are designed to be completed in the best way to accomplish the overall work of the organization. This component involves understanding the overall mission and strategy of the organization and breaking it down into smaller steps and specific activities that, taken together, can help accomplish the overall work of the organization.[10]

- The tasks assigned to members are the ones required to fulfill the overall work of the organization. This component entails taking all the specific activities that need to be performed and assigning them to specific organization members to make sure the activities are completed.[11]

- There is orderly deference among members. This component consists of ensuring that members know who makes which decisions, who assigns tasks, and who should be listened to in which situations.[12]

- Members work together harmoniously. This component pulls everything together, ensuring that the different pieces of the organizational puzzle are working together as desired.[13]

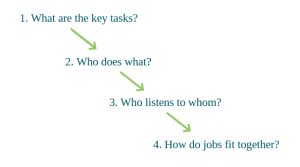

These four components can also be framed as four fundamental questions, shown in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1. Four fundamental questions of organizing

Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) management styles each have their own way of addressing these four questions. Over the past century, management scholars and practitioners have been greatly influenced by the FBL approach and its assumptions about the best way to fulfill the fundamentals of organizing. When we take for granted the assumptions and ideas that FBL management emphasizes about organizational structures, we forget how they influence us, just as we forget that we are influenced by the everyday physical structures in our everyday lives. For example, the floor plan of your home and your office shapes whom you interact with and how you interact with them (e.g., is the setting formal or informal?). The famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright once said that he could design a home that would cause newlyweds to get divorced within a few months. Along the same lines, Winston Churchill observed that “we shape our buildings, and hereafter our buildings shape us.”[14] Similarly, we design our organizational structures, and thereafter those structures shape us.

It is instructive to develop this architectural metaphor further. Architecture theory goes back at least 2,000 years to Roman times, when the three fundamentals of architecture were identified as firmness, utility, and beauty.[15] Different schools of thought or approaches to architecture will deal with these three fundamentals with different emphases, but a variation of each fundamental will be evident in each approach. For example, one approach to architecture might place a priority on keeping the financial costs of a building as low as possible. This might result in buildings that are built to last forty years (firmness), are designed to have multipurpose rooms (utility), and create a sense of beauty via minimalist design or inexpensive features like faux-marble countertops (beauty). A different approach that values ecological sustainability might result in buildings constructed out of locally available natural materials with extra insulation to last 100 years (firmness), have rooms designed to connect people to each other and to nature (utility), and whose aesthetic appeal comes from fitting into their natural and socio-cultural environment (beauty). Of course, these two approaches to architecture are not mutually exclusive, and in the final analysis all architects must take both cost and sustainability into consideration.

Just as there are clear differences in how buildings are designed and how they operate (depending on the approach of the architect), so also there are clear differences in how organizations are designed and how they operate (depending on the approach of their managers).[16] These differences are often a matter of relative emphasis. For example, as we shall see, all three approaches recognize the importance of written rules, but these receive greater emphasis in the FBL approach compared to the SET approach. Overall FBL organizing focuses on efficiency, productivity, and financial well-being. TBL seeks to optimize efficiency, productivity, and profits while seeking opportunities to reduce negative socio-ecological externalities. SET organizing is based on principles designed to enhance positive socio-ecological externalities in a way that maintains adequate levels of efficiency, productivity, and profits.

In general, FBL management focuses more on the content of organizing, on rational competencies, and on breaking things down to an individual level of analysis. In contrast, SET management places relatively more emphasis on the process of organizing, on relational competencies, and on the team and group level of analysis. SET management has a relatively fluid orientation to organizing, whereas FBL management is more static.[17] TBL management lies somewhere between the two, often leaning toward FBL management but following SET principles when doing so reduces negative socio-ecological externalities while enhancing an organization’s financial well-being.

10.2. Fundamental 1: Ensure Work Activities are Completed in the Best Way

The first fundamental of organizing involves understanding the overall work of an organization and then breaking it down into smaller tasks or steps (this can be thought of as an extension of the process of making plans described in Chapter 9). For example, even after a bike has been designed, there are many ways to organize the work of building it. The first fundamental involves identifying the best ways to bend the handlebars, to weld pieces together, to apply paint, and so on, so that in the end a well-built bike emerges.

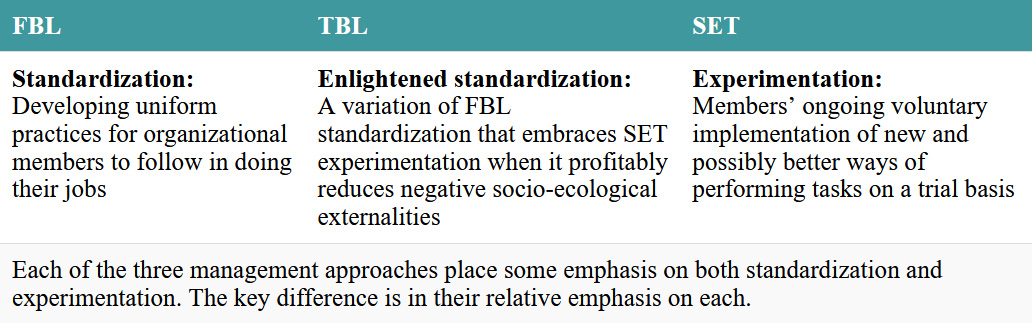

Table 10.1. Three management approaches to ensuring work activities are completed in the best way

10.2.1. Standardization

To address the first fundamental of organizing, FBL managers emphasize standardization, which refers to developing uniform practices for organizational members to follow in doing their jobs. The level of standardization in a firm can vary along a continuum from many clear standards (prescribed) to relatively few standards (non-prescribed). FBL managers focus on specifying the optimal level of standardization—such as procedures organizational members must follow when they perform their tasks—as they try to maximize organizational efficiency, productivity, and financial well-being.[18] Standardization is often related to the degree of formalization in an organization. Formalization refers to the written documentation in an organization. While formal standards are clearly important, so are informal standards that govern and give meaning to members’ behavior (e.g., see discussion of culture in Chapter 11).[19]

When we say that FBL managers emphasize standardization, it does not mean that FBL managers favor many prescribed standards (though in some cases they may). Rather, it means that managers expend a lot of effort trying to find the correct standards and level of standardization. In doing so, FBL managers sometimes develop multiple standards and at other times only a few. For example, prior to Frederick Taylor’s time and motion studies (see Chapter 2), workers who shoveled pig iron or coal into train cars would bring their own shovels from home, and every worker might have a different-sized shovel. There were no standards regarding what size of shovel was best for each task. However, after Taylor performed a series of experiments to determine what size of shovel was best for maximizing productivity for each task, the company introduced standards in line with his findings.

10.2.2. Experimentation

SET managers also use standards to addresses the first fundamental of organizing but instead of starting with standardization, SET managers tend to emphasize experimentation, which refers to members’ ongoing voluntary implementation of new and possibly better ways of performing tasks on a trial basis. SET experimentation seeks to improve socio-ecological well-being while maintaining (but not necessarily maximizing) financial well-being. SET experimentation differs from FBL standardization in several important ways. First, FBL standardization has a top-down focus (managers determine the appropriate level of standards), while SET experimentation is bottom-up (members experiment with different ways of performing tasks). Second, the FBL approach has a static nature (e.g., following tried and true standards wherever possible), while SET experimentation is more dynamic (experimentation is ongoing, constantly trying new ways of performing tasks). Third, FBL standardization tries to find the “one best way” to do things, while SET experimentation recognizes that the best way to do things is constantly changing, both inside and outside the organization. A SET approach to experimentation emphasizes the importance of discussing ideas in a group setting and benefiting from others’ input and refinement. One reason minutes were not taken during meetings at Semco is because they thought writing things down might stifle experimentation.

Lincoln Electric, founded in 1895, has become one of the most successful manufacturing companies in the world, thanks to an emphasis on experimentation that has helped it achieve significantly lower production costs than its competitors in a highly standardized context.[20] At the heart of its success are two policies built into its organization structure. One policy guarantees employment for its workers even in down times, and the other guarantees that the standard rates for piecework will not be changed simply because employee earnings are deemed to be too high. The resulting structure provides workers with plenty of incentive to increase efficiency (piecework rates will not be changed due to their improvements) and no disincentives (jobs will not be lost due to increased efficiency). Average wages at Lincoln Electric are about twice the going rate for similar work in other firms. The merit of this approach was demonstrated during World War II, when the US government asked all welding equipment manufacturers to add capacity. At that point, the CEO of Lincoln Electric went to Washington to explain that the nation’s existing capacity would be sufficient if it were used as efficiently as it was at Lincoln Electric. He then proceeded to provide proprietary knowledge about standards and techniques that would improve industry-wide productivity. When these were introduced by other manufacturers, industry output increased. For a period of time, competitors reduced their costs to about the same level as those at Lincoln, but soon Lincoln’s continuing emphasis on experimentation allowed it to once again outperform its competitors (who continued with their relative emphasis on standardization).

Of course, sometimes SET-based experiments will fail, in which case organizational members may revert back to the previous practices, but even then the organization will have gained new knowledge from the experiment. In other cases an experiment may be a rousing success, and other members of the organization can benefit from and adopt the lessons learned. For example, Semco’s “Lost in Space” program meant that lessons learned in one department traveled with employees when they moved to other departments.

TBL management’s approach to the first fundamental of organizing might be best described as enlightened standardization, which is a variation of FBL standardization that embraces SET experimentation when it profitably reduces negative socio-ecological externalities. In the business world, McDonald’s hamburgers and French fries have long been seen as examples of high FBL standardization. McDonald’s has invested a lot of resources into developing highly formalized procedures and manuals to ensure that the quality and taste of its food is consistent over time and across locations.[21] More recently, McDonald’s expanded the criteria that it uses to develop standards and now has new standards that reduce negative externalities by experimenting with ways to reduce packaging and the use of fossil fuel.[22]

Remember that the key difference between the three approaches to management is in terms of their relative emphasis. All approaches pay attention to both standardization and experimentation, but FBL managers emphasize standardization more than SET managers do, and SET managers emphasize experimentation more than FBL managers do. As we have seen, Semco has standards (e.g., do not take minutes at meetings), but the emphasis is on experimentation. Similarly, medical doctors follow standards, but doctors at a SET-oriented teaching hospital are more likely to follow them with an eye toward improving practices in the next round than are doctors in an FBL-oriented hospital that seeks to process as many patients as possible.

Test Your Knowledge

10.3. Fundamental 2: Ensure Appropriate Tasks are Assigned to Members

The second fundamental involves taking all the specific activities that need to be performed (identified in fundamental 1) and dividing them among organization members to make sure the activities are completed. The merit of giving this careful thought is illustrated by Adam Smith’s example of the division of labor in a pin factory: productivity was 1,000 times greater when workers were assigned specialized tasks rather than performing all of the different tasks necessary to make a pin (see Chapter 2).

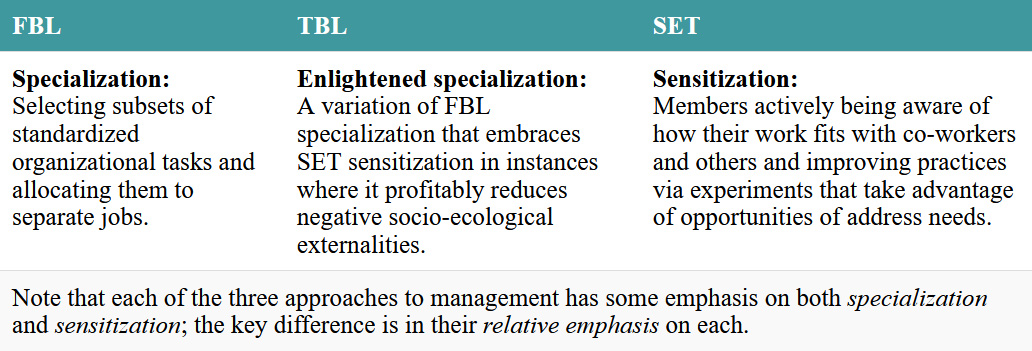

Table 10.2. Three management approaches to second fundamental of organizing: Ensuring appropriate tasks are assigned to members

10.3.1. Specialization and Sensitization

FBL management addresses the second fundamental of organizing by placing relative importance on specialization, which involves selecting subsets of standardized organizational tasks and allocating them to separate jobs. Job specialization can be narrow (which means the tasks that members perform are fairly limited and focused) or broad (which means that members perform a wide range of tasks). Specialization plays a central role in the remarkable account of how Henry Ford revolutionized productivity in the automobile industry when he pioneered the assembly line: individual members worked on one step of building a car (narrow specialization) rather than trying to assemble an entire car (broad specialization). Typically, the specialized knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) required to perform each job are spelled out in job descriptions, which also may describe the formal qualifications required for jobholders (see Chapter 12). For example, an accounting firm might require a staff accountant to pass the CPA (Chartered Professional Accountant) exam before being promoted. This is comparable to university requirements that students have certain qualifications in order to enroll in courses, such as having a high school diploma and having completed any prerequisites for the course.

SET managers also use specialization to address the second fundamental of organizing but place greater emphasis on sensitization, which refers to members’ active awareness of how their work fits with that of co-workers and others, with an eye toward improving practices via experiments that take advantage of opportunities or address needs. Just as FBL specialization helps to identify which standardized tasks should be performed by whom, so SET sensitization helps to identify what kinds of experiments should be performed by whom. Rather than focusing on ensuring that organizational members conform to specific job descriptions (specialization), the SET approach’s hallmark is to encourage members to continuously adapt to their context and improve how they do their jobs in harmony with others around them. The focus is on the dynamic process of organizing (being sensitive to new needs and opportunities) rather than on the static outcome of organizing (having the KSAOs to perform tasks listed in a job description). Sensitization includes being responsive to stakeholders’ physical, social, ecological, and spiritual needs.[23] Patagonia exemplifies this through its “4-fold” approach to making supply chain decisions, where environmental and social responsibility teams have equal decision-making power to that of traditional sourcing and quality teams. This ensures that all members are aware of both business and broader societal impacts of their decisions.

Sensitization is illustrated by how rather than assigning a desk to each of its (specialized) office workers, Semco encouraged them to move from one desk to another each week. Not even CEO Ricardo Semler had his own office. This created plentiful opportunities to get to know how the various jobs at Semco fit together, and this increased sensitization can in turn inform experimentation. It is interesting that when similar ideas (called “hot desking”) are implemented in FBL organizations for cost-saving reasons—rather than in a spirit of SET sensitization and experimentation—they are often not well-received by employees.[24]

The TBL approach to the second fundamental of organizing is enlightened specialization, which is a variation of FBL specialization that embraces SET sensitization in instances where it profitably reduces negative socio-ecological externalities. For example, TBL organizations may have “sustainability officers” whose job is to learn about different operations throughout the organization, and who also attend meetings with external sustainability-oriented stakeholders to hear about new ideas that can reduce negative socio-ecological externalities while maintaining or enhancing profits.[25] Frank O’Brien-Bernini, the first chief sustainability officer at Owens Corning, describes a two-year effort to develop a major wind farm to provide a renewable source of energy for his firm: “Whenever tensions rose with our finance team, I would remind us all of that ‘very special day’ when our ‘all-business’ controller, typically leaning back with her arms and legs crossed, suddenly leaned forward and smiled when she realized this deal actually might generate profits.”[26]

Finally, note again that the key difference between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches is in terms of relative emphasis. All management approaches pay attention to specialization and to sensitization. FBL management strives to ensure that organizations have specialists with expertise in job design and recruitment, with upper-level managers who monitor opportunities to increase profits. TBL management is similar, but in addition, middle- and upper-level managers explicitly seek opportunities to increase financial well-being by reducing negative socio-ecological externalities. SET management believes that all members should be sensitive to opportunities to enhance overall performance, and recognizes that there is need for appropriate specialization to achieve this end.

Test Your Knowledge

10.4. Fundamental 3: Ensure Orderly Deference Among Members

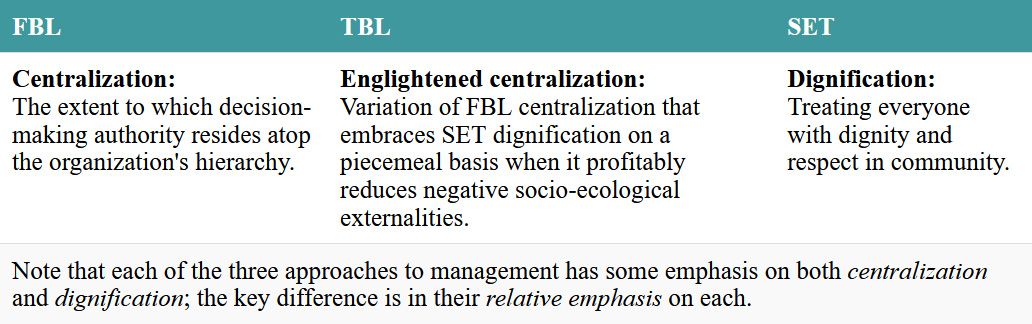

The third fundamental component of organizing draws attention to the need for members of an organization to respect and submit to one another in an orderly way. This deals with questions such as who should be listened to, how decisions are made, and how people treat one another. All three approaches to management use both centralization and dignification to address the third fundamental of organizing, but FBL management emphasizes centralization more than SET management does, and SET management emphasizes dignification more than FBL management does.

Table 10.3. Three management approaches to ensuring orderly deference among members

10.4.1. Centralization

From an FBL perspective, authority—and the degree of its centralization—is key to ensuring orderly deference among organizational members. Centralization refers to the extent to which decision-making authority resides atop the organization’s hierarchy. Authority refers to the formal power given to specific members (usually managers) to arrange resources and/or to assign tasks and direct the activities of other members in ways that help to achieve organizational goals. Organizational members are expected to defer to the people who have authority over them. Managers can use their authority to reward behavior that is consistent with organizational goals and plans, and to punish behavior that is inconsistent (Chapter 14).

An organization’s authority ranges from being concentrated to being diffused. It is concentrated, or centralized, when authority rests with top managers, and it is diffused (or decentralized) when authority is dispersed throughout an organization. An organization’s overall authority may be very concentrated (e.g., authority for most decisions is retained in the CEO’s office), while any particular subunit within that organization may be relatively diffused (e.g., what little decision-making authority that resides in, say, the finance department is dispersed widely throughout that department).[27] Organizations with diffused authority have a “flat” structure, where managers have a wide span of control, which refers to the number of members that report directly to a given manager. As described later in this chapter, AES is an example of a very flat structure when it had 40,000 employees but only three levels of hierarchy.

There are two subtypes of authority. Line authority refers to the formal power to direct and control immediate subordinates, while staff authority refers to the formal power to advise and provide technical support for others but not to tell them what to do. For example, human resource managers have staff authority to provide expert advice to managers of other departments, but they also have line authority over other members within their own department. Staff managers provide advice, and line managers make decisions.

Delegation refers to the process of giving authority to a person or group to make decisions in a specified sphere of activity. In a democracy, authority is granted to managers via citizens who elect government officials, who in turn establish the rules by which organizations are governed by their owners who in turn delegate authority to managers to act on behalf of the owners. By signing a contract to accept a job in an organization, a new member agrees to accept that managers have authority to assign them tasks to perform in exchange for payment. A similar thing happens when someone joins a voluntary organization: they agree to abide by the rules and authority structures of the organization.

When members accept authority to make decisions in a certain domain of organizational operations, they also accept responsibility for the decisions that they make (or fail to make), and they accept accountability for their actions. Responsibility refers to the obligation or duty of members to perform assigned tasks. Problems arise when someone is given responsibility without being given the required authority to meet that responsibility. Suppose a new marketing manager has the responsibility to increase sales by 10 percent. That manager will be very frustrated if they are not also given the authority to do the things that are necessary to reach the goal (e.g., to hire competent salespeople and remove incompetent salespeople). Accountability refers to the expectation that a member is able to provide compelling reasons for the decisions that they make. If a member is unable to provide a good explanation for a decision gone awry, they may be given professional training and development, have authority taken away from them, or be removed from their position.

10.4.2. Dignification

SET managers also use centralization to addresses the third fundamental of organizing but place greater emphasis on dignification, which refers to treating everyone with dignity and respect in community. Dignification assumes everyone in an organizational community has a voice that deserves to be listened to,[28] in contrast to FBL centralization, which places greater relative emphasis on listening to members in positions of authority. Whereas FBL authority-based relationships tend to be somewhat static and linear (e.g., a manager has authority over their subordinate), SET dignity-based relationships tend to be dynamic and holistic (e.g., members use their authority to enhance overall community well-being rather than merely try to maximize an organization’s financial well-being). To state this in Martin Buber’s terms, rather than set up authority structures that treat others as faceless “its” in the name of utilitarian outcomes, dignification seeks to treat others as “thous” who are listened to and respected in their own right, not merely because they have formal authority or power.[29]

As one SET CEO said about having employees make decisions: “Sometimes it’s been shown that their way is better than mine would’ve been. And even when it isn’t, just allowing them the freedom to do that [make decisions], I think, is worthwhile.”[30] People who participate in setting their own work standards are more productive and satisfied than when the identical standard is imposed on them by a manager.[31] For SET managers, creating ways of organizing that distribute dignity throughout the organization is better than developing and fine-tuning authority structures. Research suggests that when people gain status working in egalitarian organizations, versus in firms with high power differences, they are more likely to act in pro-social ways.[32]

Unlike authority, which is usually seen as a limited resource that must be parceled out sparingly, dignity is an unlimited resource that can be distributed generously; everyone has inherent worth that should be recognized.[33] Consider the dignity that was evident when Nathaniel De Avila (see opening case, Chapter 9) and Ricardo Semler gave their employees the authority to set their own salaries. According to Semler:

Arguably, Semco’s most controversial initiative is to let employees set their own salaries. Pundits are quick to bring up their dim view of human nature, on the assumption that people will obviously set their salaries much higher than feasible. It’s the same argument we hear about people setting their own work schedules in a seven-day weekend mode. The first thing that leaps to mind is that people will come as late or little as possible—this has never been our experience.[34]

Treating people with dignity also means providing them with the information they require to make decisions responsibly. Semler describes five pieces of information that help employees determine how to set an appropriate salary for themselves. Managers provide employees with (1) market surveys about what others earn who do similar work at competing organizations; (2) what everyone else in the company earns (all the way from Semler to the janitors); and (3) open discussion of the company’s profits and future prospects in order to provide a sense of whether the current market conditions allow above- or below-average salaries. The remaining two items are things that employees know but managers do not: (4) how much employees would like to be earning at this point in their career, keeping in mind how happy they are with their job and work-life balance; and (5) how much their spouses, neighbors, former schoolmates, and other significant “comparison others” are earning. Very seldom has this system been abused, perhaps because employees know that if they request too large a salary, they run the risk of annoying their colleagues and suffering the stress that comes from making a decision that they themselves know is unjust and undignified.

To meet the third fundamental of organizing (ensuring orderly deference), TBL management is characterized by enlightened centralization, which is a variation of FBL centralization that embraces SET dignification on a piecemeal basis when it profitably reduces negative socio-ecological externalities. Consider the example of Dennis Bakke, co-founder of AES, a global energy giant with 40,000 employees in thirty-one countries and annual revenues of more than $8 billion.[35] As the CEO, Bakke was committed to a SET approach, and so AES avoided written job descriptions, official organization charts, and tall hierarchies (three layers were enough). Bakke also refused to place primary emphasis on quantifiable financial goals. Instead, he argued that what he called “joy at work” can be found when the SET fundamentals of organizing are evident. For example, sensitization was facilitated at AES because performance was explicitly evaluated based on AES principles that took externalities into account and transcended economic goals. Dignification was evident because Bakke saw himself as serving his employees rather than as using his authority to command people and resources. The default at AES was to make decisions in community by members at the lowest practicable organizational level, not at the level that was deemed most efficient based on an authority structure. AES members and external stakeholders were invited to participate in AES’s decision-making process, annual reports acknowledged the contributions of ordinary employees, and people were not fired for making mistakes.

Unfortunately, at one point employees falsified the results of water testing at an AES plant in Oklahoma. Even though no ecological damage resulted from this deception, the price of AES stock dropped 40 percent on the day it released a letter that both acknowledged the falsification and recommitted itself to being an organization based on integrity. Soon Bakke’s job was on the line:

Several of our most senior people and board members raised the possibility that our [SET-based] approach to operations was a major part of the problem. It was as if the entire company were on the verge of ruin. They jumped to the conclusion that our radical decentralization, lack of organizational layers, and unorthodox operating style had caused “economic” collapse. There was, of course, no real economic collapse. Only the stock price declined. . . .

All of this put an enormous strain on the relationship between Roger [Sant, AES co-founder] and me. The board had lost confidence in me and my leadership approach. (I believe Roger had, too.) Should we split the company? Should one of us quit? He wasn’t having fun, and neither was I. I told him I wanted to stay and make the company work. . . .

The breach by our Oklahoma group was minor relative to similar missteps by dozens of large, conventionally managed organizations. There was nothing to suggest that the company operating in a more conventional [FBL] manner would have protected AES from such mistakes.[36]

What would you have advised Bakke to do? Although he and AES had been admired for emphasizing SET organizational principles, when facing the crises and economic downturns that are inevitable for any organization, he faced enormous pressure to revert to tried and true, conventional FBL methods. If Bakke had been a TBL manager, he likely would have given in to such pressures from his board. However, Bakke remained committed to SET fundamentals of organizing, and AES’s performance improved. Bakke believes that there was nothing inherent in his SET approach that would have made AES more vulnerable to missteps than if the company had followed a conventional FBL approach. In fact, a SET approach might decrease likelihood of such problems.[37]

Test Your Knowledge

10.5. Fundamental 4: Ensure members work together harmoniously

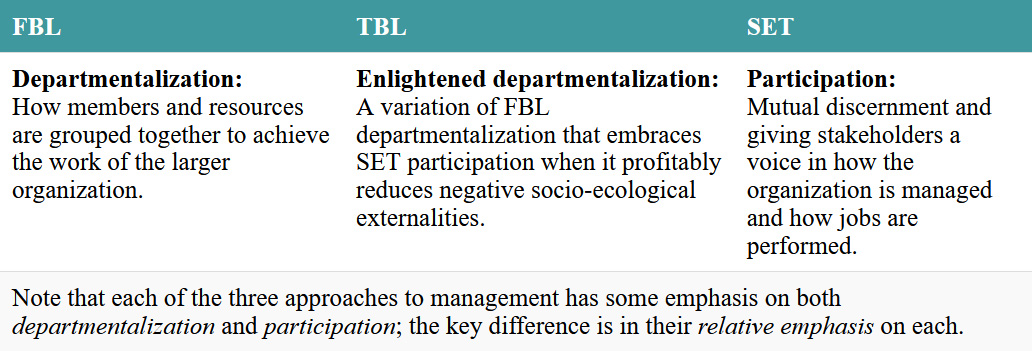

The fourth fundamental of organizing deals with how members work together. The goal is to ensure that all of the tasks performed by organizational members fit together and contribute to a larger whole. As organizations grow in size, this will mean deciding where and with whom each member performs their respective tasks. All three approaches to management use departmentalization and participation to address the fourth fundamental of organizing, but FBL managers emphasize departmentalization more than SET managers do, and SET managers emphasize participation more than FBL managers do.

Table 10.4. Three management approaches to ensuring members work together harmoniously

10.5.1. Departmentalization

Departmentalization refers to how members and resources are grouped together to achieve the work of the larger organization. Departmentalization has two key dimensions. The first is departmental focus, which has to do with the relative emphasis an organization places on internal efficiency versus on external adaptiveness. The second is departmental membership, which looks at whether membership in the department is permanent versus short-term. Departmental focus is concerned with the content of the tasks each department is assigned to perform, whereas departmental membership looks at whether members are permanent and whether they come from within the organization’s boundaries. We will look at each in turn.

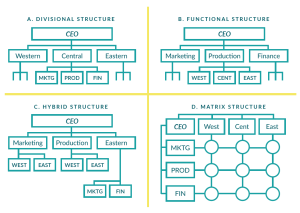

Departmental focus. The departmental focus dimension describes the basis upon which an organization is divided into smaller, more manageable subgroups. Four basic departmental structures commonly found in organizations are divisional, functional, hybrid, and matrix. A divisional structure is evident where members work together as a subunit that provides a specific kind of product or service, serves similar customers, or operates in the same geographic region. Quadrant A in Figure 10.2 shows a geographically based divisional structure with a western division, a central division, and an eastern division. A product-based divisional structure for a computer manufacturer would have a desktop division, a laptop division, and a handheld division, whereas a customer-based divisional structure might have a consumer division, a business division, and an educational institution division.[38] The key point is that each of these divisions are autonomous; that is, they operate like separate businesses or like a strategic business unit (see Chapter 8). To operate as an essentially separate business, each division needs to organize its own hierarchy around key functions like marketing, production, and finance. Divisions generally have functional departments.

Figure 10.2. Four basic types of departmental structures

A functional structure places members in the same department based on their having similar technical skills and using similar resources to perform their tasks. For example, as illustrated in Quadrant B of Figure 10.2, a furniture manufacturing firm might have marketing, production, and finance functions at the top level of the organization. Other bases of departmentalization may also be used at lower levels in the hierarchy—the production department in Quadrant B is further organized into geographically based sub-departments. And those regional sub-departments may be further organized in sub-sub-departments, based on the types of products they manufacture (e.g., chairs vs. tables vs. shelving units). In a functional structure, the top management team must coordinate the work of the various functions because none of the functional departments on their own can do all the things that are necessary to achieve corporate objectives.

The relative strengths and weaknesses of the divisional and functional structures are mirror images of each other. An automobile manufacturer that has a functional structure at the top level of the hierarchy and has just one large production department will be more efficient than a competitor with ten divisions, each with its own production department. The former company will achieve large economies of scale (i.e., the per unit financial cost to produce 10,000 cars on one assembly line is far less than the per unit cost to produce 1,000 cars on each of ten separate assembly lines). The functional approach also offers opportunities for in-depth skill development in each specialization. For example, one legal department with ten lawyers may have specialists in commercial, labor, patent, and international trade law, whereas having one lawyer in each of ten different divisions means that the lawyers will need to be generalists. A functional structure also permits increased spans of control and lower management costs, because it is easier to manage people with similar training and backgrounds (e.g., ten lawyers in one department) than for a divisional manager to manage people from a variety of functional areas.

A divisional structure offers different strengths relative to the functional structure. First, in a divisional structure, decision-making authority is closer to the organization’s customers. For example, rather than having a single production department produce all the goods for an organization, a different production department in each region or for each customer group reduces the distance between consumers and producers. This helps managers adapt to changing consumer preferences and accommodate for differences across regions or customer groups. Second, the source of profits may be somewhat unclear in a functional structure (e.g., should credit be given to vice-president of the research and development department, the production department, or the marketing department?). But in a divisional structure, each division is accountable to make a profit, so it easier to recognize the financial performance of top managers in specific divisions. Third, compared to managing a functional department, division managers who coordinate the work of members from a variety of different functional areas are likely to develop more well-rounded management skills (which may be an advantage for managers seeking to get promoted to the CEO level).

Divisional and functional structures influence how members see their organization, much like lenses shape our vision. Some lenses are designed to help us to see in the distance, while other lenses help us to see close-up. So it is with different approaches to departmentalization. Functional departments help us to see close-up within the organization. They help to maximize efficiency and to fine-tune skills and expertise in specific functional areas. Divisional departments are better at seeing far distances beyond the borders of the organization. They are more connected and attuned to the most relevant customers, and thus better able to see shifts in customer preferences, in emerging technologies, in changing government legislation, and so on. However, divisional departments are not as good at paying attention to and optimizing internal efficiencies resulting from, for example, reduced economies of scale. In some divisional structures, two different divisions can be working on the same problem and not even be aware of the unnecessary duplication of effort.

Hybrid organizations are like bifocal lenses. A hybrid structure seeks the advantages of the functional structure (by achieving internal efficiencies and developing internal expertise in some areas) and the advantages of the divisional structure (by being able to adapt to changes in a dynamic external environment). Hybrid organizations have both functions and divisions simultaneously at the same hierarchical level. Quadrant C of Figure 10.2 provides an example of a hybrid organization that has a marketing department, a finance department, and an eastern division. In this firm the eastern division, perhaps because represents the majority of an organization’s activity, has its own marketing and finance departments.

Matrix departmentalization occurs when an organization has both divisional and functional departments, and members are simultaneously assigned to both. Instead of bifocals, the matrix structure is more like having a lens for seeing close with one eye, and a lens for seeing far with the other eye. Just as such eyeglasses would take some getting used to and would probably cause some headaches as users learn to close one eye or the other as needed, so also matrix structures can be quite challenging to manage and work in. This is because, as we can see in Quadrant D of Figure 10.2, a matrix structure breaks the unity of command rule. In a matrix structure, members (represented by the circles) are responsible to two or more managers. Thus, matrix structures demand more time be spent in meetings to ensure that the amount of work being assigned to members is reasonable.[39] A matrix structure is not unlike the situation where university students are simultaneously enrolled in different courses with different professors. It can be stressful if more than one instructor coincidentally schedules an exam or report due on the same day. One of the most famous examples of a matrix structure was ABB, a global electrotechnical company, which at one time had over 200,000 employees in 150 countries who were divided into 5,000 profit centers (i.e., managers of each of these 5,000 divisions or strategic business units were expected to show a profit) and whose managers would report to both a country manager as well as to at least one of thirty-five business area managers.[40]

Departmental membership. Membership, the second dimension of departmentalization, has become increasingly relevant in the past couple of decades. Indeed, even the meaning of what it means to be a “member” of an organization has changed. Does it include part-time workers, temporary workers, people working on commission, consultants, or people hired on a one-time basis to perform a task (e.g., to copyedit a document?). As little as a generation ago it was simply assumed that an organization’s departments were composed of organizational members who had fairly permanent and well-defined individual jobs in a firm. There are still many organizations that have permanent membership, but this is changing.

Sometimes organizational members work together in teams. A team is a collection of three or more people who share task-oriented goals, work toward those goals interdependently, and are accountable to one another to achieve those goals (see Chapter 15). Recently there has been greater emphasis on having members work in task forces, which are teams that disband when their work has been completed, with members “floating” from one task force to the next as the need arises. This increased fluidity has allowed organizations to be more flexible and adaptable. For example, software programming is often done on a project basis, with specific programmers and other staff assigned to a specific project as needed. When that project is completed (e.g., the software is shipped), the programmers move to various other projects rather than all staying together and moving to work on a different project.

There are also increasing opportunities for managers to take what were once permanent jobs or departments within an organization and outsource them. Outsourcing refers to using contracts to transfer some of an organization’s recurring internal activities and decision-making rights to outsiders (e.g., see Chapter 7 on “make-or-buy” decisions). For example, a new start-up may not have the money to hire its own accountant or graphics designer; it therefore outsources these tasks to other organizations that manage the start-up’s payroll and its website homepage (recall the example of Boldr, opening case, Chapter 5). These outsourced workers are doing the work that used to be performed by permanent members. Along the same lines, a network structure is evident when an organization enters fairly stable and complex relationships with a variety of other organizations that provide essential services, including manufacturing and distribution. Nike is famous for its network structure and use of outsourcing in becoming the world’s largest athletic footwear and apparel company, with more than 1 million workers producing its products in over 500 factories, while Nike itself has less than 40,000 employees.[41] The core staff in its network structure resides in the company’s Beaverton, Oregon, headquarters and designs the prototypes. However, the actual production, transportation, and retail sale of its shoes and apparel is outsourced to overseas factories and retailers.

In a virtual organization, work is done by people who come and go on an as-needed basis and who are networked together with an information technology architecture that enables them to synchronize their activities. Virtual organizations allow for people to be hired for short (or long) periods of time, often on a contract basis, from anywhere around the world. These workers may never see each other, and they may have no ongoing commitment to the organization. They are hired to do a specific job, and when that job is completed their connection to the organization may be over. Some organizations in the so-called sharing economy—such as Uber and Airbnb—have characteristics associated with virtual organizations.

10.5.2. Participation

SET managers also use departmentalization to address the fourth fundamental of organizing. However, compared to FBL and TBL managers, SET managers place greater relative emphasis on the idea of participation, which refers to mutual decision-making that gives stakeholders a voice in how the organization is managed and how jobs are performed. SET participative structures can include permanent members and external stakeholders such as suppliers and customers, and they can span issues related to internal efficiency and external effectiveness as needed. Participative structures value stakeholders’ input on decisions, as well as their input for setting the agenda on which issues that require decisions. Compared to the SET approach, FBL and TBL approaches place relatively less emphasis on participation, both in amount and in breadth of involvement. SET management uses participative structures to complement the two generic dimensions of departmentalization (functional and divisional).

Departmental focus. All things being equal, SET management generally prefers a divisional structure rather than a functional structure. In addition, the SET approach prefers relatively small divisions (fewer than 150 members) that essentially operate as autonomous subunits, where each member has a sense of the overall goals of the unit and understands how their individual effort meshes with the efforts of others to meet those goals. This is illustrated by Semco’s division sizes of about 120 to 150 members. Once a division grows much beyond this size, it should be subdivided into two divisions.[42]

Departmental membership. SET managers are more likely to include and invite the participation of external stakeholders. Of course, these stakeholders are not members in a formal sense but members of the larger community that an organization sees itself operating within. Stakeholders can also include the natural environment more generally. Inviting, listening to, and responding to a variety of stakeholders allows the organization to be sensitized to new opportunities and also enhances goodwill when the inevitable mistakes are made. For example, Ricardo Semler describes meeting with customers, showing them Semco’s financial statements with respect to a particular sale, and listening to what the customers say. Such transparency can in turn prompt reciprocated transparency and openness, and Semler describes how Semco started whole new product lines simply by listening to its customers. This has been called “extreme stakeholder alignment,” which involves deliberately giving opportunities to employees, partners, customers, government representatives, and society to actively participate in making organizational decisions that could affect them: “Alignment is your value creation engine.”[43]

Patagonia has developed a unique network structure that extends beyond traditional business relationships to include environmental organizations, grassroots activists, and community groups. Through initiatives like 1% for the Planet, which has contributed over $161 million to environmental causes since 1985, Patagonia demonstrates how network structures can advance both business and social goals. The company’s network includes relationships with fair trade–certified factories, organic cotton farmers, and environmental advocacy groups, creating a complex web of relationships that supports its mission to “save our home planet.”[44]

SET management often avoids traditional pyramid-shaped organizational charts such as those depicted in Figure 10.2. Specifically, the SET approach is uncomfortable with representing managers at the top and subordinates underneath. SET organizations sometimes invert the organizational chart, placing customers and other stakeholders at the top and managers closer to the bottom. At other times circles are used to draw SET organization charts. For example, Semco could be depicted as three concentric circles, with the top managers in the innermost circle, middle managers in the next circle, and the remainder of the organization in the outer circle.[45] In other SET organizations, the top management team in the innermost circle might be depicted as overlapping with surrounding intersecting circles containing various organization subunits and other stakeholders, like the petals of a flower.[46]

The TBL approach can be characterized as enlightened departmentalization, which refers to a variation of FBL departmentalization coupled with some SET participation in cases where the latter enhances the organization’s financial well-being.

Test Your Knowledge

10.6. Entrepreneurial Implications

One of the most challenging things about starting a new organization is developing its structure. Some entrepreneurs address this challenge by purchasing a franchise (e.g., McDonald’s, Freshii, ReStore), where part of what is being purchased is a prescribed structure that addresses the four fundamentals of organizing. Indeed, as a condition of their franchise, entrepreneurs are often required to closely follow certain policies and structures.

In this section we describe some of the tactics and shortcuts entrepreneurs use to manage the four fundamentals of organizing when starting a new organization from scratch. Because entrepreneurs are being pulled in so many different directions, the time and resources that they can invest to establish a structure are limited. This results in underdeveloped structures that share remarkable similarities across organizations, regardless of whether the entrepreneur takes an FBL, TBL, or SET approach.

10.6.1. Fundamental 1: Standardization and Experimentation

Start-ups generally have few standards because new organizations are still figuring out and fine-tuning their goals and strategies, and because entrepreneurs generally do not have time to write policy manuals and job descriptions when they’re already working fifty or more hours each week. Instead of developing specific standards for each member of the start-up, entrepreneurs often simply use the organization’s overarching goals and strategies to (a) serve as general guidelines for members’ decision-making, (b) facilitate coordinated decision-making, and (c) motivate members by giving them an understanding and appreciation for the meaning of their work. Ensuring that members are aware of the “big picture” also helps to address one of the dangers of having too few performance standards, namely, where members spend too little time actually working and too much time trying to find out what they are supposed to be doing.

Start-ups must, of necessity, spend time on experimentation as members learn what works and what doesn’t, and as performance standards are continually (re)constructed by members and stakeholders. Experimentation helps the start-up learn more quickly than if all the learning was done only by the founding entrepreneur(s). But start-ups can have too much experimentation—this occurs when members are doing too many experiments, and the results of those experiments are not coordinated. Having a weekly meeting where everyone updates each other on their activities is a simple way to guide and focus experimentation, and to ensure that activities are being completed in the best way for the organization.

10.6.2. Fundamental 2: Specialization and Sensitization

It is generally appropriate for start-ups to have broad rather than narrow specialization. This is because new organizations are continuously fine-tuning their understanding of the specific KSAOs that they need, and because they have relatively few members to perform all the different tasks that need to be performed (e.g., one member may be both a receptionist and bookkeeper). Thus, entrepreneurs are more interested in hiring generalists (people who know something about a variety of things) than specialists (who know a lot about one thing).

Start-ups typically place relatively high emphasis on sensitization, which is evident when people are hired for being able to develop and learn from interrelationships among stakeholders, both inside and outside of the organization. Entrepreneurs value the complementary skills of a team more than the individual skill sets of particular members. SET entrepreneurs in particular appreciate members who have valuable experience or knowledge that goes beyond the financial goals of the organization. An emphasis on sensitization assumes that an organization will have multiple goals that should change as its members grow and learn from each other and from other stakeholders.[47] But start-ups can have too much sensitization, which can result in an inability to help anyone as members become too distracted by trying to help everyone. Again, this danger can be managed via weekly meetings where all members of the start-up report on their work and help each other stay focused on their key tasks.

10.6.3. Fundamental 3: Centralization and Dignification

Entrepreneurs often have very strong ideas about what should be happening in their start-up, and they can be reluctant to delegate authority to others (i.e., they are tempted to micromanage everything, often in a very autocratic way). However, they soon learn the merit in focusing their efforts on those tasks that are the most crucial for the success of the start-up and delegating authority to others to complete less essential tasks.

At the same time, entrepreneurs quickly learn that their organization will benefit if the ideas of different members are given serious consideration and if members treat each other with care and respect, which is facilitated via a free flow of information and collaboration. The danger of too little dignification is that stakeholders will treat their jobs in instrumental terms and thus be reluctant to put in the extra effort often required for start-ups to succeed. However, too much dignification may result in delays as different stakeholders are consulted. Again, weekly meetings where everyone has a voice are a simple way to facilitate orderly deference among members.

10.6.4. Fundamental 4: Departmentalization and Participation

Start-ups are more akin to a division than to a functional department, and place relatively high emphasis on participation. Because of their small size, it is possible and often desirable to treat members of a start-up as a team that is seeking to establish itself in its industry (Chapter 16). In assembling this team, it is crucial for entrepreneurs to identify the key functional competencies that must be housed in the organization and those that can be outsourced. For example, in a car dealership, sales skills are a core competency, while tax accounting skills may not be. For a tax filing company, however, accounting skills are central, while sales skills may be secondary. Can payroll be outsourced? Should transactions be handled directly, or via a service like PayPal or Shopify? These and other related decisions are important ones for entrepreneurs to make. Sometimes the identification of core competencies may not be obvious for an entrepreneurial start-up. For an example of how focusing on core competencies can be key to success, recall that the world’s largest sports apparel company, Nike, outsources its manufacturing, shipping, and retail functions. Similarly, Patagonia recognized early on that its core strengths lay in design, testing, and marketing of outdoor gear—not in manufacturing. Like Nike, Patagonia chose to outsource production while maintaining tight control over its core competencies. Even so, Patagonia was able to ensure its values were maintained throughout outsourced operations, which included applying rigorous supplier standards and its ”4-fold” approach to supplier selection (where environmental and social responsibility teams have as much decision-making power as traditional sourcing and quality teams do). This demonstrates how entrepreneurs can outsource effectively while maintaining their organizational values.

Start-ups tend to place relatively high emphasis on participation, which can help to compensate for the lack of well-developed departmentalization and facilitate everyone’s working together harmoniously. This includes giving members a voice, as for example in weekly organizational staff meetings, and also giving other outside stakeholders a voice.

In sum, regardless of whether entrepreneurs prefer an FBL, TBL, or SET approach, well-managed start-ups will tend to be characterized by (1) relatively few standards and many experiments, (2) broad skill sets and much attention to how one’s work fits with that of others, (3) diffusion of authority and dignification, and (4) a divisional orientation and participation. These characteristics will be discussed further in the next chapter, which will also provide a more in-depth discussion about the differences between FBL, TBL, and SET organization structures.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Organizing means ensuring that tasks have been assigned and a structure of relationships created that facilitates the achievement of organizational goals.

- In general, FBL management focuses more on the content of organizing, rational competencies, and breaking things down to the individual level of analysis. In contrast, the SET approach places relatively more emphasis on the process of organizing, relational competencies, and the team and group level of analysis. TBL management is a hybrid of FBL and SET approaches.

- The four fundamentals of organizing serve to ensure that (1) work activities are designed to be completed in the best way to accomplish the overall work of the organization; (2) the tasks performed by members contribute to the whole; (3) there is orderly deference among members; and (4) members work together harmoniously.

- To satisfy the first fundamental, FBL management emphasizes standardization (developing uniform practices for organizational members to follow in doing their jobs), whereas SET management favors experimentation (ongoing voluntary implementation of new ways of performing tasks on a trial basis). The TBL approach can be characterized as enlightened standardization, meaning that standardization is combined with some experimentation if doing so enhances the organization’s financial well-being.

- To satisfy the second fundamental, FBL management focuses on specialization (grouping standardized organizational tasks into separate jobs), while SET management encourages sensitization (being aware of and receptive to better ways of doing things to take advantage of existing opportunities or to address existing needs). The TBL approach can be characterized as enlightened specialization, where specialization is coupled with some sensitization if doing so enhances the organization’s financial well-being.

- To satisfy the third fundamental, FBL management prioritizes centralization (having decision-making authority rest with managers at the top of an organization’s hierarchy), whereas SET management emphasizes dignification (treating everyone with dignity and respect in community). The TBL approach can be characterized as enlightened centralization, in which centralization is combined with some dignification in instances where it enhances the organization’s financial well-being.

- To satisfy the fourth fundamental, FBL management emphasizes departmentalization (grouping members and resources together to achieve the work of the larger organization), whereas SET management prefers participation (mutual discernment and guidance). The TBL approach can be characterized as enlightened departmentalization, which refers to departmentalization coupled with some participation in cases where the latter enhances the organization’s financial well-being.

- Generally speaking, classic entrepreneurial start-ups place relatively low emphasis on standardization, specialization, centralization, and departmentalization. Instead, they place relatively high emphasis on experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Describe the four fundamental components of organizing. What are the general differences between the three management approaches (FBL, TBL, and SET) in terms of how the organizing function is carried out?

- Do you think virtual organizations will become more prevalent during your career? Why or why not?

- Do you think treating others with dignity will change (increase or decrease) the amount of power that you have? Is the effect of treating others with dignity the same for all people, regardless of how much power they have to start with? Explain.

- Review the Semco case at the start of the chapter. Should employees be trusted to set their own salaries, choose their own hours, and hire their own managers? Should university students be trusted to assign their own grades? In your view, what sort of information should instructors provide, and what should students provide, to set up a fair way for students to self-assign marks?

- Ricardo Semler writes: “I’m not preaching anti-materialism. We do, however, desperately need a better understanding of the purpose of work, and to organize the workplace and the workweek accordingly. Without it, the purpose of work degenerates to empty materialism on one side and knee-jerk profiteering on the other.”[48] Do you agree with Semler’s observations? Explain what you understand to be the purpose of work. As a manager, how might you best structure the workplace based on your understanding? How does your analysis relate to Figure 5.1: Two key dimensions related to meaning in life?

- Think of an organization you might want to start. Describe how you would manage each of the four fundamentals of organization, describing your approach to (1) standardization and experimentation, (2) specialization and sensitization (3) centralization and dignification, and (4) departmentalization and participation. Why do you think your choices are the best ones? What effect will they have on the organization?

- Imagine that you have just launched the organization described in your answer to question 6. What sorts of changes in how you manage the four fundamentals of organizing would you expect to see after five years of operations? What factors would affect the changes? Explain your answer.

- For more information on how Semco is managed, see Green, M., & McNeill, B. (2024). Redistributing power through the democratisation of organisation. In B. McDonough & J. Perry (Eds.). Sociology, Work, and Organisations (pp. 117–132). Routledge; de Souza Sant’Anna, A. (2024). Applying quantum field theory to understand emergent leadership in complex adaptive systems: A case study of Semco. Leadership Observatory NEOP FGV-EAESP. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16772.74886. The case was developed based on Kastelle, T. (2013, November 13). Hierarchy is overrated. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/11/hierarchy-is-overrated; Rees-Mogg, M. (2015, December 10; updated 2016, March 21). Business leaders: Ricardo Semler. Startups; Semco Style Institute. (2016, May). Ricardo Semler: The radical boss who proved that workplace democracy works. https://semcostyle.com/ricardo-semler-the-radical-boss-who-proved-that-workplace-democracy-works/; Semler, R. (2004). The seven-day weekend. Portfolio/Penguin Group; Semler, R. (1989, September–October). Managing without managers. Harvard Business Review, 76–84. https://hbr.org/1989/09/managing-without-managers; Vogl, A. J. (2004, May–June). The anti-CEO. Across the Board, 41(3): 30–36. This case also borrows heavily from Dyck, B., & Neubert, M. (2010). Management: Current practices and new directions. Cengage/Houghton Mifflin. ↵

- Semler (2004). ↵

- For more on what Ricardo Semler has been doing since selling Semco, please visit the Semco Style Institute website at https://semcostyle.com/ricardosemler/. After Semler sold Semco, information about its management model has been difficult to find; see page 910 in Mládková, L. (2023). Supporting knowledge communities: Examples from organisations with innovative management models. In F. Matos & A. Rosa (Eds.), Proceedings of the European Conference on Knowledge Management (Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 908–915). https://doi.org/10.34190/eckm.24.1.1137. Scholars continue to analyze Semler’s management approach at Semco: see Green & McNeill (2024); de Souza Sant’Anna (2024). ↵

- Semler (1989: 77). ↵

- Rees-Mogg (2015). ↵

- Semler (2004: 12). ↵

- Semler (2004: 92). ↵

- For recent reviews of the field, see Jerab, D., & Mabrouk, T. (2023a). How to design an effective organizational structure & the 21 century trends. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4584646, or at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4584646; Jerab, D., & Mabrouk, T. (2023b). The evolving landscape of organizational structures: A contemporary analysis. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4584643, or at http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4584643 ↵

- Weber, M. (1958). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (T. Parsons, Trans.). Scribner’s; see analysis of Weber in Dyck, B., & Schroeder, D. (2005). Management, theology and moral points of view: Towards an alternative to the conventional materialist-individualist ideal-type of management. Journal of Management Studies, 42(4): 705-735. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00516.x ↵

- Because of its focus on the organization’s overall goals and performance standards, this component can be seen as loosely related to the management function of planning. ↵

- This component may be most closely related to the first part of the organizing function, namely assigning tasks and creating organizational relationship to facilitate meeting organizational goals. ↵

- This component is somewhat related to the leading function. ↵

- This fundamental is somewhat related to the function of controlling. ↵

- This quote and the reference to Frank Lloyd Wright are taken from Orr, D. (2006). Design: Part I. Geez 3 (Summer): 8. ↵

- Kruft, H.-W. (1994). A history of architectural theory: From Vitruvius to the present. Princeton Architectural Press. ↵

- For an explicit examination of the relative emphasis that managers place on materialism and individualism, see Dyck, B., & Weber, J. M. (2006). Conventional versus radical moral agents: An exploratory empirical look at Weber’s moral-points-of-view and virtues. Organization Studies, 27(3): 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606062430. Dyck and Weber found that managers who placed more emphasis on materialism and individualism also placed more emphasis on standardization, specialization, centralization, and formalization, and less emphasis on experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation. In contrast, managers who placed less emphasis on materialism and individualism also placed less emphasis on standardization, specialization, centralization, formalization, and more emphasis on experimentation, sensitization, dignification and participation. See also Dyck, B., & Schroeder, D. (2005). Management, theology and moral points of view: Towards an alternative to the conventional materialist-individualist ideal-type of management. Journal of Management Studies, 42(4): 705–735. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00516.x ↵

- This SET emphasis on process and relational competence is consistent with Henry Mintzberg’s notion of “strategic learning” discussed in Chapter 9. The SET approach does not see a lack of formal structure as a weakness to be overcome but rather embraces it as a hallmark of an appropriate way to manage the organizing function process. ↵

- For more on standardization, see Grillo, F., Wiegmann, P. M., de Vries, H. J., Bekkers, R., Tasselli, S., Yousefi, A., & van de Kaa, G. (2024). Standardization: Research trends, current debates, and interdisciplinarity. Academy of Management Annals, 18(2): 788–830. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2023.0072 ↵

- Usually when we think of standards, we think of formal standards. The more written documentation there is, the higher the degree of formalization. This is particularly evident in very bureaucratic organizations like McDonald’s. However, informal standards are also important. For example, informal standards are evident in the university classroom when students don’t walk out in the middle of class, turn off their smartphones, ask questions by raising their hands, and so on. Such informal standards are often not formally written into course outlines because they are part of the “culture,” or informal expectations of university students and professors. In this way, part of the role of organizational culture is to provide standards for members’ behavior. Research suggests that there is a link between formalization and organizational values, showing that an increase in formalization is a barrier to trust (in individualistic countries). Huang, X., & Van de Vliert, E. (2006). Job formalization and cultural individualism as barriers to trust in management. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 6(2): 221–242. http://doi.org/10.1177/1470595806066331 ↵

- The details of Lincoln Electric in this paragraph were drawn from Carmichael, H. L., & MacLeod, W. B. (2000). Worker cooperation and the ratchet effect. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1086/209948. The description in this paragraph is drawn from Dyck & Neubert (2010). ↵

- For example, when McDonald’s opened its first branch in Moscow, it discovered that local farmers could not provide the high-quality potatoes needed to meet McDonald’s standards. So McDonald’s flew in experts, imported the appropriate seeds and harvesting machinery, and trained Russian farmers how to grow and harvest the potatoes it needed. The Russians who were hired to manage the Moscow branches were trained in Canada and at “Hamburger University” in Chicago. ↵

- Martin, D. & Schouten, J. (2012). Sustainable marketing. Prentice-Hall. ↵

- Sensitized managers who are unable to have their concerns addressed in-house may resort to whistle-blowing, or join or start more SET organizations. See Badaracco, J. L ., Jr., & Webb, A. P. (1995). Business ethics: A view from the trenches. California Management Review. 37(2): 8–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165786 ↵