Part 1: Background and Basics

1. Introduction to Management

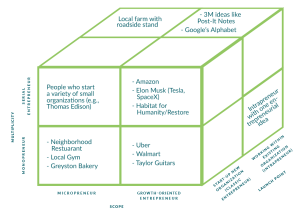

This chapter describes what management is and why it is worth learning about, and introduces readers to three approaches to management: Financial Bottom Line, Triple Bottom Line, and Social and Ecological Thought. The chapter is summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- State five reasons why the study of management is important.

- Describe Fayol’s four functions of management and Mintzberg’s ten managerial roles.

- Distinguish between the three approaches to effective management.

- Describe the benefits of studying three approaches to management.

- Identify three important reasons that people start new businesses.

- Distinguish between different types of entrepreneurs.

1.0. Opening Case: Taylor Swift’s Taylor Guitars

Taylor Swift’s 2023–2024 Eras Tour was a cultural phenomenon that further cemented the pop star’s staggering fame and groundbreaking influence.[1] Police-escorted motorcades, traffic brought to a standstill, frenzied fans flocking with no hope of venue entry, and resale tickets selling for up to the cost of four years’ college tuition prompted luminaries like Billy Joel to compare the response to Beatlemania.[2] Those lucky enough to be attend might have glimpsed the name “Taylor” emblazoned on the headstock of some of the artist’s guitars. And many may have assumed it was a custom instrument or one of Swift’s licensed branding deals, given her status as “one of the world’s most influential business leaders.”[3] In fact, the headstock emblem is the coincidental namesake of Bob Taylor of Taylor Guitars, who many years earlier was instrumental in supporting the budding teenage singer-songwriter on her improbable path to eventual superstardom.[4]

Like the Taylor Swift phenomenon, the Taylor Guitars story is a classic example of a highly successful business enterprise built from humble and uncertain beginnings. The company was founded in San Diego in 1974, when Bob and two young partners purchased a fledgling guitar-building collective fortuitously known as The American Dream.[5] Despite meager start-up resources and little business experience, Taylor Guitars has grown to be one of the most established and revered American guitar brands through decades of hard work, frugality, and dogged determination. Today the company boasts approximately 1,200 employees and over $100 million in sales.[6] Known as a quality and innovation leader, Taylor Guitars has spearheaded the application of advanced manufacturing technology (e.g., use of computer numerical control [CNC], lasers, and robotics) and numerous transformative product designs. Even more impressive, the company’s contributions to social and ecological well-being make it a standout not just among guitar manufacturers but among businesses more generally.[7] The company’s conversion to full employee ownership in 2021 was just the latest marker of its progressive practices on behalf of workers.[8]

Despite its reputation for innovation, Taylor Guitars remains a staunch traditionalist in at least one area: for fingerboards, it uses ebony wood exclusively. Ebony is an extremely dark, dense, and hard-wearing wood that has been favored by stringed-instrument builders for hundreds of years. In 2011, Bob and his team were presented an opportunity to purchase a small ebony mill in the West African country of Cameroon. During multiple trips to the country, they witnessed firsthand the desperate conditions on the ground: facilities lacking the bare necessities of running water and reliable electricity; machines in disrepair and a constant state of failure; workers paid less than Cameroon’s minimum wage without any job security; and a business environment where bribes were routinely paid to advance favors and economic interests.

One of their early, shocking discoveries was that for every marketable ebony tree harvested, loggers were cutting up to ten other trees deemed unmarketable and leaving them on the forest floor to rot. No one in the guitar industry had any idea this extreme level of waste was taking place. But once seen, it was impossible to unsee. Bob realized he faced a critical fork in the road. If he walked away from purchasing the ebony mill, it would mean he could never use ebony again. He could no longer in good conscience participate in sourcing wood from the ethically and environmentally compromised conditions he had witnessed. Bob recounts: “We decided that the only way around it was through it, and that by buying the company, [that] would be the very vehicle where it was done ethically, legally, all the rules followed . . . not just the rules of Cameroon, but the rules of the United States. . . . And then our adventure began.”[9]

1.1. Introduction

The development of Taylor Guitars from entrepreneurial start-up to established industry leader and the various factors weighing on Bob Taylor’s purchase decision in Cameroon depict the real world of management. This book is all about management, and it was written for people who want to better understand what it means to be an effective manager in today’s world. In this first chapter, we start by explaining why it is important to learn about management. We then describe what management is all about and what managers do. Next, we introduce three different approaches to management, which we will refer to continuously throughout the rest of the book. The first approach will be of interest to those who want to learn about the classic ideas related to maximizing an organization’s financial bottom line. The second approach describes the current emphasis on a triple bottom line approach, where managers seek to enhance financial well-being by reducing social and ecological costs associated with their organization’s activities. The third approach describes what management looks like when the primary organizational goal is to optimize social and ecological well-being instead of profit. In this approach, financial viability is important but not the top priority, and it does not need to be maximized. The final section of this chapter, as with every chapter in this book, highlights the implications of the chapter material for entrepreneurship theory and practice.

1.2. Why Learn About Management?

Learning about management is valuable for at least five reasons. First, it will increase your opportunities to be offered a job as a manager. Managers must develop strong technical skills—expertise in a particular area like marketing, accounting, finance, or human resources—and strong social skills—abilities in getting along with people, leadership, helping others to be motivated, communication, and conflict resolution. But technical and social skills by themselves are insufficient to get promoted into management. Rather, it is strong conceptual skills that often determine who gets promoted. Conceptual skills refers to the ability to think about complex and broad organizational issues. This is the focus of this book: to introduce and develop a solid conceptual framework of what management is all about. The book will also help you to better understand and develop relevant skills in areas like strategic management.

Second, the better you understand the nature of managerial work, the easier it will be for you to get along with the managers for whom you work. This will not only make your work experience less stressful and more enjoyable, but it should also help to make your organization run more smoothly.

Third, learning about management will help you to better understand the important role that managers play in our society. That in turn will help you deal with the various organizations you encounter on a daily basis. The knowledge provided in this book is relevant for all kinds of organizations: large or small, profit-oriented or nonprofit, local or international, traditional or virtual. It is also relevant at every level of management in organizations, including for

- first-line supervisors, who manage the work of organizational members who are involved in the actual production or creation of an organization’s products or services;

- middle managers, who manage the work of first-line supervisors and others; and

- top managers, who have organization-wide managerial responsibilities, such as chief executive officers (CEOs), vice-presidents, and board chairs.

Of course, the nature of managerial work changes depending on the level and type of organization. What a manager does may also vary depending on the size of the organization, the kind of technology it uses, its location, its culture, and so on.

Fourth, studying management can help you to improve the ability of organizations you are involved with to create and capture value. All organizations need to engage in value creation, which means offering goods and services that are valued by society, and financial value capture, which means acquiring part of the financial benefits associated with the value being created. The book will enhance your ability and knowledge to create value, especially in developing new products and services within an organization or in starting a new organization. It will also teach you different ways to think about what value capture actually means. For example, should business always seek to maximize profits and shareholder wealth, or is it sufficient to remain financially viable while enhancing opportunities to create socio-ecological value?

Finally, the study of management is important because it fosters self-understanding. By understanding management, we get a better sense of the values and forces that shape us as persons and as societies. According to prominent management philosopher and scholar Peter Drucker, management “deals with people, their values, and their personal development . . . management is deeply involved in moral concerns.”[10] Thus, one goal of this book is to help you develop a rich understanding of how different approaches to management are based upon different sets of values. This will also help you to think about contemporary issues like personal and corporate corruption, climate change, downsizing, income inequality, diversity and inclusion, and decisions to move jobs overseas.

While the goal of this book is to help you on your path to becoming an effective manager, it is important to recognize that management skills cannot be learned simply by reading a textbook or by studying in the classroom. Henry Mintzberg, an influential management thinker whom we’ll discuss later in this chapter, explains that management is neither a science nor an art but rather a practice.[11] To draw an analogy, the path to becoming a concert pianist certainly requires a solid understanding of music theory and familiarity with the mechanics of the instrument, but most important are the many hours over many years spent actually practicing the piano. Similarly, management skills are developed over many years of actually working in organizations, and effective managers continually develop and refine their skills throughout their career. You may not be ready for the CEO’s office yet, but it’s not too soon to begin practicing management in student clubs, your current workplace, or any of the other organizations you participate in (hint: student group projects can be an especially good place to practice!). Although this book alone cannot turn you into an effective manager, it will help you better understand and think about what that means. Let’s get started.

Test Your Knowledge

1.3. The Nature of Management

Because we live in a time when organizations dominate our lives, most people have at least some idea of what managers do. We generally think of a manager as “the boss” who is “in charge.” A manager has status, power, and influence. A manager gets to tell others what to do, and usually earns more money than others. Managers also have a chance to make the world a better place and to make a difference in the lives of others, both inside and outside of their specific organization. Even though managers are commonplace in our society, most people are not able to provide a clear definition of what management is. And without knowing the hallmarks of management, it is difficult to become a successful manager, a good follower, or to understand the role of management in our society.

Definitions of management commonly have two components. Management is (a) the process of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling human and other organizational resources toward (b) the effective achievement of organizational goals. The first part of the definition looks at the what of management (i.e., the four functions that managers perform), and the second part looks at the why of management (the meaning of success and effectiveness). We will look at each component in turn.

1.3.1. The What of Management: Managerial Functions and Roles

Planning, organizing, leading, and controlling are traditionally defined as the four main functions of management. These functions were first identified by Henri Fayol over a century ago and are still commonly used as the organizing framework for management courses and textbooks throughout the world.[12] These four management functions are also evident in the basic definition of an organization: An organization is a goal-directed, deliberately structured group of people working together to provide specific goods and services. Or in less technical jargon, management involves deciding what goods and services an organization will provide (planning), arranging the necessary resources (organizing) and helping people to enable this to happen (leading), and overseeing the whole process (controlling).

Although Fayol’s four functions of management continue to serve as the conceptual framework most often used to describe management, a famous study by Henry Mintzberg helps to better understand what managers actually do.[13] Mintzberg literally followed managers around for weeks and took careful notes on what they did every minute of each day. Rather than the orderly and thoughtful picture that might be implied by Fayol’s four functions, Mintzberg found that managers’ workdays are fragmented (the average time a manager spends on any activity is less than nine minutes), have a lot of variety, and move at a relentless pace. Whereas Fayol’s functions might suggest that managers spend a lot of their time at their desks, Mintzberg found that desk work accounts for only 22 percent of managers’ time.

Mintzberg’s study suggests that managers play a variety of roles in the drama that is the improv theater of organizational life. In particular, he identifies ten roles that managers play, organized into three categories:[14]

- Interpersonal roles (figurehead, leader, and liaison)

- Informational roles (monitor, disseminator, and spokesperson)

- Decisional roles (entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator, and negotiator).[15]

These categories and roles are closely integrated and follow directly from the formal authority or status a manager has, based on their responsibility for an organization or subunit.[16] That formal authority leads to interpersonal roles, which include the relationships managers have with individuals both inside and outside the organization. Interpersonal roles subsequently lead to informational roles, whereby the manager obtains and distributes the information needed to facilitate organizational work. Finally, interpersonal and informational roles culminate in decisional roles, which are critical to determining what goals the organization pursues and how it goes about trying to achieve them. Managers’ ability to choose appropriately between alternative courses of action is greatly improved when they have a deep understanding of their work.

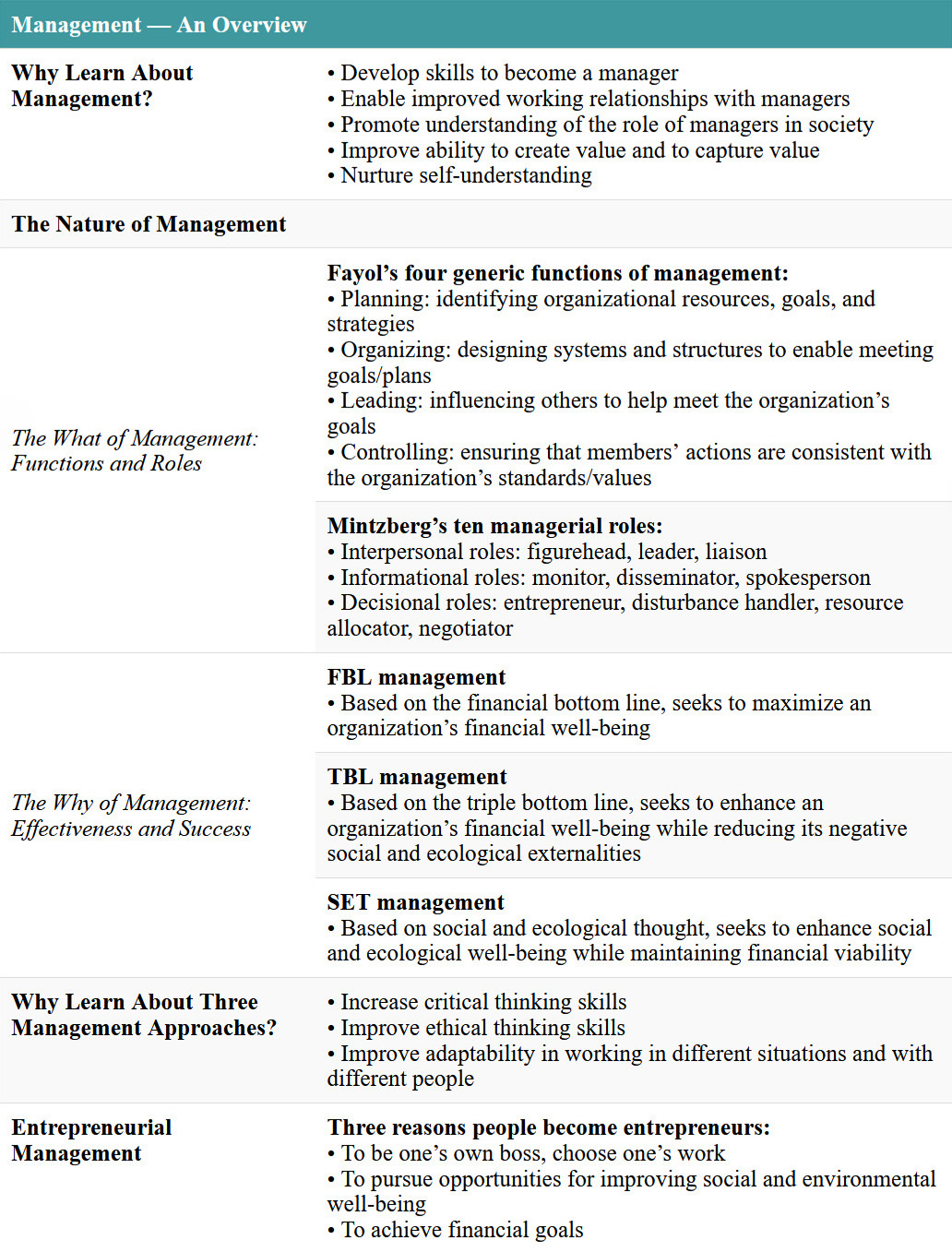

Table 1.1 provides the definitions of Fayol’s four functions and Mintzberg’s ten roles, and identifies areas of overlap between them. In the following paragraphs we describe the four functions and how each of Mintzberg’s roles can be associated with a specific function.[17]

Table 1.1. Management functions and roles

Planning

Planning means deciding on an organization’s goals and strategies, plus identifying the appropriate organizational resources that are required to achieve them. The planning function draws attention to managers’ hierarchical authority. Managers call meetings and set the agendas as to what will be discussed at those meetings. Managers ensure that departmental goals and strategies are developed, which often includes planning for the exchange of resources with key suppliers and customers. Managers are held responsible for their organizational unit’s decisions, goals, and strategies.

Mintzberg’s study suggests that planning can focus on fine-tuning a firm’s current operations, or on developing strategic organizational changes. For example, the negotiator role often involves making incremental changes to ongoing plans and resources. In this role, a manager represents the organization in major negotiations affecting the manager’s area of responsibility (e.g., negotiation of a union contract, negotiating the fee that a consulting company will be paid, negotiating the price to be paid for a new acquisition, and so on). In the disseminator role, managers transmit information to members of their own organizational unit; this information may have been gathered from internal or external sources. Such information is essential to the planning function, and includes sending memos, scheduling and attending weekly staff meetings, retelling the stories and anecdotes that represent an organization’s culture, and relaying information from top management.[18]

Perhaps the most far-reaching role in Mintzberg’s framework is the entrepreneur role, which involves proactively and voluntarily initiating, designing, or encouraging change and innovation. Managers may delegate parts of the implementation process to others but will often oversee the overall process and retain the authority to make final decisions. The entrepreneurial role, which is evident in all four managerial functions, is of growing importance in the fast-changing practitioner world, and an important part of this book.

Organizing

Organizing means ensuring that tasks have been assigned and a structure of organizational relationships has been created that facilitates meeting organizational goals. Organizing has to do with the structures and systems that managers establish and maintain. This includes developing an organization chart, which depicts the reporting relationships and authority structure of the organization, deciding on the approach to departmentalization, choosing the technology that the organization uses, the physical layout of a factory or office space, budgets, human resource policies, and so on. When senior managers are asked about the most challenging part of their job, they often talk about implementing changes to organizational structures and systems.

Two of Mintzberg’s managerial roles are most closely related to organizing. First, the resource allocator role is defined very broadly and involves the distribution of all types of resources (time, funds, equipment, human resources, and so on). Managers oversee the organizational structure that members work within, such as what sort of departments an organization has and how budgeting processes are used to allocate financial resources. Second, organizing also requires coordinating the use of resources with external stakeholders. Stakeholders are parties that have an interest in what an organization does because they contribute resources to the organization and/or are affected by its operations. This is accomplished via the liaison role, which includes building and maintaining a good structure (network) of information contacts beyond the boundaries of a manager’s specific work unit. It also includes activities like meeting with bosses and other managers at the same level within the organization, and dealing with competitors, suppliers, and customers.

Leading

Leading refers to relating with other members in the organizational unit so that their work efforts contribute to the achievement of organizational goals. Leading is often the first function that comes to mind when people think about management, because it is the most obvious and visible face of management for most subordinates. Leading includes the use of interpersonal skills in communicating with members, encouraging them, resolving interpersonal conflicts, fostering members’ motivation, and so on.

Mintzberg found that on average, managers spend 75 percent of their time interacting with people. Of particular importance is the leader role, which includes virtually all forms of communicating with subordinates, including motivating and coaching. Most of the focus of the leader role is on face-to-face interactions, and includes activities like staffing, training, and motivating. The public face of leading is often seen in the spokesperson role, where the manager transmits information and decisions up, down, and across the hierarchy, and/or to the general public. Finally, the figurehead role highlights the important symbolic function that managers play for their organizational units. Organizational members pay special attention to their manager’s behavior, taking cues from them regarding work, company values, and even personal dress codes. The figurehead role is evident when a manager hands out a plaque to honor a high-performing employee at an organizational banquet, is present at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for a new plant, or is interviewed by the media to announce a new organizational initiative.[19]

Controlling

Controlling means ensuring that an organization’s activities actually serve to accomplish its goals. Controlling can be a very visible function, such as asking members to punch in on a time clock to ensure they do not overstay their lunch hour. However, as described in subsequent chapters, the most influential controls are often less visible. These include professional norms, organizational culture, and the informal understanding employees have of “the way we do things around here” that characterizes each organization. This less visible activity of management is important because it determines the organization’s identity, shapes the identities of individual members within the organization, and provides members with meaning in their jobs.

Mintzberg’s roles draw attention to the fact that controlling includes both correcting things that are going wrong and supporting things that are going well by providing positive recognition of good work. In the monitor role, a manager seeks internal and external information about issues that can affect the organization. This might include talking to members, taking observational tours in the organization, asking questions, keeping up with the news, attending conferences to keep abreast of trends in the field, monitoring performance reports, and reading minutes from meetings. The crisis handler role requires taking corrective action when things are not going as planned. Often this includes managing unexpected difficulties (e.g., fire damage in a factory, loss of a major customer, or the breakdown of an important machine).

Test Your Knowledge

1.3.2. The Why of Management: Effectiveness and Success

The second part of the definition of management states that the four management functions are to be performed effectively.[20] There is an old expression that distinguishes between efficiency and effectiveness, where efficiency refers to doing things right and effectiveness refers to doing the right things. The idea of effectiveness points to larger, meaning-of-life, overarching goals that shape management. The question of what it means to be a good manager draws attention to the fact that managers, like anyone who makes decisions that affect other people, have moral obligations. The opening case illustrates how moral obligations impacted Bob Taylor’s decision to purchase an ebony mill. Mintzberg draws attention to this issue when he notes that “managers who can be introspective about their work are likely to be effective at their jobs.”[21]

Financial Bottom Line (FBL) Management

FBL management is characterized by its emphasis on maximizing an organization’s financial well-being, which is typically achieved by appealing to individual self-interests. For most of the past century “effective” management has been virtually interchangeable with “financially successful” management. This is particularly true when talking about business managers, where effectiveness has been measured primarily in economic terms.

Exemplary FBL Manager: Jeff Bezos

In 1994 Jeff Bezos and his then-wife MacKenzie Scott co-founded Amazon, where Bezos continues as executive chairman and is considered one of the most renowned and financially successful managers of our time.[22] Armed with a computer science degree from Princeton and leaving behind a decade of experience on Wall Street, Bezos struck out with Scott on a risky entrepreneurial venture with grand ambitions tied to the dawn of the internet age. Ambitions notwithstanding, Amazon’s austere beginnings saw Bezos selling books online from a rented garage in Bellevue, Washington, furnished with makeshift desks assembled from door slabs. The story of how, over the course of thirty years, Bezos built the global e-commerce and computing empire we know today is the stuff of management lore and wonder. Bezos’s Amazon has systematically reshaped industries, markets, and society, often against considerable odds and by bucking well-established management norms. Amazon’s growth, spread, and dominance—spanning market categories from tech to entertainment to groceries to healthcare—is unparalleled. In 2015 it became the fastest company to reach $100 billion in annual sales and in 2023 was approaching $600 billion with $30.4 billion net revenue.[23] Bezos’s personal wealth accumulation has been similarly astronomical, landing him on top of the Forbes list of world billionaires from 2018 to 2021.[24]

With respect to planning, Bezos pursued a famously unconventional strategy from the outset, one that was singularly “customer-obsessed” and coupled with an unusually long-term orientation. Consecutive financial losses over the first eight years and modest yet uneven profits through the first twenty were deemed the cost of fueling growth and securing market dominance.

On the organizing front, Bezos purposely avoided bureaucratic hierarchies and structured Amazon to encourage innovation through risk-taking along with operational excellence. The goal was to ensure that the best ideas always surfaced no matter where in the organization they originated.

Consistent with the flat organizational structure, Bezos is a notoriously hands-on and demanding leader who has been described as a micromanager. While he is equally revered and feared by those who work with him, there is near-unanimous agreement that Amazon’s success is directly tied to his unique vision and force of personality.

One of the company’s earliest and most powerful discoveries was the rich insight into consumer behavior made possible by the online retail environment. Data-driven technology platforms and processes remain the foundation of Amazon’s control systems.

FBL management is based on the idea that societal well-being is optimized when organizations maximize the creation of financial wealth, which occurs via managers maximizing organizational wealth under the assumption that individuals pursue their own financial self-interests.[25] This premise has very old roots, including the work of Adam Smith (1776) who is considered the founding father of economics. In his book The Wealth of Nations,[26] Smith introduces the metaphor of the invisible hand, which suggests that the good of the community is increased when every individual is permitted to pursue their own self-interested goals.[27] Smith’s logic is twofold. First, when individuals maximize their own financial well-being, then (regardless of whether or not they intend to) they will inevitably also maximize society’s financial well-being.[28] Second, the invisible hand will work to protect the interests of everyone; Smith argued that even rich, selfish landlords would pay their workers well, because the landlords would recognize that they were dependent on the workers who grow their food and care for their property.[29]

Not only is FBL management effective according to this economic rationality, it is also deemed to be effective and ethical according to a popularized understanding of a moral point of view called consequential utilitarianism, which focuses on optimizing an action’s rightness (and limiting its wrongness) as measured by its effect on the net overall happiness outcome for everyone involved.[30] From this view, an organization is rightly ordered when its structures and systems are arranged in a way that maximizes everyone’s net overall happiness. Because different people will have a different view of what constitutes happiness and satisfaction (e.g., some people value vacationing, others value fine food, and others value supporting charity) in practice, money is often used as a proxy for happiness (because people can use money to go on vacation, purchase fine food, or make donations to charities). Thus, in its simplified popular form, consequential utilitarianism suggests that ethical management strives to maximize a firm’s financial outcomes. Milton Friedman, recipient of the 1976 Nobel Prize in economics, can be seen as a champion of an FBL approach to effectiveness. Friedman’s views are consistent with consequential utilitarianism and with the invisible hand.[31]

The FBL approach has created unprecedented financial wealth. However, the FBL approach also is increasingly criticized for its shortcomings, because it overlooks social and ecological well-being. For example, as Amazon’s power has grown, it has faced persistent criticism regarding its labor practices and has been accused of creating excessively demanding working conditions and suppressing employees’ rights.[32] Similarly persistent are charges that Amazon acts monopolistically, illegally using its platform power to quash competition, bring dissenting vendors into line, and even invade personal privacy, with broad negative consequences for the economic and democratic health of society. The company’s environmental record is also tainted by its enormous—and potentially underreported—carbon footprint, along with highly wasteful practices tied to destruction of returned goods, packaging and plastics pollution, and increasing the materialistic appetite of a consumer society.

Overall, FBL management is facing increasing criticism because it is associated with (unintentionally) creating negative ecological and social externalities. Externalities refer to positive and negative effects that organizations have on society that are not reflected in their financial statements. For example, because current accounting practices report only activities internal to a firm’s boundaries (but not external to them), FBL profit-maximizing firms are incentivized to create negative social externalities (e.g., to keep their costs low, firms may pay less than a living wage, thereby creating expenses for others in society to cover the difference) and to create negative ecological externalities (e.g., they use the lowest-price energy sources that minimize the firm’s costs but emit greenhouse gases [GHGs] that create external costs related to climate change that others will need to pay). For example, the International Monetary Fund estimated that the externalities associated with fossil fuel use amounted to about $5 trillion in 2022, over 80 percent of which came from business.[33] In other words, business generates $1,000 worth of ecological damage per year for every person on the planet, which is about the same amount of money that the poorest half of the world lives on each year.[34]

Recall that FBL is based on the “invisible hand” assumption that increasing financial well-being at the individual or organizational level will inevitably create positive externalities that enhance overall societal well-being. And indeed, countries whose businesses have the most effective FBL managers and businesses also tend to have a high GDP (gross domestic product, which measures the total financial value of all the goods and services produced within a country) and good standard of living. However, as we shall see in later chapters, those same high-income countries also tend to deplete more than their share of environmental resources, and their inhabitants are living far beyond the carrying capacity of the planet, which is contributing to negative externalities related to climate change and the deterioration of ecological resources. Moreover, the financial benefits of large businesses that create negative externalities are not spread evenly across the globe; it is only the relatively wealthy who can afford to own shares in them. This contributes to the widening gap between rich and poor and related social problems. Observations such these have led to the development and adoption of approaches to management that seek to improve the triple bottom line.

Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Management

TBL management is characterized by its emphasis on enhancing an organization’s financial well-being while simultaneously reducing its negative socio-ecological externalities. The TBL approach is based on the assumption that managers can find win-win-win solutions that simultaneously benefit profits, people, and the planet.[35] TBL management pursues sustainable development, which means “meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.”[36] From a TBL perspective, sustainable development means simultaneously pursuing economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental quality.[37]

Exemplary TBL Manager: Jeff Bezos

In 2019, with Amazon firmly established as an exceptional model of FBL success, Jeff Bezos reoriented the company toward a broader corporate agenda in line with TBL goals.[38] On August 19 of that year, Bezos (along with 180 other CEOs of leading American organizations) endorsed the Business Roundtable’s revised Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation, including a fundamental commitment to serve a broad set of stakeholders and the natural environment rather than a narrow group of shareholders[39] (see Chapter 2). At an invited press gathering exactly one month later, Bezos described Earth as the “best planet in the solar system” and expressed full acceptance of climate science and a deep concern for the alarming state of Earth’s climate trajectory. He simultaneously announced the founding of The Climate Pledge,[40] an ambitious and collaborative Amazon-led initiative for corporations to accept responsibility and act to better the planet. In 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bezos followed up personally by committing $10 billion of his own money to “address climate and nature within the current decade” through the establishment of the Bezos Earth Fund.[41]

Under The Climate Pledge framework, planning is directed by a top-line commitment to be net-zero (carbon neutral) by 2040, ten years ahead of the international target set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement. To meet this goal, Amazon announced it would move to 100 percent renewable energy by 2030 and ordered 100,000 delivery vans from the electric vehicle start-up Rivian.[42]

Under the direction of Amazon’s central sustainability team, social and environmental efforts are organized to comprehensively address all aspects of the company’s operations in five focus areas: (1) climate solutions, (2) waste & packaging, (3) natural resources, (4) human rights, and (5) products and services. Externally oriented organizing activities involve collaborations and partnerships with a broad spectrum of stakeholder organizations spanning the private, public, and nonprofit sectors.

The Climate Pledge also represents a concerted effort to establish Amazon’s leadership in corporate sustainability (early signatories included Verizon, Microsoft, Unilever, and Coca-Cola).[43] The company’s recently launched Amazon Sustainability Exchange is another leadership exercise designed to share best practices and knowledge resources with suppliers.

As with other TBL frameworks, controlling is achieved through a systematic process of target setting, measuring, and public reporting in line with third-party standards such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and the United Nations Guiding Principles Reporting Framework. Regular reporting of GHG emissions is one of three primary Climate Pledge commitments, and true to form, Amazon has built a sophisticated carbon accounting system on the Amazon Web Services platform.

TBL management recognizes that the classic FBL approach ignores negative socio-ecological externalities created by business. In contrast, the TBL approach maintains that by attending to and reducing these negative externalities, organizations can actually further enhance their financial well-being. In short, the TBL approach draws attention to the business case for sustainable development. A business case is a justification, often documented, that shows how a proposed new organizational initiative will enhance the organization’s financial bottom line. Often a business case also demonstrates that the financial resources invested in the new initiative will yield higher returns than if they were invested elsewhere.[44] Walmart has become a leading example of TBL management by showing, for example, how decreasing the packaging of the products it sells can save money and the environment, and how LED lighting and solar panels can reduce energy costs and fossil fuel GHG emissions. TBL management is particularly popular among businesses in the Silicon Valley, which are known for providing free organic meals at their cafeterias to increase employees’ health, job satisfaction, and productivity, and thus reduce costs associated with sick days and turnover.

The TBL approach has arguably become the dominant management paradigm among large businesses. Today over 14,000 businesses in over 100 countries report according to the standards of the Global Reporting Initiative[45]—the international benchmark for sustainability reporting—which grew out of the work of the environmental nonprofit organization Ceres (Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies). Formed in 1989 in the wake of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, Ceres members include fifty of the largest and most influential global corporations, including Amazon, Apple, Coca-Cola, Ford, PayPal, and Starbucks. Consistent with a TBL orientation, their primary emphasis is on the financial rewards and investment opportunities that come from attending to social and environmental issues. They claim that “our powerful networks of investors and companies are proving that sustainability is the bottom line.”[46]

A significant shift at present is the move from voluntary reporting and participation in networks such as Ceres to legally mandated requirements for businesses to account for and report on their social and environmental performance. As of 2025, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive dictates that companies in the European Union report on social and environmental risks, opportunities, and impacts, and have those reports independently audited by a third party.[47] Similarly, new sustainability standards issued in 2023 by the International Sustainability Standards Board are being evaluated by numerous countries around the world, with anticipation that mandatory ESG (economic, social, and governance) reporting is on the horizon.[48] ESG reporting is now the dominant trend in the areas of investing, finance, and accounting, and is emblematic of TBL thinking.[49]

Finally, in terms of what it means to be a “good” manager, when compared to the FBL approach, TBL management can be seen as more effective according to both organizational economic rationality and consequential utilitarianism. First, just as FBL management can be seen to be effective because it enhances a firm’s financial well-being, the same can be said for TBL management. Indeed, research suggests that TBL firms often financially outperform FBL firms.[50] Second, the TBL approach is also arguably more ethically effective than the FBL approach within a moral point of view called enlightened consequential utilitarianism, which suggests that ethical management seeks to improve an organization’s financial well-being, especially via reducing negative social and ecological externalities.[51] This enlightened TBL approach is similar to the FBL approach, except that the TBL approach explicitly notes that reducing negative externalities can be in one’s self-interest; pursuing sustainable development and reducing negative socio-ecological externalities can serve the financial self-interests of the firm.

Social and Ecological Thought (SET) Management

SET management is characterized by its emphasis on enhancing social and ecological well-being while maintaining financial viability. SET management recognizes the importance of financial viability, but it encourages managers to improve social and ecological well-being even when this does not maximize the financial well-being of the organization. In other words, the SET approach realizes that management involves a larger “set” or collection of factors that go beyond maximizing the financial bottom line, and that management is “set” or embedded within larger social and ecological environments. The SET approach prepares managers to be ready and set to face the socio-ecological issues facing humankind. SET management is also more process-oriented than either FBL or TBL; this is consistent with the historical roots of “set” in the Old French word sette, which means “sequence” (e.g., a musical set played by a band) and points to process.[52] SET management principles are evident at Taylor Guitars (the opening case) and at Greyston Bakery, co-founded by Bernie Glassman, a former aeronautical engineer with a PhD in applied mathematics.

Exemplary SET Manager: Bernie Glassman

In 1982 Bernie Glassman and his wife started Greyston Bakery in New York City, a company that illustrates a SET approach to the four management functions.[53] Today the bakery, located on the Hudson River, is famous for the 35,000 pounds of brownies made with fair-trade ingredients it produces daily,[54] most of which end up in Ben & Jerry’s ice cream or sold at Whole Foods.

First, in terms of planning, the mission of Greyston is reflected in its motto: “We don’t hire people to bake brownies; we bake brownies to hire people.” Greyston hires chronically underemployed people such as ex-convicts and homeless people, using what it calls an open hiring process, where people apply for jobs by adding their names and contact information to a waiting list and are offered a job when it’s their turn. No resumes or references are required. In this way, over the years Greyston has created over 3,500 jobs with $65 million in salaries paid in the community. Greyston currently employs approximately 120 workers, including eighty open hires.[55]

Second, in terms of organizing its resources, all the profits from the bakery go to the Greyston Foundation, a nonprofit organization that invests in the local community. Greyston has created space for community gardens, workforce development programs that provide skills training and job placement services for youth aged eighteen to twenty-four, a learning center for children, and environmental education programs.

Third, in terms of leading, Glassman’s approach is based on two core principles: (1) life is intrinsically interdependent, which means that all businesses should help meet the needs of the whole community and the whole person; and (2) change is constant, which gives rise to seeing business as a path where one never arrives, a journey where managers value innovation, agility, and growth.[56] For example, new hires at Greyston enter a ten-month apprenticeship process during which they learn to grow as employees and as persons. In addition to the benefits this provides to participants, Greyston estimates it “generates almost $7 million per year of local economic impact through public assistance savings, increased tax revenue and reduced incarceration costs.”[57]

Fourth, with regard to controlling, in 2014 Greyston became the first company in New York to register as a benefit corporation, a new legal status now available in most US states that enables firms to place socio-ecological well-being ahead of maximizing profits. As a B Corp, Greyston uses services provided by a nonprofit organization called B Lab to monitor, measure, and certify its financial, social, and ecological performance.[58]

Just as TBL management seeks to address shortcomings associated with its FBL forerunner, so also SET management seeks to address shortcomings associated with the TBL approach. Proponents of SET management are skeptical that the TBL approach can adequately address socio-ecological problems caused by business. While it is heartening that many of the world’s largest firms are leaders in TBL practices, in 2018 the world’s 1,200 largest corporations also created about $5 trillion dollars of negative ecological externalities, an amount 50 percent greater than five years before and an amount greater than their combined profits.[59] Observations like these raise the question of whether even the best practices associated with the TBL approach are good enough. For example, Walmart’s TBL approach has had impressive accomplishments in the areas of renewable solar energy and reduced packaging, but the retailer also puts pressure on suppliers to constantly reduce prices, which creates incentives to cut corners, which in turn can reduce social and ecological well-being. As well, Walmart’s past policies on minimizing employee benefits (e.g., by keeping employees at a part-time level) off-loads costs onto social agencies and taxpayers, and its sourcing of products from around the planet creates negative externalities caused by GHG emissions related to shipping (not to mention negative socio-ecological externalities in overseas manufacturing facilities).[60]

In short, because TBL management is committed to improving financial well-being, it can address only the subset of socio-ecological problems that lend themselves to enhancing an organization’s financial bottom line. Thus, TBL businesses are unable to address the host of socio-ecological problems that cannot be solved within a profit-maximizing approach to management. It has even been argued that because business-case logic privileges financial outcomes, the TBL approach can be detrimental to the social and environmental goals it purports to uphold.[61]

Another difference between SET management and a TBL approach is that, while both emphasize reducing negative socio-ecological externalities, the SET approach places relatively more emphasis on enhancing or creating positive socio-ecological externalities. For example, after purchasing the ebony mill in Cameroon, Bob Taylor implemented immediate measures to stop the enormous waste of streaked ebony trees (reducing environmental harm) and is simultaneously finding alternative uses for the wood and launched other initiatives that ensure local communities retain the economic value of their natural resources and production (increasing social good). Greyston Bakery hires ex-convicts and others who have a difficult time finding jobs in the economy (increasing social good) and lowers recidivism and crime rates (reducing social harm).

With respect to effectiveness as defined by economic rationality, SET management is seen as less effective than the FBL and TBL approaches to maximizing a firm’s financial well-being, at least in the medium to short term. However, if we accept the argument that the FBL and TBL approaches are not sustainable in the long term, then SET management could be seen as more economically effective than the FBL and TBL approaches in the long run.[62] Along these lines, while a TBL approach to ESG has been found to increase financial performance in some studies, there are concerns that such ESG reporting and related activities have had little positive impact on meaningful social and environmental outcomes.[63]

The effectiveness of SET management in terms of ethics also differs from the FBL and TBL approaches. Recall that the FBL and TBL approaches are both based on variations of a consequential utilitarian moral point of view, which focuses on outcomes (i.e., consequences) and the idea that more financial wealth is better (more ethical). In contrast, SET management is based on virtue ethics, which focuses on how happiness is achieved by practicing virtues in community.[64] The SET approach emphasizes virtuous process and character, not financial outcomes. Indeed, virtue ethics deems it unethical to maximize economic goals for their own sake.[65] When it comes to financial well-being, virtue ethics emphasizes that “enough is enough.” This applies to having enough consumer goods as well as to creating enough financial value capture (e.g., profits). Thus, a SET approach stands in contrast to the insatiable “more money is better” assumptions that are evident in the FBL and TBL approaches. From a virtue ethics perspective, the purpose of business is not to make as much money as possible but rather to provide goods and services that benefit society.

Virtue ethics goes back to ancient Greece and to philosophers like Aristotle and his peers, who argued that using money simply to make more money and achieving luxurious amounts of financial wealth is dysfunctional and unethical. Rather, from the perspective of virtue ethics, the purpose of human activity is to optimize people’s happiness, which is achieved by practicing virtues in community. In terms of the four cardinal virtues, the virtue of wisdom is evident when managers make decisions that are deliberately aware of and informed by their larger socio-ecological setting; justice is evident when managers ensure that all stakeholders associated with a product or service receive their due and are treated fairly (being especially sensitive to the marginalized); self-control is evident when managers temper their own narrow self-interests; and courage is evident when managers are willing to address shortcomings of dominant socio-economic structures and systems.[66]

The SET management emphasis on community is also consistent with time-honored moral points of view associated with the Indigenous peoples of the planet, such as North American Cree and Ojibway, Australian Aboriginals, and the African Ubuntu philosophy, whose heritage stretches back thousands of years to the Egyptian idea of maat (which was associated with the Hebrew idea of shalom, or wholeness). Like other Indigenous moral philosophies,[67] Ubuntu has a lot to do with interconnectedness, especially people’s interconnectedness with each other and with nature. Whereas from a traditional Western perspective people see themselves primarily as individuals and secondarily as members of a larger community and cosmos, from an Ubuntu perspective we are primarily members of a larger cosmos and community who secondarily see ourselves as individuals: “I am, because we are; and since we are, therefore I am.”[68]

In sum, principles associated with SET management have been evident for a long time in the history of humankind, and the influence of SET management can be expected to grow, especially as people become more aware of the shortcomings and critiques of both FBL and TBL management approaches.[69]

Depicting Differences Between FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches

This following chapters of this book will examine in detail the differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to management. For now, we will offer two simple ways the differences can be depicted in terms of how each approach understands the relationships between financial, social, and ecological well-being. First, as shown in the Venn diagram in Figure 1.1,[70] the FBL approach tends to assume that management is primarily concerned with economic activity, which is why that circle is the largest in the figure. From an FBL perspective, the focus of management on economic activity is separate and independent from natural and social environments—this approach assumes that government and other societal institutions will manage social and ecological well-being. A TBL management approach suggests that economic activity is interdependent with the natural and social environments. TBL managers therefore seek to simultaneously improve financial, ecological, and social well-being. However, the areas of overlap are limited because TBL managers are constrained by needing to make a business case for which socio-ecological issues they can address. Finally, a SET management approach holds that economic activity is embedded within and dependent upon social and ecological well-being. Specifically, economic activities are understood to be a human invention and thus a subset of society, and society is in turn a subset of the natural environment. Just as the planet existed for billions of years before humankind came on the scene, so also humankind existed for thousands of years before money was invented.

Figure 1.1. Relationship between financial, ecological, and social realms under the three management approaches

A second way to understand the differences between the three management approaches is shown in Figure 1.2. The bar chart provides a simplified depiction of the performance level for each management approach in terms of overall financial, ecological, and social well-being. The values on the chart are intended to be suggestive and represent an average relative performance within each approach; there will be exceptions to these representations. Under FBL management, financial well-being is high, but social and ecological well-being are unsustainably low. With TBL management, financial performance is even higher, and social and ecological well-being have improved, thanks to the reduction of negative socio-ecological externalities, though they are still unsustainably low. Finally, under SET management, financial well-being is viable but lower than for the FBL and TBL approaches. However, social and ecological well-being have increased and become sustainable, thanks to a reduction of negative externalities and an increase in positive externalities.

Figure 1.2. Financial, social, and ecological performance associated with the three management approaches

Test Your Knowledge

1.3.3. Why Learn About Three Management Approaches?

You may be wondering why this text presents three different approaches to management. Why not just pick the best approach and teach it? It’s a fair question. Most management texts present a relatively singular view, typically reflecting an FBL perspective (though increasingly supplemented with TBL content). But, as will be elaborated below, understanding multiple approaches fosters adaptability and improves critical and ethical thinking. Also, as the cases already introduced illustrate, there is no universal agreement on what constitutes “best” when it comes to management. Finally, research suggests that contemporary management students align themselves with all three approaches, although after learning about the SET approach they are more likely to align with that than with the FBL or TBL approaches.[71]

Each of the three approaches to management discussed in this book represents what Max Weber calls an “ideal type.” This does not mean that they are the ideal or best way of managing. Rather, an ideal type of management refers to a specified constellation of concepts and theory that collectively identifies what effective management means and how it is practiced. Just as with other ideal types that you may be familiar with—for example, introverts versus extroverts—we would not expect to find many managers who are a perfect model of an FBL, TBL, or SET approach. This means that even though this book will provide many instances of managers who illustrate FBL, TBL, or SET management, those same managers could sometimes be used to illustrate one of the other two approaches. For example, as highlighted above, Jeff Bezos has transitioned from a predominantly FBL approach to a TBL orientation over the course of his career.

Research points to several benefits that come from learning more than one approach to management, that is, from learning about different ideal types of management. First, doing so increases critical thinking skills.[72] This is an important point, since research suggests that the critical thinking skills of university students often fail to improve even after four years of study, and that business students’ critical thinking skills sometimes lag behind those of students in other disciplines.[73] Learning multiple approaches to management helps students to develop their ability to resist simple answers by exploring and integrating opposing ideas or viewpoints, which is a hallmark of outstanding managers.[74] Learning multiple approaches can help go beyond management training (learning what managers do), and instead achieve management education (understanding why managers do what they do), so that students will be prepared to adapt appropriately to the conditions they will face in the future.[75]

Second, research suggests that learning about multiple approaches also improves skills in ethical thinking and serves as an ongoing reminder that managers’ actions and practices are not value neutral.[76] In fact, it is impossible to develop management theory that is not based on some values. Each of the three approaches to management discussed in this book is value laden (i.e., each is based on its own distinct moral point of view). Studying only one approach often acts as a self-fulfilling prophecy, where students forget that the approach is based on specific values and thus increasingly adopt those values.[77] Business schools that teach only FBL management have been criticized because their students become more materialistic and individualistic during their program of study. In contrast, learning multiple approaches compels and enables students to give careful thought regarding their own personal moral point of view and how it is expressed in the workplace. You may feel drawn to any one of the three types described here, or you may find yourself using the tools provided in this book to develop your own distinct approach to management, based on your own values and understanding of managerial effectiveness.

Finally, studying the three different approaches to management improves the ability to adapt to different situations and work with different people. It can be likened to studying three managerial languages.[78] It is important for managers to become familiar with multiple languages, because they will be managing a variety of people in a variety of settings during their careers. Students who are multilingual tend to have higher levels of cultural empathy, open-mindedness, tolerance for ambiguity and creativity,[79] a deeper understanding of their mother tongue, and an enhanced ability to learn and understand additional languages.[80] The ability to adapt and shift direction is especially important during periods of more intensive change and instability (the kind characterized by COVID-19, climate change, and escalating political tensions). Adaptability is also an essential ingredient in entrepreneurial activities, which involve developing new business solutions to real-world problems and challenges.

Test Your Knowledge

1.4. Entrepreneurial Management

Each chapter in this book ends with a discussion about the implications of the chapter material for entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs and the organizations they create are vitally important to the world. An entrepreneur is someone who conceives of new or improved goods or services and exhibits the initiative to develop that idea by making plans and mobilizing the necessary resources to convert the idea into reality. Entrepreneurs can implement changes within existing organizations and create entirely new ones, potentially fostering whole new industries and ways of doing things. Entrepreneurs have provided many of the breakthroughs and conveniences that shape our lives, and needed solutions to current problems facing the world will also be generated by entrepreneurs. A 2023–2024 report shows that in the United States, entrepreneurial activity and intentions are highest among eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds, and that sustainability is a key priority for this group.[81]

The recipe for entrepreneurial success has two main ingredients: (1) an opportunity for a new product or service that creates value for society; and (2) an organizational plan that identifies and facilitates assembling the necessary resources to pursue the opportunity. The first part of this book (especially Chapters 3, 4 and 5) will help you to explore and develop the first ingredient (that is, identifying opportunities to create value), while the remainder of the book will help with the second (establishing an organization).

In addition to these two ingredients, entrepreneurship requires a third factor: a motivated entrepreneur who acts like a chef in choosing and assembling the ingredients. Just as a chef can make an almost infinite variety of food dishes, so entrepreneurs can create an almost infinite variety of new organizational start-ups. And just as a chef is informed by their taste and the purpose and style of the meal (is it lunch, dessert, fusion?), so also entrepreneurs are influenced by their experiences and motivations.

1.4.1. Three Reasons Why People Become Entrepreneurs

A 2015 study based on the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, which provides the best international dataset available for studying entrepreneurship) found that three main reasons motivate entrepreneurs to start a new business. These reasons are directly relevant to our discussion of the FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to management.[82] First, according to the entrepreneurs in this study, perhaps unexpectedly, financial gain is only the third-most important reason for starting a new business. Although many people might assume that the main reason entrepreneurs go into business is to make money, the data suggest that this simply is not true. When entrepreneurs were asked to list all of the reasons they could think of for starting their business, less than half (42 percent) even mentioned needing or wanting more income, and only 25 percent indicated that having great wealth or very high income was important to them.[83] These results are consistent with other research findings that show that when asked to identify their primary motivation for starting a business, only 8 percent of entrepreneurs mention money.[84] So even though most management and entrepreneurship research and writing may still assume an FBL approach,[85] most entrepreneurs do not even mention financial well-being as a reason for starting a business.[86]

If not money, then what is important? The top reason entrepreneurs identify for starting their business is related to their desire for autonomy and better work (which are central components of personal social well-being, related to TBL management). For example, 73 percent of entrepreneurs rated “To have considerable freedom to adapt my own approach to work” as important.[87] This desire for autonomy and the chance to be one’s own boss is also identified as a main reason in other studies of entrepreneurs,[88] and is clearly of considerable relevance for a book on management. In order to be your own boss and to effectively manage a business in a way that is consistent with your own approach to work, it is clearly helpful to learn about different approaches to management.[89]

The second-most important reason entrepreneurs identify for starting their new business is to address challenges and pursue opportunities that are related to a SET approach. For example, 40 percent of entrepreneurs mentioned the desire “To make a positive difference to my community, to others, or to the environment.”[90] The latest GEM research confirms that entrepreneurs around the world and regardless of income level systematically prioritize social and environmental well-being above economic performance.[91] Start-ups created by entrepreneurs with this motivation and/or the motivation for autonomy and good work, have higher survival rates than financially motivated firms.

Finally, note that the reasons given above are the three main motivations for entrepreneurs who have started traditional businesses. The study does not include founders of nonprofit organizations or other social enterprises, which are entrepreneurial organizations created intentionally and specifically to pursue a social or environmental well-being mission. Thus, if such SET-oriented entrepreneurs had been included, we might expect financial well-being to be even less important and enhancing socio-ecological well-being to be more important.

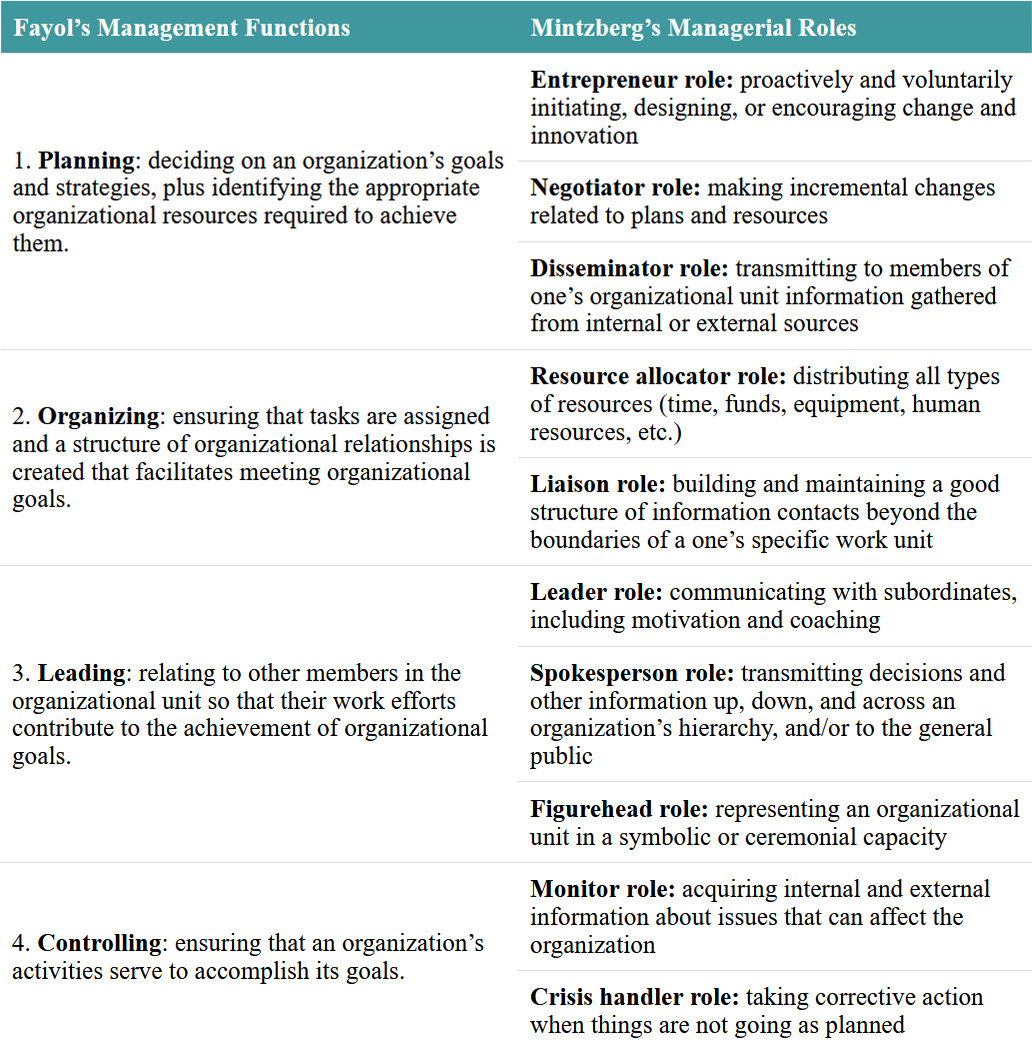

1.4.2. Types of Entrepreneurs

In addition to identifying the three main motivations of entrepreneurs, the literature also points to three important characteristics that are helpful for distinguishing between different types of entrepreneurs: (1) the scope of their ambition; (2) their propensity to start multiple new organizations; and (3) and their desire to work within existing organizations (see Figure 1.3). Each of these three characteristics is discussed below to identify different types of entrepreneurs and to explain how each type is evident in the three management approaches (FBL, TBL, and SET).

Figure 1.3. Different types of entrepreneurship

Scope

Some entrepreneurs, called growth-oriented entrepreneurs, are distinguished by a strong and clear intention to grow a new organization into a large and influential force in their industry. Examples of successful growth-oriented entrepreneurial organizations include Amazon, Facebook, Tesla, Google, and Habitat for Humanity. These and other similar organizations started in the minds of one or a few people and grew to become global giants. Because growth-oriented entrepreneurs create and capture so much value, they attract media attention and tend to be what many people imagine when thinking about entrepreneurship.

However, entrepreneurs with less ambitious goals are more common.[92] Micropreneurs seek to develop successful and viable organizations but not large ones; they do not include size in their definition of success. Many micropreneurs start their organizations for personal satisfaction or lifestyle reasons rather than to dominate an industry. Recent research suggests that entrepreneurs who seek to scale up quickly provide fewer jobs for the local economy than place-based entrepreneurs who seek to scale deep (e.g., who work with stakeholders to become more sustainable).[93] Micropreneurial organizations include local mom & pop stores, craft-oriented businesses such as microbreweries, and the many small manufacturing operations that support families in low-income economies. One common approach to becoming a micropreneur is to purchase a franchise. Franchising involves a franchisor selling a franchisee a complete package to set up an organization, including such things as using its trademark and trade name, its products and services, its ingredients, its technology and machinery, as well as its management and standard operating systems. Many well-known multiple outlet businesses are franchises, including McDonald’s, 7-Eleven, UPS, Lululemon, and Freshii.

In this discussion, scope or ambition refers to how large the entrepreneur intends for the new organization to grow; it does not refer to which of the three management approaches is used. In fact, entrepreneurs of any scope or ambition level may adopt an FBL, TBL, or SET management approach. Because many of the highest profile growth-oriented entrepreneurs appear to be primarily driven by financial profit,[94] one might assume that the FBL approach is most compatible with this style of entrepreneurship. However, that is not necessarily the case. For example, Nina Smith founded the organization GoodWeave in 1994 with the goal of eliminating all child labor in the global carpet industry. By 2022, GoodWeave had 431 partner businesses in twenty-two countries and had restored freedom for 9,739 children.[95] Similarly, Vivek Maru and Sonkita Conteh founded Namati, which is a global organization working with communities to protect their legal rights in land, healthcare, and citizenship. Namati has helped tens of thousands of clients in numerous countries.[96] While these and other SET organizations are clearly not pursuing maximum financial profit, they are certainly examples of growth-oriented entrepreneurship both in terms of their ambitious goals and the extent of their influence.

Likewise, because of their focus on small organizations, one might assume that micropreneurs are most interested in TBL or SET approaches. It is true that many micropreneurs leave traditional jobs in FBL firms to start their own business as a way to serve social and ecological ends.[97] However, it is also true that some micropreneurs are primarily concerned with making money rather than with outcomes associated with TBL or SET management.

Multiplicity

Another characteristic that helps to differentiate among entrepreneurs is their propensity to start multiple organizations. Many entrepreneurs are monopreneurs, who start a viable organization in order to manage it for the rest of their career. Other entrepreneurs, however, find more satisfaction in starting new organizations than in managing them indefinitely. Serial entrepreneurs start many organizations. Serial entrepreneurs are typically excited by new ideas and thrive when facing the challenge of creating a new organization. Entrepreneurs of this sort often prefer the energy and uncertainty of a start-up and frequently leave managing the organization to others once it is successfully underway (see opening case, Chapter 9).

Both monopreneurs and serial entrepreneurs may adopt any of the three managerial approaches. For example, Thomas Edison founded more than 100 FBL businesses in a variety of industries related to automobiles, batteries, cement, mining, and farming.[98] Elon Musk has created TBL ventures in automotive, software, financial services, space travel, artificial intelligence, and drilling organizations (see opening case, Chapter 15).

Launch Point

The final characteristic that distinguishes entrepreneurs is whether they create a new organization or work within an existing one. When we think of entrepreneurs, we usually think of the classic entrepreneur, who starts an entirely new organization to pursue a new product or service idea. However, many new ideas, products, and services are launched from within existing organizations. Such ventures are started by intrapreneurs, persons who exhibit entrepreneurship within an existing organization. Unlike a classic entrepreneur, an intrapreneur does not create a new organization but works within one that is already operating. Many new products or services created by organizations, as well as spin-off and subsidiary firms, are the result of intrapreneurship. Some organizations even go as far as making intrapreneurship a formal part of all of their operations. For example, Google famously allows employees to devote as much as 20 percent of their work time to projects of their own choosing,[99] and 3M has a framework of internal systems, centers, and funding for developing employees’ new ideas (such as the development of Post-it Notes).[100] Much of what an intrapreneur does is similar to what any other entrepreneur does, but there are also some important differences, which are discussed at the end of Chapter 13.

All types of entrepreneurs must address all four functions of management. They must plan how to implement their idea, organize the resources to do so, lead their organization as it begins to operate, and control operations to achieve their ultimate goal. As a result, entrepreneurship offers an excellent lens for taking a closer look at every aspect of management. To help readers understand and apply the ideas in this book, each chapter ends with a discussion that connects the ideas in that chapter to the choices and challenges faced by entrepreneurs. And each chapter provides questions and guidance for developing an Entrepreneurial Start-Up Plan (ESUP), which identifies an entrepreneurial opportunity and describes a detailed management plan for acting on that opportunity (described more fully in Chapter 6). Taken as a whole, this book will help readers to better understand management, organizations, and the entrepreneurial process that is so vital to society.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- The study of management is important for five reasons:

- It develops conceptual skills that increase your likelihood of being promoted into a managerial position.

- It helps to enhance your working relationships with the managers for whom you work.

- It allows you to better understand how managers operate in different organizations and settings.

- It improves your ability to create value for society and to capture value for organizations.

- It helps you to develop a richer understanding of who you are and of your life ambitions.

- The definition of management has two parts:

(a) Management functions

- Planning means deciding on an organization’s goals and strategies and identifying the appropriate organizational resources that are required to achieve them (facilitated by entrepreneur, negotiator, and disseminator roles).

- Organizing means ensuring that tasks have been assigned and a structure of organizational relationships created that facilitates meeting organizational goals (facilitated by resource allocator and liaison roles).

- Leading means relating to others in the organizational unit so that their work efforts help to achieve organizational goals (facilitated by leader, spokesperson, and figurehead roles).

- Controlling means ensuring that an organization’s activities actually serve to accomplish its goals (facilitated by monitor and crisis handler roles).

(b) Management effectiveness

- For FBL management, effectiveness is evident when managers maximize the financial well-being of their organizations. It is based on assumptions about the invisible hand and is consistent with a consequentialist utilitarian moral point of view.

- For TBL management, effectiveness is evident when managers enhance an organization’s financial well-being while simultaneously reducing its negative socio-ecological externalities. It is based on ideas about sustainable development and is consistent with an enlightened consequentialist utilitarian moral point of view.

- For SET management, effectiveness is evident when managers enhance socio-ecological well-being while maintaining financial viability. It is based on recognizing the finite resources of the planet and is consistent with virtue ethics and other moral philosophies with a deep history in humankind.

- Studying FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to management enhances the following abilities:

- critical thinking (education vs. training; preparation for future conditions),

- ethical thinking (all management is value laden),

- cultural empathy, open-mindedness, tolerance, and creativity.

- Entrepreneurs start businesses for the following reasons:

- to gain autonomy and freedom,

- to meet challenges and opportunities,

- to achieve financial goals.

- Different types of entrepreneurs can be identified based on their scope (micropreneurs vs. growth-oriented entrepreneurs), multiplicity (monopreneurs vs. serial entrepreneurs), and launch point (classic entrepreneurs vs. intrapreneurs).

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Many people are attracted to the status, power, and financial rewards associated with being a manager. However, the lifestyle of managers can be stressful, with a high workload and an unrelenting sense of obligation and responsibility to the people being managed. For example, a 2018 Harvard Business Review study found that CEOs work an average of 9.7 hours per weekday as well as putting in work time on 79 percent of weekend days and 70 percent of vacation days.[101] What do you think are some of the pros and cons of becoming a manager? Is this a profession and a lifestyle that appeals to you? Why are you studying management?

- Which conception of management do you like better: Fayol’s theory that managers perform four functions in an orderly manner, or Mintzberg’s idea that managers play ten roles alongside other organizational actors? Can you think of additional concepts or metaphors that might be useful for understanding management?

- Some research argues that money can effectively reduce unhappiness (especially for those living in poverty) but has little ability to improve overall life satisfaction beyond that,[102] and that money and materialism are, in fact, associated with a decline in life satisfaction and personal well-being.[103] Do these findings ring true to you? Think of a person you know who is truly happy and content. What would that person say about the relationship between overall well-being and an FBL worldview? Do you think that money can buy happiness? Explain your reasoning.

- When someone is described as an “effective” or “successful” manager, do you assume that the manager is financially successful (FBL management), or do you assume they have been able maximize profits while at the same time responsibly attending to social and ecological externalities (TBL)? Or do you assume they have enhanced socio-ecological well-being (SET)? What criteria of success would you like to see used by the manager you report to? By what criteria would you like to be judged?

- Recall a current or past manager you have worked for. How would you describe that person in terms of FBL, TBL, and SET approaches? What factors did you consider?

- Why study three different approaches to management? Why not simply find the “best” or most popular approach and then learn about it?

- Do you think that TBL management is able to adequately address the socio-ecological crises that are facing humankind? If not, why do you think the popularity of TBL management has been increasing so rapidly? Do you think SET management is needed? What are factors that might impede or promote the acceptance of SET management?