Part 3: Organizing

11. Organization Design

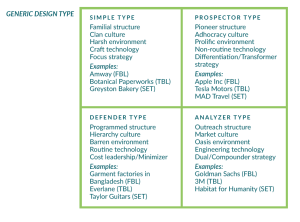

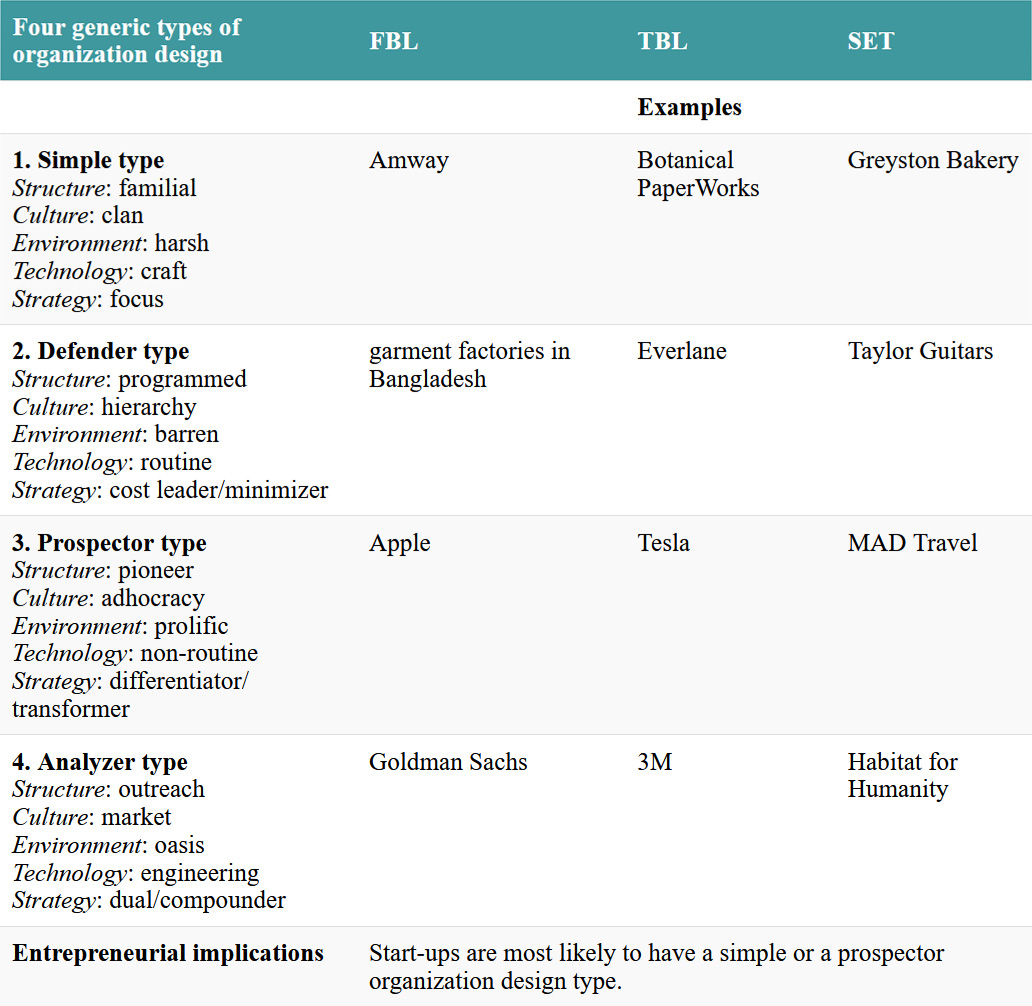

This chapter describes five elements of organization design (structure, culture, environment, technology, strategy) and how they align to produce four generic organization design types (simple, prospector, defender, analyzer). An overview of the chapter is provided in the table below and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the five basic elements that constitute organization design (structure, culture, environment, technology, and strategy).

- Identify the two underlying dimensions specific to each of the five basic design elements.

- Describe each of the four generic organization design types (simple, defender, prospector, analyzer) and how they are composed from the five basic elements.

- Describe FBL, TBL, and SET variations of each of the four generic organization design types.

- Explain how the five elements of organization design influence and constrain the choices of entrepreneurs.

11.0. Opening Case: Design for a Soup Kitchen

Nancy Elder has a challenge, and she is looking for someone with knowledge about organization design to help her. Maybe someone like you. If you met Nancy, she might tell you her story.[1]

After high-school, I decided that I would try to make this world a better place. I didn’t want to go to college just for the sake of enhancing my own career; I wanted some hands-on experience in helping people. Before long, I was doing volunteer work in a local soup kitchen.

You might be surprised to hear how many people in your community depend on food banks and soup kitchens. Food insecurity rose sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic and affects over 44 million people (one in seven) in the United States. In every single community in the country children go undernourished, and in some counties nearly half face hunger. Along with children, Black and Hispanic people are also disproportionately impacted by food security concerns.[2] The food bank in Nancy’s city is one of its fastest growing corporations, providing food for over 5 percent of the population. There are about twenty soup kitchens in the city, each feeding some 250 people a day.

You learn from Nancy that there are three types of soup kitchens. She calls the first type “carrot-and-stick” soup kitchens, where in order to get food, people need to pass through a church. The building is designed so that the only way to the soup kitchen is to go through the chapel. Clients only get their reward (carrot) after hearing a sermon (stick).

She calls the second type the “self-serving” model (no, this is not a buffet-style soup kitchen). Self-serving soup kitchens are the ones you read about in newspapers occasionally, which have a large staff and are able to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars but only direct 2 percent of the money raised to actually purchase food for hungry people. At worst, staff in such soup kitchens work there for their own self-serving reasons: feeding hungry people provides a means for the them to raise funds for their own livelihood.

The third type she describes is the “charity” model. Nancy has worked for this type of soup kitchen for five years. In this model, well-meaning people donate money and manage a soup kitchen to feed people who are less fortunate than themselves. This type relies on volunteer help and charity; anyone who wants food does not have to do anything except walk through the door and eat.

Nancy says that at first, she thought the charity model was the best. She worked hard in such soup kitchens, and after a few years became the paid manager of one. The organization she manages has two part-time staff members and an abundance of volunteers who come in to serve the 200 or so simple hot lunches that are prepared each day in a church basement. Most of the food is donated through a local food bank. The soup kitchen is governed by a board of individuals who want to help people less fortunate than themselves.

After some time, Nancy began to have doubts about the charity model. Her misgivings were triggered by some of the things she heard from the people who came there to eat. She heard them say things like “I never thought I’d drop so low as to become a charity case.” “I feel that I have no more dignity.” “It is humiliating for me to be here.” Nancy describes how this affected her:

I started to think about those comments. And I talked about the comments with my friends and associates. Were we robbing people of their dignity? Was our organization designed in such a way that we could not help but rob people of dignity? It bothered me to see how the attitude of our “regulars” seemed to change. At first, they felt badly because they did not have anything to contribute to the organization. Then, after a while, they started to think that they should not contribute anything.

I listened some more, and asked probing questions. I tried to put myself in the shoes of the people who came to eat our soup. Would I like to be treated as a charity case? What would it do to me, to my sense of self-worth, to depend on hand-outs?

I started talking about my concerns with my board members. I thought that they would provide a receptive ear. And at first, they did, but they resisted any suggestion I made about transforming the way our organization was designed, or trying to move toward a “dignity” model.

I became almost obsessed by my frustration with the charity model. Finally, the board gave me an ultimatum: “Accept the current organization design, or quit.”

Nancy asks if you would be willing to give her some advice on designing a “dignity” model organization, one where clients do not lose their sense of self-worth. She tells you that she has already made some progress in identifying sources where she thinks she could get food donations to start up such a soup kitchen, and she has some friends and acquaintances who would provide start-up money. She also says she has a site she could use. She just needs help in designing this new organization. How should it be managed? Who is welcome to join? How to start?

11.1. Introduction

Managers have long sought to discover the “one best way” to structure an organization. But happily, there is no one best way—think of how boring it would be if all organizations were structured the same way. However, research suggests that some ways of structuring an organization are better than others, and that managers should seek to design organizations in a way that optimizes the fit among a number of key elements.[3] Organization design is the process of ensuring that there is a good “fit” between an organization’s structure, culture, environment, technology, and strategy.

Although there is no one best way to organize, research suggests that it is helpful to think of four different generic organization design types, each of which may be most appropriate in a particular context. An organization design type is a coherent alignment of an organization’s structure, culture, and strategy to fit the prevailing environment and technology. In other words, there are certain organizational configurations where all the pieces fit together nicely, which is desirable. The four generic types are called simple, prospector, defender, and analyzer. These four organization design types are adaptable enough that they can be applied to Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) management, though with different meanings and nuances.

Of course, suggesting that there are only four organization design types is an oversimplification, but studying and understanding these four types has proven helpful to managers, scholars, and students. And even though the first type is called “simple,” in reality, each type is a rather complex configuration of constituent elements, or pieces, that work together to form an integrated whole. In the following sections we describe four key elements that make up organizational design: structure, culture, environment, technology. We also consider interrelationships between these elements. Then in the latter part of the chapter, we add the fifth element, strategy, and put all the pieces together to more fully present the four organization design types.

A note of caution and a suggestion before we proceed: with so many pieces and interrelationships, the information in this chapter may start to feel a little overwhelming. Although we do our best to present the material in a straightforward and systematic manner, we encourage you to spend time studying the diagrams and tables that accompany the text. Just like a picture that is worth a thousand words, these diagrams and tables can help you visualize and make sense of the content more readily. Organizational design is a bit like working on a puzzle. The art of fitting all these complex factors to work well together makes management challenging, interesting, and even fun.

11.2. Key Elements of Organization Design

11.2.1. Structure

Max Weber’s four fundamentals of organizing (presented in Chapter 10) can be combined to form two dimensions that help us understand organizational structure. The first dimension describes how the four fundamentals emphasized in the FBL approach (standardization, specialization, centralization, and departmentalization) make up a continuum ranging from mechanistic to organic. The second dimension describes how the fundamentals emphasized in the SET approach (experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation) form a continuum from internal focus to external focus. We will look at each in turn

Structure’s mechanistic–organic continuum

The four fundamentals of organizing emphasized in the FBL approach are often combined to form an overarching continuum that moves from a mechanistic structure at one end to an organic structure at the other (see Figure 11.1).[4] We will first define and illustrate the ends of this continuum, and then provide more descriptive detail in the paragraphs that follow.

A mechanistic structure is characterized by standardization, narrow specialization, centralization, and functional departmentalization. The US Postal Service is a mechanistic organization, where there are highly developed standards, job descriptions, and top-down decision-making mechanisms to guide work. In contrast, an organic structure is characterized by little standardization, broad specialization, limited centralization, and divisional departmentalization.[5] An example of an organic structure is a neighborhood pick-up sports league, where players show up if they are available and are divided into different teams each week. This mechanistic–organic continuum is conceptually powerful, and is the most widely recognized contribution in the organization design literature.[6]

Figure 11.1. The mechanistic–organic structure continuum

The logic behind the mechanistic–organic continuum is that there are interrelationships among each of Weber’s four organizing fundamentals. These fundamentals take on different forms, depending on the structural type. In other words, the fundamentals of standardization, specialization, centralization, and departmentalization look quite different in a mechanistic organization than they do in an organic organization.

In a mechanistic structure, managers rely on standardization (e.g., manuals filled with policies and rules) and tend to emphasize narrow specialization (e.g., detailed, highly-specific job descriptions). Mechanistic structures are associated with centralization (decision-making authority is concentrated at the top of the hierarchy), and tend to favor functional departmentalization (grouping employees with the same skill set). In sum, in a mechanistic structure the fundamentals fit together to form a coherent whole that operates like a well-designed machine. This structure is sometimes called a machine bureaucracy. Generally speaking, as organizations increase in size, they tend to become more mechanistic. This is because mechanistic structures appear to offer more efficient processes to coordinate the work of hundreds or even thousands of employees.

To see how the four fundamentals fit together in an organic structure, let’s discuss them in the opposite order. To begin, recall that managers with divisional departmentalization must coordinate work across a variety of functional areas (e.g., marketing, finance, and production). Because divisional managers will lack full expertise in all these areas, it is appropriate for the manager to operate with less centralization, delegating decision-making authority to expert subordinates. As members interact and work together across functions, they will tend to develop broad specializations. Finally, because of this diffuse decision-making authority and collaborative specialization, highly developed procedures and uniform work standards may not be possible or practical, resulting in less standardization. Thus, in an organic structure the fundamentals also fit together to form a coherent whole, but the structure operates less like a mechanical machine and more like a highly adaptive organism.[7]

Structure’s internal–external focus continuum

The fundamentals of organization emphasized in the SET approach (experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation) can be combined to form an overarching continuum that contrasts an internal focus structure with an external focus (see Figure 11.2).[8] An internal focus structure is characterized by an emphasis on how stakeholders within an organization’s boundaries engage in experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation, whereas an external focus structure is characterized by an emphasis on how stakeholders beyond an organization’s boundaries engage in experimentation, sensitization, dignification, and participation.

Figure 11.2. The internal–external focus structure continuum

As with the mechanistic–organic structure continuum, the logic behind the internal–external continuum is that the four fundamentals of organizing associated with the SET approach are interrelated. In an internal focus structure, when members prioritize treating each other with respect (internal dignification), they emphasize the input and concerns of members (internal participation), causing members to be attuned to one another’s work to look for new opportunities to improve their tasks (internal sensitization) and to seek new ways to improve internal operations (internal experimentation). The fundamentals thus form a self-reinforcing system, where a particular emphasis on any one factor is expected to be associated with a similar emphasis on the others. The internal focus at Greyston Bakery (Chapter 1) is evident already in its recruitment practices, where jobseekers—including people with a criminal record or who are unhoused—are hired in the order they add their names to Greyston’s Job List: “No one willing to work should be denied the dignity of a job.”[9] By meeting with apprentices every two weeks, Greyston is sensitized to their needs: “We were offering job training, but we found that many people who needed jobs didn’t have housing or childcare . . . Our approach had to include housing, childcare, job training, counseling, and the creation of jobs all at once.”[10]

In an external focus structure, when managers prioritize treating external stakeholders with respect (especially marginalized and underserved stakeholders), there is external dignification. It follows that the advice of these stakeholders will be sought (external participation), that members and stakeholders together will look for ways to improve overall multi-stakeholder well-being (external experimentation) and seek new ways to improve the effect of the organization’s activities on external stakeholders (external sensitization). MAD Travel, described in Chapter 6, provides an example of an external focus organization, where Indigenous communities and the larger landscape are treated with dignity and are important participants in the work of the organization.

Of course, as with the mechanistic–organic structure continuum, the internal–external structure continuum reflects ideal types and does not perfectly describe what goes on in any particular organization. However, it does provide a helpful conceptual framework and can help managers think about how changing one dimension (e.g., dignification) will affect another (e.g., experimentation), to ensure a good overall fit with social and environmental goals of the organization.

Combining the two continua: Four generic types of organizational structure

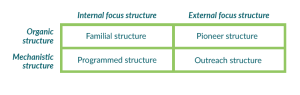

As shown in Table 11.1, the mechanistic–organic and internal–external continua can be combined to create four types of organizational structure: familial, programmed, pioneer, and outreach.

Table 11.1. Four types of organizational structure

Starting in the top left quadrant, a familial structure is organic and has an internal focus. It is often characteristic of smaller organizations, perhaps especially family firms, but it can be found in non-family firms as well. For example, Velo Renovation has few rules, is always open to new ways of doing things, and seeks to optimize the well-being of its members (opening case, Chapter 9). Shown in the bottom left quadrant, a programmed structure is mechanistic and has an internal focus This is evident in Taylor Guitars, which treats members with dignity while following rigorous standards in selecting and working with its wood. In the top right quadrant, a pioneer structure is organic and has an external focus. A firm like Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company (Chapter 7) is an example of this, perhaps especially during its early years, as it listened sensitively to the needs of local farmers and experimented with different baked goods and recipes. And finally, shown in the bottom right quadrant, an outreach structure is mechanistic and has an external focus. This is evident in organizations like Boldr (opening case, Chapter 5) that have specific rules and operating procedures to perform their tasks efficiently while simultaneously seeking to be very customer-oriented and aware of the social needs in the larger community.

11.2.2. Culture

Whereas organizational structure relates primarily to the formal aspects of management, organizational culture draws attention to the informal aspects of management. Organizational culture refers to the set of shared values and norms that influence how members perceive and interact with each other and with other stakeholders.[11] Organizational values, in turn, are the foundational beliefs that members hold about the goals of the organization and how those goals should be achieved. For example, the maximization of financial profit is an important value within FBL management, whereas values of equality and preserving nature are more prevalent in SET organizations. Choices and behaviors in any organization will tend to reflect the organization’s underlying values. Some elements of an organization’s culture and values may be highly formalized (e.g., expressed in a mission statement), but many aspects of organizational culture and values remain informal. Organizational norms are the informal rules that guide social and task behavior in a group. Although they are rarely stated explicitly, norms have powerful effects on almost all aspects of social life, including organizational life.[12] For example, in some organizations the norm is to take minutes at meetings, and in other organizations taking minutes is frowned upon (e.g., Semco).

Like structure, organizational culture varies widely and can be assessed on multiple dimensions. The best-known typology of organizational culture—called the Competing Values Framework[13]—is built on research that suggests two dimensions of organizational culture that are particularly helpful for understanding organization design. The first dimension is culture’s predictability–adaptability continuum (which aligns with structure’s mechanistic–organic continuum), and the second dimension is culture’s internal–external focus continuum (which aligns with structure’s internal–external focus continuum). Indeed, in important ways an organization’s structure and its culture can be seen as two sides of the same coin.

Culture’s predictability–adaptability continuum

In the predictability–adaptability continuum, a predictability culture refers to organizations that tend to place greater value on stability and control, and an adaptability culture describes organizations that tend to place greater value on flexibility and change. In organizations with a culture of predictability, for example, members thrive when they know exactly what times and days of the week they have regular meetings, when reports are due, who reports to whom, and so on. In contrast, in an adaptability culture, members thrive on being flexible and not knowing what sorts of things will come up at work during any particular day or week, or whom they may be assigned to work with on an ad hoc team. As noted above, the predictability–adaptability continuum of culture aligns closely with the mechanistic–organic continuum of structure. Predictable cultures tend to have a mechanistic structure, and adaptable cultures tend to have an organic structure.

Culture’s internal–external focus continuum

The second culture continuum reflects whether an organization has an internal focus or an external focus. An internal focus culture refers to organizations that place relatively more value on the needs of employees as compared to overall organizational goals. That is, the organization is a means to meet the needs of its members. By contrast, an external focus culture denotes organizations that prioritize organizational objectives over employee needs. In this type of culture, members are a means to meet the needs of the organization. Greyston Bakery’s motto—that it bakes brownies in order to hire people, rather than hiring people to bake brownies—indicates an internal focus. In contrast, impersonal organizations—where members are treated as a “number”—are more likely to have an external focus. For example, factories assembling iPhones for Apple will typically have an external focus.[14] Again, culture’s internal–external continuum aligns closely with structure’s internal–external continuum.

Combining the two continua: Four generic types of organizational culture

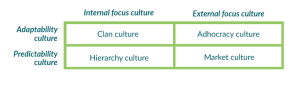

As shown in Table 11.2, culture’s adaptability–predictability and internal–external continua combine to create four types of organizational culture: clan, hierarchy, adhocracy, and market cultures.

Table 11.2. Four types of organizational culture

Starting in the top left quadrant, a clan culture values flexibility and an internal focus, emphasizing cohesiveness, morale, and the development of its members. Clan culture is characterized by teamwork, participative decision-making, and is comfortable with high levels of openness. This culture is attractive to members who value affiliation, mutual dependence, long timelines, and interpersonal relationships and processes. Compared to the other types of culture, clan culture tends to place particular emphasis on internal social well-being.[15] It is associated with developing a sense of community[16] and higher levels of job satisfaction.[17] A clan culture (and familial structure) is evident in the networks of distributors who work in an FBL firm like Amway, where salespeople look out for each other and there is a strong incentive for senior people to nurture and help junior people to increase sales of its health, beauty, and home care products.[18] It is also evident in smaller craft-based TBL firms like Botanical PaperWorks,[19] which makes handmade paper for special events like wedding invitations. And it can be seen in a SET firm like Greyston Bakery, which provides jobs, training, and work-based and personal support for chronically unemployed people.

Moving to the bottom left quadrant, we see that a hierarchy culture values predictability and an internal focus, and emphasizes bureaucratic information management systems and communication. Hierarchy culture is characterized by its emphasis on minimizing costs, smooth operations, and dependability. This culture is attractive to managers who value certainty, long timelines, security, routinization, and the systemic analysis of facts in order to find the one best way to perform tasks.[20] A hierarchy culture is evident in FBL-managed overseas garment factories in countries like Bangladesh, which place relatively high emphasis on an FBL mechanistic structure and seek to respond to pressures from external stakeholders (e.g., human rights activists, concerned consumers) to adopt more characteristics associated with an internal focus structure.[21] An example of a TBL variation is online fashion retailer Everlane, which sources all its clothing from socially responsible garment factories.[22] A SET variation was observed at Taylor Guitars, where highly routinized and systematic processes govern production, and where ownership was recently transferred from the founders to the employees of the company.

An adhocracy culture, shown in the top right quadrant, values flexibility and an external focus, and emphasizes dynamism, innovation, and growth.[23] Adhocracy culture is characterized by its emphasis on being willing to take risks and operate on the cutting edge. This culture is appealing to managers who value growth, variation, uncertainty, risk and excitement, a future orientation, and mutual influence with external stakeholders.[24] An adhocracy culture is evident in innovative FBL organizations like Apple (though not in its overseas FBL factories that manufacture its products, which would be more likely to have programmed structures[25]), TBL organizations like Tesla (though not in its established factories),[26] and SET organizations like MAD Travel.

Finally, in the bottom right quadrant, we see that market culture values predictability and an external focus, and emphasizes competitiveness, results, and constantly improving operations. Market culture is characterized by its emphasis on planning, goal-setting, and efficiency. This culture is attractive to managers who value short timelines and high certainty, and have a need for achievement and independence.[27] A market culture is evident in FBL organizations like Goldman Sachs,[28] which has very concentrated centralization[29] and an external focus on enhancing financial well-being.[30] It is also evident in a large TBL firm like 3M, whose external focus is evident in its engineers spending 15 percent of their time working on new product ideas to meet the needs of the marketplace. And a SET example is Habitat for Humanity, which has a well-developed formal structure and is always seeking to increase its support and the number of homes it can build for underhoused people.[31]

Test Your Knowledge

11.2.3. Environment

The organizational environment consists of all the actors, forces, and conditions outside the organization. This includes the various political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal factors that exist in the organization’s operating environment.[32]

Interestingly, scholars who examine how organizations fit into their broader environment often apply ideas from the natural sciences. Just as wildlife species must fit within their environment (e.g., the number of deer that a biome can support is determined by the weather, food supply, predators, etc.), so also organizations must fit within their environment (e.g., the number of gas stations a town can support is determined by the number of drivers who live in or travel through the town[33]). It is the “fittest” in this sense who survive and thrive. In the big picture, both wildlife (deer) and organizations (gas stations) must operate within the capacity of Earth’s ecosystems, which is the grand life support system for all earthly populations, human and non-human alike.

Scholars have identified many different dimensions of organizational environments for managers to consider. Among these, two dimensions are of particular interest for organizational design: the environmental stability–change continuum, and the munificence continuum. Environmental stability refers to the prevalence and speed of change among key resources and stakeholders in an organization’s external environment. A stable environment features a secure source of supply, steady demand, slow-changing technology, and government policies that are predictable and consistent. There is considerable agreement about how this dimension relates to the mechanistic–organic continuum.[34] In a stable environment, a mechanistic structure that generates uniform quality and reduces inefficiencies is recommended. However, in a dynamic and changing environment, an organic organization structure is preferred because it is more flexible and allows members to realign the organization’s products and services with those external shifts.

The second dimension, environmental munificence, refers to the availability of resources in the environment that enable organizations to grow and change.[35] In cases where the viability of an organization is threatened by a low munificence environment (i.e., low resource availability), an internal focus structure that uses limited resources very efficiently may be most appropriate. For example, if it is difficult to hire staff or find customers, managers can focus their efforts internally to retain the staff and customers they already have. Companies like Amway and door-to-door sales companies often find it difficult to attract and retain staff, and in order to fit within this environment such firms implement an internal focus to retain them.[36] In high munificence environments, managers can afford to lose current resources because there are many other, sometimes better, resources readily available. Consider the example of Tesla, which on the one hand operates very munificent environment: there is high demand for electric cars that address the concern around GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions generated by fossil-fuel powered cars. However, Tesla must continuously develop advanced technologies and infrastructure to free up or tap into that munificent environment.[37] Thus, Tesla has created proprietary charging infrastructure, longer range batteries, and sleek, iconic designs that are attractive to consumers.[38] We can observe companies like Tesla using external focus structures to develop and enhance their market’s munificence.

Combining stability and munificence: Four generic types of organizational environment

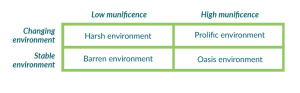

Once again, we can combine the dimensions of stability–change and low–high munificence to create a typology, in this case of generic organizational environments. As shown in Table 11.3, four types of environments result: harsh, barren, prolific, and oasis.

Table 11.3. Four types of organizational environment

A harsh environment (top left quadrant) is characterized by rapid change and low munificence. Start-up organizations in general often face a harsh environment as they seek to become known and trusted and compete with established firms. Organizations in a harsh environment must constantly change and adapt to their environment and/or find ways to stabilize their resource supply to decrease the impact of external shifts. For an example of adaptation, consider a neighborhood restaurant that, in order to accommodate demographic shifts within the community, changes from being a family-friendly pizza place to a young adult hangout, and then to a formal dinner place. An example of stabilizing the resource supply is when an organization secures long-term contracts with suppliers or customers. Greyston Bakery (SET) has a contractual commitment from Ben & Jerry’s ice cream to purchase most of the 6 tons of brownies Greyston produces each day.[39] Botanical PaperWorks (TBL) uses its reputation and ability to fulfill orders in a timely fashion to compete against its lower-priced overseas competitors, and Amway (FBL) establishes ongoing personal relationships with customers and distributors to protect itself from the stream of competitive products in its market.

A barren environment (bottom left quadrant) is characterized by stability and low munificence; managers therefore go to great lengths to retain valuable resources that are in short supply. The stakeholders who provide key resources need to be attended to closely and even coddled.[40] For example, professional sports teams use extremely generous pay and benefits packages to attract and retain their key (human) resource, which is in very short supply: top athletes. For garment factories in Bangladesh (FBL), securing long-term contracts is essential to maintain their key resource, which is orders from retailers. In a competitive marketplace for responsible fashion where customer trust is low, Everlane (TBL) seeks to enhance trust by being transparent, though it has also been accused of greenwashing.[41] Taylor Guitars (SET) purchased the company that provides it with rare ebony.

A prolific environment (top right quadrant) is characterized by rapid change and high munificence. Apple (FBL) is always looking for “the next big thing,” and its successes (e.g., the iPhone) pay for innovative products that are less successful (e.g., Apple TV).[42] Tesla (TBL) can also be seen as competing in a prolific environment, given the changes that are occurring in the automobile industry (e.g., changing consumer and regulatory demand for cleaner emissions) and growing munificence (e.g., government incentives for EVs in some jurisdictions). The environment of MAD Travel (SET) is also changing, due in part to its success in growing the local demand for ecotourism.

The oasis environment (bottom right quadrant) is characterized by stability and high munificence; it therefore attracts many competitors. Organizations in this quadrant typically focus on growth, taking advantage of both existing and new opportunities while also reducing the number of competitors. Examples include Goldman Sachs (FBL), which, notwithstanding the changes since the 2008 financial collapse, is competing in a fairly stable and munificent environment (i.e., financial institutions continue to report disproportionately high profits). Similarly, 3M (TBL) may be seen as competing in relatively stable environments (e.g., Scotch Tape, Post-It Notes, Thinsulate) as well as in new munificent environments (one-third of 3M’s sales have been generated by products that were launched within the past five years).[43] Habitat for Humanity (SET) also operates in an oasis environment because there is an unfortunately stable supply of underhoused people, and there are philanthropically minded people willing to help (though perhaps never enough).

Test Your Knowledge

11.2.4. Technology

The fourth element of organizational design, technology, refers to the combination of equipment (e.g., computers, machinery, tools) and skills (e.g., techniques, knowledge, processes) that are used to acquire, design, produce, and distribute goods and services. Once again, we present two dimensions of technology—task analyzability and task variety—and consider these in relation to organizational structure.

The first dimension, task analyzability, refers to the ability to reduce work to mechanical steps and to create objective computational procedures for problem solving. As you might guess, high task analyzability tends to be associated with a mechanistic structure.[44] This is not limited to simple tasks: even something as complicated as building a car can be subdivided into many separate steps. In contrast, work that cannot be reduced to mechanical steps, even something as simple as an artist drawing a picture with a pencil, is typically associated with a more organic structure.

Second, task variety refers to the frequency of unexpected, novel, or exceptional events that occur during work. When tasks have low levels of variety (i.e., jobs tend to be predictable), an internal focus structure may be more appropriate to help keep workers engaged and motivated. When task variety is high, and especially if the causes of variety are external, an external focus structure may be more appropriate. These differences will become more apparent as we describe the typology created when task analyzability and task variety are combined.

Combining analyzability and variety: Four generic types of organizational technology

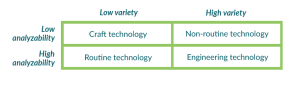

Table 11.4 shows how four types of organizational technology result when combining the dimensions of analyzability and variety: craft, routine, non-routine, and engineering.

Table 11.4. Four types of organizational technology

Craft technology (top left quadrant) is characterized by work that has low analyzability and low variety. Such work in is often based on tacit knowledge that is applied in predictable settings. This might include the performing arts, teaching, and general management. Craft technology may also be evident in some “continuous process” organizations where much of the work is done by machines but where people’s tacit knowledge is required to oversee the machines and ensure that they are operating properly (e.g., the finer nuances of brewing beer). Just like teachers and artists, such workers are troubleshooters where the nature of problems is often difficult to predict. Craft technology tends to fit with an internal focus structure and a more organic organization structure. A now-classic study by Joan Woodward found that continuous process manufacturers achieved higher financial performance if they had a more organic organization structure (due to challenges in standardizing a continuous process).[45] Examples of craft technology include the work of personal sales in Amway (FBL), handmade paper making at Botanical PaperWorks (TBL), and the art of baking specialized products for high-end restaurants at Greyston Bakery (SET).

Routine technology (bottom left quadrant) is characterized by work that has high analyzability and low variety. Work in such organizations can be broken down into separate steps and exceptions to standard ways of operating are rare, thus making it suited to a mechanistic structure. A common example is traditional assembly-line technology. Jobs like bank tellers, data entry workers, and tollbooth operators would also be highly routine. Routine technology that is coupled with an assembly-line technology has been associated with increased financial performance, as is the case in garment factories in Bangladesh (FBL). Such jobs would also benefit from an internal focus structure, especially in situations where the workers themselves do not interact with external stakeholders, as is the case for employees performing routine tasks in Everlane (TBL) and Taylor Guitars (SET).

At the other extreme, non-routine technology (top right quadrant) is characterized by work that has low analyzability and high variety. Work in such organizations cannot easily be broken down into separate steps and there are many one-of-a-kind activities. The work of professors in universities, management strategists in consulting firms, and founders in entrepreneurial start-ups may be characterized as having a non-routine technology. Joan Woodward found that when manufacturers relied on “small-batch” technologies to do custom work (e.g., unique short-run or one-of-a-kind products), an organic structure was associated with increased financial performance because it was a better fit. This quadrant also tends to be associated with an external focus structure because the adoption of non-routine technology is often driven by the specific and changing needs of external stakeholders. Examples may include product designers Apple (FBL), Tesla (TBL), and tour guides at MAD Travel (SET).

Engineering technology (bottom right quadrant) is characterized by work that has high analyzability and high variety. Many professional jobs, including those of engineers, lawyers, and tax accountants, employ engineering technology. The most appropriate structure for this technology is a mechanistic one with an external focus.[46] Representative examples include Goldman Sachs (FBL), 3M (TBL), and Habitat for Humanity (SET).

This concludes our “deep dive” into the constituent elements of organizational design. Observant readers will have noticed that we’ve covered structure, culture, environment, and technology, but seem to have missed one element: strategy (focus, cost leader/minimizer, differentiator/transformer, dual/compounder). This is because Chapter 8 was devoted to strategy. It may help to look back for a quick refresher because now it’s time to put all the pieces together. In the next section we combine the five elements of organizational design, including strategy to present the four generic organization design types.

Test Your Knowledge

11.3. Four Generic Organization Design Types

By combining the organization design elements we have presented thus far, we can identify four generic organization designs: simple, defender, prospector, and analyzer.[47] As depicted in Table 11.5, these four types tend to be aligned with specific configurations of design elements.

Table 11.5. Four generic types of organization design

Of course, although the four types as described in Table 11.5 seem complex, they are still a simplification of what managers face in their organizations. For example, in the so-called real world there is considerable variation among organizations within each generic design, and few if any organizations will fit a given configuration perfectly. Consider this analogy: even though there are a lot of components that make up a motorized vehicle (engine, tires, seat, steering, etc.), we can nevertheless combine them into generic types of motorized vehicles (cars, vans, trucks, motorcycles). And even though it is helpful to think of generic types of motorized vehicles, there is much variation within each category (e.g., a car can be further specified as a sedan, coupe, hatchback, roadster, or alternatively, as a Ford, Ferrari, Honda, Hyundai, etc.). So while generic categories help bring conceptual order to the world, we must remember that they are an abstraction of the real world and leave out many details. At the same time, we can still recognize that when shopping for a vehicle, it’s really helpful to distinguish cars from vans, trucks, and motorcycles. Similarly, distinguishing between simple, defender, prospector, and analyzer generic types helps us better understand and make sense of the organizational world.

An organization with a simple organization design tends to have a focus strategy, a familial structure and clan culture, a harsh environment, and a craft technology. Smaller companies, start-ups, and family businesses often fit the simple design profile. Imagine, a family-run restaurant popular for its special atmosphere and “grandma’s” traditional recipes (focus strategy: differentiation). The restaurant has provided stable employment for multiple generations of family members (familial structure), and that special atmosphere is closely tied to the family’s tight-knit dynamic and cohesive working relationships (clan culture). The community around the restaurant has been developing rapidly in recent years and a number of new restaurants have opened offering all manner of global cuisine (harsh environment), but people keep coming for those “down-home” dishes that only grandma can make (craft technology). Even if this restaurant is only in your imagination, you probably recognize that all the pieces fit together to form a coherent whole.[48]

An organization featuring our second generic type, a defender organization design tends to have a cost leader or minimizer strategy, a programmed structure and hierarchy culture, a barren environment, and a routine technology. Compared to the simple type, defender organizations are typically larger, older, and more established companies with a core product or service offering. This time, imagine a branch of a national auto-parts supplier that sends out weekly flyers featuring a broad selection of discounted items on sale (cost leadership strategy). Even though you don’t visit often, you recognize the staff because most employees have worked in the same role, in the same department, reporting to the same manager for many years, thanks to the job security, reasonable wages, and congenial atmosphere (programmed structure, hierarchy culture). There are a number of very similar parts suppliers in the city, and customers tend to frequent whichever is most convenient (barren environment). Nonetheless, there always seems to be enough work to go around, and employees are kept busy serving customers, stocking shelves, and processing special orders (routine technology). This story may resonate if you’re familiar with auto-parts suppliers because again, the pieces tend to fit together.

Our third generic type is the prospector. A prospector organization design tends to have a differentiator or transformer strategy, a pioneer structure and adhocracy culture, a prolific environment, and a non-routine technology. Young, dynamic, and innovative firms generally fit the prospector profile. Our hypothetical example here is a small team of engineers working to commercialize their latest university-based research project: an artificial intelligence–enhanced robot designed to assist patients with progressive dementia (differentiation strategy). Although commercialization presents formidable challenges and requires each team member to “wear many hats,” they remain passionate, believing their innovations will measurably improve the well-being of dementia patients and caregivers (pioneer structure, adhocracy culture). They also see great potential for adapting the product to the specific needs of other patient populations, made possible by their innovative integration of numerous cutting-edge technologies (prolific environment, non-routine technology). Perhaps there’s a team working on something just like this in a research lab or tech incubator near you.

We now come to the last of the four generic design types. An analyzer organization design tends to have a dual (cost leader plus differentiator) or compounder (minimizer plus transformer) strategy, an outreach structure and market culture, an oasis environment, and an engineering technology. Analyzers can be thought of as part defender and part prospector, and sometimes employ a hybrid structure to accommodate these different aspects. Public institutions (e.g., hospitals, universities), established companies with intrapreneurial divisions, and firms that develop customized, project-based products and services tend to fit the analyzer profile. For this type we will imagine a major property development firm in a large and growing metropolitan area. Typical projects include large-scale community centers, concert theaters, megachurches and sports complexes, most of which are awarded on the basis of competitive price bids and progressive design features (cost leader plus differentiation strategy). Due to the complexity of the projects, and the need for close and extended coordination with a complex customer (municipalities, faith groups, etc.), employees typically have dual reporting to both a functional team lead who oversees a given profession or trade, and a project manager responsible for overseeing all professions/trades on a given project (outreach structure, market culture). The region’s economy continues to attract business investment along with a steady stream of young, aspiring professionals, and the firm looks forward to applying its design-build expertise on standout development projects for many years to come (oasis environment, engineering technology). The analyzer is clearly quite different from the preceding types, yet once again we observe complementary between the various design elements and coherence in the overall form.

Test Your Knowledge

11.4. Entrepreneurial Implications

In this final section, we examine some of the implications of organization design for entrepreneurs, both in terms of how entrepreneurs can use the tools in this chapter to make decisions, and how research findings point to certain constraints on the options available. But first we highlight aspects of the larger cultural environment that entrepreneurs should take into consideration when choosing their strategy and design.

11.4.1. Cultural considerations

Recall that organizational culture consists of shared values and norms among members. However, culture also exists outside of organizations and can powerfully influence the success of an organization.[49] Entrepreneurs must pay attention to both societal and industry culture when they design their organization’s structure. In some countries it is normal and valued for authority to be centralized at the top of the organization’s hierarchy (e.g., India, Malaysia, Philippines), whereas other countries value authority being diffused throughout an organization (Austria, Denmark, Israel).[50]

This provides direction for how organization structures should be designed, and also explains why the same organization design can be interpreted differently by members in different countries. In Mexico, where people tend to have a high deference to authority, managers who try to empower members and promote participative decision-making may be perceived as shirking their leadership responsibilities. In contrast, in Israel, where people tend to have a low deference to authority, managers who try to use a centralized decision-making approach may face resentment from members.

Industries can also display aspects of culture that may influence the operation of an entrepreneurial organization. FBL entrepreneurs may have difficulty acquiring financial resources if investors predominantly value TBL management. The recent global trends toward sustainable ESG (economic, social, and governance) investing suggest that market-based financing will increasingly favor TBL start-ups. Likewise, if there is a dominant organization in the industry, it may have shaped practices to its benefit, and in ways that make it more difficult for new firms to enter. For example, a new app needs to work with the operating systems on the devices it is targeting, and the start-up needs to follow the rules of the relevant stores promoting the app.

11.4.2. Entrepreneurial options in organization design

As discussed in Chapter 10, classic entrepreneurs—those starting new organizations based on product or service innovation—are likely to adopt an organic structure and lean toward the SET fundamentals of organizing. This has important implications for the start-up’s organizational design. In particular, it suggests that most start-ups will adopt either a simple (organic with an internal focus) or prospector (organic with an external focus) organization design.

Organization designs to consider: Simple and prospector

Of course, any organization can have any design its founder wishes, but if the design does not fit the environment and technology, the new organization will struggle to succeed. As we have seen in this chapter, the simple and prospector designs are well-suited to particular types of environments, technologies, and strategies. A simple design is especially appropriate when the environment is changing and has low munificence. This applies to entrepreneurs who are relatively new to an industry (and thus always learning something new about it) and do not yet have stable customers. A simple design is also appropriate when the entrepreneur is not yet aware of the best technology to use and needs to tweak things until they develop sufficient expertise. Here a focus strategy works best, as the entrepreneurial organization seeks to find its place in its industry over time.

A prospector design is especially appropriate when the entrepreneur perceives the environment as changing and having high munificence. This describes entrepreneurs who are relatively new to an industry or perhaps entering a relatively new industry (and thus always learning something new about it), and where there is a strong demand for their new product or service. A prospector type is also best when the start-up is not yet aware of the best technology to deliver its product or service and there is a lot of task variety. Here a differentiation or transformer strategy works best, as the entrepreneurial organization finds its place in the industry.

Overall, entrepreneurs need to be careful to analyze their environment and technology when designing their organization and to target opportunities where their relative flexibility is an advantage. If the environment is stable, they may wish to target a sub-environment that is changing. If the technology is highly analyzable, they may wish to focus on an emerging technology that is less analyzable. For example, the founder of MAD Travel knew it could not compete with mainstream tour operators in an industry that was fairly stable and analyzable. So MAD Travel focused on socially responsible ecotours, a new, less stable but potentially munificent segment of the industry. To enter this market successfully, the founder worked with and learned from partners and clients before developing the most appropriate organization design for their start-up.

Organizations designs to avoid: Defender and analyzer

Looked at from another perspective, there are organization designs that entrepreneurs may want to avoid. Consider the case of the defender type. To fit this generic design, an entrepreneur would need to adopt a cost leader strategy, which often favors large-scale production that creates economies of scale, or some other cost-saving advantage. A start-up is unlikely to have access to such resources. In addition, the prototypical defender context is an industry with a stable, well-established market, routine technology, and low munificence. This combination of features creates significant barriers to entry.

Imagine trying to launch a new online bookstore in the age of Amazon. Buyers have been conditioned to expect cheap books, the technical aspects of online book shopping are clearly defined, and there is already a dominant organization in the industry. Why would publishers want to enter into deals with your new bookstore? How could you offer a price that was better than the competition’s, especially while you are learning the technology and routines, and running an under-capitalized new firm with limited inventory? As you can see, the prospects for a defender start-up are not promising. Of course, as examples like Boldr attest, there are exceptions to the rule, but those start-ups typically require extraordinary planning and a significantly different supply chain and value proposition (e.g., based on SET management).

The likely success of an analyzer start-up is equally low. The munificence of the environment in a stable market will have attracted other firms and there are likely to be one or more cash cows in operation. That source of reliable income would allow incumbents to defend their position and out-compete start-ups. The engineering technology is complicated, and so favors established firms with more numerous and experienced members. It is hard to imagine that a classic entrepreneur could expect to generate enough profit to attract investors and justify their new venture’s operations.

There are two exceptions where entrepreneurs might successfully enter a market with a defender or analyzer design. The first is when a group of founders with deep industry experience is aware of under-tapped niches in the environment and can attract substantial investment from the outset. The second is in the case of franchising, if franchising support is sufficiently developed and the established brand is strong enough to create a pre-existing customer base.

In sum, most entrepreneurs, regardless of their management approach, are likely to start with a simple or prospector organization design. It may be done through a focus strategy that maximizes fit in a specific niche (simple) or through a differentiation/transformer strategy that showcases the entrepreneurial innovation (prospector). Thus, though all start-ups are likely to be relatively organic, the entrepreneur needs to consider whether the structure and culture should be internally or externally focused. In part, this decision should reflect how munificent the environment is and how much task variety their work will involve.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Organization design addresses the need for a proper fit between various elements of the organization and its external environment.

- The five basic elements of organization design consist of structure, culture, environment, technology, and strategy.

- (i) Structure has two primary dimensions or continua: mechanistic–organic and internal–external focus. Combining these two dimensions creates four types of structures: familial, programmed, pioneer, outreach.

- (ii) Culture has two similar underlying dimensions or continua: adaptability–flexibility and internal–external focus. Combining these two dimensions yields four types of culture: clan, hierarchy, adhocracy, market.

- (iii) Environment has two primary dimensions: stability and munificence. Combining these dimensions results in four types of environments: harsh, barren, prolific, oasis.

- (iv) Technology also has two primary dimensions: analyzability and task variety. Combining these yields four types of technology: craft, routine, non-routine, engineering.

- (v) Strategy can be one of four generic types: focus, cost leadership/minimizer, differentiation/transformer, and dual/compounder (see Chapter 8).

- The five design elements tend to align in specific configurations that are represented in four generic organization design types: simple, defender, prospector, and analyzer. Each type represents an integrated and coherent whole.

- (i) The simple type has a focus strategy, familial structure, clan culture, harsh environment, and craft technology.

- (ii) The defender type has a cost leadership or minimizer strategy, programmed structure, hierarchy culture, barren environment, and routine technology.

- (iii) The prospector type has a differentiation or transformer strategy, pioneer structure, adhocracy culture, prolific environment, and non-routine technology.

- (iv) The analyzer type has a dual (cost leader plus differentiation) or compounder (minimizer plus transformer) strategy, outreach structure, market culture, oasis environment, and engineering technology.

- Classic entrepreneurial start-ups are most likely to have a simple or prospector organization design.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Identify the five key elements of organization design. Which elements do you think are particularly important from an FBL perspective? A TBL perspective? A SET perspective?

- Recall that in Chapter 1, we indicated that conceptual skills are key for explaining which managers get promoted. Do you think that students who master this chapter are more likely to get promoted? Explain your reasoning.

- Describe the four generic organization design types. What are their key features? What are the key differences between these types under FBL, TBL, and SET management approaches?

- Visit a small independent business in your community and chat with the manager to determine how it operates and what kind of organization design it has. Briefly describe its structure, culture, environment, technology, and strategy. Would you classify it as an FBL, TBL or SET organization? Explain your reasoning. Determine which generic organization design type it is most similar to. What advice would you give to the managers to develop a better fit among the elements of organization design? If the organization already has a good fit, do you think that the organization will have to change to a different organization design type in the next five years in order to maintain its fitness? Explain your reasoning.

- Now that you have developed an understanding the constituent elements of organizational design and the four generic design configurations, you should have a better sense of how to advise Nancy Elder, our soup-kitchen protagonist from the opening case. Given her goal to create a soup kitchen with a “dignity” focus, what should each of the design pieces look like? How might you manipulate the design levers to ensure overall coherence and a good fit between the organization and its environment? Is there a generic design that will work well? What tweaks might be required to fit the particulars of Nancy’s situation? What special considerations might be needed, given that this will be a start-up enterprise and Nancy will be acting as an entrepreneur?

- Suppose that you are making plans to start a new organization and are designing an Entrepreneurial Start-up Plan (ESUP) for it. What type of environment will your organization face? What technology will it use? Given these conditions, which generic organization design would be best? Explain your reasoning.

- In Chapter, 10 you made choices about the four fundamentals of organizing for your ESUP. Which kind of generic organization design(s) do those choices imply? Is your answer the same as the design you chose in question 5 above? If not, what does that difference mean for your plans? What will you do in response?

- Some of the details in this case have been disguised. It is based on a presentation by the protagonist, and draws heavily on Dyck, B., & Neubert, M. (2010). Management: Current practices and new directions. Cengage/Houghton Mifflin. ↵

- Feeding America. (2024). Map the meal gap 2024. Food insecurity report briefs. Retrieved from https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/map-the-meal-gap/overall-executive-summary ↵

- This idea of fit draws heavily from contingency and configuration theory approaches to organization design. See Child, J. (1972). Organizational structure, environment, and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology, 6(1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/003803857200600101; Meyer, A. D., Tsui, A. S., & Hinings, C. R. (1993). Configurational approaches to organizational analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6): 1175–1195. https://doi.org/10.2307/256809; Walker, K., Ni, N., & Dyck, B. (2015). Recipes for successful sustainability: Empirical organizational configurations for strong corporate environmental performance. Business Strategy & the Environment, 24(1): 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1805; Dyck, B. (1997). Understanding configuration and transformation through a multiple rationalities approach. Journal of Management Studies, 34(5): 793–823.Configuration ideas have also been applied to the study of leading sustainable organizations: Cantele, S., Leardini, C., & Piubello Orsini, L. (2023). Impactful B Corps: A configurational approach of organizational factors leading to high sustainability performance. Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management, 30(3): 1104–1120. http://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2407; Arraya, M. (2024). Capabilities configurational method for organisations’ sustainability: Antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Management Concepts & Philosophy, 17(2): 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMCP.2024.137638 ↵

- Note that our discussion of FBL organization structure builds on the work of Burns, T., & Stalker, G. M. (1966). The management of innovation (2nd ed.). Tavistock Publications. Discussion in this section also draws heavily from Dyck & Neubert (2010). ↵

- For more on the relationship between mechanistic–organic and functional–divisional departmentalization, see Burns, T., & Stalker, G. M. (1961). The management of innovation. London: Tavistock; Jundt, D. K., Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Humphrey, S. E., Johnson, M. D., & Meyer, C. J. (2004). The impact of hybrid team structures on performance and adaptation: Beyond mechanistic and organic prototypes [Working paper]. Michigan State University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235143992_The_Impact_of_Hybrid_Team_Structures_on_Performance_and_Adaptation_Beyond_Mechanistic_and_Organic_Prototypes ↵

- Donaldson, L. (1999). The normal science of structural contingency theory. In S. R. Clegg & C. Hardy (Eds.), Studying organizations: Theory and method (pp. 51–70). SAGE. For a related study, see González-Zapatero, C., González-Benito, J., Byung-Gak, S., & Lannelongue, G. (2024). Is supply chain risk mitigation affected by organisational design? The roles of organic structures and cultures. European Research on Management & Business Economics, 30(2): 100248. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2024.100248 ↵

- Note two caveats of this mechanistic–organic continuum. First, in actual practice there will be exceptions to the tendency for the four fundamentals to appear exactly in the way that they are shown on the continuum. New ventures, for example, may have a highly concentrated centralization (e.g., the entrepreneur makes all the decisions) and non-prescribed standardization and low specialization (e.g., the entrepreneur does everything “on-the-fly” and develops policies only on an “as needed” basis). Second, although thinking about the mechanistic–organic structure along a continuum has proven to be both elegant and useful, scholars have noted that some of its dimensions may be oversimplified. For example, rather than place concentrated and diffuse centralization on opposite ends of a single continuum, it may be more accurate to have two separate scales, where an organization could conceivably be seen to be getting simultaneously more centralized and decentralized. This could occur if decision-making authority was removed from middle management, with some of it going to lower-level managers (diffuse centralization) and some of it going to top managers (concentrated centralization). For more on this, see Cullen, J. B., & Perrewé, P. L. (1981). Decision making configurations: An alternative to the centralization/decentralization conceptualization. Journal of Management, 7(2): 89–103. http://doi.org/10.1177/014920638100700207 ↵

- This figure builds on Dyck & Neubert (2010); and on Neubert, M., & Dyck, B. (2014). Organizational behavior. John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Brady, M., & Halperin, J. J. (2017, April 25). Greyston social enterprise—Using inclusion to generate profits and social justice. B The Change. https://bthechange.com/greyston-social-enterprise-using-inclusion-to-generate-profits-and- social-justice-6847e7ae0832; cited on page 3 in Van Wert, C. (2018). Case study: Greyston Bakery. NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business, New York University. https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/Greyston_Van Wert_08.2018.pdf ↵

- Glassman, B., & Fields, R. (1996). Instructions to the cook: A Zen Master’s lessons in living a life that matters. Crown Publishers, pp. 96–97; cited on page 3 in Van Wert (2018). ↵

- Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership: A dynamic view. Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Anderson, J. E., & Dunning, D. (2014). Behavioral norms: Variants and their identification. Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 8(12): 721–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12146 ↵

- Malbašić, I., Rey, C., & Potočan, V. (2015). Balanced organizational values: From theory to practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(2): 437–446. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2238-0. For more on the Competing Values Framework, see Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework (3rd Ed.). Jossey-Bass. See also Giberson, T. R., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., Mitchelson, J. K., Randall, K. R., & Clark, M. A. (2009). Leadership and organizational culture: Linking CEO characteristics to cultural values. Journal of Business Psychology, 24(2): 123–137. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9109-1; Hartnell, C. A., Ou, A. Y., & Kinicki, A. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’s theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4): 677–694. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0021987; Quinn, R. E., & Spreitzer, G. M. (1991). The psychometrics of the competing values culture instrument and an analysis of the impact of organizational culture on the quality of life. In R. W. Woodman & W. A. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (pp. 115–158). JAI Press. ↵

- Xiang, L., & Yan, R. (2022, November 10). After workers flee China’s largest iPhone factory, activists demand accountability from Apple. LaborNotes. https://labornotes.org/blogs/2022/11/after-workers-flee-chinas-largest-iphone-factory-activists-demand-accountability-apple ↵

- Under FBL or TBL management, a clan would seek the financial benefits of, for example, reduced turnover costs among members. In contrast, a SET management clan organization would emphasis benefits of treating one another with dignity in ways that defy financial measurement. ↵

- Boyd, N. M., & Larson, S. (2023). Organizational cultures that support community: Does the Competing Values Framework help us understand experiences of community at work? Journal of Community Psychology, 51(4): 1695–1715. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22950 ↵

- Janjua, Q. R., Hanif, A., & Baig, M. (2021). The impact of organizational culture on job satisfaction in universities of Pakistan: A Competing Values Framework Perspective. Pakistan Journal of Social Research, 3(3): 340–351. http://doi.org/10.52567/pjsr.v3i3.256 ↵

- With sales of .7 billion (2023), Amway has long been ranked as no. 1 among the world’s multilevel marketing organizations (MLMs), and it has about 14,000 employees to support the roughly 1 million people selling its products. Schultz, H. (2024, March 12). Amway’s revenues continue decade-long slide, dropping to .7 billion. SupplySide Supplement Journal. https://www.supplysidesj.com/market-trends-analysis/amway-s-revenues-continue-decade-long-slide-dropping-to-7-7-billion; and Harmon, Z. (2024, September 30). Amway announces new president and CEO. Fox17online. https://www.fox17online.com/news/local-news/kent/amway-announces-new-president-ceo; Srilekha, V., & Rao, U. S. (2016). Distributor motivations in joining network marketing company, AMWAY. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 2(11): 2042–2049. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342436412_Distributor_Motivations_in_Joining_Network_Marketing_Company_AMWAY_Imperial_journal_of_interdisciplinary_research_2 ↵

- See Botanical PaperWorks company website: https://www.botanicalpaperworks.com ↵

- An FBL management hierarchy would tend to have concentrated centralization and emphasize financial efficiencies, whereas an SET management hierarchy would emphasize collaborative decision-making and socio-ecological efficiencies. ↵

- Abrams, R., & Sattar, M. (2017, January 22). Protests in Bangladesh shake a global workshop for apparel. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/22/business/bangladesh-protest-apparel-clothing.html; Burke, J. (2015, April 22). Bangladesh garment workers suffer poor conditions two years after reform vows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/22/garment-workers-in-bangladesh-still-suffering-two-years-after-factory-collapse ↵

- Mandarino, K. (2016). Niche brands: Understanding how niche fashion startups connect with Millennials. [Thesis, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania]. Scholarly Commons. http://repository.upenn.edu/joseph_wharton_scholars/9/?utm_source=repository.upenn.edu/joseph_wharton_scholars/9&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages; Cattermole, A. (2016). Transparency is the new green. AATCC [American Association of Textile Chemists & Colorists] Review, 16(1): 42–47. https://www.aatcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2016_Apex.pdf. Evans, E. A. (2016). Globalized garment systems: Theories on the Rana Plaza Disaster and possible localist responses [Master’s thesis, Western Washington University]. WWU Graduate School Collection, 485. http://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1489&context=wwuet&sei-redir=1&referer=https://scholar.google.ca/scholar?start=10&q=everlane&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5&as_ylo=2016#search="everlane". See also Everlane company website: https://www.everlane.com ↵

- For empirical support, see Zeb, A., Akbar, F., Hussain, K., Safi, A., Rabnawaz, M., & Zeb, F. (2021). The competing value framework model of organizational culture, innovation and performance. Business Process Management Journal, 27(2): 658–683. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349441072_The_competing_value_framework_model_of_organizational_culture_innovation_and_performance ↵

- An FBL management adhocracy would tend to emphasize instrumental goals, whereas a SET management adhocracy would emphasize sustainable innovations that enhance ecological and community well-being. ↵

- Smith, O. (2016, April 25). Inside secretive iPhone factory with safety nets “to stop workers killing themselves.” Express. http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/664296/secretive-iPhone-factory-safety-nets-stop-suicides-Apple-Petagron ↵

- Eisler, M. N. (2016). A Tesla in every garage? How not to spark an electric vehicle revolution. IEEE Spectrum, 53(2): 34–55. http://doi.org/10.1109/MSPEC.2016.7419798 ↵

- An FBL market culture would tend to focus on financial performance goals, whereas a SET market culture would emphasize socio-ecological goals. ↵

- Martins, J. (2024, October 15). 6 tips to build a strong organizational culture, according to Asana leaders. Asana. https://asana.com/resources/types-organizational-culture# ↵

- Oldfather, J., Gissler, S., & Ruffino, D. (2016). Bank complexity: Is size everything? FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the [US] Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2016/bank-complexity-is-size-everything-20160715.html ↵

- While Goldman Sachs may have a high reputation among hedge fund and institutional investors, it has had a very low overall reputation in the general public in terms of social responsibility, vision and leadership, workplace environment, emotional appeal, products and services, and financial performance, according to Harris Poll data. Goldman Sachs ranked as the company with the sixth worst reputation in Comen, E., & Sauter, M. B. (2016, May 12). Companies with the best (and worst) reputations. 24/7WallSt. http://247wallst.com/special-report/2016/05/12/companies-with-the-best-and-worst-reputations-4/ ↵

- See Habitat for Humanity Canada website: https://www.habitat.ca ↵

- Sansa, M., Badreddine, A., & Romdhane, T. B. (2021). Sustainable design based on LCA and operations management methods (SWOT, PESTEL, and 7 S). In Ren, J. (Ed.), Methods in sustainability science (pp. 345–364). Elsevier. ↵

- Usher, J. M., & Evans, M. G. (1996). Life and death along gasoline alley: Darwinian and Lamarckian processes in a differentiating population. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5): 1428–1466. ↵

- However, FBL, TBL, and SET approaches generally agree that there is not one best way to manage stable and unstable environments vis-à-vis the SET management internal–external focus continuum. ↵

- The word “munificent” (noun form of “munificence”) is defined as “very liberal in giving or bestowing” and comes from the Latin word for “generous.” Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Munificent. Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/munificent ↵

- To illustrate the point, here is an article sponsored by Amway about how it seeks to foster trust among its employees: A wellbeing company has been fostering trust among its sellers and customers for decades. Here’s what it looks like. (2024, June 5). Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/sc/how-one-wellness-company-turns-skeptics-into-supporters. See also Givens, K. D., & McNamee, L. G. (2016). Understanding what happens on the other side of the door: Emotional labor, coworker communication, and motivation in door-to-door sales. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 10(3): 165–179. ↵

- For example, when a broad cross-section of motorists begins to desire environmentally friendlier forms of transportation, then it is possible to provide integrated solutions like hydrogen fuel cells, improved public transportation, and bicycle paths. The expensive infrastructure that must be developed requires a broad base of interested drivers. However, when only a small portion of society is seeking multiple forms of well-being, then managers must rely on smaller specialty or niche markets characterized by an internal focus. This is illustrated by bicycle shops that recondition old bikes, and organizations like CarShare and Zipcar that enable members to share cars because they do not need them twenty-four-hours a day, seven days a week. ↵

- Once firms like Tesla increase the munificence of the environment, other manufacturers are sure to enter, which both nurtures further munificence (e.g., by enhancing infrastructure and legitimacy) and takes market share. The Grameen Bank may be seen as an example of a SET organization that has helped to develop a technology and munificent market (microfinancing) which others have been quick to enter. ↵

- See Jails to Jobs. (n.d.). Greyston Bakery. https://jailstojobs.org/resources/second-chance-employers-network/greyston-bakery/; and Ben & Jerry’s. (n.d.) Brownies from Greyston Bakery. http://www.benjerry.com/greyston ↵

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Harper and Row. ↵

- Rana, N. (2024). Green marketing strategies for sustainable fashion: Educating and engaging consumers. In E. Cepni (Ed.), Chaos, complexity, and sustainability in management (pp. 98–114). IGI Global; Sztanek, V. (2024, July 18). 2024 UPDATE: Does Everlane live up to its green halo? Ecocult. https://ecocult.com/is-everlane-ethical-sustainable-eco-friendly/ ↵

- Economy, P. (2024, April 4). Apple Robot: Is this the next big thing for the computer maker or the next big miss? Inc. https://www.inc.com/peter-economy/apple-robot-is-this-next-big-thing.html ↵

- Murphy, S. E., (2019, January 8). 3M embeds “sustainability value” mandate into new product development. Trellis (was GreenBiz). https://trellis.net/article/3m-embeds-sustainability-value-mandate-new-product-development/; Vij, A. (2016, May 19). How 3M makes money? Understanding the 3M business model. Revenues and Profits. https://revenuesandprofits.com/understanding-3m-business-model/ ↵

- FBL, TBL, and SET approaches generally agree that there is no one best way to manage task analyzability vis-à-vis the internal–external focus continuum. ↵