Part 2: Planning

8. Formulating Strategy

- Learning Goals

- 8.0. Opening Case — ECHOstore: A Resounding Social and Ecological Success

- 8.1. Introduction

- 8.2. Step 1: Establish the Organization’s Mission and Vision

- 8.3. Step 2: Analyze Internal Strengths and Weakness

- 8.4. Step 3: Analyze External Opportunities and Threats

- 8.5. Step 4: Choose and Develop the Strategy

- 8.6. Entrepreneurial Mission and Vision

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

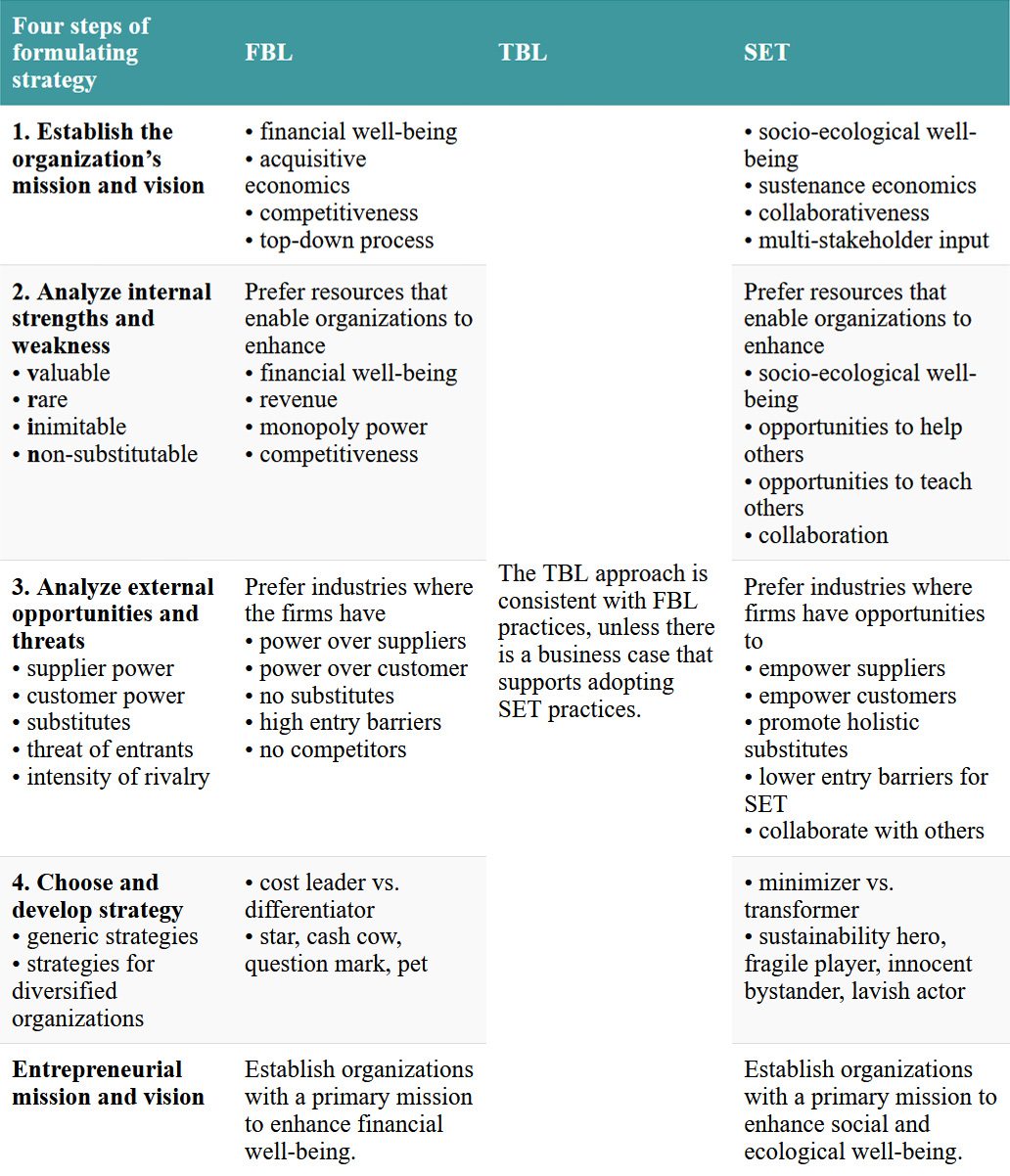

Chapter 8 provides an overview of the four steps for formulating strategy, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the four-step process for formulating strategy.

- Describe differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches with regard to establishing organizational mission and vision statements.

- Describe differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to analyzing an organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses.

- Describe differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to analyzing an organization’s external opportunities and threats.

- Describe differences between cost leader, differentiator, minimizer, and transformer generic strategies.

- Explain what a strategic business unit (SBU) is and how a diversified organization comprises a variety of SBUs.

- Describe how managers of diversified firms decide which SBUs to add and remove from their portfolio.

- Describe how entrepreneurial decisions regarding the three dimensions of well-being (financial, social, and ecological) result in eighteen potential types of organizational missions.

8.0. Opening Case — ECHOstore: A Resounding Social and Ecological Success

Imagine a retail store that sells products that are truly good for you, for the community, and for the environment. Would you shop at such a store? Would you know how to formulate a strategy to start such a business? That was the challenge facing the three co-founders of the ECHOstore Sustainable Lifestyle in 2008: Pacita “Chit” Juan, Reena Francisco, and Jeannie Javelosa. The name ECHO—an acronym for Environment, Community, Hope, Organization—encapsulates the company’s multi-stakeholder approach to business.[1]

ECHOstore opened in the heart of Metro Manila’s bustling shopping district as a pioneering green retail store quietly setting out to change how people think. Its business model centers on curating and retailing a diverse range of eco-friendly, organic, and fair trade products sourced from local farmers, artisans, and community groups across the Philippines. Their product range includes organic or natural food and body products, non-toxic home cleaning products, and staples such as organic rice and coconut sugar. The store showcases indigenous crops and products, from heirloom rice varieties to cacao products and coffee, helping consumers better understand and share the stories behind these sustainable crops.

ECHOstore has established an impressive array of internal resources, most notably its network of relationships with its suppliers and buyers. As a pioneer in the sustainable lifestyle market, the company built these relationships from the ground up. Key to doing so was the founders’ diverse backgrounds and shared passion for sustainability. Jeannie Javelosa’s development work exposed her to the challenges that rural producers face in accessing viable markets. Reena Francisco brought extensive corporate retail experience, recognizing a growing appetite for eco-ethical consumption. And Chit Juan’s entrepreneurial drive provided the catalyst to turn their vision into reality. ECHOstore’s founders personally visit farms across the country that supply their products to ensure they are sustainably sourced, non-harmful, and have minimal environmental impact. All products carried by ECHOstore are either third-party certified (e.g., fair trade) or personally vetted by the founders.

Juan, Francisco, and Javelosa took advantage of a combination of two key external opportunities related to demand and supply. First, they realized there was unmet demand for a store like the one they envisioned. Second, they recognized that there were many rural suppliers who would be interested in and benefit from accessing a larger market for their sustainable products. The challenge was to develop the networks and organization to connect these suppliers with the unmet demand.

ECHOstore saw the benefit of strengthening the capacity of suppliers in under-resourced communities, not merely to ensure consistent deliveries and high quality but also because it was the right thing to do. In this matter, ECHO has particularly focused on female suppliers, recognizing the multiple barriers to economic participation they face. A key aspect of this work has been developing partnerships and collaborating with like-minded organizations—from local governments to international development agencies—that provide complementary resources that benefit suppliers. Through its ECHOsi Foundation, the company provides its suppliers with training programs in product design, quality control, packaging, and entrepreneurial skills. By nurturing its suppliers’ capabilities, ECHOstore fosters a more resilient and sustainable supply chain. The company also leverages its industry relationships to connect community enterprises with wider markets. Partnerships with local governments, development agencies, and other retail channels help extend the reach of these small-scale producers.

ECHOstore’s strategy focuses on sustainable development and restoration. By removing barriers faced by producers, especially women, in under-resourced communities and by sourcing organic products that respect and enhance ecological well-being, their strategy seeks to nurture and sustain the following three dimensions: “The self, through a holistic lifestyle that integrates body-mind-spirit wellness; the community, through conscious consumerism, promoting fair trade and poverty alleviation programs; and the planet, through eco-friendly purchases.”[2]

ECHOstore illustrates the potential for social enterprises to generate sustainable economic, social, and environmental value. The company has achieved profitability and growth, with a loyal customer base supporting its premium, purpose-driven brand. But ECHOstore’s impact extends far beyond its balance sheet. The company has generated opportunities for hundreds of small-scale producers, many of them women and suppliers from Indigenous communities. It has helped preserve traditional crafts and sustainable agricultural practices, protecting cultural heritage and biodiversity. And it has brought the message of conscious consumption to a mainstream audience, seeding a shift towards more mindful lifestyle choices.[3]

ECHOstore: The Business of Sustainable Living (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=isyFVrfDZYs).

8.1. Introduction

Following the previous chapter, which looked at the decision-making process, this is the first of two chapters that will examine some of the most important decisions made in an organization: those involved with formulating (Chapter 8) and implementing (Chapter 9) its strategy. Strategy refers to the combination of goals, plans, and actions that are designed to accomplish an organization’s mission. Strategic management refers to the analysis and decisions that are necessary to formulate and implement strategy. Formulating strategy can be described as unfolding in a four-step process, as depicted in Figure 8.1, which will guide the organization of this chapter. While this is a useful way to think about formulating strategy, the four steps are not as neatly laid out or linear in real life, and in fact, as Chapter 9 will describe, some of the most important strategy formulation happens concurrently with strategy implementation. As usual, we will highlight the differences between Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) approaches to formulating strategy.

Figure 8.1. Four steps of strategy formulation

8.2. Step 1: Establish the Organization’s Mission and Vision

The first step in formulating strategy is to establish the organization’s reason for being (its mission or purpose plan) and define what the organization aspires to become (its vision or long-term goal). A mission statement identifies the fundamental purpose of an organization, and often describes what an organization does, whom it serves, and how it differs from similar organizations. A mission statement can help to provide social legitimacy and a sense of identity for the members of an organization. Approximately 90 percent of companies have a written mission statement.[4] Here is a sample of mission statements from a variety of organizations:

Tesla: “Accelerating the world’s transition to sustainable energy.”[5]

Walmart: “To save people money so they can live better.”[6]

Google: “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”[7]

Patagonia: “We’re in business to save our home planet.”[8]

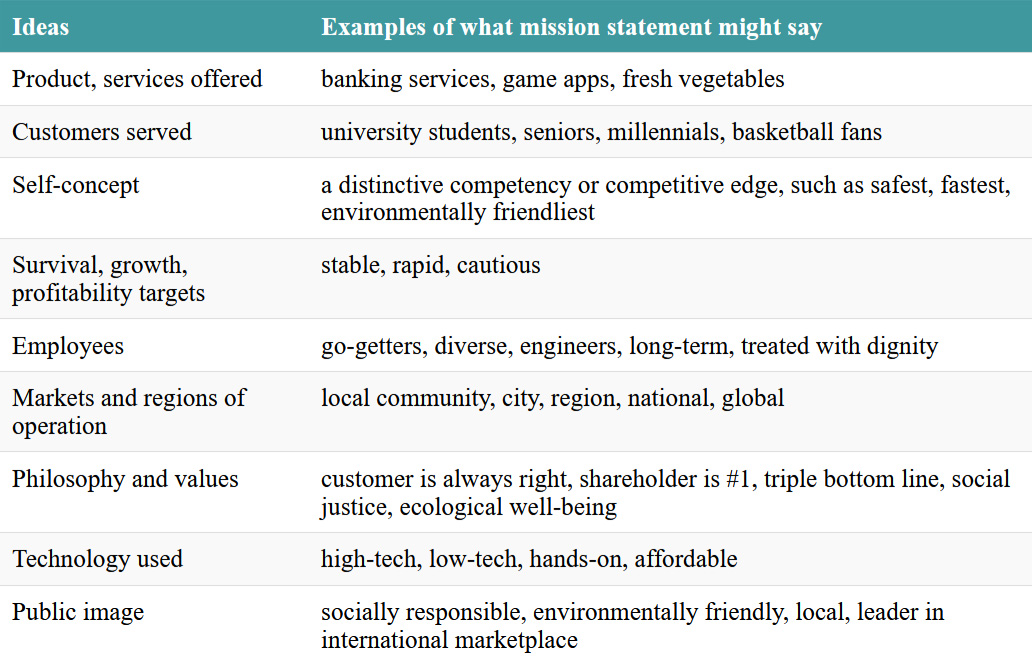

Table 8.1 lists nine ideas commonly mentioned in mission statements, with examples of what a mission statement might say about each.[9] Very few mission statements refer to all nine items. Instead, the content of an organization’s mission statement is greatly influenced by the industry it’s in. For example, one study found that more than 60 percent of banks mention “employees” in their mission statement (e.g., “we value our employees”), but less than 25 percent of computer hardware firms do so. Similarly, about 50 percent of banks’ mission statements mention the philosophy of the firm (e.g., “we believe in quality”), but philosophy is included in less than 25 percent of computer software or hardware organizations.[10]

Table 8.1. Nine common ideas in mission statements

The organization’s mission statement is often accompanied by a more aspirational and change-oriented vision statement, which describes what an organization is striving to become and thus provides guidance to organizational members. Typically, a vision statement describes goals that an organization hopes to achieve five or more years into the future.[11] For example, the mission of a university is to teach students, engage in research, and provide service to the community. The vision of a university may be to become a world leader in medical research, to maximize diversity in the classroom, or to foster a sense of global citizenship. A tourist destination may have a mission to provide local employment and to be friendly to tourists, with a vision of becoming the honeymoon capital of the world. Here are some vision statements from leading global companies:

Tesla: “To create the most compelling car company of the 21st century by driving the world’s transition to electric vehicles.”[12]

Walmart: “Be THE destination for customers to save money, no matter how they want to shop.”[13]

Google: “To remain a place of incredible creativity and innovation that uses our technical expertise to tackle big problems and invest in moonshots like artificial intelligence research and quantum computing.”[14]

Patagonia: “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, and use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”[15]

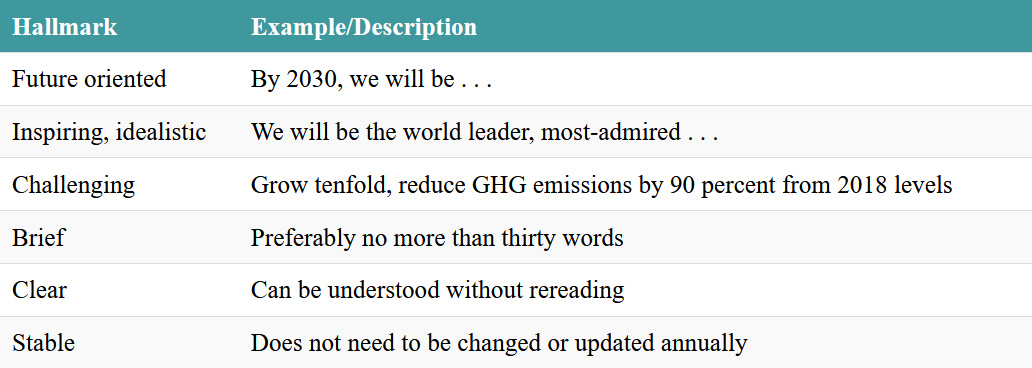

Table 8.2 provides an overview of six recommended features to include when developing a vision statement.[16] As with its mission statement, an organization’s context also influences its vision statement. For example, the performance of government service agencies vision statements may recognize the need for strong interpersonal relationships among their members (e.g., “we will provide best-in-field working conditions and service”), whereas the growth of entrepreneurial businesses may favor vision statements that express a desire for growth (e.g., “we will be #1 in our industry”).[17]

Table 8.2. Six recommended hallmarks of vision statements

Although we have described the conceptual difference between mission and vision statements, these differences are often not so clear in practice. An organization’s vision statement may include elements of its mission, such as its guiding philosophy, purpose, and core beliefs.[18] In many cases there is considerable overlap between vision and mission statements, and sometimes the two can even be interchanged with each other. The important thing is that managers develop an understanding of their organization’s overarching purpose (mission) and its long-term aspirations (vision).

8.2.1. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Mission and Vision

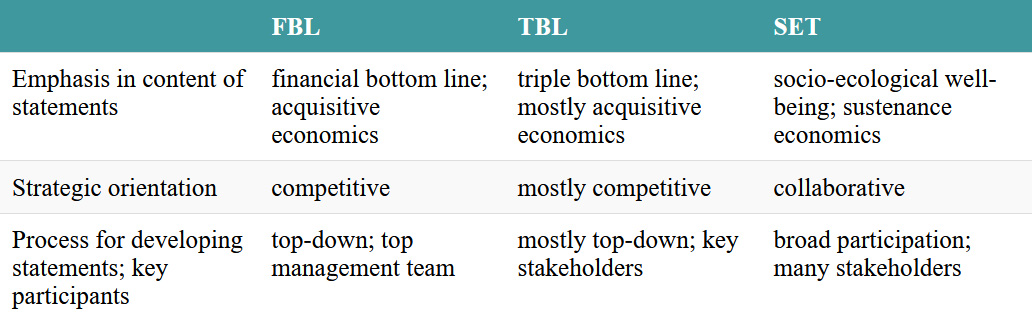

When it comes to establishing mission and vision statements, the three approaches to management will have differences in (1) the content of the statements, (2) the strategic orientation underpinning the statements, and (3) the process and people involved in developing the statements. These differences, which are evident in each stage of the strategy formulation process, are summarized in Table 8.3 and described below.

Table 8.3. Three management approaches to mission and vision statements

Content

In the FBL approach, mission and vision statements are grounded in an emphasis on acquisitive economics and factors that contribute to an organization’s financial performance. The TBL approach adds a consideration of social and ecological well-being initiatives that enhance the organization’s financial well-being; acquisitive economics is also emphasized but with some sustenance economics if it serves the organization’s financial interests. The SET approach focuses on ecological and/or social factors based on sustenance economic assumptions, as illustrated by Mother Earth Recycling, whose mission is “to provide meaningful training and employment opportunities to the urban Indigenous community through environmentally sustainable initiatives as well do our part in the Indigenous tradition of being “stewards of the land” through recycling.[19]

Strategic Orientation

Each of the three management approaches places a different emphasis on competitveness in its mission statement. An FBL approach generally stresses maximizing competitive advantage, which assumes that success depends on out-performing other organizations that offer similar goods and services. From an FBL perspective, competitiveness is good for society because it motivates people and organizations to do their best. It encourages organizations to continuously improve, promotes efficiency, and reduces opportunities to take advantage of consumers. Indeed, the merit of business competition has become so widely accepted that it seems natural and obvious.

Like FBL management, the TBL approach also emphasizes a competitive strategic orientation but at the same time recognizes that in some instances a collaborative strategic orientation may better serve an organization’s financial interests. In addition to sharing FBL management’s concern for shareholder well-being, the TBL approach is interested in mutually beneficial cooperation and the well-being of multiple stakeholders so long as they contribute to greater profit.[20]

SET management embraces a collaborative strategic orientation, recognizing that a singular emphasis on competitiveness may be dysfunctional, as is evident when people cheat in order to win. A “win at any cost” mentality can bring out the worst in people,[21] such as when athletes take illegal performance-enhancing drugs, when politicians launch personal attacks on other candidates during election campaigns, or when managers engage in illegal or unethical behavior. In contrast, a generic SET mission statement might say: “Working together with stakeholders, we will create socio-ecological and financial well-being,” which would characterize companies like Boldr (Chapter 5) and MAD Travel (Chapter 6). The SET approach challenges the assumption that the desire to compete will bring out the best in humankind and instead assumes that the desire to collaborate, to share, to eradicate poverty, to truly live sustainably on the planet, or to ensure that everyone is treated with dignity is much more likely to genuinely bring out the best in us. For example, the mission statement for Velo Renovation (see Chapter 9) could be “(1) Friends are more important than money; (2) Changing the way that people think about building.”[22]

Developing the Vision and Mission Statements

When it comes to developing mission and vision statements, FBL management emphasizes the input of the organization’s top management team, while TBL management includes other stakeholders inside and outside of the organization who can benefit the triple bottom line. The SET approach typically involves even more stakeholders, including those who are more distant from the financial success of the organization.[23] For example, a SET approach is the most likely to consider the ecological environment as a stakeholder,[24] as evident in MAD Travel’s commitment to environmental restoration.

The advantage of the FBL approach to formulating vision and mission statements is that it takes the least amount of time and is completed by the people who are likely to have the best overall understanding of an organization’s internal and external factors related to financial well-being. TBL management involves more stakeholders and thus creating these statements requires more time, but the resulting deeper understanding and participation of key stakeholders facilitates broader support and commitment. The SET approach invites the most stakeholders to participate in the process of setting mission and vision statements, which takes even more time. However, when an organization’s mission and vision consider the needs of the socio-economic and ecological environments, organizational members may find their work to be more meaningful and motivating.[25]

Test Your Knowledge

8.3. Step 2: Analyze Internal Strengths and Weakness

Managers must be aware of the available resources in their organization in order to understand its strengths and weaknesses. Strengths refer to valuable or unique resources that an organization has or any activities that it does particularly well. A strength is a positive internal characteristic of the organization that can help managers achieve their strategic objectives. Weaknesses refer to a lack of specific resources or abilities that an organization needs in order for it to do well. A weakness is a negative internal characteristic of the organization that hinders its ability to achieve its strategic objectives.

8.3.1. Three Types of Internal Resources

The best-known theory in strategy that looks at an organization’s internal resources is called the resource-based view (RBV).[26] Resources are assets, capabilities, processes, attributes, and information that are controlled by an organization and that enable it to formulate and implement a strategy.[27] It is helpful for managers to look at three different types of internal resources: physical, human, and intangible.[28] Physical resources refers to material assets an organization owns or has access to, such as its factories and equipment, its financial assets (e.g., cash), its real estate, and its inventory. Some physical resources represent tremendous strengths that other organizations may not have, such as large financial resources. Other physical resources are strategically less important, including readily available assets that are necessary simply to participate in an industry, such as buildings, office furniture, organizational websites, or vehicles.

Human resources refers to specific competencies held by an organization’s members. These include things like formal training (e.g., some members have valuable education or highly valued professional designations) and informal experience (e.g., tacit knowledge, networks, and “street smarts” that come from many years of experience). Organizations have human resource strengths if they have particularly gifted or experienced members, and weaknesses if their members lack the required experience or training. Examples of strengths include a sports team that has an outstanding athlete, a law firm with a retired judge, and a university that has a Nobel Prize winner. Weaknesses would be a sports team that lacks adequately skilled players in some positions, a law firm whose members lack expertise in important legal areas, and a university with poor teachers.

Intangible resources refers to an organization’s structures and systems. Included in this category are the organization’s formal and informal planning processes and control systems, the nature of informal relationships among group members, the level of trust and teamwork, and other aspects of the organizational culture. For example, a key intangible resource that has helped Walmart is its logistics system that allows it to distribute goods to its stores much more efficiently than its rivals. Similarly, ECHOstore’s intangible resources include its supplier development system through the ECHOsi Foundation, and its deep relationships with local governments, development agencies, and other stakeholders.

8.3.2. Four Characteristics of Strategic Resources

Managers assess physical, human, and intangible resources to identify the organization’s strengths and weaknesses. They then use this information to develop strategies to take advantage of strengths and minimize the impact of weaknesses as they seize opportunities and neutralize threats in the external environment.

Not all strengths and weaknesses are equally important. A flower shop may own a powerful computer, but this is of little importance if managers do not take advantage of its power to, say, develop an information system about its customer base. Organizations require core competencies to survive, and distinctive competencies to thrive. Core competency refers to a resource or ability that is essential for the achievement of organizational goals, such as when the flower shop has staff (human resources) who are knowledgeable about floral arranging. A distinctive competency is a competency that an organization has that is superior to that to its competitors. For example, the flower shop may have a prize-winning member who arranges flowers, or perhaps the flower shop’s location is close to a hospital, wedding chapel, or funeral home. These represent distinct advantages compared to other flower shops that have less accomplished staff or less favorable locations.

According to the RBV, the key to developing effective and sustainable strategies is to identify resources that, on their own or bundled together in a group, display four characteristics: they must be valuable, relatively rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN).[29]

Valuable resources are those that managers can use to neutralize threats or to exploit opportunities to meet their organization’s mission in light of conditions in the external environment. From an RBV perspective, an organization’s resources are not inherently valuable; rather, they are valuable only to the degree to which they enable an organization to improve its competitive position.[30] Whereas FBL and TBL approaches generally equate the value of a resource to its eventual contribution to the financial bottom-line of the organization, SET management is more likely to find resources valuable if they satisfy genuine human needs beyond maximizing finances.

Rare resources are those that few other organizations have. Common examples of rare and valuable human resources might include celebrity endorsement contracts and CEOs with an excellent track record. Whereas rare resources are valuable to FBL and TBL managers because they can help to generate higher revenues, SET managers see rarity as increasing the need to act responsibly. For example, the Earth may be the rarest thing in the universe.[31] We know of only one planet that can sustain human life, therefore we must manage this rare resource responsibly. SET managers recognize that rare resources that are valuable to humankind should not be seen merely as an opportunity to maximize financial gain.

Inimitable resources cannot be copied or developed by other organizations, or it is costly or difficult to do so. FBL managers value resources that are inimitable because this enhances their opportunity to enjoy a kind of monopoly in the marketplace. This includes patents that have generated fortunes, as illustrated by Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone and more recently Apple’s iPhone.[32] It can also include things like an organization’s unique customer-friendly culture, or its ability to learn and adapt.[33] Not all inimitable resources are valuable; for example, there are patented products for which there is no market. TBL management welcomes inimitable resources that enhance socio-ecological well-being while simultaneously optimizing financial well-being. For example, the Lincoln Electric Company has a difficult-to-copy culture with a profit-sharing program that enables both employees and owners to achieve higher-than-average financial outcomes (see Chapter 10).[34] Finally, unlike FBL and TBL managers who guard their inimitable resources, SET managers will often voluntarily share resources that they could have kept inimitable. For example, ECHOstore freely shares information about its suppliers with other firms that might want to source from them. And pioneers in the microfinancing movement, like Muhammad Yunus and Grameen Bank (see Chapter 13), have been eager to share best practices with other banks and non-profit organizations who wish to provide credit to micropreneurs.[35]

Non-substitutable resources cannot be easily substituted with other resources. Substitutes are different resources (or bundles of resources) that can be used to achieve an equivalent strategic outcome, even though the substitutes may not be rare or inimitable. This can include a firm’s organizational policies and procedures that enable it to exploit its valuable, rare, and inimitable resources.[36] For example, one organization may have a very clear vision of the future thanks to a particularly gifted CEO, while another firm has an equally clear vision thanks to a well-designed and well-functioning formal planning system. In this example, which can apply to all three approaches to management, the planning system substitutes for a gifted CEO, and vice versa.[37]

Test Your Knowledge

8.4. Step 3: Analyze External Opportunities and Threats

As is evident in a number of chapters in this book, an important part of a manager’s job is to monitor and respond to the organization’s technological, political, social, and ecological environments. Managers must pay particular attention to the environment and stakeholders in their organization’s industry. As used here, the term industry refers to all organizations that are active in the same sector of social, political, and/or economic activity.[38] For example, the automobile industry is different from the education industry, which is different from the healthcare industry.

When formulating strategy, managers look for opportunities and threats in their industry. Opportunities are conditions in the external environment that have the potential to help managers meet or exceed organizational goals. Sometimes recognition of opportunities will prompt managers to revise goals, such as when Rafael Dionisio revised the goals of MAD Travel based on insights from an Indigenous elder. Threats are conditions in the external environment that have the potential to prevent managers from meeting organizational goals. Threats could include changed government regulations, new competitors, and pandemics like COVID-19. Although we have separated steps 2 and 3 in formulating a strategy, they are often combined to influence one another in a larger process called a SWOT analysis, where managers simultaneously analyze strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

The Five Forces Model is the best-known framework to help managers think about the external aspects of a SWOT analysis: key opportunities and threats.[39] This model was initially developed by Michael Porter—perhaps the world’s most-cited strategy scholar—at a time when FBL management was the dominant approach, but the model is robust enough to also be useful for TBL and SET management approaches. Although the Five Forces Model was developed to compare the relative attractiveness of different industries, it has also been used to help managers make strategic decisions within the industry where their organization operates. We will consider each of the five forces in the model: supplier power, customer power, the power of substitutes, threat of new entrants, and intensity of rivalry.

8.4.1. Supplier Power

Supplier power describes how much influence suppliers have over an organization. Supplier power generally decreases as the number of suppliers increases. For example, if there are many different suppliers of commodities like paper and pens, then managers are more likely to be able to negotiate low prices when purchasing basic office supplies.[40]

FBL managers prefer industries where an organization’s suppliers lack power over it. FBL managers focus on optimizing their firm’s competitive position and relative power, so they prefer situations where there are many suppliers, thereby minimizing the need to become dependent upon one (or a few) suppliers. This enables managers to choose from many potential competing suppliers and easily switch to the one offering the lowest price.[41]

TBL management resembles the FBL approach, except that TBL management may be less focused on optimizing relative power over suppliers and more likely to look for opportunities to reduce socio-ecological externalities by entering long-term win-win relationships with suppliers if this enhances financial well-being. For example, Costco has actively worked to increase the number of suppliers of organically grown produce and is happy to enter mutually beneficial long-term relationships with specific suppliers.[42]

The SET approach is even more committed to collaborative relationships with suppliers to develop mutually beneficial opportunities, especially to enhance positive externalities. From a SET perspective, suppliers are seen as partners, and empowering and strengthening partners is desired, as is evident in ECHOstore’s programs to train and support suppliers.

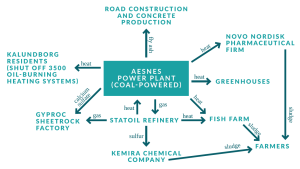

A community of TBL and SET organizations in Kalundborg, Denmark, where firms work collaboratively to reduce negative ecological externalities, provides a helpful example of several of the Five Forces in practice. Although these firms operate in a variety of industries, they belong to the same place-based ecological community. Managers in this community take the so-called waste that is produced by one organization and change it into inputs that are valued by a different organization (see Figure 8.2). It began when the coal-fired Aesnes power plant stopped pouring its “waste steam” heat as condensed water into a nearby fjord. Instead, managers at Aesnes began to sell that heat directly to two other organizations in the community at the time: the Statoil refinery and the Novo Nordisk pharmaceutical firm.[43] Not long after this, the Statoil refinery installed a process that removed sulfur from its “wasted” gas. Statoil then sold the extracted sulfur to the Kemira chemical company and sold the cleaner-burning gas to the Gyproc sheetrock factory and to Aesnes (which thereby saved about 30,000 tonnes of coal). When Aesnes began to remove the sulfur from its smokestacks it produced calcium sulfate, which it sold to Gyproc to use in place of mined gypsum. “Waste” fly ash from Aesnes coal generation is used for road construction and concrete production. In time, Aesnes began to provide surplus heat to residents of the town (who were then able to shut off 3,500 oil-burning heating systems), to greenhouses, and to a fish farm. Soon “waste” heat from Statoil also went to the fish farm, helping to produce about 200 tonnes of turbot and trout sold in the French market. Sludge from the fish farm is used as fertilizer by farmers, who also receive sludge from the Kemira chemical company. All these relationships happened spontaneously without direct government regulation, and they were often motivated primarily by acquisitive economics and have yielded financial benefits (FBL and TBL approaches). Over time some initiatives have been motivated largely by ecological reasons, without optimizing financial payoffs (SET management).[44]

Figure 8.2. Transfer of previous “waste” within a community of organizations

Whereas FBL management is concerned with minimizing dependence on suppliers, the example above shows that TBL and SET firms may welcome some dependence on new (trustworthy) suppliers who reduce negative externalities by transforming their underutilized resource outputs (“waste”) into materials for inputs.

8.4.2. Customer Power

Customer power describes how much influence customers have on an organization. Customer power generally decreases as the number of customers increases. For example, the consumer goods manufacturer Procter & Gamble had a lot of power to set prices for its products when its customers were many locally run department stores. However, with the growth of large retailers like Walmart and Target, Procter & Gamble’s main customers were fewer and larger, leaving it much less power to set the prices for the products it sold to retailers.

Firms with an FBL perspective prefer industries where customers have little power to negotiate for lower prices, where customer demand exceeds the amount of product they can supply, and where sales are not dependent on a handful of large customers. TBL managers also do not to want to become dependent on customers, though they are more willing to do so than FBL managers if it reduces overall negative externalities in a way that enhances their organization’s financial interests. In the example from Kalundborg, Statoil is happy to depend on Kemira to purchase its excess sulfur, especially if that increases Statoil’s profits.

SET managers are even more willing than TBL managers to become dependent on specific customers in order to nurture collaboration and convert waste into something useful. In the example above, Novo Nordisk’s primary motive to transform its waste sludge was not to increase its power over the customers (farmers) who purchased the sludge but rather to help farmers meet their needs for fertilizer and simultaneously enhance positive ecological externalities. Instead of the sludge being wasted, it is transformed into nutrients to grow food.[45]

8.4.3. Power of Substitutes

In the Five Forces Model, the term substitutes refers to products or services that are similar or that meet the same needs of a customer but come from a different industry. It is important to distinguish between this use of “substitutes” and its meaning in a SWOT analysis. In a SWOT analysis, substitutability refers to how one organization’s resources can be substituted by different resources in a second organization (e.g., one firm’s gifted CEO can be substituted by another firm’s formal strategic planning process). In contrast, in the Five Forces Model, substitutes refer to how the goods and services of one industry can be substituted by the goods and services of another. For example, when managers in the airline industry try to attract customers who are traveling from one city to another, those customers can also find substitute travel options on trains or buses, or use services like Zoom that eliminate their need to travel altogether. Any product or service from another industry that fulfills the customer’s’ need is a substitute.

FBL and TBL approaches to management usually seek to suppress or minimize possible substitutes. These suppression attempts may or may not be successful. For example, whereas major automobile manufacturers have made plans to phase out gasoline-powered cars and switch to electric,[46] several decades ago leading businesses in the automobile industry tried to suppress the development of electric cars, arguing that they were unsafe. Moreover, at that time it was much more profitable to sell trucks than it would have been to develop electric cars, and it was not in the industry’s short- to medium-term financial interest to question the environmental sustainability of its mainstay products (i.e., vehicles powered by fossil fuels).[47] TBL management is also likely to restrict substitutes, except when substitutes offer an opportunity to optimize financial performance via socio-ecological means.

SET management is the most likely to embrace substitutes that create net positive externalities. For example, the retailer Patagonia is famous for asking customers to think twice before purchasing a new product and encouraging them to get items repaired instead (see Chapter 3).[48] And Tall Grass Prairie Bakery (Chapter 7) fosters substitutes by sharing its sourdough starter so customers can bake bread at home, and by sharing its supplier list with other bakeries in its neighborhood.

8.4.4. Threat of New Entrants

Threat of new entrants refers to the extent to which conditions make it easy for other organizations to enter or compete in a particular industry. The higher the barriers to entry—that is, factors that make it difficult for an organization to enter an industry—the lower the threat of new entrants. Government regulations can serve as barriers to entry. For example, federal licenses are required to start a new television station. Another barrier is the start-up costs to enter a new industry. The cost to open an income tax service is much lower than the cost to build an oil refinery, and therefore we would expect more new competitors in the income tax service industry than in oil refining. Economies of scale (Chapter 6) are a barrier that can prevent small firms from entering an industry with established large firms, such as the automobile industry.

FBL management prefers operating in industries with high barriers to entry, which make it difficult for potential competitors to join, thereby enhancing opportunities to maximize financial value capture. The FBL approach encourages firms to gain economies of scale, differentiate their products, and lobby the government to regulate entry. For example, Canadian telecoms have benefited from Canada’s having the highest foreign entry restrictions among high-income countries.[49]

Like FBL management, TBL management is also interested in reducing the threat of entry, unless the new entrants enable a firm to increase its profits while addressing socio-ecological issues. For example, firms in the Alberta oil sands supported and welcomed new entrants with new technologies that would help them reduce the negative ecological externalities that exist in the process of turning bitumen into oil.[50]

The SET approach is the most likely to welcome new entrants that can improve overall socio-ecological well-being. For example, as the first green retail store of its kind in the Philippines, ECHOstore could have tried to protect its first-mover advantage. Instead, the company actively works to build the entire ecosystem of sustainable business. Through its foundation and partnerships with government agencies like the Philippine Commission on Women, ECHOstore helps develop new entrepreneurs and businesses in the sustainable products space. The company’s licensing model allows other retailers to adopt its sustainable business practices, viewing new entrants as partners and collaborators in expanding the positive impact of sustainable commerce rather than as threats to its market position.

8.4.5. Intensity of Rivalry

Intensity of rivalry refers to the extent or strength of competition among the organizations in an industry. The intensity of rivalry increases when:

- an organization has many competitors seeking similar customers;

- the industry growth rate slows down or declines, so that there are fewer customers for each competitor;

- the industry has intermittent overcapacity (such as post-Christmas sales of gift wrapping paper, or sale of farm produce during bumper harvests);

- brand identity and switching costs are low (customers can shop based only on price because having a long-term relationship with a buyer is not relevant);

- an organization’s fixed costs are high and cannot be easily converted to a new industry or product (e.g., rivalry in the airline industry is intense because it is difficult to convert airplanes and workers to purposes other than flying passengers); or

- there is little ability to differentiate the product or service being offered (e.g., rivalry in the airline industry is intense because the service is very similar across competing airlines).

FBL management prefers low levels of rivalry intensity and seeks conditions where their firm essentially has a monopoly (e.g., few competitors, few substitutes, high switching costs).[51] TBL management takes the same view as FBL management, except that rivals might cooperate to enhance profits and reduce negative socio-ecological externalities. Finally, rather than seek to limit rivalry intensity per se, SET management is concerned with increasing mutually beneficial collaboration across organizations, which involves reconsidering the six factors that contribute to the intensity of rivalry. In particular, SET management welcomes

- more collaborators seeking to optimize the creation of net positive externalities;

- sustainable industries, where there is greater emphasis on creating and sustaining positive externalities than on pursuing financial growth for its own sake (e.g., SET management welcomes a decline in industries with net negative externalities, such as the conventional beef industry[52]);

- more balanced supply and demand so that everyone has enough with minimal excess or waste;

- all organizations collaborating to optimize sustainability;

- reduced fixed costs so that resources can be used as flexibly as possible to deliver a variety of goods and services in a socio-ecologically sustainable way; and

- increased ability to integrate products and services, providing optimal choices to consumers.

Collaboration is evident in the cooperation of Statoil and Aesnes to provide their “waste” heat for a fish farm, which in turn willingly provides fertilizer for farmers. It was also illustrated when three rivals in the green office buildings market—Delos, Overbury, and Morgan Lovell—formed a strategic alliance, pooling their organizational resources and know-how to share the risks and rewards for developing their market.[53] Strategic alliances will differ within FBL, TBL, and SET approaches, depending on the rewards they are designed to create.

Test Your Knowledge

8.5. Step 4: Choose and Develop the Strategy

Managers formulate strategies at two levels: (1) for organizations operating in a specific industry (generic strategies), and (2) for organizations operating in a variety of industries. We will look at each in turn.

8.5.1. Generic Strategies

When most people think about organizational strategy, they usually think about a business-level strategy, which describes the combination of goals, plans, and actions that an organization in a specific industry uses to accomplish its mission. For example, a trucking company like Reimer Express uses a business-level strategy to compete in the transportation industry. Business-level strategies are also used by managers of non-business organizations, such as a thrift store operated by the Salvation Army. While each organization will have its own distinct strategy, there are several “generic” strategies that managers may adopt and adapt for use in their organization.

The FBL Approach to Generic Strategies

Michael Porter named the two best-known generic business-level strategies: cost leadership and differentiation.[54] A cost leadership strategy is evident when an organization has lower financial costs than rivals do for similar products, so that it can capture more profit and/or a higher market share via lower prices. When cost leaders offer a portion of their financial cost savings to buyers, this can increase the cost leader’s market share and allow it to achieve further cost savings as a result of greater economies of scale. Paying attention to production and distribution efficiencies is crucial if a cost leadership strategy is adopted. Walmart became the leading retailer on the planet, thanks to using a cost leadership strategy. Internally, Walmart has a world-class inventory management system to lower financial costs. Externally, Walmart’s volume purchases give it such great buyer power that it can purchase products from suppliers at lower prices than its competitors can. As a result, Walmart can have higher profit margins on its products while at the same time pricing its products lower than its competitors do, resulting in increasing market share and high revenues to finance further growth.

A differentiation strategy is evident when an organization offers products or services with unique features that cost less for it to provide than the extra price that customers are willing to pay for the features. There are numerous ways an organization might differentiate its product or service from that of its rivals, such as exceptionally high quality, extraordinary service, creative design, unique technical features, and generous warranties. The differentiation must be significant enough that customers are willing to pay a higher price. A good example of differentiation is the lifetime service guarantee on Patek Philippe watches, which are built according to standards that go beyond even the strict specifications of the Geneva Seal. The firm’s reputation enables it to charge tens of thousands of dollars for its watches.[55]

Porter also notes that it is important for managers to decide whether their strategy will have a narrow or a broad focus. Focus strategy describes the portion of an overall market that an organization is targeting to serve. A narrow focus strategy means choosing a small segment of the overall market, such as a specific geographic area or a specific kind of customer. For example, managers of a local pizza restaurant must decide whether to distribute flyers throughout the city or only in their neighborhood, whether to create an ambiance that appeals to a broad cross section of customers or to a particular sub-group (e.g., families vs. college students), which items to offer on the menu (e.g., pizza made from organic-only products), and so on. The focus strategy may be combined with either differentiation or cost leadership.

A dual strategy is evident when an organization combines both a cost leadership and a differentiation strategy. Although Porter is skeptical about the wisdom of such a strategy, others have argued that it is entirely possible to achieve. Indeed, even one of Porter’s own examples of a cost leader strategy, Ivory soap, also has elements of a differentiation strategy (Ivory soap is 99.44 percent pure).[56]

The TBL Approach to Generic Strategies

Generic strategies like cost leadership and differentiation may help to optimize an organization’s financial bottom line, but they do little to optimize its social and ecological performance. Moreover, when an FBL organization uses a cost leadership strategy, it may find that it can reduce its financial costs by creating negative socio-ecological externalities. Michael Porter has recognized this problem and tweaked his approach to encourage practitioners to adopt an approach consistent with TBL management that seeks to create shared value that addresses the socio-ecological crises facing humankind.[57]

A TBL cost leadership strategy is evident when an organization has lower financial costs than its rivals, thanks to reductions in its ecological and/or social negative externalities, thereby contributing to its financial well-being. In recent years, Walmart has adopted a TBL cost leadership strategy by reducing its use of fossil fuels (e.g., by using a more fuel-efficient fleet of trucks, using LED lighting in its stores) and minimizing packaging; these actions reduce both its financial costs and its negative ecological externalities. Going further still, Costco—which employs a similar TBL cost leadership strategy in terms of reducing packaging materials and using solar energy—is the only member of the 180 major US companies that comes close to paying its workers a living wage.[58] As former Costco CEO Craig Jelinek observed: “I just think people need to make a living wage with health benefits . . . It also puts more money back into the economy and creates a healthier country. It’s really that simple.”[59]

A TBL differentiation strategy is evident when an organization offers products or services with socio-ecological benefits that cost less for it to provide than the extra price that customers are willing to pay for them. For example, thanks to a being able to charge a higher markup for their produce, organic farmers are generally more profitable than conventional farmers.[60] Whole Foods became a leading grocer by offering organic foods to consumers, and helped to grow the larger organic eco-system.[61] TBL generic strategies can have a broad or a narrow focus, and it is possible to pursue a dual TBL strategy that combines TBL cost leader and TBL differentiation.

The SET Approach to Generic Strategies

The SET approach uses two qualitatively different generic strategies: minimizer and transformer.[62] A minimizer strategy is evident when an organization minimizes negative socio-ecological externalities while ensuring that it remains financially viable. A minimizer strategy is evident at Seventh Generation, a founding B Corporation. Seventh Generation provides “cleaner and greener” products for household and personal care (ranging from laundry detergent and household cleaners to feminine care products). Founder Jeffrey Hollender is passionate about reducing the negative socio-ecological externalities created by business. The desire to minimize externalities is evident in the firm’s product development standards, ingredients, and transportation choices. It reduces waste, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and has eliminated the use of toxic materials.[63]

Glimpses of a minimizer strategy are often evident in the TBL cost leadership strategy. However, unlike the TBL cost leadership strategy, the minimizer strategy is not limited to reducing only negative externalities where that would enhance an organization’s financial well-being. Consider the explanation Bill Gates gave for why millions of children have died of diseases even when medication costs less than one dollar per person. He suggested that it is not in the financial interest of FBL and TBL companies to do anything to save the children: “The market did not reward saving the lives of these children, and governments did not subsidize it.”[64] In other words, firms can make more money doing other things than helping these children. The increased flexibility that SET organizations enjoy precisely because they do not need to maximize profits gives them greater latitude to enhance value creation in areas of ecological and social well-being (e.g., helping the socially marginalized) that would not be considered profitable enough by FBL and TBL firms.

A transformer strategy is evident when an organization creates positive externalities, often by adding value to resources that were previously underappreciated or wasted. A transformer strategy is apparent, for example, in an organization that recycles tires and uses them to make rubber mats, stepping stones, parking curbs, and rubber mulch.[65] A transformer strategy is also evident in volunteer agencies that encourage senior citizens to volunteer in after-school programs that help children with reading difficulties. And it is evident when businesses like ECHOstore and Coffee for Peace (Chapter 5) transform undervalued human and natural resources into vehicles for empowerment, economic security, and peace.

A compounder strategy is evident when an organization simultaneously follows both a minimizer and a transformer strategy, both reducing negative externalities and enhancing positive externalities.[66] In fact, many organizations that have primarily a minimizer or a transformer strategy will also have elements of the other. A compounder strategy is evident in an organization like Habitat for Humanity, which transforms construction waste via its ReStores and transform lives by working with people who otherwise would not be able to afford it build or renovate their own homes (see Chapter 11). Another example is Greyston Bakery (Chapter 1), which hires and trains chronically unemployable people such as the homeless and ex-convicts, thereby enabling them to become valued contributors to society.[67] And it uses fair trade ingredients—including chocolate, vanilla, and sugar—to ensure that producers of these ingredients earn a living wage and use ecologically responsible agricultural practices that enhance the well-being of the soil. Firms can work together in community to implement a compounder strategy; this allows them to create value together that they would not be able to create independently.[68] Glimpses of this can also be seen in the industrial ecological community in Kalundborg, as highlighted in Figure 8.2, where different organizations transform each other’s “waste” into valuable inputs, significantly minimizing waste and converting it into valued resources.[69]

8.5.2. Strategies for Diversified Organizations

Our analysis thus far has looked at individual organizations that operate in a single industry. When such organizations are owned and governed by a larger, diversified parent organization they are called strategic business units. A diversified organization competes in more than one industry or sector, or serves customers in several different product, service, or geographic sectors. Often each separate division in a diversified company is treated as a strategic business unit (SBU) that has its own mission statement, industry, products and services, business-level strategy, and financial statements. For example, the Clorox company has about $7.5 billion in revenues from forty different brands in its “family” in a variety of industries, including Brita (water filters), Hidden Valley (food), and Kingsford (barbecues).[70] Corporate-level strategy determines the combination of industries in which a diversified organization will have an SBU.

While large corporations often diversify their operations to compete in a number of different industries, smaller organizations may face similar issues. For example, a small-scale vegetable farm may sell fresh produce at a farmers’ market, provide specialty produce to local grocery stores, sell farm-fresh salsa via the internet, provide a consulting service to other farmers or consumers, and rent out equipment and services to neighboring farms. The farm might also decide to enter industries that offer year-round income (e.g., jams and pickled watermelon) to offset the seasonality of fresh produce. As another example, Habitat for Humanity has a division to build homes, another to operate its ReStores, another to purchase land, and another to manage mortgage payments. Each of these divisions operates as a separate SBU.

In deciding what sort of diversification they want, managers can choose between two basic types of strategies: (1) related, and (2) unrelated. Related diversification means expanding an organization’s activity into industries that are related to its current activities. ECHOstore illustrates related diversification in its tri-concept model, which integrates retail (ECHOstore), food service (ECHOcafe), and sustainable agriculture (ECHOmarket). This integrated approach allows the company to create multiple revenue streams while maintaining consistency with its core mission of promoting sustainable lifestyles. Related diversification can be further divided into two types: horizontal integration and vertical integration. Horizontal integration is evident when an organization’s services or product lines are expanded or offered in new markets. This happens when a firm buys competitors in the same or similar markets that operate at the same level of distribution (i.e., retail level or manufacturing level). For example, Bauer Performance Sports, a manufacturer of hockey sticks, horizontally integrated by acquiring Easton, which manufactures baseballs.

Vertical integration occurs when an organization produces its own inputs (upward integration) or sells its own outputs (downward integration). Managers facing strong supplier power may purchase a supplier (upward integration), while managers facing strong buyer power may purchase the buyer (downward integration). Major oil companies, for example, have grown through upward integration by getting involved in oil exploration, extraction, transportation, and refining operations. They have also grown through downward integration by operating retail gas stations.

The second type of diversification strategy, unrelated diversification, occurs when an organization grows by investing in or establishing SBUs in an industry unrelated to its current activities, as Clorox has done. Sometimes an unrelated diversification strategy is chosen to reduce a threat identified by a SWOT analysis. For example, managers may diversify if they believe that their current industry is in danger of declining, or if they believe diversification is critical to sustain growth. With the purchase of Burt’s Bees (a company whose personal care products are environmentally friendly), Clorox gained opportunity to learn about sustainable business practices while offsetting its image of being a company that promotes use of bleach, which can be ecologically harmful.[71]

Of course, sometimes diversified organizations choose to reduce their involvement in some industries, which is called retrenchment. Divestment refers to the process of decreasing the number of industries in which a diversified firm operates an SBU. Portfolio management tools have been developed to help managers of conglomerates—diversified organizations with SBUs in unrelated industries—to develop their corporate-level strategy and decide which industries to remain active in, which to enter, and which to divest from. Similar to individual investors who seek to diversify their personal financial investments, managers in conglomerates look for an optimal mix of types of SBUs and industries in which to operate. Consider the following two portfolio matrices, one associated with FBL management, and the other more relevant for TBL and SET approaches.[72]

Conventional Portfolio Matrix Based on FBL Management

Perhaps the best-known FBL tool for business portfolio planning was developed by the Boston Consulting Group and is called the BCG matrix, which classifies each SBU according to (a) its market share, and (b) the rate at which its industry is growing (see Figure 8.3).[73]

Figure 8.3. BCG portfolio matrix for managing diversified organizations

Market share refers to the proportional sales a particular SBU has relative to the entire industry. An SBU that enjoys a 10 percent or greater share of the market in its industry is rated as being high.[74] The market growth rate refers to whether the size of a particular market is increasing, decreasing, or stable. This is an indicator of an industry’s strength and future potential. An annual growth rate of 15 percent or more is considered high.

Dichotomizing each of the two basic dimensions of the BCG matrix yields four types of organizations. A star enjoys a high market share in a rapidly growing industry.[75] Like movie stars, such businesses generate a lot of cash but also need a lot of cash to add the additional capacity required to keep growing. A star has a high profile and promises to generate profits and positive cash flows even after the growth of the industry stabilizes. Within the portfolio of Apple, iPhones have long been a star, enjoying a strong market share in what has been a growing industry.[76] However, as the industry growth levels off, the iPhone will turn into a cash cow.

A cash cow enjoys a high market share in a low growth or mature industry. Within Apple’s portfolio, the iTunes Store can be considered a cash cow, thanks to occupying 60 percent of the market share in its industry, but the industry itself has not been growing.[77] BCG suggests that cash cows should be “milked” and the profits invested in other SBUs within the portfolio that are stars or question marks.

A question mark has a low market share but operates in a rapidly growing industry. A question mark presents a difficult decision for management, as the risk of no return on the investment is very real. In the end, only those question marks with the most likely chance of success should be invested in. For example, Apple’s attempt at introducing a product like Apple TV, while enjoying some level of success, is still a question mark in terms of whether it will become a star in the growing market of alternative television service providers.

Finally, a pet has a low market share in a low growth industry. Pets typically produce little or no profit and have little potential to improve in the future.[78] Pets should be sold off if a turnaround is not possible, unless the pet offers synergies with other products. Synergy occurs when the performance gain that results from two or more units working together—such as two or more organizations, departments, or people—is greater than the simple sum of their individual contributions. The owner of a large vegetable farm may not earn much profit operating a stand in a farmers’ market but may continue to do so if this helps to gather information about consumer purchasing trends. In Apple’s portfolio, the iPod ran the full cycle in the BCG, starting off as a question mark, becoming a star, then a cash cow, and then a pet before being discontinued in 2022.

The strength of the BCG matrix is that it helps managers make strategic decisions by focusing on two important and practical dimensions. It also offers a simple conceptual framework to think about portfolio decisions for managers, about which industries or product lines to enter and to exit, and about how to transfer profits earned by a product or SBU in one quadrant (e.g., a cash cow) into another SBU in a different quadrant (e.g., a star or a question mark).[79]

An Alternative Portfolio Matrix Based on TBL and SET Management

From a TBL or SET perspective, a significant weakness of the BCG portfolio matrix is its total disregard of issues related to socio-ecological well-being. This shortcoming can be addressed by developing a parallel framework that is relevant for TBL and SET managers (see Figure 8.4).[80] The vertical dimension is sustainable development, which assesses how effectively an industry reduces its socio-ecological negative externalities. Negative externalities are reduced when car manufacturers transition from gasoline to electric cars, and when travel agencies transition from promoting overseas travel to staycations.

Figure 8.4. A TBL/SET approach to a corporate strategy portfolio matrix

The horizontal dimension, restorativeness, considers how effectively an industry creates positive socio-ecological externalities. A high level of restorativeness is evident in industries where organizations enhance the socio-ecological well-being of their stakeholders. For example, an industry will score high in ecological restorativeness if it takes carbon out of the atmosphere and uses it to enrich the soil (e.g., conservation agriculture). An industry scores high in social restorativeness if it enhances mental health (e.g., Big Brother/Sister organizations, national parks, and retreat centers).

Dichotomizing these two dimensions—sustainable development and restorativeness—yields four types of organizations. A sustainability hero minimizes negative externalities (high sustainable development) and enhances positive externalities (high restorativeness). An example of an ecological sustainability hero is an organization that provides curbside composting services. Rather than organic waste being thrown into landfills, where it may contribute to methane gas release, the waste is composted and returned to the soil, where it provides nutrients to grow healthy food. An example of a social sustainability hero is a seniors’ center where retired people (who are looking for meaningful things to do) can participate in physical activities and adult education, or in after-school programs that help young children with reading difficulties. Such industries should be encouraged and receive investment, and the lessons learned and practices developed in these industries transferred to others.

An innocent bystander has high sustainable development but low restorativeness. For example, industries related to renewable energy or electric cars are designed to reduce GHG emissions but may do little to restore existing waste. However, restorativeness could be added if, for example, a source of electricity or an automobile engine were developed that was powered by carbon dioxide (mimicking photosynthesis). Managing to add restorativeness to an innocent bystander can transform it into a sustainability hero.

A fragile player creates both positive and negative externalities. For example, the Children’s Wish Foundation provides trips to Disneyland for children with life-threatening illnesses. This provides positive social externalities (joy and respite for the families) but also creates a negative ecological externality (the pollution that is generated by the air travel). Managers could try to create substitute products and services (possibly from other industries) that create similar positive externalities but reduce negative externalities. For example, rather than fly a family to Disneyland, they could be treated at a local resort or amusement park. Managing to increase sustainable development in a fragile player can transform it into a becoming sustainability hero.

Finally, lavish actors are low on both sustainability and restorativeness. Lavish actors represent great opportunities for positive change, either from within or by being rendered. For example, like other firms in its industry, the Statoil oil refinery in Kalundborg at one time created negative ecological externalities while doing little to transform the waste of others. Then managers at the refinery started to utilize “waste” steam from the coal plant. They also improved their refinery’s filtering process to emit less wasteful sulfur gas and instead provided sulfur inputs valued by neighboring companies. However, it might be even better if the oil refinery were made obsolete by using its profits to invest in advances in, say, solar energy.

Using an alternative matrix like this—instead of the conventional BCG portfolio matrix—provides a very different frame of reference for choosing which industries to enter, how to move funds from an SBU in one quadrant to an SBU in another, and what sorts of products to invest in or bring to market. This matrix can also be used in non-business organizations. For example, imagine what would happen if governments used the matrix—with its explicit attention on sustainable development and restorativeness—to make decisions about social procurement and the services they provide with respect to waste removal, caring for seniors, education, health care, and so on. That could unleash powerful forces to increase the sustainability of how we live.

Test Your Knowledge

8.6. Entrepreneurial Mission and Vision

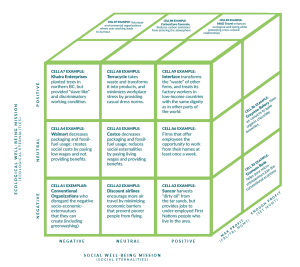

When it comes to formulating a strategy, the first step and perhaps most important decision facing entrepreneurs is related to the start-up’s mission and vision. As shown in Figure 8.5, we can think of about eighteen potential types of entrepreneurial start-ups based on how their mission relates to financial, social, and ecological well-being. Taking the time to think about the mission and vision of their start-up in financial, social, and ecological terms—and in particular how these matters align with the entrepreneurs’ own personal values and beliefs and reasons for being an entrepreneur—can help entrepreneurs to develop the kind of organizations that will heighten their sense of motivation and satisfaction. We will briefly discuss each of the three dimensions in Figure 8.5.

Figure 8.5. Eighteen types of organizations, based on their mission

8.6.1. Financial Well-Being

Consistent with the difference between acquisitive economic goals (FBL and TBL entrepreneurs) versus sustenance economic goals (SET entrepreneurs), an organization’s mission can be described in terms of how it approaches financial well-being. This difference is shown in the “depth” dimension of Figure 8.5, which contrasts those organizations whose mission is to maximize financial well-being in the front part of the figure (associated with FBL and TBL approaches) with organizations that seek to make enough profit (SET approach). (Note that cells B1, B2, B4 and B5 are not shown in Figure 8.5).

8.6.2. Ecological Well-Being

The vertical dimension describes an organization’s mission regarding ecological well-being, which can be negative, neutral, or positive. Of course, no organization would specifically set a goal to damage the environment, but negative ecological value creation nonetheless occurs when the environmental costs that an organization creates (e.g., clean-up costs associated with its waste and pollution) are not reflected in its planning or calculations. Managers may be tempted to sacrifice ecological well-being when other types of well-being are considered more important. For example, recall that the world’s 1,200 largest businesses created about $5 trillion of negative ecological externalities in 2018, largely because they prioritize financial well-being (Chapter 1). Likewise, some of the businesses operated by micropreneurs who receive microcredit from financial institutions like the Grameen Bank may create pollution and thus have a negative effect on ecological well-being (but a positive effect on social well-being).[81]

Neutral ecological value creation involves situations where harm to ecological well-being is reduced or eliminated, though nothing is done to improve ecological well-being. This type of mission may be pursued by two kinds of organizations. The first are TBL organizations that strive to become “less bad” by decreasing the ecological damage they create through “sustainable development.” Examples include firms such as Walmart’s and Costco’s efforts to decrease pollution through solar panels and reduced packaging use (cells A4 and A5 in Figure 8.5). The second type of organization in this category would be SET organizations that prioritize social well-being more highly than ecological well-being. Consistent with their SET management approach, these organizations recognize the importance of the natural environment and therefore avoid damaging it; however, most of their effort is devoted to addressing social outcomes rather than increasing ecological well-being. For example, Velo Renovation (opening case, Chapter 9; cell B6 in Figure 8.5) has some initiatives that reduce ecological externalities, but most of the positive externalities it creates involve social well-being.

Finally, positive ecological value creation arises from firms that make enhancing ecological well-being part of their mission. ECHOstore (cell B9) demonstrates this commitment to positive ecological value creation through multiple initiatives. Its careful curation of eco-friendly and organic products, support for sustainable farming practices, and promotion of transformer circular economy principles through its integrated farm operations all contribute to environmental enhancement rather than just harm reduction. Interface Industries is also well-known for its mission to generate net-positive ecological externalities, a challenge its late CEO Ray Anderson likened to climbing higher than Mt. Everest (opening case, Chapter 13; cell B9). For example, Interface has paid villagers in the Philippines to collect, clean, and bale over 100 tonnes of discarded fishing nets to be recycled into new carpet fiber.[82]

8.6.3. Social Well-Being

The horizontal dimension of Figure 8.5 considers an organization’s mission regarding social well-being. Along this dimension, negative social value creation results when the organization’s activities worsen social well-being. As with negative ecological value creation, this harm is typically not intentional, but the lack of intention does not reduce the harm. For example, negative social externalities arise when businesses in high-income countries seek to minimize their financial costs by choosing suppliers in low-income countries based only on price, without regard for the working conditions in those suppliers. Negative social externalities can also arise when an organization seeks to maximize profit at the expense of workers or communities. Likewise, some organizations may pursue financial and ecological well-being with such zeal that a social cost is created. Khaira Enterprises, a tree-planting business in British Columbia, is an example of how a firm can enhance ecological well-being but produce negative social externalities (Figure 8.5, cell A7). Khaira was ordered to pay $700,000 in damages for the abusive, discriminatory, and “slave-like” working conditions it forced on its workers.[83]

Neutral social value creation results when firms succeed at being less bad but do not focus on being better. For example, organizations may seek to reduce negative aspects of social well-being either internally (e.g., designing jobs that cause less stress or reduce physical hardship for employees) or externally (e.g., making their goods available to more people). But they may still pay less than a living wage, and they may be increasing indebtedness of consumers.

Firms that aspire to create positive social externalities are often associated with SET management. This might happen, for example, when a firm hires ex-convicts in order to provide them the opportunity to become better contributors to society and thereby increases the likelihood that these employees stay out of prison (e.g., Greyston Bakery, cell B9).

Once entrepreneurs have thought deeply about the mission and vision of their start-up, they will have gone a long way toward identifying what sorts of strengths are needed, what sorts of opportunities should be pursued, and what sort of strategies are most relevant.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Managers follow a four-step process to formulate strategies:

- (i) establish the organization’s mission and vision;

- (ii) identify the strengths and weaknesses of the organization’s resources;

- (iii) identify key opportunities and threats in the external environment; and

- (iv) develop the chosen strategy.

- When establishing the organization’s mission and vision,

- FBL managers focus on financial well-being and a competitive strategy, using a top-down process;

- TBL managers focus on the triple bottom line and a competitive strategy, using a mostly top-down process;

- SET managers focus on socio-ecological well-being and a collaborative strategy, using broad participation among a variety of stakeholders.

- When analyzing internal resources to identify strengths and weakness, managers pay attention to the resources’ value, rarity, inimitability, and non-substitutability (VRIN).

- When analyzing external factors to identify opportunities and threats, managers pay attention to the following five forces: supplier power, customer power, substitutes, threat of new entrants, and intensity of rivalry.

- When developing generic strategies for competing within an industry,

- FBL managers choose a cost leadership or differentiation strategy;

- TBL managers choose a TBL cost leadership or TBL differentiation strategy;

- SET managers choose a minimizer or transformer strategy.

- When managers of diversified organizations consider portfolio matrices, FBL managers consider market growth and market share, TBL managers are more concerned about sustainable development, and SET managers are most likely to consider restorativeness.

- Entrepreneurs can choose from eighteen different types of missions, depending on their priorities in terms of financial well-being (maximum profit vs. enough profit), social well-being (negative, neutral, positive), and ecological well-being (negative, social, positive).

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Go online and find the mission and vision statements of three organizations, including one that seems to be managed from an FBL approach, another from a TBL approach, and a third from a SET approach. How consistent (or inconsistent) are these mission and vision statements compared to the nine elements described in this chapter (Table 8.1)? How do they compare to each other?

- Choose an organization you are familiar with (e.g., your current employer, or where you would like to work in the future) and analyze its mission and vision statements in light of the material covered in this chapter. Identify their strengths and weaknesses, and suggest how they could be improved.

- Think of an industry where most of the leading firms take an FBL approach to management. Imagine that you prefer a TBL approach. Use concepts from this chapter to think about how you would go about developing a strategy to enter this industry.

- Develop a new alternative portfolio matrix that has two dimensions that you personally feel are important but are different from the dimensions presented in this chapter (i.e., your matrix should differ from those shown in Figures 8.3 and 8.4). Try to find examples of organizations in each quadrant of your new matrix.

- Now that you have read the chapter, use the concepts you have learned to analyze the opening case. Based on what you have learned, what advice would you have for the managers? If you were asked to suggest a formal mission statement and a formal vision statement for ECHOstore, what would you suggest?

- Write a mission and a vision statement for your professional life. What is your ongoing mission, and what is your vision for five or ten years from now?

- Write a mission and a vision statement for your personal life. How much overlap is there between your professional and personal statements? Which set of statements has more influence over the kind manager you want to become?