Part 1: Background and Basics

5. Management and Social Well-Being: Meaningful Work, Meaningful Relationships, and Peace

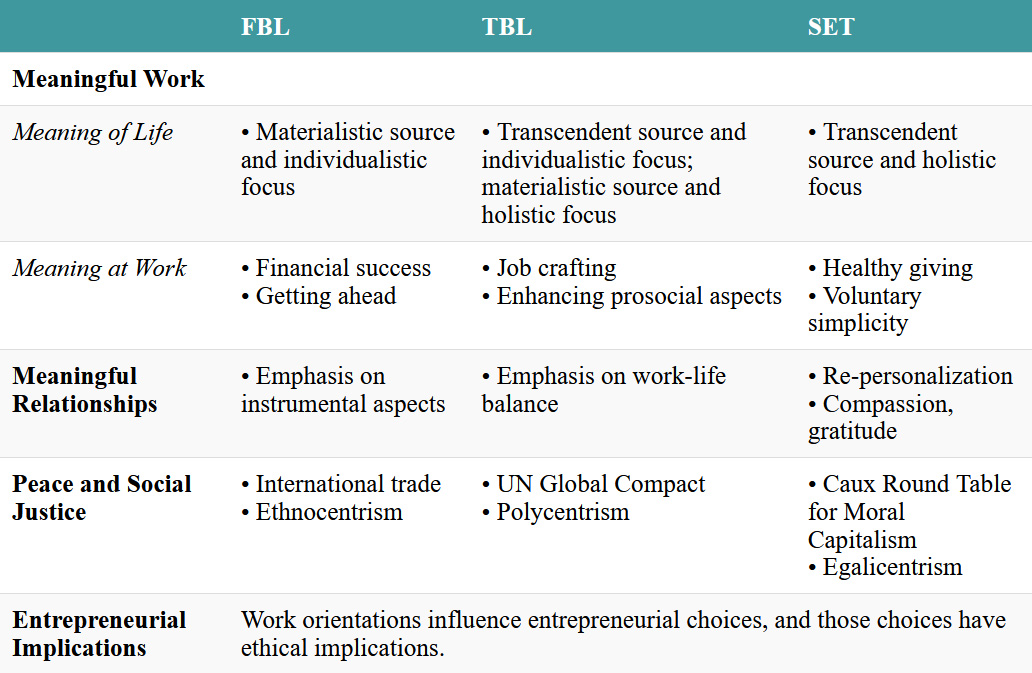

Chapter 5 provides an overview of three key components of social well-being—meaningful work, meaningful relationships, and peace and social justice—as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the three key dimensions of social well-being: meaningful work, meaningful relationships, and peace.

- Explain how the three key dimensions of social well-being are managed in FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

- Describe how different assumptions about the source of meaning (transcendent vs. tangible) and the focus of meaning (individualistic vs. holistic) produce a framework that describes four different views of the meaning of life.

- Explain the difference between instrumental and non-instrumental relationships.

- Describe how businesses can undermine or foster peace.

- Describe three different work orientations and how they influence entrepreneurship.

- Consider the well-being implications of entrepreneurial choices.

5.0. Opening Case – Being Boldr: Placing Social Well-Being at the Core of Business

In 2016, David Sudolsky faced a profound turning point in his life and career when his best friend and business colleague, Jeff Bauer, passed away unexpectedly.[1] This loss prompted Sudolsky, then in his twenties, to deeply reflect on the legacy he wanted to leave. Having spent several years helping companies build global teams, he had witnessed firsthand how the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry—that is, businesses a firm might hire to do its accounting, human resource management, or information systems management—often prioritized profits over people, creating what he saw as a “race-to-the-bottom” mentality that compromised worker well-being for financial gains.

“I started Boldr with a single-minded desire to redefine ‘outsourcing’ in a way that added more to society than it took,” Sudolsky explains.[2] This was the vision behind the founding of Boldr in 2017 as a company that would challenge traditional BPO practices by placing social well-being at the core of its business model.

From its inception, Boldr’s approach to meaningful work has differed markedly from industry norms. Rather than view employees as mere “human resources” to optimize for productivity, Boldr’s policies and practices emphasize personal growth and fulfillment. This includes, for example, inviting employees to help co-create programming that helps their larger community, including what Sudolsky describes as “getting kids off the street and back into schools . . . You know, I used to think that I had all the answers but then I realized that . . . the best ideas come from this dialogue that we have with the people around us.”[3] The company’s commitment to meaningful work is evident in its remarkable 90 percent retention rate among team members supporting e-commerce and software-as-a-service (SaaS) clients, significantly higher than industry averages. As part of empowering employees and providing meaningful work, Boldr ensures that team members can see clear paths for growth, and it became the first BPO in the Philippines to formally implement a living wage policy, eventually extending this commitment across all its global operations. “A living wage makes a huge difference especially compared to our previous salaries,” shares Marlene Tabla from Boldr Manila’s Office Operations team. “Every time the prices of goods increase, the minimum wage will never be enough for making ends meet. That is why living wage adjustment is an important move and I hope all the companies choose to do the same.”[4]

Boldr’s emphasis on peace and social justice is perhaps most evident in its approach to global expansion. Rather than simply seeking locations with the lowest operating costs, Boldr has deliberately established operations in communities where it can make significant social impact and has partnered with fifteen organizations across the Philippines, South Africa, and Mexico to provide digital skills training to disadvantaged individuals. In South Africa, for example, where youth unemployment exceeded 60 percent, Boldr opened its BPO Academy in the town of Hazyview to provide digital skills training and employment opportunities.

The company’s commitment to meaningful work and to fostering social justice is also evident in its community engagement initiatives. Boldr’s team members have contributed over 7,500 volunteer hours to various community projects, ranging from providing internet connections for schools to organizing food fairs and supporting disaster relief efforts. In 2021, Boldr’s commitment to social well-being received formal recognition when it became a B Corp–certified company—the first global Employment of Record company to achieve this certification. Boldr allocates 1 percent of its quarterly revenue to community organizations and charitable partners globally.

Boldr’s focus on social well-being has not prevented it from enjoying business success. By 2023, the company had grown to serve over 100 clients across North America, Europe, and Australia, with more than 1,500 team members across five countries. This growth earned Boldr recognition on the Inc. 5000 list of fastest-growing private companies for three consecutive years. Yes, Boldr may have enjoyed higher profits if it had paid its employees the going rate instead of a living wage, and if it did not donate 1 percent of its revenues to charity. But then it would not have satisfied Sudolsky’s sense of calling to be a transformative force in the outsourcing industry, nor would it have created such meaningful work for 1,500 people!

In sum, Boldr demonstrates how businesses can go beyond aspirational goals and actually achieve meaningful employment, authentic relationships, and positive social impact—truly a legacy to be proud of.

To learn more about Boldr’s journey, listen to the video podcast Building a Mission-Driven BPO: The Story of Boldr Impact,[5] at https://youtu.be/3yRQJK53iUA?si=vOq18bUXj0HJa_wP

5.1. Introduction

Whereas focusing on individual well-being and financial success is a hallmark of Financial Bottom Line (FBL) management, enhancing social well-being is one of the three pillars of Triple Bottom Line (TBL) management and one of the two fundamental goals of Social and Ecological Thought (SET) management. Managers have known about the importance of social well-being since at least the human relations era (see Chapter 2), and subsequent research has confirmed that attending to the social well-being of employees can increase their motivation and productivity, and thus an organization’s financial well-being. However, as illustrated by Boldr, a fuller understanding of social well-being goes much deeper than tactics to improve productivity and profits.

In this chapter, we lay the foundation for understanding social well-being. We will return in later chapters to look in more detail at many of the themes related to social well-being, such as leadership, motivation, groups, and teams. Here we will consider three fundamental components that contribute to social well-being: meaningful work, meaningful relationships, and the opportunity to work in environments that are characterized by and foster peace and social justice.[6]

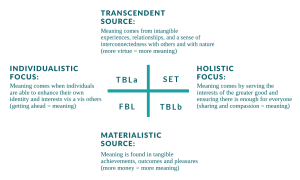

5.2. Meaningful Work

To understand what makes work meaningful, it is helpful to think first about what makes life meaningful. Questions about the meaning of life have been pondered for millennia, but there is still no universally accepted understanding of what makes life meaningful. In part this may be because finding meaning in life is shaped by our context and environment. Since the context and environment of humankind has changed a lot over time (from hunter-gatherer to postmodern societies), the way we think about meaning in life is also changing. Even so, as depicted in Figure 5.1, two dimensions are helpful for thinking about a meaningful life: the source of meaning (transcendent vs. materialistic), and the focal point of meaning (individualistic vs. holistic).[7]

Figure 5.1. Two key dimensions related to meaning in life

Regarding the source of meaning in life, Western society has emphasized a materialistic understanding for the last couple of centuries. Calling an organization or manager “successful” typically suggests that they have achieved financial well-being (note that the word “success” refers to the accomplishment of a desired or meaningful end). It assumes that money is the goal that everyone desires, an idea closely associated with materialism. As noted in an Chapter 2, this definition of success is relatively recent in the history of humankind, as money itself is less than 4,000 years old. Even so, philosophers consider today’s emphasis on the meaningfulness of money as a hallmark of our society, one that often gets in the way of other longer-standing and intangible understandings of a meaningful life.[8]

In contrast to focusing on materialistic sources, in a transcendent understanding understanding of meaning people see themselves as connected to an entity that is greater than or beyond themselves, and meaning is related to deliberately acknowledging this larger entity.[9] A transcendent understanding can include the sense of well-being—which may be experienced as peace or happiness or fulfillment—that comes from feeling deeply connected to other people or to nature. Transcendent understandings are most transparent in management theory and practice in the “spirituality at work” literature, where spirituality is defined as a sense of interconnectedness with others, nature, and a sacred other.[10] Even in Western materialistic societies, 80 percent of college students have shown an interest in spirituality, and almost half (48 percent) have indicated that it is “very important” or “essential” that their college encourage their personal expression of spirituality.[11] Meanwhile, research among university students in China has shown spiritual well-being to explain 70 percent of the variance in psychological health (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress).[12]

Regarding the focal point of meaning, Western society places a strong emphasis on an individualistic understanding of meaning. According to this perspective, people and organizations become successful by out-competing others, by pursuing their own self-interests and values, and by getting ahead.

This individualistic focus is also relatively recent in the history of humankind, whose self-understanding has in the past generally been based on holistic and communal philosophies like Ubuntu: “I am because I belong.” Here the emphasis is on enhancing the greater good; for example, by bettering the lot of people who live in socio-economic conditions that make them unable to feed their families or provide education for their children.

5.2.1. Where We Acquire Our Understanding of Meaning

What we perceive to create meaning in life is greatly influenced by socio-cultural factors in our external environment, including the family values in our childhood home, our understanding of morality and ethics,[13] the messages about success embedded in the media, our organizational role models and mentors, and the culture and values in the countries where we live. With respect to ethics and morality, for example, your understanding of what is meaningful will be informed by your level of moral development. You may be pre-conventional (“What’s in it for me?”), conventional (“How can I fit in with what are the people around me are doing?”), or post-conventional (“What are the timeless truths?”).[14] Your views also will be influenced by whether you believe ethics are established by a deity, or whether you think they can be derived from observing natural interactions, or both. The first chapter of this book describes how variations of a consequential utilitarian moral point of view underpin FBL and TBL approaches, and how a virtue ethics perspective underpins SET management.

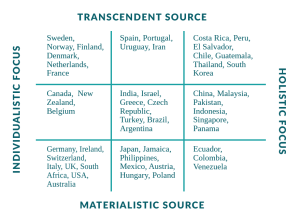

For an example of how national cultures and values shape people’s views of the meaning of life and work, Figure 5.2 shows where countries have been ranked (high, medium, and low medium, and high) in their relative emphases on the two key dimensions related toshown in Figure 5.1: transcendence versus materialism, and individualism versus a holistic focus .[15] As might be expected, countries that rank high in both materialism and individualism—like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia—are precisely the ones where FBL management theory and practice has been the most developed. On the other hand, we would expect to see management practices more aligned with SET management in countries that are highly ranked for holistic focus, like Costa Rica and Peru. Consistent with this expectation, Costa Rican managers are five times more likely to prefer a management style where they consult with and invite members to participate in decision-making, rather than following a style based on managerial authority and persuasion.[16] Similarly, it is not unexpected that Costa Rica was named “UN Champion of the Earth” for its important role in combating climate change,[17] that it is seen as a world leader in using ecotourism (which promotes natural attractions while minimizing visitors’ ecological impact) as a strategy for economic growth,[18] and that it is a leader among low-income countries in environmental programs[19] (to the point where one study suggested that its forest stock is “sub-optimally large” [20]). More generally, in a study that compared 178 countries according to how well people were able to live long, happy lives with minimal impact on the natural environment, Costa Rica ranked in the top three.[21]

Figure 5.2. Relative emphasis (high, medium, low) in different countries on a materialistic vs. transcendent versus materialistic source and an individualistic vs. holistic dimensions focus

As might be expected, thanks to a materialist-individualist emphasis on maximizing productivity and financial well-being, the US GDP (gross domestic product) per capita is almost five times greater than that of Costa Rica.[22] It also takes about 7.8 global hectares of natural resources to sustain the lifestyle of the average American, which is almost five times greater than the 1.6 global hectares for the average Costa Rican.[23] Interestingly, the self-reported life satisfaction scores for people in the United States (6.72) and Costa Rica (6.96) are similar.[24] The same holds true for life expectancy scores, with the United States at 80.9 years and Costa Rica at 80.3 years.[25] In other words, the average Costa Rican and the average American live equally satisfying lives, even though the average Costa Rican consumes far fewer resources (21 percent of the average American consumption) and has a lower per capita GDP (20 percent of the average American).

5.2.2. Hallmarks of Meaningful Work

Meaningful work enhances the meaning of life for those doing the work.[26] Because people spend so much time at work, it becomes a primary source of their purpose, identity, and belonging.[27] For decades, Americans have said that meaningful work is more important to them than income, job security, and promotions.[28] In one study almost two-thirds of millennials said that they would rather earn $50,000 a year in a job they love than $130,000 a year in a job that they find boring.[29]

Meaningful work influences many of the most important outcomes identified in organizational studies, including job performance, job satisfaction, work motivation, engagement, absenteeism, empowerment, stress, organizational commitment and identification, and customer satisfaction.[30] According to the literature, work is more meaningful for people who

- experience a fit between their job and their sense of purpose/true self (i.e., their job is consistent with what they perceive to be the meaning of life);

- believe that their work gives them power and opportunity to make a positive difference in the world; and

- feel valued and a sense of belongingness in their workplace.[31]

Work that is not meaningful may lead to depression, decreased psychological well-being, lower self-esteem, poorer resilience to burnout,[32] and higher risk of suicide.[33] Unfortunately, work-related issues associated with low levels of psychological health are increasing. Depression and anxiety disorders are the leading cause of sickness, absence, and long-term work incapacity in most developed countries.[34] For example, the economic burden due to major depressive disorder in the United States in 2018 was $326 billion (an increase of $90 billion since 2010). On average, this is about $1,000 per person in the United States. The workplace share of these costs increased from about $115 billion in 2010 to $200 billion in 2018 (especially due to absenteeism, with over 300 million lost workdays per year).[35] A 2023 Gallup poll showed that about one-third of workers were somewhat or completely dissatisfied with the stress levels at work.[36] Other research has found that only 17 percent of the global workforce is actively engaged in their work, with most of the workplace stress being caused by dysfunctional managers.[37]

Even small improvements in well-being can have significant effects.[38] For example, on a well-being scale of 1 to 100, compared to an employee who rates themselves at 70, an employee who rates themselves as a 75 has a 15 percent lower risk of depression or anxiety, 19 percent lower risk of having sleep disorders, 15 percent lower risk of diabetes, and 6 percent lower risk of obesity.[39] Moreover, well-being in the workplace may be contagious, so that high well-being for one member of a work team results in a 20 percent increase in likelihood that another team member will be thriving six months later.[40] This suggests that managers who take care of their own well-being will foster well-being in their co-workers.

5.2.3. The FBL Approach to Meaningful Work

FBL management promotes the view that meaning in life is closely connected to individuals and organizations achieving financial success. From this perspective, work is seen as meaningful if it increases productivity, sales, and financial well-being, all of which are hallmarks of the FBL approach. Such a message is promoted in mainstream marketing, which, in terms of dollars, costs more than all the money spent on public education on the planet. Because 75 percent of the advertising that consumers see is paid for by the world’s 100 largest corporations,[41] it should not come as a surprise that the messages promoted in the mass media have been dominated by four key values that are consistent with the FBL approach:

- Happiness is found in having things (materialistic source);

- Get all you can for yourself (individualistic focus);

- Get it all as quickly as you can (short time horizon); and

- Win at all costs (competitiveness).[42]

This message seems to have influenced many people. For example, according to a Gallup poll, in 2023 the average American worked about forty-four hours per week (based on adults employed full-time or part-time),[43] and many would like to work more hours. However, while working long hours may lead to short-term benefits and meaning, in the long term overworking results in increased depression, stress, and poor health.[44] It is noteworthy that FBL management is not the first choice of millennial employees, 88 percent of whom disagreed with the statement “money is the best measure of success.”[45] When management students were asked in which quadrant in Figure 5.1 they would prefer to be managed, only 7 percent chose the FBL quadrant; 50 percent preferred TBL approaches and 42 percent preferred SET management.[46]

5.2.4. The TBL Approach to Meaningful Work

TBL management seeks the financial benefits of providing meaningful work—such as increased performance, motivation, and commitment, and reduced costs due to decreased turnover and stress days—that have been known since the start of the human relations movement (see Chapter 2). As will be described more fully in Chapter 12, TBL management tries to increase meaningful work insofar as it improves an organization’s financial well-being by designing jobs that have task significance (the tasks being performed have a positive impact on other peoples’ lives or work)[47] and by increasing autonomy, skill variety, and task identity (employees can see how their work fits into a coherent whole). These characteristics have been shown to produce meaningful work and improve performance.

TBL management considers social well-being as one of the three pillars of the triple bottom line. In terms of Figure 5.1, management consistent with the TBLa quadrant does this by empowering members to take more control by participating in shaping their work. For example, whereas FBL management emphasizes top-down job design, where managers develop the jobs that shape members’ experience of meaningfulness, TBL management puts greater emphasis on job crafting, where members design their own jobs to be meaningful based on their own experience.[48] Job crafting involves changes to the cognitive meaning of the task (e.g., instead of seeing their job as cleaning up other peoples’ messes, hospital janitors see their job as helping to care for and heal patients).[49] Job crafting also includes adding some choice to the job tasks performed (e.g., how much energy and time is spent on specific subtasks) and the people an employee relates to. Management within the TBLa quadrant is also evident when employers provide mindfulness training and similar programs to help employees manage their workplace stress and improve concentration.[50]

Glimpses of the TBLb quadrant are evident when enhanced prosocial holistic dimensions of work increase the perception that the work is meaningful. For example, workers tasked with phoning university alumni to raise funds for scholarships were more productive and found their work to be more meaningful after they had met students who had received such scholarships.[51] The benefits of a prosocial focus are also evident in terms of the overall vision or mission of TBL organizations, which often seek to improve the social well-being of stakeholders. The transformational leadership literature talks about how performance can be enhanced by inviting employees to share the noble vision of an organization (see Chapter 15). The TBLb quadrant also places greater emphasis on group- or team-based interventions to improve meaning; this includes members actively participating in developing shared work-related goals and action planning (see Chapter 16). These practices have been found to be more effective than focusing on individual employees.[52]

Test Your Knowledge

5.2.5. The SET Approach to Meaningful Work

SET management also supports the value of mindfulness training and job crafting, but the SET approach asks bigger questions about why such stress-reduction is needed in the first place. Rather than instrumentalize mindfulness to serve an organization’s financial well-being, a holistic understanding of mindfulness requires rethinking concepts around how and why we work.[53] From a SET perspective, FBL and TBL understandings of meaningful work are inherently flawed because they link it to increasing financial and material success in a finite world. SET management takes seriously the warning given by Max Weber, who characterized managers who follow FBL and TBL practices as “specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.”[54] A SET approach also acknowledges Adam Smith’s concern that productivity-maximizing practices such as the division of labor would result in workers becoming “as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.”[55]

SET management turns some of the truisms of the FBL and TBL approaches on their head. For example, the SET approach argues that more meaning comes from giving than from taking (see Chapter 14). While it is true that people find their jobs more satisfying the more help they get from co-workers, SET management underscores the idea that people find their jobs more meaningful the more assistance and support they give to others (e.g., finding opportunities to care for, assist, mentor, or support a colleague).[56] Similarly, rather than focusing on meeting the wants of customers, SET management promotes meaningful work that serves the needs of others.

The SET approach is consistent with the growing voluntary simplicity movement, where meaning comes from deliberately working fewer hours and choosing wholesome places to work. It recognizes that social well-being does not come from having more than enough stuff but rather from doing what is meaningful and earning enough money to live.[57] People are increasingly more interested in the quality of life and a sense of community and social equity, than they are in material and economic rewards, prosperity and control.[58] Voluntary simplicity is associated with well-being,[59] and related to the minimalist movement: 11 percent of Americans consider themselves to be minimalists, and another 26 percent want to be or are actively working to become minimalists.[60]

SET management recognizes that management practices that increase the gap between rich and poor people are problematic.[61] Work is more meaningful if it serves the interests of those with insecure incomes, and especially if it promotes and develops structures that enable people who have been marginalized to work to provide for the needs of their families (evident in Boldr’s expansion strategy in South Africa, where it deliberately established operations in communities with high youth unemployment). Even people from relatively wealthy countries are challenging systems they see as unjust, including when those systems serve their own financial self-interests.[62]

Finally, an emphasis on a holistic focus and a transcendent source is evident in the increasing interest in spirituality and religion among management practitioners and scholars.[63] A focus on the material realm is often seen as opposed to a focus on spirituality. Similarly, the self-interested nature of individualism runs counter to the teachings of many religions. Should ideas about spirituality be part of the study of management? The Academy of Management (the world’s largest and most prestigious scholarly association of management) seems open to the idea, given that it has a Management, Spirituality, and Religion division.[64] It seems likely that religious and spiritual worldviews have helped to shape management theory and practice, given that over 80 percent of the people in the world espouse and hold such worldviews.[65] Studies published in 2007 found that three of every five (60 percent) business professors think that the spiritual dimension of faculty members’ lives has a place in their jobs as academics, and one of three (31 percent) think that colleges should be concerned about facilitating students’ spiritual development. Student responses suggest that about two of five that college professors encourage discussion of spirituality (38 percent) and raise questions about the meaning and purpose of life (44 percent).[66]

While these approaches to meaningful work provide a useful framework, it’s important to recognize that the reality is often more complex. Managers should be aware of the nuanced nature of meaningful work and tailor their approaches based on individual employee needs and organizational context. This may involve combining elements from different approaches or developing new strategies that go beyond these categories.

Test Your Knowledge

5.3. Meaningful Relationships

It is noteworthy that when management books or courses talk about interpersonal relationships—be they relationships with co-workers or with suppliers or managers—it is primarily in terms of their instrumental qualities, with an emphasis on how managers can use social skills to increase workers’ motivation and productivity, negotiate a lower price from suppliers, or increase customer loyalty. These are called instrumental skills because they focus on how we can “use” other people the way we use instruments or mechanisms to accomplished something. In contrast, the purpose of non-instrumental relationship skills is to develop and deepen interpersonal connections for their own sake, to share joy and excitement and grief and loss, and to foster love, trust, and mutual acceptance.[67] Surprisingly little discussion or research looks at skills for facilitating non-instrumental friendships with co-workers, suppliers, and customers, whom we encounter in the workplace settings where we spend a large portion of our lives. And yet many people would agree that non-instrumental friendships are crucial to social well-being and a meaningful life.[68]

Awareness of the links between economic activity, friendship, and social well-being dates back to the earliest understandings of economics. For example, Aristotle saw economics as a means to enhance deep happiness (eudaimonia) in community; for him it was dysfunctional for economic activity to instrumentalize relationships in order to maximize financial wealth. In more recent history, the science of economics in countries like Italy initially focused on public happiness and only later added a link to financial wealth.[69] Research shows that greater happiness comes from having deep and stable relationships than from consuming luxury goods, because the latter form of pleasure is fleeting and insatiable.[70]

And yet, close friendships are rare not only in the workplace but may be becoming less frequent in social life in general.[71] This leads to loneliness and social ill-being.[72] Instrumental relationships are no substitute; someone can be lonely even if they are never alone thanks to many instrumental relationships. Non-instrumental relationships, however, reduce loneliness.[73]

The importance of nurturing meaningful relationships is confirmed by a growing body of evidence suggesting that de-commodifying relationships and prioritizing people over purely transactional considerations can yield significant benefits for both individuals and organizations. Friendship in the workplace leads to life satisfaction and positive emotions.[74] Non-instrumental friendship is evident when co-workers voluntarily hang out together outside of work hours and do things totally unrelated to work. Non-instrumental relationships grow when you do something for someone else without expecting anything for yourself (i.e., paying it forward), which can also be a hallmark of meaningful work. In contrast, workplaces that promote instrumental relationships and competition among workers may create mental health issues and decrease mutual problem solving.[75] Even when there is not a clear short-term business case for fostering non-instrumental relationships, the long-term benefits in terms of employee well-being, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment can be substantial.[76]

So why does there seem to be a shortage of non-instrumental relationships? Is it because clever advertisers have convinced us that happiness and meaning can be achieved via financial and material success? If money can buy happiness, then there should not be a qualitative difference in the happiness that comes from, say, going on a date with a friend (non-instrumental) versus with a paid escort (instrumental). Have social media and the digitization of our world contributed to the loss of social skills to form meaningful face-to-face relationships (e.g., the more people use Facebook, the more their mental health deteriorates[77])? There is some irony in observing that at a time in history when we meet more people than ever before, we rely on impersonal dating apps to introduce us to potential long-term meaningful relationships.

Perhaps we shy away from non-instrumental relationships because we have been socialized to avoid non-transactional relationships. When we enter into an instrumental relationship, it is like making a financial investment: we give up something in order to get something in return. And in order to win, we are told to minimize what we give and maximize what we get. This results in a Banker’s Paradox: banks prefer to loan money to people who present minimal risk, and thus people who are the neediest often cannot get a loan.[78] Similarly, transactional thinking tells us to invest our time and energy in developing friendships with well-connected people who have the most instrumental benefits to offer us, and thus we are prone to neglect individuals with the greatest need and who are least able to offer something in return in the future. This is illustrated by the mantra of conventional human resource management: hire the best and the brightest (see Chapter 12). However, as ancient wisdom traditions tell us, relationships with people who may have nothing of instrumental value to offer you create inherent value and joy.[79] Moreover, such relationships improve your ability to nurture non-instrumental relationships with everyone. Befriending those with low instrumental value enables you to relate to the whole community in a way that only relating to people with a similar socio-economic background simply cannot. It opens a window to experiencing altruistic mutual benefaction.[80]

Different ways of encouraging the development of non-instrumental relationships and skills in the workplace are being developed. For example, up to 20 percent of businesses pay workers to do volunteer work, often with chronically underemployed or socio-economically challenged people (e.g., Montreal’s Tomasso Corporation, and the U.S. Bank employees who work in soup kitchens).[81] In some business schools, students are asked to engage in service learning projects or are given practicum assignments where they work with people who are chronically unemployed.[82] Boldr illustrates how promoting authentic relationships can be built into an organization’s vision and policies and practices, and how relationship building can extend beyond immediate colleagues to include clients, community partners, and even competitors.

5.3.1. The FBL Approach to Meaningful Relationships

FBL management places a strong emphasis on developing instrumental relationships and ensuring that they are managed in ways that optimize productivity and financial well-being. When non-instrumental relationships are referred to, the connotation is often negative (e.g., as wasting company time). This negative bias toward non-instrumental relationships is not surprising, given that historically, FBL management offered an antidote to the problems of nepotism and cronyism (i.e., giving jobs to family members or friends without regard for their qualifications).

5.3.2. The TBL Approach to Meaningful Relationships

For TBL management, non-instrumental relationships can be positive if they enhance workplace motivation and productivity, such as when an intra-organizational sports league provides friendly competition among team members. Similarly, leaders are encouraged to develop social skills such as emotional intelligence competencies to empathize with others, managing one’s own emotions in order to improve communication, and establishing trusting and mutually satisfying relationships, because such skills are associated with financial benefits.[83]

TBL management’s embrace of work-life balance may be the best example of its recognition of the importance of non-instrumental relationships to enhance an organization’s financial well-being.[84] However, note that under the TBL approach, work-life balance is less about creating non-instrumental relationships at work per se and more about recognizing the importance of non-instrumental relationships outside of work.[85] Moreover, work-life balance is justified in TBL management because it is seen as creating a more motivated, loyal, and productive workforce, which in turn enhances financial well-being.

5.3.3. The SET Approach to Meaningful Relationships

A SET management approach considers life too short to spend most of it in workplaces where non-instrumental relationships are considered inefficient or a poor use of time. SET management refuses to treat workplace relationships as mere instrumental exchanges between workers, suppliers, and customers, and economic relationships are not seen as impersonal or anonymous commodities but rather as instances of mutual assistance. This means rethinking categories like goods and services by looking at what makes them truly good and genuinely acts of service. SET management seeks to re-personalize and de-commodify goods and services, to embrace how they are making the world a better place; what are conventionally viewed as instrumental relationships are (re)infused with non-instrumental meaning. So, for example, a SET financial services firm does not sell as much product as possible in order to maximize its own profits but rather seeks to live up to its name and truly serve the needs of its customers. In SET organizations, co-workers become friends whom you look forward to spending the day with as you work alongside them to serve customers. Co-workers are much more than “human resources” that you negotiate with to get instrumental work accomplished. Even suppliers and competitors can become friends. Consider the following example from the CEO of a successful SET medical supply company in Brazil:

Many businesses have tried to copy our [beyond instrumental] way of working. Our competitors are shocked by the fact that we are happy to show them how we work—and they try to do the same. They don’t manage to copy our way of working, however, because it is not a formula that says, “do this” “do that” . . . it is a way of being, a way of acting.

Last year there was a competitor who tried to attack us on every corner . . . creating a very difficult situation for our business. At a certain point, the law in Brazil changed and it was a very important change. In order to help this other business, we faxed the news to them. The business owner was so struck by our gesture that he not only wanted to reestablish his friendship with us, but he offered to help us in areas that we find difficult. It was through him that we had the idea of getting in a consultancy—the best decision that we ever made. That consultant was so impressed by how we run our business that he goes out of his way to help us in whatever way he can. This all started through responding to the aggression of our competitors with a different attitude.[86]

Perhaps most importantly, SET management reintroduces values of compassion and altruism into management, which a growing body of research suggests are an inherent part of human nature.[87] Compassion means standing alongside people who are suffering and doing what you can to support them. In management terms, it means creating organizational structures and systems that address the needs of people who are disadvantaged, perhaps especially people who may not have much in the way of instrumental resources to offer in return.[88] SET management’s emphasis on compassion is consistent with people’s values, but often inconsistent with their socially constructed expectations of management. For example, freshman students at Harvard University consistently ranked compassion near the top of their personal values (and power and wealth near the bottom) but ranked compassion near the bottom of what they thought Harvard stood for (and ranked success at the top).[89] What happens when managers are asked to park their compassion at the door?

A discipline of gratitude can help people to become more content with having enough (not always needing more), which in turn is an important step in ensuring that others have enough and promoting prosocial relationships in the workplace. Managers who set up organizational structures and systems that model and encourage members to express gratefulness (e.g., managers who write notes of appreciation may heighten the likelihood of co-workers expressing thanks to others) will in turn foster values consistent with persistent gratitude (e.g., humility, benevolence), which will in turn foster collective gratitude at an organizational level (e.g., corporate social responsibility).[90] Such practices not only enhance individual well-being but also contribute to a more positive and supportive organizational culture, leading to increased job satisfaction and reduced turnover intentions.[91]

Test Your Knowledge

5.4. Peace and Social Justice

The third pillar of social well-being is related to peace and social justice. This includes addressing issues like bullying in the workplace, unsafe working conditions, conflict within and between organizations, and so on.[92] Unfortunately, many people live in communities and countries where their personal safety is in jeopardy. This may be because they live in the “wrong” part of town—for example, where there are violent gangs and racism—or because they live in the “wrong” part of the world. In 2024, for example, fifty countries were ranked as having extreme, high, or turbulent levels of conflict,[93] with about 120 million people having been forcibly displaced.[94]

A lot of resources are spent keeping the world secure. In 2024, worldwide military spending totaled $2.4 trillion,[95] with about another $1 trillion in policing,[96] plus perhaps another $7 trillion in related costs (e.g., taking care of veterans),[97] in sum costing well over $10 trillion a year. This amounts to at least $1,200 for every person on the planet, and about 10 percent of global world product.[98]

5.4.1. Types and Sources of War and Peace

There are two basic ways to understand peace: (1) as the presence of freedom and harmony; and (2) as the absence of war and conflict. The first understanding is consistent with ancient ideas like shalom and shanti, which envision an existence where everyone has enough, and there is mutual understanding and respect within and among communities. Part of the reason that this vision has failed is because humankind has developed an insatiable appetite for more. Again, this is different from how things were for the 100,000 years of human history prior to the agricultural revolution and the advent of money, when people harvested as much food as they needed (not more) and traveled light. By today’s standards, it was a largely egalitarian existence.[99] Perhaps the time has come to reconsider how we think about the purpose of business and put peace building at the center.[100]

According to the second way of understanding peace—as the absence of war— international peace goes hand in hand with the presence of superpowers. For example, during the time of the Roman Empire, the world enjoyed the Pax Romana (Roman peace): there was much less conflict among states within the empire than before, mainly because everyone came under the rule of the empire, which established institutions of social justice. Of course, the nature of that social justice was based on terms and understandings created by the Roman elite and that served their interests. Thus, subjugated peoples often experienced the Pax Romana as a time of being oppressed by the Romans.[101] Arguably, a similar kind of peace also occurred during the period of colonialism, as illustrated by the British Empire and the territories it governed. And today it may be evident in post-colonial empires, where colonialism and the slave trade are gone but have been replaced by economic powers that often perpetuate income inequality similar to that associated with colonialism.[102] Unfortunately, the stable socio-economic structures and systems that widen income inequality also reduce the world’s overall quality of life and have led to conflict.[103]

Perhaps the most important economic factor that has contributed to wars throughout history is related to the human and other energy needed to create society’s goods and services. The relative egalitarianism characterizing the hunting and gathering era changed starting about 12,000 years ago, as humankind learned to tame nature via the agricultural revolution. While there had been variations in social status and power within clans during the hunting and gathering era, the growth of settlements made possible by the agricultural revolution led to greater development of hierarchical structures. Instead of small clans of forty or several hundred members, the leaders of settlements might oversee thousands of people, and leaders of regions tens of thousands. The workers near the bottom of these social hierarchies—often slaves—provided the human energy that enabled settlements and civilizations to prosper. The desire for more workers and more land prompted many wars. In the 3,400 years since the advent of money, the world has been entirely at peace for only 268 years, or about 8 percent of recorded history.[104]

As late as 1795, only 4 percent of the population—33 million people of the global population of 775 million—could be considered in a modern sense to be “free.”[105] The demand for human slaves changed when humankind started to access fossil fuels to power machinery (in the Industrial Revolution; see Chapter 2). Thanks in large part to the energy provided by fossil fuels, today a much greater portion of the world is free from slave-like working conditions, though as of 2022, half the world was living on less than $7.00 per day.[106] However, just as in the past, when wars were fought in order to acquire more land and more worker energy, today wars are often fought in order to ensure access to oil.[107] Since 1973, between 25% and 50 percent of all wars between nation states have been linked to oil.[108]

5.4.2. The FBL Approach to Peace and Social Justice

There is general agreement that international trade facilitates peace among nations. When two countries trade with each other, they become dependent on each other for goods and services, and for jobs related to creating goods and services.[109] As we noted in Chapter 3, FBL management has promoted financial institutions and the establishment of stable international economic relations. Many of these institutions were set up in the wake of World War II to safeguard the economic prosperity of the victors while enabling the economic development of war-torn and low-income countries. While these policies may have been effective in reducing subsequent wars, they were not as effective as hoped for in enhancing the socio-economic development of low-income countries.[110]

Some of the shortcomings may be attributable to the particular ethnocentric orientation associated with FBL management. An ethnocentric orientation is evident when managers enter a foreign country with the belief that practices from their home country offer the best way to manage in a foreign country. Such an approach may be especially likely when managers believe that their home country is more advanced or developed than the country they are working in. While each approach to management (FBL, TBL, and SET) can be seen to have elements of an ethnocentric orientation, the form associated with FBL management is particularly interested in doing business in countries whose infrastructure is well-suited to enhance the financial goals of the firm and does not have a primary focus on improving social well-being.[111]

This sort of instrumentally minded ethnocentrism has contributed to major cultural misunderstandings in history and to ongoing social problems that continue to the present day. This is illustrated by what has happened to Indigenous peoples around the world when their land was settled by foreigners. For example, when Europeans first arrived in North America, their understanding of land ownership was dramatically different than the ideas and values of the Indigenous Ojibway people they encountered. For Ojibway, land is something that people can use, and something that they are stewards over for future generations. When the Europeans asked to make trades for property and land treaties, Ojibway saw this as a request to share the use of the land. They did not see this as giving up their ownership of the land because in their culture, that sort of ownership never existed in the first place. For them it would be presumptuous to think that a person could own a piece of land, because land was sacred and defied ownership (just like you could not “own” a god).[112]

Today, the dangers of an ethnocentric approach based on FBL management are especially apparent when managers from high-income countries use their economic power to implement practices in other countries without respecting or taking into account local socio-cultural considerations. This is perhaps most evident in the global mining industry.[113]

5.4.3. The TBL Approach to Peace and Social Justice

TBL management builds on and elaborates the FBL approach by setting up institutions that seek to improve financial well-being by attending to issues related to social well-being. For example, TBL management supports the United Nations Global Compact, which seeks to facilitate peace by calling on businesses to support human rights laws, eliminate forced or compulsory labor, abolish child labor, eliminate discrimination in the workplace, and work against all forms of corruption. The Global Compact has in turn become a founding member of institutions like the Principles of Responsible Investment and the Sustainable Stock Exchanges.

Like FBL management, TBL management also exhibits its own variation of ethnocentrism, in a form that explicitly recognizes the merit of attending to views of other stakeholders. This is sometimes called a polycentric orientation. Polycentrism is evident when managers enter another country recognizing that the best way to manage involves attending to and adapting practices and customs from the host country. Managers with a polycentric orientation believe that the best way to maximize their firm’s profits is to adapt to and exploit practices and customs evident in the countries in which they are working.[114]

5.4.4. The SET Approach to Peace and Social Justice

SET management believes that businesses should take a proactive role in developing social justice and peace, and in fostering community. This is consistent with the Caux Round Table (CRT) and its case for moral capitalism:

Persons survive when their material needs are met; persons thrive when they are given opportunity to live in the full spirit of their inherent human dignity. Such integration of worldly goods and spiritual aspirations is the foundation for human well-being and happiness. To achieve this fundamentally beneficial and requisite integration, we need a moral community in which to live which provides scope and vision for our aspirations and talents. [115]

The CRT goes on to observe that “neither the law nor market forces are sufficient to ensure positive and productive—in every sense of the term—conduct.” [116] In other words, as SET management practices, businesses need to go beyond merely obeying the law to actually creating positive social externalities, even if doing so does not maximize profits. This is evident in the CRT’s stakeholder management guidelines, which include paying employees a living wage and treating customers with dignity and respect:

Businesses must promote socially and environmentally responsible behavior with all parties.

Businesses affect public policy and human rights in which they operate. They must do what they can to promote human rights, work with initiatives designed to promote community improvement and sustainable development and support social diversity. [117]

Again, like FBL and TBL management, the SET approach can also be seen to exhibit its own variation of ethnocentrism, but in a form that explicitly recognizes the merit of mutual learning from stakeholders, which can be called egalicentrism.[118] Egalicentrism is characterized by two-way, give-and-take communication that fosters mutual understanding and community. SET management does not try to impose a “one size fits all” management style in foreign countries (ethnocentrism), nor does it simply accept that “local managers know best” (polycentrism). Rather, SET management recognizes that international management works best when people from different cultures interact with and learn from one another, resulting in knowledge and practices that neither could imagine on their own.[119] Egalicentrism is not so much picking and choosing the “best of” practices from different cultures as it is developing new approaches by working alongside people who are different.

Coffee for Peace is an organization that exemplifies this approach through its daily operations.[120] It was co-founded in 2008 by current CEO Felicitas “Joji” Pantoja in a low-income region of Philippines, where her job had been to help reduce conflict among different groups living there. Its origins go back to 2006, when Pantoja was mediating a conflict over a land dispute between two parties and noticed that the dialogue improved over a cup of coffee.[121] This observation, coupled with Pantoja’s belief that economic security and stability were key to sustaining social well-being and peace, emboldened her to start Coffee for Peace, which uses coffee farming as a tool for peacebuilding and economic development in conflict-affected areas. The enterprise intentionally creates opportunities for Muslims, Christians, and tribal communities to engage in constructive dialogue while working side-by-side in sustainable coffee production, processing, and consumption. For example, its “Peace Hut” in Mindanao allows military and rebel groups to meet without weapons and engage in dialogue over coffee[122].

By working directly with farming communities and eliminating middlemen, Coffee for Peace ensures farmers receive fair compensation for their crops. The enterprise provides extensive training in sustainable farming practices while using coffee as a tool for facilitating dialogue between conflicting groups. This integrated approach has led to measurable impacts: improved livelihoods for farming communities, enhanced environmental stewardship, and the creation of neutral spaces for constructive conversations between groups with a history of conflict.[123]

The organization’s impact extends beyond peacebuilding: it has helped farmers increase their income dramatically from 30 to 50 pesos to 250 pesos per kilo of coffee beans, while training over 600 farmers—40 percent of whom are women—across thirteen tribal communities.[124] The organization allocates 25 percent of its annual net profits to support peacebuilding initiatives in Indigenous communities. Through this comprehensive approach combining economic empowerment, cultural preservation, and conflict resolution, Coffee for Peace has created a sustainable model where coffee cultivation becomes a pathway to both prosperity and peace.[125]

Test Your Knowledge

5.5. Entrepreneurial Implications

This chapter on social well-being and the two preceding it on financial and ecological well-being describe three different kinds of well-being that entrepreneurs can consider when thinking about the purpose of their entrepreneurship. The criteria entrepreneurs use to define effectiveness and success have powerful implications for the results that they produce. It is therefore essential that entrepreneurs clearly understand their reasons for starting an organization. Why do they want to do it? How will they know if it is successful?

As we noted in Chapter 1, outcomes like revenue, profit, and market share typically come to mind as reasons for starting a business. But these factors are not the primary motivations for most entrepreneurs. Instead, the two most frequently mentioned reasons are (1) to gain greater freedom and autonomy and/or more interesting work; and (2) to address social and ecological problems in the world. The first reason focuses on providing meaningful work for the entrepreneur,[126] and the second is related to addressing ethical issues related to ecological and social peace and justice.

5.5.1. Personal Well-Being for Entrepreneurs

To better understand how entrepreneurship enhances social well-being from the entrepreneur’s perspective, consider research that shows people usually adopt one of three different orientations toward their work.[127] People with a job orientation focus on financial rewards rather than achievement or pleasure; their work is not an important part of their lives but is used primarily as a way to earn money for other things that they enjoy. If you know someone who describes themselves as “working to live” and who cannot wait to get away from the office to pursue their true passion, that person likely has a job orientation.

In contrast, people with a career orientation focus on advancement; their work is an important part of their lives and their work-related achievements help to define their identity as individuals. If you know someone who is committed to being the best at what they do, who networks constantly and pursues opportunities for promotion, that person probably has a career orientation.

People with a calling orientation focus on the effects of their work; they view their work as a meaningful contribution to the world and it is often the most important thing in their life. If you know someone who feels they were born to do a particular task, that it is their mission in life and it seems to consume most of their time and thinking, that person may have a calling orientation.[128] This calling orientation is powerfully illustrated by entrepreneurs like David Sudolsky of Boldr and Joji Pantoja of Coffee for Peace. The calling orientation was the most common (40 percent) among North American mid-career employees (job orientation was 32 percent, career orientation 28 percent).[129]

The orientation that entrepreneurs have toward their work—job, career, or calling—will likely influence their choice of management approach. Entrepreneurs who have a job or career orientation may be more likely to adopt an FBL or TBL management style, given their concerns with maximizing profit, competition, and professional status. In contrast, entrepreneurs with a calling orientation, with its focus on meaningful work and contribution, may be best served by a SET management approach.[130]

Being aware of their work orientation can help entrepreneurs in their planning, and especially in selecting start-up opportunities that will enhance their personal social well-being. Since it is a lot of work to successfully launch and manage a new organization, entrepreneurs may benefit from pursuing opportunities that suit their orientations. If a person becomes an entrepreneur to get rich (job orientation), they will experience greater personal and social well-being in different ventures than those chosen by someone who starts an organization in order to win awards and gain recognition (career orientation) or to change the world (calling orientation). Therefore, when evaluating potential start-up opportunities, entrepreneurs should consider their own work orientation, using it as one of the factors that influence their choices. In particular, if you feel a sense of calling toward an activity, it is well worth exploring that option, because people who view their work as a calling tend to have greater commitment, work persistence, and job satisfaction.[131] Moreover, pursuing a calling rather than a job or career has the additional advantage of potentially benefiting other stakeholders at the same time that it benefits the entrepreneur, since callings tend to be holistically focused.[132]

5.5.2. Ethical Aspects of Entrepreneurship

The second most frequently mentioned motivation for becoming an entrepreneur is to solve problems or make the world a better place. This relatively holistic motivation recognizes that entrepreneurship does not just affect the entrepreneur, it also affects the world. Because entrepreneurship affects others, it is an ethical activity, and entrepreneurs always face potential ethical dilemmas.[133] Ethics are the principles one uses to choose the right action, particularly when the action affects others, and dilemmas are situations in which one must choose when there is no obvious best choice.[134]

Both the entrepreneurial opportunity that is pursued and how it is pursued have important implications not only for the entrepreneur but for all of the stakeholders who do—and do not—benefit as a result. Recall also that whether or not something is ethical depends on the moral point of view being applied (Chapter 1). Consider this question: Was Sudolsky’s decision to pay living wages to his employees globally and to invest 1 percent of quarterly revenue into community development unethical from an FBL consequential utilitarian moral point of view, where maximizing financial well-being is the primary arbiter of right and wrong? Would paying the going rate, instead of a living wage, be unethical from a SET virtue ethics perspective?

Consider also the actions of Boldr and Coffee for Peace in terms of the meaning of life dimensions depicted in Figure 5.1. Along the horizontal dimension, both companies’ decisions could be seen as more holistic than individualistic. Their holistic emphasis is evident in Boldr’s commitment to ensuring the greater good (including opening operations in poor regions and paying a living wage), and Coffee for Peace’s efforts to provide an opportunity for members of conflicting parties to work together for the common good of their community.

In terms of the vertical dimension of Figure 5.1, Boldr’s and Coffee for Peace’s actions can be interpreted as more transcendent than materialistic. While both have a grounding in materialism—ensuring fair compensation and economic empowerment—neither is primarily focused on maximizing individual financial gains. Rather, both organizations seek to create transformative change: Boldr by fostering authentic relationships and meaningful employment across cultures; and Coffee for Peace by using coffee as a tool for dialogue and peacebuilding, and by caring for the natural environment.

In sum, whether they realize it or not, entrepreneurs are shaping the world—affecting stakeholders’ financial, ecological, and social well-being—when they create and manage their organizations. The things that organizations do, and do not do, reflect the ethics of the entrepreneurs who create them. It is therefore crucial that entrepreneurs think about their ethical assumptions and their motivations when creating their organization.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- What someone considers to be meaningful work is related to how they think about a meaningful life, including whether they think the source of meaning is materialistic or transcendent, and whether the focus is individualistic or holistic:

- FBL management tends to have a materialistic/individualistic understanding of meaningful work, which it seeks to fulfill via financial pay and getting ahead.

- TBL management tends to have either a transcendent/individualistic or a materialistic/holistic understanding of meaningful work, which it seeks to fulfill via job crafting and emphasizing the prosocial aspects of a job.

- SET management tends to have a transcendent/holistic understanding of meaningful work, which it seeks to fulfill via encouraging generosity and voluntary simplicity.

- When it comes to nurturing meaningful relationships for organizational members:

- FBL management promotes instrumental relationships that enable people to maximize financial well-being and get ahead.

- TBL management promotes work-life balance.

- SET management promotes putting the person back into what have become instrumental relationships, showing compassion and gratitude in the workplace, and recognizing the importance of non-instrumental relationships.

- When it comes to ensuring peace and social justice for everyone:

- FBL management emphasizes initiatives that promote international trade and practices that support financial well-being; it tends to have an ethnocentric orientation that focuses on self-interests and financial well-being.

- TBL management emphasizes initiatives consistent with the UN Global Compact; it tends to seek optimal financial well-being by attending to others, or polycentricism.

- SET management emphasizes initiatives consistent with the Caux Round Table for Moral Capitalism and fair trade; it tends to have an orientation based on mutual understanding among all stakeholders, or egalicentrism.

- Entrepreneurs’ orientation to their work—be it a job, a career, or a calling orientation—will influence the social well-being associated with their organizations.

- Because it influences the well-being of both entrepreneurs and stakeholders, all entrepreneurial activity has ethical implications, and entrepreneurs would do well to think deeply about the ethics they aspire to.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Should management courses engage students in thinking about the meaning of life? Or is that better left to courses in philosophy? What are the default assumptions about the meaning of life likely to be in a business school if the issue is not openly discussed?

- Ask three people you know if they think their job is meaningful. How do they define meaningfulness? Then ask them how well their work satisfies each of the three criteria for meaningful work that are discussed in this chapter. What have you learned from your friends as they talk about their experiences at work?

- How important is it to you that you find meaningful work in your career? How important is it to ensure that when you become a manager, the people who report to you find their jobs to be meaningful? Would you prefer a job that is meaningful to you and pays $50,000 a year, or a job that is boring and pays $130,000 a year?

- Do you think it is realistic for a manager to permit employees (or even encourage them) to invest time in developing non-instrumental relationships at work? Is there a business case for doing so (e.g., reducing turnover, improving productivity, attracting millennials)? What if there isn’t a business case? Is de-commodifying relationships with suppliers and customers the right thing to do, even if this compromises the ability for an organization to maximize its financial well-being?

- How important is it for businesses to nurture peace and security as a positive social externality? When is this best left to the government, or to the military? How big of a role do you think economic factors play in war? How important is energy?

- How might businesses act as “everyday peace actors” through their routine operations and not just through extraordinary peacebuilding initiatives? Can you think of examples where a company’s everyday decisions might have unintended consequences for peace or conflict in their community?

- This chapter describes many different ways to think about the meaning of life and social well-being. What entrepreneurial opportunities do you see in those ideas? What is a problem you might be able to solve? A solution you could offer? Think of at least five ways an entrepreneur might create value in terms of social well-being.

- This chapter’s opening case is based on the following sources: Anon. (2024, September 18). Global outsourcing leader Boldr: Impact report demonstrates payoffs of ethical outsourcing. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-outsourcing-leader-boldr-impact-report-demonstrates-payoffs-of-ethical-outsourcing-302251417.html; Boldr. (2022). Certified B Corporation profile. B Lab Global. https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/find-a-b-corp/company/boldr; Boldr. (2023a). Our impact. https://boldrimpact.com/impact; Boldr. (2023b). 2023 Impact report. https://boldrimpact.com/impact-report; Boldr. (2024). Boldr economics and our theory of change [Video]. Viewed December 16, 2024, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDeDmsi9B2o&t=15s&ab_channel=BoldrImpact; Martin, L. (Host). (2023). Building a mission-driven BPO: The story of Boldr Impact. (Interview with David Sudolsky). The future workforce [Podcast]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yRQJK53iUA&ab_channel=TimeDoctor ↵

- Boldr (2023b). ↵

- Martin (2023), at 13:00. ↵

- Boldr (2023b). ↵

- Note that some of the language used in the podcast may not be appropriate for all listeners. ↵

- These three dimensions build on three human needs that have featured prominently in the literature: growth (meaningful work), relatedness (meaningful relationships), and existence (secure access to basic essentials like food and shelter). Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4(2): 142–175. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/0030-5073(69)90004-X ↵

- This framework adapts and builds on several reviews of the literature, including Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30(5): 91–127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001; Michaelson, C., Pratt, M. G., Grant, A. M., & Dunn, C. P. (2014). Meaningful work: Connecting business ethics and organization studies. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1): 77–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1675-5. It also overlaps with the threefold understanding of well-being consisting of psychological well-being (e.g., meaningful work), social well-being (friendships), and physical well-being (related to physiological health) identified in Grant, A., Christianson, M., & Price, R. (2007). Happiness, health, or relationships: Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Academy of Management Executive, 21(3): 51–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2007.26421238 ↵

- For example, see Needleman, J. (1991). Money and the meaning of life. Doubleday. ↵

- Rosso et al. (2010). ↵

- Dyck, B. (2015). Spirituality, virtue, and management: Theory and evidence. In Sison, A. J. G. (Ed.), Handbook of virtue ethics in business and management (International Handbooks in Business Ethics series). Springer-Verlag. ↵

- For these data and more like them, see Astin, A. W., Astin, H. S., Lindholm, J. A., Bryant, A. N., Szelényi, K., & Calderone, S. (2005). The spiritual life of college students: A national study of college students’ search for meaning and purpose. UCLA Higher Education Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA; Astin, A. W., Astin, H., Lindholm, J. A., Bryant, A., Calderone, S., & Szelényi, K. (2006). Spirituality and the professoriate: A national study of faculty beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Spirituality in Higher Education, 33(2): 64-90. See also Kim, Y. K., Carter, J. L., Rennick, L. A., & Fisher, D. (2023). The relationship between spiritual/religious engagement and affective college outcomes: An analysis by academic disciplines. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 12(2): 243–265. https://www.ojed.org/jise/article/view/5530 ↵

- Leung, C. H., & Pong, H. K. (2021). Cross-sectional study of the relationship between the spiritual wellbeing and psychological health among university students. PLOS One, 16(4): e0249702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249702 ↵

- Michaelson et al. (2014). ↵

- Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive development approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 347–380). Rand McNally. ↵

- The following data and specific countries listed are drawn from research by Geert Hofstede, which remains among the most cited studies of cross-cultural differences for management. It is based on data collected between 1967 and 1973 from over 100,000 IBM employees working in sixty countries. Hofstede originally identified five dimensions of national culture: (1) individualism, (2) materialism, (3) time orientation, (4) deference to authority, and (5) uncertainty avoidance. In Figure 5.2, Hofstede’s individualism scores were used to categorize countries along the individualistic vs. holistic continuum: holistic countries are ones where Hofstede’s individualism score was from 6 through 26 (number of countries = 18); medium scores were from 27 through 60 (N = 18); and individualistic country scores were from 63 through 91 (N = 17). Hofstede’s materialism scores were used to categorize countries along the materialistic vs. transcendent continuum: transcendent countries were ones where Hofstede’s materialism score was from 5 through 43 (N = 17); medium scores were from 44 through 58 (N = 18); and materialistic country scores were from 61 through 95 (N = 18).For more information about these dimensions and data, see Hofstede’s academic website, at http://www.geert-hofstede.com/; and Hofstede, G. (2003). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage. See also Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.Note that some of Hofstede’s five dimensions have been relabeled. For example, what we call “materialism,” others have identified as quantity vs. quality of life (Robbins, S. P., & Coulter, M. [2003]. Management [7th ed.]. Prentice-Hall); achievement vs. nurturing orientation (Jones, G. R., & George, J. M. [2003]. Contemporary management [3rd ed.]. McGraw-Hill Irwin); aggressive vs. passive goal behavior: (Griffin, R. W. [2002]. Management [7th ed.]. Houghton Mifflin); and masculinity/femininity (Hofstede’s original label).Even though Hofstede’s research is still widely used, we would expect changes to have taken place since he first collected his data. For example, consider the cultural and economic changes over the past few decades in countries like China and South Korea. Also, keep in mind that just as there tend to be differences between countries, there is also a lot of variation within countries (i.e., not everyone from the same country shares the same cultural values). Of course, there are other international data sets that have been collected since Hofstede assembled his data, including the World Values Survey. See for example Homocianu, D. (2024). Life satisfaction: insights from the World Values Survey. Societies, 14(7): 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070119; and Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., de Luque, M. S., & House, R. J. (2006). In the eyes of the beholder: Cross cultural lessons in leadership from Project GLOBE. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1): 67–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2006.19873410 ↵

- A study of female managers in Costa Rica asked them to choose their preferred style among four types of managers: about 15% chose authoritarian (managers make decisions and expect subordinates to implement them) or persuasive (managers make decisions and explain them to subordinates before implemented) types. About 85 % chose either a consultative (managers consult with subordinates before making decisions) or participative style (managers present issues to subordinates and allow them to make decisions). Osland, J. S., Synder, M. M., & Hunter, L. (1998). A comparative study of managerial styles among female executives in Nicaragua and Costa Rica. International Studies of Management & Organization, 28(2): 54–73. https://www.proquest.com/docview/224065495?sourcetype=Scholarly Journals# ↵

- Valenciano-Salazar, J. A., André, F. J., & Martín–de Castro, G. (2022). Sustainability and firms’ mission in a developing country: The case of voluntary certifications and programs in Costa Rica. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65(11): 2029–2053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2021.1950658 ↵

- Costa Rica’s approach is being copied by other countries. Higgins, M. (2006, January 22). If it worked for Costa Rica . . . New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E02E5DA143FF931A15752C0A9609C8B63&mcubz=0 ↵

- Zbinden, S., & Lee, D. R. (2005). Paying for environmental services: An analysis of participation in Costa Rica’s PSA program. World Development, 33(2): 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.07.012 ↵

- However, the study’s authors point out that it would not be suboptimal in terms of acquisitive economics if greater financial value were given to the “carbon fixing” value of the forests and if Costa Rica’s government would receive compensation for this. Bulte, E. H., Joenje, M., & Jansen, H. G. P. (2000). Is there too much or too little natural forest in the Atlantic Zone of Costa Rica? Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 30(3): 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1139/x99-225 ↵

- Marks, N., Abdallah, S., Simms A., & Thompson, S. (2006). The (un)Happy Planet Index: An index of human well-being and environmental impact. New Economics Foundation. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312602893_The_unHappy_Planet_Index_An_index_of_human_well-being_and_environmental_impact ↵

- According to Data Commons, in 2023 GDP/capita in the United States was $ 81,695.19, and in Costa Rica it was 16,595.37. https://datacommons.org/place/country/USA?utm_medium=explore&mprop=amount&popt=EconomicActivity&cpv=activitySource,GrossDomesticProduction&hl=en; and https://datacommons.org/place/country/CRI?utm_medium=explore&mprop=amount&popt=EconomicActivity&cpv=activitySource,GrossDomesticProduction&hl=en ↵

- See the Global Footprint Network website, where you can find information about any other country and even calculate your own footprint: http://data.footprintnetwork.org/#/ ↵

- For year 2023. Otiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2024, February). Happiness and life satisfaction. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction ↵

- According to Central Intelligence Agency. (2025, February 13). United States. In The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/united-states/; and Central Intelligence Agency. (2025, February 19). Costa Rica. In The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/costa-rica/ ↵