Part 1: Background and Basics

3. Management and Financial Well-Being: Jobs, Goods and Services, and Profits

- Learning Goals

- 3.0. Opening Case: A Credit to Banking

- 3.1. Introduction

- 3.2. Varieties of Capitalism and Economics

- 3.3. Financial Well-Being in High-Income Countries

- 3.4. Financial Well-Being at a Global Level: Free Trade versus Fair Trade

- 3.5. Entrepreneurial Implications

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

This chapter describes different forms of capitalism and economics, and gives an overview of FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to financial well-being, as described in the summary below and on the chapter whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand different varieties of capitalism and economics.

- Identify key turning points in the economic history of humankind.

- Summarize the approach to jobs, goods and services, and profits that FBL, TBL, and SET perspectives take in high-income countries.

- Summarize the approach to jobs, goods and services, and profits that FBL, TBL, and SET perspectives take in a global context.

- Describe potential problems and opportunities that entrepreneurs encounter when they try to enhance financial well-being in terms of jobs, goods and services, and profits.

3.0. Opening Case: A Credit to Banking

What’s important is to step back and ask that question: What is the kind of world we want to live in?[1]

Does it surprise you to learn that the quote above is not from a religious leader or social activist, but a banker? At least since the moneychangers of biblical times, financial professionals have had a reputation for greed, self-interest, and turning others’ misfortunes into economic gains for themselves. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when countless homeowners lost everything while governments bailed out “too-big-to-fail” banks (which were largely responsible for the crisis), would anyone believe that bankers and banks cared about making the world a better place? It’s fair to say there is little love lost on bankers.[2] But the man behind the quote, Brendan Reimer, is a different kind of banker who works for a different kind of bank.

The bank in question is Assiniboine Credit Union (ACU), a member-owned co-operative in Winnipeg, Canada, which was formed in 1943 to meet the credit needs of modest-income individuals who were being turned away by standard banks, and who were otherwise subject to very high interest rates from moneylenders. At the first meeting, the grand sum of CAD$100 was collectively pooled. The first loan, in the amount of $50, went to help a member pay off medical debts. And in the early days, ACU business was conducted around a kitchen table.[3]

From those inauspicious beginnings, ACU has grown into an established, full-service financial institution with more than CAD$6 billion in assets, over 140,000 member-owners, 500-plus employees, and a truly outsized impact in the community.[4] Especially since the early 1990s, ACU has played a central role in many of the region’s community economic development initiatives and is responsible for many long-standing programs.[5] These include financial empowerment services through Supporting Employment and Economic Development (SEED) Winnipeg, job creation programs for struggling individuals through Local Investment Towards Employment (LITE), entrepreneurial support through the Entrepreneurs with Disabilities Program, and the Jubilee Fund for social impact investing.

ACU has provided targeted support for the needs of specific populations such as newcomers to Canada and Indigenous communities, and has been the only regional bank to offer specially designed “Islamic” mortgages for Muslims, whose faith permits borrowing and lending but prohibits the charging of interest.[6] In the post-pandemic period, ACU has supported its members to address such wide-ranging issues as food insecurity, tiny home development, and restoration of Winnipeg’s tree canopy, along with being a major sponsor of the world-famous Winnipeg Folk Festival.[7]

At the core of ACU’s work is a mission to serve the economic well-being of its members and the community, especially the financially insecure and underserved. Its ability to do so is fully dependent on having its own financial house in order, meaning ACU must be profitable. But the meaning of profit within this banking institution does not match that of the industry as a whole. In his role as Strategic Partner, Values-Based Banking, Brendan Reimer describes it this way:

Profit is important to financial strength and to being able to do what we want to do as a business, but profit is not our purpose. Our purpose is making a difference in the lives of our employees, our members, and our communities.[8]

In 2020, ACU became a certified B Corp (or benefit corporation), a designation of the US nonprofit entity B Lab, which certifies firms based on a detailed assessment of social and environmental activities and impacts. In their initial assessment, ACU achieved the sixth-highest score ever in B Lab’s history, and the top score ever for a Canadian company. The credit union was subsequently awarded B Lab’s “Best for the World” recognition, adding to an extensive list of awards and recognitions from industry associations and governments over the years. But like profits, such accolades are taken in stride and not given more weight than they deserve. Kevin Sitka, ACU’s chief executive officer, explains:

We did not spend a lot of time looking at where we ranked nationally or globally. We were pleasantly surprised. But we are a mission-driven organization. It’s something we spend a lot of time and effort on and we’re really busy doing the work that goes along with that. . . . It is who we are and who we have been for so many years. This [B Corp certification] is just helping to bring awareness to that.[9]

https://youtube.com/watch?v=CJhB8KAv2HU%3Fsi%3Dcw-I-wK4W3EzqyP6

For more information about ACU and B Corps, see this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJhB8KAv2HU.

3.1. Introduction

Managers are expected to enhance economic well-being. Of course, there are many different ways to measure exactly what economic well-being means, but these measures usually involve the creation of jobs, goods and services, and financial value (especially profits). In this chapter, we examine these three basic standards of economic performance from the Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) perspectives.

As we do so, it will become apparent that the larger economic structures and systems that managers work in are socially constructed.[10] For example, consider how the meaning of the term “market” has changed over time. Not so long ago it referred to a place in the center of a village where people met to buy and sell goods and services with their neighbors. Today, the term market refers to the impersonal laws of supply and demand that dictate what firms can and cannot do. Of course, because they are socially constructed, ideas like the “market” and its “laws” can be and have been revised throughout history (see Chapter 2).

We begin by describing several varieties of capitalism and economics, and we provide a brief history of economic activity. Learning about different types of capitalism—akin to learning about different approaches to management—can improve one’s critical thinking and awareness of possibilities. The current state of economics, capitalism, and organizational practices reflects historical choices, not inevitable laws. Things we take for granted today could have been different, and they can be different in the future. We all determine what the future looks like. Following the discussion of capitalism and economics, we describe FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to the creation and management of jobs, goods and services, and profits in high-income countries as well as from a global perspective. The chapter concludes by considering the implications of our discussion for entrepreneurship.

3.2. Varieties of Capitalism and Economics

The economic context in which managers operate is governed by the political-legal environment, which includes the prevailing philosophy and objectives of the various levels of government, as well as their ongoing laws and regulations. It includes legislation about things like workplace health and safety, consumer protection, pollution, international trade, anti-trust laws, tax rates, minimum wage rates, and many other issues. One chapter is not sufficient to discuss these issues in depth, but we want to briefly introduce two approaches to capitalism (documentational and relational) and two approaches to economics (acquisitive and sustenance) that provide helpful language for talking about these issues. These approaches are influenced by the different types of political-legal systems that permit and regulate economic activity.

3.2.1. Documentational Versus Relational Capitalism

Recall that capitalism is distinct from other economic systems because of its emphasis on rewarding entrepreneurs for profitably combining resources in ways that create valued goods and services.[11] Capitalism has been praised as one of the key innovations in the history of humankind, and it has facilitated the creation of unprecedented financial wealth. The general idea of capitalism influences all the world’s economies. It is therefore helpful for managers to have a basic understanding of the different varieties of capitalism, and what influence a type of capitalism might have on how management is approached in different organizations.

For the purposes of this book, it is helpful to understand two prominent variations on the basic idea of capitalism. Documentational capitalism—which is prevalent in English-speaking countries like the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia—is characterized by its emphasis on detailed contracts, public financial reports, short-term maximization of financial performance, management independence and rights, stringent anti-trust legislation, rewarding a labor force that is mobile and has transferable skills, and using stock options to motivate managers. In contrast, relational capitalism—which can be found in countries like Japan, Germany, France, Finland, and Italy—is characterized by its emphasis on relational contracts, the long-term reputation and financial performance of an organization, employee rights, satisfying the needs of many different stakeholder groups, and investment in developing the skills of employees.[12]

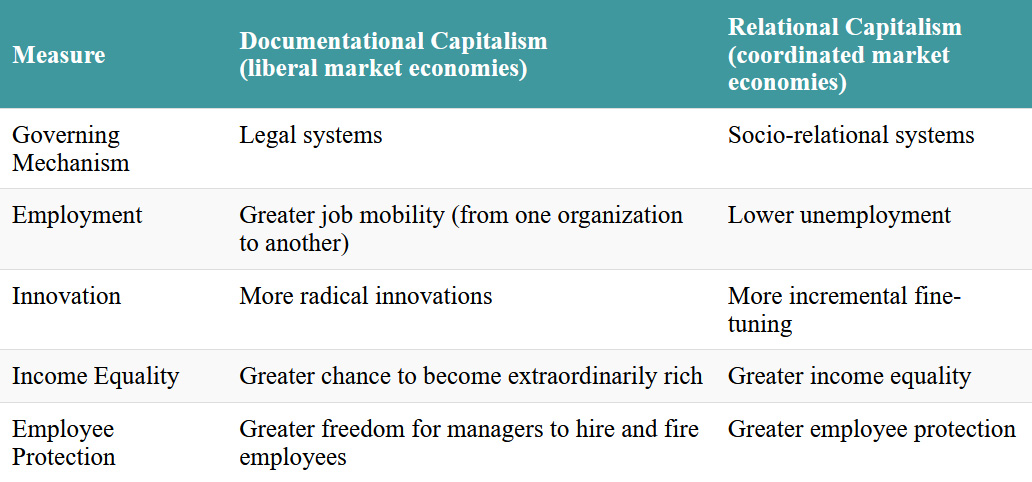

Some key differences between these two types are summarized in Table 3.1.[13] In very general terms, documentational capitalism is more consistent with FBL management, while relational capitalism is more conducive to TBL and SET approaches (where there is more emphasis on building trust and relationships among stakeholders than on solely developing comprehensive legal contracts).[14] Managers in documentational capitalism tend to have more freedom to make top-down decisions and to act quickly, and there are more generous financial rewards for managers who are able to maximize their organization’s profits. Managers in relational capitalism generally look at the longer term. There is more continuity of membership within organizations (less job-hopping from one organization to another), and there is greater emphasis on developing strong interpersonal relationships with managers in other organizations instead of developing formal contracts. The increased importance of relationships creates an incentive to pay more attention to the needs of all stakeholders, which increases the attention paid to socio-ecological issues.

Table 3.1. Some differences between documentational and relational capitalism

3.2.2. Acquisitive Versus Sustenance Economics

Economics refers to how goods and services are produced, distributed, and consumed. There are at least two basic varieties of economics. An FBL understanding of economics points to the importance of the financial marketplace, to the so-called laws of supply and demand, and to the creation of financial wealth. This is similar to an idea that Aristotle developed over 2,000 years ago called acquisitive economics, which refers to the management of property and wealth in such a way that the short-term monetary value for owners is maximized (profit maximization focus).[15] Modern economic theory has refined this basic notion. For example, today the main economic theories that underpin FBL management explicitly add the assumption that not only are all economic entities (individuals and organizations) seeking to improve their financial well-being, they are so strongly motivated to optimize their short-term self-interests that they are prone to lie, steal, cheat, and give out bad information in a calculated effort to mislead or confuse partners in an exchange.[16]

The TBL and SET approaches have a different view of economics. The TBL view, which combines elements of FBL and SET approaches, is called hybrid economics, which refers to managing property and wealth to maximize monetary value for owners, while simultaneously reducing negative socio-ecological externalities for key stakeholders (harm reduction focus). The SET approach can be traced back to Aristotle’s second concept, that of sustenance economics, which refers to managing property and wealth to increase the long-term overall well-being for owners, members, and other stakeholders (well-being focus). Sustenance economics emphasizes real human needs, community-oriented values, long-term multi-generational concerns, and stewardship. It speaks to issues of quality of life that cannot be meaningfully expressed by or reduced to quantifiable measures like financial wealth, income, or goods consumed.[17] Both TBL and SET perspectives agree that dysfunctions occur when managers are solely driven to maximize financial profit without regard to socio-ecological externalities.

Before we examine how managers enhance economic well-being via jobs, goods and services, and profits, it is helpful to consider a brief historical overview of how these three elements came to be important and how they fit together.

3.2.3. Simplified Models of the Economy

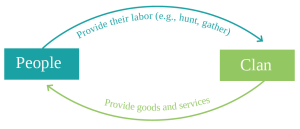

Humankind has always worked in groups in order to create the goods and services that people require to survive and thrive. Before money was invented, the economic model looked like Figure 3.1.[18] People contributed to their clan’s well-being by performing tasks (e.g., hunting, gathering food, caring for children), with everyone in the clan sharing the resulting benefits (e.g., everyone had food, social relationships, and security). The clan was both the producing and the consuming group, with all members actively participating in both aspects, so that producing goods and services was a part of clan membership. Everyone had a personal connection to the goods and services produced in the clan.

Figure 3.1. Simple economy (starting 40,000 BCE)

In terms of jobs, estimates suggest that on average people worked about twenty-four hours a week on hunting and gathering, and about nineteen hours on childcare, cooking, and other domestic tasks.[19] In terms of goods and services, people only had the (fresh) food that was in season, there were no modern healthcare services, and life could be harsh. Because the idea of money had not yet been invented, there were no profits per se.

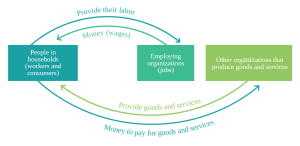

Over time, and with the advent of money around 1500 BCE, the economic situation changed so that eventually there was a separation between the unit of consumption (i.e., the household, where people lived) and the unit of production (the workplace, where people had jobs and worked to produce goods and services). As shown in Figure 3.2, people now “sold” their labor for money (wages), typically working to produce goods and services they would not personally use. Instead, workers used their wages to purchase goods and services from a variety of organizations, most of which they were not members of. Before money, people had used their labor to produce the goods and services they consumed. After money became a generic measure of value, the goods and services that people produced became separated from the goods and services they consumed. Business owners and managers could choose whom to hire (or not hire) and had some motivation to create profits by reducing labor and other input costs, increasing productivity and efficiency, and selling at the highest price the market would tolerate. During this second era, people gained additional freedom and more choice, and there was opportunity for greater financial inequality than there had been in the clan economy.

Figure 3.2. Simple monetized economy

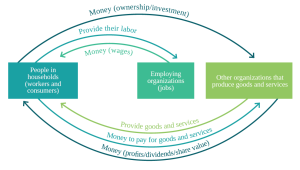

With the advent of corporations (businesses that are distinct legal entities that are separate from their owners, see Chapter 2) during the Industrial Revolution, the situation changed again (see Figure 3.3). As organizations grew in size and breadth, relationships between the household (worker and consumer) and the business (employer, merchant) became even more impersonal. Prior to corporations, even though production and consumption were separated, the economy was based mostly on small local organizations, with owners often living in the same community as their employees and customers. This co-location and face-to-face contact encouraged everyone to treat each other with dignity and not merely as the means to an end.[20] In contrast, the proliferation of corporations led to increasing distance between owners, employees, and customers, thereby eroding face-to-face relationships and putting greater emphasis on quantifiable measures of success. For example, instead of seeing the smile of a satisfied customer or the pride of a worker completing a task, an owner who had no contact with the organization’s operations would only see impersonal reports of sales revenue and employee productivity. Because this was the main information owners had, it grew in importance. As we noted in Chapter 2, the increased emphasis on maximizing the financial well-being of owners contributed to a self-fulfilling assumption that everyone was financially self-interested. As corporations have continued increasing in size and influence—most of the world’s 100 largest economic entities are businesses, not countries—the relative power of owners and managers has increased. This has resulted in financial benefits for people from households who own shares in corporations, including shares owned indirectly through pension funds invested in the stock market.[21]

Figure 3.3. Simple corporate economy

With this simplified understanding of the corporate economy in hand—and the realization that it was socially constructed, not inevitable or “natural”—we can now examine how the FBL, TBL, and SET approaches differ on the three dimensions of economic well-being: jobs, goods and services, and profits. First, we examine each dimension from the perspective that characterizes much of the management literature, namely that of managers working in high-income countries like the United States.[22] Second, we examine each dimension from a more global perspective, aware that most of the world earns less than $3,000 per year.[23]

Test Your Knowledge

3.3. Financial Well-Being in High-Income Countries

3.3.1. Jobs

Jobs—that is, opportunities to get paid by an organization in return for doing work that produces goods and services—are the first dimension of economic well-being. People generally expect managers to create jobs that allow them to meaningfully contribute to society and enable them to earn money so that they can purchase the goods and services they need to have a good life.

The FBL Approach to Jobs

Thanks largely to FBL management, today there are more jobs to choose from than ever before. Supporters of the FBL approach are rightly proud of its job creation record. For example, the number of jobs in the United States increased from about 60 million in 1950 to over 160 million in 2023 (an increase of about 270 percent, similar to the growth in population).[24] People entering the workforce are faced with an unprecedented number of career options and are given an unprecedented number of educational options to prepare for the careers that they would like to pursue. Moreover, people can work for a variety of organizations (e.g., if they are not satisfied with their pay or other work arrangements in one company, they are free to move to a competitor). All these jobs based on FBL management principles were created in order to enhance employers’ financial well-being.

The TBL Approach to Jobs

TBL management considers not only the number and variety of jobs that are available but also the social and ecological implications of those jobs. The widening of income gaps is a particularly relevant example of how jobs can affect financial and social well-being. For an example from the United States, in the fifty years from 1974 to 2024 the average productivity per worker increased by 90 percent, while the average pay increased by only 32 percent.[25] Net productivity refers to the growth in the total goods and services created per the number of hours worked. During about the same time period, CEOs’ pay increased by over 1,000 percent, and in 2023 CEOs were paid about 290 times what the typical worker was paid, compared to seventeen times as much in 1973.[26]

Despite the growth in number of jobs and productivity and pay for top managers, today about 37 million people in the United States—the largest and most productive economy in the world—still live in poverty.[27] In other words, the gap between the rich and the poor has been widening. The TBL approach considers this gap worrisome because it may cause reduced job satisfaction, increased turnover costs, lower productivity, and ultimately reduction of a firm’s financial performance. TBL management seeks to increase job satisfaction and reduce turnover costs, thereby contributing to a firm’s financial bottom line.[28]

The SET Approach to Jobs

The SET approach shares TBL management’s concern about widening income inequality, but not only because of its effect on worker motivation, performance, and contribution to the firm’s financial bottom line. SET management recognizes that income inequality is associated with other negative societal outcomes, including increased levels of anxiety, obesity, crime, homicide, and differences in how genders are treated. Income inequality is also connected to lower levels of mental health, life expectancy, social mobility, and social trust. The greater the income inequality, the lower the overall quality of life (interestingly, a widening inequality gap also worsens the quality of life for the rich).[29]

The SET perspective also questions the focus FBL and TBL approaches place on productivity maximization, an emphasis that has created unintended negative societal externalities. In particular, SET seeks to create jobs for people who may not find a job in productivity-maximizing FBL and TBL firms. For example, organizations like Greyston Bakery in New York (see Chapter 1) and BUILD Inc. in Winnipeg, Canada,[30] deliberately hire people who have been in prison or are from other groups who often find it difficult to get a job. These organizations may hire a person even if they need considerably more training than other candidates who are better qualified, because the goal is to help everyone to earn a living and contribute to society, not merely to maximize productivity (see also Chapter 12).

SET management seeks to ensure that all workers are paid a living wage, which is enough money to pay for the basic amenities of life, including adequate housing, food, clothing, education, and healthcare. A living wage is typically higher than the legal minimum wage, and indeed most of the people who earn a minimum wage do not earn a living wage.[31] Research suggests that when a firm pays a living wage it has a negligible effect on the firm’s financial overall costs, in part because it improves worker morale and productivity while reducing absenteeism and turnover.[32] This is illustrated by companies like Assiniboine Credit Union (opening case) and Enviro-Stewards that pay employees to volunteer on company time, which helps to “attract and retain staff with outstanding technical competence, integrity, judgement, interpersonal skills and a strong desire to serve others.”[33]

Test Your Knowledge

3.3.2. Goods and services

Humankind requires goods and services in order to survive. Our ability to thrive is influenced not only by how the goods and services are created (e.g., jobs), but also by whether there are enough appropriate goods and services available, and whether they are affordable and sustainable.

The FBL Approach to Goods and Services

The general goal of FBL management is to increase the quantity and profitability of goods and services produced, with more being better. For example, it is common to measure economic well-being in terms of growth in gross domestic product (GDP), which measures the total financial value of all the goods and services produced within a country. The FBL approach has proven to be very successful when financial well-being is measured in these terms. In the fifty years prior to 2025, the GDP of the United States grew seventeen-fold (from $1.5 trillion to $27.3 trillion).[34] By this standard, FBL management has been very successful.

The TBL Approach to Goods and Services

TBL management considers not only the financial value of goods and services that are created but also their socio-ecological externalities. For example, the TBL approach promotes the development of alternative sources of energy (e.g., wind, solar) and the reduction of energy usage (e.g., LED lighting, reduced packaging) in order to increase profits and protect the environment. Industries related to alternative sources of energy have grown substantially since 1990, consistent with what is promoted by a TBL approach.

Similarly, consumer packaged goods (CPG) marketed as sustainable are one of the fastest-growing retail segments, growing from a 13.7 percent market share in 2015 to 18.5 percent in 2023 (about 35 percent market share growth over eight years).[35] This category had an estimated value of $293 billion in 2023 and is projected to continue growing at a compounded annual rate of 10.7 percent till 2030, driven by consumers with a clear preference for environmentally and ethically sound products and willing to pay a premium for them.[36] Unfortunately, when managers recognize the increasing demand for sustainable products, they may be tempted to market goods as “sustainable” even if they are not, via a practice called greenwashing—which refers to deliberately using misleading information in order to present a false image of ecological responsibility (see also Chapter 4).

Simultaneously improving ecological well-being and profits can be challenging for TBL firms, as illustrated by the Taiwanese shipping giant Evergreen, a leading example of TBL best practices in the global transportation and distribution of goods. Their extensive sustainability agenda is laid out in a comprehensive, audited annual report, and centers on an ambitious goal of achieving carbon neutrality (aka, net zero) by 2050. Since 2008, Evergreen has made consistent progress toward this goal based on their primary metric of CO2 intensity, which is a measure of how much carbon is produced for a standardized quantity of goods shipped.[37] However, Evergreen also has an ambitious growth strategy and in 2023 alone added thirty-three container ships to their fleet, which contains many of the largest ships in the world.[38] As a result of this growth in size, Evergreen’s reports indicate that the company’s overall carbon emissions continue to rise. Furthermore, Evergreen’s net zero strategy does not take into consideration the carbon footprint associated with the production, use, and disposal of the ever-increasing amount of goods it ships around the world annually.

The SET Approach to Goods and Services

Rather than focus on producing more goods and services, the SET approach recognizes that many of us already consume more goods than the planet can sustain. SET management emphasizes sustenance economics and questions the FBL view that economic growth is always good. From a SET perspective, a first step in building a sustainable economy requires recognizing when enough is enough, and that having more than enough may actually impoverish other aspects of our lives.[39] This view inverts the logic of economists like Henry Wallich who argue that “growth is a substitute for equality of income. So long as there is growth there is hope, and that makes large income differentials tolerable.” If this claim is true, namely that growth and income equality are substitutes for each other, then the SET approach prefers the corollary: “Greater equality of income is a substitute for growth.”[40]

Similar to TBL management, the SET approach seeks to improve organizational performance via innovative technologies that enhance socio-ecological well-being. However, unlike FBL and TBL approaches, SET management actively and deliberately challenges the thinking that more consumption and more sales and more revenue are necessarily better. SET asks questions such as, What if we already have too many goods and services on the market? Do we really need to purchase fifty-eight new garments a year?[41] Do we really need the 50 percent increase in square footage per person in our homes compared to what we had fifty years ago? Do we really need the latest version of an iPhone? Do we really need to own our own car? Can we live better with less?[42]

The SET approach is consistent with research that shows that engaging in voluntary simplicity makes people happier.[43] Rather than working long hours in order to earn money to go to restaurants and have better smart phones, people appreciate having more time to cook home-made meals and to visit with friends in person. From a SET perspective, wanting more than enough goods—and spending the time (and Earth’s resources) to produce and acquire them—is dysfunctional and unethical,[44] especially in a world where many people do not have enough.[45]

3.3.3. Profit

The word “profit” is used here in its most general sense, to indicate that there is a “proper fit” (pro-fit) between the goods and services an organization produces (value creation) and the financial resources it is able to earn as a result (value capture). This is also consistent with Darwin’s understanding of “survival of the fittest,” which focuses on ecological fitness (i.e., the “fit” in relationships with others in a physical system or environment); it does not refer to being fit in the sense of being the most powerful or strongest but instead fitting within an ecosystem’s resource exchange relationships.[46] Such an understanding of pro-fitable organizing can apply to for-profit businesses, but also to nonprofit and government organizations, where it can be associated with providing sustainable goods and services in a way that is financially sustainable. For example, an organization like World Vision is pro-fitable when it has enough funding to pay for the work it does.

The FBL Approach to Profit

The FBL approach seeks to maximize financial profits by increasing the financial value it captures from the goods and services it offers. Consistent with an acquisitive economic perspective, FBL management defines the profit dimension of economic well-being in terms of money made. And the track record of FBL management is impressive in these terms. With few exceptions (e.g., the recession of 2008), corporate profits in the United States have been on an increasingly upward trajectory (e.g., from $73 billion in 1974 to $3,128 billion in 2024, a forty-three-fold increase, which is considerably greater than the seventeen-fold increase in GDP over that same time).[47]

The profitability performance of financial institutions may be an example of the FBL approach at its best. In the United States, the proportion of total GDP generated by the finance and insurance industry grew from 2.8 percent in 1950 to 7.3 percent in 2023. This industry, which accounted for 9 percent of total profits (of all sectors in the US economy) in 1950, reached nearly 40 percent in the early 2000s (prior to the financial crisis) and was sitting at 17 percent in 2023.[48] Bankers have benefited from deregulation and opportunities to lend more money than they have on reserve, thereby literally growing the size of the economy (and in doing so creating value for society) in profitable ways (increasing the banks’ capture of financial value). The pay of jobs in the banking industry is also noteworthy: people working in finance earn 50 percent more money than employees with a similar education working in other parts of the economy.[49]

The TBL Approach to Profit

The TBL approach is also primarily concerned with financial profit, but it proposes different means for achieving it. Many of the studies that show “it pays to be green” suggest that TBL management’s focus on the triple bottom line is more profitable than FBL management’s limited focus on just financial issues.[50] From a TBL perspective, it makes sense that profits would increase for companies that reduce their ecological input costs (e.g., reducing the energy used to light their facilities) and who find cost-effective ways to improve worker motivation and productivity (e.g., offering flextime, casual dress Fridays). Organizations like Walmart and Amazon demonstrate the benefit of TBL thinking.

The SET Approach to Profit

While FBL and TBL supporters are justifiably proud of generating impressive financial profits, the SET perspective questions the unsustainable and insatiable pursuit of material and financial wealth. Instead, the SET approach favors measures of economic performance that consider positive and negative socio-ecological externalities. To illustrate, the developers of the GDP measure never intended for it to be used as a reflection of a nation’s economic well-being.[51] They note, for example, that GDP goes up when someone steals a car because the owner then needs to spend money replacing it. It also goes up when criminals are put in jail (which creates jobs at the prison), or when an oil pipeline bursts (and the pollution needs to be cleaned up). GDP also goes up when toxins in the air create illness and hospital expenses, and when mental stress creates the need for psychiatrists and medication. In short, although GDP is widely interpreted as a measure of national economic well-being, it includes many detrimental activities that are harmful to society.

By contrast, the SET approach suggests measuring economic well-being via something akin to the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), a measure of quality of life that accounts for the following factors:[52]

- Income distribution: GPI increases when people who have a low income receive a larger portion of national income and decreases when their share declines.

- Crime: Unlike GDP, which grows with costs of crime (e.g., because of legal and healthcare costs, property damage), GPI subtracts these costs.

- Resource depletion: Unlike GDP, which ignores externalities like the depletion and degradation of forests, farmland, wetlands, and nonrenewable minerals, GPI treats these as costs.

- Pollution: Unlike GDP, which often double-counts pollution (first for the costs incurred in creating pollution, and second for the costs of cleaning up pollution), GPI subtracts costs of water and air pollution based on their damage to the environment and human health.

- Long-term environmental damage: GPI recognizes the negative financial externalities associated with carbon emissions.

- Leisure time: GPI goes up with increases in leisure time and down with decreases.

While high-income countries achieve impressive increases in GDP, it is not unusual for their GPI to lag behind. For example, one study showed that over a forty-five-year period the United States’ per capital GDP more than doubled, while its GPI decreased by 28 percent.[53]

SET management also makes a distinction between two types of profit: conventional and genuine. Conventional profit refers to the difference between a firm’s financial expenses and its financial revenues, without considering negative socio-ecological externalities (e.g., it does not account for the $5 trillion in negative ecological externalities associated with the world’s 1,200 largest corporations in 2018[54]). Genuine profit refers to the difference between a firm’s financial expenses and its financial revenues after considering its socio-ecological externalities. For example, a firm might voluntarily pay fees in order to address the negative externalities associated with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, as illustrated by companies that voluntarily purchase carbon offsets when employees travel by air. Or a firm may refuse to have its products made in overseas factories that use child labor or have oppressive working conditions.[55] Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company (see Chapter 15) is an example of a bakery that tries to earn genuine profit. It uses local organically grown grains, hires people facing barriers to employment and pays a living wage, uses electric vehicles, and has retrofitted its building to be environmentally friendly.

Test Your Knowledge

3.4. Financial Well-Being at a Global Level: Free Trade versus Fair Trade

Thus far, we have focused our discussion on managing economic well-being within the context of high-income countries. We will now adopt a more global perspective, drawing greater attention to the challenges of economic well-being facing people in low-income countries.

3.4.1. Jobs in a Global Context

The FBL Approach to Jobs

The FBL philosophy for improving the global economy can be summed up with the basic idea of “free trade” and the maxim that “a rising tide raises all boats.” Free trade refers to the idea that goods and services can flow across national and international boundaries without financial barriers (i.e., tariffs, quotas, or subsidies). The assumption underlying the FBL philosophy is that everyone will benefit if we remove trade barriers between countries. When jobs, goods and services, and money can flow freely across borders, the “invisible hand” (see Adam Smith, Chapter 1) will guide them to the most productive locations and uses, so that the output and financial well-being of total global economy will be maximized.[56]

Our highly developed international transportation systems, coupled with the ability to communicate instantly around the world, helps put the FBL vision for the global economy into practice. Factories can be located wherever labor costs are the lowest, and products can be shipped to wherever demand is greatest. Indeed, this globalization—which refers to changes in economics, technology, politics, and culture that result in increasing interdependence and integration among organizations and people around the world—is considered by some to be the genius of the FBL approach, because it creates financial incentives for multinational corporations to create jobs in economically depressed regions of the world. Insofar as businesses are motivated to reduce their financial costs, they will be motivated to locate factories in countries where people are willing to work for a low salary. This should result in jobs moving to places where they are most needed, promising a “win-win-win” proposition: shareholders win because financial labor costs will be reduced; consumers win because the prices of goods can be reduced; and unemployed people in low-income countries win because they get a paying job. Those jobs will also help to grow the economies in low-income countries. As of 2024, 98 percent of garments purchased in the United States were imported,[57] whereas as recently as 1990 only 50 percent were imported.[58] In 2018, the average American purchased sixty-eight new garments a year,[59] about five times more than in 2000,[60] in part because of fast fashion and decreasing costs thanks to jobs moving to low-income countries.

Proponents of FBL management point out that globalization has had a positive effect on the world’s people who have the greatest financial need. For example, the proportion of people in the world living in extreme poverty (i.e., spending less than $2.15 international dollars per day) decreased from 82 percent in 1910 to 60 percent in 1970, 37 percent in 1990, and 8.5 percent in 2024.[61]

The TBL Approach to Jobs

TBL management is interested in not only the number of jobs that are created around the world but also the quality of those jobs. A study by the World Bank that interviewed 20,000 people facing financially insecurity from more than forty countries found that when asked about what they needed, people didn’t talk so much about wanting money per se. What they wanted was a secure job where they could earn enough money to provide their families with food, clothing, shelter, and education.[62] However, because of the relative power advantage that large organizations have over unemployed people in low-income countries, people with little financial security have little negotiating power. Indeed, many of the new jobs that have been created via globalization do not pay a living wage and have terrible working conditions.[63] The TBL management response to such conditions has been the development of third-party accreditation agencies that monitor overseas working conditions. For example, Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production (WRAP) is a nonprofit, independent association of social compliance experts that promotes and certifies humane, ethical, and lawful manufacturing around the world.[64] Improving working conditions offers TBL firms many benefits, including helping them to maintain a positive brand image with consumers. One study found that paying factory workers 20 percent above the industry average and establishing a welfare fund for workers improved profitability.[65] Similarly, other research suggests that firms that care enough for workers and the environment to be listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) can enjoy significant financial gains.[66] The argument that compensating employees well can increase productivity and firm performance goes as far back as Henry Ford (who in 1914 paid workers more than double the rate of neighboring factories), and multiple recent studies support this practice even as firms struggle with the economic aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.[67]

The SET Approach to Jobs

The SET approach seeks to create jobs that meet human needs and treat all people with dignity and respect. Such jobs are lacking in low-income countries, even among well-known FBL and TBL corporations. For example, Apple has faced persistent criticism for having its iPhones assembled in factories with numerous labor-rights violations, including mandatory overtime, bullying, harassment, and conditions that make workers prone to suicide.[68] In contrast, SET management is evident in firms like Taylor Guitars, which implemented training, wage increases, and job-security measures immediately upon purchasing an ebony mill in Cameroon (see opening case, Chapter 1).

The SET approach is reflected in the jobs created by the best practices of fair trade, which tries to ensure that workers in low-income countries are paid a fair price for the products they produce. Fair trade helps consumers to respect producers and provides transparency so that consumers know the working conditions of producers. Fair trade allows consumers in high-income countries to use their purchases to reduce income inequality, while benefiting the environment by providing eco-friendly products.[69] The World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) works toward 10 Principles of Fair Trade, the first being to create opportunities for marginalized producers “to move them from insecurity and poverty to economic self-sufficiency and ownership.”[70] Although they can be challenging to put into practice,[71] key principles of fair trade include paying a fair price (vs. paying the lowest price the market will withstand), implementing gender equity (vs. allowing women to be persistently underpaid), offering healthy working conditions (vs. sweat shops or child labor[72]), fostering mutual respect between producer and consumers, and practicing environmentally friendly practices. The Fairtrade Mark, which first appeared on just three products in the United Kingdom in 1994, now appears on over 37,000 products offered by over 2 million farmers and producers belonging to nearly 2,000 producer organizations from seventy countries. Fair trade products are sold in over 140 countries.[73] An example is the Divine Chocolate Company, which is 33 percent owned by cocoa farmers from Ghana (see Chapter 2).

3.4.2. Goods and Services in a Global Context

The FBL Approach to Goods and Services

FBL management encourages the free movement of goods and service across international borders through minimizing tariffs, quotas, and government subsidies. Tariffs—which are taxes on goods or services entering a country—protect domestic companies from international competitors. Quotas place restrictions on the quantity of specific goods or services that can be imported (or exported). Government subsidies are direct or indirect payments to domestic businesses that help them compete with foreign companies. For example, farmers in high-income countries received about $800 billion dollars in subsidies in 2023 to allow their domestic agricultural products to be price-competitive in global markets.[74]

Free trade is enhanced by general trade agreements. The World Trade Organization (WTO) strives to make it easier for goods to flow among member countries by urging countries to lower tariffs and to work toward free trade and open markets. Created in 1995, the WTO has over 160 member countries that represent 98 percent of global trade. In addition to the WTO, there are a series of regional free trade agreements among different countries. Many of these have been facing considerable opposition, for a variety of reasons (e.g., they are perceived to favor large international corporations rather than smaller locally owned firms, and they restrict the ability of governments to create regulations for their local jurisdictions).

The United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), which took force in July 2020 (superseding the North America Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA], signed in 1994) has eliminated numerous tariff and non-tariff barriers between the United States, Mexico, and Canada. The agreement affects over 510 million consumers, about $30 trillion dollars in annual economic activity, and constitutes one of the largest free trade zones in the world.

The European Union (EU) is a group of almost thirty European countries committed to making trade among members easier by lowering tariffs and other impediments to trade. The EU comprises about 450 million consumers and has a common currency (the euro). In 2020, the United Kingdom withdrew from the EU (“Brexit”) and a new free trade agreement—the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement—was signed. There are various other free trade organizations as well. For example, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) includes ten nations and over 600 million people in one of the fastest-growing economic regions in the world.

Enabled by free trade, global GDP increased from $10 trillion in 1950 to $139 trillion in 2022 (a fourteenfold increase), during which time the global GDP per capita went from $4,000 to over $17,000 (a fourfold increase).[75] Between 2013 and 2023, global GDP has increased 3.0 percent per year, with lower-income countries averaging 3.59 percent per year and high-income economies less than 2 percent. The FBL approach counts this larger growth in lower-income countries as a success and as support for the maxim that “a rising tide raises all boats.”[76]

The TBL Approach to Goods and Services

Like the FBL approach, TBL management supports free trade because firms can become more profitable if they expand their target markets to consumers in foreign countries. In particular, firms that develop low-priced goods and services for people on low incomes will not only empower and welcome them into the globalized economy, but the firm itself will create more revenue and a larger customer base. This is the basic idea behind what is known as the Base of the Pyramid,[77] which has developed alongside TBL theory and refers to the billions of people surviving on extremely limited incomes.[78] For example, in 2007 the UK-based organization Vodafone helped launch an organization called M-PESA to provide financial services to people in Kenya via their mobile phones. The venture has generated healthy profits for the company, which had 57 million customers and $885 billion revenue in 2023.[79] Extensions of Base of the Pyramid theory have been developed to encourage firms from high-income countries to partner with communities in low-income countries in order to co-create mutually beneficial businesses that produce goods and services in low-income countries.

Unlike the FBL approach, TBL management is more attuned to the potential financial benefits that can come from developing goods and services that are not directly valued by the high-income marketplace. For example, from an FBL perspective, research and development should be invested in developing drugs that target the concerns of people in high-income countries (like the top-selling drugs for obesity, sleep disorders, and sexual dysfunction) rather than in developing drugs for people in low-income countries, who can’t afford to purchase them. In contrast, a TBL approach is evident in the actions of pharmaceutical company Merck, which helped to develop a product called Mectizan that can prevent river blindness, a disease prevalent among the poorest people in the world. For over thirty-five years, Merck has supplied Mectizan for free to anyone in the world who needs it and works with organizations such as the World Bank and the World Health Organization to distribute medicine in remote areas. Merck’s managers believe that actions like these ones help to make their firm more attractive to the world’s best scientists, because they know that discoveries at Merck may reach sick people regardless of their economic status.[80]

The SET Approach to Goods and Services

The SET approach also supports international trade agreements but is more interested in fair trade than in free trade. Consistent with the rise of SET management, the fair trade movement is growing in consumer awareness. For example, Fairtrade International products averaged 20 percent annual revenue growth from 2004–2018. Recent surveys indicate that over 70 percent of shoppers recognize the label, that it creates positive brand associations, and that 56 percent are willing to pay more for a Fairtrade product even with cost-of-living increases.[81] This growth seems to represent a great opportunity to bring living wages to impoverished farmers.[82]

Unlike FBL and TBL approaches, SET management has misgivings about conventional international free trade agreements for two reasons. First, free trade benefits the rich more than the poor. While it is true that free trade agreements have been associated with impressive growth in the global economy, it is not clear that this has been a win-win proposition. The disparities between rich and poor have been increasing, and the wealthy have benefited more from globalization than the poor.[83] According to the 2022 World Inequity Report, the “richest 10% of the global population currently takes 52% of global income, whereas the poorest half of the population earns 8.5% of it.”[84] Another study suggests that in terms of the relative economic benefits associated with globalization over the past fifty years within countries, it has had a positive effect on only the richest top 5 percent (with the top 1 percent garnering 24 percent of the benefits). The lowest 70 percent experienced statistically significant losses, while the group in the middle (i.e., the 25 percent between the lowest 70 percent and the top 5 percent) did not experience a statistically significant difference).[85]

Rather than support tariffs, quotas, and subsidies that allow the relatively rich and powerful companies and countries to maintain or gain further economic advantage, SET management is more likely to favor subsidies for low-income countries to develop their economies and for practices that benefit the natural environment. For example, the current $800 billion in agricultural subsidies in high-income countries cause unintended negative externalities for farmers in low-income countries (and for the natural environment; see Chapter 4). These subsidies represent around $1,400 per year for each of the world’s 570 million small-scale farmers, a large portion of whom earn less than that in a year.[86] Indeed, the unwillingness of high-income countries to reduce their barriers (e.g., reduce their tariffs and lower subsidies to their own producers) to agricultural exports from low-income countries has been a long-standing reason for the impasse in WTO negotiations to liberalize world trade.[87] SET management supports free trade where people with the least financial security get a greater share of the benefits.

3.4.3. Profits in a Global Context

The FBL Approach to Profits

The FBL management goal with regard to global profit is to maximize overall financial gains, with little regard for who receives them. Consistent with its consequential utilitarian ethic, the FBL approach is more concerned with total profit than with its distribution. Toward this end, international financial institutions that have made it easier for money to flow across borders have been an important factor in creating the increases in global GDP.[88] This flow of money is facilitated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an organization with about 200 member countries, which was established to promote orderly and stable international monetary exchange; foster international economic growth and high levels of employment; and provide temporary financial assistance to countries to help ease balance of payments problems. To meet these goals, the IMF monitors international commerce and provides financial and technical assistance.[89] This allows capital to move to where it receives the highest return, and limits national boundaries and governments from constraining economic investment. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF dispensed $650 billion to countries around the world in a successful effort to stabilize the global economy and return to economic growth.[90]

The TBL Approach to Profits

As noted earlier, TBL management is concerned with total profits but also with the growing income gap that results from practices associated with FBL management. There is extensive evidence that there is a widening gap between rich and poor, both within and between countries. For example, the income gap between United States and south Asia and Latin America has tripled since 1960. This is true not only in terms of absolute wealth (the richest 1.5 percent own 47.5 percent of the world’s wealth), but also in terms of income.[91] Recall that the richest 10 percent of the world take more than half of global income.

To address this widening gap, the TBL approach promotes the work of institutions such as the United Nations Global Compact, which is the world’s largest initiative for corporate sustainability and is built on principles of labor standards, the environmental protection, human rights, and anti-corruption. Research suggests that profits have increased for firms that sign on with the Global Compact, like the Tata Group and LEGO.[92] TBL management also aligns with the work of the World Bank, an organization that provides financial and technical assistance to reduce poverty in low-income countries.[93] The World Bank—owned by about 200 countries—provides interest-free credit, low-interest loans, and grants to low-income countries for purposes like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. Often these financial services have been linked to structural adjustment programs, which are designed to ensure that low-income countries have balanced budgets and play according to the rules of a free market. Promoting free market principles can serve the interests of high-income funding countries as much as—and sometimes more than—the economic interests of the low-income countries. For example, structural adjustment programs have discouraged subsidies and tariffs in low-income countries, making it difficult for them to compete with the subsidies and tariffs enacted by high-income countries. Because of this, it has been argued that structural adjustment programs have an unintended negative effect on the economies of low-income countries,[94] and that IMF programs may undermine human security.[95]

A major global trend intended to address the negative externalities associated with FBL management is the rise in socially responsible investing, where investment decisions seek to maximize “financial returns via strategically reducing negative social and ecological externalities.”[96] This includes ESG (economic, social, and governance) investing, and provides a welcome option for the over 80 percent of people who are interested in investing in firms that are socially and ecologically responsible.[97] By some estimates, over $30 trillion is invested in sustainable assets globally, with growth around 10 percent annually.[98] The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) supports these investment efforts and in 2024 released two new standards: one for general sustainability reporting and another for climate-related financial reporting. Both aim to “provide the right information, in the right way, to support investor decision-making and facilitate international comparability to attract capital.”[99] Overall, sustainable investment strategies seek to maximize profit in ways that lessen social and environmental externalities, and sustainable funds are often celebrated for outperforming traditional funds.[100] However, despite the enormous value of sustainability funds, there is little evidence that such investments are adding up to meaningful positive social and environmental change, and greenwashing remains a major challenge throughout the investment sector.[101]

The SET Approach to Profits

Compared to FBL and TBL managers, SET managers are more likely to recognize that the free flow of capital across borders has often not had the intended outcome of making everyone better off.[102] In fact, critics note that easing the flow of money has created several negative externalities. The vast majority of money being traded, and a lot of the profit being generated, does not contribute to productivity in any real sense. Consider the example of global $600 trillion-dollar derivatives market,[103] where people seek to earn a profit by speculating (similar to betting) on the future value of an asset (such as the future price of a stock, bond, currency or commodity) without owning the asset itself. As a simplistic analogy, even though a billion-dollar bet on the outcome of a Super Bowl game may increase economic activity, it does not grow food or sew garments. In fact, financial tools like derivatives have contributed to international recessions and to income inequality.[104]

The SET approach seeks to reform the flow of money so that it is better aligned with sustenance economics. Perhaps the most notable reformer is Nobel prizewinner James Tobin, who in the 1970s anticipated some of the difficulties that have arisen from the deregulated flow of capital and suggested a simple 1 percent tax on all foreign currency transactions. This tax would ensure that financial transfers were based more on “real” changes in production and market opportunities than on the speculative and acquisitive economics of investors. In other words, the Tobin tax favors SET investors who are interested in the long term and penalizes FBL traders who are looking for quick profits. For example, this would deter traders who purchase $100 million of Japanese yen only to sell them fifteen minutes later for a profit of $10,000 when their value increases by 0.01 percent (the profit from such a transaction would be insufficient to pay the Tobin tax—in this case, $1 million). The Tobin tax would also give national governments greater freedom to change interest rates in their jurisdictions. There is widespread agreement that the Tobin tax is theoretically brilliant, but it has yet to be implemented because it conflicts with the dominant understanding of the free movement of capital, consistent with an FBL approach.[105]

SET management is aligned with sustainable impact investing, where investment decisions “seek to optimize social and ecological well-being without a need to maximize financial returns.”[106] Indeed, as many as one-third of retail investors already willingly put social and ecological well-being ahead of maximizing financial returns.[107] Having access to such capital enables and compels managers to relax the need to maximize profits and instead place greater emphasis on making a positive impact. This is relevant for B Corps and for most of the SET businesses described in this book. Research suggests that if prior to making an investment decision, investors were asked about their views on sustainability, this would increase the likelihood that they would accept lower financial returns in favor of social and ecological returns.[108] Moreover, students who learn about FBL, TBL and SET approaches to management “allocate less money to investments that focus only on financial returns without regard for social and ecological well-being.”[109]

Test Your Knowledge

3.5. Entrepreneurial Implications

Having explained important concepts related to economic well-being, we now consider some business examples that illustrate the effect different approaches to entrepreneurship and management have on jobs, goods and services, and profits. Which forms of economic well-being, opportunities and kinds of entrepreneurial ventures are you most attracted to?

3.5.1. FBL Entrepreneurship and Economic Well-Being

The following opening sentence from an influential entrepreneurship textbook illustrates the strong connection between entrepreneurship and economic well-being: “Entrepreneurs everywhere endlessly create value for economies around the world.”[110] The drive for economic well-being may well be considered the engine of entrepreneurial activity, and entrepreneurship theory defines “monetization”—the generation of entrepreneurial reward and sustainable value—as the outcome stage of the entrepreneurial process.

As illustrated throughout this chapter, it is hard to deny the role of financially motivated entrepreneurship in creating vast numbers of jobs, endless development of goods and services, and increasing aggregate financial wealth as never before seen in human history. Nor is it a surprise that FBL thinking is characteristic of many entrepreneurs.

Most of the largest organizations and best-known entrepreneurs have embraced many aspects of FBL management. For example, consider Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, our exemplar of an FBL manager from Chapter 1, who withstood years of losses and modest profits to gain a dominant market position, thereby securing larger and longer-term financial returns. Despite the merits of low prices and same-day delivery (equaling more money and time for customers), Amazon has long been accused of engaging in unfair competition—for example, by taking losses to put competitors out of business, removing the “buy” button when platform vendors step out of line, and manipulating product search returns to prioritize Amazon’s house brands over third-party offerings.[111] Bezos is not alone. He, along with tech entrepreneurs and titans Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook), Tim Cook (Apple), and Sundar Pichai (Alphabet, Google’s parent company), faced US Senate antitrust hearings in 2020 against charges of monopolistic practices that harm the economy and society. Amazon was subsequently sued in 2023 by the Federal Trade Commission for illegally maintaining monopoly power, with a trial set for 2025.[112]

More generally, FBL entrepreneurship maintains a strong separation between business-oriented, profit-seeking activities versus socially or environmentally oriented, philanthropic activities. This can be observed in the “robber baron” industrialist era of the 1800s up to the present. The altruistic mark of that earlier generation lives on in such cultural landmarks as the Rockefeller Center, Carnegie Hall, and Vanderbilt University, which tend to mask the unethical, exploitative, and environmentally destructive business practices of their namesakes.[113] To some, Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft, represents a modern variation of this theme. The first of the great tech entrepreneurs, Gates was also a forerunner in the anti-competitive and monopolistic practices observed throughout the sector, of which Microsoft was convicted in a landmark 2001 antitrust lawsuit.[114] After leaving the company, Gates went on to create one of the largest philanthropic foundations in the world, devoting himself to issues of healthcare, extreme poverty, and education in the most disadvantaged regions of the world, and more recently to environmental and climate change efforts.[115] Thus, while FBL entrepreneurship has an impressive record in terms of economic well-being, it tends to be less sensitive to the deleterious consequences that accompany extreme wealth creation and concentrations of economic power, and to treat social and environmental issues as largely separate from the realm of business.

3.5.2. TBL Entrepreneurship and Economic Well-Being

By contrast, TBL entrepreneurship recognizes the inseparability of economic, social, and environmental well-being, and aims to address the negative externalities of profit-seeking activities. Jeff Bezos’s transition from FBL to TBL manager, as described in Chapter 1, is illustrative. For many years, and even after the company achieved great success, Bezos seemed unconcerned with environmental issues, gave little thought to his local community, and was widely criticized for his extremely limited philanthropic contributions.[116] Since adopting TBL thinking, however, Amazon has simultaneously promoted its ambitious and comprehensive sustainability agenda alongside its primary profit pursuits, as reflected in the company’s annual sustainability and financial reports.[117]

Walmart provides a complementary example, because like Amazon, the company has made the transition from FBL to TBL management. When it was managed according to FBL principles, Walmart became known for designing jobs that paid employees as little as possible (and often limited their hours to part time to minimize the need to pay employee benefits) and for pressuring suppliers to keep prices low (which created poor-paying jobs in the supplier organizations).[118] As a measure of the financial success of Walmart’s FBL management approach, consider that the wealth of the Walton family is equivalent to the total wealth of the poorest 130 million people in the United States.[119]

This final point merits further comment, as it draws attention to entrepreneurial opportunities related to the local multiplier effect, which refers to the enhanced financial well-being a community gains when it supports locally owned businesses.[120] In the example of Walmart, consider that for every dollar spent making a purchase from a national retailer, 14 cents stay in the local community (e.g., in the form of wages for clerks). In contrast, 52 cents of every dollar spent at a locally owned retailer stays in the community (e.g., wages for clerks and professionals, purchasing more locally-sourced products, and profits staying in the community). Along the same lines, for every new retail job that Walmart creates in a community, an average of 1.4 other jobs are lost in that community.[121] Note that there are also differences in types of jobs created by local versus nationally owned businesses, with locally owned firms being more likely to hire local professionals like accountants and marketers and information system experts. The more aware consumers are of how the local multiplier works, the more opportunities there are expected to be for local entrepreneurs.

Firms managed with the TBL approach often have effects on jobs, goods and services, and profits that are similar to those of FBL managed firms, but with reduced negative externalities in situations where it is profitable to do. This similarity comes from the fact that like the FBL approach, the TBL approach is focused on maximizing monetary profit. In other words, entrepreneurs with a TBL perspective seek social and ecological initiatives that promise financial gain. To continue with the example of Walmart, thanks to the intrapreneurial initiatives of then-CEO Lee Scott, Walmart has moved away its former FBL approach and is today considered a leading TBL organization, thanks to its innovations in reducing energy use and waste production. Each of these innovations reduced costs (and so increased profits). However, Walmart still faces criticism for its treatment of employees and is still looking to find better ways to profit from increasing job quality.[122]

3.5.3. SET Entrepreneurship and Economic Well-Being

Because it is not seeking to maximize financial well-being as its primary motive, the SET approach to entrepreneurship is remarkably different from the FBL or TBL approaches. Yvon Chouinard, the environmentalist and founder of the outdoor apparel company Patagonia, is a standout example of the SET mindset toward economic well-being (see also opening case, Chapter 10). With respect to jobs, Chouinard instituted an emblematic “let my people go surfing” policy, allowing employees to take breaks and do things like go surfing whenever they see fit (or whenever the surf is good!).[123] On the product front, Patagonia’s clothing is not only designed for functional durability, the company also offers in-house repair services and a platform for resale of used goods (known as Worn Wear) to extend their useful life and reduce waste. As a further statement against excess consumerism, Patagonia took out a now-famous full-page ad in the New York Times on Black Friday in 2011. The ad featured one of the company’s fleece coats and the headline “Don’t Buy This Jacket.”[124] Prior to that, in 2002 Chouinard established a nonprofit named 1% for the Planet, for like-minded businesses to donate 1 percent of total revenue (not profits, which are far less than overall sales) to environmental causes, which Patagonia had been doing since 1985. Today, 1% for the Planet has close to 5,000 business members in over 100 countries and has donated over $672 million to environmental partners.[125]

Patagonia has steadfastly stood for values other than profit seeking, but perhaps the most impressive indication of Chouinard’s SET leadership occurred in 2022, when the “reluctant billionaire” irrevocably transferred ownership of the company—and thereby his entire family wealth estimated at $3 billion—to a specially designed Purpose Trust and nonprofit entity whose singular objective is to help fight the climate crisis.[126] As in this chapter’s opening case, SET entrepreneurs do not see economic well-being as an end in itself but as a foundation for serving higher purpose. In a press release announcing the ownership transfer, Chouinard explained his motivation this way:

As the business leader I never wanted to be, I am doing my part. Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth, we are using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source. We’re making Earth our only shareholder. I am dead serious about saving this planet.[127]

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- There are two key varieties of capitalism:

- (i) documentational capitalism, which emphasizes detailed written contracts, public financial reports, management rights, and short-term maximization of financial performance; and

- (ii) relational capitalism, which emphasizes relational contracts, long-term reputation and financial performance, employee rights, and the needs of all stakeholder groups.

- There are two key varieties of economics:

- (i) acquisitive economics, which refers to managing property and wealth to maximize short-term monetary value for owners; and

- (ii) sustenance economics, which refers to managing property and wealth to increase long-term overall well-being for owners, members, and other stakeholders.

- Three key outcomes are typically used to measure success in terms of economic well-being: jobs, goods and services, and profit.

- When it comes to managing economic well-being in high-income countries:

- FBL management emphasizes creating jobs, maximizing productivity, and maximizing profits.

- TBL management emphasizes creating good jobs, pursuing sustainable development, and maximizing profits.

- SET management emphasizes creating jobs for people from all walks of life and paying a living wage, producing goods and services that meet real needs rather than endless wants, and maximizing the GPI (Genuine Progress Indicator).

- When it comes to managing economic well-being from a global perspective:

- FBL management emphasizes creating jobs for people facing income insecurity, practicing free trade, promoting the free flow of money, and maximizing global GDP (gross domestic product).

- TBL management emphasizes creating good jobs for people facing income insecurity, pursuing sustainable development, and maximizing global GDP through sustainable/ESG (economic, social, and governance) investments.

- SET management emphasizes creating jobs that pay a living wage, practicing fair trade that benefits people facing income insecurity, and directing profit toward long-term (non-speculative) investments and circulation within local communities.

- Entrepreneurs reflect and reinforce these emphases, with FBL- and TBL-oriented entrepreneurship seeking maximum financial return, while SET-oriented entrepreneurship addresses societal expectations and ecological needs regarding jobs, goods and services, and profits.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Does the country you live in place greater emphasis on documentational or on relational capitalism? Do you see that changing during your career? Why or why not? What effect do you think this has on what is taught in business schools in your country? Explain your reasoning.

- Modern acquisitive economic theory assumes that people will act in a self-interested way and will cheat to get what they want. Do you think this assumption is based on a realistic and full appraisal of human nature? Do you think people are more likely to cheat when they are expected to? How do you react when people don’t trust you to act with integrity?

- Many proponents of free trade are selective in their views. For example, they promote the free flow of money and goods and services but do not support the free flow of labor across national borders (even though the free flow of economic assets should include people being free to move from one country to the next, as in the EU). What are the implications of such a selective view? What would be pros and cons of free flow of labor? Would they be different for low-income than for high-income countries?

- Which do you prefer, free trade or fair trade? Explain your reasoning.

- What is the difference between GDP and the GPI? Given that the economists who developed the GDP measure did not intend or want it to be used as a measure of economic well-being, why do you think it has become so popular? What changes would you expect if the GPI became the new norm? How likely is that to happen?

- Most people would agree that business should enhance financial well-being by creating jobs, providing goods and services, and being profitable. However, the criteria used to evaluate what it means to enhance financial well-being differ depending on one’s management approach (FBL, TBL, or SET). Describe the criteria or standards used by each management approach for each of the three elements (jobs, goods and services, profits). Which approach is closest to your own view of what “enhancing financial well-being” means? Explain.

- TBL management proposes to address social inequality and climate change through socially responsible investing by directing funds toward companies with higher sustainability and ESG rankings. Do you believe this approach has been or will be effective, and what evidence is your assessment based on? Do you think it is affected by greenwashing? What examples of greenwashing have you personally seen?

- The third-most important reason entrepreneurs give for starting a new organization is to enhance financial well-being. Based on this chapter, which elements (jobs, goods and services, or profits) would you most want to achieve and which management approach would you use if you were to start a new business? Describe how you might be able to address this in a new start-up.

- Reimer, B. (2024). In Assiniboine Credit Union [Video]. Produced by Savanna Vagianos as part of SET research group, filmed by N. Ridley. Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJhB8KAv2HU ↵

- Maddock, R. (2015, February 5). Why do people hate bankers? No, really. . . The Conversation. Retrieved December 18, 2024, from http://theconversation.com/why-do-people-hate-bankers-no-really-36342 ↵

- Halstead, J. (2021). The inspiring life of Ed McCaffrey, one of ACU’s founding members. Asterisk. https://blog.acu.ca/the-inspiring-life-of-ed-mccaffrey-one-of-acus-founding-members/ ↵

- ACU. (n.d.). ACU—About. Retrieved December 20, 2024, from https://www.acu.ca/en/about ↵

- Loxley, J. (2003). Financing community economic development in Winnipeg. Économie et Solidarités, 34(1): 82–104. https://ciriec.ca/pdf/numeros_parus_articles/3401/ES-3401-06.pdf ↵

- Longhurst, J. (2024, May 21). Muslim community optimistic about alternative financing plan. Winnipeg Free Press, p. B3. ↵

- Assiniboine Credit Union. (2023). Building community: Annual impact report 2023 (pp. 1–19). ↵

- Reimer, B. (2024). ↵