Part 2: Planning

7. The Decision-Making Process

- Learning Goals

- 7.0. Opening Case: Can Rational Management Decisions Be Immoral?

- 7.1. Introduction

- 7.2. Step 1: Identify the Need for a Decision

- 7.3. Step 2: Develop Alternative Responses

- 7.4. Step 3: Choose the Appropriate Alternative

- 7.5. Step 4: Implement and Monitor the Choice

- 7.6. Entrepreneurial Implications

- Chapter Summary

- Questions for Reflection an Discussion

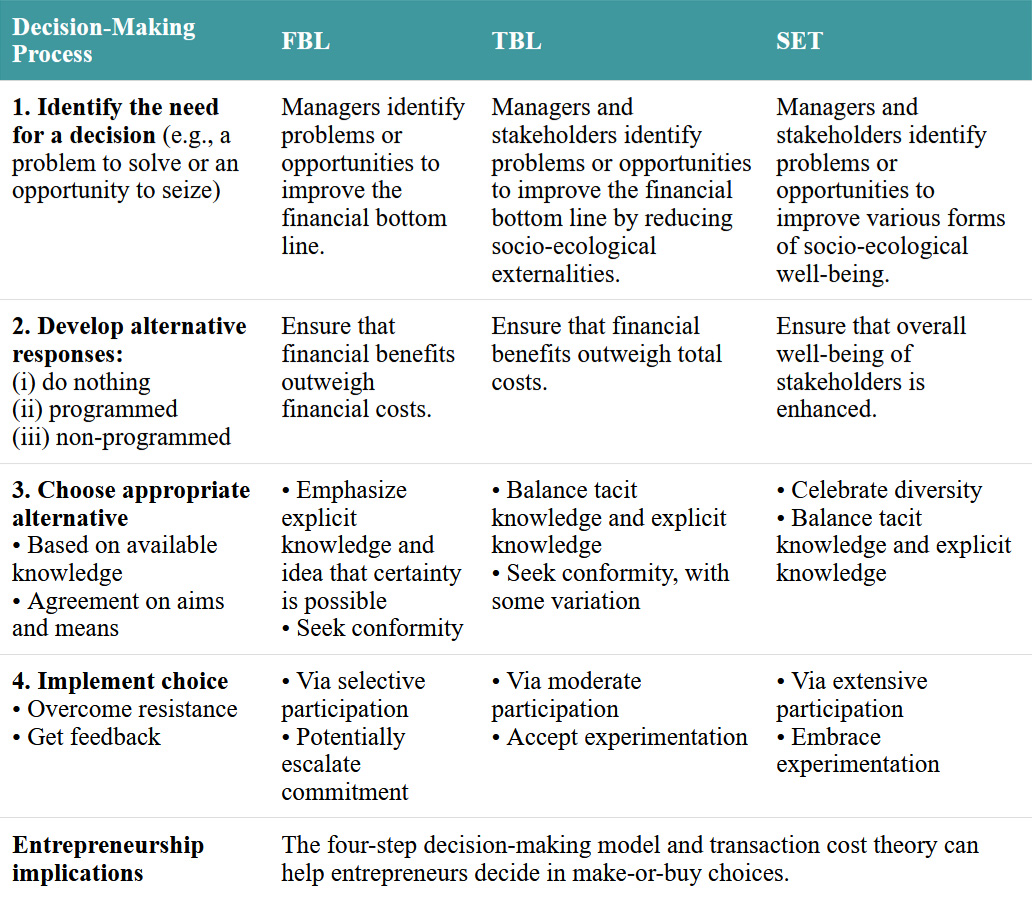

Chapter 7 provides an overview of the four steps of decision-making, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- List and explain the four steps of the decision-making process.

- Describe the key differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches to decision-making.

- Differentiate between programmed and non-programmed decisions.

- Explain how two factors—the level of agreement on aims and means, and available knowledge—influence the decision-making process.

- Recognize how organizational scripts influence the decision-making process.

- Explain what escalation of commitment is and why it occurs.

- Explain what entrepreneurs should consider when deciding which goods and services their organization will make, and which they will buy from suppliers.

7.0. Opening Case: Can Rational Management Decisions Be Immoral?

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you had to decide between doing the “right thing” versus doing what you thought your employer wanted you to do? Have you ever been so taken up by the rewards of business as usual that you found yourself acting against your morals? How does this happen? A classic example involves a manager named Dennis Gioia and his experience working at the Ford Motor Company over fifty years ago.[1]

In the early 1970s, the Ford Motor Company introduced its $2,000 Pinto car to compete against the low-priced Volkswagen Beetle. To reduce costs, the Pinto engineers decided to locate its fuel tank over the rear axle. Unfortunately, this decision proved problematic. After several years, the data suggested that the fuel tank’s placement made the Pinto prone to explosions when the car was hit from behind.

Imagine that you are Ford’s Field recall coordinator and these data have been brought to your attention. You immediately recognize that a decision needs to be made, and you consider two options. The first option is to recall all 12.5 million Pintos on the road and install an $11 safety bladder. The estimated total cost of this option is $137.5 million. The second option is not to recall the vehicles and instead pay the damages that arise from lawsuits. Using data provided by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Transportation Administration, you estimate that the total lawsuit costs would be $49.5 million ($200,000 for each of the 180 anticipated burn deaths, $67,000 for each of the 180 anticipated burn injuries, and $700 for each of the 2,100 anticipated burned vehicles). The numbers are clear and compelling, so you choose and implement the second option, which will save Ford $88 million compared to the first option.[2]

Unfortunately, this account is based on a true story: managers at Ford made the decision to not recall the Pinto. When the general public found out, it was outraged. In February 1978, a California jury was so upset by Ford’s cost-benefit analysis that it awarded one accident victim $125 million in punitive damages.[3]

How is it that managers’ so-called rational decision-making processes can result in a decision that many people find morally offensive? People tend to blame the individual manager(s) who make such decisions. But it turns out that many people facing a similar situation would likely make the same decision. Consider what happened to Dennis Gioia, the manager who worked as Ford’s recall coordinator on the Pinto file. Prior to joining Ford, when he was still an MBA student, Gioia was often critical of the conduct of profit-maximizing businesses:

To me the typical stance of business seemed to be one of disdain for, rather than responsibility toward, the society of which they were prominent members. I wanted something to change. Accordingly, I cultivated my social awareness; I held my principles high; I espoused my intention to help a troubled world.[4]

Gioia’s MBA classmates were dumbstruck when he accepted a job offer from Ford, because doing so seemed to go against his values:

I countered that it [working at Ford] was an ideal strategy, arguing that I would have a greater chance of influencing social change in businesses if I worked behind the scenes on the inside, rather than as a strident voice on the outside. It was clear to me that somebody needed to prod these staid companies into socially responsible action. I certainly planned to do my part. Besides, I liked cars.[5]

When he joined Ford, Gioia was definitely not a typical FBL manager, and probably the last person in his graduating class that anyone expected to choose money over lives.[6] So what happened? Gioia describes how he was resocialized at Ford while competing for attention with other MBAs who had recently joined Ford: “The psychic rewards of working and succeeding in a major corporation proved unexpectedly seductive.” Soon the basic routines at Ford—the “scripts” that managers learned and followed—and the company’s normal ways of doing things became second nature to Gioia. His job was intense and involved overseeing about 100 active recall campaigns. Routines were important aids in managing the heavy caseload and making decisions.[7]

In his early days on the job, Gioia took very seriously the fact that his job literally involved life-and-death decisions, but

that soon faded . . . and of necessity the consideration of people’s lives became a fairly removed, dispassionate process. To do the job “well” there was little room for emotion. Allowing it to surface was potentially paralyzing and prevented rational analysis about which cases to recommend for recall. On moral grounds I knew that I could recommend most of the vehicles on my safety tracking list for recall (and risk the label of a “bleeding heart”). On practical grounds, I recognized that people implicitly accept risk in cars.[8]

The routines that he inherited in his position seemed practical and rational (from an FBL perspective). They provided Gioia with ways of behaving and making decisions. As well, he lacked well-developed scripts to enact his alternate values.

In retrospect I know that in the context of the times my actions were legal (they were all well within the framework of the law); they were probably also ethical according to most prevailing definitions (they were in accord with accepted professional standards and codes of conduct); the major concern for me was whether they were moral (in the sense of adhering to some higher standards of inner conscience about the “right” actions to take).[9]

In short, scripts and routines have a powerful effect on how decisions are made. Unless managers are mindful when making decisions, they will default to the scripts they are given.[10] Decisions that are appropriate according to an FBL or TBL perspective may seem immoral from a SET perspective, and vice versa. For example, from an FBL moral point of view, recalling the Pintos might have been considered unethical because $88 million of “extra” costs would have been imposed on shareholders. In contrast, a SET perspective would agree with the general public’s sentiment that Ford had a responsibility to issue the recall.

7.1. Introduction

Managers must make many important decisions in carrying out each of Fayol’s four functions of management (see Chapter 1). A decision is a choice that is made among a number of available alternatives to address a problem or opportunity. Decisions must be made about what goals, plans, and strategies to pursue (planning); what sorts of organizational structures and systems to design and implement (organizing); how to motivate and communicate with others (leading); and the values and meaning that will provide guidance to organizational members (controlling).

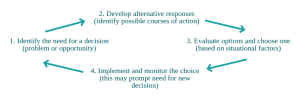

Because everyone makes multiple personal and professional decisions every day, it is helpful to develop a better understanding of how decisions are made and how the decision-making process can be improved. In this chapter, we examine in detail each of the four steps of the decision-making process (see Figure 7.1), describing differences between a Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) perspective.

Figure 7.1. The four-step decision-making process

7.2. Step 1: Identify the Need for a Decision

The first step of the decision-making process involves identifying the need for a decision to be made. A decision is often necessary if a problem is detected in some current activity, or if there is an opportunity to engage in a new activity. Since managers are constantly confronted with both problems and opportunities, they must constantly make decisions. To avoid being overwhelmed, managers filter problems and opportunities to determine which ones require a decision now and which can be delayed or even ignored. For example, a decision is more likely to be seen as necessary if the viability of the organization is at stake, or if previous similar events have always prompted a decision.

Managers, like all people, use cognitive scripts when they make decisions, akin to the way actors use scripts to know what to do and say in specific scenes.[11] People have scripts for a variety of settings, from knowing what to do and say when meeting strangers, to proper table manners and etiquette, to driving a car. For example, drivers read road signs, follow routines to determine if it is safe to change lanes, and adjust their speed for weather and traffic. Disastrous outcomes may occur if drivers have limited experience in recognizing potential dangers or are distracted from their scripts by their phones.

Managers use learned scripts to recognize (or fail to recognize) whether a situation requires a decision. They learn to pay attention to key financial reports, productivity data, consumer trends, and so on. As illustrated in this chapter’s opening case, scripts help managers recognize the need for a decision, but they may also cause managers to make inappropriate decisions.

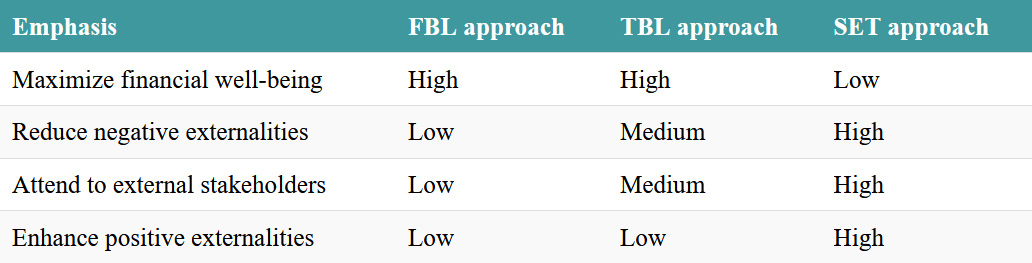

Just as there are different genres of movie scripts—action, comedy, romance, horror, and so on—so also there are different generic scripts for FBL, TBL, and SET management (see Table 7.1). The scripts for FBL management focus on financial well-being and tend to be oriented toward an individual company’s situation. Managers focus on solving problems and seizing opportunities that will increase a firm’s revenues or reduce its financial costs, usually with little regard to whether a decision creates positive or negative socio-ecological externalities. Those involved in the Ford recall decision in the opening case followed an FBL script and did not have TBL or SET scripts to draw upon.

Table 7.1. Relative emphases in scripts for identifying the need for a decision

TBL scripts are similar to FBL scripts in terms of enhancing financial well-being, but TBL scripts differ in two ways. First, they are much more attuned to finding ways to reduce existing negative socio-ecological externalities when it enhances the firm’s financial well-being. Second, they are more likely to be prompted by external stakeholders. Therefore, a comparatively wider set of concerns can trigger the decision-making process for TBL managers. Compared to FBL managers, TBL managers are more sensitive to the needs of other stakeholders and are committed to putting those needs on the decision-making agenda.[12] For example, in light of exploitive working conditions in low-income countries, managers in a growing number of organizations have voluntarily chosen to adopt an international standard of social accountability (SA8000), where adherents agree to pay wages that are adequate to cover basic needs and not just the legislated minimums.[13] These organizations also refuse to employ children under fifteen years of age and do not use forced labor. Knowing that adopting these higher standards could reduce the risk of a negative brand image, large TBL retailers have committed themselves to choosing suppliers that follow these standards, even if they are not offering the lowest price. For example, the large retailer Inditex committed to stop dealing with its Myanmar suppliers when managers discovered labor rights violations following political changes in the country.[14]

SET management scripts share and extend the emphasis that TBL scripts place on attending to external stakeholders and reducing negative socio-ecological externalities, but SET scripts differ from TBL scripts in two additional ways. First, SET scripts place a greater emphasis on enhancing positive externalities by seeking out and trying to address society’s vexing problems. Second, unlike FBL and TBL approaches, SET scripts may lead to decisions that enhance certain non-financial benefits (e.g., employee satisfaction), even if doing so does not yield financial or productivity benefits. For example, AT&T manager Robert Greenleaf noticed that the decision-making scripts used in recruitment and promotion at his company were resulting in women being under-represented in its workforce, and in African American employees being promoted at a slower rate than their white co-workers. Because issues like these were not perceived to be associated with AT&T’s financial well-being at the time, a manager with an FBL or TBL perspective would not have identified them as problems or opportunities. However, because of his SET approach to management, Greenleaf recognized them as issues calling for decisions to be made, and this prompted him to work with others to develop new scripts to address them. These new scripts eventually became the new norms and guidelines that informed subsequent decision-making at AT&T.[15]

Recognition that there is a need for a decision in a particular situation is influenced by whether a manager is using scripts based on the FBL, TBL, or SET approach. Suppose a manager receives information that a very profitable product the company is selling is potentially dangerous to the health of customers (e.g., the Ford Pinto). An FBL manager may not feel a decision is necessary because the situation is only “potentially” dangerous, whereas a SET manager who is confronted with the same information would likely decide to start the decision-making process to reduce the potential for harm to customers. Managers in companies that sell carbonated soft drinks and/or fast food face a similar dilemma of attending to the financial well-being of their company versus the health of their customers, since both products have been implicated in childhood obesity.[16]

Test Your Knowledge

7.3. Step 2: Develop Alternative Responses

Once the need for a decision has been established, the next step is to develop alternatives for addressing the problem or opportunity that has been identified. In the most general sense, managers can respond in one of three ways:

- Do nothing;

- Apply an existing routine (i.e., make a programmed decision); or

- Develop a new routine (i.e., make a non-programmed decision).

The first approach—“do nothing”—is the appropriate response in situations where action is not worth the effort or the cost. For example, doing nothing might be the appropriate response if someone arrives late at work on account of an unexpected traffic jam.

The second approach involves following an existing script or routine. Doing so results in making programmed decisions (also called routine decisions). In a programmed decision, the response to an organizational problem or opportunity is chosen from a set of standard alternatives. For example, organizations have numerous routines for things like reordering office supplies, responding to employees who arrive late for work, dealing with irate customers who do not receive their order on time, and so on. These decision rules and policies have been developed to simplify the handling of situations that recur frequently.

Sometimes managers may be tempted to use the easiest script instead of choosing the most appropriate script. This may happen if using the most appropriate script requires extra time and effort. For example, if an employee arrives late for work, the easiest response is to ”do nothing” or to follow a simple script to “dock the employee’s pay.” However, if someone arrives late for work repeatedly, the manager is well-advised to find out what is causing the behavior (perhaps the employee’s child is sick, or the employee is fearful of a conflict with a co-worker, or the employee is simply irresponsible). A different script may be appropriate in each case.

The third approach is to make a non-programmed decision. A non-programmed decision involves developing and choosing a new way of dealing with a problem or opportunity. The quality of non-programmed decisions often depends on the time and resources a manager is willing to invest in developing them.[17] The amount of time and resources invested in making non-programmed decisions increases with the perceived importance and newness of the decision, and decreases with the urgency of the decision. Increased time is needed for strategic decisions such as responding to a new competitor, coping with changes in legal regulations, or deciding whether or not to go ahead with a major expansion. Some non-programmed decisions may be developed for a one-of-a-kind situation (for example, where to locate a new company headquarters), whereas other non-programmed decisions will become new scripts to be used in future programmed decisions. When smartphones first became commonplace in organizations, guidelines were needed on issues like whether employees were expected to respond to business emails during evenings and weekends, whether employees could use a company phone for personal matters, and so on. Once these non-programmed decisions were made, they became the new norm for programmed decisions in subsequent years.[18]

Consider how the three possible responses (do nothing, make a programmed decision, or make a non-programmed decision) played out in a situation that confronted Nils Vik, the owner of a small café called Parlour Coffee in inner-city Winnipeg. One evening the police called to tell Vik that his business had been broken into. His first reaction was to do nothing, since he was at home with his young children, and didn’t want to go to the shop to clean up the mess (of course, the do nothing option wasn’t realistic in the long term; he eventually needed to go to the shop and address the mess). His second response was more along the lines of a programmed response that you might expect from any shop owner in his situation: he installed an alarm system. But after installing the alarm, he started thinking about the situation facing the person(s) who had broken into his shop: “I couldn’t help but think . . . man, you have to be in pretty rough shape that you think the best means of acquiring some income is to break in somewhere in the middle of the night.” Upon further reflection he realized that installing his alarm system only addressed a symptom of the problem by shifting the potential for break-ins to someone else’s business. “So if we want to try and make any lasting change, we have to prevent these things from happening at the root cause. Clearly it has to do with inequality and income disparity and poverty. Those things an alarm system can’t fix.” Eventually Vik decided to donate a percentage of his sales for the rest of the year to a not-for-profit agency that provides support and shelter for homeless people in his neighborhood.[19] Thus, his third action involved making a non-programmed decision.

Test Your Knowledge

7.4. Step 3: Choose the Appropriate Alternative

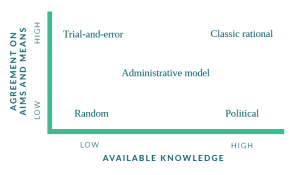

The third step—choosing the best alternative—lies at the heart of the decision-making process. This step has two highly interrelated sub-steps, namely evaluating the different alternatives developed in step 2, and then selecting the best alternative. A systematic evaluation of the relative merits of the alternatives is particularly important for strategic and non-programmed decisions. How a choice is made depends on two key factors: (1) the quality of knowledge available to decision-makers about the outcomes that are likely to result with each of the alternatives; and (2) the level of agreement among decision-makers regarding an organization’s aims and the best means to achieve those aims. These two factors can be combined to form the two-dimensional framework shown in Figure 7.2. The figure also shows five general approaches decision-makers use as they choose among possible alternatives. We first explain the two dimensions of the figure, and then describe each of the five general approaches.

Figure 7.2. Five approaches for evaluating options and choosing one

7.4.1. Available knowledge

As shown along the horizontal dimension of Figure 7.2, the decision-making process is influenced by the knowledge that is available to decision-makers. Three factors are important regarding the available knowledge:

- Is it possible to identify an optimal choice?

- Do decision-makers have good knowledge about the likelihood and payoffs of each possible outcome? and

- Is the knowledge explicit or tacit?

We will examine each of these questions in turn.

Is it possible to identify an optimal choice?

Many decisions are dilemmas, meaning that no optimal choice can be made because there are both positive and negative aspects associated with each alternative, and the resulting trade-offs are complex and defy complete analysis.[20] Examples like choosing the best strategy to implement, the best idea for a new start-up, the best romantic partner, the best neighborhood to live in, and the best career to pursue are all dilemmas. In partial dilemmas, decision-makers have enough knowledge to make informed decisions (i.e., decision-makers may not know which is the best idea for a start-up, but they do have enough experience in the industry to discern between better and worse ideas). In total dilemmas, decision-makers do not have enough information to predict with any confidence which choices might be better than others.

Do decision-makers have good knowledge about the likelihood and payoffs of each possible outcome?

Unless they are facing a total dilemma, decision-makers usually have some knowledge about the risks associated with a choice. Managers make decisions in situations that range from uncertain to certain (see Figure 7.3). Certainty exists when managers know exactly what outcomes are associated with each alternative they are choosing among, the possible payoffs associated with each possible outcome for each alternative, and the probability that each payoff will occur. This situation is obviously rare in business decisions. At the other extreme, uncertainty exists when managers do not know what outcomes are associated with each alternative they are choosing among, do not know the possible payoffs associated with each possible outcome for each alternative, and do not know the probability that each payoff will occur. This type of situation is also uncommon, but more common than certainty. Some new start-ups, for example, may face an extreme amount of uncertainty. In between certainty and uncertainty is a wide area of risk. Risk is evident when decision-makers have at least some knowledge about the likelihood of the different possible outcomes that might occur if they choose to implement a particular alternative, and the payoffs associated with each outcome.[21] Risk involves decisions where managers are able to develop some (but not all) alternatives, estimate (but not know for certain) payoffs for each alternative, and estimate (but not know for certain) the probabilities of the payoffs. Thus, there is no way to guarantee that choosing a particular alternative will lead to a particular outcome or payoff. This is obviously the situation faced by most business most of the time.

Figure 7.3. Continuum of uncertainty, risk, and certainty in decision-making

To illustrate these ideas in a business setting, imagine that you work for an investment firm, and that you must decide which one of five entrepreneurial business plans to invest in. Which venture you choose will be based on your best attempt to answer a host of questions, including the following: Will there be sufficient demand for the firm’s goods and services? Has the product been fully developed? What sort of marketing strategy is best? What management and technical skills does the new start-up require? How profitable will it be? What kind of socio-ecological externalities will it generate and address?[22] You will likely not have full knowledge about any of these matters, but you may be reasonably confident about the answers to some of these questions. In the end there may not be one clear best choice to make, especially if you invoke multiple measures of performance. Your decision is a dilemma characterized by a moderate amount of risk.

Scripts are important for understanding how decision-makers interpret and perceive the knowledge that is available to them. For example, in the 1950s, Ford spent ten years and more than $250 million in production and marketing costs (the equivalent of over $2 billion in today’s dollars) in order to develop a car called the Edsel (named after the owner’s son). As the manager of market research noted: “History had never witnessed anything like it before. More money was spent in its launching than any other previous product offered upon the consumer market anywhere. It was to be the most perfectly conceived automobile the world had ever seen, with every part of its planning guided by public opinion polls, motivational research, Science.”[23] Despite this great attention to optimizing certainty and reducing risk, the Edsel was a failure. Why? Because Ford managers took all this available knowledge and interpreted it using their pre-existing scripts, “ignoring data in order to support their worldview and their position within managerial career hierarchies.”[24] In other words, available knowledge may be ignored or perceived as irrelevant.

A modern example of this knowledge limitation is found in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in decision-making. AI is able to find patterns in huge volumes of data, but it is limited by the scripts and systemic biases embedded in those data and the scripts used to interpret them.[25] For example, when Amazon found that a hiring algorithm favored applications that included words like “captured” or “executed” (which were most common on men’s resumes), it stopped using that algorithm.[26]

The scripts used by FBL, TBL, and SET management may influence whether a decision is perceived to have an optimal solution, and what risks and uncertainties it includes. The FBL script in the Ford Pinto case focused on the financial costs associated with each option but did not take into account possible damage to the company’s brand image (which may have been included in a TBL script), or the trauma of victims (which may have been included in a SET script).

Is the available knowledge tacit or explicit?

In addition to the amount of knowledge available, the decision-making process is also influenced by the nature of the knowledge and whether the knowledge is tacit or explicit. Explicit knowledge is information that can be codified or articulated. Explicit knowledge includes data found in financial statements, manuals on how to operate technology, and an organization’s business plan. Programmed decisions are often related to the availability of extensive explicit knowledge. For example, a firm’s programmed decisions related to bookkeeping and accounting practices are based on explicit knowledge drawn from generally accepted accounting principles, and these decisions in turn create a lot of explicit knowledge embedded in financial statements. This sort of explicit knowledge allows decision-makers to reduce uncertainties and understand the risks associated with both major decisions (e.g., expansion overseas, dropping an existing product line, purchasing another company) and minor decisions (can we afford to purchase new computers, which computer supplier offers the best prices and warranties).

Tacit knowledge is information or insight people have that is difficult to codify or articulate. Intuition is an example of how tacit knowledge may be used. Following one’s intuition refers to making decisions based on tacit knowledge, which can be based on experience, hunches, or “gut feel.” Experienced managers and experts are valued for their tacit knowledge. Instances of intuitive decision-making are especially striking when they counter explicit available knowledge. For example, Ray Kroc’s accountant advised him against purchasing McDonald’s, but Kroc had a “gut feel” that this investment would turn out to be a winner.[27] Similarly, the owner of Parlour Coffee felt that donating a portion of sales revenues to an agency that helps homeless people was the right thing to do. Decision-makers are more likely to rely on tacit knowledge when explicit knowledge is not available, and when making non-programmed decisions. Programmed decisions are often based on explicit knowledge and create explicit knowledge that perpetuates those decisions, but non-programmed decisions often involve choices that decision-makers have little explicit knowledge about.

FBL, TBL, and SET decision-makers all draw on both explicit and tacit knowledge. However, there are two reasons why SET decision-makers may be more likely to rely more heavily on tacit knowledge. First, because FBL and TBL approaches have been popular for quite a while, there has been more opportunity to develop the sorts of explicit knowledge that they use. Second, FBL and TBL approaches tend to place a greater emphasis on things that can be measured, in contrast to the more holistic SET approach, which places greater value on more difficult-to-codify ideas such as meaningful work and treating the environment with care.

7.4.2. Agreement on Aims and Means

As shown in Figure 7.2, the level of agreement on organizational aims and means that exists among decision-makers is the second key dimension to understanding how decision-makers choose among various alternatives. Agreement on aims and means refers to the level of consensus among decision-makers about the goals of an organization and the best way to achieve those goals.[28] Goals are the objectives or desired results that members in an organization are pursuing, and means are similar to plans, which describe the steps and actions that are required to achieve goals. Low agreement on aims and means indicates that there is considerable debate about what the aims should be and/or about the best means to achieve those aims. These disagreements may exist because different members identify problems or opportunities an organization is facing in different ways (step 1 of the process). For example, even among FBL and TBL managers who agree that maximizing shareholder financial well-being is the ultimate aim, there may be considerable disagreement about the best means of doing so. This was the case with the famous Saturday Evening Post magazine, where some managers wanted to maximize sales revenue, others to reduce costs, others to optimize the profit margin, and others to invest in research and development.[29] Such disagreements, and a failure to understand how these sub-aims were related to each other, contributed to the demise of the 150-year old publication in 1969.[30]

FBL and TBL approaches generally share a high level of agreement that aims should improve financial well-being, but there is less agreement about means, particularly with the TBL approach because it includes factors related to social and ecological well-being, and this creates added complexity. Whereas FBL managers may give little thought to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, TBL managers may want to reduce those emissions and may also have debates about whether the best way to do that is to purchase a fleet of electric vehicles or to develop wind or solar power sources.

On the face of it, we might expect the SET approach to have the lowest level of agreement in terms of both aims and means. In its aims, SET management seeks to enhance both social and ecological well-being, which can be considerably more complex than focusing on enhancing financial well-being (as in FBL and TBL approaches). A similar situation is evident in terms of means, where the potential for disagreement is likely higher with the SET approach simply because of the added complexity that develops when an organization seeks to reduce negative externalities and enhance positive externalities.

This problem may be reduced to some degree, since SET managers are more willing to accept and even embrace disagreements (see Chapter 16). Whereas FBL and TBL approaches make an implicit assumption that it is ideal to have complete agreement on aims and means (even if this ideal is seldom realized), this assumption does not hold in the SET approach, where decision-makers accept that the world is simply too complex for there to be one “best” set of aims and means.

To elaborate, a SET approach suggests that embracing diversity in aims and means will contribute to overall organizational performance, while the traditional FBL and TBL approaches indicate that uniformity in aims and means will enhance an organization’s financial performance. It turns out that research provides some empirical support for SET as well as for FBL and TBL views on the effect of disagreement about aims and means.[31] Consistent with the SET view, the level of agreement is negatively related to organizational performance measures (including how well the organization performs its main function). However, consistent with FBL and TBL approaches, the level of agreement is positively related to individual-based measures of performance (including their financial contributions).

7.4.3. Five Approaches to Decision-Making

Now that we have discussed the two dimensions of Figure 7.2—available knowledge, and level of agreement on aims and means—we can take a closer look at each of the five general approaches to decision-making that are used by managers: classical, political, trial and error, random, and administrative.

Classical Rational (High Agreement, High Knowledge)

The classical rational decision-making approach involves listing all possible options, determining the costs and benefits associated with each, and then choosing the best option.[32] This method tends to assume that decisions are made in conditions of certainty, that there is a best choice to be made, and that explicit knowledge is more valuable than tacit knowledge.[33] The classical rational method has traditionally been a favorite of FBL management, but it has been criticized for its unrealistic assumption that there can be agreement on aims and means, complete information, and the ability to compute and analyze all of the information.[34] That said, management practices are arguably getting better at facilitating agreement,[35] and improvements in information systems and technologies—particularly AI and machine learning systems—are getting better at providing increasing amounts of data and data processing capacities.[36] AI’s ability to process large amounts of information can significantly enhance decision-making effectiveness and automation, especially when managers are able to balance machine efficiency with human judgment through sequential and aggregated decision-making processes.[37] Nonetheless, even with improvements related to AI, research shows that organizations still face important barriers to using it, including transparency concerns, regulatory challenges, and the need to maintain human social dynamics.[38]

Over the years a wide variety of tools have been developed for managers who want to use the classical approach to decision-making, including decision trees, break-even analysis, inventory and supply chain management models, and various techniques in the field of management science, to name just a few. Sometimes such tools developed for the classical rational approach are adapted and used in other decision-making quadrants.

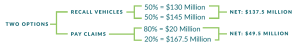

We can use the opening case to briefly highlight decision trees as an example of how this approach might be used. Imagine that in the case of the Ford Pinto, managers did not know exactly how many customers would bring in their car if the company decided to offer a recall (and thus how costly the recall would be). But based on information about previous recalls, the managers predicted that there was a 50 percent chance the recall costs would be $130 million and a 50 percent chance the costs would be $145 million. As shown in Figure 7.4, the expected costs would be $137.5 million (0.50 × $130 0.50 × $145). Similarly, let’s assume the decision-makers did not know for certain how many people would have an accident because of the design flaw, nor did they know what the actual costs of lawsuit claims would be. But based on past experience, they predicted that there was an 80 percent chance that total claims would be $20 million and a 20 percent chance that claims would cost 167.5 million. The expected cost would therefore be $49.5 million (0.80 × $20 million) (0.20 × $167.5 million). Based on strictly financial considerations, they would choose to pay the expected claims, because $49.5 million is a lot less than $137.5 million.

Figure 7.4. Example of a simple decision tree

Finally, even with the new information processing technologies, full-fledged rational decision-making techniques are evident in only a minority of managerial decisions.[39] In particular, it is rare to find situations where managers have complete information at their disposal and where no dilemmas are evident. Even as AI systems advance in their ability to process data and support decision-making,[40] the fundamental challenges of incomplete information and bounded rationality persist. Moreover, as illustrated in the opening case and the case of the Ford Edsel, poor decisions may be made even in situations where managers think that they have all the information they require to make a rational decision. Given the increased complexity associated with socio-ecological externalities, and the reality that many decisions faced by SET organizations do not have one best answer, this method may be least likely in SET management (and most likely in FBL management).

Political (Low Agreement, High Knowledge)

The political decision-making approach involves negotiations about which means and ends to pursue, identifying costs and benefits associated with various options, with the final choice often reflecting a compromise that partially satisfies the competing interests of those involved. In this method, disagreement among decision-makers can be intense, even when there is agreement that the overarching goal is to maximize the financial interests of shareholders. For example, suppose there are three ways—increasing sales revenues, reducing production costs, and developing more technologically advanced products—that are expected to be equally effective in increasing shareholder value by 10 percent. It is likely that marketing managers will prefer the option that focuses on increasing sales revenue, that manufacturing managers will prefer the option that focuses on reducing production costs, and that research and development managers will prefer to develop the most technologically advanced product. Often these competing alternatives will be mutually exclusive, or the organization will lack the resources to pursue all of them at the same time.

Such situations often lead to a politicized decision where a variety of tactics may be used as different managers try to achieve their own preferred outcomes. These tactics include (but are not limited to) the following:

- networking (ensuring that one has many friends in positions of influence)

- compromise (giving in on an unimportant issue in order to gain an ally who will support you when an issue that is important to you comes up)

- image building (engaging in activities that are designed to improve one’s image)

- selective use of information (using certain information to further one’s career)

- scapegoating (ensuring that someone else is blamed for a failure)

- trading favors (such as when a marketing manager agrees to support the manufacturing manager this year but expects a favor in return next year)

- forming alliances (agreeing with key people that a certain course of action should be taken)[41]

The political decision-making method may be especially likely when decision-makers are seeking to enhance their own power, status, and financial interests. This is often assumed to be the case in traditional FBL and TBL management, since these approaches assume that individuals are motivated by self-interest.[42] When employees perceive managers to be acting politically, anxiety increases, job satisfaction decreases, and managers are judged as being ineffective.[43]

In SET organizations, it is more likely that managers are willing to forgo their own gain in order to enhance positive social and ecological externalities, and debate with other decision-makers about the best ways of doing so. Decision-makers in such organizations may still participate in trading favors, forming coalitions, and building alliances, but the nature of this political behavior is qualitatively different because it is not as self-serving. Rather than politicking to enhance their own interests, though that will still happen in SET organizations, decision-makers are politicking on behalf of others and developing a more well-rounded understanding of externalities in the process.[44]

Trial and Error (High Agreement, Low Knowledge)

The trial and error decision-making approach involves listing possible options to choose from, attempting to determine the costs and benefits associated with each, and then choosing the option that offers the greatest opportunity for improvement with the lowest chance of making a mistake. For example, managers may agree that they want to increase the sales of their key product via advertising but may not agree on whether to use television, radio, print, or social media because they lack knowledge about the relative effectiveness of these different media for their product. As a marketing manager once said, “I know that half my advertising expenditures have no effect on sales; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.”

In this case, managers often opt for an incremental approach, which could include making small changes or running pilot tests in various regional markets or with a small group of employees or customers. Continuous improvement refers to making many small, incremental improvements with regard to how things are done in an organization. Continuous improvement (often called kaizen) has been a pillar of success for companies like Toyota, where it helps members to be open to new ideas and to build high quality automobiles. This method works best in a stable environment, and over the course of time, even incremental changes can result in major change within an organization.[45] Finally, note that because decision-makers in this quadrant have little knowledge available, especially for non-incremental decisions, when making such decisions managers must be more open to speculation and guessing.[46]

Random (Low Agreement, Low Knowledge)

The random decision-making approach involves negotiations among decision-makers about which means and ends to pursue, and then making a choice even though decision-makers are unable to determine the costs and benefits associated with possible options. This is chaotic decision-making. Often decision-makers in this quadrant do not fully understand the problems and opportunities their organization is facing and thus simply choose to address the problem of the day with an idea they recently heard about. Choosing a solution (step 3) often precedes identifying the problem (step 1). In other words, decision-makers in this quadrant recognize a possible strength and implement it in the hope that it solves some problem. For example, a manufacturer that thinks 3D printers are the wave of the future might purchase several without knowing how they might be used. An accounting firm may recognize that it has several accountants skilled at auditing non-profit organizations, and so sets up a new department focused on non-profit auditing even though it currently has no non-profit clients.

Administrative Model (Medium Agreement and Knowledge)

Because managers usually have at least some knowledge and at least partial agreement on aims and means, they often use some aspects of all of the decision-making models mentioned so far. The administrative approach is characterized by satisficing, which is evident when decision-makers do not attempt to develop an optimal solution to a problem but rather collect enough information and develop enough alternatives until they feel they are able to choose one that provides an adequate solution. Satisficing is the result of bounded rationality, which explains that individuals make suboptimal decisions because they lack complete information and have limited abilities to process information (see Chapter 2).[47]

Satisficing means making adequate choices rather than the best ones possible, which suggests that this approach falls short of what constitutes optimal decision-making. However, satisficing also has a great and compelling strength: it reduces the time decision-makers must spend when they are developing and evaluating alternatives. Of course, there is still the challenge of stipulating what constitutes an “adequate” analysis and/or solution. If managers view satisficing as an interim solution rather than a cast-in-stone decision, if they are willing to learn from their mistakes, and if they are willing to undo former decisions based on what they have learned, satisficing contributes to an ongoing learning process. This brings us to final step in the decision-making process.

Test Your Knowledge

7.5. Step 4: Implement and Monitor the Choice

The fourth step involves implementing and monitoring the chosen alternative. After implementation, the four-phase cycle starts over again at the first step, as the outcome is monitored to see if it has solved the problem or perhaps unintentionally created a new problem. Managers face two key challenges in this step: (1) overcoming resistance to implementing a decision (i.e., resistance to change); and (2) overcoming resistance to recognizing and admitting decision mistakes. We will look at each in turn.

7.5.1. Overcoming Resistance to Implementing a Decision

Obviously, some decisions require more effort to implement than others. Generally, a routine programmed decision will be easier to implement than a non-programmed decision. For example, buying a new copying machine will be easier than acquiring another company. The most difficult decisions to implement are the ones that challenge an organization’s entrenched scripts and ways of operating. Even a technically brilliant decision will fail if it is not implemented in a way that members will embrace. Chapter 13 deals at length with the change implementation process, so at this point we will simply describe how the earlier steps in the decision-making process can be helpful in reducing resistance to change.

Perhaps the most fundamental way that managers can increase the likelihood that decisions will be implemented is to involve members in the decision-making process at the outset. Such involvement can be financially costly and is not necessary for many decisions, but it may be cost-effective and critical for some decisions.[48] A manager is encouraged to involve members in the decision-making process when the manager lacks information to make the decision, when members can be trusted because their goals align with the manager’s, when commitment from others is critical to success, and when there is ample time to make the decision.[49] FBL and TBL approaches are inclined to limit employee participation in order to reduce financial costs,[50] but they encourage participative decision-making when it serves the organization’s financial interests.[51] SET managers are more likely to welcome participative decision-making because they recognize its inherent value in involving others and thereby increasing social well-being. As a result, SET managers are likely to meet less resistance during step 4 and are more likely to respect any resistance they do experience.[52]

Managers must not naively assume that participation will always lead to unanimity. The fact is that there will often be people who would rather not implement a particular decision. One way to deal with this reality is to make implementation invitational rather than required. SET managers may allow members who oppose a decision to not implement it. For example, when Robert Greenleaf made managers at AT&T aware of the problem of low promotion rates for African American employees (step 1 of the decision-making process), a number of alternatives were developed (step 2), and two were chosen for implementation (step 3) on an invitational and experimental basis (step 4). In the first experiment, Greenleaf worked with those who were agreeable to deliberately recruiting African American employees for AT&T management training programs. The second experiment involved offering African American technical specialists a broader range of job experiences in order to better prepare them for managerial positions. Initially some managers opted out of both experiments, but over time these became the new normal scripts and eventually helped to increase the proportion of African American managers at AT&T almost tenfold (addressing issues in step 1).[53]

7.5.2. Overcoming Resistance to Recognizing a Mistake

Once a decision has been implemented, the decision-making process goes back again to step 1, where managers monitor its outcomes. If a decision has resolved the original issue, managers can continue to support the decision. However, research suggests that about half of all non-routine decisions fail.[54] In such cases, where the decision has failed to resolve a problem or may have created unanticipated additional problems, the key for managers is to learn from their mistakes and to transform them into knowledge-creating events that can be used in future decision-making processes. As the great inventor Thomas Edison put it: “I have not failed. I have just found ten thousand ways that won’t work.”[55] In fact, CEOs from corporations like Netflix, Amazon, and Coca-Cola have worried when their firms’ new projects do not fail often enough, suggesting that it means they’re not bold enough and not getting enough chances to learn from their failures.[56]

Unfortunately, many poor decisions persist for longer than they should because managers are reluctant to admit that they made a mistake. This persistence leads to escalation of commitment, which occurs when a manager perseveres with implementing a poor decision in spite of evidence that it is not working. Figure 7.5 shows three specific reasons why escalation of commitment occurs, but the most fundamental reason is that managers refuse to admit that they made a poor decision. First, escalation of commitment often occurs in tandem with information distortion, which refers to the tendency to overlook or downplay feedback that makes a decision look bad and instead focus on feedback that makes the decision look good. For example, one study found that despite rising mortality rates in the pediatric cardiac surgery program at Bristol Royal Infirmary in England, key decision-makers in the hospital (in particular, the CEO and surgeons) chose to ignore indicators of poor performance and negative feedback, and instead developed norms and routines that limited the likelihood they would abandon their bad decisions and learn from their failing practices (see also Chapter 17 on managers’ reluctance to accept feedback).[57]

Figure 7.5. Factors that contribute to escalation of commitment

Second, escalation of commitment can also be caused by too much persistence, which refers to remaining committed to a course of action despite obstacles. Persistence can be expressed as “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” When asked about the key secret to his success, Facebook CEO and co-founder Mark Zuckerberg said: “Don’t give up.”[58] This tendency is reinforced by stories about managers who refused to admit failure despite early negative feedback and were subsequently treated as heroes when their decision turned out to be right. For example, an engineer named Chuck House at Hewlett-Packard received a “Medal of Defiance” because even though Dave Packard himself had told him to quit working on a particular project, he persisted in using organizational resources to develop what eventually became a highly successful new product.[59] In this case, not listening to the boss garnered a positive response, but in many other cases it will garner a certificate of a different sort (i.e., a “pink slip” indicating termination of employment). The challenge of knowing when to persist and when to abandon and learn from a mistaken decision is especially relevant for entrepreneurs operating in a context with a high level of uncertainty. For example, there have been many occasions where software game developers invested too many resources into games that were never released.[60]

Third, escalation of commitment can also occur because of administrative inertia. Administrative inertia happens when existing structures and systems persist simply because they are already in place. Administrative inertia is related to the concept of sunk costs, which suggests that once investments have been made in a project, managers are more likely to persist with that project even when it is not going well. Inertia is a particularly salient for the decision-makers who made the decision in the first place. If millions of dollars have been spent on a merger that is of questionable value, once that merger has become part of the organization’s new structure, managers will be reluctant to undo that decision even though it has led to poor organizational performance.[61]

What can be done to reduce the likelihood that escalation of commitment will occur? One option is to make decisions in groups rather than give decision-making responsibility to a specific manager, because groups may feel less threatened when admitting a decision mistake.[62] Another tactic is to set specific criteria or performance milestones when the decision is made regarding what will constitute unacceptable performance outcomes. Software game developer Steve Fawkner describes how even though a project was failing to meet milestone performance targets, his company persisted in working on the project for an additional six months, by which time “our studio had been ruined, and we were down to three employees.”[63]

Rather than view decisions as a legacy to be maintained, managers should ask themselves what they have learned from their decisions that can improve future decisions. In particular, managers must be bold enough to take what they have learned and undo poor decisions. Recognizing a previous faulty decision is often easier for new managers than for the managers who originally made the poor decision. For example, new managers are 100 times more likely to sell a business unit that was acquired as a result of a poor decision than the managers who made the acquisition decision in the first place.[64]

Managers who regularly challenge the status quo, as SET managers may be more likely to do than FBL and TBL managers, may find it easier to avoid escalation of commitment because they are more likely to see decisions as “experiments” that can be improved via subsequent feedback and participation. More generally, managers who are predisposed to improving decisions for the overall good rather than defending their own narrow agendas or values are more likely to be open to change.[65] This reduces the likelihood of escalation of commitment, information distortion, inappropriate persistence, and administrative inertia. It also increases the likelihood that managers will learn from poor decisions.

Test Your Knowledge

7.6. Entrepreneurial Implications

The four-step decision-making process is particularly helpful for entrepreneurs, because they make a high proportion of non-programmed decisions when they start a new venture. Of the many decisions classic entrepreneurs make, among the most important are “make-or-buy” decisions. In essence, entrepreneurs need to decide what sorts of goods and services to make within their start-up, and which goods and services they can buy as inputs from suppliers. The Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company, which is owned and operated in Winnipeg, Canada, by Tabitha Langel and several others, offers a good example of how the four-step decision-making process can be used to determine whether to make or buy.[66]

Tall Grass was started in the early 1990s, when Langel and her friends identified a significant problem and recognized an opportunity it presented—the first step in the decision-making process. Small-scale local farmers were suffering financially, and even dying of suicide, owing to a lack of opportunities to sell their grains at viable prices. Moreover, they realized that there was nowhere in their city where people could purchase wholesome, fresh-baked bread made from local organic ingredients. The founders believed that it was important to make such bread available for others to buy, because this would support local farmers, take better care of ecological resources (e.g., soil), and foster community.

This problem, opportunity, and belief led to the second step, which was to consider the various make-or-buy alternatives for starting such a bakery. For example, should the bakery buy its building and equipment, or lease it? Should it bake bread and have a storefront selling directly to customers, or should it sell bread through grocery stores? Should the bakery hire its own accounting or marketing personnel, or should it outsource those tasks? An especially important matter was how to turn local organic wheat into flour. Should the bakery ask farmers to do this, contract with a flour mill to do this, or purchase a flour mill and do this in-house at the bakery?

For the third step of the decision-making process—choosing an alternative—it is helpful to draw from transaction cost theory to help understand and inform make-or-buy decisions.[67] Transaction costs are expenses that do not contribute directly to producing an organizational output but exist only to reduce threats from opportunism and uncertainty. Transaction cost theory suggests that in a perfect world, “buying” is usually better than “making.” In our example, it is more efficient for one organization (a farm) to grow organic wheat, for another organization (a flour mill) to turn the wheat into flour, and for another (a bakery) to turn the organic flour into bread.

However, transaction cost theory notes that the world is often imperfect for two reasons: people are opportunistic, and they have limited cognitive capacity. First, people sometimes behave opportunistically, meaning that they cheat or mislead others to achieve their own self-interests. Because we can’t trust everyone all the time, we must develop safeguards to ensure that people keep their part of an exchange. For example, a farmer may be tempted to sell regular grain at a premium price, claiming it has been organically grown, or perhaps a flour mill will be tempted to take regular flour and sell it at a higher price, claiming it is made from organic wheat.[68] One way to deal with this is to hire a third party to inspect and certify the flour or flour mill. Another way is for a bakery to ensure that it has the organic wheat it requires by growing its own wheat and purchasing its own mill.

Second, transaction cost theory suggests that the make-or-buy decision is informed by people’s limited cognitive capacity, which creates uncertainty when buying needed items. Entrepreneurs can’t think of all the possible things that might go wrong and add them into a contract when purchasing supplies. At a more basic level, will the farmer supplier know how to grow organic wheat, especially in unexpected weather conditions? Will the mill have enough flour on hand at the predetermined price when the bakery wants to buy it?

Safeguarding against opportunism and uncertainties can take a variety of forms, such as writing contracts that address as many uncertainties as possible, implementing monitoring systems, or conducting quality tests and spot checks. Doing any of these things takes time and incurs transaction costs. For example, a baker who is worried about being sold low-quality flour may pay to have an independent third party to certify the flour and its production. This expense won’t contribute directly to the quality of baked goods, but is an additional cost that must be incurred to ensure high quality. The higher the transaction costs, the more likely a bakery will be to make rather than buy its flour.

From a transaction cost theory perspective, the best make-or-buy choice is the one that is the most financially efficient. Although typically it is more efficient for a bakery to buy its ingredients, this may not be the case for a specialty product like local organic flour, where it may be more economical for a bakery to mill its own. Milling its own flour also incurs extra costs for the bakery beyond simply milling flour, such as the cost of buying and servicing a flour mill, hiring and monitoring a part-time mill operator, paying employee benefits, and so on. But if these costs are lower than the costs and uncertainty associated with buying organic flour, then it is better for the bakery to process its own flour.

In the case of Tall Grass, once it had established that there were customers who wanted to buy its organic bread, it made an agreement with a local farmer to grow and supply organic wheat and bought its own small (about 2-horsepower) flour mill to make its own organic flour in the bakery. Even if it had been able to purchase imported organic flour for a lower financial cost, having a local supplier was important to the bakery’s overall vision of promoting socio-ecological well-being.

The fourth step in the decision-making process is to implement and monitor the decision. As it happened, the make-or-buy decisions that Tall Grass made worked out very well.[69] In particular, having farmers come to the bakery to deliver their grain was an opportunity to build community (which is priceless):

The first time that [a particular farmer] brought in a shipment of grain and I was baking, I introduced him. There were about 5 or 6 customers, so I introduced them. And he was a big burly farmer. Everybody spontaneously just started cheering. And he just started crying. He said, “I always feel so unwelcome in the city, because it’s not for us. It’s the first time I’ve ever experienced [this feeling].” (Tabitha Langel, owner)[70]

In more instrumental terms, there was a marketing benefit for customers to be able to meet the farmers who grew the wheat, and this interpersonal relationship increased trust and reduced the likelihood of opportunism. Another marketing benefit was that the bakery came to be known as operating the largest commercial flour mill in its region.[71] However, as the larger market for organic flour grew, more suppliers entered the market, and Tall Grass eventually decided to buy organic flour from suppliers.

All organizations need to make similar decisions about whether to make or to buy the inputs that they need. These make-or-buy decisions are an important source of entrepreneurial opportunities, because when a large firm decides to outsource work, that decision creates a need that an entrepreneur may fill. Many firms outsource services such as payroll and health benefits, leading to a demand that another organization can satisfy (see Boldr, opening case in Chapter 5). All business-to-business entrepreneurs are trying to gain from another organization’s decision to buy rather than make some good or service.

Finally, transaction cost theory not only offers entrepreneurs guidance in making decisions about which inputs to make or buy (e.g., by calculating transaction costs) but also offers insight in terms of outputs. On the output side, the entrepreneur should think about the transaction problem from the perspective of the customer. The new organization should be created to offer goods and services that enable customers to minimize their transaction costs. In the case of Tall Grass, having generous return policies for their products can reduce customer uncertainty about buying their bread. Both establishing personal relationships and offering transparency in operations help to reduce the customer’s worry about opportunism. The staff at Tall Grass are known for their friendliness, and customers at the counter are able to see the ovens and other equipment being used by the bakers.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- FBL, TBL, and SET managers follow the same basic four-step decision-making process, but the process unfolds differently based on general scripts used in each approach.

- The first step is to identify the need for a decision (e.g., by noting a problem that needs to be solved or an opportunity that can be seized).

FBL managers tend to place the highest attention on problems and opportunities that can maximize the organization’s financial well-being, and pay relatively little attention to socio-ecological externalities and external stakeholders.

TBL managers also focus on problems and opportunities that can maximize the organization’s financial well-being, but are more likely to enhance profits by reducing negative socio-ecological externalities and attending to external stakeholders.

SET managers place the least attention on maximizing the organization’s financial well-being, and focus most on reducing negative and enhancing positive socio-ecological externalities and attending to external stakeholders.

- The second step is to consider alternative responses to choose from (do nothing, programmed response, or non-programmed response).

FBL managers are most likely to “do nothing” (since they face fewer socio-ecological prompts to make decisions), while SET managers may be most likely to develop non-programmed responses (since programmed SET practices are relatively new to management). The responses of TBL managers will fall somewhere between those of FBL and SET managers.

- The third step is to choose the appropriate alternative (influenced by the level of agreement on aims and means, and by the amount of relevant knowledge available to decision-makers).

FBL managers are the most likely to expect agreement on aims and means, the least likely to focus on socio-ecological risk and uncertainty, and the most reluctant to rely on tacit knowledge. SET managers are least likely to expect agreement on aims and means, most likely to focus on socio-ecological risk and uncertainty, and most open to tacit knowledge. The responses of TBL managers will fall between FBL and SET managers.

- The fourth step involves implementing and monitoring the chosen alternative.

FBL managers may be the least inclined to use participative decision-making processes and therefore less likely to learn from decision mistakes. SET managers are most inclined to use participative decision-making processes and most open to learning from decision mistakes. The actions of TBL managers will fall between FBL and SET managers.

- When entrepreneurs consider make-or-buy decisions, they should seek to reduce opportunism and overcome shortcomings associated with cognitive limits.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Identify and briefly describe each of the four steps of the decision-making process.

- Which of the four steps do you think is the most challenging for managers? Why do you think so?

- Which of the decision-making approaches in Figure 7.2 would you find most helpful? Why?

- How important are workplace politics in organizations? Explain how politics influences management decision-making. What is the best way to deal with politics?

- Based on the content of this chapter, what advice might you have for colleagues in your class to help them avoid what happened to Dennis Gioia in the opening case?

- Explain how you made the decision regarding which post-secondary school to attend or which major to study. Did your decision-making process follow the four-step process described in the chapter? Which steps were most important in your decision? Why?

- Think about a good or service that many organizations are currently making in-house but which they might prefer to buy from a supplier. Can you think of an entrepreneurial start-up that could offer that good or service at a low enough cost to entice those organizations to outsource from it?

- This case is drawn from the following sources: Gioia, D. (1992). Pinto fires and personal ethics: A script analysis of missed opportunities. Journal of Business Ethics, 11: 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00870550; Davis, R. (2017, January 18). When lives are cheaper than financial losses: Ford Pinto’s chilling lesson. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-01-18-when-lives-are-cheaper-than-financial-losses-ford-pintos-chilling-lesson/#.Wm9SXGYZNBw; Nutt, P. C. (2002). Why decisions fail: Avoiding blunders and traps that lead to debacles. Berret-Kohler Publishers; Birsch, D., & Fielder, J. H. (Eds.). (1994). The Ford Pinto case: A study in applied ethics, business, and technology. State University of New York Press; Ming, X., Bai, X., Fu, J., & Yang, J. (2025). Decreasing workplace unethical behavior through mindfulness: A study based on the dual-system theory of ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 196(1): 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05709-9 ↵

- Note that the scripts at Ford may have been influenced by a court decision in 1919 that ruled against Henry Ford’s intent at the time to improve the lives of employees and society by increasing wages and creating jobs, because this subordinated the financial interests of stakeholders See Giroux, G. (2017). Accounting fraud: Maneuvering and manipulation, past and present (2nd ed.). Business Expert Press. ↵

- This amount was eventually reduced to .5 million by the judge. Needless to say, this new knowledge about the financial costs of not recalling the car subsequently served to change Ford’s decision calculus, and in 1978 Ford upgraded the integrity of Pinto’s fuel system. It stopped producing the Pinto in 1980. Some observers view this incident as the beginning of a new emphasis on making managers more accountable for socio-ecological externalities of their decisions. ↵

- Gioia (1992: 379). ↵

- Gioia (1992: 379–380). ↵

- Gioia served as Ford’s recall coordinator from 1973 to 1975. When he started in 1973, he inherited the oversight of about 100 active recall campaigns and had additional files of incoming safety problems, one of which included reports of Pintos “lighting up.” Important stories in the public media on Pinto problems were published in 1976 and 1977. After three teenage girls died in a Pinto fire, a grand jury took the unprecedented step of indicting Ford on charges of reckless homicide (Gioia, 1992). ↵

- The Pinto case was one of the files on Gioia’s desk, and though he was no longer the recall coordinator in 1978, had he acted earlier and ordered a recall, the future damage could have been avoided. ↵

- Gioia (1992: 382). ↵

- Gioia (1992: 384). ↵

- Ming et al. (2025). ↵

- Recall from Chapter 2 that scripts are learned guidelines or procedures that help people interpret and respond to what is happening around them. See also idea of “cognitive scripts” in Eikeland, T. B., & Saevi, T. (2017). Beyond rational order: Shifting the meaning of trust in organizational research. Human Studies, 40(4): 603–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-017-9428-6; and “action scripts” in Calabretta, G., Gemser, G., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2017). The interplay between intuition and rationality in strategic decision-making: A paradox perspective. Organization Studies, 38(3–4): 365–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616655483; Dyck, B. (1991). Prescription, description and inscription: A script theoretic leadership model [Presentation]. Organization and Management Theory Interest Group, Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Niagara Falls, Ontario. ↵

- Dyck, B., & Weber, M. (2006). Conventional versus radical moral agents: An exploratory look at Weber’s moral-points-of-view and virtues. Organization Studies, 27(3): 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606062430 ↵

- Turzo, T., Montrone, A., & Chirieleison, C. (2024). Social accountability 8000: A quarter century review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 441: 140960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140960 ↵

- Reid, H., & Pons, C. (2023, July 27). Zara owner Inditex says it will stop buying clothes from Myanmar. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/zara-owner-inditex-stop-sourcing-myanmar-2023-07-27/ ↵

- The ongoing example of Robert Greenleaf in this chapter builds on material found in Nielsen, R. P. (1998). Quaker foundations for Greenleaf’s servant-leadership and “friendly disentangling” method. In L. C. Spears (Ed.), Insights on Leadership (pp. 126–144). John Wiley & Sons. Greenleaf joined AT&T in 1929 as a laborer’s assistant and retired in 1964 after having served as corporate human resources vice president and as director of management development and research. Greenleaf was inspired by John Woolman, who had been similarly motivated by larger issues of social justice when he invested time and money into abolishing slavery in the United States. ↵

- For example, see Jo, H., & Na, H. (2012). Does CSR reduce firm risk? Evidence from controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(4): 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1492-2 ↵

- Dawes, R. (1988). Rational choice in an uncertain world.: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ↵

- And these norms will change as new cohorts of employees enter the workforce. Janssen, D., & Carradini, S. (2021). Generation Z workplace communication habits and expectations. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 64(2): 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2021.3069288 ↵

- Winnipeg coffee shop responds to break-in by donating part of sales to homeless shelter (2018, February 2). CBC News Manitoba. http://www.cbc.ca/beta/news/canada/manitoba/parlour-coffee-break-in-main-street-project-1.4515471 ↵

- Bruch, E., & Feinberg, F. (2017). Decision-making processes in social contexts. Annual Review of Sociology, 43: 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053622. What we describe here as a dilemma, Bruch & Feinberg call “obscurity.” ↵

- Our definitions of risk and uncertainty build from the following: Shou, Y., & Olney, J. (2021). Attitudes toward risk and uncertainty: The role of subjective knowledge and affect. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 34(3): 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2217; Bruch & Feinberg (2017); Burns, B. L., Barney, J. B., Angus, R. W., & Herrick, H. N. (2016). Enrolling stakeholders under conditions of risk and uncertainty. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(1): 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1209; Merigó, J. M. (2015). Decision-making under risk and uncertainty and its application in strategic management. Journal of Business Economics & Management, 16(1): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.3846/16111699.2012.661758; Scholten, K., & Fynes, B. (2017). Risk and uncertainty management for sustainable supply chains. In Y. Bouchery, C. J. Corbett, J. C. Fransoo, T. Tan (Eds.), Sustainable supply chains (pp. 413–436). Springer International. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29791-0_19. Our definitions are not entirely consistent with the classic distinction between risk and uncertainty associated with the economist Frank Knight; see Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty, and profit. Hart, Schaffner & Marx, Houghton Mifflin. ↵

- Burns et al. (2016). ↵

- Wallace, D. (1975). Naming the Edsel. Automobile Quarterly, 13(2): 182–191. Cited in Schwarzkopf, S. (2015, July). Data overflow and sacred ignorance: An agnotological account of organizing in the market and consumer research industry [Presentation]. EGOS Conference, Athens. http://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4694.3849 ↵

- According to analysis in Schwarzkopf (2015). ↵

- Varsha, P. S. (2023). How can we manage biases in artificial intelligence systems—A systematic literature review. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 3(1): 100165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2023.100165; Lytton, C. (2024, February 16). AI hiring tools may be filtering out the best job applicants. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20240214-ai-recruiting-hiring-software-bias-discrimination ↵

- IBM Data and AI Team. (2023, October 16). Shedding light on AI bias with real world examples. IBM. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/shedding-light-on-ai-bias-with-real-world-examples ↵

- Miller, C. C., & Ireland, R. D. (2005). Intuition in strategic decision-making: Friend or foe in the fast-paced 21st century? Academy of Management Perspectives (was Academy of Management Executive), 19(1): 19–30. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.15841948. One researcher asked managers to guess random ten-digit computer-generated numbers, and found that successful businesspeople were significantly better at guessing the numbers than those with average ability in the business world. Dean, E. D., Mihalasky, J., Ostrander, S., & Schroeder, L. (1974). Executive ESP. Prentice-Hall. ↵

- In Chapter 8, we will look more closely at how goals are set, but for now we will concentrate on whether or not there is agreement on aims and means. ↵

- Hall, R. I. (1976). A system pathology of an organization: The rise and fall of the old Saturday Evening Post. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(2): 185–211. http://doi.org/10.2307/2392042 ↵