Part 4: Leading

16. Groups and Teams

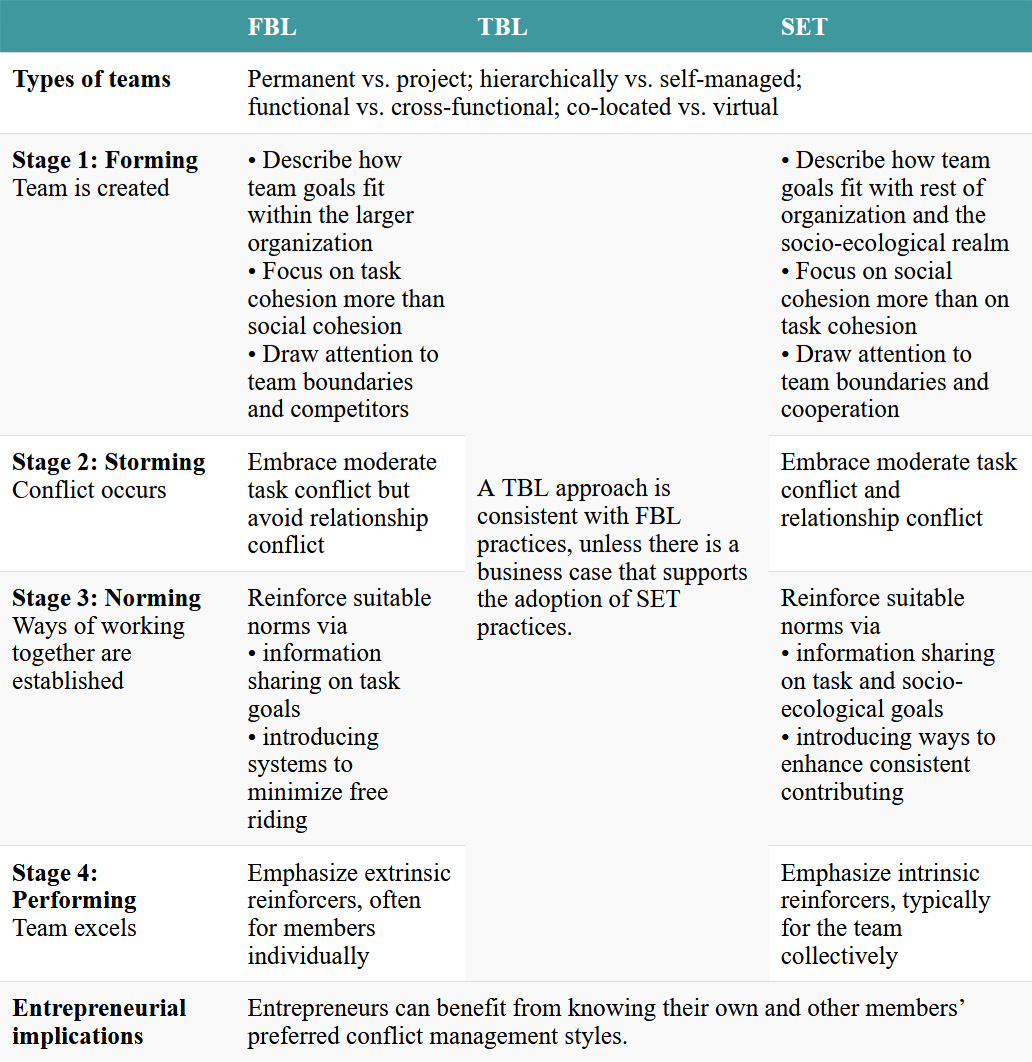

Chapter 16 introduces different kinds of groups and teams, and then describes the four stages of team development: forming, storming, norming and performing, as described in the table below and on the chapter whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain differences between groups and teams.

- Identify four different dimensions along which teams can vary.

- Describe the essential features of the four stages of team development.

- Understand how the development of social and task cohesion proceeds in each of the four stages of team development.

- Describe key leadership behaviors in each of the four stages of team development.

- Explain the differences in how teams are managed under FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

- Describe different conflict management styles, and how entrepreneurs can benefit from learning about their own and other members’ preferred style.

16.0. Opening Case: Lifelong Lessons in Teamwork

When it comes to experiencing social well-being within an organization, there may be nothing quite so rewarding as being a member of an effective team. Teams are small enough to facilitate meaningful interpersonal relationships and large enough to provide opportunities to make valuable contributions to completing tasks that individuals could not achieve independently. Indeed, when students are asked to identify where they feel most connected to others, they mention sports teams about as often as family.[1] They also mention working at summer camps for children and youth.[2]

Kate Cassidy had a life-changing experience working as part of the team of counselors at a small camp in Quebec, Canada: “It had a profound effect on my goals, choice of career, and who I have become.”[3] Summer camps are typically organized around a variety of teams, including a team that maintains the physical facilities of a camp (e.g., ensuring that the lawn is mowed), a team to work in the kitchen, a leadership team in charge of programming (overseeing camper activities), a team of support staff (e.g., lifeguard, canoe instructor), and a team of counselors who work directly with the campers.

When Cassidy describes her experience of working at camp, you can see several stages of team development. First, when she started and the counselor team was being formed, she was on her best behavior, trying to be accepted as she learned more about the group and what her job would entail:

I arrived that summer thinking I had to act in a certain way to fit in. I admired the staff who were funny and outgoing, and thought their behavior defined the ideal camp staff member. I did my best to act accordingly, but it proved difficult to maintain 24 hours a day.

Because of this, Cassidy considered quitting her job, but first she decided to quit trying to be what she thought her teammates expected of her and instead began to be her authentic self (i.e., more serious and inward-looking). To her surprise, she was still fully accepted by her teammates:

I remember that a feeling of acceptance for being myself was different from the more limited sense of belonging I felt when I knew I was not being authentic. It was great to feel fully accepted, and perhaps this struck me so forcefully because I do not believe I had experienced this sense before outside my family. This was my first experience of fully “being” in community.

Of course, not everything is sunshine and roses, even at summer camp. It was inevitable that conflict would occur among a group of people working together all summer, twenty-four hours a day. Although Cassidy had grown up thinking that conflict was a bad thing, she learned to understand its positive aspects through her camp experience:

I came to realize that conflicts were almost always talked through respectfully, and resolved. I saw this done regularly, even facilitated the process with campers, and usually saw both parties emerge with tighter bonds and a better understanding of each other. Camp changed my idea that conflict was always a negative thing that should be avoided. I learned that when it happened in an atmosphere of care and respect, and people were open to talking about it, new insights and a deeper connection could result.

As a community of around seventy people, it was important to develop and re-develop agreed-upon guidelines for behavior:

Our camp community was guided by norms of care and respect. . . . It was generally understood that breaking those rules could have a negative effect on others. There were times that rules were broken, and the reasoning and consequences were always discussed. To some extent, the rules were also open to negotiation as well. . . . We all cared for each other and we used this as guidance to follow or change rules and to make decisions.

Having time and space for meaningful dialogues was particularly important:

Sharing fears, wondering about deeper meanings, and exploring different perspectives were all commonplace. I think this helped us come to appreciate the fact that although camp members looked different on the surface (different religious, economic, and language backgrounds),[4] everyone had commonalities and differences that ran deeper, and we were more unique than these surface categories. For people to feel they can be themselves, they must first know that the time and space is there for them to be deeply heard.

Cassidy and the rest of her team performed very well as a cooperative community.

We knew each other’s strengths and weaknesses and accepted them non-judgmentally. Whenever anyone needed help or support, it was there for them. . . . We experienced challenges, disappointments, and arguments, but the care for each other was always there and from every struggle, people seemed to emerge stronger. It was a perfect social atmosphere for campers and staff alike to take risks, try new things, develop new skills, and learn more about ourselves.

Her positive experience as part of the team at camp has shaped her subsequent professional choices, her management style, and her friendships decades years later:

It has been almost 25 years since that summer but the bonds we created were very strong and many of the staff and campers are still friends today.

16.1. Introduction

In addition to being parts of functional or divisional departments (see Chapter 11), organizational members are often divided into teams. If properly managed, teams can enhance social well-being and meaningful work, improve the quality of decision-making, heighten creativity, increase motivation, and help facilitate organizational change. Teams also can allow managers to decrease their direct supervision of employees by reassigning some supervisory duties to team members.[5] Teams can help organizations encourage high-involvement work cultures and flatter and more flexible organizational structures that adapt to changes in technology.[6] However, poorly managed teams may lead to dysfunctional conflict that decreases job satisfaction, increases turnover and absenteeism, and reduces the overall performance of team members and the organization. Thus, managers must understand and manage team processes effectively so they can take advantage of their positive aspects and avoid the negative.

We begin this chapter by differentiating between groups and teams, and then describing different types of teams. The bulk of the chapter describes how teams develop over time and identifies the key processes that are typically evident at each stage of team development. As with other chapters, we will highlight the similarities and differences between Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) approaches to teams.

16.2. Groups, Teams, and Different Types of Teams

16.2.1. Groups Versus Teams

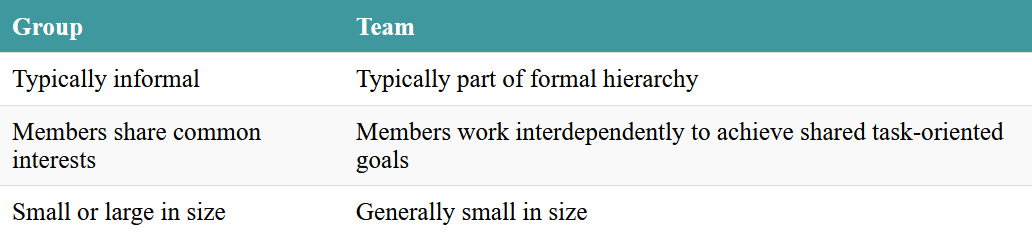

Often the terms “group” and “team” are used interchangeably, which in many cases may be appropriate. Both terms can refer to collectives of three or more members within an organization. However, there are significant differences between the two. A group is a collection of three or more people who share a common interest or association. Examples include a work-based book club, co-workers who regularly play cards over lunch, and co-workers who exercise together in the company gym. A team is a collection of three or more people who share task-oriented goals, work toward those goals interdependently, and are accountable to one another to achieve those goals. Examples include work teams within a department, a bargaining team within a labor union, and the top management team in a new start-up organization. Table 16.1 summarizes some of the characteristics that differentiate groups and teams.

Table 16.1. Typical characteristics of groups and teams

Groups are typically informal, such as organizational members who eat lunch together regularly at the same table in the company cafeteria. In contrast, teams are typically formally constituted—members are assigned to a team by managers—but teams can also have informal qualities as members befriend each other when they work together.

Groups are typically more concerned with a common interest and with the benefits of the interpersonal relationships associated with membership. In contrast, teams are created with task achievement goals in mind, though members may share common interests and enjoy social relationships with their team members. Team members are more likely to need to rely on the work of other members to successfully complete tasks, whereas group members may work independently from one another.

Groups can range in size from a few people to thousands. Generally, teams are smaller in size due to limitations in how many people can work together interdependently; however, larger teams may be possible if work is divided into sub-teams.[7] For example, an American football team may include three sub-teams (offense, defense, and special teams), each of which may be further divided into sub-teams (e.g., offensive line, backs, and receivers).

Unless otherwise noted, we will focus primarily on teams in the rest of this chapter, in part because it’s relatively easy to define membership, and in part because managers of organizations are more likely to be interested in work teams given their task and goal orientation.

16.2.2. Types of Teams

There are many types of teams, and they are configured in many different ways. Members may work together for a short time, or the arrangement may be relatively permanent. A team may have a direct manager, or members may manage themselves. A team may be composed of people from the same function, or include members from multiple functions. Members may work side by side, or live and work in geographically diverse settings. And of course, teams will be some combination of all these different categories. Some common types of teams are described below.

Permanent Versus Project Teams

Teams can be relatively stable and ongoing (permanent), or their existence may be relatively fleeting, to meet short-term needs (project). One kind of project team is a task force that has been set up to accomplish specific goals or to solve a particular problem, and which disbands once it completes its task. Such task forces are becoming more important as organizations need to deal with increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous information.[8] For example, Robert Greenleaf essentially invited interested managers to participate on a task force to increase gender hiring equity at AT&T (Chapter 13). Project teams are different from permanent teams in that project teams have a predefined and limited life and role to serve in the organization.

Hierarchically Versus Self-Managed Teams

In traditional hierarchically managed teams, a leader is given the responsibility and legitimate authority to manage the team. The formal leader sets the agendas, assigns the tasks, and ensures that each member is performing their job. In recent years there has been a steady increase in the use of self-managed work teams.[9] A self-managed work team typically consists of members who are given primary responsibility to manage themselves on a daily basis.[10] These responsibilities may include scheduling, rotating jobs, making work assignments, hiring new team members, and deciding on who will take the lead in different aspects of the team’s activities. Members of self-managed teams tend to get satisfaction from their increased discretion in decision-making,[11] though being part of a self-managed team can also be experienced as tyrannical when it is based on an instrumental ideology that subverts alternative views.[12] Self-managed teams tend to be very cost effective and reduce the need for many levels of management. At Johnsonville Foods, for example, self-managed teams have the authority to recruit, hire, evaluate, and fire team members on their own. Team members train one another, track their own budgets, make capital investment proposals, and handle quality control inspections.[13]

Functional Versus Cross-Functional Teams

A functional team has members who work in the same functional department or area, such as marketing or finance. Because members do not come from a variety of areas, there is greater homogeneity among them and a greater likelihood of getting along socially as a group. Functional teams are formed to achieve functional-level goals, such as efficient production lines and trustworthy and affordable suppliers. Cross-functional teams bring together people who have a variety of expertise and knowledge from different organizational functions (akin to divisional departmentalization). They are assembled to achieve organizational-level goals or goals that require cooperation across functions. Overall, research suggests that diversity among team members helps to enhance creativity and satisfaction, but it also increases task conflict and reduces social integration (see also Chapter 10 on functional versus divisional departmentalization).[14]

Co-located Versus Virtual Teams

Co-located team members see each other regularly, often many times a day. They share the same office space or work on the same assembly line, and have plenty of opportunities to develop relationships with one another. A virtual team is composed of members who live in geographically diverse settings. Members rarely if ever meet face to face; instead they interact via email, phone, and video-conferencing. Virtual teams have grown in popularity because (a) organizations have become increasingly global, (b) recent technological advances have made virtual teams feasible, (c) there is increasing need for highly specialized workers who can work in innovative and flexible situations, and (d) after COVID-19 many people prefer to work from home if they can.[15] For example, the design of an automobile may include team members who span several continents and time zones. Designers in California work an eight-hour shift designing the car, then pass it electronically to team members in India who work on it for another eight-hour shift, who then send it to team members in the UK to work on for eight hours, who finally send it back to California for the next shift cycle. A virtual team may also involve members who are from various other organizations, such as when a textbook is written by co-authors who never or rarely meet face to face.

16.2.3. FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Teams

All three management approaches encourage the use of teams, but for different reasons. Even though teams seem to go against the idea of individualism, the FBL approach recognizes that teams can help to improve productivity and profits. In contrast, while a SET approach welcomes such improved financial outcomes, it values teams because they also enhance community and overall well-being (recall from Chapter 1 that from a virtue ethics perspective, human flourishing is optimized when virtues are practiced in community rather than individually).

Test Your Knowledge

16.3. Stages of Team Development

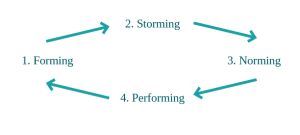

While no two teams are the same, and there is always variation in how teams develop over time, research suggests that it is helpful to think about teams going through a series of four developmental stages.[16] As shown in Figure 16.1, the four stages are called forming, storming, norming, and performing. A fifth stage, adjourning, applies to some teams and we will briefly discuss it separately near the end of the chapter.

Figure 16.1. The four-phase model of team development

In reality, the team development process can be an ongoing process that is much messier than implied by Figure 16.1. For example, while “forming” may be especially important in the early stages of a team’s life cycle, team members must engage in ongoing “re-forming” activities as new members join and when the parameters of the team’s responsibilities change.

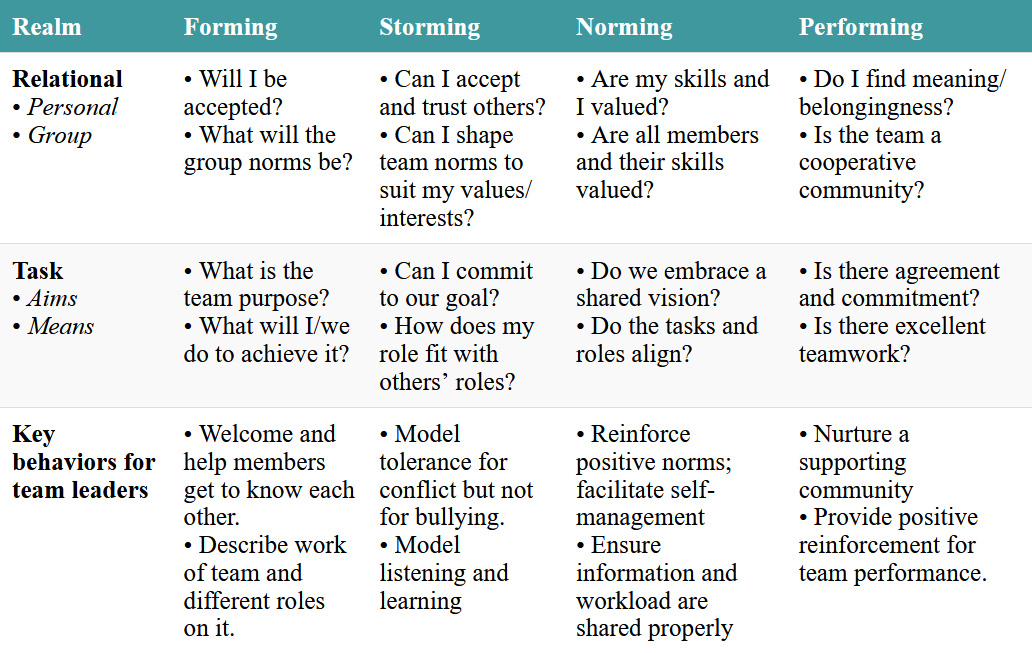

Table 16.2 provides more detail about what happens at each stage of team development, showing how each stage requires team members to address relationship-oriented issues (both at a personal and a group level) and task-oriented issues (in terms of both aims and means).[17] By understanding these relationship- and task-oriented issues and responding appropriately, team leaders can help to facilitate team development and improve team performance.[18] We will discuss each stage in turn.

Table 16.2. Stages of team development

16.3.1. Stage 1: Forming

The first stage refers to the start of a new team, but many aspects of this stage will also be relevant when new members join an existing team. We will discuss each of the aspects listed in Table 16.2

Relationship-Oriented Issues in Forming

The key part of this stage is to help individuals answer a variety of questions they bring with them whenever they join a new team, including overarching questions such as “Will I be accepted?” and “Will the team be successful?” Members typically experience anticipation and excitement alongside apprehension and uncertainty when joining a new team. Overt disagreement among team members is typically low in this stage because members are focused on making a good first impression. New teams must begin the work of developing a group identity as they develop norms about how they will interact with each other; this work continues throughout the four stages of group development and is a focal point of stage 3, norming.

Task-Oriented Issues in Forming

Another important element of this stage is for members to learn the basic purpose of the team (aims) and how the team members will fulfill its purpose (means). Part of this includes identifying the team’s task boundaries, which involves letting members know what the team is and is not responsible for doing. For example, one team might be responsible for developing new products and services for an organization, while a different team is responsible for testing the marketability of those products. Identifying the boundaries of a team’s tasks is important for helping members understand what their responsibilities are. This is also the time when members begin to think about and clarify the various responsibilities and roles each member will have in achieving the team’s goals. Roles such as project manager, analyst, spokesperson, and so on describe the various positions and activities members will perform in helping the team achieve its goals.[19]

Relationship-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Forming

In order to address the relevant relationship-oriented issues in the forming stage, leaders need to make members feel welcome and to start the ongoing work of developing social cohesion (which is necessary in all the stages).[20] Social cohesion is the attachment and attraction of team members to one another. Typically, social cohesion increases along with similarities among group members, time spent together, shared positive experiences, and shared goals.[21] Social cohesiveness is fostered when members learn to trust one another. This mutual trust takes time to develop, but managers can hasten trust-building by modeling trustworthiness in their relationships and by facilitating open communication among members. For example, they could start meetings with “warm-up” questions like “If you had the day off today, what would you do?” Learning about the interests of other team members helps to develop a fuller understanding of them and enhances relationships. Managers can also encourage social interaction by hosting a lunch or working on group-building exercises. As a more extreme example, some start-up companies have used an exercise that challenges team members to survive in a forest, believing that this will provide a common bonding experience and help members learn to collaborate. However, it has been noted that such exercises may not be appropriate for all team members, and that it is better have team-building exercises related to collaboratively solving the sorts of problems members are likely to face at work.[22] Finally, social cohesiveness can be facilitated by something as mundane as managing the team’s size. Teams that are smaller tend to be more cohesive, so if a team has much more than twelve or fifteen members, a manager may be wise to subdivide it.[23]

The importance of attending to social cohesion increases along with group diversity, since diversity reduces similarities; this may help to explain why some managers are reluctant to create diverse teams. Even so, there are many benefits of selecting team members with maximal diversity of function, tenure, age, ethnicity, and even personality, to ensure that the team includes a variety of perspectives and experiences to draw on in its work. Research indicates that diversity enhances creativity and satisfaction.[24] However, if not properly managed, diversity may contribute to significant problems in social interactions, which may lead to lower team performance, less communication, more disagreements, and the withdrawal of team members from the group.[25]

Social norms begin to develop in this first stage. They include the development of rules for interaction among members (e.g., tactics for resolving disagreements, how meetings will be run, forms of communication) and guidelines for appropriate individual behavior (e.g., appropriate attire, personal items displayed on one’s desk). Ground rules are often initially suggested by the leader, but over time they will need to be further developed and agreed upon as a team. Eventually, these expectations will evolve into generally accepted norms of behavior (stage 3).

Task-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Forming

Alongside the process of promoting social cohesion, stage 1 is also important for establishing the team’s task cohesion. Task cohesion refers to members’ attachment and shared commitment to the group’s purpose and the means for achieving it. Task cohesion can be fostered by ensuring that team members have a role in decision-making, such as being invited to participate in establishing the team’s goals and the rules and procedures for achieving them. To encourage commitment, it is helpful for top managers to endorse the purpose and establishment of the team, and for the team leader to describe how the team’s tasks fit with and contribute to the rest of the organization. Some companies create a formal or informal contract—signed by the manager and members—that states the goal of the team. Of the many task-related team-building activities leaders can exhibit in this stage, any activities that help members clarify the roles they and others will be playing may have the greatest impact on team performance.[26]

Differences in FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Forming

While there are many similarities among the three management approaches when forming a team, there are also noteworthy differences, many of which extend into subsequent stages of team development. First, each management approach describes how the team goals fit with the overall organization, but in addition a SET approach will also describe how the team goals fit with the larger socio-ecological realm. In this way the scope of task cohesion in SET management is broader than TBL management, which is in turn broader than in FBL management.

Second, each management approach seeks to develop both task cohesion and social cohesion, but consistent with its consequential utilitarian instrumental focus, an FBL approach is likely to place greater emphasis on task cohesion than on social cohesion. In contrast, given its virtue ethics focus, a SET approach is likely to place greater emphasis on social cohesion than an FBL approach would.

Third, each management approach draws attention to team boundaries, but for slightly different reasons. The FBL approach is likely to identify boundaries to identify competitors, whereas the SET approach is more likely to identify boundaries to understand who the organization’s neighbors are. Sometimes the FBL approach even advocates friendly competition within a firm, such as when the sales team in one geographic region competes against the sales team in another region. This competition is meant to motivate each team to sell more and thus increase overall company sales. The underlying logic is that each team will be more cohesive if its members feel that they must unite in order to do well compared to a different team. In contrast, SET managers are likely to increase social cohesion by showing how a team, through cooperation with others, can make a significant difference for the organization and its stakeholders.

All three approaches affirm having a diversity of members on teams, but a SET approach is most likely to also invite input, and sometimes participation, from suppliers, customers, and possibly even community members. Also, a SET approach may deliberately design team membership to be more transient in this stage than an FBL approach would, as members move in and out to explore the team’s purpose and to provide input. Recall that Semco had a “Lost in Space” program where new hires could participate in several teams before choosing one as their home (see Chapter 10). The emphasis for SET team members during this stage is exploring potential roles instead of having managers defining member’s specific roles. Eventually, through discussion, a core of committed team members emerges, and the forming stage draws to a close.

16.3.2. Stage 2: Storming

The second stage of team development is storming. While conflict and disagreement are the hallmarks of this stage, it is important to note that disagreement and conflict are also evident in the other stages (though not as intensely) and that their ongoing management can be seen as a central aspect of the leading function. Organizational conflict occurs when one member or unit challenges another. In order to understand conflict, it is helpful to differentiate between a traditional versus an interactionist understanding of conflict, and to differentiate between relational versus task conflict.[27]

A traditional understanding of conflict considers it to be dysfunctional. From this perspective, conflict undermines organizational performance, and managers should reduce or eliminate conflict. Team conflict can be reduced by rewarding members for not challenging the status quo, and for socializing members to think along the same lines. However, minimizing conflict has some costs and can result in groupthink.[28] Groupthink is the tendency of team members to strive for and maintain unanimity in decision-making rather than thoroughly considering all alternatives. Too little conflict can reduce creativity and innovation, frustrate members, and lower the quality of decision-making. The causes of groupthink include pressures for team members to conform to the majority view, rationalizations that highlight the positive and discount the negative aspects of an issue, isolation of an insular group that has minimal contact with outsiders, stressful working conditions that promote quick decisions, and leaders who are controlling and dominating.

An interactionist understanding of conflict considers it to be functional and even necessary for organizations to flourish. According to this perspective, there is a bell-curve shaped relationship between conflict and organizational performance: too little conflict is dysfunctional because it creates groupthink and does not generate new ideas, whereas too much conflict is dysfunctional because it creates chaos. The right amount of conflict is somewhere in between, where it fosters a healthy amount of self-reflection, learning, and innovation. The challenge for leaders is to manage the tension between too little and too much conflict in a healthy way that nurtures well-being.

It is also helpful to distinguish between relationship conflict and task conflict. Relationship conflict is evident when team members have interpersonal, non–task-related incompatibilities. This might arise from personality, political, or religious differences. Relationship conflict may also happen when two members are competing for the same position or role on a team. Traditionally there has been some agreement that relationship conflict is generally negatively related to the performance of a team (akin to the traditional view of conflict), though there is also some evidence to suggest that it can heighten members’ self-awareness and a team’s well-being (as described in opening case).

Task conflict is evident when members express differing views about the task being performed, or the best way to perform it. For example, should the team purchase existing software or develop its own? What is the best way to arrange the assembly line to build a car? Task conflict is sometimes called cognitive conflict, and is generally viewed as a positive if it does not occur in extremes (akin to the interactionist view).

Let us now consider the key aspects and behaviors at play in stage 2.

Relationship-Oriented Issues in Storming

In this stage, members are primarily concerned about whether they want to accept their role in the team and whether they trust their team members to work in the best interests of the team. Whereas in the forming stage, members tended to keep their differences to themselves, in the storming stage they become more open in expressing their concerns and disagreements. Conflict may arise when individual group members do not get along with one another, perhaps simply because of personality differences. Such differences are inevitable but can be disruptive if they get in the way of the everyday functioning of members.

A focal point in this stage is developing and disputing the group norms, formal and informal standards, and values that will guide the team in subsequent stages (norming and performing). In other words, a key task in this stage is to begin to develop agreed-upon organizational scripts that will guide future behavior of the team (see the discussion of organizational scripts in Chapter 7). Members will be able to engage more fully in the work of the team if the team’s norms and demands are aligned with their own values, interests, and understanding of how the team can best fulfill its purpose. As part of this process, members may become more assertive in choosing or defining their desired social position or role on the team, which may include some jockeying for power and control.

Task-Oriented Issues in Storming

The task-oriented issues in the storming stage parallel the relationship-oriented issues. As the purpose of the team becomes clearer, members need to become comfortable with their role and expected contribution before they commit to it. This includes committing to their particular responsibilities on the team, which take place in the context of task interdependence. Task interdependence is the degree to which the actions and outputs of one task influence, and are influenced by, the actions and outputs of another. If team member A’s task completion is not influenced by team member B, and B’s task completion is not influenced by A, then those two tasks are independent of each other. However, tasks in teams are by definition interdependent. For example, task interdependence is common in student group projects, where each member of the group may be expected to complete a different part of the group’s assignment, and each of the parts must be aligned. Conflict will arise if one member fails to complete their part of the assignment adequately, because this frustrates other members’ ability to complete their parts of the project, especially when everyone’s research and unique input are needed to solve a complex case. Generally speaking, the greater and more complex the task interdependence, the greater the likelihood for task conflict among team members.

Relationship-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Storming

The manager’s most important role in this stage is to manage interpersonal relationships and competing interests and agendas. Relationship conflict can be managed in a variety of ways, of which we will highlight four. First, leaders must avoid being the source of relationship conflict. This is very important, as leadership behavior is the most important factor in understanding member well-being.[29] For example, team leaders should exhibit relationship-oriented behaviors such as considerateness, and not only task- or change-oriented behaviors (see Chapter 15).

Second, team leaders should model healthy responses to interpersonal challenges in the workplace. This can be done by welcoming and trying to learn from members whom they might find personally challenging. This is related to being open-minded, non-judgmental, practicing critical self-reflection, and accepting negative feedback. This is not easy to do, but when managers demonstrate that they can control their emotions, not overreact, and even change as appropriate, it sends a powerful message to others on the team. Conversely, leaders send a negative message if they model pettiness, retribution. and intolerance toward views that differ from their own.

Third, team leaders must model tolerance of differences, but at the same time exhibit zero tolerance for bullying behavior in the workplace. Members must be able to trust leaders to ensure a safe workplace. Too often managers and others have turned a blind eye to unacceptable behavior in the workplace. Movements like #MetToo and improved training for managers and others in how to deal with bullying has helped, but there is still much work to be done. This includes ensuring the organization has supports in place for counseling and for holding bullies accountable.[30]

Fourth, team leaders can help members step back and reappraise events that have led to a specific relationship conflict and show when what was perceived as a personal attack was not intended that way. Such an event may happen when one member tells a colleague, “My way of performing a task is better than your way,” and thinks of this as a (functional) task conflict, while the colleague interprets it as an attack on their ego and thus as a (dysfunctional) relationship conflict.[31] Once both members become aware of the misunderstanding, both will be more likely to avoid such misinterpretations in the future.

Task-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Storming

While the danger in the storming stage is that there is too much conflict, it is important for leaders to remind themselves that having moderate amounts of task conflict is functional. Therefore, when leaders observe task conflict in a team, and especially when that task conflict is challenging the leader’s views about the team’s aims and means, the leader’s first reaction should be to exhibit a receptive, listening posture. This serves two purposes. First, it models behavior that can de-escalate dysfunctional conflict throughout the team. It would be good if everyone listened to challenging views before judging them. Second, listening to others may help leaders improve their understanding of the team’s task. In other words, the leader models behavior that promotes functional conflict.

One tool to accomplish this is called transformational conflict resolution, which emphasizes dialogue or conversation to help each person better understand the other’s perspective, and to be mindful of the person behind the perspective. By reframing the conflict as an investigation of assumptions and a search for mutually beneficial alternatives, participants in the conflict can become more self-aware and empathetic.[32] Managers using a transformative approach address conflicts by asking questions and offering suggestions that prompt team members to look at conflicts from a higher level of abstraction, moving from individual concerns to system concerns, and from parts of an issue to a broader view.[33] When dysfunctional conflict is caused by task interdependencies among team members, a leader may be able to resolve the problem by redesigning and improving the underlying systems related to the interdependencies.. This could include, for example, re-engineering the production process so that team members are less reliant on others to complete their jobs. Thus, if you are working on a group project where you need to complete your part and hand it off to a team member by the 15th of the month, your team leader may ask you to submit it by the 14th of the month, so that if there are any last-minute difficulties it will not slow down the next step in the process.

In sum, during the storming stage, it is critical for a manager to model healthy ways to deal with conflict, intentionally nurture mutual understanding and trust within the group, and affirm functional task conflict while defusing it when it’s dysfunctional. At the same time, the manager needs to be sensitive to the possibility that team members will tire of working through these differences. Thus, managers should look for opportunities to celebrate progress and refresh relationships, perhaps by something as simple as scheduling a celebratory dinner for the team. However, if team-building activities and the manager’s facilitative behavior fall short of alleviating the concerns of team members, the manager may need to disband the team (or remove some members) and form another team. In other words, some teams do not make it through stage 2, and thus never enter stage 3 of the team development process.

Differences in FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Storming

Managing conflict is necessary in all three management perspectives, but there will be different orientations and approaches for each.[34] For example, all three management perspectives recognize the value of team diversity and task conflict for promoting innovation and creativity. However, a SET approach will place greater emphasis on diversity as it pertains to the social and ecological externalities associated with a team’s activities than a TBL approach does, which will be greater than an FBL approach does. As a result, SET teams are more likely to be more innovative and creative in addressing social and ecological issues.

While all three approaches promote moderate amounts of task conflict, they have differing to relationship conflict. FBL management is the most likely to ignore relationship conflict, which allows it to fester and undermine social well-being in the workplace.[35] Moreover, managers who focus on instrumental outcomes, and who see interpersonal relationships primarily as a means to improve instrumental outcomes, are more prone to contribute to unhealthy workplace relationships themselves.[36] Taken together, such management contributes to the lack of social well-being many people experience at work (see Chapter 5).

In contrast, SET managers value healthy interpersonal workplace relationships because they are intrinsically valuable, not only because they can increase financial well-being. As a result, SET managers will be more likely to model healthy relationships and be more attuned to creating a space where other members can too. A SET perspective seeks to create teams where members agree on relationship-related norms that value members openly sharing disagreements with one another, where members are appreciated for their unique attributes, and have a mutual sense of responsibility to care for each other (see ethic of care, Chapter 15). Developing strong relationships provides the foundation for addressing task-related issues. This was at the heart of Kate Cassidy’s experience as a member of the counseling team at camp: Cassidy had a greater sense of community with her team because of what she called healthy conflict. She and the other team members embraced their differences which, even when not directly related to their tasks, transformed the meaning of their tasks for themselves and for their campers.

Test Your Knowledge

16.3.3. Stage 3: Norming

As teams emerge from the storming stage and enter into the norming stage, the group identity and norms that they have been developing (and disputed) start to become established and accepted as guides for subsequent behavior. In the norming stage, members agree on norms or shared mental models of the best ways to complete tasks and the appropriate ways to interact with one another.[37] These shared norms can in turn promote group performance (stage 4) because they provide regularity, help the group avoid interpersonal problems, and signify the group’s identity.[38]

Relationship-Oriented Issues in Norming

After successfully navigating the storming stage,[39] relationship issues become much less intense, and members come to feel secure and accepted and have an optimistic view of the future. They are motivated to show their support for each other and to contribute their skills and effort for the work of the team. There is strong participation and a commitment to work together in adhering to their team norms. Team norms can have informal aspects (e.g., dress code, whether members work overtime to help each other meet deadlines) and formal aspects (e.g., the frequency of group meetings, processes for sharing information). This is a time of harmony and high social cohesion, with members looking out for each other.

Task-Oriented Issues in Norming

A focus in this stage is on completing the development of —and then embracing—a shared vision of the team’s purpose. The general purpose of the team has been introduced in stage 1, perhaps fought over and clarified in stage 2, and is now fine-tuned and supported in stage 3. This support is linked directly to a clear understanding of how the team will enact its purpose (means), and to ensuring that members’ tasks and roles align to meet the team’s goals. Two team norms (information sharing and workload sharing) are particularly important given the task interdependencies that are necessary to fulfill the team’s purpose.

With regard to information sharing, it is important that the lines of communication in a team remain open, and that team members don’t unthinkingly accept the status quo (i.e., groupthink). The commitment to the norm of information sharing is essentially a commitment to continuous organizational learning and to ensuring that team members do not become too complacent. It means establishing a general norm that says that it is desirable for other norms to be changed when appropriate.

In terms of workload sharing, it is important that members perceive one another as doing their fair share of the team’s work. This includes establishing norms regarding how much effort is expected from each team member, what sorts of competencies are necessary, and how much members will help one another (i.e., engage in organizational citizenship behavior).

Relationship-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Norming

Leaders play a critical role in establishing and promoting team norms.[40] This includes providing reinforcement for positive norms, and knowing how and when to step back and facilitate self-managed teams where members themselves develop and take ownership of the norms that will guide their teamwork. It also includes explicitly planning times to celebrate successes in developing norms, and recognizing harmonious relations. These harmonious relationships are evident in Cassidy’s team experience, where members welcomed and embraced the differences among each other rather than expecting everyone to aspire to follow the scripts associated with a stereotypical counselor.

Task-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Norming

Leaders can play an important role in setting the norms around task-related information sharing and workload sharing within teams. Regarding information sharing, the key is for leaders to develop norms that prevent both too little information sharing (e.g., hoarding of information, groupthink) and too much information sharing (e.g., being overwhelmed by unfiltered information sharing; see Chapter 17) as work practices are developed and fine-tuned in practice. Team members may withhold information for a variety of conscious and unconscious reasons. For example, when Cassidy was a rookie member of the counselor team, she was trying hard to fit in and not sharing ideas about how things could be improved. Sometimes team members may intentionally withhold information to speed up the decision-making process once a satisfactory option is presented, or withhold information that goes against their own self-interest.

With regard to workload sharing, if any team member is perceived not to be doing their fair share of the work, other team members will try to determine the cause. If the cause is perceived to be a lack of ability, then team members may be willing to help the poor performer.[41] If the lack of performance is perceived to be caused by an external factor (such as the actions of a supplier or customer, faulty equipment, and so on), then efforts will be made to change the external factor. But if poor performance is perceived to be due to a lack of effort—sometimes called free riding[42]—then team members are likely to punish the free rider in an attempt to correct the unacceptable behavior. Or they may withhold effort themselves lest they become a sucker ( someone whose hard work is taken advantage of by a free rider).[43] In this way one free rider can create a downward spiral of reduced effort throughout the team (see discussion of equity theory, Chapter 14). To avoid the sucker effect, a leader needs to be aware of and address issues of motivation within the team.[44] Free riding is most common when individual contributions are difficult to monitor or measure, when the team is perceived to be highly capable, or for team members who are low in conscientiousness.[45] Techniques to reduce free riding include developing norms that make contributions explicit, monitoring team member contributions, and requiring accountability for individual contributions. For example, when a camp counselor is not doing their share to ensure that the campers are having a good time, the camp director may take the counselor aside for a discussion, or perhaps give the counselor specific assignments that are easier to monitor (e.g., put the counselor in charge of the evening’s recreational activities).

Finally, a team’s work-sharing norms can also influence and be influenced by consistent contributors who contribute to the team regardless of how little their teammates offer ( essentially the opposite of free riders).[46] It turns out that consistent contributors, in addition to not stooping to the level of free riders, may also benefit from other rewards for their efforts. For example, it seems that just as free riding may be contagious, consistent contributing can also be contagious, where a team’s norm of consistent contributing increases over time (though this may take a long time and is not guaranteed to happen). Leaders may be able to enhance consistent contributing norms by modeling such behavior themselves.

Differences in FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Norming

We can identify two differences among the approaches to norming. First, a SET approach tends to have a larger understanding of a team’s purpose because it includes an emphasis on enhancing social and ecological well-being. Compared to FBL and TBL approaches, a SET approach to information sharing is therefore more likely to include a broader set of external stakeholders and include more information about ecological performance.

Second, a SET approach to workload sharing is more likely than the FBL and TBL approaches to seek to encourage consistent contributing rather than minimize free riding.[47] The SET approach involves explicitly recognizing, rewarding, and supporting positive behavior rather than establishing systems that are designed to identify and minimize negative behavior. For example, when managers at Semco (see Chapter 10) realized that team members were stealing equipment from the firm, it was suggested that they set up monitoring systems to catch the individuals to discourage future bad behavior. Instead of doing this, managers trusted that this behavior would be overcome by positive norms amongst team members and cease. Their trust was rewarded, and as a result costly monitoring was avoided (the managers never did find out precisely why the stealing stopped).

Test Your Knowledge

16.3.4. Stage 4: Performing

If they are fortunate enough to enter the fourth stage—performing—team members have developed social and task cohesion, understanding and appreciation of the team’s purpose, and practices that enable them to perform their interdependent tasks at a high level.

Relationship-Oriented Aspects in Performing

Ideally, team members in this stage feel that they are included and respected members of the team, have feelings of pride and confidence in their ability to reach the goals of the team, and experience a sense of belongingness and meaningful work.[48] They function as a cooperative community and have a positive group identity. Of course, many teams fall short of these ideals and continue to exhibit aspects of forming, storming, and norming.

Task-Oriented Aspects in Performing

In the performing stage, team members welcome recognition of a job well done along with feedback that will enable them to meet the challenges of improved performance and new goals. There is a healthy match between members’ abilities and the tasks and roles they perform. Members are often willing to assume increasingly more responsibility in self-managing the team.

Relationship-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Performing

Leaders do their part to ensure that the team remains a supportive community. This often means letting the team self-manage as much as possible, and stepping in only to provide uplifting feedback or when problems arise. Regardless of whether these problems arise from tensions between members or with other stakeholders, the leader should carefully listen to the people involved and consider their counsel. When there are problems, managers should try not to engage in behaviors that promote blaming and defensiveness. Rather, they should reframe failures or shortcomings as problem solving and learning opportunities.[49] For example, a viral video on Twitter (now X) showing racial bias in a Starbucks prompted the development of new regulations and a company-wide training session to address racial bias.[50]

Task-Oriented Leadership Behaviors in Performing

One way that leaders can maintain and improve team performance is by managing the motivation of team members through providing appropriate rewards and feedback. These rewards can be based on individual or team performance, though team-based rewards are often preferred.[51] Focusing on team goals, feedback, and rewards unites members in pursuit of a common goal, encourages cooperative behavior, and facilitates increased collective effort and performance.[52] Another reason to provide team-based feedback and rewards is that team performance metrics may be more readily available and easier to quantify than individual performance metrics. Also, from a practical standpoint, it is often impossible to separate the contributions of each individual when members must work interdependently.[53]

Concerns about free riders in teams may encourage managers to provide feedback and rewards to individual team members, even though rewards based on individual performance may be a barrier to optimizing team performance.[54] Although most team members acknowledge that managers have a legitimate right to provide individual ratings (and most members believe managers to be less biased than fellow team members), they often believe that managers lack adequate information to rate their work accurately, especially in cases where a manager is external to the team or doesn’t spend much time with the team.[55] Organizations often provide rewards and feedback at both individual and team levels. For example, athletes on sports teams may receive bonuses for individual performance and for team performance.

Differences in FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Performing

The differences between the three management approaches in this stage are consistent with many of the differences in the ongoing performance of organizational work, as described in other chapters (e.g., decision-making, goal-setting, organizational design, motivating, leading, and so on). Some distinctions related to key leadership behaviors include FBL perspective would place the greater emphasis an FBL approach would place on the leader’s direct role in managing the team and providing extrinsic reinforcement, whereas a SET manager would be more likely to offer ideas and feedback informally and emphasize learning and shared power as sources of intrinsic motivation. Furthermore, whereas an FBL-based management might be inclined to offer individual rewards, a SET-style approach will likely be more open to team-based rewards. If individual recognition or rewards are deemed necessary, a SET manager would be inclined to have teams decide these rewards. This is illustrated by how the company W. L. Gore (which manufactures GORE-TEX Fabric, among many other products) uses compensation teams to decide how individuals are rewarded for work within their teams as well as for work that spans several teams, including work like coaching and mentoring that has helped others to succeed.[56]

16.3.5. Stage 5: Adjourning

The fifth stage—adjourning—occurs when a team disbands. This fifth stage is not always discussed in the research but it is worthy of consideration. The adjourning and forming stages can be seen as opposite sides of the same coin. Just as in the forming stage, in the adjourning stage members are likely to experience anxiety about the uncertainty ahead of them, but they can also be excited for the transition to something new. And just as members in the forming stage are cautious about showing their true selves, some members in adjourning may be reluctant to show their true feelings of emotional attachment, while other members may be very expressive about their fondness for their team members. Members of high-performing teams will often gather socially long after having adjourned as a formal team (see this chapter’s opening case).

With regard to the task-oriented dimension, whereas members in the forming stage are unsure what their purpose is and what their work will entail, members in the adjourning stage of a successful team look back with pride in having accomplished their team goals, in their collective ability to work together as a team, and in the skills and experience they acquired in their time together. Members may bask in the glow of their individual and team achievements and may be saddened by the loss of friendship and camaraderie. It is important that leaders ensure that team members are recognized and that there is a “closure” event that clearly marks the end of the team’s formal activities together. It can also be appropriate to provide some sort of physical memento members can put on their desk to recall a job well done.

Test Your Knowledge

16.4. Entrepreneurial Implications

Teams are vitally important in entrepreneurship. This is true at two levels. First, new start-ups often share many characteristics associated with the development of a new team, as they are collections of people who are taking on a new purpose and task. Second, new start-ups are often created by a top management team of entrepreneurs (recall from Chapter 6 that start-ups with a management team are more likely to succeed than ones started by single entrepreneurs). A start-up organization needs the range of skills, experience, resources, and contacts that a team can provide. Information sharing and functional conflict are essential ingredients for entrepreneurship, but they demand strong leadership skills in managing conflict and team building. In a new organization with no history and few procedures, it is easy for conflict to lead to chaos, animosity, and poor performance.

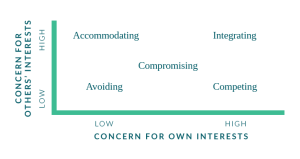

Entrepreneurs, even more than most managers, need to be able to address team conflict in a productive way. An important aspect of this is for entrepreneurs to become aware of their preferred conflict management style and the preferred style of other team members. The specific way that someone deals with conflict depends on two factors: concern for one’s own interests, and concern for others’ interests.[57] A high concern for one’s own interests tends to result in assertive behavior, whereas a high concern for others’ interests tends to result in cooperative behavior. Figure 16.2 shows five conflict management styles that represent combinations of assertive and cooperative behavior.

Figure 16.2. Five conflict management styles

- Avoiding is a passive response to conflict that is both uncooperative and unassertive. Avoidance is marked by withdrawal from conflict or suppressing the reasons why the conflict has occurred.[58] This approach may be useful in situations where conflict may be too costly to resolve or where the issue is very trivial and not worth managing. The drawbacks of avoiding include missing opportunities to provide input and leaving both parties in the conflict frustrated.

- Accommodating—sometimes referred to as obliging—features a high level of cooperativeness but a low level of assertiveness. It places the other parties’ needs first as a way to reconcile conflict.[59] Accommodating may be useful when harmony is important, for building social connections, or if the issue is more important to the other party than to oneself. Drawbacks include failing to address legitimate personal interests, and unresolved and reduced cohesion because the accommodator feels used or taken advantage of. While accommodating team members may help the team move forward in the short term, their concerns must be addressed at some point if they are to be fully engaged in the team’s work.

- Competing—sometimes called dominating—reflects a high level of assertiveness and a low level of cooperation. This conflict management style is characterized by a strong desire to satisfy one’s own needs and to “win” the conflict in one’s own favor.[60] A competing style may be useful if a quick decision is needed, or if a decision of importance needs to be made in a short time period. Drawbacks include overlooking others’ legitimate concerns and damaging relationships such that the conflicting parties do not want to work together in the future. This is not a sustainable approach to develop a high-performing new venture.

- Compromising has a moderate level of both cooperativeness and assertiveness. It requires each side to give up and receive something of importance.[61] Compromise may resolve some issues, but it creates the potential for both parties to feel somewhat dissatisfied. It may be useful if both sides are equally powerful, if a temporary solution is needed, or when it is genuinely not possible to find a win-win solution. Drawbacks of compromising include lost creativity and arriving at suboptimal decisions by offering compromises too early in the discussion.

- Integrating—sometimes referred to as collaborating—reflects a high level of cooperation and a high level of assertiveness. This style focuses on creating a solution that satisfies all parties.[62] Integration is most useful when all interests in the conflict are too important to compromise and when consensus is needed. The drawbacks of this style of managing conflict include the risk of making an otherwise simple decision very complex, and the amount of time and effort that can be required.

People choose among these different styles depending on the situation, though most people have a preferred style. Knowing the different types of conflict management styles and their benefits allows an entrepreneur to adopt the most appropriate type for the situation at hand. For example, if the health of ongoing relationships is important, and if different interests and opinions are critical to effective decision-making, the entrepreneur should generally use an integrating style.

Knowing the different styles also enables the entrepreneur to recognize them in others. Research indicates that individuals’ preferred conflict styles usually reflect their personality, culture, and history. For example, people with collectivist orientations are more likely to prefer integrating and compromising styles than people with individualistic orientations (see Chapter 5).[63] The opposite is true for avoiding, which individualistic people prefer more than collectivistic people do. When working with a team, it can be very helpful to consider how members are likely to react based on their preferred conflict management style.

With this knowledge, entrepreneurs can take steps to reduce the negative effects of team members’ conflict styles. The entrepreneur can intentionally draw out some members (e.g., avoiders) and restrain others (e.g., competitors) to create a more productive discussion. In some cases, an outside facilitator or mediator may be helpful. For example, Tall Grass Prairie Bread Company makes frequent use of mediators for board decision-making and for training staff generally (see Chapter 7). Another useful approach to managing different conflict styles is to set out ground rules for handling conflict. A team may agree that before any decision is made all team members must share their thoughts on the alternatives, or that before a team member restates an opinion in a conflict, they must be able to verbalize the interests of the other parties to their satisfaction.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Organizations contain both groups and teams. A group is a collection of three or more people who share a common interest or association, whereas a team is a collection of three or more people who share task-oriented goals, work interdependently as a unit, and are accountable to one another to achieve those goals.

- Many teams (and groups) can be seen as progressing through a series of somewhat predictable developmental stages.

- Stage 1: Forming. The team is created, and members are excited and apprehensive as they begin the process of developing social and task cohesion.

- The FBL approach focuses on task cohesion more than on social cohesion; it draws attention to team boundaries and competitors, and describes how team goals fit with rest of the organization.

- The SET approach focuses on social cohesion as much as on task cohesion; it draws attention to team boundaries and neighbors, and describes how team goals fit with the rest of the organization and with the socio-ecological realm.

- Stage 2: Storming. Team members experience conflict as they try to influence how the group will function, the goals the group will pursue, and the roles and individual responsibilities that will emerge in trying to achieve those goals.

- The FBL approach embraces moderate task conflict but tends to ignore relationship conflict.

- The SET approach embraces moderate task conflict and relationship conflict.

- Stage 3: Norming. The team establishes norms and a shared vision as members fine-tune their roles and responsibilities.

- The FBL approach focuses on information sharing related to the team’s goals, and seeks to minimize free riding.

- The SET approach focuses on information sharing related to the team’s goals and to socio-ecological goals, and seeks to enhance consistent contributions.

- Stage 4: Performing. The team excels at its task and enjoys high social and task cohesion.

- The FBL approach focuses on extrinsic reinforcers, often for members individually.

- The SET approach focuses on intrinsic reinforcers, typically for the team collectively.

- Stage 5: Adjourning: The team disbands, celebrating its accomplishments and the sense of community that developed during its existence.In each of the five stages, a TBL approach is consistent with FBL practices, unless there is a business case supporting the adoption of SET practices.

- Stage 1: Forming. The team is created, and members are excited and apprehensive as they begin the process of developing social and task cohesion.

- Given the heightened opportunities for conflict in a new venture, it is particularly valuable for entrepreneurs to choose the particular conflict management styles appropriate for the various situations they will face.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- What is the difference between a group and a team? Provide an example of each from your own personal experience.

- Reflect back on your experiences as a member of school teams (e.g., sports teams or study teams). How consistent was your team experience with the stages of development described in this chapter? In what ways did your experience differ? Do you feel that you learned any important life lessons from your team experience?

- As a manager, what actions would you take to improve the social and task cohesiveness of your team?

- Identify your preferred conflict management style, and list and briefly describe the benefits and drawbacks of your style. When does it work best, and when might you want to use another style?

- Suppose you are asked to head up a problem-solving team. Identify information sharing techniques that will reduce the likelihood of groupthink, and how their use will improve the decision-making of the team.

- How do you typically respond to free riders in a team that is completing a group assignment? Does the perceived cause of free riding influence how you respond?

- Have you ever been on a team with a consistent contributor? What effect did the consistent contributor have on the rest of the members? Were they treated like a sucker, or were their actions contagious?

- Reflect on experiences where your performance was evaluated by your team members. If you have no experience in this area, how do you think you would respond to team members giving feedback that influences your grade?

- List some of the differences in the techniques used by FBL and SET managers during each stage of team development. Where do you think TBL managers would be more likely to use FBL or SET techniques? Give examples and explain your answer.

- If you were to start a new venture, would you prefer to do it on your own or as part of an entrepreneurship team? Explain pros and cons of both. Describe your preferred conflict management approach, and then describe what sort of conflict management approach you would like others in your start-up to have. Does it make a difference whether the others are part of the top management or if they are people hired to work for you?

- For research looking at different stages sports teams go through, see Kheel, S., & Kim, K. (2016). School based club sport experience from group developmental perspective. In The 28th International Sports Science Congress (pp. 102–103). ↵

- For an article looking at different stages camp teams go through, see Curiel, H. F. (2016). Group work camp memories: Group power. Groupwork, 26(3): 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1921/gpwk.v26i3.1047 ↵

- The quotes and much of the description in the opening case are taken from Cassidy, K. J. (2013). The essence of feeling a sense of community: A hermeneutical phenomenological inquiry with middle school students and teachers [Doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of Education, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario. This quote is from page 5, and other quotes below are taken from pages 4 to 5, and pages 115 to 117. ↵

- For more thoughts on building a sense of community among diversity, see Cassidy’s more recent publication: Cassidy, K. J. (2019). Exploring the potential for community where diverse individuals belong. In S. Habib & M. R. M. Ward (Eds.), Identities, youth and belonging: International perspectives (141–157). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96113-2_9 ↵

- Varma, A., Jaiswal, A., Pereira, V., & Kumar, Y. L. N. (2022). Leader-member exchange in the age of remote work. Human Resource Development International, 25(2): 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2047873 ↵

- Popoola, O., Adama, H., Okeke, C., & Akinoso, A. (2024). Conceptualizing agile development in digital transformations: Theoretical foundations and practical applications. Engineering Science & Technology Journal, 5(4): 1524–1541. https://doi.org/10.51594/estj.v5i4.1080 ↵

- Cohen S. G., & Bailey D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23(3): 239–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(97)90034-9 ↵

- Crocker, A., Cross, R., & Gardner, H. K. (2018, May 18). How to make sure agile teams can work together. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/05/how-to-make-sure-agile-teams-can-work-together ↵

- Kohnová, L., and Salajova, N. (2021). Agile organizations: Introducing self-managed teams. In D. Cagáňová, N. Horňáková, J. Papula, K. Stachová, & L. Kohnová (Eds.), Management Trends in the Context of Industry 4.0. EAI. http://doi.org/10.4108/eai.4-12-2020.2303550. ↵

- Cohen, S., Ledford, G., Jr., & Spreitzer, G. (1996). A predictive model of self-managing work team effectiveness. Human Relations, 49(5): 643–676. http://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604900506 ↵

- Sauer, S., & Nicklich, M. (2021). Empowerment and beyond: Paradoxes of self-organised work. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation, 15(2): 73–90. https://doi.org/10.13169/workorgalaboglob.15.2.0073 ↵

- According to Sinclair , “the effectiveness of teams depends on the extent to which their application is informed by ideology, on the one hand, or careful and critical appraisal, on the other. The extent to which the team ideology is unquestioningly embraced will determine how fruitful is the experience of participation with groups. It is the ideology, rather than the team itself, which tyrannizes, because it encourages teams to be used for inappropriate tasks and to fulfill unrealistic objectives. By developing a more critical appreciation of the costs and limitations of teams, they will be put to better use.” Page 622 in Sinclair, A. (1992). The tyranny of a team ideology. Organization Studies, 13(4): 611–626. http://doi.org/10.1177/017084069201300405 ↵

- Yee, M., & Edmondson, A. (2017). Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37(1): 35–58. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.002 ↵

- For example, this includes diversity regarding what members believe and value about the “should’s” and “ought’s” of life. Stahl, G. K., Maznevski, M. L., Voigt, A., & Jonsen, K. (2010). Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4): 690–709. http://oi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.85 ↵

- Tolliver, J., & Sass, M. (2024, June 17). Hybrid work has changed meetings forever. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2024/06/hybrid-work-has-changed-meetings-forever. Kunert, P. (2025, Jan 15). Shove your office mandates, people still prefer working from home. The Register. https://www.theregister.com/2025/01/15/shove_your_mandates_people_still/ ↵

- Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence for small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6): 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100; Bonebright, D. A. (2010). 40 years of storming: A historical review of Tuckman’s model of small group development. Human Resource Development International, 13(1): 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678861003589099. Research also suggests that the progress of the team has much, and perhaps more, to do with the pressure of meeting deadlines. Gersick, C. J. G. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31(1): 9–41. http://doi.org/10.2307/256496 ↵

- Note that Table 16.2, and much of the discussion of each of the stages, draws from and builds upon Tuckman (1965); Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. (1977). Stages of small-group development revisited. Group & Organization Studies, 2(4): 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200404; Bonebright (2010); Cassidy, K. J. (2001). Bringing clarity to group development: Synthesizing a meta-framework from practitioner-authored group-development models [Master’s thesis]. Faculty of Education, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario; Dyck, B., & Neubert, M. (2010). Management: Current practices and new directions. Cengage/Houghton Mifflin. For more work on the ongoing issues that team members address throughout the stages, see Cassidy, K. (2007). Tuckman revisited: Proposing a new model of group development for practitioners. Journal of Experiential Education 29(3): 413–417. http://doi.org/10.1177/105382590702900318 ↵

- Sarkar, S. K., Ghosh, S., Roy, P., & Choudhury, N. R. (2025). Building champions: Leadership as the keystone of team performance. In T. S. Burris-Melville & S. T. Burris, Developing Effective and High-Performing Teams in Higher Education (pp. 91–114). IGI Global; Courtright, S. H., Thurgood, G. R., Stewart, G. L., & Pierotti, A. J. (2015). Structural interdependence in teams: An integrative framework and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6): 1825–1847. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/apl0000027; Adam, M. (2024). Perception and interpretation of team development phases and their changes: Factors influencing team development. The Eurasia Proceedings of Educational & Social Sciences, 37: 16–24. https://www.epess.net/index.php/epess/article/view/854/853 ↵

- Belbin, R. M., & Brown, V. (2022). Team roles at work (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163152. ↵

- Social cohesion is positively related to performance at all levels in the four-stage model, though one study found that when measured at the individual member level, social cohesion was not related to performance in the norming stage. Hall, T. B. (2015). Examining the relationship between group cohesion and group performance in Tuckman's (1965) group life cycle model on an individual-level basis [Doctoral dissertation]. Regent University, Virginia Beach, Virginia. ↵

- Mullen, B., & Copper, C. (1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2): 210–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.210; Jordan, M. H., Field, H. S., & Armenakis, A. A. (2002). The relationship of group process variables and team performance: A team-level analysis in a field setting. Small Group Research, 33(1): 121–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640203300104 ↵

- Greenfield, R. (2015). Startup vs. Wild. Bloomberg Businessweek, no. 4454: 9–101; Olsen, P. (2009, March 25). Team building exercises for tough times. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2009/03/teambuilding-exercises-for-tou; These examples are taken from Ektuna, T., & Van Heel, A. (2017). Developing teams in startups: A case study on startup team dynamics. [Master’s in management degree project]. Lund University, Lund, Sweden. ↵

- Of course, there is no “one best number” of people to have on teams, and the optimal number will vary depending on a variety of considerations, such as the complexity of the task, the diversity among member, and the personality of members. Some research suggests that the optimal group size for enhancing social and ecological well-being is somewhere between 150 and 200. These groups are further subdivided into subgroups or teams. See Casari, M., & Tagliapietra, C. (2018). Group size in social-ecological systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11): 2728–2733. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1713496115. Other research based on the “Dunbar number” suggests that humans can typically maintain about 150 casual friends (similar to the optimal group size for social and ecological well-being). Of these, fifty might be “buddies,” twelve “good friends,” and up to five “confidantes” who represent and inner circle of trust, and an average of 1.5 people who are our closest friends (on average the number of confidantes people have decreased from 2.94 in 1985 to 2.08 in 2004). We can keep track of about 500 people, and match names to faces of about 1,500. Wayne, T. (2018, May 12). Are my friends really my friends? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/12/style/who-are-my-real-friends.html ↵

- Paulus, P. B. (2024). Fostering creativity in groups and teams. In Handbook of organizational creativity (pp. 165–188). Psychology Press. ↵

- Milliken, F. J., & Martins, L. L. (1996). Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 21(2): 402–433. https://doi.org/10.2307/258667; Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., & Mount, M. K. (1998). Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3): 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.377 ↵

- Orgambídez, A., & Almeida, H. (2020). Social support, role clarity and job satisfaction: A successful combination for nurses. International Nursing Review, 67(3): 380–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12591. ↵

- For a review of this literature, see Dyck, B., Bruning, S., & Driedger, L. (1996). Potential conflict, conflict stimulus, and organizational performance: An empirical test. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 7: 295–313. ↵