Part 3: Organizing

13. Organizational Change

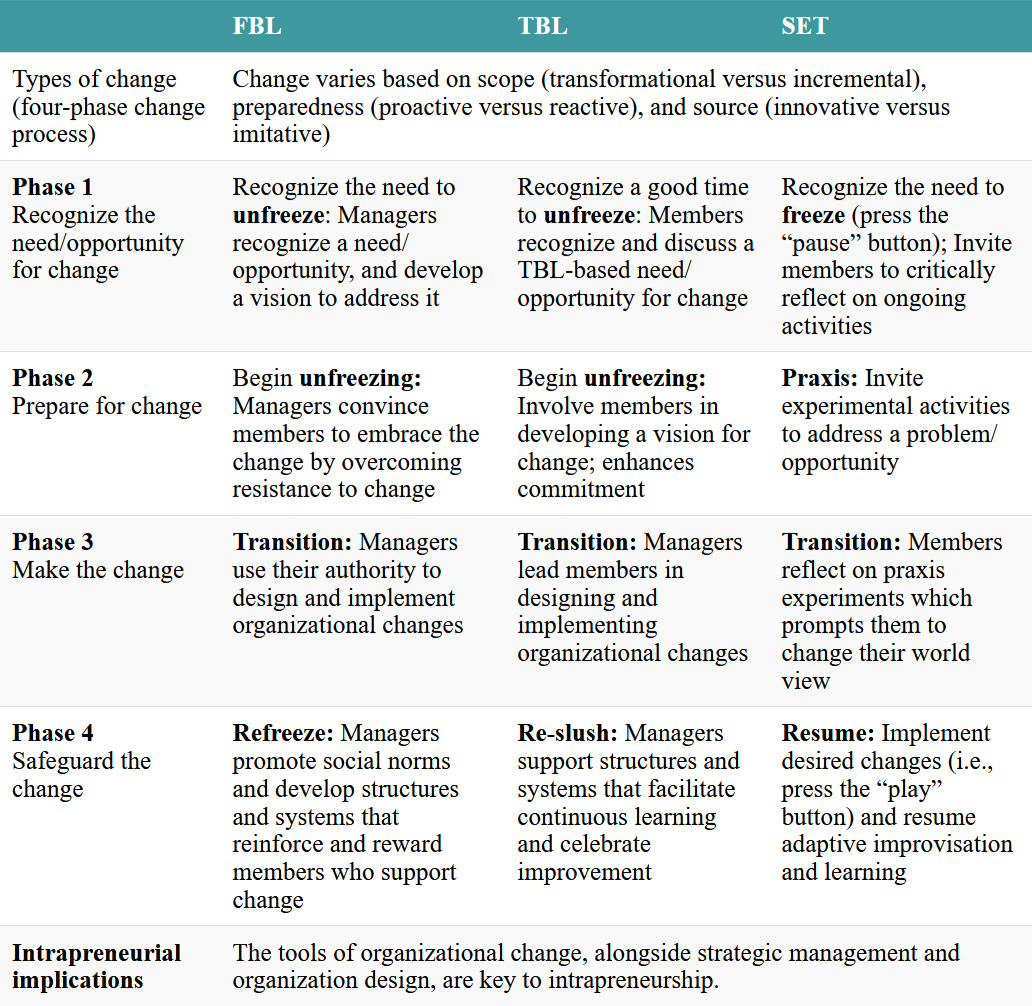

Chapter 13 provides an overview of the four-phase process of change, as summarized in the following table and in the whiteboard animation video.

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain how different types of organizational change vary in terms of scope, preparedness, and source.

- Describe organization life cycle theory and how it fits with the four generic types of organization design.

- Recognize the four generic phases of the organizational change process.

- Explain differences in the organizational change process in FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

- Explain how to use the tools of organizational change to support intrapreneurship

13.0. Opening Case: From Being Worthy of Jail to Creating Net Positive Externalities

Interface Inc., a manufacturer of carpet tiles that was founded about fifty years ago, is a well-known example of a traditional FBL business that has successfully managed to change, first into a TBL firm and then into a SET firm.[1] A market leader in over 100 countries where it competes, Interface has about $1 billion in annual sales, 3,500 employees, and dozens of factories in half a dozen countries.[2] To change a business of this size takes considerable skill and time. Interface’s use of the four-phase organizational change process is instructive.[3]

One of the biggest misconceptions is that Ray was the lone leader and by being the founder and CEO he could just edict the transformation and it would happen but that’s just not how you change a billion dollar organization. . . . what Ray laid out was potentially a complete transformation of the entire existing economy of the world” (manager).[4]

The first phase—recognizing the need or opportunity for change—started in 1994 when company founder and CEO Ray C. Anderson (1934–2011) was asked about Interface’s environmental performance. This was something he had not given much thought to, so he did some research. He says it struck him “like a spear in his chest” when he found out that each year Interface manufactured $800 million worth of products by extracting over 6 million tons of raw resources and producing over 10,000 tons of solid waste, 60,000 tons of carbon dioxide, and 700 tons of toxic gases while contaminating over 2 billion liters of water. “I was running a company that was plundering the earth . . . someday people like me will be put in jail.”[5] This prompted Anderson to develop a new vision for Interface: “Be the first company that, by its deeds, shows the entire world what sustainability is in all its dimensions: people, process, product, place, and profits by 2020.” In particular, Anderson wanted Interface to have net-positive ecological externalities, a challenge he likened to climbing higher than Mt. Everest.

While Anderson was convinced about the need for change, much work needed to be done to demonstrate the opportunity for change. His managers “needed to discuss whether it [would] be possible to create competitive advantages via sustainability.”[6] This was uncharted territory not only at Interface but also in the larger industry. To begin, Interface managers sought to understand what sorts of internal and external resources were available to address the challenge; this meant collecting and compiling existing information about policies, projects, green programs, eco-activities, and human resources. This led to managers learning about biomimicry (where the waste of one organism becomes food for another), principles of green product design, material recovery ideas where waste became inputs, and process improvements that could come from redesigning manufacturing facilities. They soon discovered that such changes would take time and would require considerable effort in preparing internal and external stakeholders.

The first phase ended with some TBL initiatives that Interface could implement relatively easily to create some “early wins” that would help to inspire future action. By the end of this phase, Interface had tripled its profits, doubled its employment, and was recognized in the Fortune 100 list of “Best Companies” to work for. But these quick fixes were still within the TBL management paradigm, and Anderson wanted Interface to become a SET organization.

The second phase—preparing to implement changes associated with SET management—began around 1999 and aimed at getting members to buy into SET thinking. As Anderson described, “Most of the managers viewed the new vision with hostility, confusion, and skepticism.”[7] External consultants were brought in to hold workshops designed to foster outside-the-box thinking and help members develop a holistic vision of sustainability covering all areas of the business. Key aspects included identifying new green business opportunities that could be created in-house or with external partners, and developing a deeper understanding of how Interface’s new compounder strategy would differentiate the firm in the marketplace. Its mission was to become a corporation that cherishes nature (minimizes negative externalities) and restores the environment (enhances positive externalities). As Anderson put it: “For those who think that business exists to make a profit, I suggest they think again. Business makes a profit to exist. Surely it must exist for some higher, nobler purpose than that.”[8]

The third phase—which involved actually implementing organization-wide changes consistent with SET management—started in 2003. This phase focused on reinventing Interface’s business model in terms of products, services, and processes. A key element in Interface’s renewal process was for leaders to support individuals and teams who promoted green experiments and initiatives, signaling that sustainability was not a fad but instead the new normal. In particular, instead of the previous system where worn-out carpet found its way into the landfill (“cradle-to-grave” products), Interface wanted worn-out carpet to be re-used to make new carpet (“cradle-to-cradle” thinking).[9] By 2006, aided by new suppliers, Interface was the first in its industry to develop a commercial recycle and reuse system. By the end of this phase, the company had saved over $400 million in reduced waste, reduced its fossil fuel use by 60 percent, cut 82 percent of its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions relative to sales, and reduced water consumption by 66 percent, all while doubling its earnings.

In addition to working to enhance ecological well-being, Interface also focused on social well-being, which Anderson referred to as the “soft side” of the business.[10] Anderson was thankful that others in the company rallied to this issue with the same passion he had for ecological well-being. For example, rather than exploit overseas working conditions, Interface built and operated its Asia-based factories to the same high standards as in North America, Europe, and Australia. Interface also encouraged its members to become involved in their local communities and successfully found ways to provide jobs in economically challenged communities (e.g., in Harlem, New York City). By 2004, Interface employees had volunteered almost 12,000 hours in community activities.[11]

The final phase, starting in 2008, was to safeguard the changes that had been made. This meant working with suppliers and customers to make sustainability the new normal in the larger industry[12] so that Interface’s SET analyzer organization design with a compounder strategy (Chapter 11) need not rely only on internal practices or specific leadership personalities. As one manager explained: “It is important to connect sustainability with performance measures, managerial performance scorecards, staff’s work duties, and the existing incentive systems.”[13]

Altogether, the four-phase change process at Interface took more than fifteen years: five years to recognize needs and opportunities and implement TBL initiatives, four years to prepare members for the changes based on SET management, five years to implement them, and then several years to safeguard them. Many transformational change attempts to adopt SET management do not make it past the first phase and simply celebrate “quick wins” without fundamentally changing the organization. Change attempts also often fail in the second phase to get members on board with the SET approach. Once the first two phases have been completed, the actual change begins in the third phase, where success can depend on generating and receiving adequate support from external stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, customers, government regulations).

13.1. Introduction

Thus far our discussion of the planning and organizing functions has focused on managing different processes within organizations such as making decisions, formulating and implementing strategy, and creating coherent organization designs. These are challenging tasks for managers, but even more challenging is to change an organization’s goals, strategy, or design, or to implement an intrapreneurial initiative. It is in times of change that the role of the manager may be most critical. In this chapter, we begin by describing three basic dimensions of organizational change and the eight specific types of organizational change that result. We then describe the four-phase process of change as it is carried out by Financial Bottom Line (FBL), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), and Social and Ecological Thought (SET) approaches to transformational change. We conclude by discussing implications for intrapreneurship.

13.2. Three Dimensions of Organizational Change

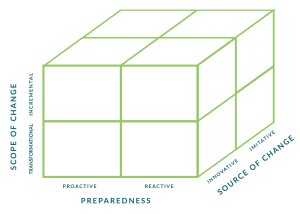

Organizational change is the substantive modification of some aspect of an organization. This can be a change to any one (or more) of the components that comprise an organization’s design, including change to its structure (e.g., its place along the mechanistic-organic continuum), culture (e.g., the values of its members), environment (e.g., expansion into a new market), technology (e.g., the process used to transform inputs into outputs), or its strategy (including its mission and vision). In short, change can involve anything that happens within organizations. Managing change is an integral part of every manager’s job. How to best manage change is determined in part by what needs to be changed, and what type of change is needed. Figure 13.1 identifies three basic dimensions of change—scope, preparedness, and source—which combine to yield eight specific types of change.

Figure 13.1. A 3×2 table that shows eight types of organizational change

13.2.1. Scope of Change: Transformational versus Incremental

The scope of a change can be either transformational or incremental.[14] In simple terms, a transformational change occurs when an organization shifts from one type of organizational design to another,[15] while incremental change occurs when an existing organization design is fine-tuned.[16] Transformational changes are more difficult to manage than incremental changes. Organizations spend most of the time in periods of equilibrium characterized by incremental changes that fine-tune an existing organizational design type; these periods of equilibrium are occasionally interrupted or “punctuated” by bursts of transformational change when an existing organizational design type is replaced with a new one.[17] For example, Interface Inc. was an FBL defender prior to 1994, underwent a transformational change to become a TBL prospector by 1999, and then underwent another transformational change to become a SET analyzer by 2012.

Research suggests that organizations generally operate within a specific organization design for anywhere from five to thirteen years, during which time managers fine-tune the elements of that design. After this period of equilibrium, many organizations will (again) face internal and/or external pressures forcing them to abandon their existing organization design and adopt a new one.[18] This transformational change might be triggered when the CEO decides to address negative socio-ecological externalities, as Ray Anderson did in 1994. Or it might occur when a formerly stable environment suddenly becomes dynamic (e.g., when climate change threatens predictable weather patterns),[19] or when a new technology is developed that renders a current technology obsolete (e.g., when jet engines replaced propeller engines, or when the internet replaced regular mail). Because separate elements of the design may change independently and pull the organization in different directions, “misfit” is inevitable (that is, proper fit is compromised), and the tensions can only be resolved via transformational change.[20]

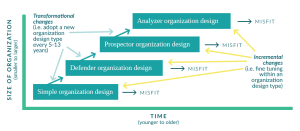

A helpful and common way to think about this ongoing back-and-forth between incremental and transformational change is captured by organizational life cycle theory. Organizational life cycle theory explains how organizations, as they grow in age and size, move in a predictable progression from one generic organizational design type to another.[21] This theory is built on the metaphor that just as humans go through a predictable life cycle (from childhood to youth to adult to old age), so also organizations go progress through a cycle of the design types described in Chapter 11, proceeding from simple to defender to prospector to analyzer. A variation of life cycle theory, which is clearly a simplified description of the change process, is depicted in Figure 13.2.[22]

Figure 13.2. Organizational life cycle, showing transformational versus incremental changes

Recall from earlier chapters that entrepreneurs typically launch new organizations as organically structured simple types that offer new products and services. As the simple organization grows in size, its operations become more established via a series of incremental changes that help to manage recurring environmental uncertainties. At the same time its technology becomes clearer and more analyzable, and its culture increasingly values predictability. Soon, managers are pushed to develop mechanistic administrative structures to accommodate its growth. In short, the simple organization is facing pressures to become a defender organization. Managers who are unable to bring this transition to fruition will find that their organization is stuck somewhere between a simple and a defender organization. In such a case it becomes an “administration-less misfit,” where the different elements of the organization’s design no longer fit together to form a coherent whole. This misfit can be resolved by adopting a defender organization design.

Similarly, a defender organization may enjoy success for many years of incremental change, but it inevitably becomes a “stifled misfit” unless it manages the transition to become a prospector type. For example, an FBL stifled misfit is one where the culture becomes so predictable and internally focused, where decision-making is so concentrated at the top of the hierarchy, specialization so narrow and standardization so prescribed, that members’ creativity is stifled and the organization fails to respond to the changing needs of its customers. This can be resolved by becoming a prospector organization.

Along the same lines, prospector organizations are vulnerable to becoming “scattered misfits,” where diffused decision-making authority and a lack of standardization across departments leads to failure. From an organizational life cycle perspective, a prospector can avoid failure by becoming an analyzer organization.

Finally, the analyzer organization can become a “stressed-out misfit” because the ambiguity and tension that comes from pursuing a dual strategy may lead to psychological stress and a difficulty to cope among members. What happens after the analyzer phase? An organization may be subdivided into many smaller (simple) units and/or be “re-born” as a variation of one of the earlier types.

13.2.2. Preparedness: Proactive versus Reactive

Change can also vary in terms of the preparedness of its managers.[23] When managers are on top of things and are effectively monitoring the fit (or lack of fit) among the key elements of their organization’s design (e.g., being aware of whether organizational structure and culture is aligned with changes in the environment or technology), then they can design and implement planned, proactive changes. Proactive change is designed and implemented in an orderly and timely fashion. Proactive change often occurs when managers see an opportunity to improve an organization’s performance. When members perceive opportunities for change, they increase their support for change and decrease their support for the status quo.[24] Interface’s changes in the opening case were planned, proactive changes.

In contrast, reactive change involves making ad hoc or piece-meal responses to unanticipated events or crises as they occur. Reactive change is often prompted by an unexpected threat facing the organization. A common problem faced by organizations is the failure of managers to anticipate or respond to changing circumstances; they are then forced to make unplanned, reactive changes. Sometimes reactive changes happen almost by accident without deliberate awareness on the part of managers, as an organization drifts from one way of doing things to another way. Reactive incremental changes rarely threaten an organization’s survival unless a firm finds itself unable to get itself out of a misfit stage. The danger of organizational failure is much greater in the event of unplanned reactive transformational change attempts, such as those prompted by the need to respond quickly to unexpected strategic initiatives by competitors.[25]

13.2.3. The Source of Change: Innovation versus Imitation

A third dimension of change is whether it arises from innovation within the organization or from imitating what other organizations are doing. Innovation involves the development and implementation of new ideas and practices. Innovation was evident when Interface developed a new kind of nylon that could be reused indefinitely to manufacture carpets. Imitation involves the application of existing ideas, which may come from other units within the organization or from outside of the organization. Imitation was evident when Interface provided its nylon technology to other organizations in order to reduce the industry’s overall negative externalities. Because imitative changes have a proven track record, they may be easier to manage and implement than innovative changes.

As depicted in Figure 13.1, eight types of organizational change arise from these three basic change dimensions (scope, preparedness, and source). This chapter will focus on changes that are transformational, proactive, and innovative because they are the most comprehensive examples of the change process.[26] Transformational changes are more encompassing than incremental changes, innovative changes are more challenging than imitative changes, and proactive changes provide a more complete picture of the four-phase change process than reactive change.

Test Your Knowledge

13.3. The Four-Phase Organizational Change Process

The most popular and influential contemporary models of organizational change have four phases: (1) recognizing the need or opportunity for change; (2) deliberately preparing for the change process; (3) making the change; and (4) safeguarding the change.[27] This four-phase process can be helpful for understanding all types of organizational change, but its full implications are most evident in changes that are proactive, innovative, and transformational. The first two phases would be much less well developed in unplanned, reactive changes.[28]

As depicted in the summary table at the beginning of this chapter, there is important variation but also considerable overlap among the three management approaches regarding the change process. FBL management is based on the classic idea that organizations seek to spend most of their time in periods of equilibrium, where all the elements of an organization’s design form a coherent whole that enables it to maximize efficiency, productivity, and financial well-being. In order to avoid their organization becoming a misfit, managers must occasionally make transformational changes where they “unfreeze” an existing configuration, implement changes, and then “refreeze” the organization until it is time to change again.

TBL management is similar, except that it seeks organizational design types that enhance profits by reducing negative socio-ecological externalities. Also, in contrast to the top-down approach of FBL management, the TBL approach seeks to involve members in the unfreeze–change-refreeze process, and on understanding the dynamic way that organizational design elements fit together.[29]

In SET management, thanks to its emphasis on participation and experimentation, there is more fluidity within each of the organizational design configurations than in either the FBL or TBL approaches. In the SET approach, it is advisable to occasionally “freeze” the action to see what is going on to determine whether change is called for.[30] Think of it this way: SET management sees an organization as if it were a movie of a particular genre (e.g., a comedy, drama, or mystery), and considers it important to occasionally press the pause button to see whether a change should be made (e.g., to the script, genre, characters) before pressing play again.[31] In contrast, both FBL and TBL management approaches are more likely to see an organization as a series of photos, where one photo captures how all the elements of its design are arranged in one era, and a second photo captures how the elements could be or have been rearranged after a transformational change and a new era has begun.

13.3.1. Phase 1: Recognize the Need and/or Opportunity for Change

To identify opportunities for change, managers rely on a variety of sources, including organizational members, customers, suppliers, formal information systems that monitor internal operations and the larger industry, and intuition that comes from having a deep understanding of existing operations. Change may be triggered by a wide variety of factors, such as depletion of affordable raw materials that the company relies upon as inputs (e.g., coal and oil for energy companies), opportunities to reduce negative socio-ecological externalities (e.g., reduce income inequality), or a lack of employees with specific skills (e.g., not enough nurses in a hospital). Or an organization may need to respond to new government regulations (e.g., affirmative action programs, pollution regulations) or new directives from shareholders (e.g., greater transparency about the compensation packages of senior managers). Finally, organizations may need to respond to technological innovations by competitors or suppliers. Note that the same trigger event may prompt different reactions among managers. For example, in response to ecological concerns, some managers may embrace clean technology, while others may see a short-term cost advantage in sticking with older, less environmentally friendly technologies. When Ray Anderson wanted Interface to invest in a solar array, the accountant said he couldn’t find a business case to support this decision; they did it anyway and it was a success, thanks to new customers attracted to the idea of solar carpets.[32]

Recognizing and responding to the need for transformational change often comes too late, resulting in misfit and eventually organizational failure.[33] This delay may be due to the natural human tendency to exhibit a threat-rigidity response where people who face a crisis, whether as individuals or in groups, tend to revert to familiar patterns of behavior that they perceive to have been successful in the past.[34] Sometimes reverting to past organizational designs is advisable, but sometimes it merely hastens the organization’s demise, especially if the past design is partly responsible for the current crisis.

Other factors that make it less likely that managers will recognize the need for change were discussed in Chapter 7. These include escalation of commitment (persevering in the current way of doing things because they do not want to admit that their prior decisions were ill-advised), information distortion (the tendency to downplay information that suggests you are doing something wrong), and administrative inertia (when existing ways of organizing persist simply because they are already in place). These factors all increase the likelihood of organizational failure, which comes when managers wait until the demise of an organization is imminent before beginning the costly and time-consuming transformational change process.[35]

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to the Need or Opportunity for Change

FBL management is distinct from TBL and SET approaches in two important ways. First, FBL management concentrates on looking for or recognizing needs and/or opportunities for changes that will help to maximize efficiency, productivity, competitiveness, and financial well-being, and does so without proactively pursuing opportunities to reduce negative socio-ecological externalities. Second, FBL management typically assumes that it is the manager’s job to identify opportunities and threats, and the manager’s job to develop the plan or vision regarding how to deal with these opportunities and threats.

In contrast to FBL managers, TBL managers seek to enhance financial well-being by proactively addressing negative socio-ecological externalities. Like FBL managers, TBL managers also draw on their experience and unique organizational vantage point to identify areas that could be changed. But unlike FBL managers, for whom identifying areas for change is a top-down process, TBL managers are more likely to involve organizational members to jointly diagnose the information and ideas that might prompt change. In this way, TBL management emphasizes participation and openness, which invites more members to become sensitized to the broader issues of concern for the organization and its stakeholders.[36] Managers at Interface Inc. spent four years discussing and developing a rich understanding of the needs and opportunities associated with enhancing socio-ecological well-being.

SET management, finally, has less need to maximize financial well-being than FBL and TBL approaches do, and therefore SET managers have freedom to consider a wider variety of changes that enhance socio-ecological well-being. SET management is also more likely to invite even broader participation in recognizing opportunities and the need for change, and in the merit of pressing the pause button (e.g., by paying close attention to the ecological environment). In particular, SET management is sensitive to the dignity needs of the least privileged in society, whether they are income-insecure people in the Philippines or around the world (e.g., MAD Travel, Chapter 6) or the underpaid cocoa farmers in Ghana (Divine Chocolate, Chapter 2).[37]

13.3.2. Phase 2: Prepare for Change

Once it has been established that there is a need for change (phase 1), one might expect that it should be easy to get everyone in the organization to be ready to hop on board. While this is sometimes true for incremental changes, it is often not true for transformational changes. Only about 25 percent of attempted transformational changes are successfully implemented.[38] An important reason that change attempts fail is because of inadequate preparation prior to actually implementing the change. Preparing for change involves using influence tactics to get organizational members to be open and willing to change.[39]

Change can evoke a wide range of emotions from the people facing or experiencing it. The very nature of organizational change creates stress, regardless of whether the change is perceived to be in someone’s interests (e.g., stress can be caused by being promoted or demoted). Change increases members’ exposure to uncertainty, disrupts informal support networks, and affects organizational structures and power.[40] Taken together, change may take a heavy toll on participants even when it is in the best interest of all organizational stakeholders.

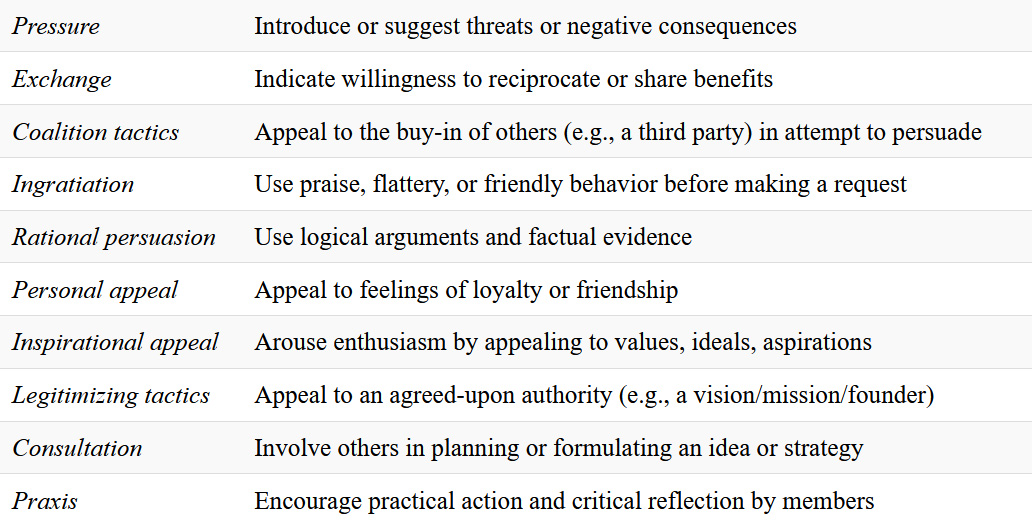

As shown in Table 13.1, managers can draw on a variety of influence tactics to prepare members for change.[41] Which tactics are used depends on which management approach is being used and whether managers seek to push members to change (e.g., by drawing attention to a crisis) or pull them (e.g., by drawing attention to an opportunity). Often a push-pull process works best, which reinforces the need for change (even though this may contribute to a threat-rigidity response) and then offers an enticing vision of what that change might look like (which helps to overcome the threat-rigidity response).

Table 13.1. Influence tactics to prepare members for change

Drawing attention to a crisis may include presenting members with alarming information and the potential negative consequences that might occur if they don’t change. This might involve using pressure tactics (e.g., pointing to the possible negative consequences of a crisis) or rational persuasion (e.g., using a graph to show a decline in sales, and another graph that links declining sales to job loss). By contrast, drawing attention to opportunities includes suggesting that organizational members will be better off if they change. This could involve rational persuasion (e.g., explaining how removing one product line and replacing it with another is in keeping with changes in market demands) or inspirational appeal (e.g., explaining how a new product line is in keeping with the organization’s vision).

However, even if members recognize the crisis and/or opportunity that is prompting a change, and even if their uncertainty is reduced by managers spelling out a clear vision of the future, members still might resist the change if they feel the change is a violation of their psychological contract. A psychological contract is an unwritten expectation related to the exchanges between an employee and the organization.[42] For example, an employee might feel their psychological contract has been violated when they are required to do more or different work, thus raising the objection that “I wasn’t hired for this.” To address this, managers may use influence tactics like exchange (e.g., offering higher pay for the increased work effort), or personal or inspirational appeal (e.g., asking members to increase their efforts for the sake of the greater good).[43]

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Preparing for Change

More than TBL and SET approaches, an FBL approach tends to assume that managers and experts will play the primary role in identifying and planning the change, and that managers will then use influence tactics to prepare members to accept the change. FBL managers explain or interpret the need and vision for change to members, and try to convince members of the merit of the manager’s insight and plans for the change. The emphasis is on getting other members to “buy into” the ideas that management is promoting, and FBL managers are more likely to use instrumental exchange, pressure, and coalition tactics than TBL and SET managers.

In contrast, TBL management is more likely to use consultation and inspirational tactics to invite members to participate in developing the vision for the change. This creates a powerful sense of ownership and commitment, and this emphasis on consultation was already evident in phase 1, where members participate in recognizing the need for change. Such bottom-up involvement is more likely to lead naturally to a shared vision.[44] By allowing people to share in the process of gathering and assimilating information, the vision becomes theirs.[45]

Involving members in establishing the vision of an organization not only allows TBL management to empower members, it also allows managers to access the knowledge of frontline members to help redesign how the organization works. Of course, management and staff experts also bring knowledge that other members do not have. Even though having management and members working together will result in a better vision and a more effective organization, historically such consultation and partnership has not happened as often as one might think. Why? First, managers often believe that empowering others dilutes their own power, even though sharing control can actually empower both parties.[46] Second, in the past organizations were smaller and technologies were less complex, so that members did not have as much unique valuable information to contribute and the extra time that was required to access this knowledge was deemed inefficient. Third, managers expect that members will be unlikely to suggest changes to enhance the financial well-being of owners if that could threaten their own self-interests.

TBL management recognizes that many things have changed over the years. Today members have important knowledge to bring to the table, and they are motivated to create visions and organization designs that help to improve socio-ecological well-being. TBL management recognizes that both members and owners want their organization to become a better place, and in return members have less reason to fear that management will take advantage of them. When a crisis or opportunity is recognized, members have a standing invitation to help develop a win-win solution. By being informed and involved in the change process, members are more likely to accept even those changes that may not be in their own material self-interest but which do enhance overall economic and socio-ecological well-being.

SET management differs from the other two approaches in its ongoing practice of inviting members to test out new approaches that address the needs established in phase 1. This is consistent with SET management’s emphasis on experimentation, as described in Chapter 10, and extends it to issues that may inform an organization’s mission or vision. For SET management, such experimentation refers to practical actions, that is, actual changes that address the problem (see also trial and error decision-making, Chapter 7). This emphasis on praxis is reinforced by SET management’s collaborative inquiry approach,[47] which uses consultation and inspirational tactics to invite members to participate in developing the vision for the change.

The experiments in SET management differ from the experiments under FBL or TBL management in several significant ways. First, FBL and TBL approaches tend to emphasize “thought experiments,” where employees are asked to envision the future, or to imagine what their jobs will be like after a specific change has been implemented. In contrast, SET experiments involve hands-on, practical activities. Second, even when FBL and TBL managers do introduce hands-on experiments—for example, Interface was already introducing pilot projects and creating “small wins” prior to phase 3 in the change process—they are not as likely as SET managers to authorize members themselves design and carry out the experiments, or allow members to opt out of certain experiments.

To illustrate the SET approach, consider the example of Robert Greenleaf, a corporate vice-president at AT&T, who became aware that women were under-represented among the work crews who installed telephone lines.[48] When he met with operations managers to draw their attention to this issue (phase 1), Greenleaf very consciously adopted a “we” attitude, deliberately reminding himself that he was part of the culture and organizational practices that were associated with this problem. Then he asked the operations managers to help identify the problematic behavior in light of the “potential biases within ‘our’ embedded tradition system.” In effect, he was pressing the pause button and asking members to evaluate and critically reflect upon why women were under-represented in their workforce. Some operations managers responded by saying that a major reason might be because workers had to regularly lift rolls of telephone cable that were 50 pounds (almost 23 kilograms), which they felt were too heavy for most women to lift on a sustained basis. Someone suggested having their supplier provide 25-pound rolls (about 11.3 kilograms). This ushered in phase 2 of the change process, when Greenleaf used his authority to have the supplier provide 25-pound rolls for any operations managers who wanted to experiment with this idea (some managers were adamantly opposed). The experiment showed that women were fine with regularly lifting 25 pounds, and that the men preferred it too! These experiences ushered in phase 3, where managers began thinking differently about their unit’s work, and soon this change was made voluntarily throughout the company (phase 4).[49]

SET management’s focus on practical action in phase 2 (prepare for change) is consistent with the Aristotelian idea of praxis. Praxis is a combination of critical reflection and practical action that facilitates positive change.[50] Critical reflection ensures that members are engaged and thinking about their firm’s positive and negative externalities, while practical action increases the likelihood that members will change their views about how their organization should work. The merits of praxis are illustrated by research that shows, for example, that even though many people recognize the need to make changes in order to combat climate change, this knowledge on its own does not change their worldview or behavior. However, people do change become more ecologically minded, less materialistic, and less individualistic) after doing and reflecting upon a one-week “experiment with sustainability” (e.g., not using fossil fuels, not eating meat).[51]

Overall, research shows that change is facilitated when there is room in organizations for building interpersonal relationships where trust and collaboration can develop (relational spaces), allowing new ideas and understanding to emerge (conceptual spaces, related to phase 1 of the change process), and novel approaches can be tested (experimental spaces, related to phase 2).[52]

Test Your Knowledge

13.3.3. Phase 3: Make the Change

This is the phase where key changes are implemented. For incremental changes—which do not need as much effort in navigating phases 1 and 2—this serves to fine-tune an organization’s structure, technology, or strategy. Transformational changes include these elements as well as the idea of the how they fit together to make a sensible whole. This often involves (re)formulating and implementing strategy (Chapters 8 and 9) and rethinking organization design (Chapter 11).

Phase 3 is often where the role of managers is the most visible. Although change agents are important throughout all four phases of change, during this phase it is critical that change agents model appropriate behavior and provide visible support for the initiative. A change agent is someone who acts as a catalyst and takes leadership and responsibility for managing part of the change process. Change agents are often managers or human resource specialists from within the organization. Or a change agent may be an outside consultant. Change agents make things happen, and a part of every manager’s job is to act as a change agent in the work setting (see the entrepreneur role from Mintzberg’s study, Chapter 1).

Change agents sometimes work in conjunction with idea champions. An idea champion is a person who actively and enthusiastically supports a new idea. Change agents and idea champions work collaboratively to promote change within the organization by building support, overcoming resistance, and ensuring that innovations are implemented.[53] The roles of change agents and idea champions differ for FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Making the Change

In this phase, the FBL approach emphasizes the use of managerial authority to ensure that organizational members understand and know how to implement the technical aspects of a change and are committed to implementing it. While it may be easy to convey these aspects of a change, it can be challenging to achieve commitment.[54] Even if phases 1 and 2 have been completed successfully, the change process can still fail in phase 3. It is not enough for managers to develop a technically brilliant vision for a change. Managers also need human relations skills to make sure members implement the change. When change attempts fail, 80 percent of the time members attribute this to managers: particularly those lacking adequate communication skills and practices, and displaying poor work relationships and poor interpersonal skills.[55] A manager lacking these skills leaves members uncertain and stressed, and also fails to provide access to the rich informal knowledge that exists in an organization. Other important factors include managers failing to set clear goals, breakdowns in delegating authority to others, and an inability to break old habits (each mentioned about 60 percent of the time).

An FBL approach points to three things a manager can do to increase members’ commitment to change. First, a manager should increase members’ confidence in the manager by establishing their own credibility, acquiring appropriate skills, leading by example, being well-prepared, and not overreacting to drawbacks.[56] Second, a manager should increase members’ self-confidence by clarifying expectations, providing training,[57] planning for early success,[58] and providing necessary resources.[59] Third, a manager should encourage members to adopt a positive attitude about the change by communicating the intrinsic benefits of the change (e.g., enhancing job security),[60] linking it to extrinsic rewards such as pay raises and bonuses, and hiring and promoting members who have a positive attitude toward the change.[61]

In a TBL approach—unlike the FBL approach, where managers typically rely on their hierarchical authority to develop a change and describe how it is to be implemented—managers couple their authority with continued attention to members’ participation, as in phases 1 and 2. They do this by providing forums for open discussion, and by providing resources and recognition for change agents and idea champions.[62]

Elaborating on this, the TBL approach points to at least three strategies managers can take to improve members’ commitment to change. First, in order to increase confidence in the manager, the manager should continue to foster members’ participation in the change process (as they did in phases 1 and 2) and be trustworthy (including demonstrating a willingness to put members’ well-being ahead of the manager’s own personal interests).[63] When managers share power, members are more likely to commit to change because they have greater confidence that the manager is doing what is best for the organization.[64] In addition, enhancing participation and teamwork contributes to personal satisfaction as well as to improving productivity and performance.[65]

Second, in order to increase members’ self-confidence, managers should foster opportunities for informal and peer learning. Like FBL management, TBL management also recognizes the benefit of training and clear expectations in building confidence. However, TBL managers are more likely to create spaces or opportunities for informal or peer learning to enhance the skills of employees and to provide relevant information. Instead of tightly controlling and delivering training and information, TBL managers create and nurture an environment where members can learn from each other. This does not mean that managers leave communication and change to chance. TBL managers are aware of their role in helping others make sense of what is happening in the organization as change brings about intended and unintended outcomes.[66] That is, managers must be able to pick up on issues that have the potential to discourage or to create dissension throughout the organization.

Third, in order to encourage members to have a positive attitude toward change, TBL managers should encourage communication about the benefits (and sacrifices) of the change, as will happen when working through the above.

The SET approach emphasizes similar skills and behaviors as FBL and especially TBL approaches, but SET management is significantly different from FBL and TBL management in this third stage of the change process. Whereas FBL and TBL management focus on implementing a desired change in what things are done, SET management also understands the importance of how members understand and think about their jobs and about how their organization works, or why things are done. In particular, SET management looks for changes in members’ ways of thinking and understanding their work that result from their praxis experiments that were started in the second phase of the change process.[67] The key change is for members to see their work world differently, to interpret their jobs through a new lens, and to relabel the components of their work. Of course, the changes to what things are done as a result of experiments are important, as they represent how the elements in an organization are being rearranged in a tangible way. But it is the change in seeing the organization and its elements differently that is key for SET management. In the example of Robert Greenleaf at AT&T, change happened when operations managers started to see that women were legitimate hires, that women could do the job as well as men, and that everyone felt better about their organization when women were treated as equals. This was not a compromised worldview that members reluctantly accepted; instead, this had become a new worldview that members were excited to have developed via praxis. Because of this changed worldview, the organizational change was more likely to be safeguarded going forward (phase 4).

Another distinction is that SET management is more likely to involve external stakeholders in the change process. Simply being mindful of other stakeholders can already have an effect. For example, former Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos sometimes left an empty chair around the table at a meeting and asked attendees to imagine that the seat was filled by a customer, “the most important person in the meeting.”[68] SET managers may be especially inclined to have voice-less stakeholders seated in the empty chair, such as the natural environment, or future generations, or someone from the local community who is homeless. Hearing directly from a variety of external stakeholders—especially those from the margins—can be even more more powerful and lead in unexpected directions and yield counter-intuitive corporate decisions (such as when Interface decided to build a solar array even though it lacked a business case to do so). Such participation deepens participants’ understanding of existing relationships and systems because it draws on the experience and knowledge of a wide variety of stakeholders. This broad participation also informs the implementation of changes so that changes more fully consider the complexity of the system.

Test Your Knowledge

13.3.4. Phase 4: Safeguard the Change

Once a change has been implemented, steps must be taken to ensure that the change is reinforced (i.e., becomes institutionalized), and that organizational practices do not revert to previous ways. Ideally, the change becomes second nature to members because it is embedded in their everyday actions and thoughts. This involves creating structures that reinforce the change, and dismantling structures and systems that undermine it.

FBL, TBL, and SET Approaches to Safeguarding the Change

In FBL management this phase is called refreezing, and FBL managers use a top-down approach to fine-tune various aspects of the organization to reinforce the change implemented in phase 3. This may involve fine-tuning the fundamentals of how work is organized (e.g., standardization, specialization, and centralization) and who reports to whom (departmentalization). It also requires revising formal job descriptions, aligning the performance appraisal and reward systems with the new expectations, and adapting recruitment and promotion practices to reinforce the new culture. The idea is to reestablish the organization’s structures and systems so that the new ways of doing things are repeated and rewarded (for more on the importance of rewards, see Chapter 14).[69]

TBL management also seeks to ensure that positive changes remain implemented throughout the organization.[70] But unlike FBL managers, who seek to re-freeze the changed organization via formal structures and systems, TBL managers are more likely to want to re-slush the organization because, like SET managers, they expect some ongoing experimentation within the organization. Thus, TBL managers make changes to structures and systems (such as adjusting misaligned reward systems) with an eye to ensuring the changes foster subsequent learning and flexibility. An important part of TBL management is that ongoing member-initiated improvements are acknowledged, celebrated, and diffused throughout the organization as appropriate. “Slushing” also assumes that a change may not work uniformly well throughout the organization.

In SET management the final phase is called resuming, which goes even further from the FBL practice of freezing than the TBL preference for re-slushing. SET management expects and encourages its members to maintain dynamic relationships between organizational design elements and various stakeholders. Returning to the metaphor of a movie, once the pause button has been pressed (phase 1), and the cast and directors have had a chance to experiment with new scripts (phase 2) and reflect on them in a way that changes their worldview (phase 3), everything is ready for the play button to be pressed and the action to resume. In this metaphor, SET movie directors place greater importance on improvisation than on rehearsing prescribed lines and repeatedly shooting the same scene to get it exactly as written in the script. For example, recall that employees at Semco do not even keep minutes during their meetings, because the goal is for members to remain flexible going forward (Chapter 10). SET management encourages flexible structures that can support continuous change. This includes monitoring the outcomes of ongoing experimental changes and providing opportunities to share these successes with others in order to promote further learning. Positive changes are celebrated and disseminated to provide examples for others to consider and adopt (such as when all the units in AT&T started using 25-pound rolls of cable). Ultimately, changes that begin and grow informally may become institutionalized throughout the organization via a bottom-up process (not decided top-down by management).

Test Your Knowledge

13.4. Intrapreneurship

In each chapter we have considered how the tools and ideas introduced apply to entrepreneurs, and we have primarily focused on classic entrepreneurs (those starting a new organization). However, the issues of organizational change discussed in this chapter are not as relevant to the concerns of an entrepreneurial start-up. In a new organization, there are few routines and little history; there are no institutionalized “old ways” to hold on to, and current practices may have been developed literally yesterday. Dynamism and change are taken for granted in start-ups, and thus often provoke less resistance.

However, the sorts of change discussed in this chapter, especially planned, transformational, and innovative changes, are of considerable importance to intrapreneurs—those who pursue entrepreneurship within an existing organization. In this section we therefore consider how the tools from this and previous chapters can be integrated with the four phases of the change process to help intrapreneurs introduce new ventures within existing organizations.

13.4.1. Phase 1: Recognize the Need or Opportunity for Change

Intrapreneurial initiatives are often instances of proactive, innovative, and transformational organizational change. Thus, the first step in the change process is akin to the first step in the entrepreneurial process, except in the latter it is to identify an intrapreneurial opportunity. A key difference, though, is that an intrapreneur has access to a host of existing organizational resources to start a new venture, whereas the classic entrepreneur starts with more of a blank slate. The intrapreneur thus begins with significant advantages (e.g., access to funds, expertise, and collaborators to identify opportunities and challenges[71]), as well as added challenges (needing to change what an existing organization does).

The kinds of opportunities intrapreneurs identify will vary by management type. FBL intrapreneurs are likely to focus on opportunities where they can leverage existing resources to increase financial returns (e.g., reducing costs by outsourcing manufacturing to overseas factories). TBL intrapreneurs will look for opportunities where they can leverage existing resources to address social or ecological issues (e.g., finding ways to profitably offer their products in low-income countries, to permit people at the Base of the Pyramid to participate in and enjoy the fruits of belonging to a global economy[72]). SET entrepreneurs may seek to change fundamental ways an organization produces its goods and services (e.g., Ray Anderson acted like an intrapreneur when he recognized the need for Interface to transform its ecologically irresponsible practices). SET intrapreneurs often employ management action research (MAR) approaches, which involve reflection practice, engagement practice, and dissemination practice to identify and address fundamental organizational changes.[73]

Regardless of whether they follow an FBL, TBL, or SET approach, once intrapreneurs have identified an opportunity for change, they can use the same strategic management tools used by other managers within their organization (and used by classic entrepreneurs). This includes developing stakeholder maps, performing SWOT analyses (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats), identifying an appropriate generic strategy, and crafting a vision and/or mission statement for the new initiative, whether this is driven by the intrapreneur working independently (FBL approach), with members (TBL approach), or with a range of stakeholders (SET approach). Having a clear and compelling value proposition for the intrapreneurial change will increase access to organizational resources and reduce resistance.

13.4.2. Phase 2: Prepare for Change

Unlike classic entrepreneurs, who focus only on preparing for their new start-up vis-à-vis the larger market, intrapreneurs must in addition prepare their host organization for the intrapreneurial initiative. As described in the chapter, the process of preparing for change will differ for FBL, TBL, and SET entrepreneurs.

In particular, because intrapreneurs are working within an existing organization, they must consider market cannibalization, an issue that most classic entrepreneurs do not have to deal with. Market cannibalization refers to the negative effect that a new product or service has on an organization’s existing products and services. For example, imagine that an airline company launches a new discount subsidiary offering flights with fewer services, in smaller planes, and at cheaper prices. In this situation, it is likely that some travelers who would otherwise have chosen the main airline will instead choose a discount fare. This loss of a full-fare customer represents cannibalization and is an issue that intrapreneurs need to consider. Another example might a company that supplements its regular products by introducing a “green” product line, which then draws customers away from its traditional products.[74] Cannibalization is most common in mature industries that are not growing, because there are few truly new customers. Some organizations practice intentional cannibalization (e.g., manufacturers wanting consumers to upgrade their phones or computers to the latest model), but the possibility for loss makes it essential that intrapreneurs conduct a thorough analysis of the environment and industry, as well as consider the place of the new venture in the organization’s overall corporate strategy.

Unless they are envisioning the creation of product categories that are unrelated to their firm’s existing offerings, FBL intrapreneurs will be most concerned about negative effects from cannibalization, as the FBL model generally assumes a relatively fixed market filled with self-serving and price-conscious customers. Any new product or service must be carefully assessed for its potential to reduce financial returns.

In contrast, some amount of cannibalization is likely to be built into TBL intrapreneurship; it may even be the goal. New initiatives within the TBL approach typically involve changing an old product or process to increase profits by being more sustainable. As such, if the new product is more profitable or offers more benefits in terms of public image and brand loyalty, the TBL organization would prefer to have their customers switch to it.[75]

SET intrapreneurs will usually be the least concerned about cannibalization. Indeed, few SET markets are mature; because the world’s socio-ecological problems are large and complex, there is room for growth. Likewise, since the SET approach is less focused on maximizing financial profit, having customers change from one product to another is less problematic, as long as the organization remains viable and/or the goals of socio-ecological well-being are enhanced. In fact, many SET organizations would love to become obsolete. Mohammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank that provides microfinancing to impoverished entrepreneurs, is known for saying that our grandchildren will need to go to a museum to see poverty.[76]

13.4.3. Phase 3: Make the Change

Both when preparing for and implementing their initiative, intrapreneurs need to be particularly attuned to issues related to organizational (re)design. Whereas classic entrepreneurs struggle with the work required to start up a fully developed organization design, intrapreneurs must find their place within an existing organization design. If the intrapreneurial initiative is to succeed, it will likely need to make changes to the host organization’s culture and structure.

In particular, when working within host organizations that have relatively rigid organizational designs—often typical of the mature existing organizations that can best afford to support an intrapreneurial venture and may have the most to gain by its infusion of new ideas—intrapreneurs will be pushing for more fluidity and room to experiment. However, when working within host organizations that have more dynamic organizational designs—where experimentation and ideas for potential new initiatives are commonplace—intrapreneurs may be pushing for greater rigidity as they promote a specific idea for which they need firmly committed organizational resources. This is part of the reason that the manager’s role in a change is often the most visible in phase 3—it is managers that have the authority to commit resources. Thus intrapreneurs must engage in both top-down and bottom-up change processes, building strategic support while eliciting participation from below.[77]

13.4.4. Phase 4: Safeguard the Change

Having implemented their initiative, intrapreneurs must ensure that it becomes institutionalized so that practices do not revert to the way they were before. If the intrapreneurial initiative was transformational in scope, then the whole organizational design may need to be adjusted. But even if the initiative was smaller (e.g., launching a new product, or changing how an internal process operates), the change still needs to be integrated with established procedures. Think of the number of people you know who have made New Year’s resolutions or other promises to change their behavior (e.g., lose weight, stop smoking, sleep more, stop using social media), but then a few weeks or months later return to their previous behavior. Similar processes are at work in organizations, which is why phase 4 is so important.

Unlike classic serial entrepreneurs, who are often most adept at the start-up phase but not particularly comfortable with developing and managing the ongoing structures and systems associated with mature and stable organizations, intrapreneurs are often more at home in developing the structures and systems required to safeguard the intrapreneurial venture (e.g., compare Larry Mauws and Michael Mauws of Westward Industries, Chapter 18). Intrapreneurs are relatively comfortable in this phase because it involves a return to “normal,” where normal means being part of an organization with well-developed systems and functions (Chapter 18). For those intrapreneurs who have successfully implemented their initiative within a fairly rigidly structured host organization, this may mean allowing the intrapreneurial venture to become more rigid over time. And for intrapreneurs who have successfully carried out their initiative within a host organization with a dynamic design, this may mean allowing the intrapreneurial venture to also be dynamic over time.

Test Your Knowledge

Chapter Summary

- Organizational change is complex and varies in its scope (transformational versus incremental change), preparedness (proactive versus reactive change), and source (innovative versus imitative change).

- The change process has four phases:

- (i) recognize the need and/or opportunity for change

- (ii) prepare for change

- (iii) make the change

- (iv) safeguard the change

- The four phases in the change process are managed differently in FBL, TBL, and SET approaches.

- FBL management has a top-down, productivity-maximizing financial focus, where managers

- (i) recognize the need and/or opportunity for change and develop the change vision

- (ii) use influence tactics to overcome resistance and persuade members to buy into the change

- (iii) use their authority to implement the change and gain commitment

- (iv) establish structures and systems to ensure the change remains entrenched

- TBL management has a bottom-up triple-bottom line bias, where managers

- (i) sensitize members to a wider scope of areas where change may be appropriate (not just changes that enhance financial well-being)

- (ii) involve members when developing the change vision

- (iii) work together with members to implement change and gain commitment

- (iv) encourage ongoing learning among members

- SET management has a bottom-up socio-ecological well-being bias, where managers<

- (i) press the pause button at times when heightened critical reflection is called for

- (ii) invite members to design and carry out experiments to address a problem and/or opportunity

- (iii) facilitate the ability and opportunity for members to change their worldview as they reflect upon their experiments

- (iv) encourage ongoing adaptive improvisation and learning among members

- FBL management has a top-down, productivity-maximizing financial focus, where managers

- The four-phase change process provides concepts and tools helpful to manage the intrapreneurial process, including how to work with and build on resources in an existing organization (e.g. opportunities for collaboration) and how to address the challenges of convincing an existing organization to move in a new direction (e.g., threat of cannibalization).

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

- Identify the four steps in the change process. What are the main differences between FBL, TBL, and SET approaches in each step?

- As an employee, which management approach—FBL, TBL, or SET—would you prefer to be in place when your organization is going through a change? If you were a manager, which approach would you prefer? Explain your reasoning.

- Think of an organization where you have worked. Which management approach to change—FBL, TBL, or SET—do you think would be the most effective in that organization? Think of a change that was introduced in this organization. What system was used? Was that system the one you think they should have used? Why or why not?

- Think of a change that has occurred in your life recently. How did you react to the change? Is the way you reacted similar to the way you react to change generally? Why or why not? What are things that make you more (and less) open to change?

- From your personal experience, what do you think are the three most important reasons that people resist change? What can be done to minimize resistance and increase commitment? How do your ideas compare with what this chapter says?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of including more stakeholders in shaping and implementing the change process?

- What changes might happen if your classrooms included an empty seat for homeless people from your community, or for the half the world that lives on less than ten dollars a day, or for Mother Earth?

- In previous chapters you have been developing an Entrepreneurial Start-Up Plan (ESUP) for an organization that you would like to create. You have probably been thinking of your organization as a new start-up, but how might it be possible to realize your value proposition within an existing organization via intrapreneurship? Identify a specific organization that you think would be well-suited to pursue your idea intrapreneurially. What do you think makes it suitable? What changes would the existing organization be required to make? What would need to be done to manage that process? Sketch out an intrapreneurial plan for achieving your ESUP goals within the existing organization you have identified.

- The opening case was drawn from Redekop, B. W. (2024). Sustainable leadership in business: The Ray Anderson solution. In Environmentally sustainable leadership (pp. 107–123). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800374058.00010; Rajala, R., Westerlund, M., & Lampikoski, T. (2016). Environmental sustainability in industrial manufacturing: Re-examining the greening of Interface’s business model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 115: 52–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.057 ; Dean, C. (2007, May 22). Executive on a mission: Saving the planet. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/22/science/earth/22ander.html ; Anderson, R. C. (1998). Mid-course correction: Toward a sustainable enterprise: The interface model. Peregrinzilla Press; Nature and the industrial enterprise: Mid-course correction: An interview with Ray C. Anderson. (2004). Engineering Enterprise (Spring): 6–12; Hawken, P., Lovins, A., & Lovins, L. H. (1999). Natural capitalism: Creating the next industrial revolution. Little, Brown and Company; Interface Inc. company website, at http://www.interfaceinc.com ↵

- Lampikoski, T. (2012). Green, innovative, and profitable: A case study of managerial capabilities at Interface Inc. Technology Innovation Management Review, 2(11): 4–12. https://www.timreview.ca/sites/default/files/article_PDF/Lampikoski_TIMReview_November2012.pdf; Stubbs, W., & Cocklin, C. (2008). An ecological modernist interpretation of sustainability: The case of Interface Inc. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(8): 512–523. Unless otherwise noted, all dollar amounts in this chapter are in US currency. ↵

- Rajala et al. (2016). ↵

- Havey, N. (Writer/Director). (2021) Beyond zero [Video trailer]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBAvYFor1zA ↵

- Quoted in Dean (2007). ↵

- Rajala et al. (2016: 56). ↵

- Rajala et al. (2016: 56). ↵

- Branson, R. (2013). Screw business as usual: Turning capitalism into a force for good. Penguin. ↵

- A new service Interface developed was to lease carpeting to industrial customers, so that Interface would take care of and replace carpet as needed. However, this leasing service failed because of government regulations that limited customers’ tax advantages. ↵

- Anderson links this soft side to the need for spirituality in business: “The growing field of spirituality (a term that, frankly, turned me off when I first heard it, because I associated it with religiosity) in business is a cornerstone of the next industrial revolution” (Anderson, 1998). ↵

- Stubbs, W., & Cocklin, C. (2008). An ecological modernist interpretation of sustainability: The case of Interface Inc. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(8): 512–523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bse.544 ↵

- Stubbs & Cocklin (2008). ↵

- Rajala et al. (2016: 58). ↵

- Van de Ven, A. H., & Poole, M. S. (1995). Explaining development and change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 20(3): 510–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/258786 ↵

- Kavanagh, M. H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2006). The impact of leadership and change management strategy on organizational culture and individual acceptance of change during a merger. British Journal of Management, 17(S1): S81–S103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00480.x ↵

- Burnes, B. (2019). The origins of Lewin’s three-step model of change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 56(1): 32–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886319892685 ↵

- Greiner, L. E. (1998). Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 76(3): 55–68. https://hbr.org/1998/05/evolution-and-revolution-as-organizations-grow; Haveman, H. A., Russo, M. V., & Meyer, A. D. (2001). Organizational environments in flux: The impact of regulatory punctuations on organizational domains, CEO succession, and performance. Organization Science, 12(3): 253–273. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247824208_Organizational_Environments_in_Flux ↵

- Research consistent with what has been called a “punctuated equilibrium” view suggests that organizations are usually in period of equilibrium (incrementally fine-tuning an existing organizational design type, which may last five or more years) but must occasionally experience a period of punctuation (a transformational change from one organization type to another). Organizations that fail to make qualitative changes to their organizational design risk becoming misfits and failing. For more studies in this area, see Dyck, B. (1997). Understanding configuration and transformation through a multiple rationalities approach. Journal of Management Studies, 34: 793–823; Greenwood, R., & Hinings, C. R. (1993). Understanding strategic change: The contribution of archetypes. Academy of Management Journal, 36: 1052–1081. https://doi.org/10.5465/256645; Hinings, C. R., & Greenwood, R. (1988). The dynamics of strategic change. Basil Blackwell; Romanelli, E., & Tushman, M. L. (1994). Organizational transformation as punctuated equilibrium: An empirical test. Academy of Management Journal, 37(5): 1141–1166. https://doi.org/10.2307/256669; Miller, D. (1992) The Icarus paradox. HarperCollins. ↵

- Yang, E., & DiBenigno, J. (2024). Opportunistic change during a punctuation: How and when the front lines can drive bursts of incremental change. Organization Science, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.15120 ↵

- The “misfit type” corresponds to what Miles and Snow (1978) called the “reactor” organization, which referred to organizations that lack consistency among the elements of their organization design. Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and process. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ↵

- Much has been written about organizational life cycle theory, but the classic article still is Greiner, L. E. (1972). Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 50 (July–August): 37–46; for an updated version with additional commentary by the author, see Greiner, L. E. (1998). Harvard Business Review (May–June). https://hbr.org/1998/05/evolution-and-revolution-as-organizations-grow. While organizational life cycle theory is too prescriptive, it does have an underlying truth that continues to make it attractive to and helpful for practitioners and students. And there is research that supports the basic contention that managers change their organizations from one type to another over time. The research suggests that organizations may spend from five to thirteen years in any one type (with some exceptions, like Lincoln Electric), but that as they outgrow it managers feel compelled to change (e.g., Dyck, 1997). Although life cycle theorists might argue that an organization that has grown out of the simple type must enter the defender type (no skipping of types is permitted), subsequent scholarship suggests that this is too rigid and we expect that managers will be able to choose to change into any one of the remaining types. ↵

- Note that these general arguments are consistent with life cycle theory, but that the particular names we give to each type of organization differs from the names used by Greiner (1972) while building on the descriptions used by Greiner (1972) and others, including page 353 in Dyck, B., & Neubert, M. (2010). Management: Current practices and new directions. Cengage/Houghton Mifflin. Our discussion elaborates life cycle thinking by using terms and concepts related to organization design as presented in Chapter 12. Of course, we fully recognize that our elaboration of the life cycle model in the first place already simplifies reality. ↵

- Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. (1990). Beyond the charismatic leader: Leadership and organizational change. California Management Review, 32(2): 77–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166606; Badawi, B., Nurudin, A., Muafi, M., & Salsabil, I. (2025). Readiness to change and dynamic capability for growing green competitive advantage of post-merger rural banks in Indonesia. Review of Integrative Business & Economics Research, 14(2): 198–212. https://buscompress.com/uploads/3/4/9/8/34980536/riber_14-2_14_s24-287_198-212.pdf ↵

- Dyck, B. (1996). The role of crises and opportunities in organizational change. Non-Profit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25(3): 321–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764096253004 ↵

- Dyck, B. (1990). A dynamic model of organizational failure. In J. M. Geringer (Ed.), Proceedings of Policy Division, 11(6): 35–44, Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Whistler, British Columbia. ↵

- Dyck, B., Mischke, G., Starke, F., & Mauws, M. (2005). Learning to build a car: An empirical investigation of organizational learning. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2): 387–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00501.x ↵

- Although the four-step description provided here is based on Lewin’s basic change model, it draws from and builds on a variety of studies, including the four-phase learning model developed by Mary Crossan et al. See Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. Tavistock; Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review, 24(3): 522–537. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/259140 ↵

- For example, Dyck et al. (2005). ↵

- The TBL approach described here builds on a number of other models in the literature, such as Beer, M., Eisenstat, R., & Spector, B. (1990). Why change programs don’t produce change. Harvard Business Review, 68(6): 158–166. https://hbr.org/1990/11/why-change-programs-dont-produce-change ↵

- SET management modifies and builds on the four-step friendly disentangling process used by Greenleaf. See Nielsen, R. P. (1998). Quaker foundations for Greenleaf’s servant-leadership and ‘friendly disentangling’ method. In L. C. Spears (Ed.), Insights on leadership (pp. 126–144). John Wiley & Sons; the four-phase virtuous circle described in Dyck, B., & Wong, K. (2010). Corporate spiritual disciplines and the quest for organizational virtue. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 7(1): 7–29; and ideas drawn from Weick, K. E., & Quinn, R. (1999). Organizational change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 50: 361–386. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.PSYCH.50.1.361; and Purser, R. & Petranker, J. (2005). Unfreezing the future: Exploring the dynamic of time in organizational change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(2): 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886304268157 ↵

- Although periods of equilibrium are thought of as relatively calm, in reality they have ongoing tensions and forces for transformational change that are not pursued. For example, see Dyck, B. (1997). Understanding configuration and transformation through a multiple rationalities approach. Journal of Management Studies, 34(5): 793–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00072 ↵

- Havey, N. (Writer/Director). (2021) Beyond zero, Clip 1. Havey Pro Cinema. https://beyondzerofilm.com ↵

- Dyck (1990). ↵

- Staw, B. M., Sandelands, L. E., & Dutton, J. E. (1981). Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: A multilevel analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(4): 501–524. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392337; Mazzei, M. J., DeBode, J., Gangloff, K. A., & Song, R. (2024). Old habits die hard: A review and assessment of the threat-rigidity literature. Journal of Management, 01492063241286493. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063241286493 ↵

- Dyck (1990). ↵

- Sometimes TBL and SET managers might educate members at all organizational levels in how to read financial statements and how to link their own actions to the organization’s health and well-being. An example of this approach is sometimes referred to as “open-book management,” which enables and invites all members of an organization to participate in identifying opportunities and needs to change. Jack Stack was an early pioneer in this approach to sharing information with employees: “It's amazing what you can come up with when you have no money, zero outside resources, and 119 people all depending on you for their jobs, their homes, even their prospects for dinner in the foreseeable future.” Stack and a handful of managers purchased their small manufacturing company from International Harvester when they were given the choice of either ownership or a shut down. The company was in a dire situation that could only be reversed with a radical approach that required employees to understand the business in a new way so that everyone could make decisions to keep the company afloat. With the combined wisdom of the whole company, they changed their company for the better. Open-book management is an ongoing approach to managing change. It holds as a core belief that significant change occurs when people at the bottom are meaningfully engaged and allowed to have a voice. Stack, J., & Burlingham, B. (1992). The great game of business. Doubleday. ↵