De-centering English with “language of the day” in undergraduate linguistics

This article is a reproduction of the following CC BY source.

Hauser, Ivy, Erica Dagar, and Emily Graham. 2024. De-Centering English With ‘language of the day’ in Undergraduate Linguistics. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 9 (3): 5850. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v9i3.5850.

Abstract

Undergraduate linguistics courses often prioritize data from prestige varieties of English. This limits student learning to test cases of English and centers prestige varieties in the linguistics educational experience. We developed a method for de-centering English by exposing students to many languages in “language of the day” (LotD) activities. These activities broadened student knowledge of the world’s languages and improved student achievement on core analytical skills. This paper covers our implementation of LotD across two undergraduate phonetics and phonology courses, student and instructor reception, and suggestions for adaptation across subfields and course types.

Keywords: undergraduate teaching, linguistic diversity, active learning, skills-based grading

1. Introduction

Many introductory linguistics courses rely on English sounds, words, and sentences as examples to teach core concepts in linguistics. For example, many textbooks teach phonetics by introducing key phonetic terms and skills with English sounds only. When sounds of other languages are covered, they are often included after the English sounds and in less depth.This limits student learning and centers English in the linguistics educational experience. We developed a method for de-centering English by exposing students to many languages in“language of the day” (LotD) activities. These activities broadened student knowledge of the world’s ~7000 languages and improved student achievement on core analytical skills. We implemented LotD in two undergraduate phonetics and phonology courses, but the method can be adapted to other subfields and course types.

LotD exposes students to a new language every day, with two main goals. First, educating students about a variety of languages is a strategy for advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion. Thoughtfully incorporating many languages into the curriculum de-centers prestige varieties of English, showcases linguistic diversity, and provides opportunities to discuss linguistic injustice. LotD can be localized for different areas and paired with discussion of land acknowledgements or other local efforts to recognize and support indigenous language communities. These ideas follow existing work in linguistics prioritizing indigenous languages in research and teaching (De Korne 2021; Hale 1997; Leonard 2023, 2023b; Riera-Gil 2019). LotD also allows instructors to center students’ personal experiences by selecting languages that are important to students.

LotD is also a strategy for advancing evidence-based teaching and improving student achievement. Involving the students in hands-on activities with each new language provides opportunities for active and experiential learning. Students can apply their knowledge by practicing skills with new data and languages in each class. Such active learning strategies improve learning outcomes for students (e.g.,Willingham 2014; Lang 2021). LotD also pairs well with innovative grading systems that prioritize frequent participation, such as skills-based grading.

This paper covers our implementation of LotD across two undergraduate phonetics and phonology courses at the University of Texas Arlington, a large state institution with a diverse student body. It is a federally designated Hispanic Serving Institution and an Asian-American Native-American Pacific Islander Serving Institution. Our phonetics and phonology classes are typically between 20 and 40 students, most of which are majoring or minoring in linguistics, TESOL, or critical language studies.

2. Implementation

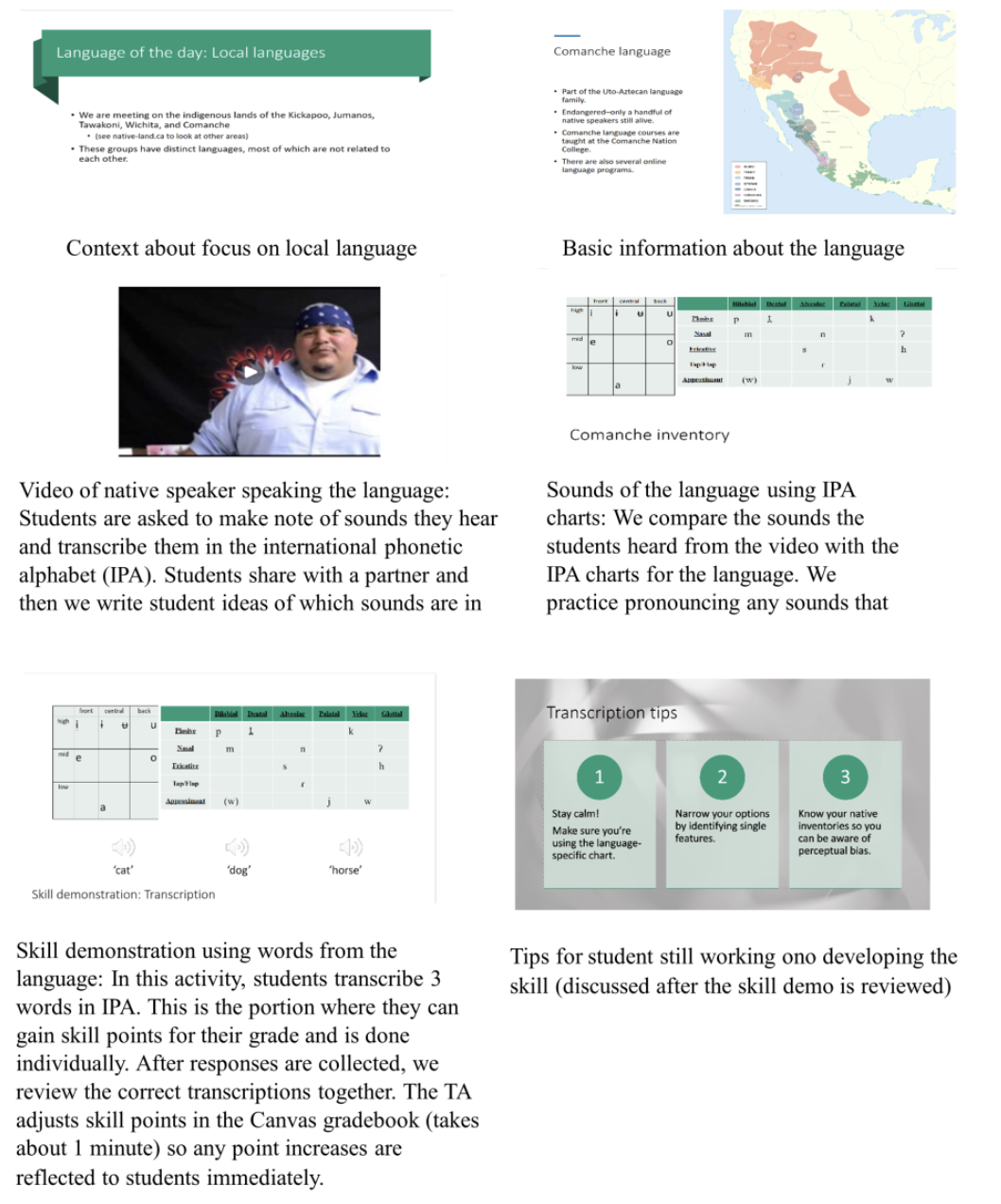

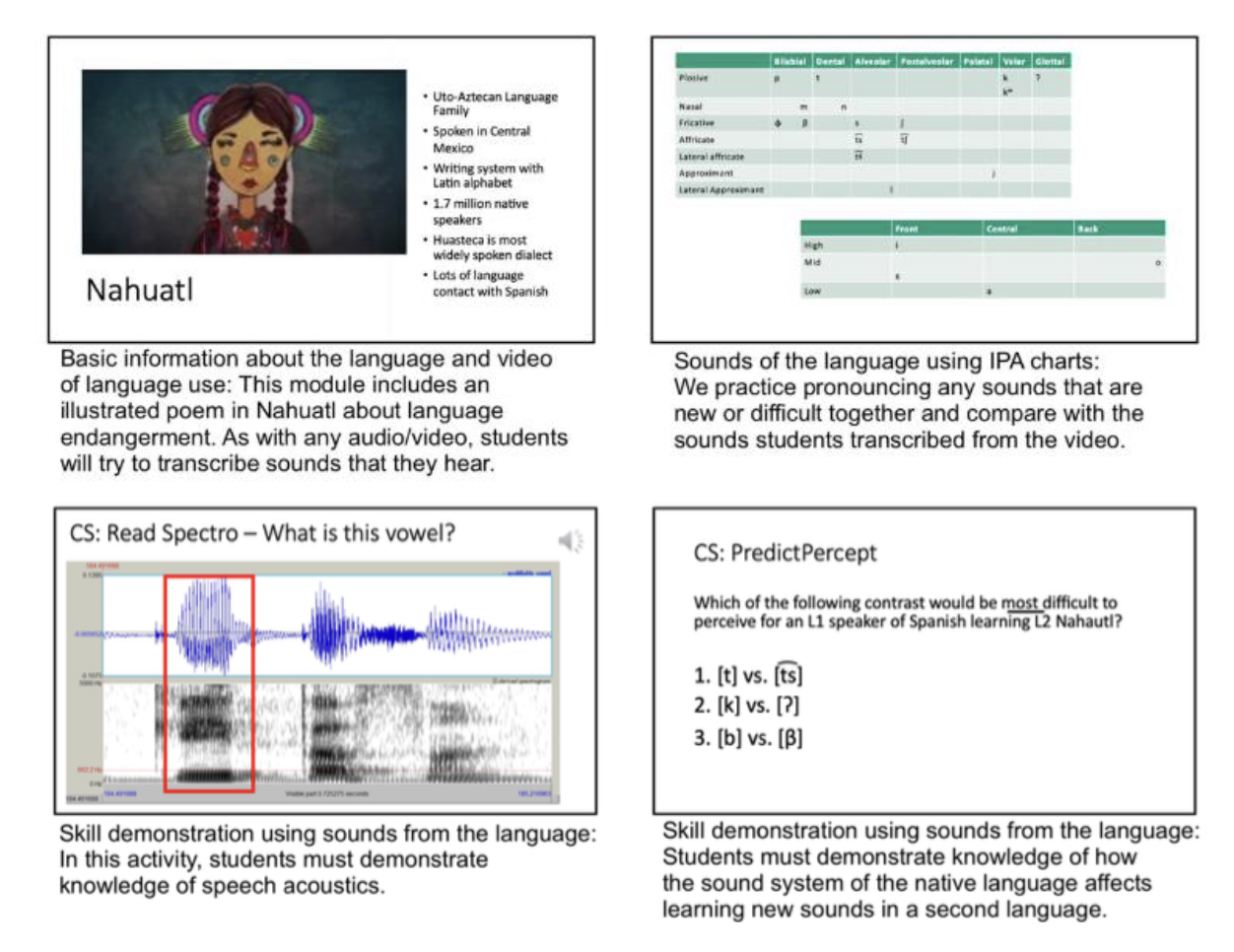

LotD introduces a language in a short module at the beginning of every class.The length could range from 5 to 20 minutes depending on the class time. Our implementations were in 80-minute classes, so most LotD modules were between 10 and 20minutes. Each module has three key components: basic information about the language ,audio/video of language use, and an application activity where students practice core analytical skills with data from the language. The basic information about the language typically included demographic information and phonological inventories (though this could be adapted to include other information for courses in other topics). We prioritized indigenous and minoritized languages as LotD, with focus on local languages and languages with which students have personal experience. The activities were paired with the course’s main content and increased in complexity as students developed skills throughout the semester. For example, at the beginning of the term students often described IPA symbols. At the end of the term, students progressed to predicting what sounds would be most difficult to perceive for L1 speakers of one LotD learning another LotD.

It is important to ensure all languages are presented respectfully. One strategy we use to address this is to present information on groups who use the language, including videos of native speakers using the language, to avoid presenting languages solely as analytical objects void of their social contexts. Instructors are encouraged to prioritize sources produced by the language community, cite sources, and note the relationship of authors to the language community. Although the modules are only 5-20 minutes in length, these strategies fore-ground respectful presentation of the language communities.

Figures 1 and 2 contain two example slide decks from LotD modules. While slides pro-vide visual structure and a vehicle for showing key images, the LotD modules are not lecture-based. The key component of the module is the hands-on application activity. Because the modules are heavily activity-based, preparing the slides was not overly time-intensive for instructors and TAs; preparing new modules typically took between 10 and 30 minutes. We utilized open-access resources for audio such as the Handbook of the IPA, the UCLA Phonetics Archive, and other publicly available sources.

We paired LotD with skills-based grading (SG; Buckmiller 2017; Zuraw et al. 2019), a non-traditional grading system where students build mastery of core skills throughout the semester and therefore are not penalized for struggling on the first attempt. The set of core skills is determined by instructors a priori, along with the number of times students need to correctly demonstrate the skill for mastery. For example, in our course the students needed to correctly transcribe in IPA 20 times to achieve mastery of the IPA transcription skill. Students often transcribed words from LotD to gain points towards their mastery of the transcript-on skill. The integration of SG and LotD provided an incentive to participate in the LotD activities while lowering student stress – if they get the question right, they add to their skill proficiency, but nothing happens to their grade if they get the question wrong. Making the LotD activities graded also provided incentives for students to not only come to class, but also to pay attention to the LotD content because each LotD module came with an opportunity to improve their grade. While the pairing of LotD and skills grading is synergistic, LotD can be implemented under any grading scheme, including more traditional grading. Activities done in class may be ungraded, graded for participation points, or as part of a larger traditionally graded assignment. Other versions of our course have included LotD as an ungraded warm-up activity at the beginning of class. Students from that course still found it to be valuable and commented that they looked forward to learning what the language would be each day.

3. Reception and impact

Including a greater variety of languages in class has been positive for students and instructors. Students had better performance on core skills (i.e.,phonetic transcription, underlying representations, etc.) relative to prior versions of the samec ourse without LotD. We saw the most improvement on skills with which students typically struggle. Key results are provided in Table 1. Before LotD, 60% of students achieved full mastery (~A level) on phonetic transcription and related skills. Since LotD, 80% of students have achieved full mastery of these skills. Similarly, while only 47% of students mastered the underlying representation skill before LotD, 65% of students mastered the skill afterLotD. More modest improvement was observed for other skills which tend to be easier for students. For example, 82% of students mastered the complementary distribution skill before LotD and this percentage only rose to 84% with LotD. While this is not a major improvement, this skill already had high percentage mastery before LotD, so it is possible that this achievement was already at ceiling. In addition to an improved level of mastery, students also mastered skills faster with LotD due to the increased number of opportunities to practice skills during class.

| Core skill | % of students achieving full mastery (A-level) | |

| Without LotD (2 semesters) | With LotD (2 semesters) | |

| IPA transcription | 60% | 80% |

| Underlying representations | 47% | 65% |

| Identifying distributions | 82% | 84% |

Student interest in world languages also increased, as evident in conversations with students and final projects, where students analyze any language of their choosing. The diversity of languages chosen by students for their final project increased with LotD, with more students choosing non-Indo-European and less commonly taught languages (Table 2). Even though 30% of students still choose to work on an Indo-European language after LotD, the Indo-European languages chosen have shifted. Before LotD, these languages were mostly colonial languages US students learn in school like Spanish, French, or German. After LotD, students chose more languages that were new to them and minoritized in the US context, such as Farsi and Hindi.

| Final project languages | Without LotD (2 semesters) | With LotD (2 semesters) |

| % Indo-European | 45% | 30% |

| % Top 10 in # speakers | 21% | 20% |

| # families represented | 7 | 9 |

Students had positive reception of LotD in mid-semester and end-of-semester surveys. In all open-ended surveys across the two courses where LotD was implemented, 40% of responding students volunteered LotD as “something that helped my learning” and 20% named LotD as “the best thing about the course”. Themes in student comments included greater interest in world languages and the utility of practicing skills during class. Example comments are provided in Table 3.

| Student responses about language of the day from open-ended surveys |

| “The language of the day is useful in the way it brings up skill demos of things we are currently working on so we can converse on topics in a problem set kind of way. That way it can be visualized more easily for me to learn.” |

| “The language of the day [is helping my learning] because we are exposed to a variety of languages that help us practice our perception and our transcription skill.” |

| “The visual aids used, the daily skill opportunities, and the language of the day all added a good amount of variation to classes to keep us engaged.” |

| “The languages of the day were also really interested (sic) to see how the concepts we were learning applied to different languages, and I really loved it!” |

The LotD activity allows teaching assistants (TAs) to build confidence teaching on a smaller scale compared to teaching a full class. Since the LotD activity is only in the first few minutes of class, it is a low-stakes way for TAs to gain classroom experience. It provides a hands-on opportunity for them to learn how to make instructional materials and promote student involvement in a lesson. As LotD covers many languages throughout the semester, TAs can learn alongside the students about these languages while gaining teaching experience. For all instructors, LotD presented self-reflection opportunities, as we were often learning more about the featured languages and communities ourselves when preparing materials. This created a collaborative learning experience across the lead instructor, TAs, and students.

4. Conclusion

This paper has proposed LotD as a method with several benefits to students and instructors. It aligns with evidence-based teaching practices like active learning; it advances justice, equity, diversity and inclusion; and it provides a collective learning environment for both students and instructors as well as improved student learning outcomes on technical skills. If instructors want to implement LotD in their courses, we recommend the following first steps: (1) identify the languages that are locally important in your area and to your student population; and (2) identify core skills that are important for students to practice in your course. All the languages covered in a LotD semester need not be local, but prioritizing local languages is a good starting point.

Instructors who have been using LotD may also consider some opportunities for expanding and enriching the practice. One improvement on the basic LotD model is ensuring the LotD content is well-integrated with the rest of the course. This means that the main content of each day corresponds well to the LotD content, including additional activities using data from that language throughout the class. This requires additional instructor time to re-arrange and revise materials for each class. Re-designing one or two classes each term is a more manageable approach that provides continual improvement on each implementation. Another way of enriching LotD could be including students as presenters. Students could present their own LotD modules with languages they are interested in through either a graded requirement or an opportunity for extra credit.

Instructors in other subfields might utilize LotD with slightly different methods better suited to their topic. Our implementation of LotD was used in undergraduate phonetics and phonology, but the method can be adapted to other types of linguistics and language classes. Syntax classes might change the basic linguistic information about the language to include things like default word order instead of phonological inventories. Sociolinguistics classes might implement LotD by choosing varieties associated with particular social groups. Classes that focus on linguistics of a particular language (or language and literature classes) might do a “dialect of the day” adaptation using the same structure as LotD.

References

Buckmiller, Tom, Randal Peters & Jerrid Kruse. 2017. Questioning points and percentages: Standards-based grading in higher education. College Teaching 65. 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2017.1302919.

De Korne, Haley. 2021. Language activism: Imaginaries and strategies of minority language equality. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Hale, Ken. 1997. Some observations on the contributions of local languages to linguistic science. Lingua 100(1). 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(96)00029-0.

Lang, James M. 2021. Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Leonard, Wesley Y. 2023. Challenging “extinction” through modern Miami language practices. In Lydia Liu & Anupama Rao (eds.), Global language justice, 126–165. Chichester, NY: Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/liu-21038-007.

Leonard, Wesley Y. 2023b. Refusing “endangered languages” narratives. Daedalus 152 (3): 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02018.

Riera-Gil, Elvira. 2019. The communicative value of local languages: An underestimated interest in theories of linguistic justice. Ethnicities 19(1). 174–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796818786310.

Willingham, Daniel T. 2014. Strategies that make learning last. Educational Leadership 72(2). 10–15.

Zuraw, Kie, Ann M. Aly, Isabelle Lin & Adam J. Royer. 2019. Gotta catch’em all: Skills grading in undergraduate linguistics. Language 95(4). e406–e427. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2019.0081.