91 Brønsted-Lowry Acids and Bases

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and recognize Arrhenius, Brønsted-Lowry, and Lewis acids and bases.

- Identify acids, bases, and conjugate acid-base pairs according to the Brønsted-Lowry definition

- Write equations for acid and base ionization reactions

- Use the ion-product constant for water to calculate hydronium and hydroxide ion concentrations

- Describe the acid-base behavior of amphiprotic substances

Definitions of Acids and Bases

The acid-base reaction class has been studied for quite some time. In 1680, Robert Boyle reported traits of acid solutions that included their ability to dissolve many substances, to change the colors of certain natural dyes, and to lose these traits after coming in contact with alkali (base) solutions. In the eighteenth century, it was recognized that acids have a sour taste, react with limestone to liberate a gaseous substance (now known to be CO2), and interact with alkalis to form neutral substances. In 1815, Humphry Davy contributed greatly to the development of the modern acid-base concept by demonstrating that hydrogen is the essential constituent of acids. Around that same time, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac concluded that acids are substances that can neutralize bases and that these two classes of substances can be defined only in terms of each other.

It was not until the nineteenth century that acids and bases were more strictly defined in terms of the specific chemical reaction involved. Today there are three commonly used definitions of acids and bases: the Arrhenius, Brønsted-Lowry and Lewis definitions. We will have a brief look at the Arrhenius and Lewis definitions, but this chapter will focus on Brønsted-Lowry acids and bases.

Arrhenius acids and bases

The significance of hydrogen was reemphasized in 1884 when Svante Arrhenius defined an acid as a compound that dissolves in water to yield hydrogen cations (now more commonly called hydronium ions) and a base as a compound that dissolves in water to yield hydroxide anions. For example, if hydrochloric acid (HCl) gas is bubbled through water, it will dissociate to form hydronium ions (H3O+), and so HCl is an Arrhenius acid

HCl(g) + H2O(l) → H3O+(aq) + Cl–(aq)

If sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is dissolved in water, it will form hydroxide ions, and so NaOH is an Arrhenius base

NaOH(s) → Na+(aq) + OH–(aq)

Brønsted-Lowry acids and bases

More than a century ago, Johannes Brønsted and Thomas Lowry proposed a more general description in which acids and bases were defined in terms of the transfer of hydrogen ions (protons, H+). According to the Brønsted-Lowry definition, an acid is a compound that donates a proton to another compound; a base is a compound that accepts a proton. Accordingly, an acid-base reaction can be defined as the transfer of a proton from a proton donor (acid) to a proton acceptor (base).

Thus, the Arrhenius acid HCl is also a Brønsted-Lowry acid: when in aqueous solution, HCl will donate its proton to water – which is a Brønsted-Lowry base – to form the hydronium ion. This is the same reaction as shown above, only the way of looking at the reaction is different:

HCl(g) + H2O(l) → H3O+(aq) + Cl–(aq)

All Arrhenius acids are, thus, Brønsted-Lowry acids. The Brønsted-Lowry definition of an acid is broader than the Arrhenius definition, since the Arrhenius definition is limited to acids that form hydronium ions in aqueous solution, whereas the Brønsted-Lowry definition allows different solvents and even different phases (e.g. the gas phase).

Similarly, the Arrhenius base NaOH is also a Brønsted-Lowry base: when in aqueous solution. As you can see in the reaction below, the hydroxide accepts a proton from hydrochloric acid to form water:

HCl(g) + NaOH(aq) → NaCl(aq) + HOH(l)

This is a neutralization reaction, which will be discussed later in this chapter. Many Brønsted-Lowry acids and bases are also Arrhenius acids and bases, but there are some exceptions. For example, ammonia (NH3) is not an Arrhenius base (since it cannot directly release hydroxide ions in water), but it is a Brønsted-Lowry base since it can accept a proton to form the ammonium ion (NH4+). This proton could be donated by water (in aqueous solution), but in this case the reaction will not go to completion (since ammonia is a weak base, discussed later in this chapter):

HOH(l) + NH3(aq) ![]() OH–(aq) + HNH3+(aq)

OH–(aq) + HNH3+(aq)

The ammonia could also accept a proton from a Brønsted-Lowry acid such as HCl, as shown below. In this case, the reaction does go to completion, since HCl is a strong acid (discussed later in this chapter).

HCl(g) + NH3(aq) → Cl–(aq) + HNH3+(aq)

Lewis acids and bases

The Lewis definition of acids and bases is even more general than the Brønsted-Lowry definition. A Lewis acid is one that can accept an electron pair; a Lewis base is one that can donate an electron pair. All Arrhenius and Brønsted-Lowry acids are also Lewis acids; all Arrhenius and Brønsted-Lowry bases are also Lewis bases. However, the focus when looking at Lewis acids and bases is on the electron pairs, not the proton. For example, as discussed above, ammonia is a Brønsted-Lowry base since it can accept a proton. However, ammonia is also a Lewis base since it can donate an electron pair, as shown below:

Brønsted-Lowry acid-base reactions

Conjugate acid-base pairs

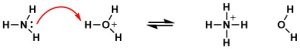

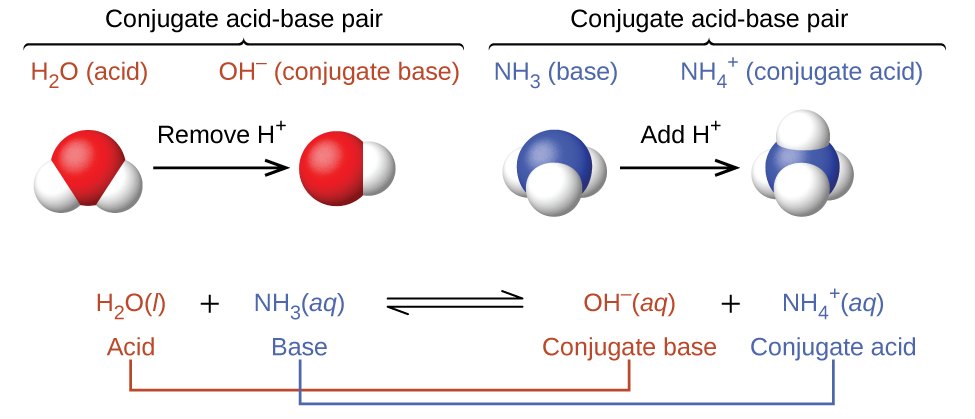

The concept of conjugate pairs is useful in describing Brønsted-Lowry acid-base reactions. When an acid donates H+, the species that remains is called the conjugate base of the acid, since it reacts as a proton acceptor in the reverse reaction. Likewise, when a base accepts H+, it is converted to its conjugate acid. The reaction between water and ammonia illustrates this idea. In the forward direction, water acts as an acid by donating a proton to ammonia and subsequently becoming a hydroxide ion, OH−, the conjugate base of water. The ammonia acts as a base in accepting this proton, becoming an ammonium ion, NH4+, the conjugate acid of ammonia. In the reverse direction, a hydroxide ion acts as a base in accepting a proton from ammonium ion, which acts as an acid.

Note that conjugate acid-base pairs differ by the transfer of one proton. Thus, while water (H2O) and hydroxide (OH–) are a conjugate acid-base pair, the hydronium ion (H3O+) and hydroxide (OH–) are not a conjugate acid-base pair since they differ by the transfer of two protons.

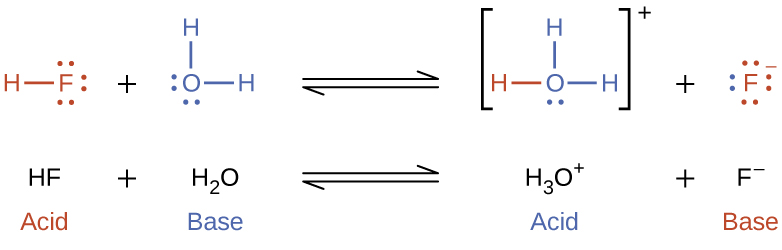

The reaction between a Brønsted-Lowry acid and water is called acid ionization. For example, when hydrogen fluoride dissolves in water and ionizes, protons are transferred from hydrogen fluoride molecules to water molecules, yielding hydronium ions and fluoride ions:

Base ionization of a species occurs when it accepts protons from water molecules. In the example below, pyridine molecules, C5NH5, undergo base ionization when dissolved in water, yielding hydroxide and pyridinium ions:

![This figure has two rows. In both rows, a chemical reaction is shown. In the first, structural formulas are provided. In this model, in red, is an O atom which has H atoms singly bonded above and to the right. The O atom has lone pairs of electron dots on its left and lower sides. This is followed by a plus sign. The plus sign is followed, in blue, by an N atom with one lone pair of electron dots. The N atom forms a double bond with a C atom, which forms a single bond with a C atom. The second C atom forms a double bond with another C atom, which forms a single bond with another C atom. The fourth C atom forms a double bond with a fifth C atom, which forms a single bond with the N atom. This creates a ring structure. Each C atom is also bonded to an H atom. An equilibrium arrow follows this structure. To the right, in brackets is a structure where an N atom bonded to an H atom, which is red, appears. The N atom forms a double bond with a C atom, which forms a single bond with a C atom. The second C atom forms a double bond with another C atom, which forms a single bond with another C atom. The fourth C atom forms a double bond with a fifth C atom, which forms a single bond with the N atom. This creates a ring structure. Each C atom is also bonded to an H atom. Outside the brackets, to the right, is a superscript positive sign. This structure is followed by a plus sign. Another structure that appears in brackets also appears. An O atom with three lone pairs of electron dots is bonded to an H atom. There is a superscript negative sign outside the brackets. To the right, is the equation: k equals [ C subscript 5 N H subscript 6 superscript positive sign ] [ O H superscript negative sign] all divided by [ C subscript 5 N H subscript 5 ]. Under the initial equation, is this equation: H subscript 2 plus C subscript 5 N H subscript 5 equilibrium arrow C subscript 5 N H subscript 6 superscript positive sign plus O H superscript negative sign. H subscript 2 O is labeled, “acid,” in red. C subscript 5 N H subscript 5 is labeled, “base,” in blue. C subscript 5 N H subscript 6 superscript positive sign is labeled, “acid” in blue. O H superscript negative sign is labeled, “base,” in red.](https://pressbooks.openedmb.ca/app/uploads/sites/94/2024/05/CNX_Chem_14_01_NH3_img-1.jpg)

Amphiprotic and amphoteric species

The preceding ionization reactions suggest that water may function as both a base (as in its reaction with hydrogen fluoride) and an acid (as in its reaction with ammonia). Species capable of either donating or accepting protons are called amphiprotric. A closely related term is amphoteric, which refers to a species capable of acting of either an acid or a base. (Recall that some acids and bases do not donate/accept protons, so while all amphiprotic species are amphoteric, not all amphoteric species are amphiprotic). The equations below show the two possible acid-base reactions for two amphiprotic species, bicarbonate ion and water:

The first equation represents the reaction of bicarbonate as an acid with water as a base, whereas the second represents reaction of bicarbonate as a base with water as an acid. When bicarbonate is added to water, both these equilibria are established simultaneously and the composition of the resulting solution may be determined through appropriate equilibrium calculations, as described later in this chapter.

Representing the Acid-Base Behavior of an Amphoteric Substance

Write separate equations representing the reactions of HSO3– (in aqueous solution)

(a) as an acid with OH−

(b) as a base with HI

Solution

(a) HSO3–(aq) + OH–(aq) ![]() SO32-(aq) + H2O(l)

SO32-(aq) + H2O(l)

(b) HSO3–(aq) + HI(aq) ![]() H2SO3(aq) + I–(aq)

H2SO3(aq) + I–(aq)

Check Your Learning

Write separate equations representing the reactions of H2PO4– (in aqueous solution).

(a) as a base with HBr

(b) as an acid with OH−

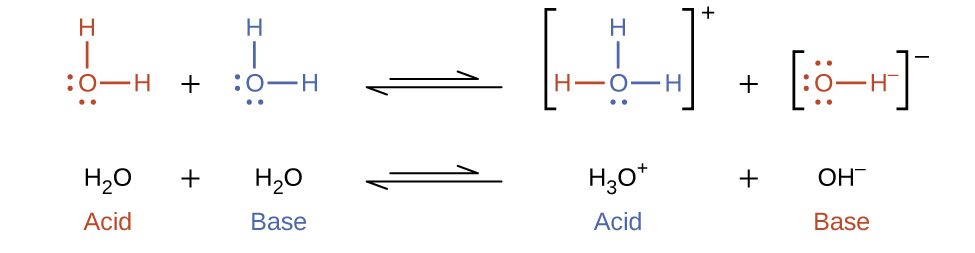

Autoionization

Interestingly, molecules of an amphiprotic substance can react with one another as illustrated for water in the equations below:

The process in which like molecules react to yield ions is called autoionization. Liquid water undergoes autoionization to a very slight extent; at 25 °C, approximately two out of every billion water molecules are ionized. The extent of the water autoionization process is reflected in the value of its equilibrium constant (also called the ion-product constant). Since we use the equilibrium constant for the autoionization of water so frequently, it is given its own abbreviation as Kw:

The slight ionization of pure water is reflected in the small value of the equilibrium constant; at 25 °C, Kw has a value of 1.0 x 10−14. The process is endothermic, and so the extent of ionization and the resulting concentrations of hydronium ion and hydroxide ion increase with temperature. For example, at 100 °C, the value for Kw is about 5.6 x 10−13, roughly 50 times larger than the value at 25 °C.

Ion Concentrations in Pure Water

What are the hydronium ion concentration and the hydroxide ion concentration in pure water at 25 °C?

Solution

The autoionization of water yields the same number of hydronium and hydroxide ions. Therefore, in pure water, [H3O+] = [OH−] = x. At 25 °C:

So:

The hydronium ion concentration and the hydroxide ion concentration are the same, 1.0 x 10−7M.

Check Your Learning

The ion product of water at 80 °C is 2.4 x 10−13. What are the concentrations of hydronium and hydroxide ions in pure water at 80 °C?

The Inverse Relation between [H3O+] and [OH−]

A solution of an acid in water has a hydronium ion concentration of 2.0 x 10−6M. What is the concentration of hydroxide ion at 25 °C?

Solution

Use the value of the ion-product constant for water at 25 °C

to calculate the missing equilibrium concentration.

Rearrangement of the Kw expression shows that [OH−] is inversely proportional to [H3O+]:

Compared with pure water, a solution of acid exhibits a higher concentration of hydronium ions (due to ionization of the acid) and a proportionally lower concentration of hydroxide ions. This may be explained via Le Châtelier’s principle as a left shift in the water autoionization equilibrium resulting from the stress of increased hydronium ion concentration.

Substituting the ion concentrations into the Kw expression confirms this calculation, resulting in the expected value:

Check Your Learning

What is the hydronium ion concentration in an aqueous solution with a hydroxide ion concentration of 0.001 M at 25 °C?

Key Concepts and Summary

According to the Arrhenius definition of acids and bases, an acid is a compound that dissolves in water to yield hydronium ions (often called an Arrhenius acid); a base is a compound that dissolves in water to yield hydroxide anions (often called an Arrhenius base).

According to the Brønsted-Lowry definition of acids and bases, a compound that can donate a proton (a hydrogen ion) to another compound is an acid (often called a Brønsted-Lowry acid); the compound that accepts the proton is a base (often called a Brønsted-Lowry base). The species remaining after a Brønsted-Lowry acid has lost a proton is the conjugate base of the acid. The species formed when a Brønsted-Lowry base gains a proton is the conjugate acid of the base. Thus, an acid-base reaction occurs when a proton is transferred from an acid to a base, with formation of the conjugate base of the reactant acid and formation of the conjugate acid of the reactant base.

Amphiprotic species can act as both proton donors and proton acceptors. Water is the most important amphiprotic species. It can form both the hydronium ion, H3O+, and the hydroxide ion, OH− when it undergoes autoionization:

The ion product of water, Kw is the equilibrium constant for the autoionization reaction:

Key Equations

- Kw = [H3O+][OH−] = 1.0 x 10−14 (at 25 °C)

Section 91 Practice Problems

1. Write an equation that shows NH3 reacting as a base in aqueous solution. What is the conjugate acid of NH3?

2. Write equations that show H2PO4– acting both as an acid and as a base in aqueous solution. For each equation, indicate the conjugate acid/base pairs.

3. Show by suitable net ionic equations that each of the following species can act as a Brønsted-Lowry acid in aqueous solution:

(a) H3O+

(b) HCl

(c) CH3CO2H

(d) NH4+

(e) HSO4–

4. Show by suitable net ionic equations that each of the following species can act as a Brønsted-Lowry acid in aqueous solution:

(a) HNO3

(b) PH4+

(c) H2S

(d) CH3CH2COOH

(e) H2PO4–

5. Show by suitable net ionic equations that each of the following species can act as a Brønsted-Lowry base:

(a) H2O

(b) OH−

(c) NH3

(d) CN−

(e) S2−

(f) ![]()

6. Show by suitable net ionic equations that each of the following species can act as a Brønsted-Lowry base:

(a) HS−

(b) ![]()

(c) ![]()

(d) C2H5OH

(e) O2−

(f) H2PO4–

7. What is the conjugate acid of each of the following? What is the conjugate base of each?

(a) OH−

(b) H2O

(c) HCO3–

(d) NH3

(e) HSO4–

(f) H2O2

(g) HS−

(h) H5N2+

8. What is the conjugate acid of each of the following? What is the conjugate base of each?

(a) H2S

(b) ![]()

(c) PH3

(d) HS−

(e) ![]()

(f) ![]()

(g) H4N2

(h) CH3OH

9. Identify and label the Brønsted-Lowry acid, its conjugate base, the Brønsted-Lowry base, and its conjugate acid in each of the following equations:

(a) ![]()

(b) ![]()

(c) ![]()

(d) ![]()

(e) ![]()

(f) ![]()

(g) ![]()

Answer(s): The labels are Brønsted-Lowry acid = BA; its conjugate base = CB; Brønsted-Lowry base = BB; its conjugate acid = CA. (a) HNO3(BA), H2O(BB), H3O+(CA), ![]() (b) CN−(BB), H2O(BA), HCN(CA), OH−(CB); (c) H2SO4(BA), Cl−(BB), HCl(CA),

(b) CN−(BB), H2O(BA), HCN(CA), OH−(CB); (c) H2SO4(BA), Cl−(BB), HCl(CA), ![]() (d)

(d) ![]() OH−(BB),

OH−(BB), ![]() (CB), H2O(CA); (e) O2−(BB), H2O(BA) OH−(CB and CA); (f) [Cu(H2O)3(OH)]+(BB), [Al(H2O)6]3+(BA), [Cu(H2O)4]2+(CA), [Al(H2O)5(OH)]2+(CB); (g) H2S(BA),

(CB), H2O(CA); (e) O2−(BB), H2O(BA) OH−(CB and CA); (f) [Cu(H2O)3(OH)]+(BB), [Al(H2O)6]3+(BA), [Cu(H2O)4]2+(CA), [Al(H2O)5(OH)]2+(CB); (g) H2S(BA), ![]() HS–(CB), NH3(CA)

HS–(CB), NH3(CA)

10. Identify and label the Brønsted-Lowry acid, its conjugate base, the Brønsted-Lowry base, and its conjugate acid in each of the following equations:

(a) ![]()

(b) ![]()

(c) ![]()

(d) ![]()

(e) ![]()

(f) ![]()

(g) ![]()

11. What are amphiprotic species? Illustrate with suitable equations.

Answer(s): Amphiprotic species may either gain or lose a proton in a chemical reaction, thus acting as a base or an acid. An example is H2O. As an acid: ![]()

As a base: ![]()

12. State which of the following species are amphiprotic and write chemical equations illustrating the amphiprotic character of these species:

(a) H2O

(b) ![]()

(c) S2−

(d) ![]()

(e) ![]()

13. State which of the following species are amphiprotic and write chemical equations illustrating the amphiprotic character of these species.

(a) NH3

(b) ![]()

(c) Br−

(d) ![]()

(e) ![]()

Answer(s):

amphiprotic:

(a) NH3 + H3O+ ![]() NH4+ + H2O

NH4+ + H2O

![]()

(b) ![]()

![]()

not amphiprotic: (c) Br−; (d) ![]() (e)

(e) ![]()

14. Which of the following does not fit the definition of a Brønsted Acid?

(a) H3PO4

(b) H2PO4–

(c) H2O

(d) NH4+

(e) CO2

15. Which of the following does not fit the definition of a Brønsted Base?

(a) NH3

(b) H2O

(c) NH4+

(d) HCO3–

(e) CO32–

16. Is the self-ionization of water endothermic or exothermic? The ionization constant for water (Kw) is 2.9 x 10−14 at 40 °C and 9.3 x 10−14 at 60 °C.

Glossary

- acid ionization

- reaction involving the transfer of a proton from an acid to water, yielding hydronium ions and the conjugate base of the acid

- amphiprotic

- species that may either donate or accept a proton in a Bronsted-Lowry acid-base reaction

- amphoteric

- species that can act as either an acid or a base

- autoionization

- reaction between identical species yielding ionic products; for water, this reaction involves transfer of protons to yield hydronium and hydroxide ions

- base ionization

- reaction involving the transfer of a proton from water to a base, yielding hydroxide ions and the conjugate acid of the base

- Brønsted-Lowry acid

- proton donor

- Brønsted-Lowry base

- proton acceptor

- conjugate acid

- substance formed when a base gains a proton

- conjugate base

- substance formed when an acid loses a proton

- ion-product constant for water (Kw)

- equilibrium constant for the autoionization of water. Like any other equilibrium constant, KW is only a constant at a constant temperature.