Chapter 14: Winged Wonders: The Beauty of Birds

Courtesy: By Caspar David Friedrich – Zeno.org, ID number 20004019431, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20118664

“Birds have ever been symbols of our highest aspirations. As divine messengers, symbols of our yearning for the heavens, or avatars of glorious song and colour, they have stirred our imaginations from the moment we first looked into the sky. Whether as the Christian dove, or Quetzalcoatl–the Aztec Plumed serpent–or in Plato’s vision of the human soul growing wings and feathers, religion and philosophy have looked to birds as representatives of our better selves–that part of us not bound to the earth.” (inside cover, The bedside book of birds by Graeme Gibson, Anchor Canada, 2005).

“Birds connect people with nature. They add beauty, sound and colour to our world. They provide countless opportunities for enjoyment to birders and outdoor enthusiasts and have cultural and spiritual importance for many people. They contribute many environmental benefits, including pollination, insect and rodent control, and seed dispersal. Birds are also good indicators of environmental health because they are highly visible and relatively easy to study. Observing birds can give us a picture of what is going on in the world.” (Government of Canada).

The Beauty of Birds: Questions for Discussion and Reflection

- There are over 10,000 species of birds with over 1,480 species considered globally threatened. What thoughts about birds come to your mind as you view the following art images and related poems?

- Which species of birds have become extinct due to habitat destruction, and “killing for sport,” and captivity for commercial purposes? What efforts are being made to protect birds? (To read more about protecting avian biodiversity please open the link here).

- Birds are often associated with symbols of freedom and peace yet so many have been captured to spend their lives in a cage. Humans values freedom yet are too often intent on “capturing” animals. Why?

- How can attitudes, beliefs, and values be transformed so that all lives (human and non-human) are valued?

- Birds are vital players in many myths, legends, and folktales across cultures. Explore a myth, legend, or folklore that has a bird as the central player. ( e.g. The raven is the centre of many Indigenous creation stories and Finland’s national epic poem “The Kalevala” features a bird and her eggs which beome the earth and sky.

- Explore the ancient origins of birds and write a poem, essay, or other creative work that highlights the special features of the bird.

- Explore the symbolism of birds and create a chart with a photo, art image, or your own illustration of the bird, its characteristics, symbolism, and habitat.

Resources

Biodiversity Heritage Library link here.

To learn more about the world of birds, please open the National Geographic links here and here.

National Geographic: The World of Birds Essay: How Many Birds are There in the World?

Incredible Photo Gallery of Birds-Worldwide here.

National Geographic Photo Arc.

Ornithology Illustrations Internet Library.

Discovery Poetry: Poems about Birds Poems

He. Where thou dwellest, in what grove,

Tell me Fair One, tell me Love;

Where thou thy charming nest dost build,

O thou pride of every field!

She. Yonder stands a lonely tree,

There I live and mourn for thee;

Morning drinks my silent tear,

And evening winds my sorrow bear.

He. O thou summer’s harmony,

I have liv’d and mourn’d for thee;

Each day I mourn along the wood,

And night hath heard my sorrows loud.

She. Dost thou truly long for me?

And am I thus sweet to thee?

Sorrow now is at an end,

O my Lover and my Friend!

He. Come, on wings of joy we’ll fly

To where my bower hangs on high;

Come, and make thy calm retreat

Among green leaves and blossoms sweet

Takeaways, Insights, and Further Inquiry

- “Birds have been around for more than 150 million years by the time humans appeared on the scene. We came to self-awareness surrounded by them, and as there were few of us, birds would not yet have learned to fear us: as Charles Darwin and others discovered, they could have been knocked off their nests with a stick. Doubtless birds and their eggs were our first fast food. And birds would have been present in great numbers. As recently as 1813, John James Audubon rode all day under a sky filled with migrating pigeons. He reckoned that a billion birds had flown past him by nightfall. In 1866, another legendary flight arrived in southern Ontario; over a mile wide, with an estimated two birds per square yard, it took fourteen hours to pass overhead. Subsequent estimates suggest there were more than three billion birds in that assembly.”-Graeme Gibson, 2005. The bedside book of birds, pp. 39-40).

- “Archaeopteryx (“Ancient wing”) is a famous fossil of what is thought to be the oldest known bird. While the Archaeopteryx was thought to be a “missing link” between reptiles and birds, modern research has now classified it as a relative of birds. “The Archaeopteryx lived in the Late Jurassic around 150 million years ago, in what is now southern Germany, during a time when Europe was an archipelago of islands in a shallow warm tropical sea, much closer to the equator than it is now. Similar in size to a Eurasian magpie, with the largest individuals possibly attaining the size of a raven, the largest species of Archaeopteryx could grow to about 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) in length.” (Wikipedia).

- Throughout the millennia, birds have been associated with peace, freedom, beauty, spiritual enlightenment and aspects of the supernatural. In some cultures, birds are viewed as divine messengers that act as intermediaries between heaven and earth. To read more about birds in mythology please open the links here and here.

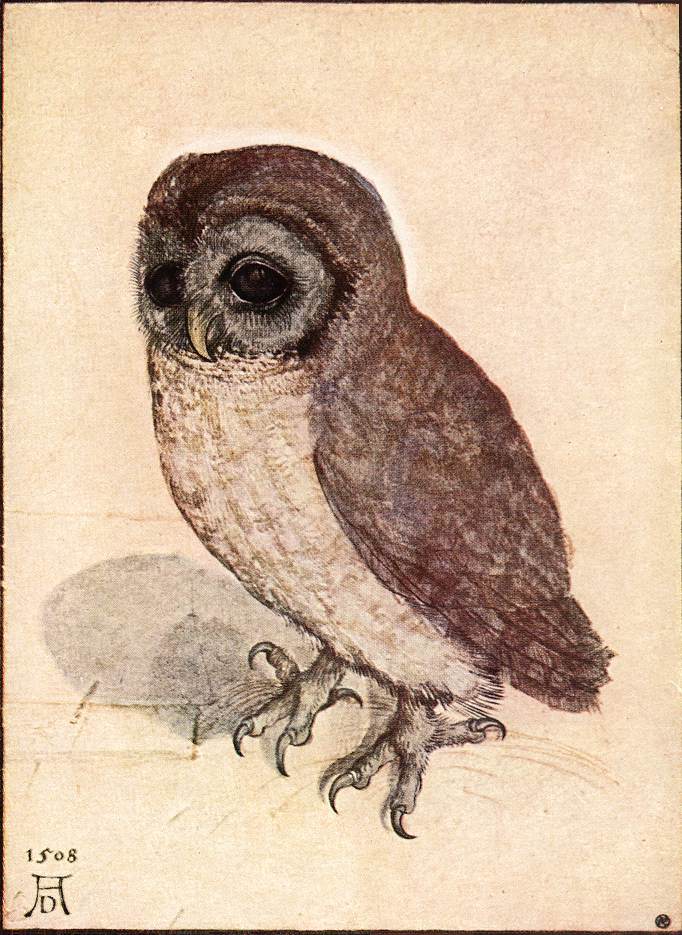

Courtesy: By Albrecht Dürer – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15393520

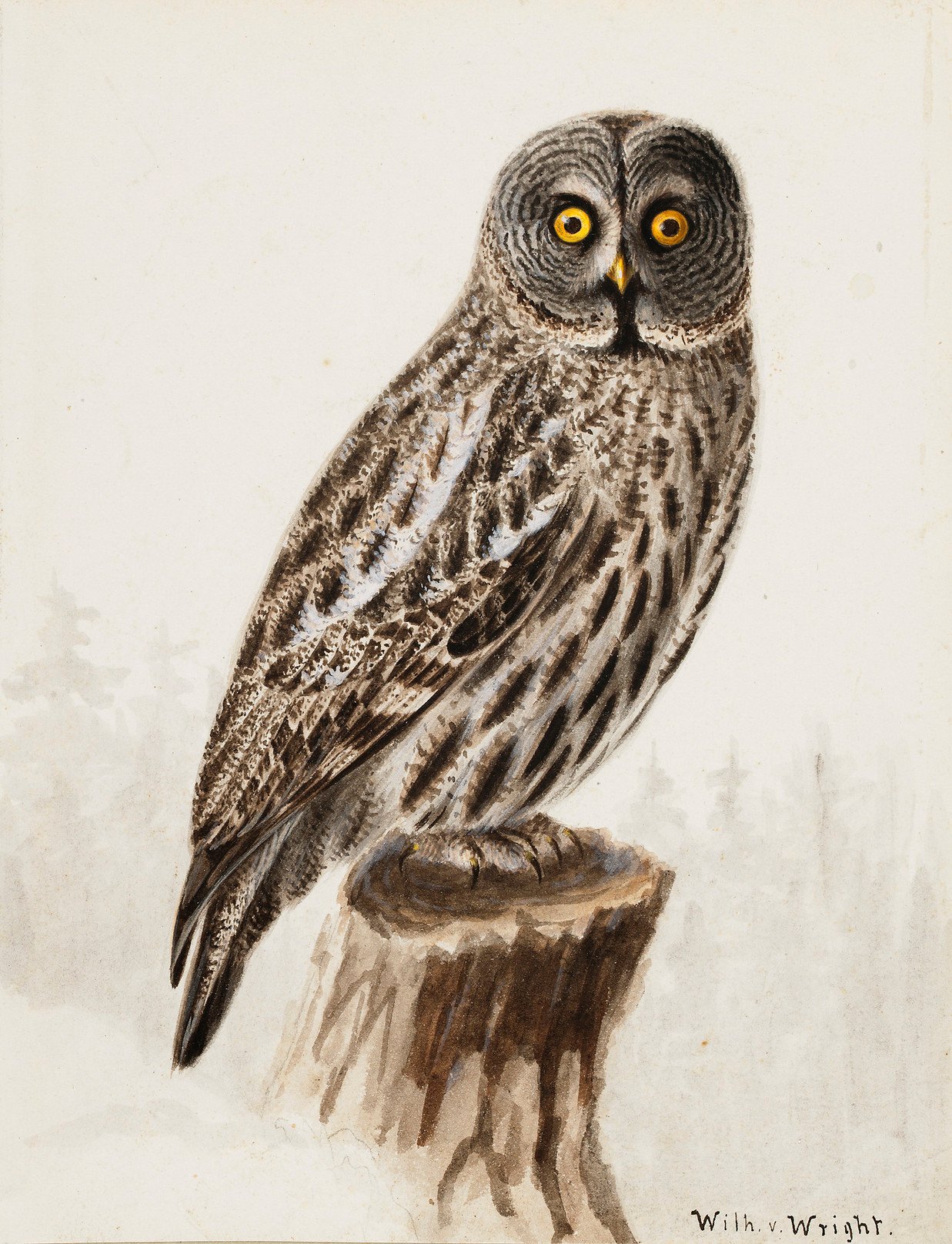

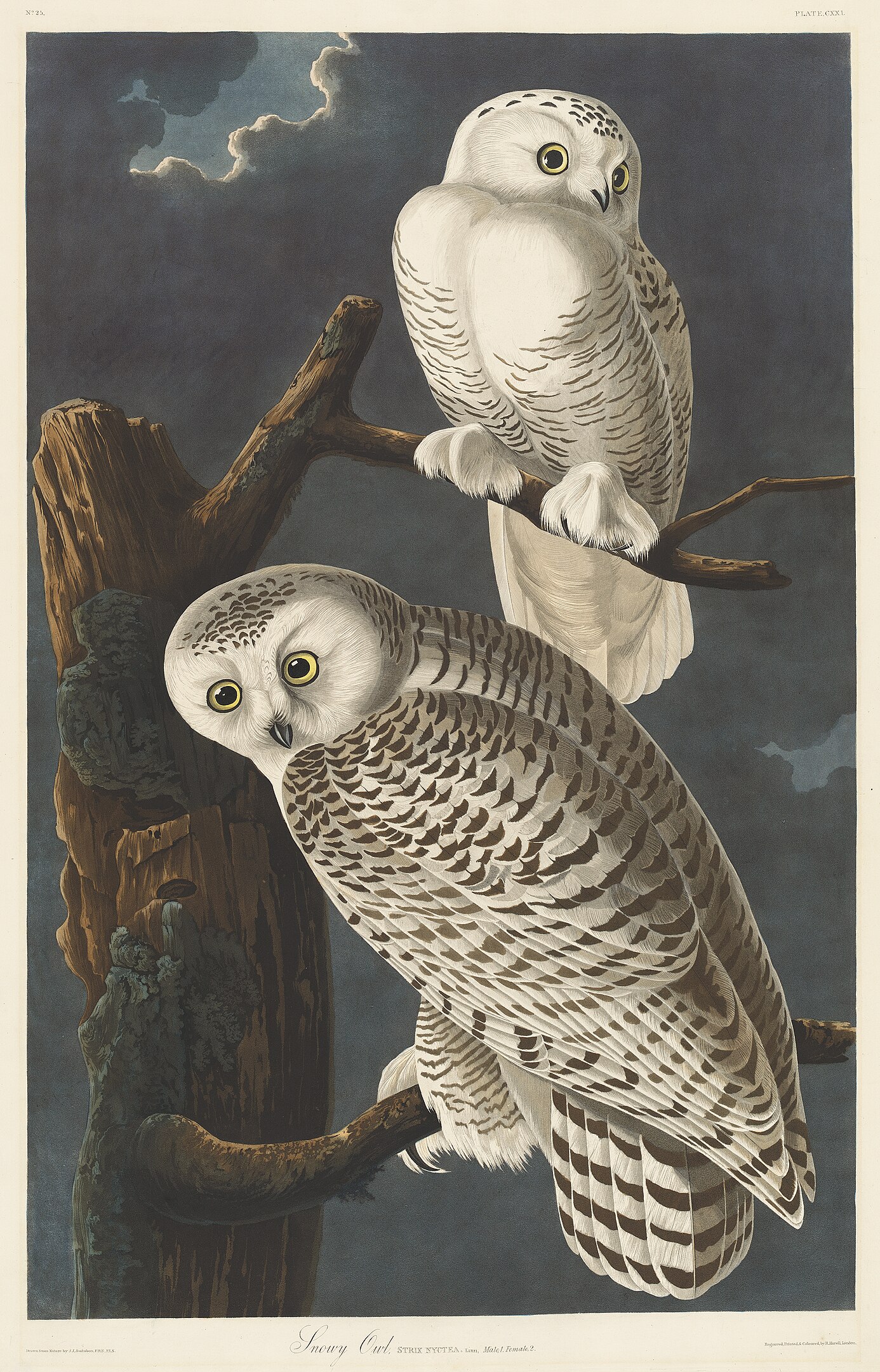

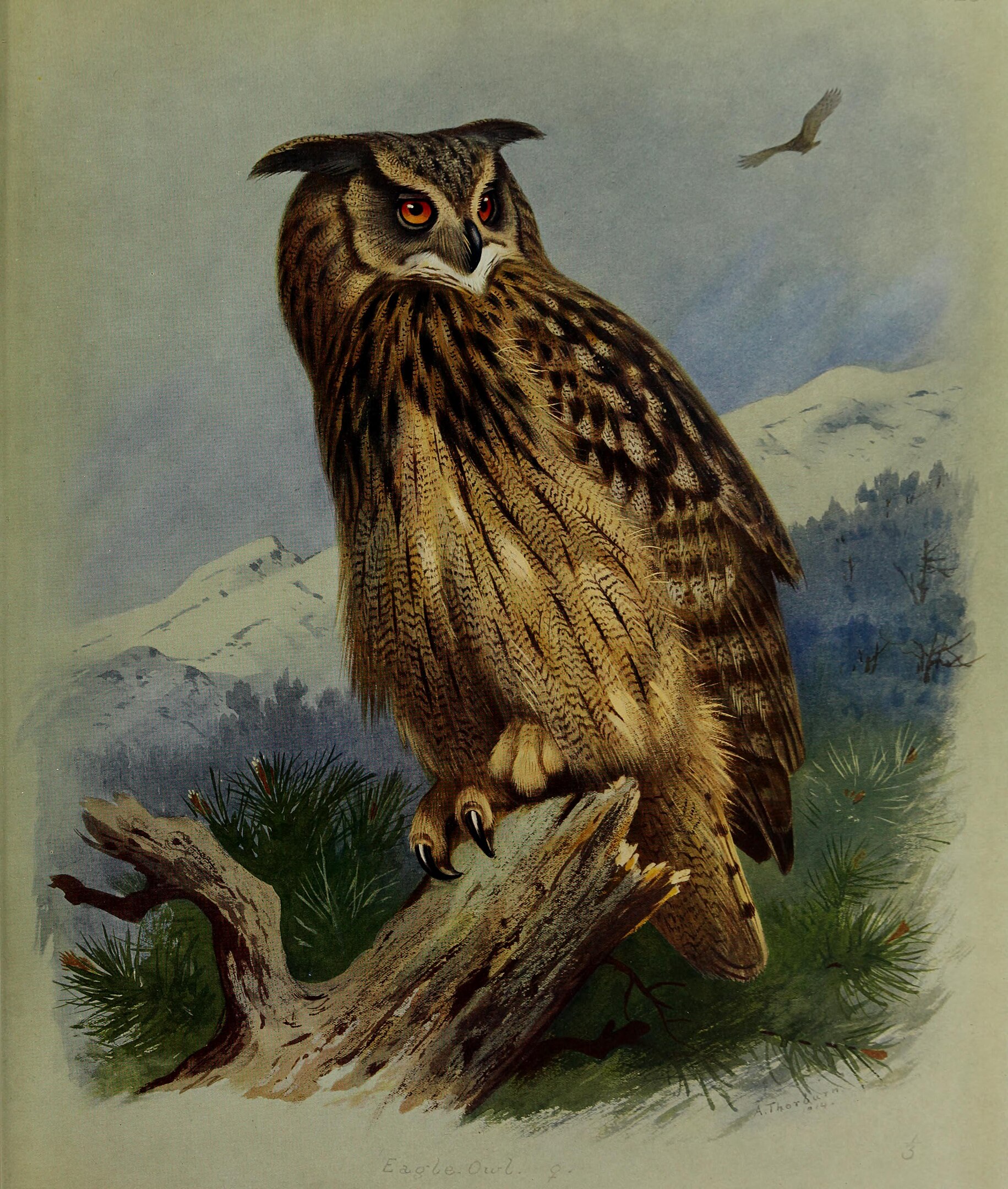

Owls

“There are about 200 species of owl found across the globe, except in icy wastes (although the Snowy Owl feeds on lemmings far north of the Arctic Circle). They hunt using their forward-facing eyes and keen hearing. Owls’ disc-shaped faces concentrate and focus the sounds into the ears, which are located asymmetrically. The asymmetry is though to aid the precision of detection of the sources of sounds and thus contributes to successful hunting. The basic owl form is of a fairly standard shape, but the sizes vary from the fish-catching Blakiston’s Fish-Owl (4.5 kg or 10 lb) of Russia to the Elf Owl (31 g. or 1 oz).

For the Kikuyu of Kenya, the Aztecs and Maya of Central America and the Cherokee in North America, owls were thought to be harbingers of death. in Malaya and Arabia owls were though to kill and carry off newborn babies. In such circumstances owls were often themselves victim, being killed sometimes chased at night with brands of fire, and if caught, set alight to put an end to any perceived bad luck.

Sometimes a culture’s attitude toward the owl can be more ambiguous. In China owls are found in Neolithic art of the sixth millennium BC onwards and feature especially in bronze objects from the Shang dynasty from the early second millennium BC. It has been suggested that the owl had an important role in Shang beliefs, and was perhaps a totemic animal and thought to be a messenger between the human and spirit worlds….

The Greek goddess Athena had the owl, almost always depcited as a Little Owl (Athene noctua) as her sacred bird, and so the owl became associated with philosophy and wisdom…” (Avery, 2016, p. 216).

Rijksmuseum Note About the Painting:

” Aswan fiercely defends its nest against a dog. In later centuries this scuffle was interpreted as a political allegory: the white swan was thought to symbolize the Dutch statesman Johan de Witt (assassinated in 1672) protecting the country from its enemies. This was the meaning attached to the painting when it became the very first acquisition to enter the Nationale Kunstgalerij (the forerunner of the Rijksmuseum) in 1880. ”

Mute Swans

Mute Swans (which are not in fact mute and they occasionally growl) with their pristine white plummage and orange bills, are long lived aquatic birds that seem to epitomize avian love and faithfulness. As the members of a pair display, they move toward each other with their heads down, their two long, curved necks forming the shape of a heart-the the human eye at least” (Avery, 2016, p. 88).

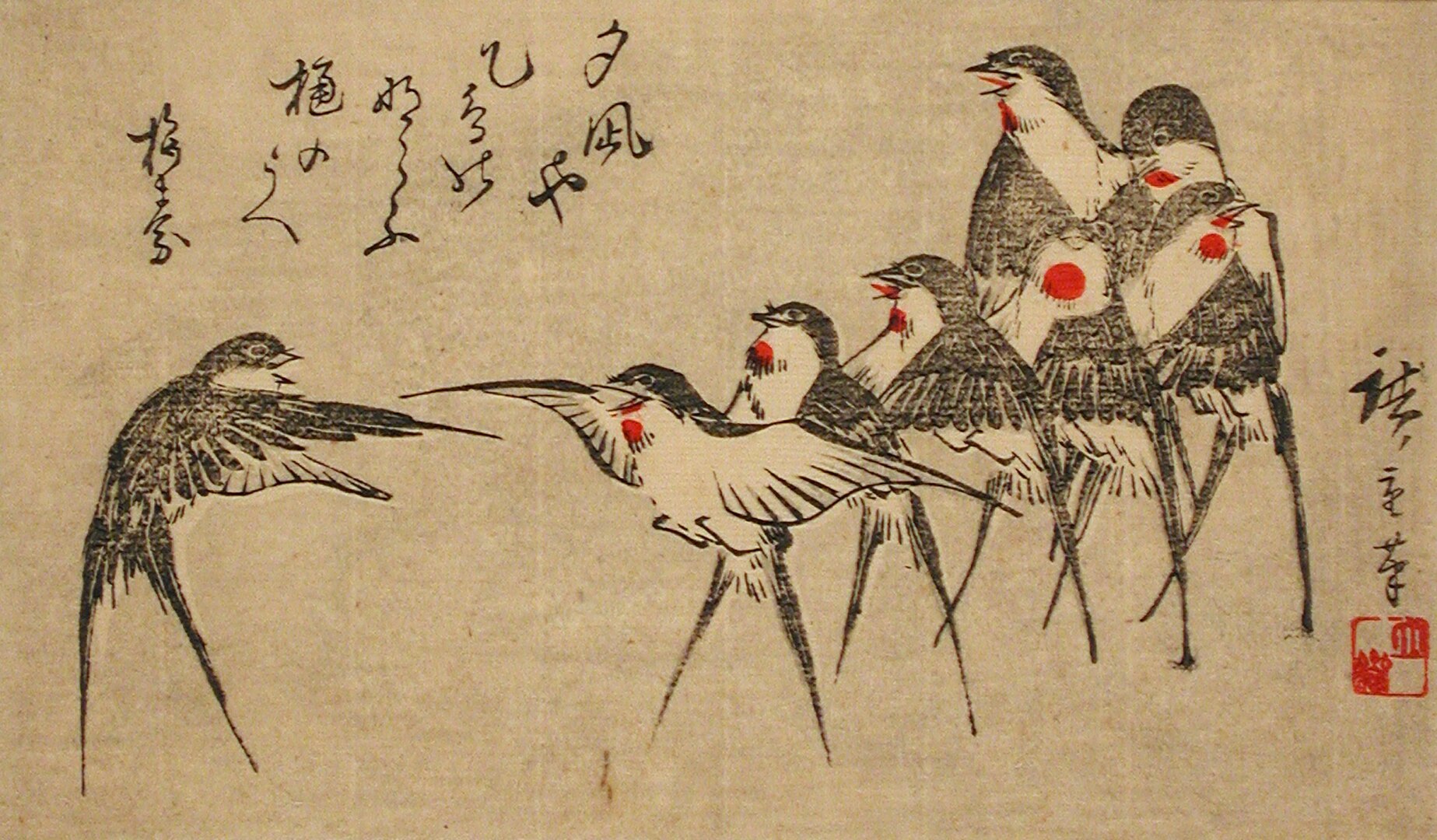

Courtesy: By Utagawa Hiroshige (Japan, Edo, 1797-1858), Utagawa Hiroshige III (Japan, 1843-1894) – Image: http://collections.lacma.org/sites/default/files/remote_images/piction/ma-31781155-O3.jpgGallery: http://collections.lacma.org/node/201293 archive copy, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27270437

Swallows

There are 79 species of swallows and they are noticeable by their swooping flights, long wings, and forked tale. They often nest in man made structures such as bridges and barns.

“Swallows spend more time in flight than any other songbird. The exceptionally long primary feathers of their wings given them a great wing span.

Swallows feed as they fly, making sweeps over fields and marshes picking insects out of the air with their large mouths. Rictal bristles (stiff hairlike feather) around the beak help funnel flying insects into their gape….Swallows are the most widespread of all songbirds, absent only in the Antarctic and the coldest areas of the Arctic. Otherwise they can be found in almost every habitat clear of forests.” (Trudy and Jim Rising, Canadian songbirds and their ways, 1982, p. 76).

Since the publication of this book, many species of swallows have declined in number due to habitat destruction, pollution, and pesticides. For more information on ways to help swallows, please open the link here.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers” by Emily Dickinson

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

The Dalliance of Eagles” by Walt Whitman

The rushing amorous contact high in space together,

The clinching interlocking claws, a living, fierce, gyrating wheel,

Four beating wings, two beaks, a swirling mass tight grappling,

In tumbling turning clustering loops, straight downward falling,

Till o’er the river pois’d, the twain yet one, a moment’s lull,

A motionless still balance in the air, then parting, talons loosing,

Upward again on slow-firm pinions slanting, their separate diverse flight,

She hers, he his, pursuing.

Courtesy: By Rosa Bonheur – Los Angeles County Museum of Art archive copy, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27306715

“The Restored” by Theodore Roethke

In a hand like a bowl

Danced my own soul,

Small as an elf,

All by itself.

When she thought I thought

She dropped as if shot.

‘I’ve only one wing,’ she said,

‘The other’s gone dead,’

‘I’m maimed; I can’t fly;

I’m like to die,’

Cried the soul

From my hand like a bowl.

When I raged, when I wailed,

And my reason failed,

That delicate thing

Grew back a new wing,

And danced, at high noon,

On a hot, dusty stone,

In the still point of light

Of my last midnight. “

(Roethke, Collected Poems. Anchor Books, 1975, p. 241)

To read more poems by Theodore Roethke, please open the Poetry Foundation link here.

“The Eagle” by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ring’d with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

Key Takeaways about Eagles

- “Eagles are large, majestic birds of prey, mostly with strong large beaks for tearing flesh and powerful talons for subduing and killing prey such as small deer, hares, and birds up to the size of Wild Turkeys. However, the species given this name are not all closely related to each other genetically—in fact the taxonomy of eagles is in a state of flux. And there are a few small eagles too, such as the Little Eagle of Australia, which is no larger than a falcon.

- The eagle is commonly known as the king of the birds (despite the claims of the Goldcrest) because, with its size, power, and soaring flight it appears to command the earth from aboe. Eagles also seem to have freedom to go where they like unmolested and without fear. That vision may appeal to many a nation, and eight countries–from the USA (Bald Eagle) to Panama (Harpy Eagle), the Philippines (Philippine Eage), Scotland (Golden Eagle), Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe (all African Fish-eagle)–have an eagle as their national bird. The Bald Eagle because the USA’s national bird in 1782, chosen for its long life, great strength, and majestic looks”(Avery, 2016, p. 218).

- For more information about eagles, please open the link here.

Courtesy: Gift of The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation. “https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.61244.html” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: Dick S. Ramsay Fund. “https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/1244” has No known copyright restrictions.

“A Hummingbird” by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

A route of evanescence

With a revolving wheel;

A resonance of emerald,

A rush of cochineal;

And every blossom on the bush

Adjusts its tumbled head,—

The mail from Tunis, probably,

An easy morning’s ride.

To read more poems about hummingbirds, please open the link here.

For additional learning resources please open the link here.

Courtesy: Purchase, Gift of Albert Weatherby, 1946. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11052” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Metropolitan Museum Art Notes about Martin Johnson Heade

“From 1880 to 1904, Heade, an ardent devotee of natural history, contributed over one hundred letters and articles on hummingbirds and related topics to “Forest and Stream.” Although he was fascinated with the painting of hummingbirds as early as 1862, the majority of his compositions date between 1875 and 1885, after his final trip to South America. The particular species of the hummingbird represented in this painting is the black-eared fairy (Heliothryx aurita) whose habitat is the lowlands of the Amazon basin, as is the passionflower (Passiflora racemosa). Heade, who was familiar with the scientific writings of Charles Darwin, conveys the dualities and interconnectedness between the hummingbird and the passionflowers in this painting.”

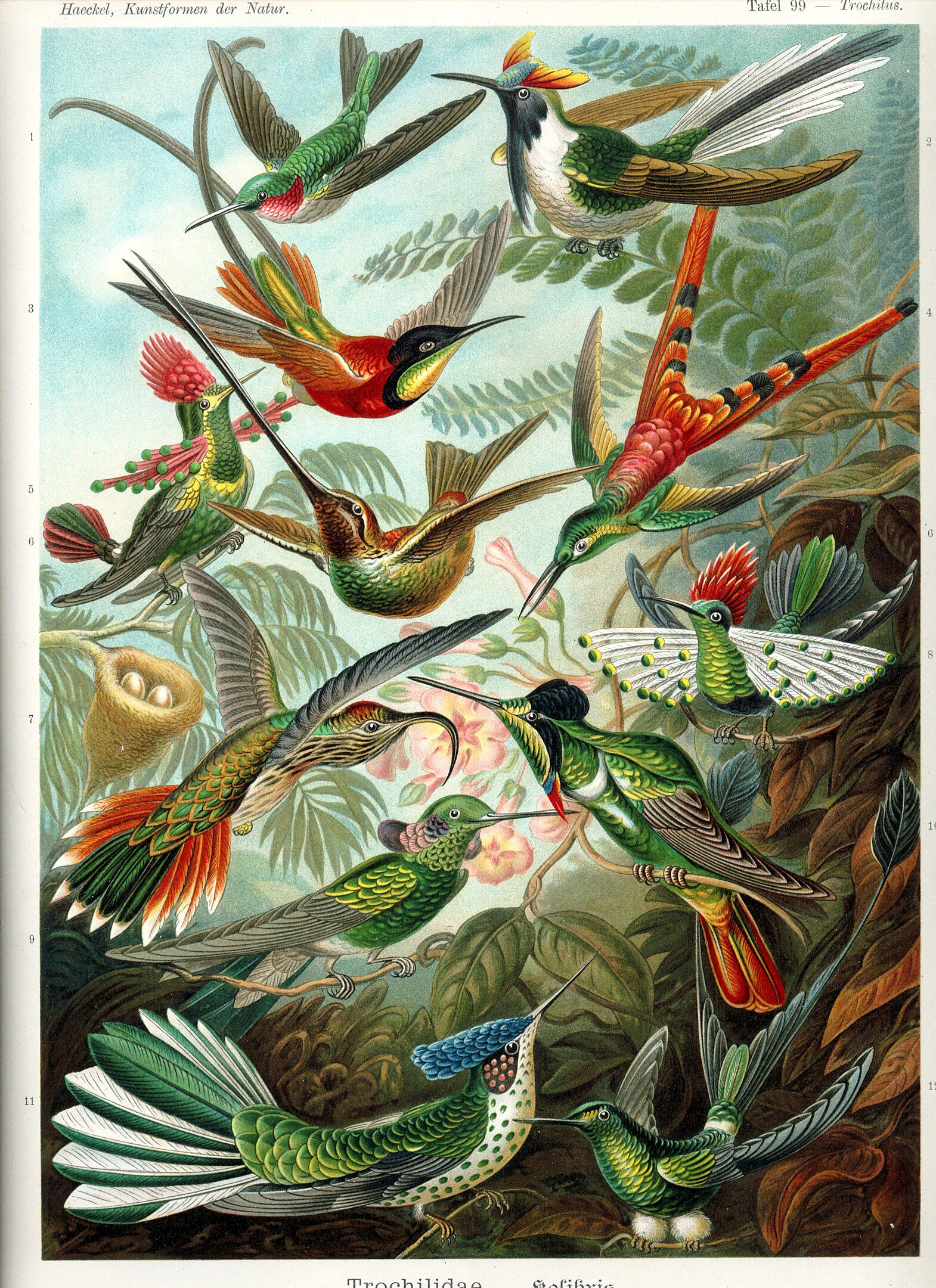

Hummingbirds:

“All of the 340-odd species of hummingbird live in the Americas; they can be found from southern Alask to Tierra del Fuego, though half the species live in the Amazon basin. Hummingbirds are often tiny–the smallest species is also the world’s smallest bird, the Bee Hummingbird, which lives in forests on Cuba and weighs less than 2 g (0.07 oz). There are often very brightly coloured, and hover almost in a blur, like tiny jewels. Their English name, hummingbird, derives from the sound their rapidly beating wings make–in normal flight hummingbirds beat their wings around 50 times per second. Such engergic flight requires large amounts of high-octane fuel, and most hummingbirds feed on the calorie-rich nectar of flowering planets.” (Avery, 2016, p.79).

Source: Avery, M. (2016). Remarkable birds. Thames and Hudson.

Courtesy: By Archibald Thorburn – Bonhams, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14872277

The Fable of Juno and the Peacock by Aesop (6th Century BCE)

“The Peacock made complaint to Juno that, while the nightingale pleased every ear with his song, he no sooner opened his mouth than he became a laughing-stock to all who heard him. The Goddess, to console him, said, “But you far excel in beauty and in size. The splendour of the emerald shines in your neck, and you unfold a tail gorgeous with painted plumage.” “But for what purpose have I,” said the bird, “this dumb beauty so long as I am surpassed in song?” “The lot of each,” replied Juno, “has been assigned by the will of the Fates—to thee, beauty; to the eagle, strength; to the nightingale, song; to the raven, favourable, and to the crow, unfavourable auguries. These are all contented with the endowments allotted to them.””(Wikipedia)

Courtesy: “http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.8740” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: “https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/en/node/226317” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Note about the Artist Melchior d’Hondecoeter

“Melchior d’Hondecoeter’s (1636-1695) specialty of poultry painting was something of a family business. Melchior’s father and grandfather had both been interested in animal painting, and an aunt was married to the painter Jan Baptist Weenix, an Italianist. After studying with his father, d’Hondecoeter was apprenticed to his uncle Weenix, and this gave him an opportunity to develop his technique and use of colour. Besides strikingly realistic scenes of birds, d’Hondecoeter also painted wall hangings with views of buildings and parks. Here, too, birds were usually involved. He was born in Utrecht and died in Amsterdam. Between 1659 and 1663, he worked in The Hague.”

Courtesy: By Bruno Liljefors – https://collectie.rijksmuseumtwenthe.nl/zoeken-in-decollectie/detail/id/436fb301-72ec-5c5c-bcd9-0fd3e9fcd11e, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98347778

“The Wild Swans” at Coole By William Butler Yeats

The North Carolina Parakeet

These beautiful birds were once prolific until they were hunted down to extinction for their long and brilliantly coloured feathers which were used to adorn women’s hats in centuries past. Which other extinct birds are you aware of? Research the factors that contributed to the bird’s extinction. What can be done to protect remaining birds? For more information about the Carolina Parakeet please open the link here.

Courtesy: By John James Audubon – John James Audubon’s “Carolina Parakeets” which is a part of the permanent collection at the New York Historical Society, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=430339

https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-James-Audubon

“The Darkling Thrush” by Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings from broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice outburst among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carollings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

Additional Source: T. Hardy, Poems of the Past and Present, MacMillan & Co. 1919, p. 399).

For more poems by Thomas Hardy please open the links here, here, and here.

For information about teaching poetry please open the links here and here.

Courtesy: By Bruno Liljefors – Stockholms Auktionsverk, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30672946

Courtesy: Gift of Seymour R. Husted Jr. “https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/120428” has No known copyright restrictions.

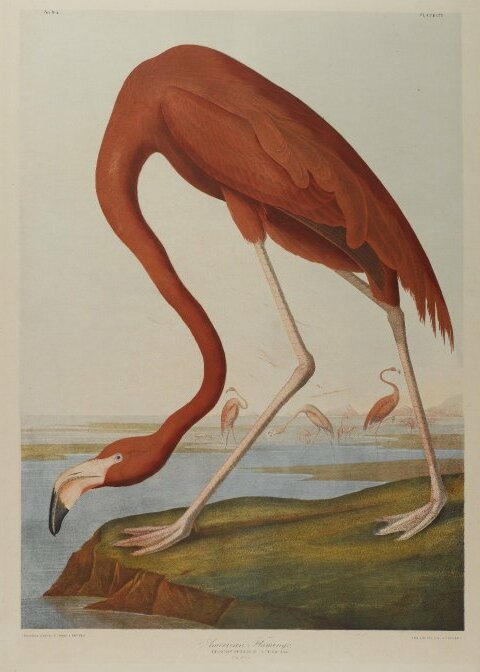

Flamingo:

“All six species of flamingo, four in the New World and two in the Old World, are a shocking pink or red colour and all nest in large colonies. They are striking birds, with their very long legs and necks and curiously shaped bills, and the combination of bright plumage and coloniality make the sight of nesting flamingos one of the avian wonders of the world.

Flamingos are tall wading birds, with the largest species, the Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus) up to 150 com (60 in.) in height. When walking but perhaps more in flight, they appear to be all neck and legs–with a relatively small body and short wings. This is a group of birds that is instantly recognizable from their color and body structure” (Avery, 2016, p. 119).

For more information about flamingos please open the link here.

Flamingo

“A Bird, came down the Walk” by Emily Dickinson

A Bird, came down the Walk –

He did not know I saw –

He bit an Angle Worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,

And then, he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass –

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass –

He glanced with rapid eyes,

That hurried all abroad –

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought,

He stirred his Velvet Head. –

Like one in danger, Cautious,

I offered him a Crumb,

And he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home –

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless as they swim.

Courtesy: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54145” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats

“Hibiscus and Blue Heron” by Theodore Roethke

The heron stands in water where the swamp

Has deepened to the blackness of a pool,

Or balance with one leg on a hump

Of marsh grass heaped above a musk-rat hole.

He walks the shallow with an antic grace.

The greet feet break the ridges of the sand.

The long eye notes them minnow’s hiding place.

His beak is quicker than a human hand.

He jerks a frog across his bony lip,

Then points his heavy bill above the wood.

The wide wings flo but once to lift him up.

A single ripple starts from where he stood.

(The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke. Anchor Books, 1974, p. 14)

“I Heard a Bird Sing” by Oliver Herford

I heard a bird sing

In the dark of December

A magical thing

And sweet to remember.

“We are nearer to Sprin

Than we were in September,”

I heard a bird sing

In the dark of December.

(Additional Source: Felleman, H. (1965) Poems that live forever . Doubleday, p. 389)

Courtesy: By Gustave Moreau – Gustave Moreau, 1826-1898 : catalogue de l’exposition à Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 29 septembre 1998-4 janvier 1999, à Chicago, the Art institute, 13 février-25 avril 1999, à New York, the Metropolitan museum of art, 24 mai-22 août 1999. Paris : Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1996. ISBN 2711835774, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10716788

Symbolism of the Ibis

“The ibis is a group of wading bird whose cultural significance to mankind cannot be overstated. The African Sacred Ibis is among the most important and meaningful symbols in ancient Egyptian mythology.There are a number of different birds belonging to the ibis group spread across the planet. In each place where they dwell, ibis make a lasting impression. Their distinctive decurved bill shape sets them apart from similar wading birds and makes them an instantly recognizable artistic motif. Connected with sacred wisdom, with healing, with art and magic; the ibis is an animal that evokes wonder and awe in humans worldwide. If this exceptional animal speaks to you, then read on to discover the myths associated with the ibis, its role as a spirit animal or totem, and the symbolism of this exceptional bird!”

Courtesy: Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art and Rogers Fund, 2000. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/454011” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes for Black Stork in a Landscape

“The distinctive white neck feathers, purple-streaked wings, and red-tinged beak of this bird identify it as a Woolly-Necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus). The meandering watercourse on the right could be a reference to the riverine areas where such birds are typically found, but the particular fashion in which the landscape is depicted seems to be a distinguishing characteristic of the larger set of bird paintings to which this work belonged. This set may have once comprised over 600 paintings, the patronage of which has been attributed to Claude Martin, who served as superintendent of the arsenal for Nawab Asaf ud-Daula of Lucknow between 1775 and 1800.”

Courtesy: By Roelant Savery – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork http://www.strabrecht.nl/sectie/ckv/00/Blok%201/6%20Ruimte/CKV-f0026.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15417869

“The Darkling Thrush” by Thomas Hardy

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-grey,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

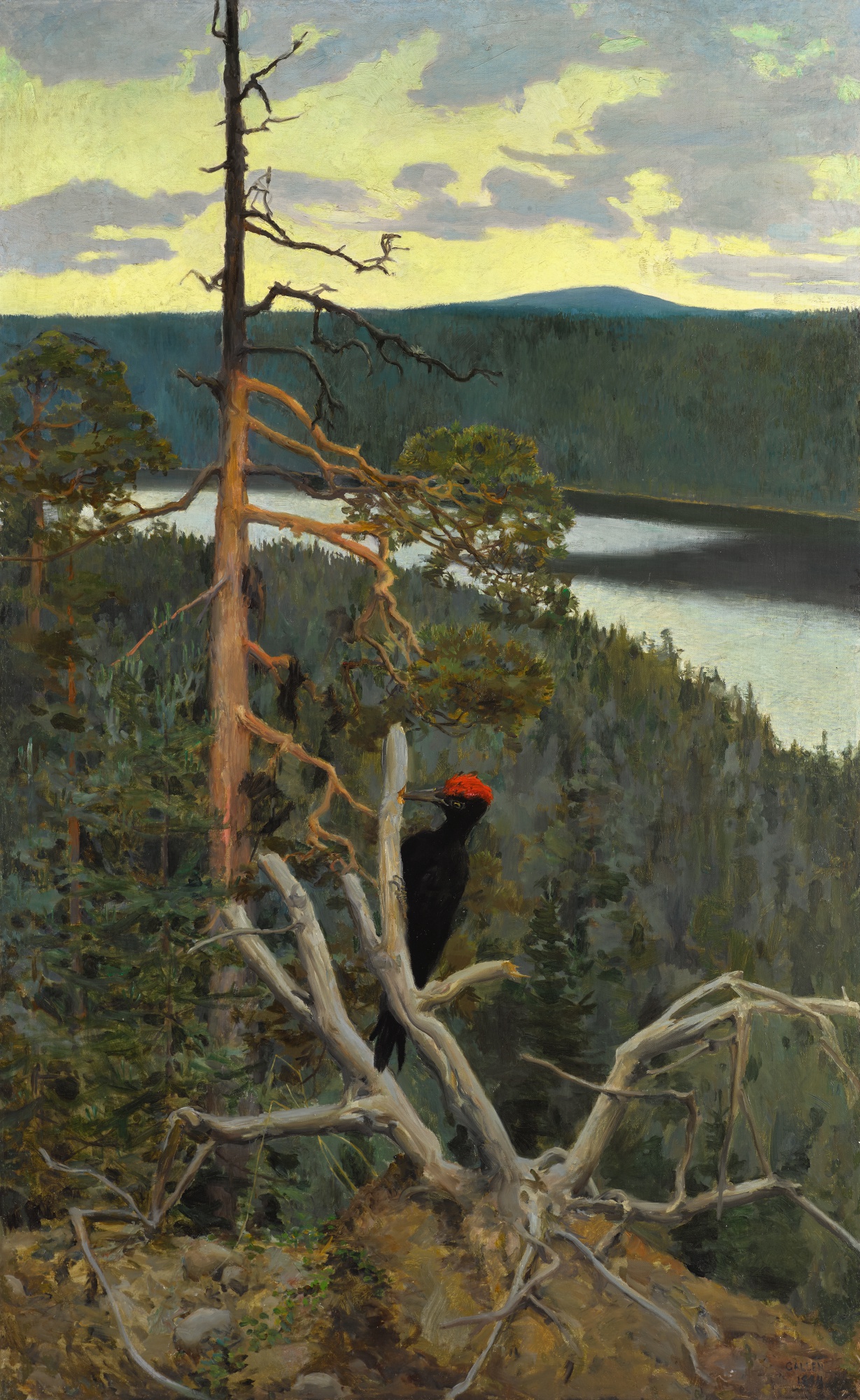

Courtesy: By Akseli Gallen-Kallela – Sotheby’s https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/coming-to-auction-a-finnish-masterpiece-combining-natural-beauty-with-national-pride, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86673474

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, to whom the Musée d’Orsay devoted an exhibition in 2012, is Finland’s major artist, the only one to have achieved truly international recognition in his lifetime, one of the essential authors of a Finnish national culture in the midst of a revival, at a time of struggle for an independence gained from Russia in 1917.

The Woodpecker by Elizabeth Madox Roberts

The woodpecker pecked out a little round hole

And made him a house in the telephone pole.

One day when I watched he poked out his head

And he had on a hood and a collar of red.

When the streams of rain pour out of the sky,

And the sparkles of lightning go flashing by,

And the big, big wheel of thunder roll,

He can snuggle back in the telephone pole.

“The Woodpecker” by Emily Dickinson

His bill an auger is,

His head, a cap and frill.

He laboreth at every tree, —

A worm his utmost goal.

OWLS

Courtesy: Finnish National Gallery / Tero Suvilammi. “https://www.kansallisgalleria.fi/en/object/525374” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: Gift of Mrs. Walter B. James. “https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.32262.html” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: The Minnich Collection The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund, 1966. “https://collections.artsmia.org/art/75136/snowy-owl-edward-lear” is licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0.

“I rejoice that there are owls. Let them….do their hooting. It is a sound admirably suited to swamps and twilight woods which no day illustrates, suggesting a vast and undeveloped nature which men have not recognized. They represent the stark twilight and unsatisfied thoughts which all have. All day the sun has shone on the surface of some swamp, where the single spruce stands hung with usnea lichens, and small hawks circulate above, and the chickadee lisps amid the evergreens, and the partridge and rabbit skulk beneath; but now a more dismal and fitting day dawns, and a different race of creatures awakes to express the meaning of Nature there.” (Thoreau, Walden, 2021 Arcturus Ed., p 121).

“Second Song to the Same” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

First printed in 1830.

1

Thy tuwhits are lull’d I wot,

Thy tuwhoos of yesternight,

Which upon the dark afloat,

So took echo with delight,

So took echo with delight,

That her voice untuneful grown,

Wears all day a fainter tone.

2

I would mock thy chaunt anew;

But I cannot mimick it;

Not a whit of thy tuwhoo,

Thee to woo to thy tuwhit,

Thee to woo to thy tuwhit,

With a lengthen’d loud halloo,

Tuwhoo, tuwhit, tuwhit, tuwhoo-o-o….

Courtesy: By Leon Wyczółkowski – artlibra.pl, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84144437

Courtesy: By http://www.acnatsci.org/library/collections/lear/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7212432

“The Owl” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

When cats run home and light is come,

And dew is cold upon the ground,

And the far-off stream is dumb,

And the whirring sail goes round,

And the whirring sail goes round;

ALone and warming his five wits,

The white owl in the belfry sits.

When merry milkmaids click the latch,

And rarely smells the new-mown hay,

And the cock hath sung beneth the thatch

Twice or thrice his roundelay,

Twice or thrice his roundelay;

Alone and warming his five wits,

The white owl in the belfry sits.

“The Tree, the Bird” by Theodore Roethke

Uprose, uprose, the stony fields uprose,

And every snail dipped toward me its pure horn.

The sweet light met me as I walked toward

A small voice calling from a drifting cloud.

I was a finger pointing at the moon,

At ease with joy, a self-enchanted man.

Yet when I sighed, I stood outside my life,

A leaf unaltered by the midnight scene,

Part of a tree still dark, still, deathly still,

Riding the air, a willow with its kind,

Bearing its life and more, a double sound

Kin to the wind, and the bleak whistling rain.

The willow with its bird grew loud, grew louder still.

I could not bear its song, that altering

With every shift of air, those beating wings,

The lonely buzz behind my midnight’s eyes;

How deep the mother-root of that still cry!

The present falls, the present falls away;

How pure the motion of the rising day,

The white sea widening on a farther shore.

The bird, the beating bird, extending wings—

Thus I endure this last pure stretch of joy,

The dire dimension of a final thing.

(From The collected poems of Theodore Roethke Anchor Books. 1974/1975, p. 240.

Courtesy: Linn Ahlgren / Nationalmuseum. “https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=18654&viewType=detailView” is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Courtesy: By Archibald Thorburn – Bonhams, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14872234

Bird Illustrations from Books and Ornithology Texts

Courtesy: By Edward Lear – Typ 805L.32 (A), Houghton Library, Harvard University, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34154154

Courtesy: Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Donald C. Gallup, Yale BA 1934, PhD 1939. “https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:5422” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Donald C. Gallup, Yale BA 1934, PhD 1939. “https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:5424” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“Dalmatian Pelican. Pelecanus crispus, Feld. A bird of such striking magnitude as the present having so long escaped observation even on the shores of Europe, what may we not expect from those more distant countries to which the scrutinizing eye of the naturalist has seldom penetrated ? Although this species has been introduced to the notice of the scientific within the last few years only, it has doubtless long abounded where it is now found. The specimen from which our figure is taken was sent us by Baron de Feldegg, and was one of twenty-four killed by him on the shores of Dalmatia. In the letter which accompanied this specimen the Baron thus writes : The first example of this bird that came under my notice was shot by myself in the year 1828 in Dalmatia, and was sent to the Imperial Cabinetin Vienna. Two years after this, Messrs. Ruppell and Kittlitz met with this species in Abyssinia, where,however, it would appear to be very scarce, as those gentlemen procured only a single specimen.”

“Pelican on the Sea of Galilee” (Excerpt) by Lydia Sigourney

“A single pelican was floating there; like myself, he was alone.”—Stephens’s Incidents of Travel.

Lone bird, upon yon sacred sea,

Dimpling with solitary breast

The silent wave of Galilee,

Where shall thine oary foot find rest?

Hast thou a home mid rock or reed

Of this most desolate domain,

Where not one ibex dares to feed,

Nor Arab tent imprints the plain?

What know’st thou of Bethsaida’s gate?

Or old Chorazin’s desert bound?

What heed’st thou of Capernaum’s fate,

Whose shapeless ruins throng around?

Once, when the tempest’s wing was dark,

A sleeper rose and calm’d the sea,

And snatch’d from death the fragile bark—

Here was the spot, but who was he?

He heard the surge impetuous roar,

And trod sublime its wildest crest,

Redeemer! was yon watery floor

Thus by thy glorious feet impress’d?

Oh, when each earthly hope and fear,

Each fleeting loss, each fancied gain,

Shall to our death-dimm’d sight appear

Like the lost cities of the plain,

Then may the soul, enslaved no more,

Launch calmly on salvation’s sea,

And part from time’s receding shore,

Lone, peaceful pelican! like thee.

Courtesy: By Thorburn, Archibald – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/pageimage/43051602, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44643616

“The King Fisher” by Maurice Thompson

He laughs by the summer stream

Where the lilies nod and dream,

As through the sheen of water cool and clear

He sees the chub and sunfish cutting sheer.

His are resplendent eyes;

His mien is kingliwise;

And down the May wind rides he like a king,

With more than royal purple on his wing.

His palace is the brake

Where the rushes shine and shake;

His music is the murmur of the stream,

And that leaf-rustle where the lilies dream.

Such life as his would be

A more than heaven to me:

All sun, all bloom, all happy weather,

All joys bound in a sheaf together.

No wonder he laughs so loud!

No wonder he looks so proud!

There are great kings would give their royalty

To have one day of his felicity!

To read more nature poems, please open the link here.

“Nature the Gentlest Mother” by Emily Dickinson

Nature the gentlest mother is

Nature the gentlest mother is,

Impatient of no child,

The feeblest of the waywardest.

Her admonition mild

In forest and the hill

By traveller be heard,

Restraining rampant squirrel

Or too impetuous bird.

How fair her conversation

A summer afternoon,

Her household her assembly;

And when the sun go down,

Her voice among the aisles

Incite the timid prayer

Of the minutest cricket,

The most unworthy flower.

When all the children sleep,

She turns as long away

As will suffice to light her lamps,

Then bending from the sky

With infinite affection|

An infiniter care,

Her golden finger on her lip,

Wills silence everywhere.

“To a Skylark” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Courtesy: By Ernst Haeckel – Kunstformen der Natur (1904), plate 99: Trochilidae (see here, here and here and Biodiversity Heritage Library), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=605426

Courtesy: By Ohara Koson – Woodblock print circa 1910 by Ohara Koson (1877-1945), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36393309

Courtesy: By Briton Rivière – 1.Art UK2. Art UK: entry a-saint-from-the-jackdaw-of-rheims-183448, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26056027

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Public domain. First published by Wiley and Putnam, 1845, in The Raven and Other Poems by Edgar Allan Poe)

To view Gustave Doré’s artistic interpretations of Poe’s famous poem, please open the Project Gutenberg eBook link here.

To view more illustrated books by Gustave Doré (1832-1883), please open the link here.

Ravens

“Anyone who watched ravens would soon learn that these birds are loyal and considerate mates and devoted parents. You also learn that young raven nestlings squawk for food with louder and longer cries than almost any other species you could name, so they were the example that came immediately to mind when the writers of Job 38:41 and Psalm 147:7-9 wanted to call up a reminder of how God the Father provides for all small wildings, giving each its food-not with its own hand but by providing parent ravens–as he does almost all wild parents, beast or bird—with the instincts to choose the food best suited to infant needs, to bring such food again and again as long as the opened beaks and lifted voices reveal hunger’s need.”-Gibson, 2005, p. 45.

*The Norse God Odin (“Wotan”-all Powerful) had two ravens by his side: one was named Huginn (Thought) and the other Memory (Muninn). Odin’s “raven knowledge” was thought to come from the information that Huginn and Muninn acquired in their daily scoping of information from all parts of the world. To read more about Odin and his ravens please open the link here.

Courtesy: Charles Stewart Smith Collection, Gift of Mrs. Charles Stewart Smith, Charles Stewart Smith Jr., and Howard Caswell Smith, in memory of Charles Stewart Smith, 1914. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54645” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Sparrows:

The House Sparrow may have originated in the Tigris and Euphrates region of the Middle East in the development of agricultural society (about 5000 BCE). As agriculture expanded into Europe, the House Sparrow followed. The House Sparrow found its way to North America in 1853.

“The sparrows that finally became successfully established were the descendants of 50 released in a Brooklyn cemetery in 1853. Impressed by how well these sparrow did, other people who liked the little brown bird brought them to their cities as well. During the next 333 years, House Sparrows expanded on their own, spreading to 35 states in the US and to Canada. At the turn of the century just before horses were replaced by cars, they reached their greatest numbers. By 1915, they spread to the West Coast and became established there. In North America, House Sparrows are now found nearly everywhere people have buildt cities, even in the Far North in Churchill, Manitoba, on the coast of Hudson Bay where they live near grain elevators feeding on fallen grain. Since 1800, they have also expanded their range in Europe and have been introduced to places such as South America, New Zealand, and Hawaii. Today, the House Sparrow is one of the most widespread species in the world.” (Trudy and Jim Rising, Canadian songbirds and their ways (with paintings by Kathryn DeVos-Miller, Tundra, 1982, p. 111).

*Since the publication of this book, many species of sparrows have declined due to habitat destruction and pollution. Since 1996, Manitoba’s Baird’s sparrow has been listed as endangered.

To read more about what you can do to help protect birds please open the Canadian Wildlife Federation link here.

For additional information please open this link:Protecting Avian Biodiversity..

Courtesy: By Ohara Koson – Catalogue, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46475500

T”he Sparrow” by Paul Laurence Dunbar

A little bird, with plumage brown,

Beside my window flutters down,

A moment chirps its little strain,

Ten taps upon my window–pane,

And chirps again, and hops along,

To call my notice to its song;

But I work on, nor heed its lay,

Till, in neglect, it flies away.

So birds of peace and hope and love

Come fluttering earthward from above,

To settle on life’s window–sills,

And ease our load of earthly ills;

But we, in traffic’s rush and din

Too deep engaged to let them in,

With deadened heart and sense plod on,

Nor know our loss till they are gone.

Paul Laurence Dunbar, born in 1872 was one of the first African American poets to gain national recognition for his poetry and prose. He died at 33 but he left a legacy that has inspired many writers and artists.

For more information about Paul Laurence Dunbar please open the link here.

Paul Laurence Dunbar: A Tribute (Reprinted from TALENT, March, 1906.)

“Because I had loved so deeply, Because I had loved so long, God in His great compassion Gave me a gift of song.”-Paul Laurence Dunbar

Because I have loved so vainly, And sung with such faltering breath, The Master in infinite mercy, Offers the boon of Death.” -Paul Laurence Dunbar

“During the long years of suffering, when he stood facing the inevitable, Paul Laurence Dunbar rarely gave expression to any but hopeful, joyous sentiments. The philosophy of his last year seems to have been the lines quoted above. Eager to say what was in his heart before he was called from his labors, modestly denying that he had succeeded, struggling on to try just once more, he kept busily at work, singing his love songs to the world. That he loved deeply no student of his poetry can doubt.

Paul Laurence Dunbar loved nature in all her common manifestations; he loved people in all their moods. Life to him was joy. He seemed to look upon the world about him with the delight of one who has never seen it before, as one who took it for what it appeared to be, a joyous manifestation of eternal love. His poetry is the expression of an awakened soul, that coming into a new possession finds it a sweet dream come true, a rare delight, a lasting pleasure. Thus he lived and sang. He was never physically strong, and during the last six or seven years he knew that death must come soon, but to the very last he sung his songs of good cheer. For him every night had a coming dawn, a light shone on every dangerous coast. He wrote about common things, common people, and the common God. Like a lark uncon scious of the songs of others, he sang for the pure joy of singing, caring not that his themes had been written about before; these songs were his, were the expression of his own nature, and it was a delight to give them utterance.”

“Song” by Christina Rossetti (1830-1894)

Two doves upon the self-same branch

Two lilies on a single stem

Two butterflies upon one flower:–

Oh happy they that look on them.

Who look upon them hand in hand

Flushed in the rosy summer light;

Who look upon them hand in hand

And never give a thought to night.

(from: J.Marsh (1985) The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, St. Martin’s Press, p. 26.)

Courtesy: By Elliot, Daniel Giraud – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/pageimage/44792765, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44588907

Courtesy: By Elliot, Daniel Giraud – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/pageimage/44792727, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44588930

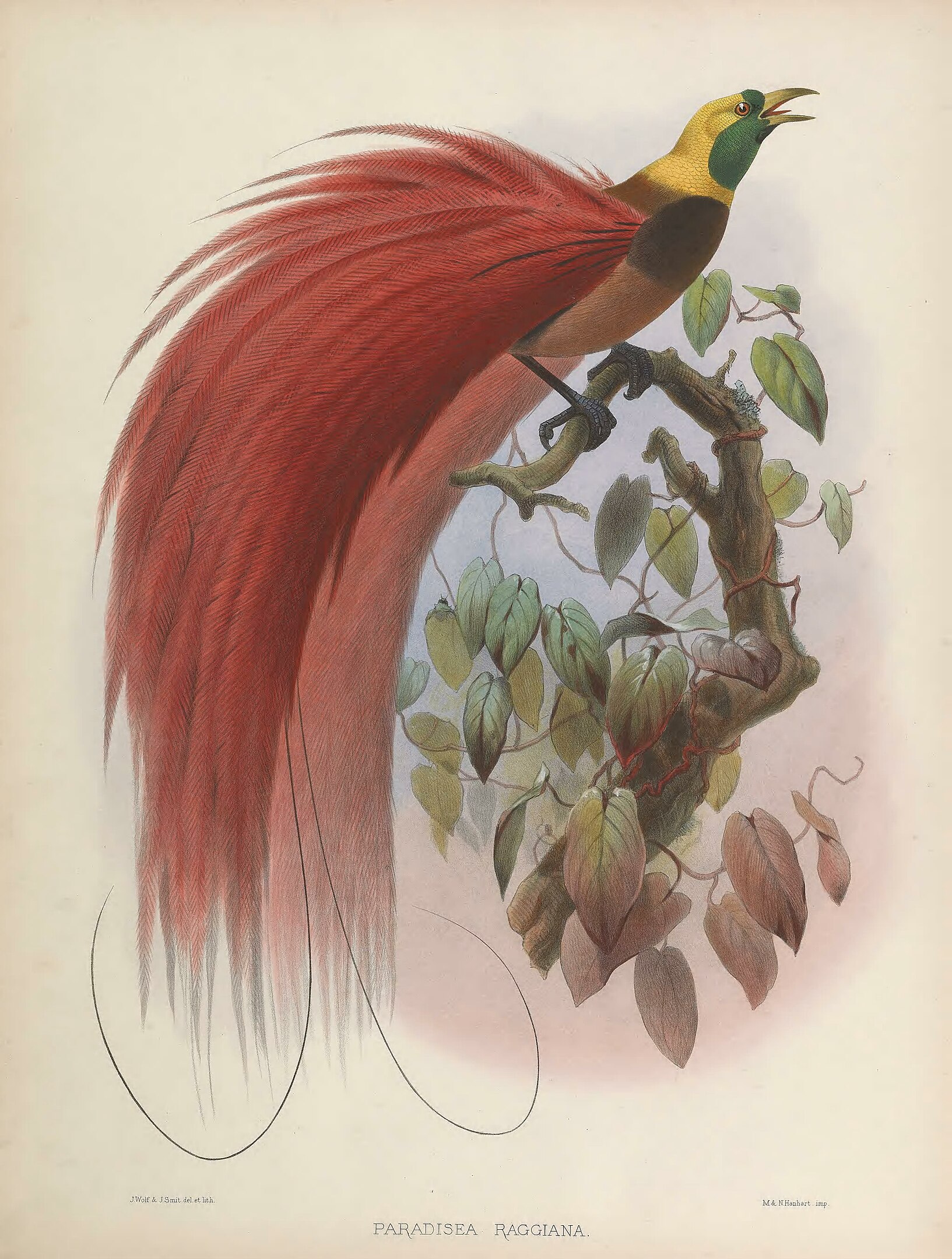

Birds of Paradise

“The birds of paradise comprise about 40 species of crow-sized birds, most of which are found in Papua New Guinea…As in all birds of paradise, the male is very striking, while the plummage of the female is duller, as she needs to be camouflaged when incubating the eggs and caring for the young. The males have no such constraint, as their role is limited to copulation with females and they play no part in parental care. They have therefore developed a spectacular range of feather in dazzling shapes and colours, as well as extraordinary mating displays…

The feathers of birds of paradise have long been highly prized and used as adornments and in rituals in their native lands. Prepared skins, lacking wings and especially feet, were often traded, and some found their way to Europe in the sixteenth century. These beautiful, unfamiliar, and apparently wingless and footless birds, aroused great interest and scientific specultation. It was thought perhaps that they floated high in the sky, maybe in Paradise itself, where they fed in the clouds. The great Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus named the Greater Bird of Paradise Paradisaea apoda-apoda meaning ‘without feet.'” (Avery, 2016, pp. 99-100).

To read more about the Birds of Paradise please open the link here.

“The Birds of Paradise” by John Peale Bishop

I have seen the Birds of Paradise

Afloat in the heavy noon,

Their irised plumes, their trailing gold,

Their crested heads, like flames grown cold;

They rose and vanished soon.

Strange dust is blown into mine eyes;

I doubt I shall ever see

Their lightly lifted forms again,

Their burning plumes of holy grain,

And this is grief to me.

Additional Sources:

Gould, J. (1804-1881) (British Ornithologist). The Birds of Europe in Five Volumes. For the illustrated volume of J. Gould’s ground breaking book on birds please open the link here.

Biodiversity Heritage Library Dictionary of Birds