Chapter 5: Transformative Learning Through Arts-Based Pedagogies and Transcultural Connections

Each work of art can provide us with insights into the life experiences, social, philosophical, and spiritual traditions of individuals and cultures. Themes such as love, beauty, perseverance, courage, friendship, loneliness, and resilience can be explored and analyzed through art of all mediums. Artwork can be a bridge that enables learners to understand characters and themes across historical and cultural contexts. Visual images can be a new window that can help expand a learner’s interpretation and analysis of a literary or non-fiction work. Early photographs from 19th Paris as well as Impressionist art can help students visualize the setting for Guy de Maupassant’s classic short stories like The Jewels and The Necklace (see Chapter Eight of this volume). The Jazz Age setting of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short stories A Diamond as big as the Ritz and The Great Gatsby can be illuminated by innovative artists like Gustav Klimt and the designer Charles Renee MacIntosh who influenced the designs and art of the 1920’s and 1930’s along with photographs of the 1920’s and iconic images of art, fashion, and design from that time period such as paintings by Tamara De Lempicka, Georgia O`Keefe, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, and many others.

To read an essay that reinterpretsThe Kiss by Gustav Klimt, please open the link here.

Paul Klee (1879-1940), Rot/grn orange/blau (Red/Green/ Orange/Blue), 1919. Private Collection. “https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125868296” by Christies is licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0.

A new style of painting and design emerged through experimentation and exploration. Experimentation with colour, shape, and perspective can be reflected in creative writing projects connected to visual art. These might include learners writing a short story or a dialogue involving the characters portrayed in a particular painting. This process can be reversed to help a learner appreciate a complex text. Nuances of emotional expression from portraits and scenes from a photograph or painting can enrich understandings of complex texts. Jordan and DiCicco (2012) draw upon numerous studies to assert that purposeful study and integration of visual arts in English education “results in higher motivation and increased attendance, increased creativity, heightened ability to produce imagery, and improved communication skills” (p.29). Jordan and DiCicco (2012) further suggest that students’ critical reading and reasoning skills can be strengthened by studying visual art. Sharing one’s interpretation with other students is another way to invite perspective taking:

Just as literary analysis often involves making an argument about themes, concepts, and forms of or between literary works, interpreting art asks the viewer to make similar arguments to interpret the work…To analyze a painting, a viewer must use background, knowledge of the content and the artist; comprehend the overall meaning of the painting by understanding the colors, lines, symbols, etc. (much like a reader must decode a text by understanding the letters, words, sentences, and ideas of a text). (Jordan and DiCicco, 2012, p. 30).

Creative approaches to literacy learning would tap into the myriad of resources that visual arts can provide. A critical insight into art and architectural forms can also sharpen learners’ insights into cultural, social, and political analysis. Elliot Eisner (2002) suggests that research into visual arts can help students become more aware and observant of the economic, structural, ergonomic, and aesthetic dimensions of design. Artistic images can complement the teaching of a particular text by providing valuable background knowledge. In reading The Grapes of Wrath or Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, students can build background knowledge by researching the works of photographer Dorothea Lange; her photograph Destitute Pea Pickers in California, Mother of Seven Children, Age Thirty-Two, Nipomo California, a work that came to be simply known as Migrant Mother taken in 1936 reflects the desperation and worry of many families who experienced tremendous hardship and tragedy during the Great Depression. Further analysis also reveals conflicting information about the famous photograph, the use of photography as propaganda, and the situation of Florence Thompson, the woman in the photograph. Photographs like Migrant Mother were used by the United States Department of Agriculture to draw the world’s attention to the importance of agriculture and the dust bowl drought to generate funding to help farm workers and their families.

Graphic novel versions of any classical or contemporary texts make use of compelling visual images that portray the essential elements of fiction that include setting, plot, characters, conflict, theme, and atmosphere. By including more visual images, teachers are creating a dynamic learning climate that invites greater participation, choice, and opportunities for insight and understanding. Poetry and visual images that are presented side by side can express stories, voices, impressions, and expressions, notes Jan Greenberg (2001). Poetic when complemented with visual art, can enrich creative responses to literature among students. Emotional empathy and self-awareness can be strengthened when learners have an opportunity to explore poetic and visual texts that present universal themes. Multi-modality literary learning can be encouraged when poetry and images are used in a way to encourage creative self-expression. Jan Greenberg’s Side by side (2001) presents new poems and art from thirty-three countries and six continents. Each poem is presented in the original language and with the English translation. Her book conveys universal themes connected to social justice and peace building. Kenneth Koch and Kate Farrell’s Talking to the sun: An illustrated anthology of poems (1985) for young people juxtaposes well known and newer poems with stunning art, photography, and sculpture from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In Images of nature: Canadian poets and the group of seven compiled by David Booth (1995) asserts that as you view the paintings and read the poems by writers like Leonard Cohen, Margaret Atwood, and Earl Birney, a greater appreciation for the vast beauty and power of the Canadian land emerges. Books such as these that connect visual images and poetry can be a catalyst for students to create their own books of art, mixed media, poetry, and related texts. New perspectives and vision for learning open up with foundational texts that provide rich examples. Art can also be used to provoke, trouble, and challenge in reflecting on difficult issues (Magro, 2022).

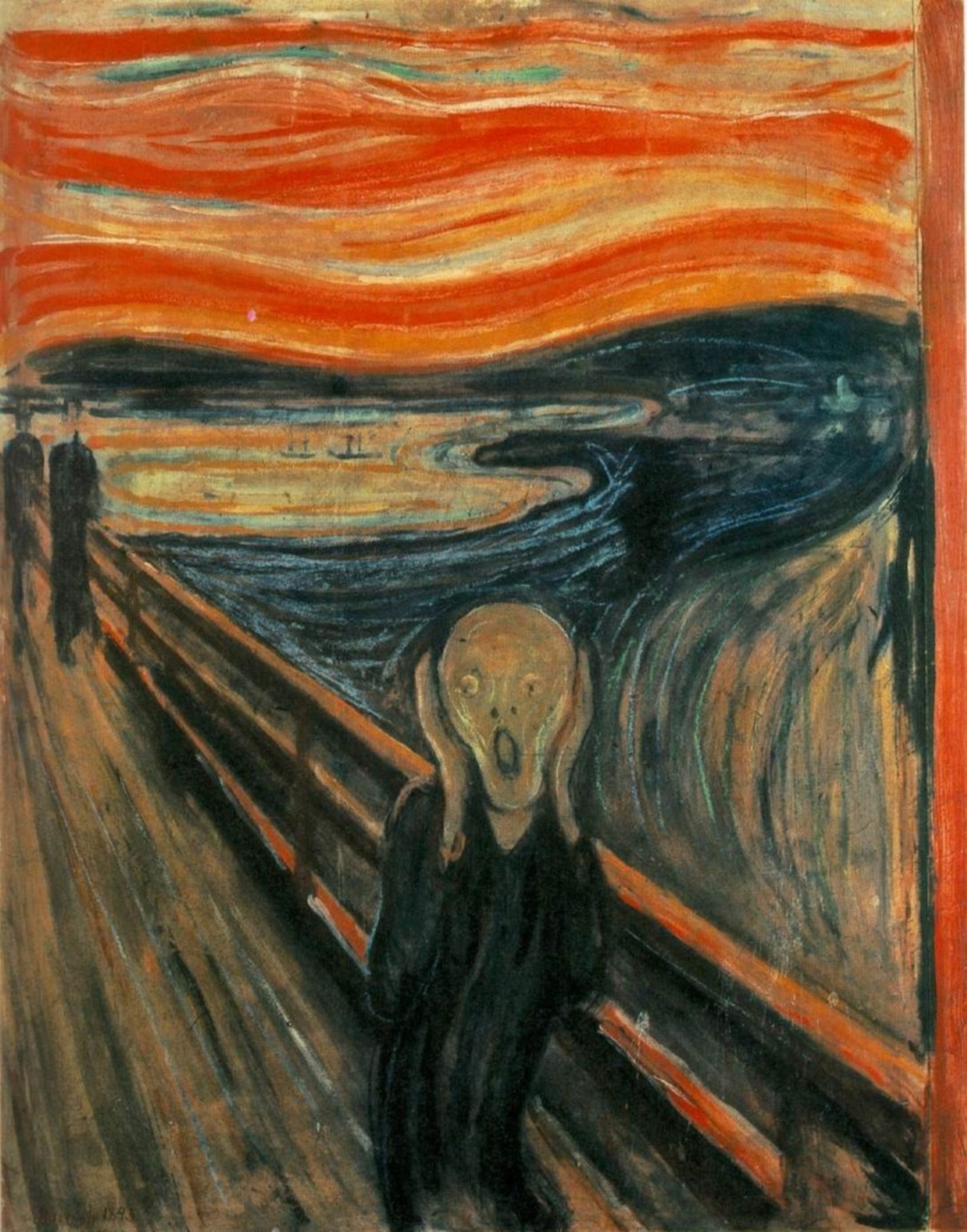

Canadian Indigenous painter Kent Monkman (1965-) emphasizes that art should not only be about presenting images of beauty, but rather, it should function to challenge and critique social systems. Drawing on the panoramic paintings of Caravaggio, Delacroix, Rubens, and Picasso, Monkman recasts the visual art of the “great masters” with an aim to provoke critical thinking about the impact that colonialization had on Canada’s Indigenous people and the natural environment (Bascaramurty, 2017). Monkman’s (2018) art exhibit “Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience” can be a catalyst that opens difficult conversations about racism, cultural genocide, and the resilience of Indigenous people in Canada. His work “The Scream” portrays the trauma of families disrupted when their children were forcibly removed from their homes to attend residential schools. Monkman’s compelling murals speak to the flawed foundational myths surrounding Canada’s historical foundations. Without acknowledging the violation committed towards the natural environment and the Indigenous Peoples, truth, reconciliation, and healing cannot occur.

(To view Kent Monkman’s art please open the links here and here.

Transcultural Connections: Art and Related Texts to Bridge Cultural Awareness and Insight

“Education is a process of learning how to become the architect of our own education. It is a process that does not terminate until we do.” (Elliot Eisner, 2002)

An ethnographic approach to studying literature and non-fiction can encourage learners to gain valuable insights into other cultures. Themes such as discrimination and oppression can be explored from an interdisciplinary perspective. Arias (2008) writes that “ethnography puts students in the position to see themselves as products of culture, within the context of cultural signs. Ethnography also encourages students to question truths about human nature, continually asking students to be aware of their subjective and objective selves” (p.2). Ethnographic approaches to international literature and non-fiction challenges students not to make generalizations about the ‘other.’ In teaching a text like E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, Arias encouraged his students to analyze a “multiplicity of interpretations regarding the mysteries of the human heart, the limitations of language, and the struggle for genuine connection across the barriers of race, religion, culture, class, gender, sexual orientation, and language” (2008, p.94).

Empathy is more likely to develop when learners are given an opportunity to identify with the struggles that a character may be going through regardless of colour, geographic distance, and ethnic background. Tara Westhover’s memoir Educated (2018) is a powerful personal narrative describing the author’s tenacity and the pathway that enables her to rise above the adversities of growing up isolated from mainstream society in the mountains of Idaho. Her survivalist parents forbade formal education, medical treatment, religious freedom, personal self-expression, and “modern” influences. Westhover broke away from her oppressive environment and through perseverance and self-direction, created a new life for herself. These stories can encourage intercultural empathy and global citizenship awareness. Rich learning experiences emerge when students become cultural ethnographers, researchers and writers. Critical literacy encourages learners to “question truths about human nature, continually asking [them] to be aware of their subjective and objective selves” (Arias, 2008, p. 21). In an ethnographic approach to teaching literacy, students become cultural anthropologists, gathering information by observing and writing about the cultural artifacts they have collected. These artifacts might include: magazine articles, interviews, films, music video, artistic expression, music, etc. Creative learning invites experimentation, a spirit of playfulness, and invention. When we draw upon the artistic world to re-configure a new pathway for teaching literacy skills in their myriad form, we are working toward a transformative process that can encourage both personal and social agency. Storytelling, visual art, and teaching international texts from interdisciplinary and ethnographic perspectives can invite learners to think in more imaginative ways. Rigid boundaries between subjects disappear and a more imaginative and rich curriculum can emerge.

There are many similarities between arts based ways of knowing, creative learning and transformative learning. Integrating visual literacies into the ELA curriculum can enrich learning experiences. Content areas such as psychology, sociology, media studies, history, and world issues can also be enriched when visual images are integrated in teaching. There is an emphasis on multi-modal, embodied, spiritual, and affective learning. Cognitive development enables individuals to consider alternative perspectives. Learning contexts provide multiple opportunities for students to gain experiences and skills that can advance their knowledge in personal and practical ways, across the curriculum. Pre-existing beliefs and assumptions are challenged and through reflection, dialogue, and the exploration of alternative perspectives, revised meaning structures lead to paradigm shifts and revised meaning structures (Cranton, 1994, p. xii). Transformative learning is a deeper level learning process that involves critical reflection and perspective taking.

Educators can encourage a cross-cultural appreciation of art by introducing art from different geographical, social, and cultural backgrounds. Poems, folktales, myths, and legends can be integrated with artistic creations from different cultures. Represented by a painting, weaving, rug, bowl, or housing structure, art can tell a story about a particular culture and lived experience. Art from one culture can intrinsically influence the style and form of art in another culture. By exploring art from many cultures, students can gain valuable cross-cultural insights. In Calliope’s Sisters, Richard L. Anderson (1989) draws upon psychology, cultural ethnography, art history, and anthropology to present a comparative analysis of art from Asia, Africa, North and South America, and the far north. A “deeper and more critical understanding of Self” can emerge through cross cultural ways of knowing. He writes that there are obvious and nuanced reasons for learning about different ways of knowing and different lifestyles:

By looking at others, we gain new perspectives on ourselves—on the society that bore us and on the psychological terrain that constitutes our own minds. If we seek to understand ourselves, perhaps trying to bring to conscious formulation a vague and unconscious feeling of dissatisfaction, the study of anthropology becomes a reflexive endeavor, an effort to find secure moorings for our own social or personal cosmos (Anderson, 1989, p. 200).

Anderson identifies four main functions of art in the Western world. These include: Mimetic functions which highlight the relationship between the work of art and some material object that “imitates” the object in real or idealized way. The pragmatic function of art has a “practical” value in society; religion art had the goal of enriching the spiritual life of individuals. Political art also has a pragmatic function. Artistic styles like the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and Expressionism exemplify emotionalist theories of art. Art conveys the inner psychological realm of experience. Throughout the books, you will have an opportunity to see art that reflects many different functions. Art may also integrate different forms and functions; no one category would apply. Individuals also respond to art is very unique ways. Formalist theories of art look at the style of the art work itself; a significant form based on an artistic medium like marble, bronze, or clay is used to produce a unique work. (Anderson, p. 202).

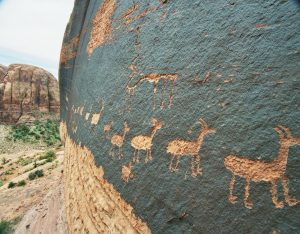

The following art images reflect diverse artistic styles that can be further explored through social, cultural, and historical lenses.

Courtesy: By No machine-readable author provided. Tibicena~commonswiki assumed (based on copyright claims). – No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1097495

Petroglyphs are rock engravings have been chiselled into rocks/stones have been found in all parts of the world with the exception of Antarctica; many Indigenous cultures continued to create them until contact with Western culture. Featuring fantastical animals, humans, human like creatures or anthropomorphs. hunting tools, geometric patterns, cosmic symbols, and motifs, petroglyphs and rock art have been dated between several hundred years to 7,000 and 20,000 years old. Anthropologists and archaeologists have suggested that petroglyphs and petrographs (rock paintings) are a type of “symbolic language” that reflect social, cultural, and spiritual traditions. Some petrographs include astronomical marks, trails, and other mapping details. In Canada, some of the earliest Indigenous petroglyphs and petrographs can be found in Saskatchewan in areas near Saskatoon and Swift Current as well as Lac La Ronge Provincial park. To learn more about these ancient rock carvings and paintings please open the links here and here.

Time eroding pictograph heritage of the Churchill River.

Jones, T. (1974). Aboriginal Rock Paintings of the Churchill River. University of Saskatchewan.

The rock painting (above image) is believed to be created by the Anishinaabe people and is between 150-400 years old. The giant serpent called the “mishibijiw” (underwater panther or “The great lynx”). To read Anishinaabe folktales and legends please open the link here.

The Underwater Panther (“Mishibijiw” in Anishinaabe) (Adapted from Wikipedia)

The underwater panther or “great lynx” or “water lynx” is an important mythical water being in the mythology of the Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woods and Great Lakes, particularly among the Anishinabe, Algonquin, the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi First Nations. In various myths, the water lynx was thought to be the most powerful underwater creature. The great lynx is described as having the head and paws of a giant cat but it is covered in reptilian scales and spikes that along its back and tail, similar in appearance to dragons. To read more about this fascinating and powerful water being please open the link here. The water lynx is featured in some of the Nanabozho creation legends as well as the Innu who have Mishibizhiw stories. (Adapted from Wikipedia).

Two different styles of art: Mimetic and Expressive

We can learn to build upon the unique qualities of art from varied cultures and in the process develop a greater understanding of cultural, psychological, spiritual, philosophical, and ethical traditions from a global perspective. Often, artistic mediums were an intermediary and art objects were viewed as a means of communication with the ancestral and spirit world. The ideas presented in Anderson’s (1989) book can provide teachers with an important foundation for exploring ethnographic origins of art from many cultures. Essential intersections between art, religion, and culture are reflected in works of art and design. For example, Anderson writes that a close look at Inuit art, myth, and folklore can reveal deeper insights about the function of art in relation to the everyday life of the Inuit; important insights into the values, beliefs, and ideals of diverse cultures can be found in art. For the Inuit, art is seen to cross the border regions between the natural, human, and superhuman realms (Anderson, 1989, p. 81). Anderson writes that:

Eskimos recognize the frightening chasms that separate humans from, on the one hand, the cold, unresponsive material world that surround us and the spirit world where these beings could be either benign or dangerous and where some of these spirits could be subject to human control while others are beyond the realm of human affairs (p.47).

Materials like soap stone and bone are transformed into life forms (human, animal, environment). Art had a transformative and shamanic power to influence future events; good health, fertility, food, clothing, and shelter were dependent on the good spirits overpowering the evil spirits. Artistic detail and design motifs feature prominently in day-to-day clothing, children’s toys, weapons, drums, and sculpture. “Art enhanced Inuit life by giving pleasure to the creator and by adding sensuous beauty to the visual environment” (p.45). Beautiful sculptures and designed enhanced life in harsh environments. Art reflected a complex system of thought where earthly and spiritual realms of nature co-existed. Inuit art and aesthetics reveal a “system of thought in which art, is believed to enhance a person’s life today, improve one’s prospects for tomorrow, and accomplish this unique capacity to transform reality” (Anderson, p. 47). Anderson writes:

But Inuit myth, folklore, and art usage convey deeper ideas regarding art’s role in the world. The Inuit world view implicitly distinguishes among three realms of existence—the supernatural world, with its out-of the ordinary and awe-inspiring qualities, the social world of day-to-day human interaction, and the natural world of animals, plants, and inanimate objects. Many peoples tacitly accept the existence of these three worlds but ignore the problem of how they are related to each other. How can cold, lifeless elements become warm, living human flesh, and how can the spirit that lives within the flesh transcend its mortal habitation and touch the divine? There is considerable evidence that Eskimos conceptualize art as a sort of cultural “philosopher’s stone” that makes such transformation possible (Anderson, 1989, p. 49).

Anderson (1989) notes that art for the Inuit was recreational as well and served to relieve boredom during the coldest and longest days of confinement during the polar winters. Art was also inspirational and aspirational; it improved the likelihood that future life would be better—safer, healthier, and more prosperous (p. 47). Art along with ritual is a means by which morals may can touch the world of mystery and the “dreamtime” (p. 55).

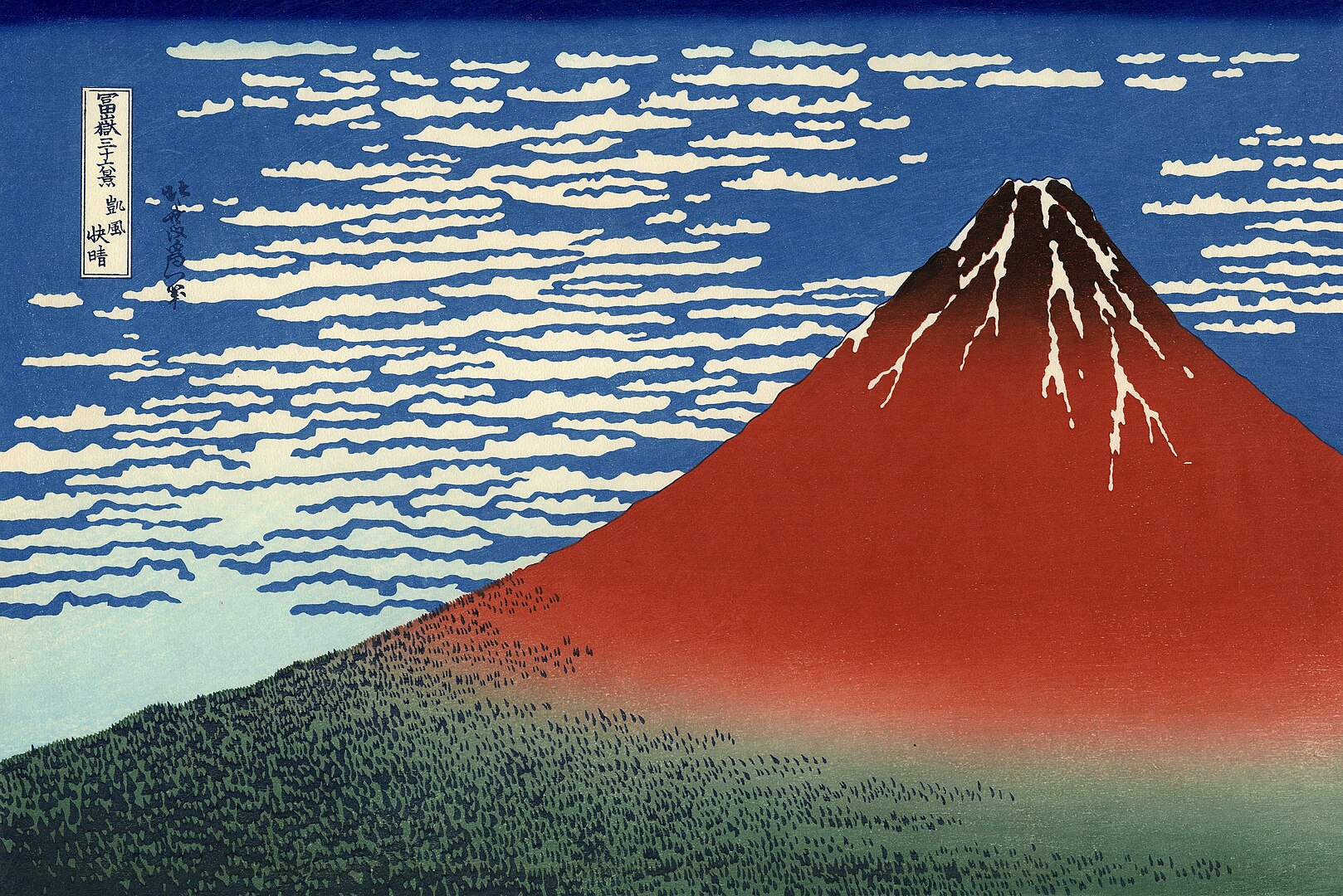

In Indigenous Australian cultures, the trees, lakes, and other natural phenomena can metamorphosize into spiritual mediators. Spirits reside in art objects (e.g. bark paintings, decorative bowls, animal sculptures) that are painted and decorated. “Where art is not an actual manifestation of the supernatural, it may provide the prime means whereby mortals can come into contact with the sacred”(Anderson, p. 248). Japanese paintings often feature powerful landscapes. The ancient Japanese religion of Shintoism viewed the natural environment as animated with spirit that are invisible to the human eye. In the Shinto creation myth, the Sun goddess was lured out of the cave of the heavens by the arts-music, dance, and the perfect mirror (Anderson, p. 241). These spirits can influence the visible universe and in order to abate negative spirits and promote positive spirts, shrines and temples were built in the sea or close to mountains and springs.

The Shinto belief that dynamic ever-changing spirits reside in nature, led to an aesthetic principle that is cross-culturally uncommon. According to Shintoism, some natural phenomena, such as mountains and streams, are the residents of animistic spirits that differ from human spirits only in being far stronger than any moral. If art is to portray the truly significant, then it must be a faithful representation of nature (Anderson, 1989, p. 177).

Additional Resources

- To read R.H. Blyth’s (1949/1981) Haiku: Eastern Culture please open the link here.

Additional Resources

“She is Transforming:”

Inuit Artworks Reflect a Cultural Response to Arctic Sea Ice and Climate Change ARCTIC

VOL. 73, NO. 1 (MARCH 2020) P. 67 – 80

https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic69945

Kaitlyn J. Rathwell

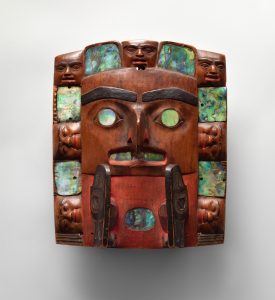

Art from the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada: Haida and Tsimshian Art

Unknown Artist, Tsimshian, Avian Headdress Frontlet, 1820-30. Wood, Abalone Shells, Pigment, and Nails. Pacific Northwest Coast, British Columbia, Canada. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Public Domain/Open Access https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/717587

Metropolitan Museum of Art Note about the Carving (Above):

“During certain ceremonies, Tsimshian leaders wear symbols that validate their authority, such as dance blankets woven from cedar bark fibers and mountain sheep wool or rattles carved in the shape of a raven. Among the most important elements of chiefly attire is the headdress. This avian example of a headdress centerpiece, or frontlet, was once adorned with goose down, a train of ermine skins, and a crown of spiky sea mammal whiskers. Its central image depicts a mythological bird-human. The strong beak, projecting wings, and realistic talons showcase the artist’s skill and recall similar three-dimensional imagery on monumental carvings.” (Metropolitan Museum of Art Note).

The avian/raven headdress carving (above) may be a manifestation of ancestral stories and legends about the raven, a central figure in Tsimshian (Pacific Northwest Coast Indigenous people) mythology. In a number of Indigenous mythologies, the raven is viewed as the creator of the universe and as an intermediary between its physical and spiritual realms. The following is an excerpt from the Raven Creation stories of the Tsimshian. The raven was also known as “Txamsem” or “giant.” To read more about the Tsimshian (Ts’msyen) culture please open the link here.

Raven Creation Story (Tsimshian)

“ The Tsimshian creation myth presupposes a dark and still universe populated by a variety of animal spirits. An animal chief pampers his son, causing him to fall sick and die, and his intestines are burned. The next day a new youth appears in the bed, healthy and visible in the darkness, “bright as fire.” The boy is adopted by the chief. Initially, this boy does not eat, but slave spirits trick him into eating scabs. This triggers an enormous appetite in the boy, who begins to eat so much that the chief and villagers send him away with a raven blanket. The boy leaves, and becomes Raven.

As Raven arrives in the mainland, he is insatiably hungry, causing great disruptions to those he meets. At various points of the myth he serves as a trickster.For example, after creating a slave from rotted wood, he disguises himself as a king and arrives in a village. The villagers tell the slave to invite Raven for dinner, but the slave says Raven is not hungry, and takes the food for himself. Raven builds a bridge from cabbage and as the slave crosses, he falls to his death. Raven descends into the valley to eat the food from the dead slave’s belly.

As Raven begins to develop a sense of generosity, he hosts a potlatch, in which he shares food with many guests. As he speaks, he wishes they would all turn to stone, and they do, giving form to a previously immaterial world.” (Tsimshian Raven Creation Story, Wikipedia).

African Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York highlights African Art as reflecting the “cradle of civilization;” they emphasizes that the “abrupt and violent manner in which most royal art forms of the kingdom of Benin were removed from their original context by the British in 1897, there is a dearth of documentation to situate individual works historically.” Please refer to the Metropolitan Museum of Art Essay on African Art here.

Art historians then proposed theories that connected the style of a particular work from Africa with their possible chronological time line. Dating back to 14th century Benin, the commemorative brass heads were commissioned by the kinds to honour their predecessor. Students can explore the historical origins of African art and its influences on Modern Art, for example.

“At its origins, the centralized city-state of Benin was founded by Edo-speaking peoples. The accounts by official court historians and descriptions provided by visitors evoke a vibrant cultural center continually redefined by its leadership through shifting internal and external power dynamics. According to oral tradition, circa 1300, Edo chiefs are reputed to have reached out to the leader of neighboring Ife, Oranmiyan, to establish a new divinely sanctioned royal dynasty. Since then, the investiture of Benin’s rulers to the title of obas has conferred upon them at once a role of chief priest officiating in important religious ceremonies and presiding over an elaborate structure of palace officials. During the fifteenth century reign of Oba Ewuare, Benin’s armies were formed and the fortification of its capital with a massive wall undertaken. In parallel, delegations of Portuguese traders assiduously sought to secure exclusive commercial treaties with this leader of the region’s most powerful polity. At its height in 1500, Benin’s authority extended to the Niger delta in the east and to the coastal lagoon of Lagos in the west. Its major exports of pepper, textiles, and ivory were exchanged for copious quantities of imported metals. This access to an influx of brass led to an explosion of creativity by court artists who transformed it into works for the palace ranging from ancestral portraits, positioned on royal altars, to decorative plaques depicting the oba, his courtiers, and foreign interlocutors. From the earliest such exchanges, those Europeans commissioned exquisite ivory artifacts from Edo carvers for princely collections back home.”

Lesson Plan Ideas

Ekphrasis: Paintings Inspired by Poetry and Verse

Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821-1872) was one of the greatest 19th Century landscape painters. Of African America and European descent, Duncanson’s powerful and beautiful painting draws upon Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Lotus Eaters” based upon Homer’s Book 9 of The Odyssey. In Book 9 “The Land of the Lotus Eaters,” Ulysses and his crew meet a peaceful but melancholy people who seem to be in a state of bliss. They give Ulysses’ men the mysterious lotus plant; soon after, the men are in a blissful state and have no desire to return home. Seemingly addicted to the enchanted lotus plant, the men quickly forget about their families and homeland; with great difficult, Ulysses is finally able to get his men back onto the ship. It could be that the idyllic setting that Duncanson created would symbolize a better life once slavery was abolished or there may been different hidden symbols that different viewers understand from the painting. Adam Lauder (2020) writes that Robert S. Duncanson lived for two years in Canada, and was greeted as an “honorary Canadian citizen” (Lauder, 2020, p. 2) when in arrived in Montreal in 1883. Lauder emphasizes that Duncanson had a major impact on the style and imagery of the Group of Seven painters in Canada.

Possibility and Place: Abolitionist Imaginary in the Landscape Paintings of Robert S. Duncanson

Adam Lauder (2020) writes:

“Land of the Lotus Eaters (1861) is a powerful precursor to contemporary Black liberatory aesthetics. While conceived by its African American creator as a “great picture” to rival the Old Masters, Robert S. Duncanson’s lush landscape is no static utopia outside history. The painter has transformed a familiar scene from the Western literary canon into a speculative encounter between civilizations, a comment on the racial politics of his day. Today, there is an urgent need to recover Duncanson’s visionary canvas as a catalyst for Canada’s storied tradition of landscape painting, a tradition more often associated with fraught notions of whiteness. Unlike the “purified” landscapes of Lawren Harris, for instance, which stake a nationalist claim on the North, Duncanson’s Land of the Lotus Eaters doesn’t erase the signs of African and Indigenous presence—though its message would have been legible only to those able to decipher them.”

“The digressive storytelling of Land of the Lotus Eaters could also be interpreted in autobiographical terms, as an allusion to Duncanson’s own forthcoming odyssey of wartime self-exile. When first exhibited in the artist’s hometown of Cincinnati, the painting was accompanied by a statement boldly announcing a forthcoming world tour that would take it, and its fearless creator, first to Canada, with later stops in the British Isles—this amid the perils of a civil war then only recently begun. Displayed in Toronto in November 1861, Land of the Lotus Eaters must have received an enthusiastic response, since Duncanson mounted a second showing there in 1861.”

Excerpt from Alfred Lord Tennyson‘s “The Lotos Eaters”

The charmed sunset linger’d low adown

Additional Resources

- To read the full text of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “The Lotos Eaters” please open the Lauder Canadian Art link here: Canadian Art)

- For more information about Robert S. Duncanson please open the link here

Key Takeaways

- Transcultural art connections encourage dialogue about art from global, interdisciplinary and multicultural perspectives.

- A global view of art can challenge viewers to re-vision and look at the world in new ways.

- One way of telling stories is through art.

- Many stories in art come from world religions; in addition, oral storytelling, myths, legends, and folklore from many cultures inspire art.

- Artists, worldwide, reframe ideas and experiences in order to generate new experiences.

- Explore “big ideas” (e.g. self, identity, the natural world, place, family, society, etc.) found in contemporary art to art of the past and from art in other cultures.

- Help students build a broader social, historical, and cultural understanding of visual art that encourages transformative learning and perspectives taking.

- Connect global art to individual experience is key to creating relevance and empathy.

- Explore the concept of “otherness” in art though propaganda, cultural ideology, and stereotypes.

- Explore a “sense of place” from different artistic styles and historical time periods;

- Enrich learners’ understanding about cultural differences in terms of the physical and spiritual views of the self in related to society and the natural world.

- Symbolism, meaning and style are central to understanding art across cultures.

- Provide varied examples of artistic styles across cultures and help students apply their understandings and insights in authentic ways.

Additional Resources

- Metropolitan Museum of Art: Teaching Resources for the Classroom.

- Art = Discovering infinite connection in art history from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Phaedon, 2020.

- Letts, M.J. (2015).Cross-cultural issues in art: Frames for understanding, Vol. 56(2), 187-190. National Art Education Association.Roland, C. (2023). “Big Ideas about Art.”

- Tate Britain. Art Activities in the Classroom: Teaching Resources.

- Young, C. (2015). Art at the intersection of cultures. Metropolitan Museum of Art.