11.3 Solitude, Loneliness, and Identity

Psychologically compelling short stories like “The Bet” by Anton Chekhov, “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by Leo Tolstoy, and “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” by Ernest Hemingway focus on existential themes that recur in life. While the authors do not offer neat solutions, the dilemmas that their characters face challenge readers to think about the values that guide their decisions and life choices. Does my life matter and will I make a positive difference in the world? Do we need each other to find fulfillment? What causes people to experience loneliness and despair? To what extent can solitude be beneficial? Ultimately, are we all on our own when a catastrophic event disorients our life? What makes life worth celebrating? How do we find a sense of purpose and meaning in life? How do we forge meaningful relationships when one’s sense of trust has been betrayed? How can loneliness lead to depression and despair? Are we living in (to quote W.H. Auden) “the age of anxiety?”

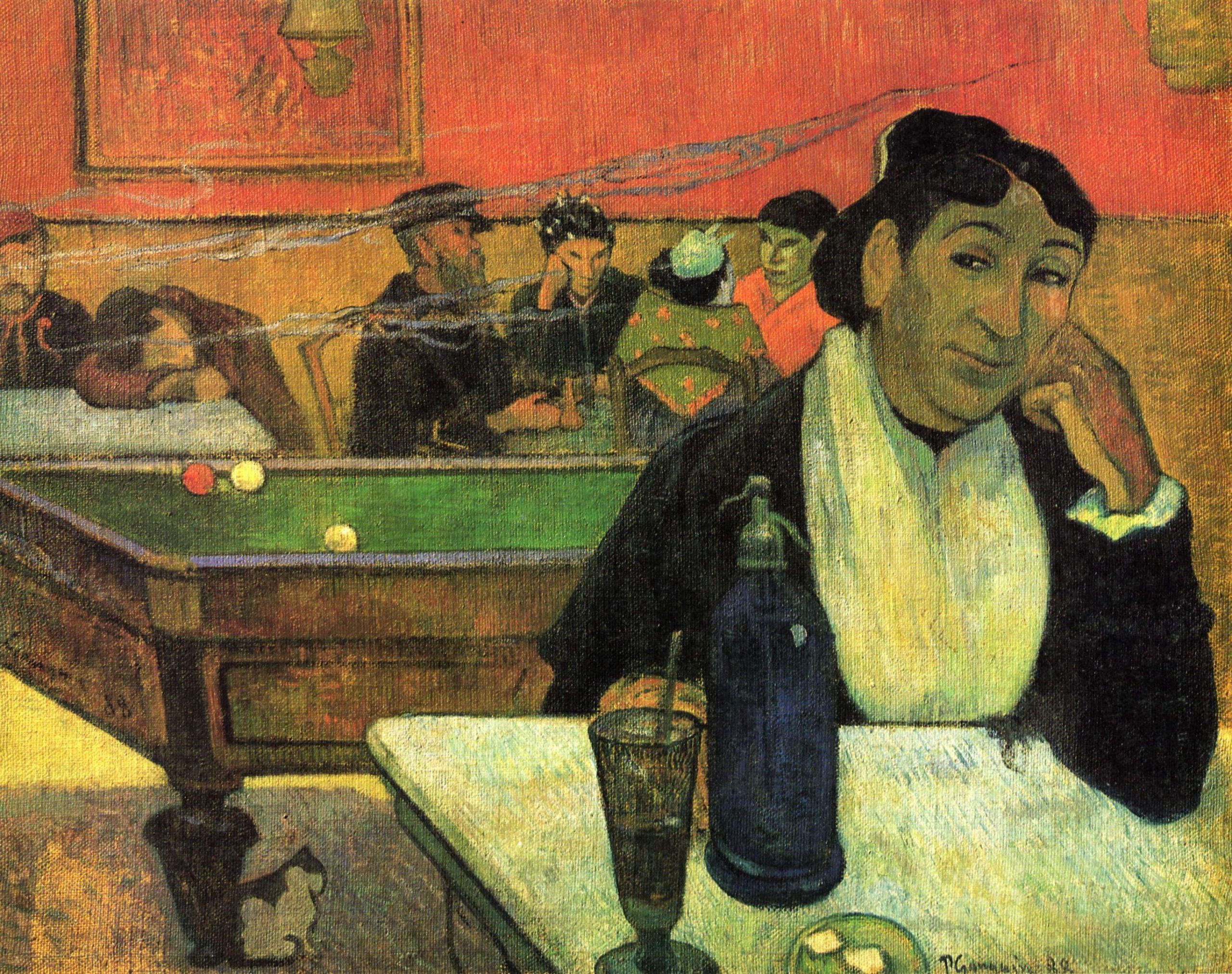

Artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin convey the themes of loneliness and alienation in their art. For van Gogh, the experience of solitude and loneliness were hard to shake. Successful relationships with women seemed to elude him; he found solace and inspiration in nature and in his art. In hundreds of letters to his beloved brother Theo, van Gogh expresses his emotional turmoil with the vivid intensity found in his brilliant landscapes, portraits, and still life. Paul Gaugin sought an escape from the stresses of Parisian society in Tahiti. For Gaugin, the pristine exotic beauty of the South Seas could not prevent him from spiralling into despair and financial insecurities. One of his great paintings, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? challenges the viewer to think more deeply about the meaning of life.

Courtesy: By Paul Gauguin – Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36264337

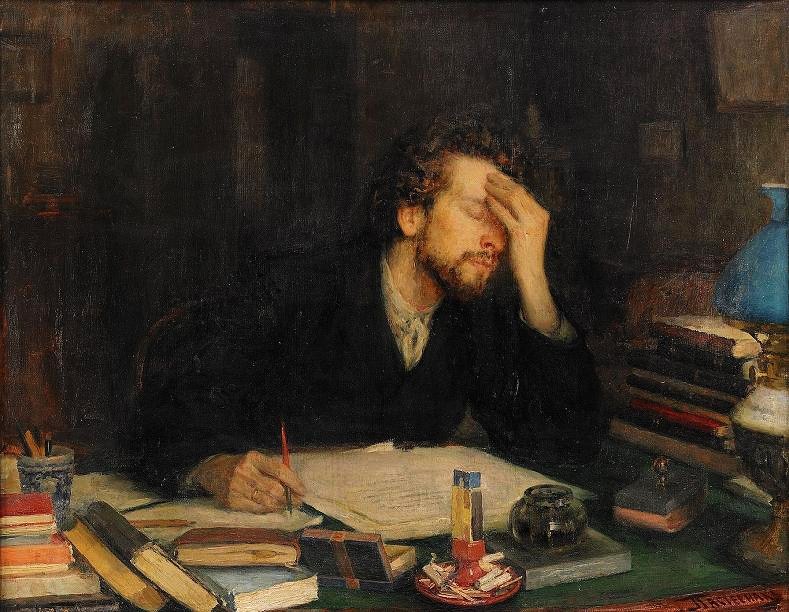

Anton Chekhov’s famous short story “The Bet” (1889) centres around themes of values, choices, spiritual enlightenment, greed, materialism vs intellectual and spiritual pursuits, and identity. Arguing the merits of life imprisonment against capital punishment, a young lawyer agrees to be kept a “prisoner” for fifteen years to prove that life imprisonment is better than no life at all. The banker and lawyer wager a bet for 2 million dollar that would be paid to the lawyer if he lived in isolation for fifteen years. His “jailor” is a materialistic banker intent on never paying the bet. The lawyer’s isolation transforms him and he achieves a sense of spiritual enlightenment; in isolation, the lawyer begins to reassess his values. Through reading and a vicarious engagement with philosophy, religion, and literature, the lawyer adopts a profoundly negative view of human nature, seeing individuals as hypocritical, shallow, and destructive.

Courtesy: By Ilya Repin – [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2009792

Excerpt from “The Bet” (1889) by Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)

In the second half of the sixth year, the prisoner began zealously to study languages, philosophy, and history. He fell on these subjects so hungrily that the banker hardly had time to get books enough for him. In the space of four years about six hundred volumes were bought at his request. It was while that passion lasted that the banker received the following letter from the prisoner: “My dear goaler, I am writing these lines in six languages. Show them to experts. Let them read them. If they do not find one single mistake, I beg you to give orders to have a gun fired off in the garden. By the noise I shall know that my efforts have not been in vain. The geniuses of all ages and countries speak in different languages; but in them all burns the same flame. Oh, if you knew my heavenly happiness now that I can understand them!” The prisoner’s desire was fulfilled. Two shots were fired in the garden by the banker’s order.

Later on, after the tenth year, the lawyer sat immovable before his table and read only the New Testament. The banker found it strange that a man who in four years had mastered six hundred erudite volumes, should have spent nearly a year in reading one book, easy to understand and by no means thick. The New Testament was then replaced by the history of religions and theology.

During the last two years of his confinement the prisoner read an extraordinary amount, quite haphazard. Now he would apply himself to the natural sciences, then would read Byron or Shakespeare. Notes used to come from him in which he asked to be sent at the same time a book on chemistry, a text-book of medicine, a novel, and some treatise on philosophy or theology. He read as though he were swimming in the sea among the broken pieces of wreckage, and in his desire to save his life was eagerly grasping one piece after another.

(Please open the link here to read the complete story of “The Bet” by Anton Chekhov).

Values, Relationships, and a Life in Review

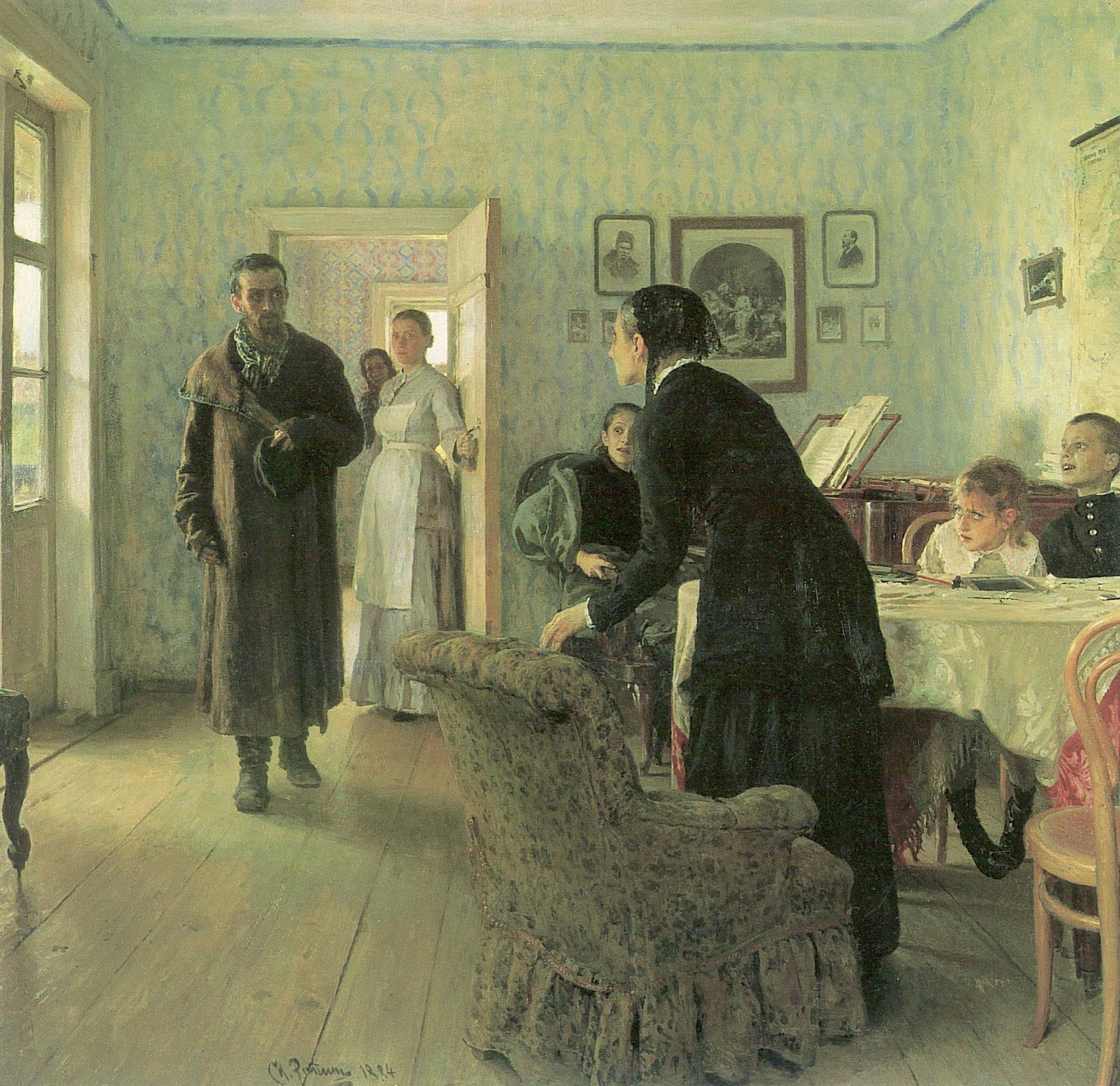

Leo Tolstoy’s novella “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” (1886) is considered a literary masterpiece of psychological realism. Tolstoy’s novella is a critique of material values, social conformity, and a society where spiritual faith, awareness, and compassion have been eroded. It is the story of a 19th century high court Russian judge who through ambition and professional connections created a seemingly successful life for himself and his family. Suffering from a terminal illness at the age of forty-four, Ivan Ilyich begins to take stock of his life. With melancholy and regret, Ivan reflects on a loveless marriage and his commitment to professional duties. The “centre of gravity” quickly transferred from his marriage and home life to his official work” and “very soon within a year of his wedding, Ivan Ilyich had realized that marriage, is a very intricate and difficult affair” (p.182) and that an external show of unity would be “required by public opinion.” Ivan compartmentalized his life to avoid stress and anxiety. In the first part of the story, Ivan’s professional associates reflect on his death and think of possible promotions, transfers, and opportunities that his job vacancy would create. Illich’s demise paves the way for their own ambitions in the second and much longer part of the novella, Tolstoy presents a retrospective panorama where Ivan Illich reviews events from his life, his professional duties, “the arrangement of his life” (p.224), and the decisions and choices he seems to regret. Ilyich reflects back on his youth and middle age and wonders if “he had not spent his life as he should have done” (p.226) He comes to the conclusion that much of his life has been a “lie” and that no one has truly cared or loved him. The physical suffering he experiences mirrors his inner turmoil and psychic pain. Is it too late for redemption and spiritual enlightenment? Like Chekhov, Tolstoy weaves a tapestry of human emotion in his stories; the deep anguish and desperation contrasts with moments of joy and relief. Characters experience the depths of despair that contrast with a sense of optimism, reconciliation, redemption, and possible transformation. Tolstoy’s existential novella could be compared to contemporary works such as “Tuesdays with Morrie” by Mitch Albom, Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” and “The Road” by Cormac McCarthy.

Excerpt from “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by Leo Tolstoy (1883):

“It occurred to him that what had appeared perfectly impossible before, namely that he had not spent his life as he should have done, might after all be true. It occurred to him that his scarcely perceptible attempts to struggle against what was considered good by the most highly placed people, those scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and the rest all false. And his professional duties, and the whole arrangement of his life and of his family, ad all his social and official interests, might have all been false. He tried to defend all those things to himself and suddenly felt the weakness of what he was defending. There was nothing to defend.

‘But if that is so,’ he said to himself, ‘and I am leaving this life with the consciousness that I have lost all that was given me and it is impossible to rectify it —what then?’ He lay on his back and began to pass his life in review in quite a new way. In the morning when he saw first his footman, then his wife, then his daughter, and then the doctor, their every word and movement confirmed to him the awful truth that had been revealed to him during the night. In them he saw himself—all that for which he had lived—and saw clearly that it was not real at all, but a terrible and huge deception which had hidden both life and death. This consciousness intensified his physical suffering tenfold. He groaned and tossed about, and pulled at his clothing which choked an stifled him. And he hated them on that account.

He was given a large dose of opium and became unconscious, but at noon his sufferings began again […] (Tolstoy, 1883).

From: Tolstoy, L. (2020).Tolstoy Selected Stories. Arcturus Publishing (p.224).

Art Connections

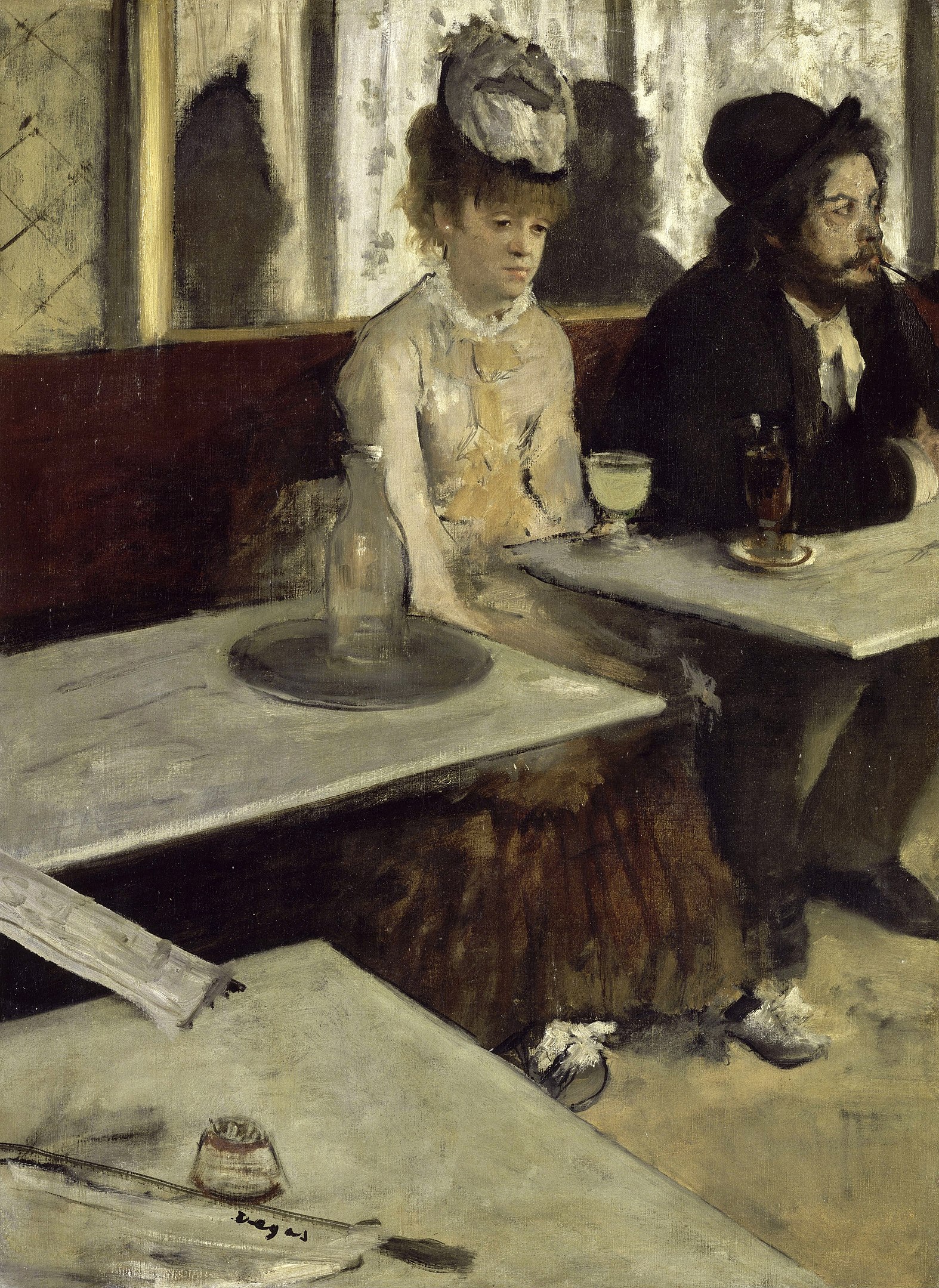

considering these famous depictions of night cafés, which image best reflects the overall tone of the following Hemingway story? What mood or tone is conveyed in the paintings by van Gogh? Compare this painting with Degas’ café. What message are these paintings sending about life? How are the people in the paintings presented? How would you describe their emotional states? To what extent do the colours in the paintings reflect varied emotions?

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 1. The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.2. Unknown source3. Yale University Art Gallery, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=151915

Additional Resources

Courtesy: By Paul Gauguin – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=151335

Courtesy: By Edgar Degas – Google Art Project: Home – pic Maximum resolution., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20303082

Loneliness, Connection, and Life Values

“A Clean Well-Lighted Place” by Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) written in 1933 is an existential commentary about life, loss, and the need for connection and communication. The two waiters, one young, and one older, have different attitudes toward an older man who frequents the café. His wife recently died, he suffers from melancholy depression, and he had attempted suicide. While the younger waiter is impatient and wishes to close the café and go home to his wife, the older waiter has compassion, empathy, and insight, insisting that the patron needs a place to go and that the “clean and well-lighted” café is a safe haven for the man. The café provides an atmosphere of solace and comfort. Hemingway’s characters represent different spectrums of human experience—one which is more self-centered and pragmatic while the other more compassionate and sensitive. The older waiter has lingering questions and thoughts about the meaning of life:

“We are of two different kinds,” the older waiter said. He was now dressed to go home. “It is not a question of youth and confidence although these things are very beautiful. Each night I am reluctant to close up because there may be someone who needs a café.”

“Hombre, there are bodegas open all night long.”

“You do not understand. This is a clean and pleasant café. It is well lighted. The light is very good and also, now, there are shadows of the leaves.”

“Good night,” said the younger waiter.

“Good night,” the other said. Turning off the electric light, he continued the conversation with himself.

It is the light of course but it is necessary that the place be clean and pleasant. You do not want music. Certainly you do not want music. Nor can you stand before a bar with dignity although that is all that is provided for these hours. What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanliness and order….” (p.1018).

From: “A Clean Well- Lighted Place” by Ernest Hemingway in Stott, J.C., Jones, R.E., & Bowers, R. (Eds.) (1998). The Harcourt anthology of literature (2nd edition). Harcourt Canada. (pp.1015-1018)

For the complete short story of “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” please open the link here.

Courtesy: By Frederic Leighton – http://www.maryhillmuseum.org/Press/Images_for_Publication/Images/Permanent_Collection/Lord_Leighton_Solitude.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1669553

Courtesy: By Constance Marie Charpentier – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7755475

Related Essays and Art on Loneliness and Alienation

Burns, H. (2022). “You Can Learn to Love Being Alone.”Please open the link here.

Garfunkel, A., & Simon, P. (1965), Lyrics “I am a rock, I am an island. “

McCartney, P. (1966). “Eleanor Rigby.”

Leung, W. (2017). Globe and Mail. Review of Solitude (Michael Harris, 2017) makes the case for being alone. Please open the link here.

Poems about loneliness and isolation. Please open the link here

and here.

Storr, A. (1989 Solitude: A Return to the Self. Ballentine Books.

Ten Books on Loneliness (The Guardian, UK). Please open the link here.

The paintings of Edward Hopper (1882-1967) often feature dramatic scenes of individuals who seem lonely and disconnected from others. You can explore the work of Edward Hopper by clicking on the links below.

“The Nighthawks” by Edward Hopper (1942)

Automat by Edward Hopper (1927).

Additional Information:Paintings to Show that Solitude Might be your Best Companion

Questions for Further Inquiry

Images of Solitude: What can be gained from solitude, meditation, and a communication with nature? Why have many people become alienated from nature and reflective contemplation?

Richard Wilson (1714-1782). Solitude (c. 1762-1770). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States.

Courtesy: Paul Mellon Collection. “https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.61395.html” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Henry David Thoreau found a sense of “liberty” in Nature. Rather than fearing loneliness and isolation, Thoreau saw nature as a companion and source of comfort.

An Excerpt from Solitude by Henry David Thoreau

“Some of my pleasantest hours were during the long rain storms in the spring or fall, which confined me to the house for the afternoon as well as the forenoon, soothed by their ceaseless roar and pelting; when an early twilight ushered in a long evening in which many thoughts had time to take root and unfold themselves. In those driving north-east rains which tried the village houses so, when the maids stood ready with mop and pail in front entries to keep the deluge out, I sat behind my door in my little house, which was all entry, and thoroughly enjoyed its protection. In one heavy thunder shower the lightning struck a large pitch pine across the pond, making a very conspicuous and perfectly regular spiral groove from top to bottom, an inch or more deep, and four or five inches wide, as you would groove a walking-stick. I passed it again the other day, and was struck with awe on looking up and beholding that mark, now more distinct than ever, where a terrific and resistless bolt came down out of the harmless sky eight years ago. Men frequently say to me, “I should think you would feel lonesome down there, and want to be nearer to folks, rainy and snowy days and nights especially.” I am tempted to reply to such,—This whole earth which we inhabit is but a point in space. How far apart, think you, dwell the two most distant inhabitants of yonder star, the breadth of whose disk cannot be appreciated by our instruments? Why should I feel lonely? is not our planet in the Milky Way? This which you put seems to me not to be the most important question. What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? I have found that no exertion of the legs can bring two minds much nearer to one another. What do we want most to dwell near to? Not to many men surely, the depot, the post-office, the bar-room, the meeting-house, the school-house, the grocery, Beacon Hill, or the Five Points, where men most congregate, but to the perennial source of our life, whence in all our experience we have found that to issue; as the willow stands near the water and sends out its roots in that direction. (Walden or A Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau).

Exercises

Courtesy: By Giovanni Bellini – egGQB5gOZujX4g — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=464748