Chapter 10: Painting Shakespeare: Selected Art Images, Dramatic Excerpts, and Related Verses

The plays of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) form a panoramic landscape of human emotion. From history, comedy, tragedy, and romance to “problem plays such as The Tempest and Twelfth Night that defy neat categorization, Shakespeare’s plays convey psychological depth, human motivation, and conflict. Themes connected to pain, loss, revenge, forgiveness, and redemption are interwoven with compelling characters and intriguing plots. Earlier A.L. Rowse (1978) wrote that “our very insecurity, the sense of contingency upon which all life hangs, the clouds hanging over humanity in our time, the nuclear threat to life on the planet, give us better—or, rather, worse—reason for understanding the tragic depiction of life in Shakespeare’s greatest works” (p.7). These insights are very applicable to 2024 and beyond. As a world, we face climate change, planetary sustainability, pandemics, ongoing conflict and war, and the brutality that infiltrates life on a daily basis. Shakespeare’s romances and comedies also provide joy and inspiration as we are transported to fantastical realms. Throughout the centuries, the plays of Shakespeare have been beautifully illustrated and artistic depictions of characters and scenes can be studied by themselves or with selected quotations from the plays.

It is not the intention of this section to present a comprehensive analysis of Shakespeare’s plays and art images associated with them; rather, this section highlights selected paintings that are complemented with quotations from well-known plays. The connections between art and Shakespeare’s texts provide some ideas for teachers and students who may wish to explore Shakespeare in art more closely.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912). Antony and Cleopatra (1912). Public Domain. By Lawrence Alma-Tadema – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1170930

“In time we hate what we often fear.” (Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, 1.1.)

Note about the painting:

“This painting, by the Dutch-British artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), depicts an early encounter between two people who would become one of the ancient world’s most famous power couples. Reclining in her pleasure barge, wearing the sheer white clothing, is Queen Cleopatra of Egypt (r. 51 BCE-30 BCE). Behind her in the background is the prominent Roman general and triumvir, Mark Antony (c. 83-30 BCE), shown leaning over in his seat to check out the queen. Inspiration for this scene was likely drawn from a description by the biographer, Plutarch (c. 50-120), of an encounter between Antony and Cleopatra at the Cydnus (Berdan) River. He wrote:

“She came sailing up the river Cydnus, in a barge with gilded stern and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps. She herself lay all along under a canopy of cloth of gold, dressed as Venus in a painting, and beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood on each side to fan her. Her maids were dressed like sea nymphs and graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes. The perfumes diffused themselves from the vessel to the shore, which was covered with multitudes, part following the galley up the river on either bank, part running out of the city to see the sight. The market-place was quite emptied, and Antony at last was left alone sitting upon the tribunal” (Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, Life of Antony, chapter 26).” (The Historian’s Hut).

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), Tomb Scene from Romeo and Juliet, “Noise again! then I’ll be brief,” exhibited 1790 and 1791. Oil on canvas, Derby Museum and Art Gallery, City of Derby, Derbyshire, East Midlands, By Joseph Wright of Derby – http://www.abcgallery.com/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8265984.

Note about the Painting:

“Romeo and Juliet: the Tomb Scene is a painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, completed by 1790, exhibited in 1790 and 1791, shown in the Derby Exhibition of 1839 in the Mechanics’ Institute, and now displayed in Derby Museum and Art Gallery. The painting exhibits Wright’s famed skill with nocturnal and candlelit scenes. It depicts the moment in Shakespeare‘s Romeo and Juliet when Juliet, kneeling beside Romeo’s body, hears a footstep and draws a dagger to kill herself. The line is “Yea, noise? Then I’ll be brief. O happy dagger!””

Selected Plays and Paintings

This early tragedy centers around Richard of Gloucester, rapacious and ambitious in his quest to become king at any cost. Using deceit, treachery, and manipulation against anyone who opposes him, Richard orchestrates the murders of his brothers, nephews (“the princes in the tower”), and others who stand in his way. In recent years, the history of Richard the Third has been revisited from different historical and socio-political/cultural angles. How are themes such as power and corruption, hypocrisy, and “villainy” presented? How can truth be differentiated from fiction when we read about historical figures like Richard III? To what extent did his physical disability position him as a “villain”?

Additional Resources

“As Richard III opens, Richard is Duke of Gloucester and his brother, Edward IV, is king. Richard is eager to clear his way to the crown. He manipulates Edward into imprisoning their brother, Clarence, and then has Clarence murdered in the Tower. Meanwhile, Richard succeeds in marrying Lady Anne, even though he killed her father-in-law, Henry VI, and her husband.

When the ailing King Edward dies, Prince Edward, the older of his two young sons, is next in line for the throne. Richard houses the Prince and his younger brother in the Tower. Richard then stages events that yield him the crown.

After Richard’s coronation, he has the boys secretly killed. He also disposes of Anne, his wife, in order to court his niece, Elizabeth of York. Rebellious nobles rally to Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. When their armies meet, Richard is defeated and killed. Richmond becomes Henry VII. His marriage to Elizabeth of York ends the Wars of the Roses and starts the Tudor dynasty” (Folger Shakespeare Library, 2023).

Quotations Spoken by the Duke of Gloucester, King Richard III

“And thus I clothe my naked villainy

With odd ends stolen out of holy writ;

And see a saint, when most I play the devil.” (Shakespeare, 1564-1616. Richard III, 1.3.).

“Since I cannot prove a lover…I am determined to prove a villain” (Shakespeare, 1564-1616. Richard III, 1.1).

“The lights burn blue. It is now dead midnight

Cold fearful drops stand on my trembling flesh.

What I do fear? Myself? There’s none else by.” (Shakespeare, 1564-1616. RIchard III, 3. 5.)

“A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!” (Shakespeare, 1564-1616. Richard III, 5. 4.)

“Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York.” (Shakespeare, 1564-1616. Richard III. 1. 1.)

The Princes in the Tower by John Everett Millais

“So wise so young, they say, do never live long” (Shakespeare, 1564-1616. Richard III, 3.1. )

Note about the Painting The Two Princes in the Tower by John Everett Millais

John Everett Millais’ The Princes in the Tower refers to the apparent murder in England in the 1480s of the deposed King Edvard V of England Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York. These two brothers were the only sons of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, surviving at the time of their father’s death in 1483. When they were 12 and 9 years old, respectively, they were lodged in the Tower of London by their paternal uncle and all-powerful regent the Duke of Gloucester. This was supposedly in preparation for Edward V’s forthcoming coronanation. However, before the young king could be crowned, he and his brother were declared illegitimate. Gloucester ascended the throne as Richard II.

It is unclear what happened to the boys after the last recorded sighting of them in the tower. It is generally assumed that they were murdered; a common hypothesis is that they were killed by Richard in an attempt to secure his hold on the throne. Their deaths may have occurred sometime in 1483, but apart from their disappearance, the only evidence is circumstantial. As a result, several other hypotheses about their fates have been proposed, including the suggestion that they were murdered by their maternal Duke of Buckingham or future brother-in-law King Henry VII, among others….

In 1674, workmen at the tower dug up, from under the staircase, a wooden box containing two small human skeletons. The bones were widely accepted at the time as those of the princes, but this has not been proven and is far from certain. King Charles II had the bones buried in Westminster Abbey, where they remain.” (Wikipedia).

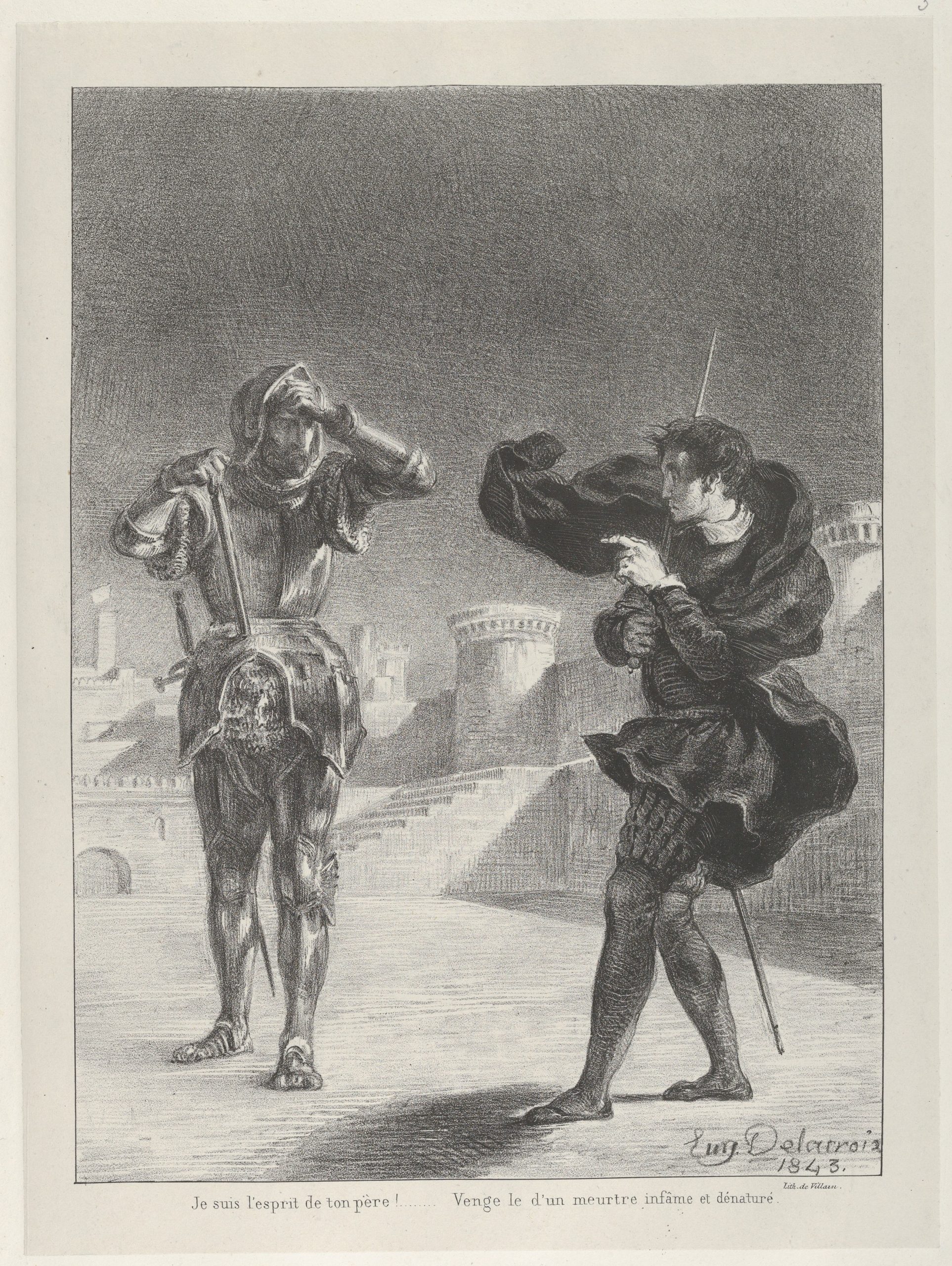

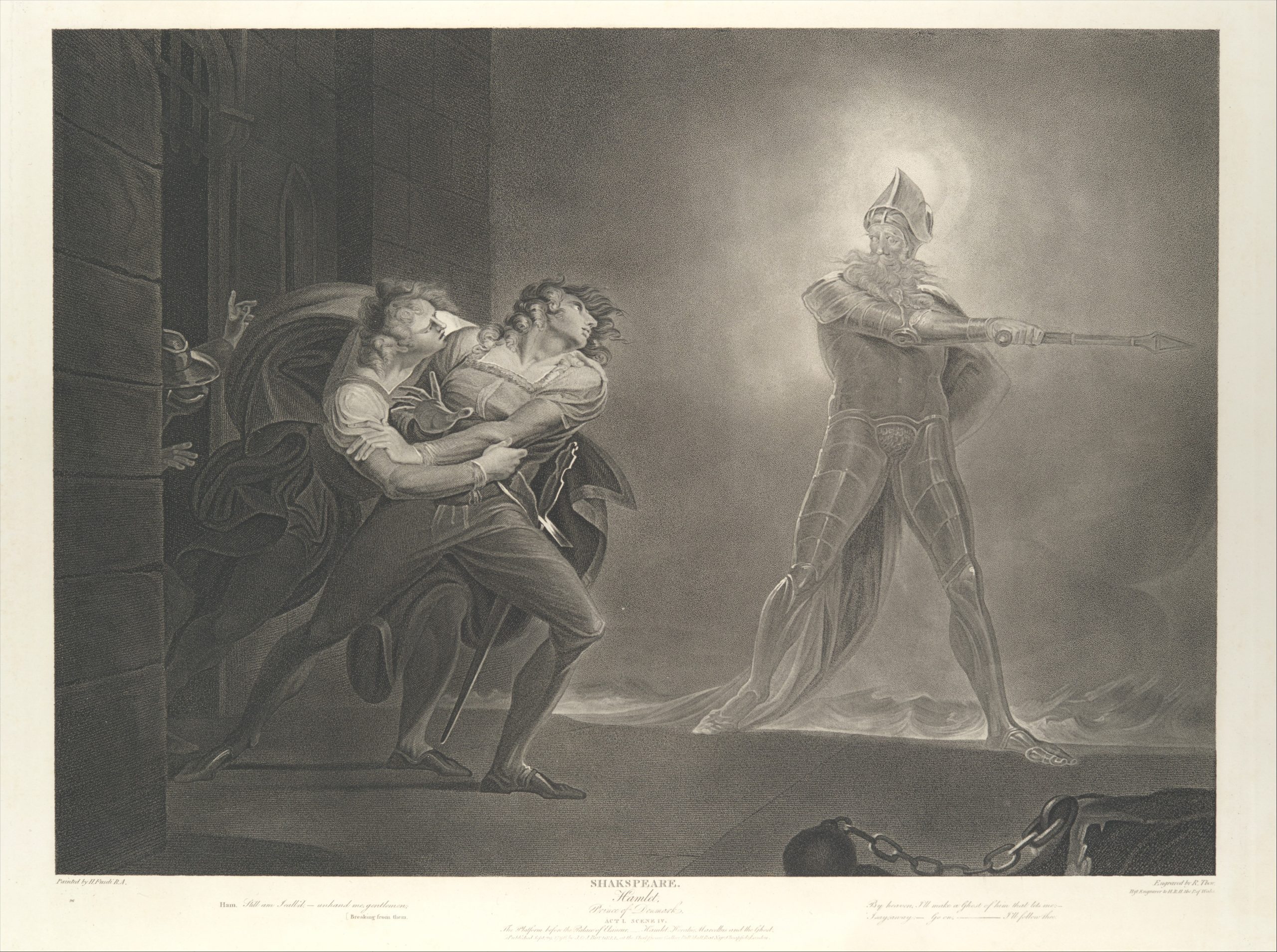

Selected Art and Verses from Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark is William Shakespeare’s most well-known and longest play (29,551 words). This tragedy describes the story of Prince Hamlet and his quest to seek revenge against his uncle Claudius who murdered his father, seized control of the crown, and married his mother Gertrude. With complex sub-plots and a panorama of memorable characters, Hamlet explores existential themes that address the meaning of life and whether or not our lives on earth make a difference. Free will, hypocrisy, friendship, vengeance, loyalty, and fate are explored as Hamlet seeks to avenge his father’s murder while those around him conspire against him. Love, madness, and elements of the supernatural create an atmosphere of suspense and foreboding. The play’s opening scene is set on the ramparts at Elsinore, the capital of Old Denmark. It is in the opening scene when the ghost of King Hamlet appears. Horatio, Hamlet’s friend, promises the guards Marcellus and Bernardo that he will report the appearance of the ghost to Hamlet. Artists such as Eugene Delacroix and Henri Fusseli recreate the suspense, emotion, and anguish in their paintings and etchings.

Lithographs of Hamlet

To view the masterworks of Eugene Delacroix please open the link here.

To view the complete Hamlet lithographs by Eugene Delacroix, please open the link here.

Metropolitan Museum Art Notes:

“Fascinated by the supernatural, Fuseli found rich subjects in Shakespeare. A life-long devotee, the artist read the plays as a youth in Zurich then devised an elaborate mural scheme devoted to admired plays while in Rome during the 1770s. After settling in London, Fuseli contributed paintings to John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, launched in 1786 as an exhibition cum print-publishing scheme funded by subscribers. Thew’s print reproduces Fuseli’s conception of the ghost scene at the start of “Hamlet” where the prince’s murdered father appears outside Elsinore Castle to demand vengeance. This impression comes from an American reissue of 1852 spearheaded by Shearjashub Spooner, a New York dental surgeon, writer and art scholar who acquired Boydell’s heavily worn plates and had them reworked. His New York edition was printed on thick cream paper with small numbers added in the lower left margin, this being number 96.” (Metropolitan Museum Art Notes)

For more information about Henry Fusseli and his fascination with the uncanny and supernatural please open the link here.

“Angels and Ministers of Grace Defend Us” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 1.1.)

Angels and ministers of grace defend us!

Be thou a spirit of health or goblin damn’d,

Bring with thee airs from heaven or blasts from hell,

Be thy intents wicked or charitable,

Thou com’st in such a questionable shape

That I will speak to thee. I’ll call thee Hamlet,

King, father, royal Dane. O, answer me?

Let me not burst in ignorance, but tell

Why thy canoniz’d bones, hearsed in death,

Have burst their cerements; why the sepulchre

Wherein we saw thee quietly inurn’d,

Hath op’d his ponderous and marble jaws

To cast thee up again. What may this mean

That thou, dead corse, again in complete steel,

Revisits thus the glimpses of the moon,

Making night hideous, and we fools of nature

So horridly to shake our disposition

With thoughts beyond the reaches of our soul? (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 1.5.)

Note about the Hamlet Lithographs by Eugene Delacroix

“In 1834 Eugene Delacroix began a series of lithographs devoted to Hamlet, creating moody images that mirror the troubled psyche of the prince. Choosing key scenes and poetic passages, the artist’s highly personal and dramatic images were unusual in France, where interest in Shakespeare developed only in the nineteenth century. Here, in act 1, scene 5, the prince has followed his father’s spirit to learn that he is: “”Doom’d for a certain term to walk the night, / And for the day confined to fast in fires,/ Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature/ Are burnt and purged away.” When the ghost reveals that he was murdered by Hamlet’s uncle and demands revenge, his son responds with hesitancy with shocked surprise. Gihaut frères published the artist’s thirteen-print set in 1843, with a second expanded edition of sixteen issued by Bertauts in 1864. Cooly received at first, the prints eventually were recognized as one of the artist’s most significant achievements.”(Wikimedia).

Well- known quotations spoken by Gertrude, Queen of Denmark

“Good Hamlet, cast thy knighted colour off,

And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark,

Do not for ever with thy vailed lids

Seek for thy noble father in the dust;

Thous know’st ‘tis common: all that lives must die,

Passing through nature to eternity.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 1.2.)

“The lady dost protest too much, methinks.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 3.2.)

“O Hamlet, speak no more;

Thou turn’st mine eyes into my very soul;

And there I see such black and grained spots

As will not leave their tinct….

O, speak to me no more;

These words, like daggers, enter in mine ears;

No more, Sweet Hamlet.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 3. 4.)

“This is the very coinage of your brain;

This bodiless creation ecstasy Is very cunning in.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 3. 4.)

“Sweets to the sweet: farewell!

I hoped thou shouldst have been my Hamlet’s wife;

I thought thy bride-bed to have deck’d, sweet maid,

And not have strew’d thy grave.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 5. 1.)

“I Have of Late Lost my Mirth”

“I will tell you why; so shall my anticipation prevent your discovery, and your secrecy to the King and Queen moult no feather. I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises; and indeed, it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why, it appears no other thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is man! How noble in reason? How infinite in faculties, in form and moving, how express and admirable? In action how like an angel? In apprehension, how like a god? The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals. And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me; no, nor woman neither, though by your smiling you seem to say so.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 2.2).

“To Be or Not to Be” (William Shakespeare)

“O heat, dry up my brains. Tears seven times salt” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 4. 6.).

O heat, dry up my brains. Tears seven times salt,

Burn out the sense and virtue of mine eye.

By heaven, thy madness shall be paid by weight,

Till our scale turn the beam. O rose of May!

Dear maid, kind sister, sweet Ophelia!

O heavens, is’t possible a young maid’s wits

Should be as mortal as an old man’s life?

Nature is fine in love, and where ’tis fine,

It sends some precious instance of itself

After the thing it loves. (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 4.6.)

“Alas, poor Yorick” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 5.1.).

“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio; a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy; he hath borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how abhorred in my imagination it is! My gorge rises at it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft. Where be your gibes now? Your gambols? Your songs? Your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table on a roar? (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 5.1).

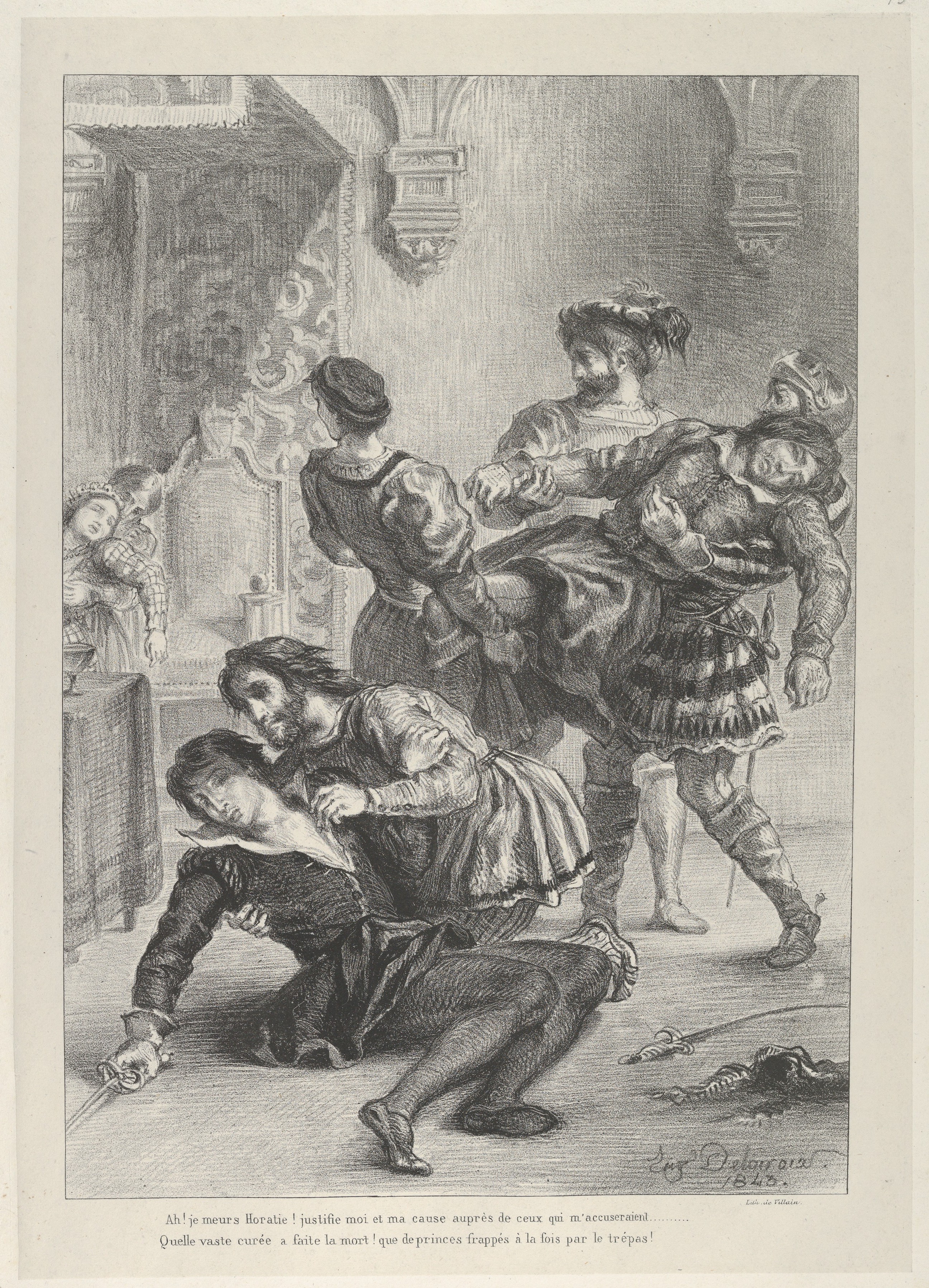

by Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863), The Death of Hamlet, 1843. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337111” by Metropolitan Museum of Art is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Museum Notes

“In the dramatic final composition of Delacroix’s “Hamlet” suite, based on act 5, scene 2, Laertes and Hamlet have killed each other in a duel and the queen has died from drinking poison intended for her son. (The king, who appears at this point in the play, is absent from Delacroix’s version.)” (Retrieved Feb. 18, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337111)

“Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince,

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest. “ (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 5.2.

Get Thee to a Nunnery (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 3.1.)

“Get thee to a nunnery. Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners? I am myself indifferent honest; but yet I could accuse me of such things that it were better my mother had not borne me. I am very proud, revengeful, ambitious, with more offences at my beck than I have thoughts to put them in, imagination to give them shape, or time to act them in. What should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven? We are arrant knaves all, believe none of us. Go thy ways to a nunnery. Where’s your father?” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 3.1)

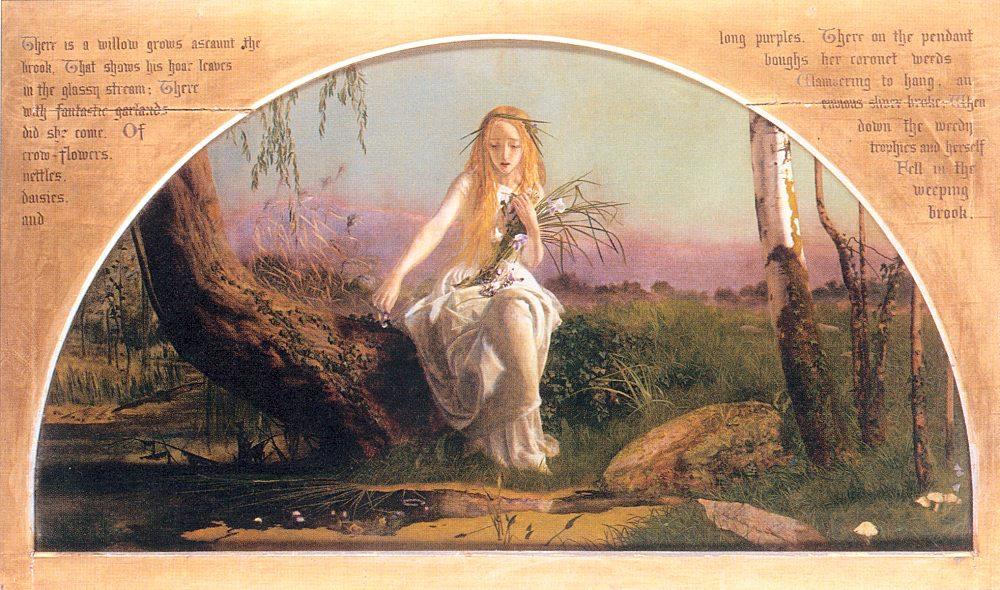

Pre-Raphaelite Images of Ophelia

William Waterhouse and John Millais created different versions of Ophelia; each artistic images reflects Ophelia’s inner anguish. Confused by abusive behavior and rejection, she begins a descent into madness and self-destruction. Gertrude’s tribute to Ophelia in Act V reflects the tragic circumstances of her death.

Well-known Lines Spoken by Ophelia

“They say the owl was a baker’s daughter. Lord, we know what we are, but know not what we may be. God be at your table.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 5. 5).

“Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s day,

All in the morning betime,

And I a maid at your window,

To be your Valentine.

Then up he rose, and donn’d his clothes,

And dupp’d the chamber-door;

Let in the maid, that out a maid

Never departed more.” (Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 4.5.)

“I hope all will well. We must be patient: but I cannot choose but weep, to think they should lay him ‘I the cold ground. My brother shall know of it: and so I thank you for your good counsel. Come, my coach! Good night, ladies: good night, sweet ladies; good night, good night”(Shakespeare, 1599-1601. Hamlet, 4.5.).

Notes on John Everett Millais’ painting of Ophelia, Tate Britain, London, UK.

“The scene depicted is from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act IV, Scene vii, in which Ophelia, driven out of her mind when her father is murdered by her lover Hamlet, falls into a stream and drowns… Shakespeare was a favourite source for Victorian painters, and the tragic-romantic figure of Ophelia from Hamlet was an especially popular subject, featuring regularly in Royal Academy exhibitions. Arthur Hughes exhibited his version of her death scene in the same year as this picture was shown (Manchester City Art Gallery).”

“There is a willow grows aslant a brook,

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream;

There with fantastic garlands did she come

Of crow-flowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name….

There, on the pendent boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious silver broke;

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spring wide;

And, mermaid-like awhile they bore her up…”(Shakespeare, 1599-1601/1978. Hamlet, 4.7).

Flower Symbolism in Shakespeare’s Plays

To learn more about the symbolism of flowers in Shakespeare’s plays, please open the link here.

To read and view Flowers from Shakespeare’s Gardens by Walter Crane, please open the Project Gutenberg eBook link here.

Additional Resources

Easy access to Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets can be found by opening the following links.

Boydell, J., & Boydell, J. (1803). A Collection of Prints, from pictures painted for the purpose of illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare, by the Artists of Great Britain. Engraving, print, illustration. Boydell Shakespeare Gallery (later published by Benjamin Blom, 1968). Please open the link here.

Buckle, L. (2010). Cambridge School Shakespeare: A midsummer night’s dream. Cambridge University Press.

Duncan-Jones, K. (2010). Shakespeare’s sonnets and A lover’s complaint. Arden Shakespeare.

Folger’s Shakespeare Website here.

Martineau, J. et al. (2003). Shakespeare in art. Merrell.

Project Gutenberg eBook of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Please open the link here.

Rowse, A.L. (1978). The annotated Shakespeare (Volumes 1-3). Clarkson N. Potter, Inc.

To read the complete text of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, please open the link here.