“Zacharie Vincent, known as Telariolin, was an Aboriginal artist (born 28 January 1815 in the village of Jeune-Lorette, Québec — formerly Village-Huron, today the Wendake Reserve; died 9 October 1886 in Québec City). His works, painted in the grand European style, were sold to visitors to Jeune-Lorette, soldiers from the British garrison and members of the political elite, such as Lord Elgin and Britain’s Princess Louise. Part of his oeuvre is conserved at the Château Ramezay Museum (Montréal), the Canadian Museum of History (Gatineau), and the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (Québec City), as well as in private collections.Zacharie Vincent was born into the Huron-Wendat community. Following epidemics and conflicts with the Iroquois, the Huron-Wendat migrated from the Great Lakes region to the Québec City region in the second half of the 17th century, living there under the protection of missionaries. After moving a number of times, the Wendat settled permanen”tly in Jeune-Lorette in 1697 and lived off hunting and the crafts and cottage industry. Vincent was the son of Chief Gabriel Vincent and Marie Otisse (Otis, Hôtesse). Among the colonial population, he had the reputation of being “the last pure-blooded Huron.” In 1845, he married an Iroquois widow named Marie Falardeau. They had four children: Cyprien (1848–95), Gabriel (b. and d. 1850), Zacharie (1852–55), and Marie (1854–84).”

Chapter 4: Indigenous, African American, and Transcultural Themes in Art and Related Texts

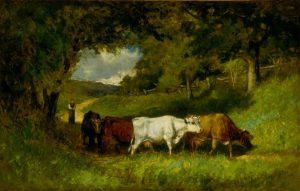

Viewing works of art from alternative and diverse vantage points can enrich learning experiences (Blackburn Miller, 2020; Greene, 2007; Lipson Lawrence, 2008; Magro and Sfeir, 2023). A 19th century landscape painting by John Frederick Kensett (see above), for example, can be viewed from one perspective as a stunning picture of the lush Hudson Valley. How have the geography, the people, the animals, and the environment been altered as a result of colonial settlements throughout the centuries? How have ancestral homelands be disrupted, transformed, and perhaps destroyed over time? Curators at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (2022) emphasize the importance of reassessing works of art from an Indigenous perspective. The Metropolitan Museum of Art In New York curators emphasize the importance of counter and alternative narratives that critically challenge Euro-American perspectives.

Indigenous artistic and historian Bonney Hartley (Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican) provides her insights into Kensett’s painting of the Hudson Valley:

Hidden Stories

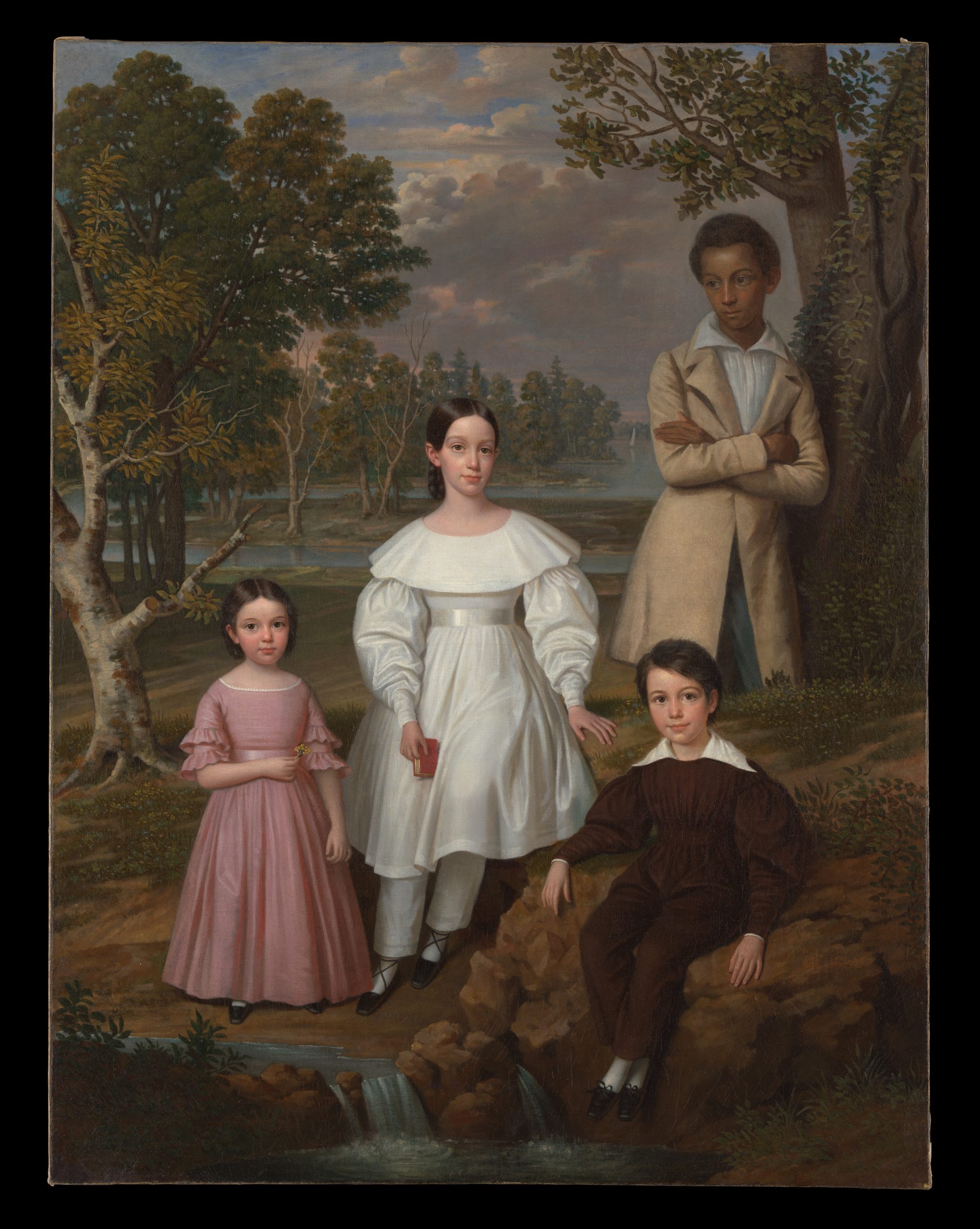

Guillieme Lucienne Amans’ (1837) Belizaire and the Frey Children (above) has been the focus of important discussions about the way in which art can illuminate, hide, or distort socio-cultural and historical information. Who is included in a particular portrait? Who is excluded and why? Recent historical research into this painting revealed the hidden story of an enslaved adolescent Belizaire. The painting (above) reflects an effort to erase and negate the presence of oppressed and enslaved individuals. The seeming domestic tranquility portrayed in the painting is in dramatic contrast to the fact that Belizaire was enslaved and could be sold (Belizaire had been sold to a family and after the family acquired the painting, had Belizaire painted out). The art collector and African American specialist Jeremy K. Simien bought the painting and had it expertly restored. Simien wanted to discover the identity of the youth (about fifteen years old at the time of the painting). The history of the painting and the art mystery surrounding the identity of the youth were explored (please refer to the video and historical origins of the painting). Research about the painting reveals that the work was more than likely commissioned by the New Orleans merchant Frederick Frey or his wife Coralie Frey. The painting was held in a garage and then later at the vaults of the Louisiana Art Museum in New Orleans, Lousiana. Ancestral records revealed that Belizaire was of “mixed race” and had been “bought and sold” to at least two families in the New Orleans area. Belizaire was responsible for the care of the Frey children. To read more about the history of this art work please open the link here.

Collective Memories and Overlooked Histories

Activist writer Robyn Maynard and artist and musician Leanne Betasamosake Simpson began writing each other letters during the pandemic. Their letters grew into a powerful exchange about the history of slavery, colonization, ecological destruction, and permanent and non-human health crises. Kelly writes that in Maynard and Simpson’s book Rehearsals for Living (2022) histories and collective memories of Black and Indigenous people are braided together in a way that establishes a basis for solidarity and a visionary plan for a more democratic and life-sustaining world. Kelly writes that Maynard and Simpson are not “mere dreamers” and that “they understand that the work of building the new world is no luxury—and that our very survival depends on turning dreams of decolonization and abolition into action” (Kelly, 2022, p. 273). Maynard and Simpson ask what it means to try “to build worlds that affirm, rather than destroy life” (Maynard & Simpson, 2022, p. 25). Simpson writes that she wants to live in a way “that doesn’t cause the extinction of vast numbers of plants and animals. Where extractive economies are not the norm and where capitalism is not assumed to be permanent. Where there are communal and embodied ethics and practices that make slavery and colonialism unthinkable, where one hundred musicians show up at busy intersections and no one is surprised” (Simpson, 2022, p. 199). From the perspective of Maynard and Simpson, students can explore art from an Indigenous perspective in terms of land dispossession, human rights violations, and the loss of language, culture, and livelihood that resulted from colonization. The idyllic landscapes of Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Cole, and Thomas Kensett can be viewed from a critical Indigenous perspective. Simpson (2022) emphasizes the importance of awareness and empathy from a land-based perspective:

What I learn from my ancestors is that if you have a profoundly different relationship with the land, with the earth—one grounded in diversity and based on consent, sharing, respect, and minimizing one’s impact, instead of mass exploitation of natural resources for the benefit a small group of people willing to exercise authoritarian power—you have a profoundly different relationship to all of life, profoundly different intimate relations, and profoundly different diplomatic relations.

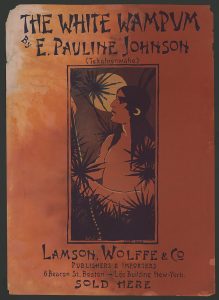

Explore the poetry of Emily Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake, 1861-1913) here. E. Pauline Johnson was a Mohawk (Six Nations of the Grand River, Haudennosaunee) poet, author, and dramatic stage performer. She was born just outside of Brantford, Ontario. Collectively Tekahionwake’s works drew not only on ancient Indigenous legends and oral traditions, but her poems and stories also celebrated Indigenous life and culture.

Fire-Flowers

“Fire Flowers” by Emily Pauline Johnson

And only where the forest fires have sped,

Scorching relentlessly the cool north lands,

A sweet wild flower lifts its purple head,

And, like some gentle spirit sorrow-fed,

It hides the scars with almost human hands.

And only to the heart that knows of grief,

Of desolating fire, of human pain,

There comes some purifying sweet belief,

Some fellow-feeling beautiful, if brief.

And life revives, and blossoms once again.

“The White Wampum” by E. Pauline Johnson

To learn more about E. Pauline Johnson, please open the link here.

Cover of “The White Wampum” by Ethel Reed (1874-1912). Library of Congress. Public Domain.

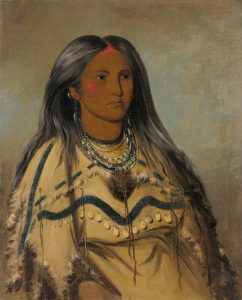

Metropolitan Museum Art Notes about the portrait of Hayne Hudjihini by Henry Inman.

Born into a prominent Eagle clan family of the Jiwere-Nut’achi (Otoe-Missouria) people, Hayne Hudjihini, Eagle of Delight, has a blue tattoo on her forehead denoting her royal status. Her marriage to Bear clan Chief Sumonyeacathee formed an Eagle-Bear union—a high honor among the Jiwere-Nut’achi people. Following a peace treaty in which the Jiwere-Nut’achi agreed to an alliance with the United States government, in 1822 she and her husband traveled as ambassadors and protectors of Jiwere-Nut’achi sovereignty from their home in present-day Nebraska to Washington, D.C., to meet with President James Monroe. During this trip, Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent Thomas McKenney is said to have fallen in love with her and commissioned her portrait. Despite Eagle clan members being known for their strength, health, and long lives, she died of measles shortly after she returned home.

Hiawatha

Additional Resources

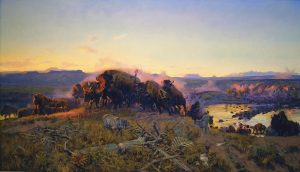

- For more information about the Bison/Buffalo that had been hunted to near extinction please open the link here.

- Treaties and Efforts to Restore the Bison to the Great Plains (Canadian Geographic)

- Bison and Buffalo: Endangered Speciese.

- Lesson Plan Ideas for Keepers of the Earth by Michael J. Caduto and Joseph Bruchac.

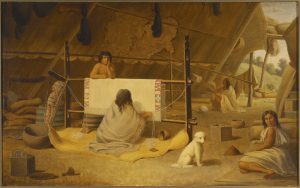

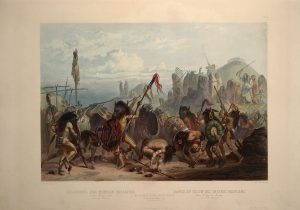

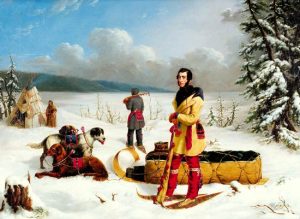

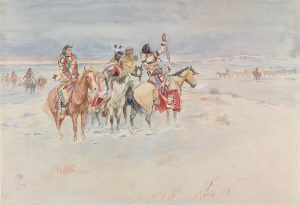

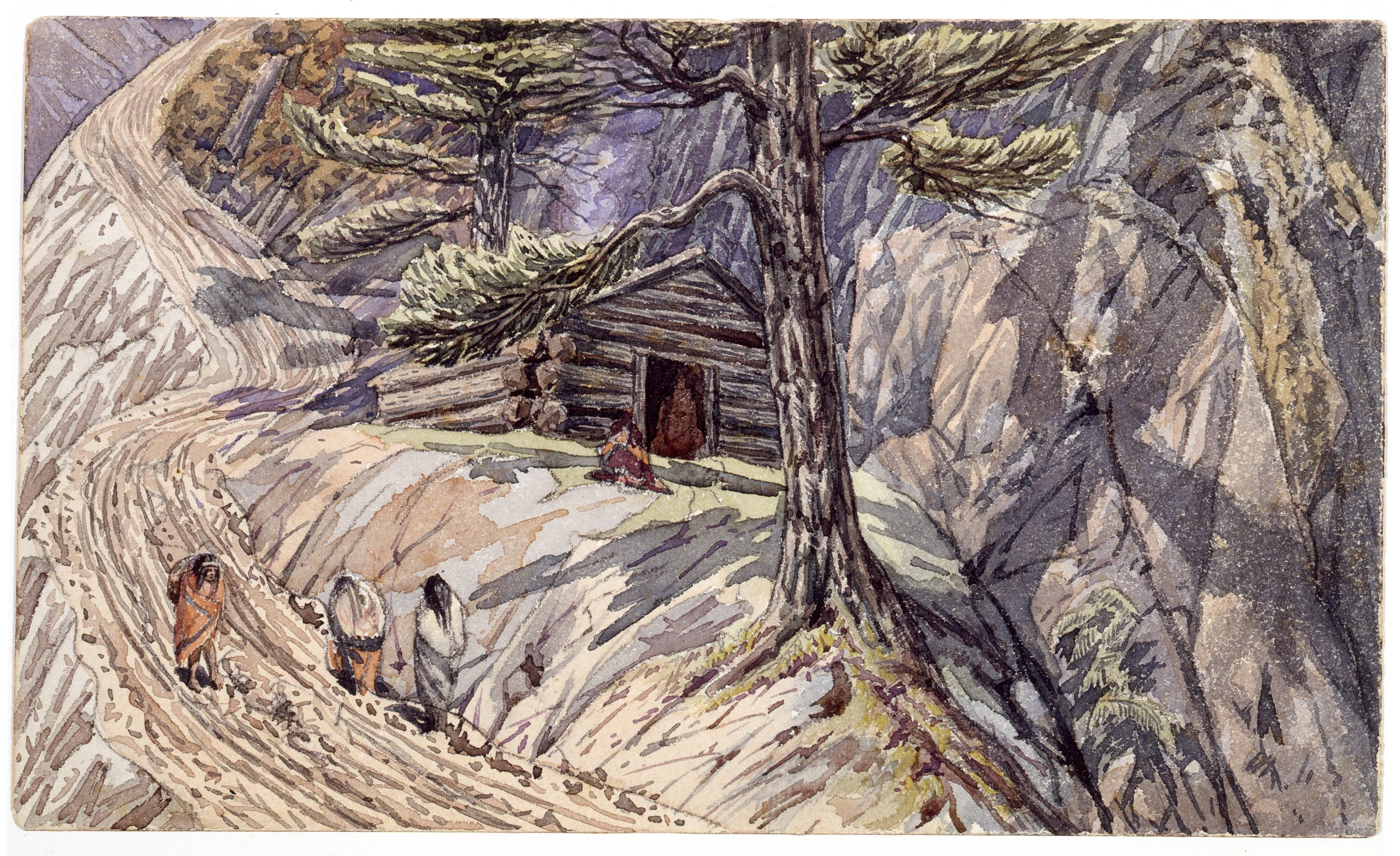

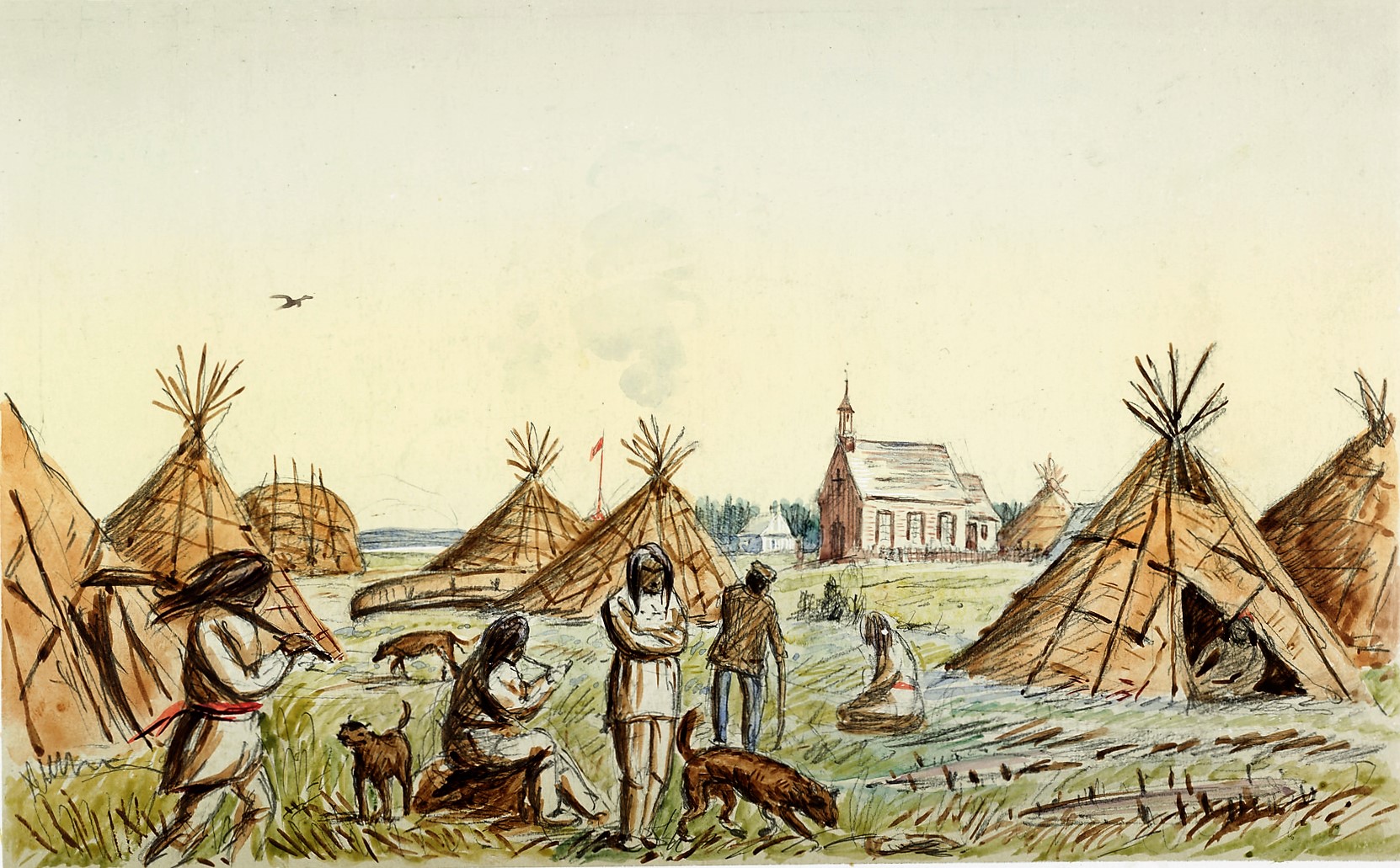

The artist Paul Kane (1810-1871) had immigrated with his family from Ireland to Canada in 1819. Kane’s dramatic portraits of Indigenous people, fur traders, surveyors, migrants, and missionaries in addition to his panoramic landscape paintings of Canada and other parts of North America continue to be of important ethnographic and historical value. Influenced, in part, by the paintings of George Caitlin (1796-1872), Kane was the first and only Canadian artist to embark on both a pictorial and literacy project that documented the customs, artefacts, dress, lifestyles, and manner of Indigenous people before photography became a dominant medium. Paul Kane’s (1859) Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North American from Canada to Vancouver’s Island to Oregon through the Hudson Bay Company’s territory and back again included diary entries and sketches recounting his adventures and experiences. In the preface, Kane explained that his book was “designed to illustrate the manner and customs of the Indian Tribes of British America. The principle object in my undertaking was to sketch pictures of the principal chiefs and their original costumes, to illustrate their manners and customs, and to represent the scenery of an almost unknown country” (Kane, 1859, Preface, Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America). Kane wanted to illuminate his experiences that could be of “intrinsic value to the historian” as “they related not only to the vast tract of country bordering on the great chain of American lakes, the Red River settlement, the valley of “Sascatchawan” [Saskatchewan], and its boundless prairies through which it is proposed to lay the great railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, through the British possessions; but also across the Rocky Mountains down the Columbia River to Oregon, Puget’s Sound and Vancouver Island, where the recent gold discoveries in the vicinity have drawn thousands of hardy adventures” (Kane, 1859, pp. viii-ix).

In both his paintings and diaries, Kane countless adventures as he travels through the vast and rugged terrain of North America; he describes meetings with different Indigenous people; he describes the wholesale and tragic slaughter of buffalo across the planes, and the increasing threat to the traditional way of life and customs of different Indigenous groups during the fur trade years. Critics comment that parts of Kane’s book were ghostwritten and that his art romanticizes the harsh reality of life for many Indigenous people at the time. Nevertheless, as Arlene Gehmacher (2023) emphasizes, the work of Paul Kane is still highly significant and valuable as an ethnographic record and as a unique artistic expression.

Exploring Paul Kane’s work from a 21st century lens can provide a unique perspective on settler-colonial relations with Indigenous people. Kane’s work can be re-examined by analyzing narratives and themes related to Indigenous people, Human Rights, and restorative justice for Indigenous people (please refer to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission). Homeland displacement, cultural and linguistic annihilation, and the the ongoing threat Indigenous peoples experienced as colonial settlements expanded across Canada and throughout North America can be explored from an artistic lens of painters like Paul Kane. Kane’s work can be analyzed from an environmental lens as habitat destruction which brought the buffalo to near extinction and which continued to jeopardize the livelihood of Indigenous people continued to be a critical concern. The work of visionary artists such as the mystic artist Norval Morrisseau and contemporary artists such as Kent Monkman, and Christi Belcourt can be further explored to contrast idealized versions of Indigenous people and their way of life and the realities of Indigenous experiences portrayed by visionary and contemporary Indigenous artists.

- To explore more Indigenous art from the Art Gallery of Ontario please open the link here

- To learn more about the following Indigenous artist please click on the links below:

- Norval Morrisseau

- David Ruben Piqtuoukun

- Daphne Odjig

- Haida Artist Bill Reid

- First Nations and Metis Artists

- Indigenous Art in Canada

- Indigenous Artists in Canada

- Anishanaabe Art Posters (Ontario College of Teachers-“Explore Professional Practice through Anishanaabe Art”)

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Canada: Truth and Reconciliation Teaching Resources

- Quamajug (Inuit Art, Winnipeg Art Gallery, WAG, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada)

- Inuit artist Goota Ashoona created “Tuniigusiia”/“The Gift,”2020, one of the largest Inuit sculptures in the world for the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

- Educator’s Guide for Read-Listen-Tell: Indigenous Stories from Turtle Island

- Books to Read for National Indigenous History Month

- Teaching Indigenous Texts

- Indigenous Artists in Canada

- Indigenous Texts

- Teaching Indigenous Learners/ Indigenous Themes

- Keepers of the Earth: Native American Stories and Environmental Activities for Children

- Keepers of the Earth: Teacher’s Guide

- Smithsonian American Art Museum:National Museum of the American Indian

- For more information about Paul Kane, please open the link here.

The Manifest Destiny belief that colonists were “divinely ordained” masters of the North American content (and other lands colonized) ignored the dire consequences that destroyed Indigenous peoples, their lands and livelihood. Paintings by Albert Bierstadt, Frederick Church, George Innes, and Robert Duncanson exhibited their works to notable claim but the reality of the way the land had been usurped and exploited was largely ignored. Their art shaped the visual identity of North America and beyond. In viewing these landscape paintings from a 21st century lens, it is vital to explore and understand the complex bio-history of each region-the lands, its people, the animal inhabitants, forest, flowers, and fauna. What has happened to this land and its peoples today? How was this land viewed by Indigenous Peoples? To what extent has any of the land been restored and the rights of its inhabitants protected? What more can be done to ensure that further land degradation does not continue? How have the rights of Indigenous Peoples been protected? In their book Rehearsals for Living, Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (2022) write that Indigenous and Black lives are interconnected and that their “unfinished histories” must acknowledge and include the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their lands and the destruction and land and wildlife “in the service of capital and white settlement” (p.23). Robyn Maynard (2022) writes:

Wendat-Huron Indigenous Women’s Arts: Transforming Narratives into Everyday Use

The beautiful embroidery art created by Indigenous Wendat women was also an important record that reflected ancestral Indigenous knowledge for families, clans, and communities. Many Indigenous artists and artisans were unknown despite the fact that their work was so central to the social and cultural foundation of the community. The Huron-Wendake people lived in a bordering area of Ontario and Quebec in the region by Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. As a result of the 17th century beaver wars, the Huron-Wendat people moved east to Quebec City. Huron-Wendat artists such Marguerite Vincent Lawinonkié (1783-1865) created intricate embroidery using porcupine quill beads, moosehair, textiles, and birch bark. These stunning and multicolored designs were woven into valuable gifts and everyday clothing including embroidered snowshoes, moccasins, coats, mittens, and pouches. Together with her husband, son and nephew, Lawinonkie began a larger scale manufacturing of snowshoes, moccasins, and mittens for the military. In her groundbreaking book Wendat Women’s Arts, Annette W. de Stecher (2022) explains that women artists like Marguerite Vincent Lawinonké helped develop and secure the economy of the Huron-Wendat community in Quebec by teaching the skill of bead and quill work; as a result, a successful local economy developed around moccasin and snowshoe production and by 1879, de Stecher explains that at least sixty of the 76 families in Wendake ( Huron Wendake Nation, La Haute-Saint-Charles, Quebec) made a living from local goods production. The Huron-Wendat and other Indigenous women had the skills and the tools before colonial contact to create works of art in pottery and textiles. Post-contact, these artisans and artists were able to adapt and adopt new techniques and embroidery stitches from their interactions with the Europeans.

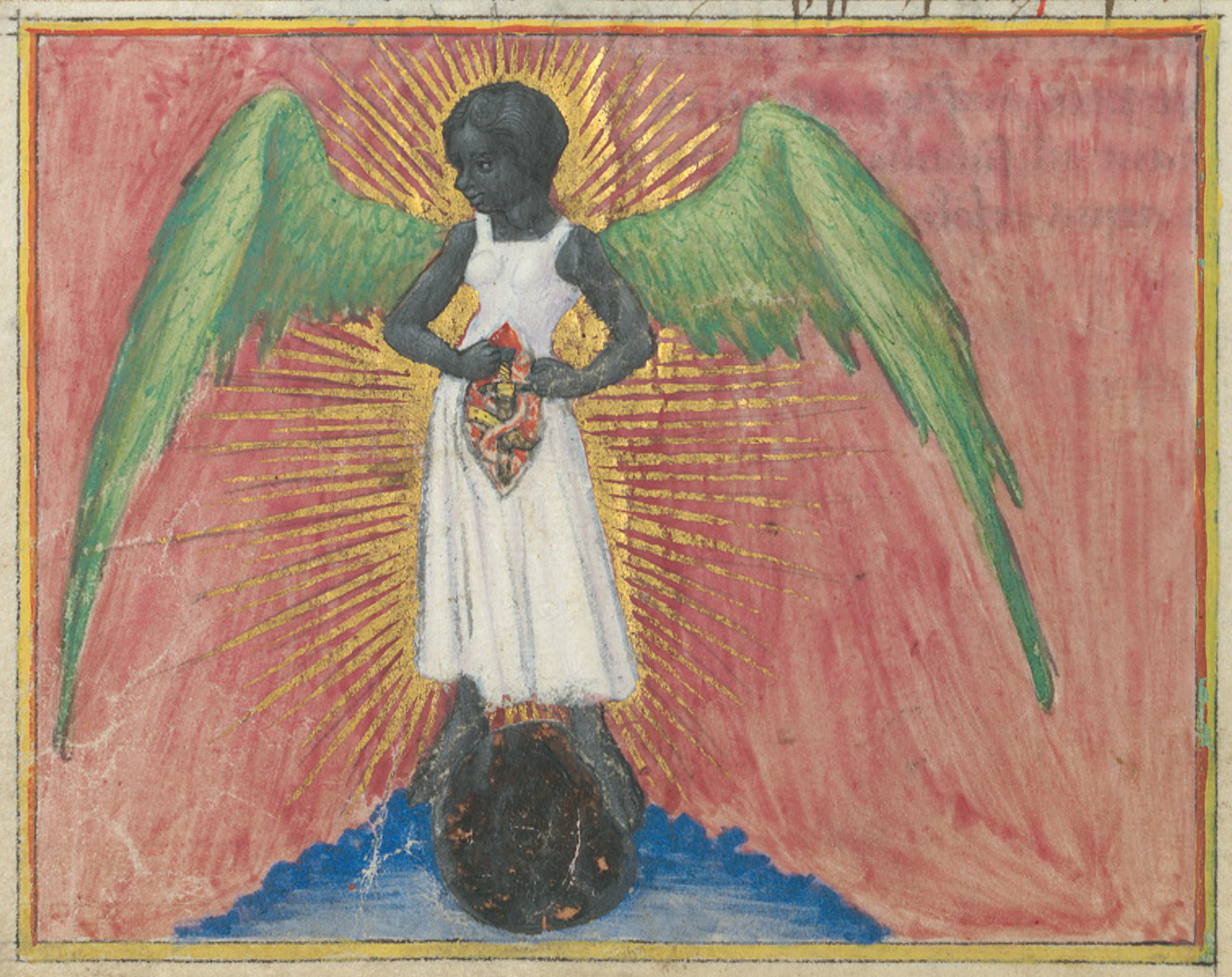

The Wendat-Huron art reflected Indigenous cultural beliefs and a cosmology where non-human beings had a spirit and importance to life and wellbeing. “In the Wendat worldview, everything is animate and possesses a soul” (de Stecher, 2022, p. 35). Through oral traditions and ancestral knowledge, the Huron-Wendat women artists transformed material from the land into beautiful and useful objects. The symbols and motifs evident in the intricate embroidery were visual metaphors “embodied the spiritual and animate qualities of their animal and plant sources, as well as family relationships and connections to the land” (de Stecher, 2022, p.16). The hourglass was a symbol of the sky world while the spiral symbol represented the underworld. Colours such as white and green were associated with life, vibrancy, knowledge, and cognitive powers while black was connected with death, mourning, and isolation. Red was associated with intense experience, emotion, and animation. Strawberries or “tichionte” (translated to mean “stars”) were thought to be “heaven sent” and were connected to healing as well as spiritual and physical renewal, transformation, and rebirth. Blue represented the vast skies as well as purity and clarity. This vibrant palette of colours found its way into the designs of moccasins, purses, pouches, mittens, coats, and other items of dress. Brightly coloured shelled or crystals, copper, and other precious material were connected with longevity and a spiritual and emotional well-being. With increasing interactions with European travelers, settlers, priests, nun, and military personnel, the artwork by Wendat women became important gifts and symbols of reciprocity and peace. de Stecher (2022) explains that the Huron-Wendat society was matrilineal and that women played key leadership roles in the geopolitical environment. Their independence and authority impacted family systems, clans, and nations.Women were responsible for key decision making in the social and economic life of the community both pre-and post- colonial contact. Embroidery and birch bark gifts symbolized alliances, trust, and reciprocity. Their vibrant art represented forms of cultural continuity that linked the past to the present and future generations. In the Wendat story of creation, the birds (in the form of geese, swans, loons, or seagulls) rescued the Sky woman when she fell from the sky and landed on the giant turtle’s back (see Wendat story of creation below). The divine and the earthly were interconnected. de Stecher notes that the myths of creation, and the legends passed down through generations all find their way into the symbols and motifs of animals, plants, trees, and the cosmos in the Wendat women’s art:” The Wendat creation story presents a worldview in which women were creators, humankind depended on cosmological forces and on the land, and sentient nonhuman persons—animals, plants, and the physical elements of the land—had souls or spirits and protected humans so that they could survive and thrive. This it was critically important to maintain relations with all categories of beings. Women’s arts were intermediaries that helped to achieve this aim. Dress embroidered with moosehair and quills connected the wearer with cosmological forces and with the animate natural world. Aataentsic (Sky Woman) was identified with the moon, and her grandson Tsestah, protector of the warriers, was identified with the sun. A pair of men’s moccasins worked with rows of half-moons and circles related the wearer to Aataentsic and the Sky World’s dome of heaven, as well as to Tsestah and the sun. Women transmitted the belief system through the motifs of their embroidered bark work…”(de Stecher, 2022, p. 3-4).

“Deyhandiaouich Deyawennake” The Wendat World Creation Story

The Huron-Wendat creation story derived from a series of stories and a translation of Heron-Wendat creation stories by Marius Barbeau in 1904. The full length Heron-Wendat Creation Story can be found on pp. 37-41 in The Huron & Wyandot Mythology by C.M. Barbeau in 1915 (pp. 37-42).Excerpt adapted by Mireille Siouï:

“A long time ago, our Wendatpeople lived in the sky. One day, a great disaster happened and the ground Asank. Then, a Tree and a Woman fell through into the Great Water World. At that time, large White Birds were swimming. When they saw the Falling Woman, they formed a circle, ready to receive her onto their feathered backs. Suddenly, for the first time in this world, a Flash of Lightning was seen and Henon, the Thunder’s Big Voice was heard. Surprised, all the aquatic Animals gathered together. They decided to create an Island where the Woman will live and Handiaouich, the Big Turtle, the oldest of them, will bring the Island on her back.” One by one, Tawanda, the Otter, Ondatra, the Muskrat and Stoutaye, the Beaver dived into the deep water and tried to retrieve some earth trapped by the Sky Tree’s roots. ….”

Huron-Wendat Artist Zacharie Vincent (1815-1886)

Cree Métis Flower Art Embroidery Art

The Cree Métis Indigenous people of the Red River Settlement, a colony on the banks of the Red River near the mouth of the Assiniboine River (in what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba) created beautiful floral designs embroidered into moccasins, snowshoes, mittens, tobacco pouches, saddles, gloves, vests, and coats. While many of the geometric designs were passed down from their Cree ancestors (pre-contact) using porcupine quills, some of the skills were learned from the Grey Nuns who worked as teachers and nurses in Manitoba and in other missions across Canada. Patrick Young (2023) writes that the “origin of Cree-Métis beadwork designs came from experimentation and merging of various art traditions that influenced Métis style. Several Plains First Nations used geometric patterns on their tipi covers, parfleches and clothing and, up until the 1840s Métis decoration was dominated by geometric designs” (p.3). Indigenous Cree-Métis beadwork artist, poet, memoirist and University of Victoria writing professor Gregory Scofield (2021) explains that by the 19th century Indigenous people faced major obstacles including racism and land displacement and so many communities ended up impoverished. “Women were sewing as supplemental income to support families, and a lot of those pieces ended up in the tourist trade” (p.1). He explains that too often, museums, worldwide, categorize the beadwork as a type of “Victoriana” or labelled as “crafts.” Scofield wants to repatriate these valuable and beautiful works of art to their ancestral homes. He continues to research the story behind the beadwork. Scofield explains that “by misidentifying the beadwork the stories and geography are stripped away, and communities are stripped of their identity too.” (p.2). Each work from the perspective of Scofield is an expression of creativity and an Indigenous world-view. Increasingly, the work of the Cree-Metis who were also known in the 19th century as the “Flower Beadwork People” are valued for their beauty, artistry, and insight into Indigenous ways of knowing.The intricate floral designs can also be seen in the embroidery art work by the Cree-Métis artists. Contemporary artists such as Christi Belcourt have brought new life to the floral embroidery art forms. Belcourt explains that not only is her art honoring ancestral traditions, but she is highlighting the importance of connecting art to the lands and all beings today. Awareness and empathy for all “mother nature” can open up new possibilities for learning and creativity. She explains:

All Indigenous art traditions come from an understanding of, and connection with, the land and its spirits. So that knowledge is encoded in the work or art. When you look at Indigenous art around the world, there is always that direct connection to the land. That understanding of how we’re supposed to live on the land is encoded into the design, the symbols and the things that we see.It’s no different with beadwork. So when I’m creating my art, it’s not a simple transferring of the beadwork patterns onto the canvas; it has to have the meaning behind it. So there will be certain plants or symbols in the painting that have a specific reason or coding behind them. It’s always a message about the respect for lands and waters: the respect we need to have for the earth and everything that is around us. As human beings, we are mistaken if we think we are superior to other species. (2023).

Belcourt’s distinctive tapestries integrate traditional beadwork imagery with contemporary themes that celebrate the reverence for life, the importance of resilience and resistance, overcoming obstacles, and struggle for Indigenous identity.(Source: Threlfall, 2021, “Beadwork as resistance.” University of Victoria, Fine Arts.Cree-Metis Art

Cleveland Museum Art Notes:“This colorful bag is beaded on both sides. On one side, the flowers resemble the sun, which native peoples of the Woodlands regard as the supreme spirit; the visual parallel is probably intentional. On the other side, a different plant symmetrically spreads its leaves and flowers across a dark, contrasting ground.”Native American Textiles: Cleveland Museum of Art

Additional Resources

Metis MuseumMetis Museum Beadwork

The Canadian Encyclopedia information about Christi Belcourt

An Interview with Christi BelcourtTo see a Cree Métis bag, ca. 1875. Manitoba, Canada. Wool cloth, beads, silk; 42 x 35 cm. Mrs. E. C. McDonald Collection. 15/1692 from the National Museum of the American Indian (Smithsonian, Washington, DC) and the “Infinity of Nations Collections” please open the link here.

Indigenous Themes in 19th Century and Early 20th Century Art

Museum Notes

Métis buffalo hunt on the prairies of Dakota in June 1846. The man lying on the ground is Kane himself. Compare the clothing with that on Kane Prairie.jpg, and Kane reported in his travel account that he fell from the horse and got nearly run over by the buffalos, but was saved from that fate by one of the Métis who chased the animals around him and shielded him from the herd. Despite this incident, Kane managed to kill two bisons himself. The scene obviously is from the Métis buffalo hunt in June 1846 as they run the buffalos by horse on the open prairie; the later buffalo hunts Kane witnessed were either a Cree pound hunt (between Ft. Carlton and Ft. Edmonton on the north side of the North Saskatchewan River), or hunts with HBC people, but these occurred in winter 1847/48 at Ft. Edmonton.” (Royal Ontario Museum of Art, Toronto, Ontario).

For more information about Paul Kane, please open the link here.

Further Reading:The White Buffalo Calf Woman and the Sacred Pipe (Lakota-Sioux-Great Plains)

Illustrated Texts of Indigenous Myths and Legends There are a number of fascinating early 20th century texts of Indigenous myths and legends that have been transcribed from oral storytelling traditions to print. The stories excerpted below are from The myths of North American Indians by Lewis Spence (1874-1955) and illustrated by James Jack (late 19th and early 20th century illustrator). The legends and myths include stories of transformation, creation myths, and varied legends from Algonquin, Iroquois, Sioux, and Pawnee Indigenous peoples. Supernatural and mystical themes reflect interconnections between humans, animals, the land, the waters, and the cosmos. Collectively, these legends and myths provide an insight into Indigenous beliefs and world views. Contemporary texts such as Keepers of the Earth: Native American Stories and Environmental Activities for Children can be a valuable guide to connecting Indigenous myths and legends to interdisciplinary studies such as education for sustainability, world issues, anthropology, and English language arts.In reading and analyzing 20th and 19th century accounts of European and British writers and translators the colonial bias, racist beliefs, and a misunderstanding Indigenous ways of knowing. The assimilationist policies that were prevalent throughout the North America worked to destroy and erode Indigenous communities, languages, livelihoods, and ways of being. A paternalistic and condescending tone suggesting that the white settler colonialists are brining “enlightenment” to Indigenous people negates the complex Indigenous world view as well as the established communities with linguistic diversity and philosophies that emphasize a close interconnected relationship with nature (versus control over the natural world):

After the establishment of the United States Government a number of Christian and lay bodies undertook the education and enlightenment of the aborigines. Until 1870 all Government aid for this object passed through the hands of missionaries, but in 1775 [Transcriber’s note: 1875?] a committee on Indian affairs had been appointed by Congress, which voted funds to support Indian students at Dartmouth and Princeton Colleges. Many day-schools were provided for the Indians, and these aimed at fitting them for citizenship by inculcating in them the social manners and ethical ideas of the whites. The school established by Captain R. H. Pratt at Carlisle, Pa., for the purpose of educating Indian boys and girls has turned out many useful members of society. About 100 students receive higher instruction in Hampton Institute. There are now 253 Government schools for the education of Indian youth, involving an annual expenditure of five million dollars, and the patient efforts of the United States Government may be said to be crowned with triumph and success when the list of cultured Indian men and women who have attended these seminaries is perused. Many of these have achieved conspicuous success in industrial pursuits and in the higher walks of life.” (p.79).

Story Excerpts from The myths of North American Indians collected by Lewis Spence, for more information, please open the link here.

“The Healing Waters” (pp. 258-261)

The Iroquois have a touching story of how a brave of their race once saved his wife and his people from extinction.It was winter, the snow lay thickly on the ground, and there was sorrow in the encampment, for with the cold weather a dreadful plague had visited the people. There was not one but had lost some relative, and in some cases whole families had been swept away. Among those who had been most sorely bereaved was Nekumonta, a handsome young brave, whose parents, brothers, sisters, and children had died one by one before his eyes, the while he was powerless to help them. And now his wife, the beautiful Shanewis, was weak and ill. The dreaded disease had laid its awful finger on her brow, and she knew that she must shortly bid her husband farewell and take her departure for the place of the dead. Already she saw her dead friends beckoning to her and inviting her to join them, but it grieved her terribly to think that she must leave her young husband in sorrow and loneliness. His despair was piteous to behold when she broke the sad news to him, but after the first outburst of grief he bore up bravely, and determined to fight the plague with all his strength.”I must find the healing herbs which the Great Manitou has planted,” said he. “Wherever they may be, I must find them.”So he made his wife comfortable on her couch, covering her with warm furs, and then, embracing her gently, he set out on his difficult mission.All day he sought eagerly in the forest for the healing herbs, but everywhere the snow lay deep, and not so much as a blade of grass was visible. When night came he crept along the frozen ground, thinking that his sense of smell might aid him in his search. Thus for three days and nights he wandered through the forest, over hills and across rivers, in a vain attempt to discover the means of curing the malady of Shanewis.When he met a little scurrying rabbit in the path he cried eagerly: “Tell me, where shall I find the herbs which Manitou has planted?”But the rabbit hurried away without reply, for he knew that the herbs had not yet risen above the ground, and he was very sorry for the brave.Nekumonta came by and by to the den of a big bear, and of this animal also he asked the same question. But the bear could give him no reply, and he was obliged to resume his weary journey. He consulted all the beasts of the forest in turn, but from none could he get any help. How could they tell him, indeed, that his search was hopeless?

“The Pity of the Trees”On the third night he was very weak and ill, for he had tasted no food since he had first set out, and he was numbed with cold and despair. He stumbled over a withered branch hidden under the snow, and so tired was he that he lay where he fell, and immediately went to sleep. All the birds and the beasts, all the multitude of creatures that inhabit the forest, came to watch over his slumbers. They remembered his kindness to them in former days, how he had never slain an animal unless he really needed it for food or clothing, how he had loved and protected the trees and the flowers. Their hearts were touched by his courageous fight for Shanewis, and they pitied his misfortunes. All that they could do to aid him they did. They cried to the Great Manitou to save his wife from the plague which held her, and the Great Spirit heard the manifold whispering and responded to their prayers.

She sang a strange, sweet song “While Nekumonta lay asleep there came to him the messenger of Manitou, and he dreamed. In his dream he saw his beautiful Shanewis, pale and thin, but as lovely as ever, and as he looked she smiled at him, and sang a strange, sweet song, like the murmuring of a distant waterfall. Then the scene changed, and it really was a waterfall he heard. In musical language it called him by name, saying: “Seek us, O Nekumonta, and when you find us Shanewis shall live. We are the Healing Waters of the Great Manitou.”Nekumonta awoke with the words of the song still ringing in his ears. Starting to his feet, he looked in every direction; but there was no water to be seen, though the murmuring sound of a waterfall was distinctly audible. He fancied he could even distinguish words in it. “Release us!” it seemed to say. “Set us free, and Shanewis shall be saved!” Nekumonta searched in vain for the waters. Then it suddenly occurred to him that they must be underground, directly under his feet. Seizing branches, stones, flints, he dug feverishly into the earth. So arduous was the task that before it was finished he was completely exhausted. But at last the hidden spring was disclosed, and the waters were rippling merrily down the vale, carrying life and happiness wherever they went. The young man bathed his aching limbs in the healing stream, and in a moment he was well and strong.Raising his hands, he gave thanks to Manitou. With eager fingers he made a jar of clay, and baked it in the fire, so that he might carry life to Shanewis. As he pursued his way homeward with his treasure his despair was changed to rejoicing and he sped like the wind.When he reached his village his companions ran to greet him. Their faces were sad and hopeless, for the plague still raged. However, Nekumonta directed them to the Healing Waters and inspired them with new hope. Shanewis he found on the verge of the Shadow-land, and scarcely able to murmur a farewell to her husband. But Nekumonta did not listen to her broken adieux. He forced some of the Healing Water between her parched lips, and bathed her hands and her brow till she fell into a gentle slumber. When she awoke the fever had left her, she was serene and smiling, and Nekumonta’s heart was filled with a great happiness.The tribe was for ever rid of the dreaded plague, and the people gave to Nekumonta the title of ‘Chief of the Healing Waters,’ so that all might know that it was he who had brought them the gift of Manitou. (Spence, 1914, pp. 258-261)

How the Rabbit Slew the Devouring Hill

from The Myths and Legends of North American Indians byIn the long ago there existed a hill of ogre-like propensities which drew people into its mouth and devoured them. The Rabbit’s grandmother warned him not to approach it upon any account.But the Rabbit was rash, and the very fact that he had been warned against the vicinity made him all the more anxious to visit it. So he went to the hill, and cried mockingly: “Pahe-Wathahuni, draw me into your mouth! Come, devour me!”But Pahe-Wathahuni knew the Rabbit, so he took no notice of him.Shortly afterward a hunting-party came that way, and Pahe-Wathahuni opened his mouth, so that they took it to be a great cavern, and entered. The Rabbit, waiting his chance, pressed in behind them. But when {303} he reached Pahe-Wathahuni’s stomach the monster felt that something disagreed with him, and he vomited the Rabbit up.

Once more the Rabbit entered, disguised as a man. Later in the day another hunting-party appeared, and Pahe-Wathahuni again opened his capacious gullet. The hunters entered unwittingly, and were devoured. And once more the Rabbit entered, disguised as a man by magic art. This time the cannibal hill did not eject him. Imprisoned in the monster’s entrails, he saw in the distance the whitened bones of folk who had been devoured, the still undigested bodies of others, and some who were yet alive.Mocking Pahe-Wathahuni, the Rabbit said: “Why do you not eat? You should have eaten that very fat heart.” And, seizing his knife, he made as if to devour it. At this Pahe-Wathahuni set up a dismal howling; but the Rabbit merely mocked him, and slit the heart in twain. At this the hill split asunder, and all the folk who had been imprisoned within it went out again, stretched their arms to the blue sky, and hailed the Rabbit as their deliverer; for it was Pahe-Wathahuni’s heart that had been sundered.The people gathered together and said: “Let us make the Rabbit chief.” But he mocked them and told them to be gone, that all he desired was the heap of fat the hill had concealed within its entrails, which would serve him and his old grandmother for food for many a day. With that the Rabbit went homeward, carrying the fat on his back, and he and his grandmother rejoiced exceedingly and were never in want again. (Spence, 1914, pp. 302-304)

Excerpt from Anonymous, Folk-lore and legends of the North American Indian, 1890, W.W. Gibbons.

There were once ten brothers who hunted together, and at night they occupied the same lodge. One day, after they had been hunting, coming home they found sitting inside the lodge near the door a beautiful woman. She appeared to be a stranger, and was so lovely that all the hunters loved her, and as she could only be the wife of one, they agreed that he should have her who was most successful in the next day’s hunt. Accordingly, the next day, they each took different ways, and hunted till the sun went down, when they met at the lodge. Nine of the hunters had found nothing, but the youngest brought home a deer, so the woman was given to him for his wife.

The hunter had not been married more than a year when he was seized with sickness and died. Then the next brother took the girl for his wife. Shortly after he died also, and the woman married the next brother. In a short time all the brothers died save the eldest, and he married the girl. She did not, however, love him, for he was of a churlish disposition, and one day it came into the woman’s head that she would leave him and see what fortune she would meet with in the world. So she went, taking only a dog with her, and travelled all day. She went on and on, but towards evening she heard some one coming after her who, she imagined, must be her husband. In great fear she knew not which way to turn, when she perceived a hole in the ground before her. There she thought she might hide herself, and entering it with her dog she suddenly found herself going lower and lower, until she passed through the earth and came up on the other side. Near to her there was a lake, and a man fishing in it.

“My grandfather,” cried the woman, “I am pursued by a spirit.”

“Leave me,” cried Manabozho, for it was he, “leave me. Let me be quiet.”

The woman still begged him to protect her, and Manabozho at length said—

“Go that way, and you shall be safe.”

Hardly had she disappeared when the husband, who had discovered the hole by which his wife had descended, came on the scene.

“Tell me,” said he to Manabozho, “where has the woman gone?”

“Leave me,” cried Manabozho, “don’t trouble me.”

“Tell me,” said the man, “where is the woman?” Manabozho was silent, and the husband, at last getting angry, abused him with all his might.

“The woman went that way,” said Manabozho at last. “Run after her, but you shall never catch her, and you shall be called Gizhigooke (day sun), and the woman shall be called Tibikgizis (night sun).”

So the man went on running after his wife to the west, but he has never caught her, and he pursues her to this day” (Gibbons, 1890, pp. 74-75).

Manabozho or Nanabozho, the shape-shifting trickster god, was also known as the “Great Hare” in Ojibwe and Anishinaabe culture. The stories of Nanabozho or Manabozho often have a moral lesson.

“Nanabozho is a shapeshifter who is both zoomorphic as well as anthropomorphic, meaning that Nanabozho can take the shape of animals or humans in storytelling.[5] Thus Nanabush takes many different forms in storytelling, often changing depending on the tribe. The majority of storytelling depicts Nanabozho through a zoomorphic lens. In the Arctic and sub-Arctic, the trickster is usually called Raven. Coyote is present in the area of California, Oregon, the inland plateau, the Great Basin, and the Southwest and Southern Plains. Rabbit or Hare is the trickster figure in the Southeast, and Spider is in the northern plains. Meanwhile, Wolverine and Jay are the trickster in parts of Canada. Often, Nanabozho takes the shape of these animals because of their frequent presence among tribes. The animals listed above have similar behavioral patterns. For example, they all live near human settlements and are very cunning, enough so as to be captured with great difficulty.” (Wikipedia).

The Cree-Métis Floral Beadwork People

- Folklore and legends of North American Indians by Anonymous (published in 1890; W.W. Gibbins), 2021, Project Gutenberg. 2007,

- Haida Myths by Marius Barbeau (1953).

Metropolitan Museum of Art Indigenous Perspectives on Art: Jeremy Dennis, a member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation describe this scene from an Indigenous perspective:This work depicts a leisurely beach scene painted one year after Chase opened a school of art near the Shinnecock Indian Reservation on Long Island’s East End. This land is situated on the Shinnecock people’s ancestral territory—of which more than 4,422 acres was stolen through an illegal transaction in 1859. The school and Chase’s stay on Long Island were devised by Mrs. Janet S. Hoyt, a wealthy patron of the arts and an artist who lived in the Shinnecock Hills. Hoyt proposed a summer employment opportunity for Chase with the end goal of developing a real-estate venture and transforming the area into a summer-resort destination. Despite the increased eagerness to settle in the Shinnecock Hills, the Shinnecock Indian Nation has remained vigilant in asserting their rightful title to their ancestral land.Richard Wagamese’s Embers (2016) juxtaposes nature photographs with his own personal meditations on life and the universe. Wagamese writes that “we live because everything else does. If we were to choose collectively to live that teaching, the energy of our consciousness would heal each of us—and heal the planet” (p.36). Texts like these can be applied in a creative way in the classroom. Students might be involved in both self-directed and collaborative ventures. Being observant, writing nature reflections, taking photographs of nature around them, and then documenting the way their own community nurtures the natural environment can be part of a self-directed or collaborative research venture that culminates in a photography exhibit of student work or a formal presentation. A skillful integration of projects can raise social and global awareness of planetary reverence and sustainability. Research papers, presentations, photographic collages, and landscape/nature paintings may be some of the creative projects that students embark upon. Place-based education can be described as a “pedagogy of community” that might “inspire stewardship, love for home place whether urban or rural, and an authentic renewal and revitalization of civic responsibility that brings education back to the neighborhood” (Bruce, 2011, p. 21). Transformational teaching involves teaching creatively:”Place-based education challenges the meaning of education by asking ‘Who am I? What is the nature of this place? What sustains this community? It often employs a process of re-storying, whereby students are asked to respond creatively to stories of their home ground, so that, in time, so that they are able to position themselves, imaginatively and actually, within the continuum of nature and culture in that place. They become part of the community rather than a passive observer.” (Lane-Zuker, 2004 cited in Bruce, 2011, p.21)..From a place-based learning perspective, creative teaching in English language arts can encourage a search for knowledge, a sense of wonder, a reverence for all life forms, and an appreciation for living. “Without that affinity and nourishment of a sense of kinship with all living things, literacy of any other sort will not help that much “(Bruce, 2011,p.15). Creative literacy learning nurtures curiosity, observation, close attention, learning to theorize, and learning to communicate. The varied art landscape paintings in this chapter section can be a starting point for further exploration.

Additional Resources.

- Dungy, C. (2009). Black nature poetry: Four centuries of African American nature poetry. Athens: University of Georgia.Ecopoetics.Matsumoto, L. (2016).

- Wordsworth and Basho: Walking Poets: Encounters with Nature. Kakimori Bunko, ITami, Japan.McGill University. Artists learning through poety and ecopoetry. Wilson, S. (2023).

- Ecopoetry: An Introduction. Companion to environmental studies, studies. Wikipedia

Poetic and Art Inspiration from the Harlem Renaissance Poets The Harlem Renaissance poets Langston Hughes (1902-1967), Countee Cullen (1903-1946) and Jean Toomer (1894-1967) wrote poetry that spoke to dislocation, belonging and identity, diaspora, and oppressive land-relations under conditions of slavery and rural poverty. Some of their poems can be viewed from an ecocritical perspective. The Ecopoetry Anthology (2013) edited by Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Grey Street can provide examples of poetry written that addresses dislocation, oppression, slavery, and environmental devastation. The idyllic settings of a landscape painting may hide the environmental devastation caused by deforestation and pollution. The social and environmental injustices of colonization and its impact on humans and non-human life as well as the matrixes of the land, soil, water and air can be explored through a socio-cultural, historical, environmental, and technological lens. Samantha Wilson states that Romantic poetry that often celebrates the beauty of nature, can be interpreted and explored through an ecocritical/ecopolitical lens; this critique and interpretive lens can enrich our understanding and appreciation. She suggests that feminist scholarship, biopoetics, radical landscape poetry, and experimental poetry, and critical race studies can cross “imaginative boundaries” to reveal “socio-environmental interdependencies” (p.3). Multimedia works, creative performances, and experimental projects can integrate different genres, forms, and disciplines….all with the aim of enriching and expanding insights into the complex interrelationship of humans and the nonhuman world. Wilson writes that “it is likely that ecopoetics will remain an overarching term for referring to consciously environmental writing and practice, albeit one which writers, critics, editors, and readers will continue to question, redefine, and transform” (Wilson, 2023).

We should have a land of sun,

Of gorgeous sun,

And a land of fragrant water

Where the twilight is a soft bandanna handkerchief

Of rose and gold,

And not this land

Where life is cold.

We should have a land of trees,

Of tall thick trees,

Bowed down with chattering parrots

Brilliant as the day,

And not this land where birds are gray.

Ah, we should have a land of joy,

Of love and joy and wine and song,

And not this land where joy is wrong.

To read more poems by Langston Hughes, please refer to the Internet Archive

To read Langston Hughes’ autobiography, The Big Sea (1940), please open the Project Gutenberg link here.

“An Earth Song” by Langston Hughes

It’s a spring song,—

And I’ve been waiting long for a spring song.

Strong as the shoots of a new plant

Strong as the bursting of new buds

Strong as the coming of the first child from its mother’s womb.

It’s an earth song,

A body song,

A spring song,

I have been waiting long for this spring song.

“I Have a Rendezvous with Life” by Countee Cullen

I have a rendezvous with Life,

In days I hope will come,

Ere youth has sped, and strength of mind,

Ere voices sweet grow dumb.

I have a rendezvous with Life,

When Spring’s first heralds hum.

Sure some would cry it’s better far

To crown their days with sleep

Than face the road, the wind and rain,

To heed the calling deep.

Though wet nor blow nor space I fear,

Yet fear I deeply, too,

Lest Death should meet and claim me ere

I keep Life’s rendezvous.

Additional Resources

Research the biohistory of the landscape depicted in a painting. Find two-three century landscape painings and explore the biohistory of the particular region. When was the landscape painted? What was going on in this part of the world at the time? As you view some of art images keep in mind the way the land has been used and the way that the geographic landscapes have changed over millennia. Compare and contrast the landscape and the way it has changed over time. For more learning resources about Indigenous art, please access the link below:

First Nations and Indigenous Art Selected Books

Winnipeg Art Gallery-Indigenous Art Resources

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Tate Britain: Landscapes Across the Centuries

Chicago Art Institute: Van Gogh and the Avant Garde: Modern Landscapes

Chicago Art Institute: 20th century landscapes

“Remember” by Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

The days of bondage—

And remembering—

Do not stand still.

Go to the highest hill

And look down upon the town

Where you are yet a slave.

Look down upon any town in Carolina

Or any town in Maine, for that matter,

Or Africa, your homeland—

And you will see what I mean for you to see—The white hand;

The thieving hand.

The white face;

The lying face.

The white power:

The unscrupulous power

That makes of you

The hungry wretched thing you are today.

Brooklyn Museum Notes: Hip Ornament with Human Face

“Benin court officials have long worn a variety of brass ornaments as part of their elaborate regalia for ceremonial occasions. Such ornaments were worn on the left hip, covering the closure of a wrapped skirt. The three metal scarification marks on either side of the forehead identify the individual portrayed as a royal Edo man. Similar items of regalia are worn by Benin court officials today”

“Heritage” by Countee Cullen (For Harold Jackman)

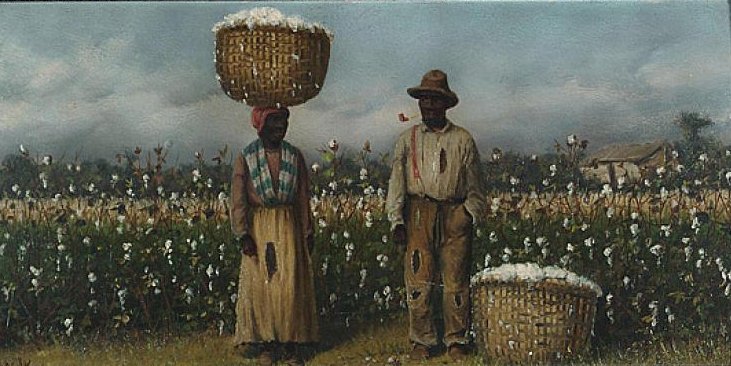

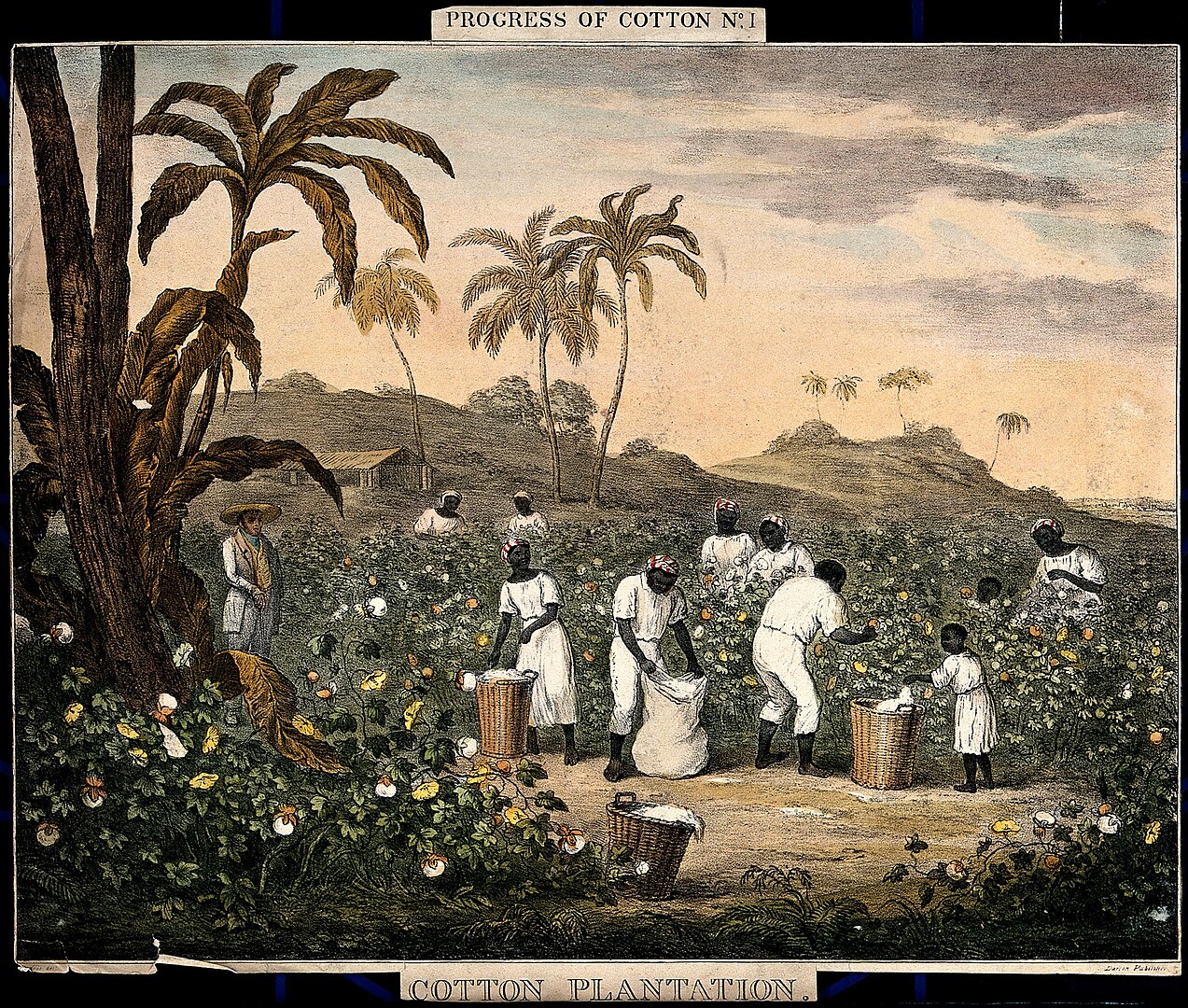

[Homer] revisited the South in the mid-1870’s to witness the change, or rather the absence of it, that Reconstruction had brought to the lives of former slaves. The result was a work like “The Cotton Pickers.” Stately, silent and with barely a flicker of sadness on their faces, the two black women in the painting are unmistakable in their disillusionment: they picked cotton before the war and they are still picking cotton afterward.

Note about Homer’s Painting “The Cotton Pickers”:

“Slave holding ideologies that had been embedded in colonial and metropolitan laws in the south for centuries were difficult to dismantle. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation, life was brutally oppressive for many African Americans after the so-called “Reconstruction.” While the women’s baskets are full of cotton, their work seems unending given the vast expanse of the fields. One art critic wrote that despite their bondage, “ the women give the impression of looking forward with thoughtfulness and determination. They stand erect, emanating the force of will to handle their difficult circumstances. In painting the background, Homer may even offer a promise of a better future. From left to right, the horizon progresses from a single tree to a forest, which might be interpreted as ‘one hope turning into a unified force of change.” the women give the impression of looking forward with thoughtfulness and determination. They stand erect, emanating the force of will to handle their difficult circumstances. In painting the background, Homer may even offer the promise of a better future. From left to right, the horizon progresses from a single tree to a forest, which might be interpreted as “one hope turning into a unified force of change.”

Additional Resources

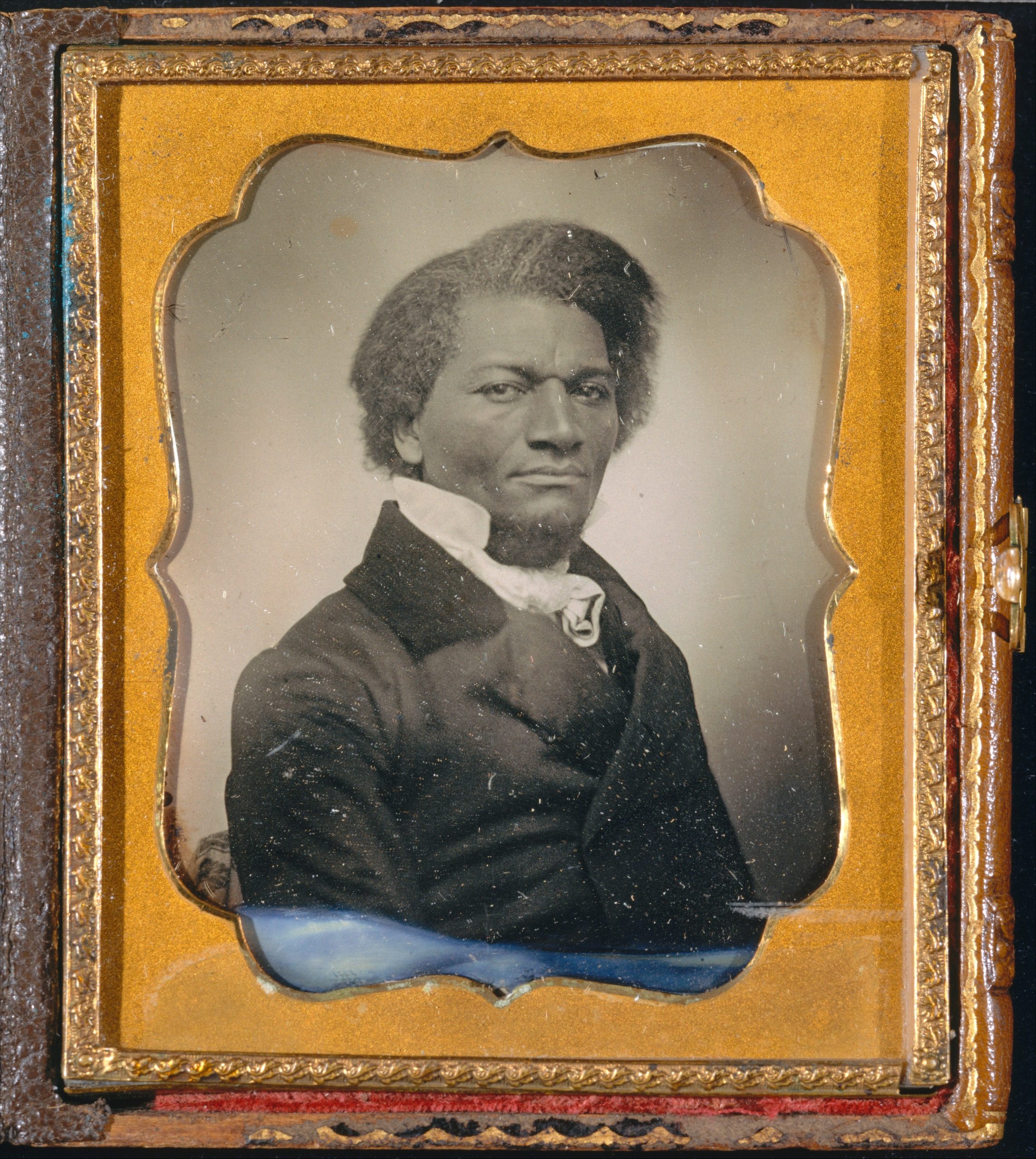

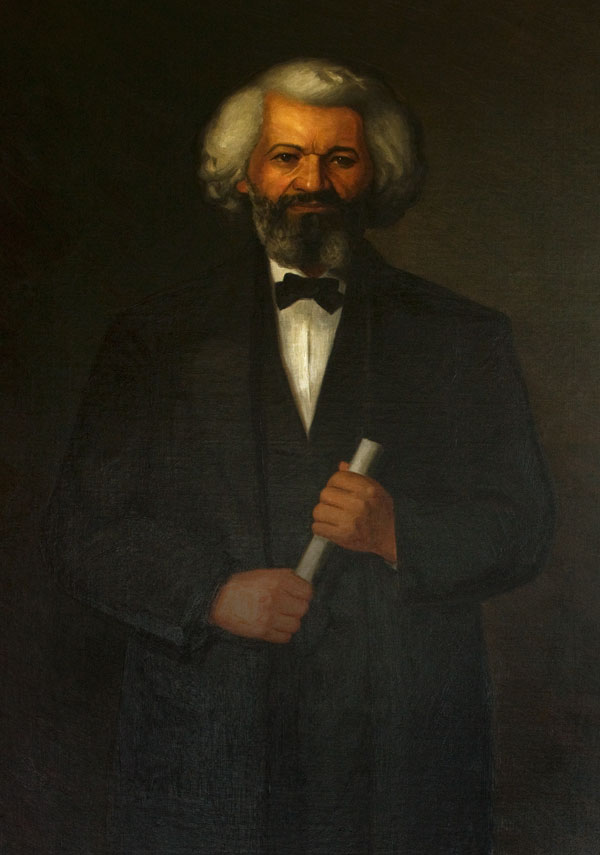

Eyre Crowe’s (1824-1910) painting depicting enslaved African Americans “waiting for sale” can be explored from a cultural, historical, and social perspective with literary studies of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye or Beloved. Contemporary books such as Ibram X Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning, the 1619 Project: A New Origin Story by Nikole Hannah -Jones (2021) and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste are powerful non-fiction texts that address the themes of racism and the intergenerational trauma and aftermath of slavery. Cornell West’s (2015) compilation of speeches and memoir excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr. can be examined from a new light in 2023. King’s prophetic words take on a new meaning and urgency in the light of ongoing racial and social struggles for equity and human rights. Photographs and visual art present powerful non-written images that can be a catalyst for creative inquiry. These texts can also be used within a larger study of the Black Lives Movement today. Newer texts such as West’s ( The Radical King (2015, Penguin Random House), Ta Ne-hesis Coates’ Between the world and me, David W. Blight’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom ( 2018, Simon and Shuster), Tya Miles All that She Carried (2021, and Esi Edugyan’s (2021)Out of the are rich sources of non-fiction that analyze the historical and cultural roots of slavery as well as the growing movement toward human rights and freedoms What has changed? What continues to stay the same? How do we re-activate the vision that great transformative leaders like Frederick Douglass or MLK had? Learning stations, cultural, historical, and social research, essential questions, and juxtaposing visual images with poetry, narratives, and other literary and non-fiction works have the potential to re-image literacy learning from a multi-modal lens.Books like Esi Edugyan’s (2021) Out of the Sun highlight the importance of considering stories and narratives that are at the margins. She suggests that it is important to bring these stories into centrality. It is important to appreciate “overlooked narratives” (p. 3). Edugyan’s “part memoir, part travelogue, and part history” centres around African stories with a context of critical race perspectives, Edugyan’s message has wide-ranging applications (Magro and Sfeir, 2023). She writes:We speak so much about the ‘universality’ of being human, about the similar things that connect us. I don’t want to lose sight of that. But in some ways, such talk camouflages the problem of difference—not difference itself, but our diminishment of it. It can be just as illuminating, I think, to look at the opposite. This year of lockdowns, and sickness has starkly revealed the gulfs between our lives. Experiences divide us, uneven access to necessities and comforts, different childhoods, traumas, faiths. If we wish to understand each other, we must first acknowledge the vastly unequal places from which we each speak, the ways some have been denied voices when others are so easily heard. (Edugyan, 2021, p.2)Edugyan analyzes art history, memoir, and narrative from a critical race perspective. She examines “the visual manifestations of an idea of Blackness, an idea informed by slavery” (Edugyan, 2021, p. 13). The Atlantic slave trade lasted for nearly four hundred years and more than twelve million people left sub-Saharan African destined to be enslaved to forced labour in the colonies (Edugyan, 2021). The portraiture of Blackness was tied to an imagined conception of Black people:To have a portrait painted was…an expression of power. And in these portraits, Black servants are often shown staring adoringly up at their masters, their heads wound in coloured turbans and wearing robes whose brightness makes an obvious contrast against the more sober and elegant clothes of their better….In his extravagant dress, a Black pageboy became the literal embodiment of his master’s riches, his servitude sometimes made clear by a silver ring in his ear or a silver collar around his neck. Black musicians and court performers also served to express this wealth. They are fantasies of slave life, implying a satisfaction with one’s lowly role and the implicit superiority of the master or mistress whose dignified bearing cannot help but inspire deference. The images glorified a world so far divorced from the penury of plantation labour, from the brutalities of the transatlantic voyage, that the gulf is astonishing. (Edugyan, 2021, p.15).Edugyan’s (2021) reflections about critical art studies can provide an excellent foundation for educators who wish to encourage literacy learning from a social, cultural, and historical lens. Students can research the historical and cultural background of the artist and the subjects/landscapes painted. How are people situated in the painting? How truthful or dishonest is the particular painting in portraying life worlds? How have things changed? How have they remained the same? Where is the setting? When was the artwork painted? What was going on in the world (specific country, city, town) at the given time? What can we learn about the culture and society (specific to the painting) at the time? From the details provided what can we assess about their age, background, social class, and so on? What is going on in the painting When was the piece created? How influential was the artist? What did the artist hope to achieve? What message do you think the painter wishes to covey about the people, landscapes, animals, world view, and so on?

Metropolitan Museum Art Notes:“This bust is perhaps the most well-known nineteenth-century sculpture of an enslaved Black figure. A virtuosic display of artistic achievement, the composition was modeled after an unidentified woman whose features Carpeaux recorded in exquisite detail. Yet this bust is not a portrait. Rather, it depicts the Black figure as an enslaved and racialized “type.” Created twenty years after the abolition of slavery in the French colonies (1848), the sculpture was debuted in[1] Paris in 1869 under the title Négresse, a term that reinforces the fallacy of human difference based on skin color. The subject’s resisting pose, defiant expression, and accompanying inscription – “Pourquoi Naître Esclave!” (Why Born Enslaved!) – convey an antislavery message. However, the bust also perpetuates a Western tradition of representation that long saw the Black figure as inseparable from the ropes and chains of enslavement. The present bust is one of only two known versions carved in marble.”To read more about this work of art and others, please open the Metropolitan Museum of Art link here.

Metropolitan Museum Note on Little Ida Image: “In a 1908 interview Calverly recalled the subject of this naturalistic relief and the circumstances of its production. He met Ida at a summer hotel while she tended a boy whose portrait he was modeling, and noticed the “string of alabaster beads around her long neck, and large red ear-drops.” Calverley included anecdotal touches in this portrait, including the curls of hair escaping from her knotted scarf, the unbuttoned collar, and the slight twist of the necklace. A prominent portraitist in Reconstruction-era New York, Calverley also produced likenesses of Abraham Lincoln and the radical abolitionist John Brown. In 1899 he revised Ida’s portrait to include the inscription “The Race John Brown Died For,” a testament to Brown’s legacy.”

Note about Juan de Pareja: Enslaved as a studio assistant to Diego Velasquez for nearly 20 years, de Pareja became an artist in his own right after his emancipation. To read more about his life and art please open the link here.

“Velázquez most likely executed this portrait of his enslaved assistant in Rome during the early months of 1650. According to one of the artist’s biographers, when this landmark of western portraiture was first put on display it “received such universal acclaim that in the opinion of all the painters of different nations everything else seemed like painting but this alone like truth.” Months after depicting his sitter in such a proud and confident way, Velázquez signed a contract of manumission that would liberate him from bondage in 1654. From that point forward, Juan de Pareja worked as an independent painter in Madrid, producing portraits and large-scale religious subjects.”

“Painted at a time of rapidly expanding British colonialism, this is an exceptionally rare independent likeness of an identifiable Indian woman by an eighteenth-century English artist. As identified by her portrait’s inscription, Joanna de Silva was a native of Bengal, in eastern India, and was employed as a nursemaid in the family of an officer with the British East India Company. She later accompanied an orphaned daughter of the family to England, where she sat for this portrait. The sitter wears the delicate Indian textiles that were sought after around the globe in the 1700s.”

Edward Mitchell Bannister

Ira Aldridge (1807-1867), “Ira Frederick Aldridge (July 24, 1807 – August 7, 1867) was an American-born British actor, playwright, and theatre manager, known for his portrayal of Shakespearean characters. James Hewlett and Aldridge are regarded as the first Black American tragedians.“Born in New York City, Aldridge’s first professional acting experience was in the early 1820s with the African Grove Theatre troupe. Facing discrimination in America, he left in 1824 for England and made his debut at London’s Royal Coburg Theatre. As his career grew, his performances of Shakespeare’s classics eventually met with critical acclaim and he subsequently became the manager of Coventry’s Theatre Royal. From 1852, Aldridge regularly toured much of Continental Europe and received top honours from several heads of state. He died suddenly while on tour in Poland and is buried in Łódź. Aldridge is the only actor of African-American descent honoured with a bronze plaque at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. Two of Aldridge’s daughters became professional opera singers.” (Wikipedia).

“Harlem” (A dream deferred) by Langston Hughes

To read more poems by Langston Hughes, please open the link here.

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895): Lessons of the Hour (Excerpt). Douglass’s speech speaks to the unresolved racial conflicts of our time:

The presence of eight millions of people in any section of this country constituting an aggrieved class, smarting under terrible wrongs, denied the exercise of the commonest rights of humanity, and regarded by the ruling class in that section, as outside of the government, outside of the law, and outside of society ; having nothing in common with the people with whom they live, the sport of mob violence and murder is not only a disgrace and scandal to that particular section but a menace to the peace and security of the people of the whole country I have waited patiently but anxiously to see the end of the epidemic of mob law and persecution now prevailing at the South. But the indications are not hopeful, great and terrible as have been its ravages in the past, it now seems to be increasing not only in the number of its victims, but in its frantic rage and savage extravagance. Lawless vengeance is beginning to be visited upon white men as well as black. Our newspapers are daily disfigured by its ghastly horrors. It is no longer local, but national; no longer confined to the South, but has invaded the North. The contagion is spreading, extending and over-leaping geographical lines and state boundaries, and if permitted to go on it threatens to destroy all respect for law and order not only in the South, but in all parts of our country — North as well as South. For certain it is, that crime allowed to go on unresisted and unarrested will breed crime. When the poison of anarchy is once in the air, like the pestilence that walketh in the darkness, the winds of heaven will take it up and favor its diffusion. (Frederick Douglass, 1894, Lessons of the Hour)

Connecting with Contemporary Texts: Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

In his bestselling book Between the world and me, Ta-Nehisi Coates (2015) describes the way in which internalized and systemic racism prevents African American children, youth, and adults from achieving their dreams and goals. He describes the systemic barriers that he faced as a youth and adult and his determination to succeed and excel amid adversity. The narrative of America is haunted with racism. Coates writes his narrative in the form of a letter to his fifteen year old son. Coates describes the harm and hatred of racism a “visceral experience” that “dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, and breaks teeth”(p.10). While he cautions his son not to look away from the violent truth, he also encourages hope, perseverance, and the importance of valuing and cherishing his own life. Racial profiling and racism continue and Coates cautions his son not to internalize hatred and violence. In the following paragraph, Coates describes what it is to be Black in the Baltimore of his youth: To be black in the Baltimore of my youth was to be naked before the elements of the world, before all the guns, fists, knives, crack, rape, and disease. The nakedness is not an error, nor pathology. The nakedness is the correct and intended result of policy, the predictable upshot of people forced to live under fear. The law did not protect us. And now, in your time, the law has become an excuse for stopping and frisking you, which is to say, for furthering the assault on your body. But a society that protects some people through a safety net of schools, government-backed home loans, and ancestral wealth but can only protect you with the club of criminal justice has either failed at enforcing its good intentions or has succeeded at something darker. (Coates, 2015, pp. 17-18). Coates highlights the systemic barriers through the educational and work systems that in one way or another, erode confidence, potential, and possibility. Surviving in the tough neighbouring where the streets laws were “amoral and practical” meant learning new skills and “another language” that was not taught in the traditional schools. Coates describes feeling alienated at school; his dreams, hopes, and experiences were not validated and “the laws of the schools were aimed at something distant and vague” (p. 25). He describes the incongruity between the reality of his youth and the expectations for success at school. It was as if there were two distinct “galaxies” that had a diametrically different set of rules, dreams, expectations, and ideals. “Schools did not reveal truths, they concealed them” (p. 27). Throughout his memoir/letter to his son, Coates recounts his search for meaning and identity that took him to visit Dr. Mabel Jones, the mother of his slain gifted college friend Prince Jones. Rather than addressing the injustice of 25 year old Prince Jones’s slaying by a police officer, the tragic circumstances of his killing had been erased by American society. Coates emphasizes that the social structures reinforce the illusion of a dream that there is equal justice under the law: [Dr. Jones] could not lean on her country for help. When it came to her son, Dr. Jones’s country did what it does best—it forgot him. The forgetting is habit, is yet another necessary component of the Dream. They have forgotten the scale of theft that enriched them in slavery; the terror that allowed then, for a century to pilfer the vote; the segregationist policy that gave them their suburbs. They have forgotten, because to remember would tumble them out of the beautiful Dream and force the to live down here with us, down here in the world. (Coates, 2015, p. 143).In his travels to Paris, Coates journeys from feeling “landless and disconnected” to points of awareness, insight, confidence, and transformation. Coates’ narrative can be explored further with interviews/presentations. Poems and art images can also complement passages in his book. Coates’ memoir style can be dramatized in individual and choral readings. Students can compare Coates’ experiences with their own. Related texts by authors Phillis Wheatley, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Ralph Ellison, Maya Angelou, Isabel Wilkerson, and Alice Walker can also be explored from a psychological, philosophical, socio-cultural and racial lens.

In exploring the historical account of the famous painting of Elizabeth Dido and her cousin by John Martin, Edugyan notes the power dynamic of the two girls. Dido was the illegitimate daughter of a African slave captured from a Spanish ship in the West Indies by Admiral John Lindsay. The history records that after the death of her mother, Dido was sent to live in England “to be raised by Lindsay’s uncle Lord Mansfield’s home in a manner befitting their rant.” Lady Elizabeth (also featured in the front of the painting) also lost her mother and the two girls grew up together but had different experiences due to their race and background. By many accounts, Lord Mansfield loved Dido and yet according to Edugyan, Dido’s experiences were murky at best; she was “not quite sister, not quite servant” (Edugyan, p. 15). The power differential between the two girls is noted by Edugyan. Lady. Edugyan notes:In Martin’s portrait, I saw an emphasis on Dido’s subordination—her positioning, in the background, her service bowl. She seemed fixed in the tradition of lady’s maids, footmen, and slaves, and reflected the same contentious visions we’ve always had of such figures. But as I came to know more of her life circumstances, I understood that on some level what her image also represented, beyond her physicality, was the sometimes obscuring nature of visibility itself. Here was a woman who, though uneasily, moved through aristocratic England in an era that some even today insist on viewing as culturally homogenous…Dido’s portrait dredges up questions of how human migration, both forced and chosen, has shaped the West for centuries. In [Dido Elizabeth’s] inescapable gaze she seems to say, we have always been here. (p.18).Edugyan(2021) refers to the contemporary African American artist Kehinde Wiley (1977-) whose famous portrait of Barack Obama amid a background of flowers hangs in the Smithsonian Art Museum in Washington, DC. (please open the link here to view K. Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama). Wiley repositions African people in a familiar classic poses from well-known paintings by the “Old Masters” For example in Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) by Jean-Louis David (1748-1825), Wiley recreates the painting with an anonymous Black man in place of Napoleon as the central figure. Wiley’s paintings challenge and provoke critical reflection about the art, power, position, privilege, class, and race. His paintings reflect a beauty, power, and humanity that had been eroded throughout the centuries of slavery. In his paintings Wiley challenges the “social hierarchies, hatreds and divisions”; through his art Wiley challenges Western assumptions and works toward dramatic transformation. Edugyan writes:Passing wall after wall of Wiley’s work, I couldn’t shake my sense that in every Black and brown face, in the grandeur of every expression and every pose that evoked Velázquez, Gauguin, Caravaggio, what I was really seeing was a plea to have an essential humanity acknowledged. The vivid physicality of his subjects, their skin so lovingly burnished and glowing with health, asked us to consider the source of that vitality, the beating heart, the thrumming blood. These were joyful, furious, anxious, lustful, jealous, terrified generous people. Their humanity was without refutation. The ripped jeans, the T-shirts of these divine figures might be the clothes of Akai Gurley, of Michael Brown, of a beloved uncle or son. They might, in our day, be those of George Floyd. What can deified can also be killed; what can be celebrated can also be toppled. Our social hierarchies, our hatred and divisions, are constructs awaiting dismantlement. This is the Western world as we have built it. Wiley seems to say, and it can be changed. (Edugyan, 2021,p. 31).Each painting of Wiley tells a complex narrative that challenges viewers to re-vision prior assumptions and grand narratives of history; we need to find the “unearthed threads” to weave a new narrative rooted in social justice and life affirming values. “Artists are here to record the stories of our hearts, not our political stories, but rather our interior stories so we’re apolitical” (Kehinde Wiley in Edugyan, p. 36).For more information about Kehinde Wiley, please read the following articles here and here.

The Art of Kehinde Wiley

Additional Resources

Resources African Art and Poetry from The Harlem Renaissance:

- For more poetry by Maya Angelou, please open the link here.

- Enter your footnote content here. ↵