12.3 Expressions of a Floating World: The Ukiyo-e Artistic Style and Selected Japanese Poetry

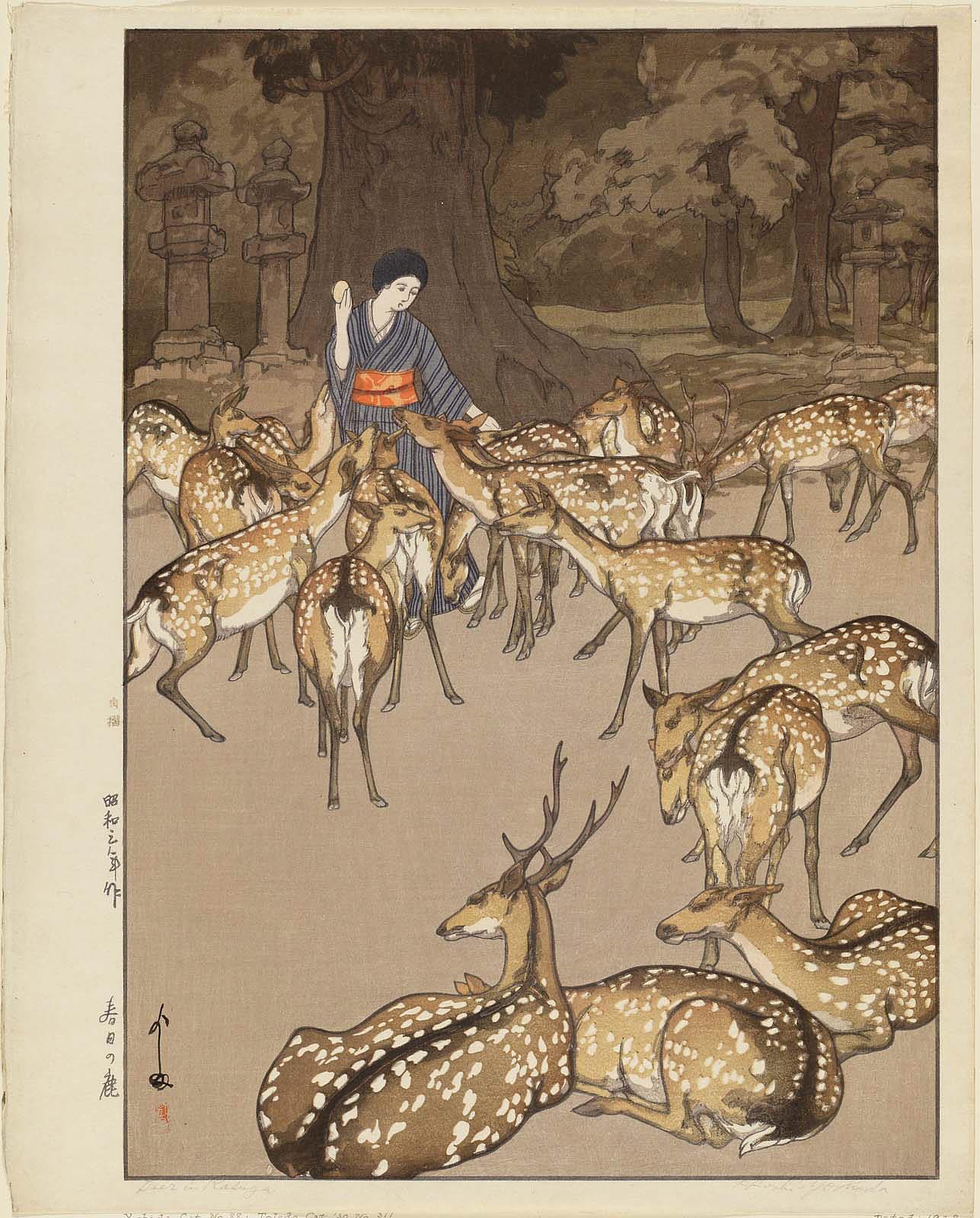

“The stars indeed” by Matsuo Bashō

The stars indeed

lay out their blanket

of spotted fur.

*Bashō (1644-1694) was a celebrated Japanese Haiku poet. To read more of his poetry, please open the link here and here.

“The wind in the rice leaves” by Morotada

The wind in the rice leaves

Wakes me at midnight;

I listen to the distant cry of the deer

In the mountain village. (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1963, p.120).

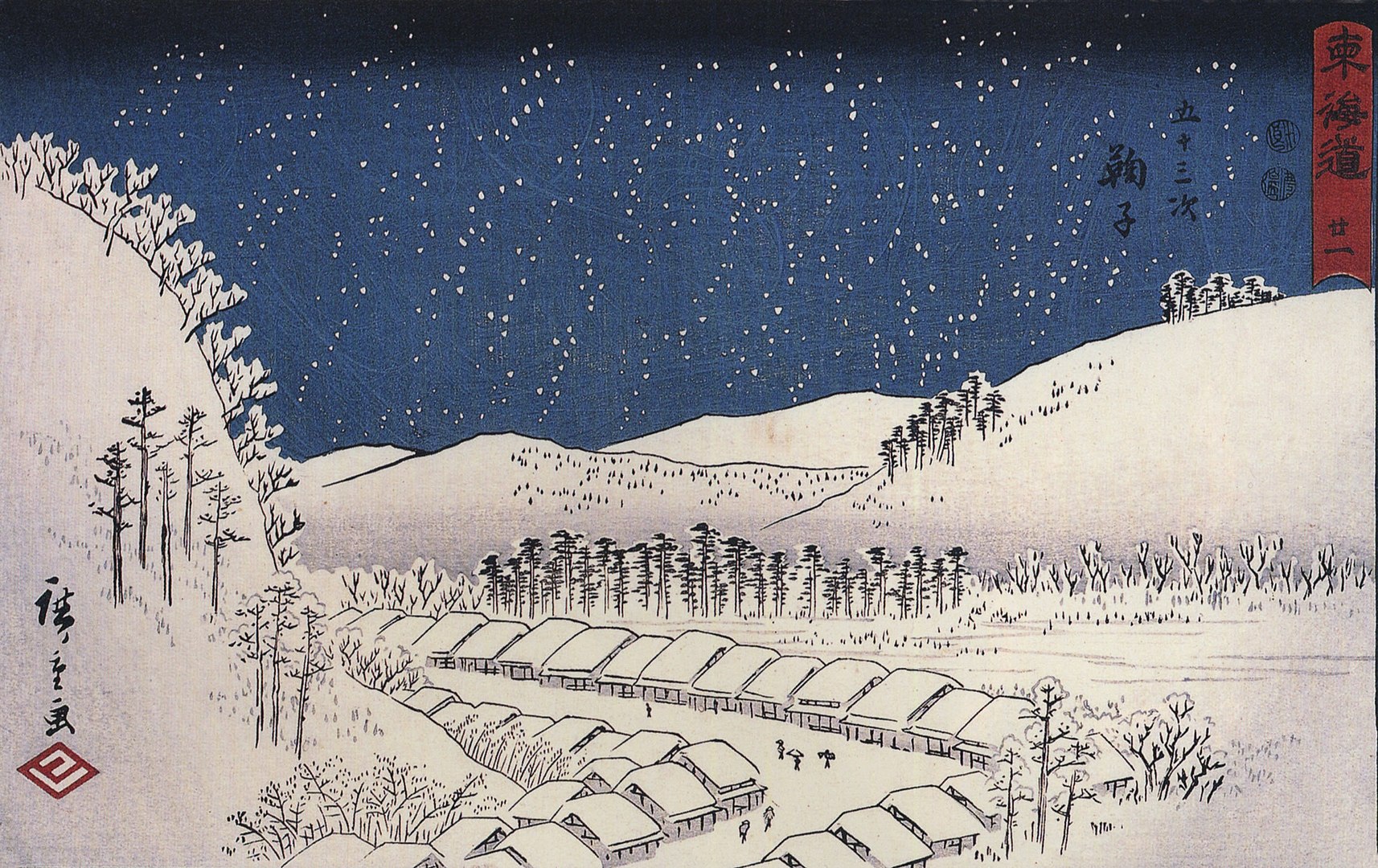

Ukiyo-e Woodblock Print Images and Selected Poetry and Verse

In Japanese culture, art and poetry often coincide and complement each other. In this section, art images from the Ukiyo-e style of woodblock printing are presented with varied Japanese poems that include Haiku and Waka or Tanka. Resources for further research and inquiry into the Ukiyo-e artistic style are provided. Lessons for teaching Haiku poetry are included in this section as well. The themes of nature that emerge from viewing and reading this section would further complement other nature-themed chapters in this volume. A majority of English translations of the Japanese poetry featured in this chapter are now in the Public Domain (PD). The notable translators include Yonejirō Noguchi (1875-1947), Clay MacCauley ( 1843-1925), and Reginald Horace (R.H.) Blyth. (1843-1925). Their translations encouraged interdisciplinary thinking and transcultural understandings.

Key Takeaways

- The Ukiyo-e style of vibrantly detailed Japanese woodblock prints emerged during the Edo period of Japan from 1657-1867. This time frame represented a golden age of flourishing in Japanese arts. During this time, the Ukiyo-e School of woodblock printing represented a new creative and artistic freedom. The ukiyo-e prints were viewed as a mirror and lens of Japanese life. During the Edo period (also called Tokugawa period) the shogunate or a military dictatorship (founded by Tokugawa Leyasu) held the executive power and controlled Japan. Society was highly stratified and outside travel to other countries was forbidden. Despite many limits, this was a time of relative internal peace, economic growth, and political stability in Japan. In contrast to the rigid political dictatorship, alternative cultural spaces that included tea houses, literary and artistic meeting places, Kabuki theatre, parks, gardens, street festivals, and regattas on the river emerged. Each day held the promise of enjoyment. (Cawthorne, 2005).

- Sean McManamon (2016) explains that the Ukiyo-e woodblock prints provide an important narrative informing the dynamic socio-economic, political, and cultural changes that were occurring in Japanese society throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Just as Renaissance paintings have been used to explain concepts and ideas of humanism, so too can ukiyo-e print can help learners visualize concepts about pre-modern Japanese society. These narratives stood in contrast to the stereotyped images of “dashing Samurai and the passive merchants and peasants.” (McManamon, 2016, p.444). The Ukiyo-e prints reflected a more nuanced and complex view of the political, social, and cultural life in Japan during that time. Growing urbanization, the move away from a feudal society, and the rising power of the merchant classes gave rise to new expressions and freedoms. McManamon highlights the value of using Ukiyo-e prints in the classroom as a way to help students understand the era of pre-modern Japan:

- “Throughout the years, students have responded positively to Japanese woodblock prints. They are very student friendly in that they are visual and appeal to people of many ages; are not abstract and can be appreciated on many levels; and are abundantly accessible in books and on the Internet. Students also respond positively to ukiyo-e due to their great variety: samurai, geisha, actors, and landscapes. Young people can easily pick up the themes of bravery, humor, satire, and beauty. Ukiyo-e have been used for decades to vividly illustrate books and other literature on

pre-modern Japan.” (McManamon, 2016, p. 444).

- “Throughout the years, students have responded positively to Japanese woodblock prints. They are very student friendly in that they are visual and appeal to people of many ages; are not abstract and can be appreciated on many levels; and are abundantly accessible in books and on the Internet. Students also respond positively to ukiyo-e due to their great variety: samurai, geisha, actors, and landscapes. Young people can easily pick up the themes of bravery, humor, satire, and beauty. Ukiyo-e have been used for decades to vividly illustrate books and other literature on

- It is important to note that the term “ukiyo-e” is open to different interpretations. In Asai Ryōi ‘s (1661) Tales of the floating world, Ukiyo-e could also be associated with sadness, sorrow, weariness, and nostalgia in knowing that joy is only temporary. Ukiyo-e expressed the idea that life was ephemeral, fleeting, and mysterious. Asai Ryōi (1661) describes the essence of “ukiyo-e” as “living only for the moment, turning our full attention to the pleasures of the moon, the snow, the cherry-blossoms and the maple-leaves, singing songs, drinking wine, and diverting ourselves just in floating, floating…this is what we call ‘ukiyo’.”(Ryōi, 1661, Tales of the Floating World or. In his writing, Ryōi, differentiates between the Buddhist view of ukiyo and the Edo perspective of ukiyo-e. The lifestyle depicted in the Edo floating world is one of “carpe diem” or seizing the joy of each day as there is no guarantee of what the next day would hold. This epicurean philosophy contrasted with the Buddhist ‘ukiyo perspective that focused on spiritual commitment and devotion, potentially benefitting the individual in the next life.

- Additional Resources:

- .Brooklyn Museum of Art Ukiyo-e collection of Woodblock prints

- The Haiku Foundation.

- Lesson Plans: Ukiyo-e and Haiku: Thousand Word Project developed by Katherine Cargile Lewiston, 2023. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 2024. The Floating World of Ukiyo-e: Shadows, Dreams, and Substance

- Examples of Woodblock prints in the Ukiyo-e style can be found here.

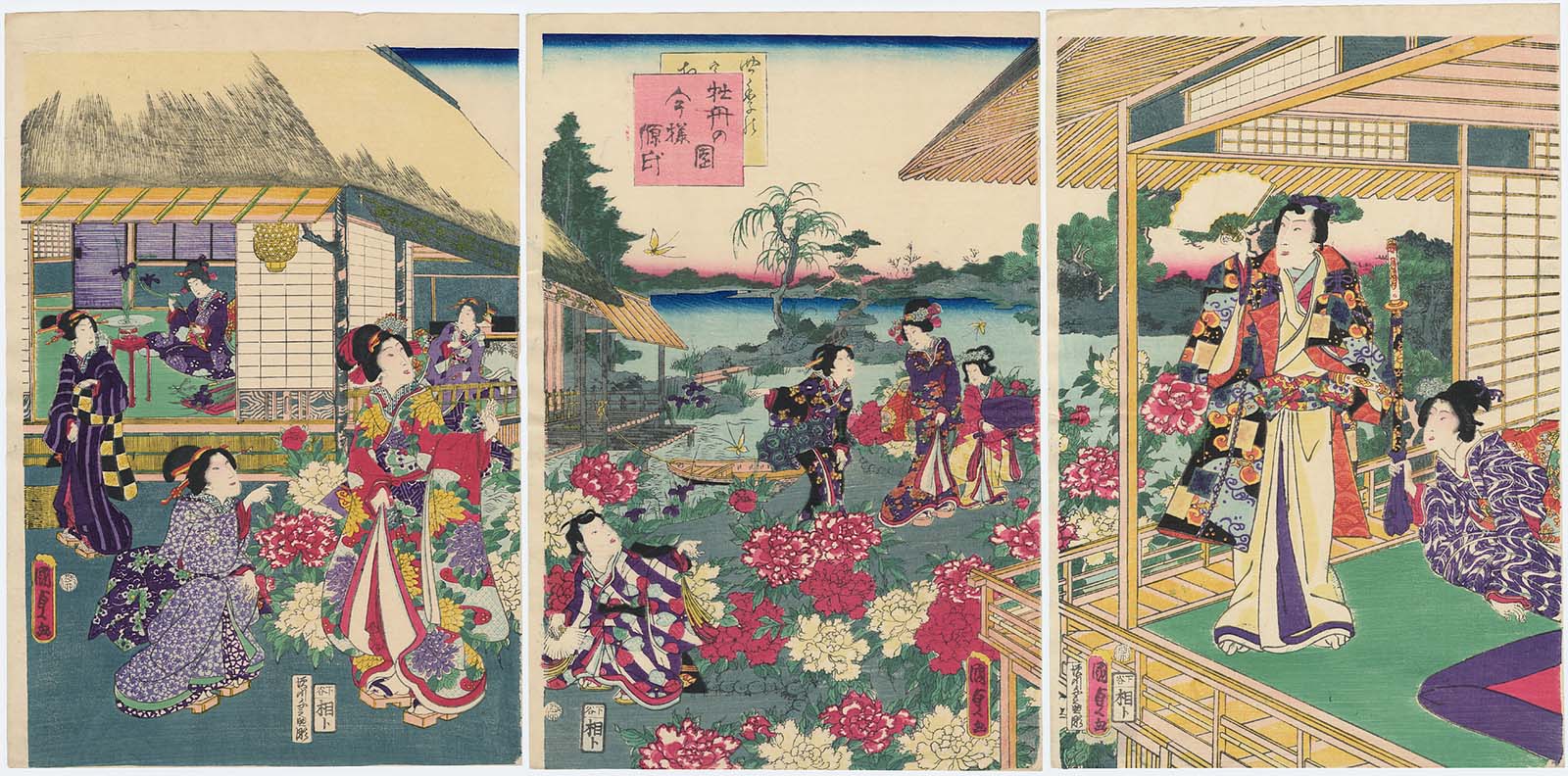

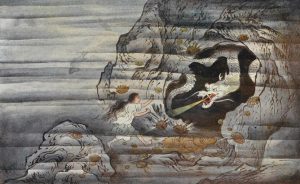

The ‘Tale of the Genji’ or Genji Monogatari, written in the 11th century CE by Murasaki Shikibu, a court lady, is Japan’s oldest novel and possibly the first novel in world literature. The classic of Japanese literature, the work describes the life and loves of Prince Genji and is noted for its rich characterisation and vivid descriptions of life in the Japanese imperial court. The work famously reproduces the line ‘the sadness of things’ over 1,000 times and has been tremendously influential on Japanese literature and thinking ever since it was written. The ‘Tale of Genji‘ continues to be retranslated into modern Japanese on a regular basis so that its grip on the nation’s imagination shows no sign of loosening. The work’s author is considered to be a lady of the imperial court by the name of Murasaki Shikibu who wrote it over several years and completed it around 1020 CE during the Heian period (794-1185 CE).”

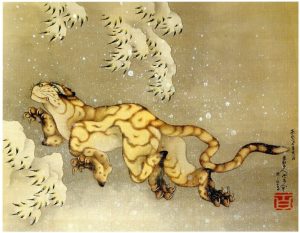

Courtesy: By Maruyama Ōkyo – scan by User:Fraxinus2, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18569703

If on Mount Inaba’s peak

I should hear the sound

Of the pine trees growing there,

Back at once I’ll make my way (Translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917).

Over the wintry

forest, winds howl in rage

with no leaves to blow.

Japanese Poems and Poets

The Hundred Poets Compilation:

The anthology Hyaku-ninisshu (One hundred poems by one hundred poets) includes 100 poems by 100 different poets. The poems were compiled by the thirteenth-century critic and poet Fujiwara no Sadaie (also known as Teika). The collection includes traditional Japanese poetry (waka and tanka) from the 8th century to the 13th century. The traditional “waka” poems are five lines long and are composed of 31 syllables (waka). A version Illustrated by the first Ukiyo-e artist Hishikawa Moronobu (1618-circa 1694) features 58 images of the poets or examples of scenes described in the poems.

To read some of the poems by Teika please open the link here.

Classical Japanese Literature.

For lessons on how to write haiku and tanka poems please open the creative writing exercise developed by Clare Stevens (2021) here.

Additional resources on writing tanka poems can be found here.

18th Century Scroll containing Waka poems of flowers and birds by Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1201), ( Handscroll: Ink and color on Paper. Dimensions: Image: 7 3/16 in. × 18 ft. 7 1/4 in. (18.3 × 567 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Public Domain. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/670941

Metropolitan Museum Art Note about Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241).

“One of the greatest literary arbiters of the classical to early medieval era, Fujiwara no Teika (also known as Sadaie, 1162–1241) was a critic, calligrapher, and diarist as well as an author of waka (31-syllable verse) poetry. He was appointed to the Kyoto court’s Bureau of Poetry in 1201, and enjoyed the patronage of Retired Emperor Gotoba (1180–1239). A prolific author, he produced numerous poems and literary commentaries, and was the primary compiler of the eighth imperially-commissioned anthology of poetry, “New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poetry” (Shinkokin wakashū, circa 1205). His literary achievements exerted a strong influence on Japanese poetry even into modern times.

This handscroll contains waka by Teika dedicated to flowers and birds of the twelve months of the year. Each waka accompanies a delicate image replete with poetic and seasonal references, painted in a style derived from the traditional yamato-e (Japanese-style painting) mode of narrative illustration.” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City).

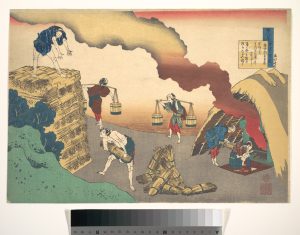

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), Image inspired by Gon-Gon-Chūnagon Sadaie (Teika) from the Series One hundred poems explained by the nurse. (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki). Woodblock print on paper. Edo Period (1615-1868). Dimensions: 10 1/4 x 15 in. (26 x 38.1 cm).Henry L. Phillips Collection, Bequest of Henry L. Phillips, 1939, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Public Domain. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/56157

“Waiting” by Gon-Chūnagon Sadaie ( also known as Teika, 1162–1241)

Waiting

for one who does not come

my passion burns

as the unceasing fires

beneath the salt-pans around

Matsuho Bay. (translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917).

Teika, one of Japan’s greatest poets and critics compiled the first collection of one hundred poems by one hundred poets.

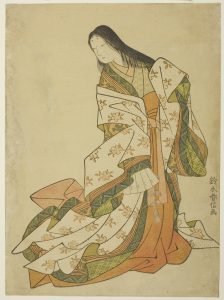

Suzuki Harunobu (1724-1770), By Suzuki Harunobu, The Poetess Ono no Komachi – Art Institute of Chicago [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75083683

Suzuki Harunobu (1724-1770), By Suzuki Harunobu, The Poetess Ono no Komachi – Art Institute of Chicago [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75083683

“Color of the flower” by Ono no Komachi

The color of the flower

Has already faded away,

While in idle thoughts

My life passes vainly by,

As I watch the long rains fall. (From, One Hundred Poets).

Additional Reference: Library of Congress, One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, 2023.

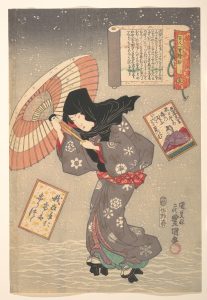

Utagawa Kunisada (Japanese, 1786–1864),Selected Scenes from One Poem Each by One Hundred Poets: Poem by Emperor Kōkō Woodblock Print, Ink and Colour on Paper, 19th Century, Edo Period, Japan (1615-1868). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Public Domain. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/73610

“For you” by Emperor Kōkō (830-887 AD). (Poem 15).

For you

I head out to spring fields

and gather first herbs,

while snow continues falling

upon my sleeves.

Courtesy: By Kitagawa Utamaro – Spice (archive), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56120278

Courtesy: By Kitagawa Utamaro – Yomiuri Shimbun, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56428939

If thou art to end, break now.

For, if yet I live,

All I do to hide ( my love)

May at last grow weak (and fail). (translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917).

Kabuki Theatre

The traditional form of Japanese Kabuki theatre is known for its all-male theatrical troupes, elaborate and colorful costumes, bold emotional expression, dramatic make-up ( kumadori make-up), ornate hair styles, and highly stylized dance/drama. The mixture of song, mime, dance, and drama centered on dramatic retellings and interpretations of traditional legends, morality tales, and historical events. In Kabuki, the actors may hold exaggerated and unorthodox facial and body pose to establish the personality of a character. Indeed, the word “kabuki” is often associated with bizarre, ornate, and avant- garde styles. Translated into English, the Japanese word kabuki consists of three characters: “Ka” (meaning song); “bu”(dance), and “ki” (skill). The popularity of Kabuki emerged throughout the 17th century and it reached its pinnacle in mid-18th century. The tradition of kabuki is often carried down from one generation to another so that male children might apprentice from their father to hone the skill and range of visual and vocal performances. Kabuki’s art founder Izumo no Okuni, formed a female dance troupe that performed dances and dramatic sketches in Kyoto; in 1629, women were banned from performing kabuki and all-male theatrical troupes became the norm. To read more about gender inclusivity and kabuki theatre, please open the links here and here.

In 2005 UNESCO declared kabuki theatre to be of exceptional universal value; it was described has having an “intangible heritage” ( for more information please open the link at Britannica).

Resources

To see more Kabuki in art please open the link here.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City: Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style.

Courtesy: Rogers Fund, 1914. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36654” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Allows us to break the flowering branches. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 70).

Courtesy: By Utagawa Kuniyoshi – http://visipix.com/search/search.php?userid=1616934267&q=%272aAuthors/K/Kuniyoshi%201797-1861%2C%20Utagawa%2C%20Japan%27&s=19&l=en&u=2&ub=1&k=1Copy of the print at Museum of Fine Art Boston, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=315242

Morning glory!

the well bucket-entangled,

I ask for water

Here I am among the flowers

I hear people laughing

In the spring mountains. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 71).

About the Poet Fukuda Chiyo-ni

“Fukuda Chiyo-ni (福田 千代尼, 1703 – 2 October 1775) or Kaga no Chiyo (加賀 千代女) was a Japanese poet of the Edo period and a Buddhist nun. She is widely regarded as one of the greatest poets of haiku (then called hokku). Some of Chiyo’s best works include The Morning Glory, Putting up my hair, and Again the women.

Being one of the few women haiku poets in pre-modern Japanese literature, Chiyo-ni has been seen an influential figure. Before her time, haiku by women were often dismissed and ignored. She began writing Haiku at seven and by age seventeen she had become very popular all over Japan and she continued writing throughout her life. Influenced by the renowned poet Matsuo Bashō but emerging and as independent figure with a unique voice in her own right, Chiyo-ni dedication toward her career not only paved a way for her career but it also opened a path for other women to follow. Chiyo-ni is known as a “forerunner, who played the role of encouraging international cultural exchange”. (Wikipedia)

Courtesy: By Utagawa Kunisada – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs divisionunder the digital ID jpd.02608.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2917849

Courtesy: By Isoda Koryūsai – http://diglib.princeton.edu/view?_xq=pageturner&_type=book&_doc=/mets/pudl0026.mets.xml&_inset=1&_filename=pudl0026/ga200801135/00000001.jpf&_start=1&_index=7&_count=6&6=1&div1=6, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82421622

To learn more about Hokusai’s Thirty Six Views of Mount Fuji please ope the links here and here.

Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York City:

To look at Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo please open the link here.

Courtesy: Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1985. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55919” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/xzh4n3bj is in the Public Domain.

Courtesy: By Toshikata Mizuno – http://free-artworks.gatag.net/tag/三十六佳撰, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60384333

Courtesy: By Yūsai Toshiaki – http://jp.japanese-finearts.com/item/list2/A1-91-151//Moon-at-Gojo-Bridge., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60394205

The Pillow Book (Makura no Sōshi ), AD 967 : A Source of Inspiration for Ukiyo-e Artists and Poets

Written over 1,000 years ago and highly original in style, Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book (994 A.D.)is considered a masterpiece of classical Japanese literature; with poetic style, Shonagon describes Japanese court life during the Heian period of old Japan. “Shōnagon described “the great mid-Heian period of feminine vernacular literature that produced not only the world’s first psychological novel, The Tale of Genji, but vast quantities of poetry and a series of diaries, mostly by Court ladies, which enable us to imagine what life was like for upper-class Japanese women a thousand years ago” (translation by Ivan Morris, Introduction, The Pillow Book, Penguin Classics, 1967). Sei Shonagon served as a lady-in-waiting at the Court of the Japanese Empress in the 11th century. Our understanding of her life is based primarily on her writings in The Pillow Book.

Sei Shōnagon wrote that her diaries and notebooks were filled with “odd facts, stories from the past, and all sorts of other things, often including the most trivial material. On the whole I concentrated on things and people that I found charming and splendid; my notes are also full of poems and observations on trees and plants, birds and insects.” (Shōnagon 994 A.D., The Pillow Book). Ukiyo-e artists were inspired by the writings of Sei Shōnagon and her contemporaries in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Seasons by Excerpt from The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon ( 966–1017 or 1025)

In Spring It Is the Dawn

In spring it is the dawn that is most beautiful. [1] As the light creeps over the hills, their outlines are dyed a faint red and wisps of purplish cloud trail over them.

In summer the nights. Not only when the moon shines, but on dark nights too, as the fireflies flit to and fro, and even when it rains, how beautiful it is!

In autumn the evenings, when the glittering sun sinks close to the edge of the hills and the crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos; more charming still is a file of wild geese, like specks in the distant sky. When the sun has set, one’s heart is moved by the sound of the wind and the hum of the insects.

In winter the early mornings. It is beautiful indeed when snow has fallen during the night, but splendid too when the ground is white with frost; or even when there is no snow or frost, but it is simply very cold and the attendants hurry from room to room stirring up the fires and bringing charcoal, how well this fits the season’s mood! But as noon approaches and the cold wears off, no one bothers to keep the braziers alight, and soon nothing remains but piles of white ashes.” (Sei Shōnagon, 967 A.D., The Pillow Book, Section One).

Art Images and Poetry of a Floating World: Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints and Haiku Poetry

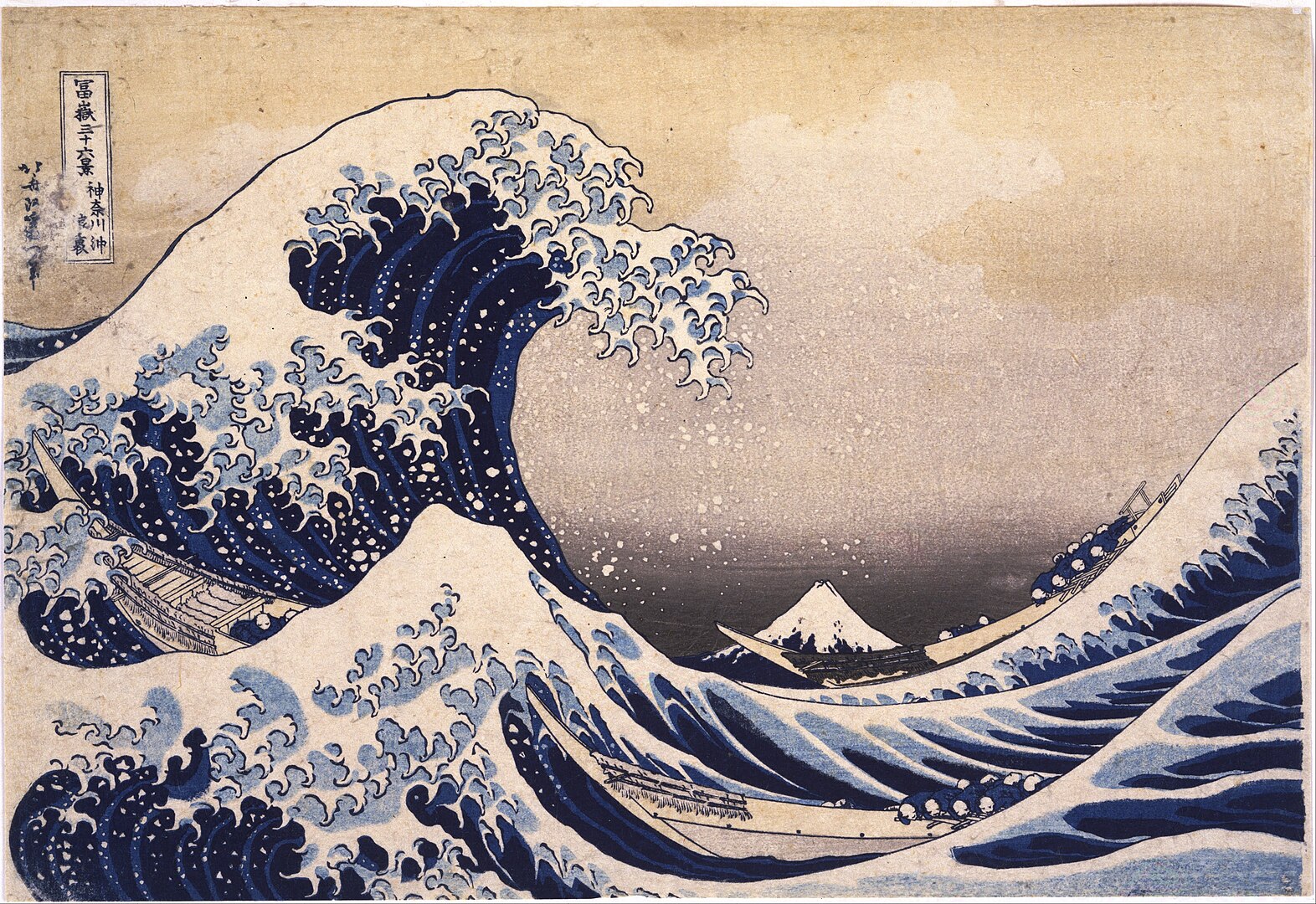

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), Rain Below the Mountain (from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji), Japan, Edo period (1615-1868). Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio. “https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1940.1002” by Cleveland Museum of Art is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾 北斎 (1760-1849):

“From the age of 6 I had a mania for drawing the shapes of things. When I was 50 I had published a universe of designs. But all I have done before the age of 70 is not worth bothering with. At 75 I’ll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish and insects. When I am 80 you will see real progress.

At 90 I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At 100, I shall be a marvelous artist. At 110, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before. To all of you who are going to live as long as I do, I promise to keep my word. I am writing this in my old age. I used to call myself Hokusai, but today I sign myself ‘The old man made about drawing.”

Note about the translator Clay MacCauley (1843-1925)

One of the best translations of Japanese poetry into English can be found in the 1917 anthology Single Songs of a Hundred Poets translated by Clay MacCauley (1843-1925), a veteran of the American Civil War. MacCauley studied theology at Princeton and later became a Unitarian minister. His work as an Unitarian minister enabled MacCauley to travel extensively; eventually, he was based in Japan. He continued his Unitarian missionary work and developed a fascination with the history, culture, and language of Japan. He became fluent in Japanese and one of his most influential books was Single Songs of a Hundred Poets; (Ogura Hyakunin Isshu from Hyakunin-Isshu). This book was published in Yokaham by Kelly & Walsh in 1917. The poems appear in both Japanese and English.

Katsushika Housai (1760-1849) began the last of his great print series when he was seventy-five. Peter Morse compiled eighty-nine of Hokusai’s prints in Hokusai: One hundred poets in 1989, Morse notes the richness of colour and the precision of detail that make Hokusai’s work exceptional. In addition to the poetry in Japanese verse, Peter Morse includes the English translations of poetry by 100 poets. Each poem is connected to a print by Hokusai. Morse uses MacCauley’s translations of the Japanese poems to complement Hokusai’s prints.

Source: Morse, P. (1989). Hokusai: One hundred poets. George Braziller, Inc., Publishers.

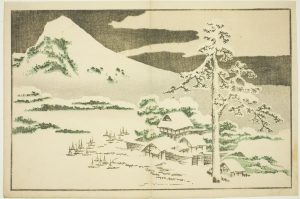

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), Mount Fugi in Winter (1809-1819), Color Woodblock Print. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. Frederick W. Gookin Collection. Public Domain. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/33412/mount-fuji-in-winter-from-the-picture-book-of-realistic-paintings-of-hokusai-hokusai-shashin-gafu

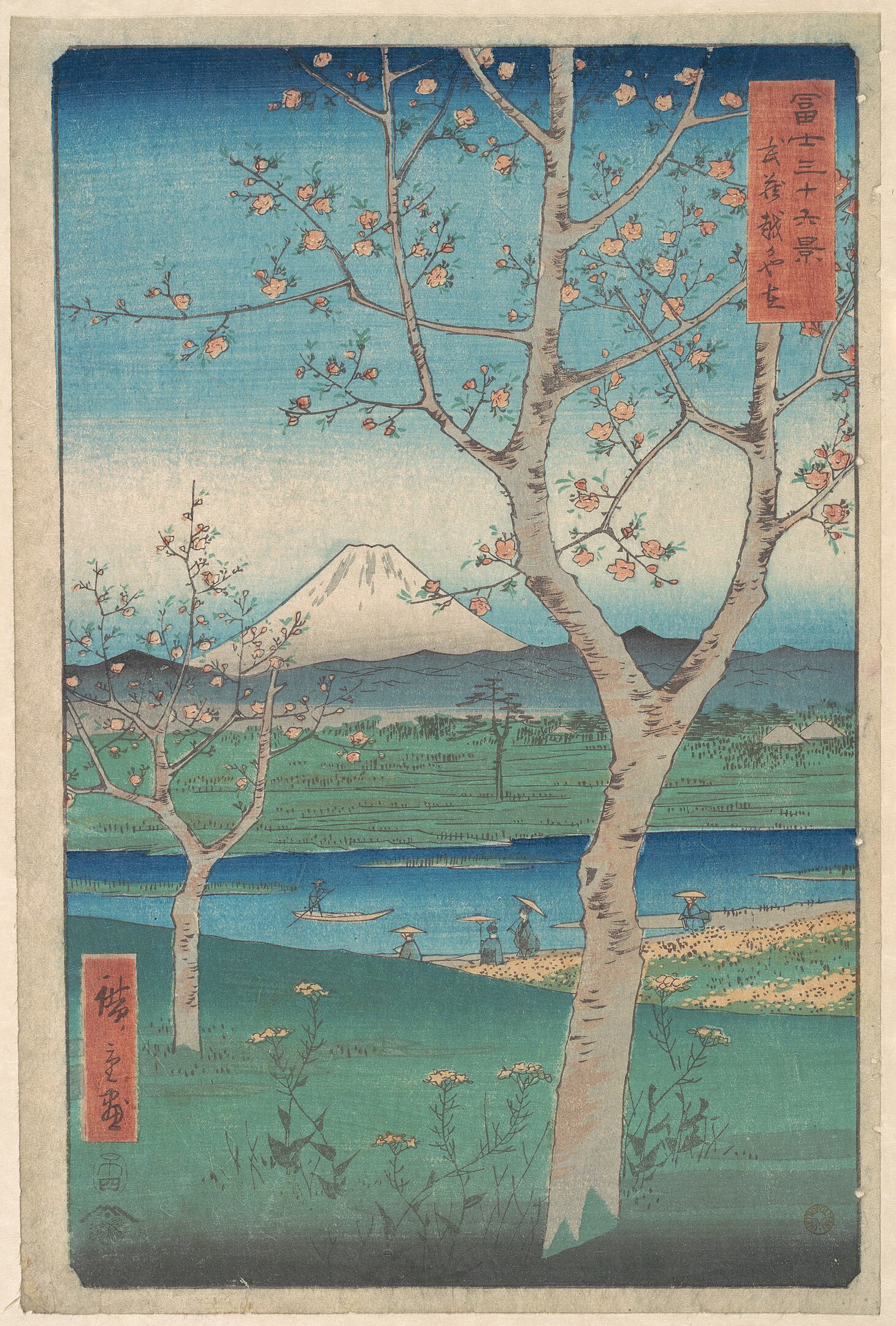

“When to Tago’s coast” by Yamabe no Akahito

When to Tago’s coast

I the way have gone, and see

Perfect whiteness laid

On Mount Fuji’s lofty peak

By the drift of falling snow. (Translation by Clay MacCauley)

“How Admirable” by Matsuo Bashō

How admirable!

To see lighting and not think

Life is fleeting. (Trans. by Robert Hass (1941-_ ).

From: J. Patrick Lewis (2015). Book of Nature Poetry. National Geographic Society (p. 19).

“A Flash of Lightening” by Buson

A flash of lightning!

Girdled by the waves,

“Autumn-Islands.” (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 277).

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes:

“Of all ukiyo-e prints of lovers, this one creates the most romantic and melancholic mood. Harunobu emphasizes the intimacy of two lovers strolling in the snow, even suggesting perhaps a michiyuki, a path to a love suicide. The couple walk together in the quietly falling snow, in what is known as an ai ai gasa pose, literally, the sharing of an umbrella and love.

Harunobu, the originator of the polychrome print, or nishiki-e, shows his mastery of color, rendering the couple’s robes in paired black and white, characterized as “crow and heron.” In contrast to the plain colors, he decorates both the inner robe and the obi of each figure with elaborate polychrome patterns. Embossing brings out the soft, flaky texture of the snow and the patterns of the woman’s kimono and hood. This print is an early impression of this design, which was re-engraved, with slight changes, during Harunobu’s lifetime or shortly afterward.”

“Passing through this World” by Iio (or Ino) Sōgi

Passing through this world,

We shelter as we may

From the winter rain. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 51).

“The Snow and Snow” by Matsuo Bashō

The snow and snow.

This evening would have

The great moon of December.

“The First Winter Shower” by Basho

The first winter shower;

My name shall be

“Traveller,” (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 122).

“Lo, an Autumn Eve!” by Jakaren Hoshi

Lo, an autumn eve!

See the deep vale’s mists arise

Mong the fir-tree’s leaves

That still hold the dripping wet

Of the (chill day’s) sudden showers.

Haiku and Ukiyo-e Seasons and Ecoscapes

Courtesy: Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke and Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation Gifts, 1987. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44523” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

The Divine in Nature: Haiku, Tanka, and Art Images

A reverence for life, a recognition of the ephemeral, and dimensions of the mysterious and are celebrated in Haiku nature poetry. Nigel Cawthorne (1997) writes: “The Japanese have always shown a great reverence for nature. They would hold parties to watch the sky and compose poetry at New Moon. Or they would gather together to view a cherry tree that had recently come into blossom, admire the red autumn leaves of the maple or watch the first new fall of winter snow.”(p.83).Expressions of the divine are apparent in natural phenomena; the rising of the sun, the seasons, flower, a leaf, a mountain, a small animal, and a blade of grass are unique in their beauty and significance. The celebration of their unique beauty can be found in the Ukiyo-e style of woodblock prints and in Japanese poetry.

Of the value of poetry, Yone Noguchi (1915) writes:

“To-day we must readjust the meanings of all things or give a new interpretation to all the old meanings ; and we must solve the problem of life and the world from our real obedience to laws and knowledge that will make the inevitable turn to a living song, and learn the true meaning of time from the evanescence of psychical life; then our human lives will become true and living. We must realize the ephemeral aspect of moments when time moves, and also the still aspect of infinity when it settles down ; seek the meaning of moments out of the bosom of infinity, and again that of infinity from the changing heart of moments—that is the secret of real poetry. The moments that suggest the still aspect of infinity are accidental, therefore living ; again the infinity that is nothing but another revelation of moments is absolute, therefore quiet and full of strength and truth. The real poetry should be accidental and also absolute. See the river and trees, see the smiling garden flowers, see the breaking clouds of the sky. See also the lonely moon walking a precipitate pathless way through the clouds. The natural phenomena are, under any circumstances, revealing both meanings of the accidentalism which is born from the absolute. When our great poets of Japan write only of a shiver of a tree or a flower, of a single isolated aspect of nature, that means that they are singing of infinity from its accidental revelation.” (Noguchi, The spirit of Japanese art, 1915, p. 1).

“Tis the spring day” by Ki no Tomonori

Tis the spring day

With lovely far-away light . • ,

Why must the flowers fall

With hearts unquiet ? (Trans. by Noguchi, The spirit of Japanese poetry, John Murray Publishing, 1915, p. 115).

Courtesy: Purchase with support from the Rembrandt Association and the Ministry of Education, Arts and Sciences. “http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.46050” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

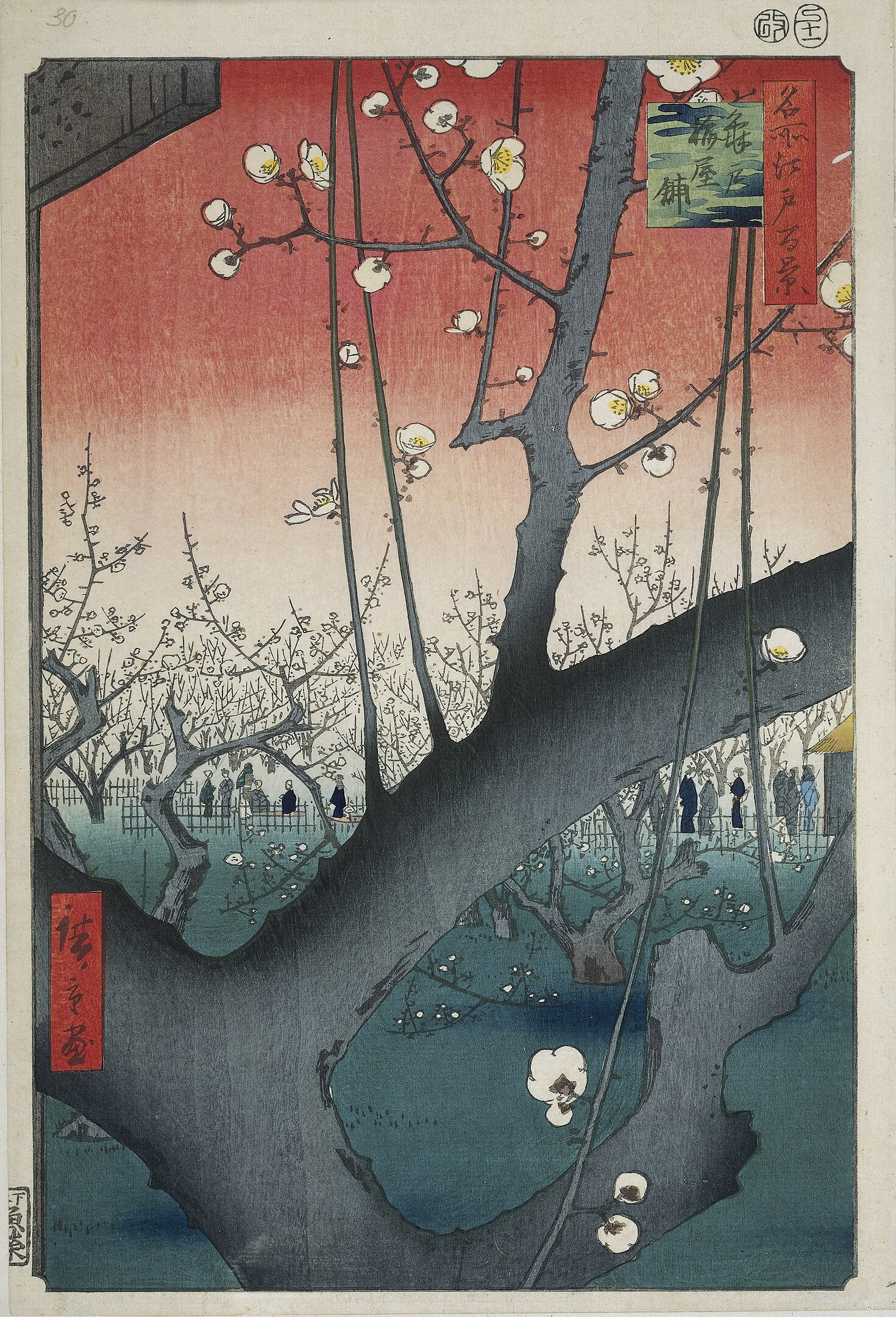

About the Painting

Museum Note about the Painting

“Hiroshige brings us face to face with the celebrated “Sleeping Dragon Plum” of Kameido. This tree, the most famous in Edo, was known for the purity of its double blossoms, which, according to one Edo guidebook, were “so white when full in bloom as to drive off the darkness.” We are so close that we can almost smell the tree’s powerful fragrance, reputed to have lured the shogun Yoshimune as he passed nearby in the early eighteenth century.” (Brooklyn Museum Notes).

“The Spring Haze” by Matsuo Bashō (Translations from Reginald Horace Blyth)

The spring haze.

The scent already in the air.

The moon and ume.

“Suddenly the Sun Rose” by Matsuo Bashō (translation by R.J. Blyth, 1963, p. 102)

Suddenly the sun rose,,

To the scent of the plum-blossoms

Along the mountain path

“From the Heart of the Spring” by Kamo Mabuchi

From the heart

Of bright and balmy spring

Are wafted forth

These mountain cherries. (Translated by R.H. Blyth, Haiku Volume 1: Eastern Culture, 1949/1981, The Hokuseido Press, p. 113).

“Lighting One Candle” by Buson

Lighting one candle

With another candle,

An evening of spring. (Trans. by Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 113).

About the writer and translator Reginald Horace Blyth (1898-1964)

Writers such as Reginald Horace (R.H.) Blyth (1898-1964) ventured to Japan and were among the first Western writers to translate Japanese poetry, including Haiku, Tanka, and other verse into English. Blyth was known for his writing about Zen and Haiku poetry. Blyth saw close parallels between the writing of Henry David Thoreau and other transcendentalist writers and Haiku poetry and its emphasis on nature and existential themes. Blyth’s Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics (1949-1952) along with his five-volume Zen series were published in Japan, by Hokuseido Press, Tokyo. Many of Blyth’s works can now be accessed online. H.R. Blyth, Tone Noguchi, and Harold Gould Henderson made major contributions with their English translations of Haiku poetry (and other Japanese poetry forms).

From “Zen” (R.H. Blyth, 1949, Haiku: Volume 1 Eastern Culture, Hokuseido Press and Heian International.

Zen world views

Mountains and rivers, the whole earth, —

All manifest forth the essence of being.

The wind drops, but the flowers still fall;

A bird sings, and the mountain holds yet more mystery.

The plum tree, dwindling, contains less of the spring;

But the garden is wider, and holds more of the moon.

The tree manifests the bodily power pf the wind;

The wave exhibits the spiritual nature of the season.

Words do not make a man understand;

You must get the man to understand them.

The old pine-tree speaks divine wisdom;

The secret bird manifest eternal truth.

(Blyth, 1949/1981, pp. 28-30)..

The imagist poet Robert Gould Fletcher (1886-1950) was influenced by Japanese art and Haiku when he wrote Japanese Prints in 1918. To read more of Fletcher’s poems from Japanese prints please click here.

“Court Lady Standing Under Cherry Tree” by John Gould Fletcher

Dark purple, pale rose,

Under the gnarled boughs

That shatter their stars of bloom.

She waves delicately

With the movement of the tree.

Of what is she dreaming?

Of wine cups and compliments and kisses of the two-sword men.

And of dawn when weary sleepers

Lie outstretched on the mats of the palace,

And of the iris stalk that is broken in the fountain. (John Gould Fletcher, Japanese Prints, Four Seas Co., 1918, p. 23).

“Coming to the Mountain Village” by Noin Hoshi (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949/1981)

Coming to the mountain village

One spring evening,

The bell was sounding,

Flowers falling.

Source: Haiku Volume 1, Eastern Culture, p. 114. Blyth, R.H. (1949/1981). Haiku Volume 1: Eastern Culture. The Hokuseido Press and Heian International.

“Still I Would Fain See” by Matsuo Bashō (Translation by R. J. Blyth)

Still, I would fain see

The god’s face

In the dawning cherry blossoms. (translated by R.H. Blyth, 1963, p. 116).

“Flower-viewing” by Asukai Masatsune

Flower-viewing,

Shadows of evening fall,

But unawares,

Through the trees,

Together with me. ( Trans. by R.H. Blyth, 1964, p. 120).

Courtesy: By Yoshitoshi – National Diet Library Digital Collections: Persistent ID 1301407, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=100053509

“Gaze I at the moon” by Oe no Chisato

Gaze I at the moon,

Myriad things arise in thought,

And my thoughts are sad,

Yet, ‘tis not for me alone,

That the autumn has come.” (trans. by Clay MacCauley)

“Buddha” by Matsuo Bashō

Buddha

Is the cherry blossoms

On a moonlit night. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 135).

“The Water-Spirit” by Yosa Buson

The water-spirit

In his abode of love,

Under the summer moon. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 266).

“A Crescent Moon” by Taigi

A crescent moon,

As I sit in the boat,

The moonlight is on my lap. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 301).

Courtesy: Gift of H. R. Warner. “https://www.artic.edu/artworks/11054/no-32-seba-from-the-series-sixty-nine-stations-of-the-kisokaido-kisokaido-rokujukyu-tsugi-no-uchi” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“Like a mariner” by Sone no Yoshitada

Like a mariner

Sailing over Yura’s strait

With his rudder gone,–

Whither, o’er the deep of love,

Lies the goal, I do not know (translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917).

“Seeing the heat waves” by Hitomaro

Seeing the heat waves

Over the eastern moor,

I look back,

And there was the moon,

Sinking. (Trans. by R.H. Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 115).

“The Autumn Fall Moon” by Matsuo Bashō

The autumn full moon;

The foaming tide

Rolls up to the gate. (Trans. by Blyth, A history of haiku, 1963, p. 117).

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes

“Ukiyo-e represents the final phase in the long evolution of Japanese genre painting. Drawing on earlier developments that had focused on human figures, ukiyo-e painters focused on enjoyable activities in landscape settings, shown close-up, with special attention to contemporary affairs and fashions. As artists chose subjects increasingly engaged in the delights of city life, their interest shifted to indoor activities. The most favored subjects of painting in the early seventeenth century were scenes of merry-making at houses of pleasure, especially in the notorious Yoshiwara quarter of Edo. About the time of the Kanbun era (1661–72), actresses and the alluring courtesans of Yoshiwara were singled out for individual portrayal, often a scale larger than usual and garbed in opulent costumes.

Portraits of famous courtesans and actors were made more accessible to a mass audience in the form of inexpensive woodblock prints. The method of reproducing artwork or texts by woodblock printing was known in Japan as early as the eighth century, and many Buddhist texts were reproduced by this method. Until the eighteenth century, however, woodblock printing remained primarily a convenient way of reproducing written texts. What ukiyo-e printmakers of the Edo period achieved was the innovative use of a centuries-old technique.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, woodblock prints depicting courtesans and actors were much sought after by tourists to Edo and came to be known as “Edo pictures.” In 1765, new technology made possible the production of single-sheet prints in a range of colors. The last quarter of the eighteenth century was the golden age of printmaking. At this time, the popularity of women and actors as subjects began to decline. During the early nineteenth century, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) brought the art of ukiyo-e full circle, back to landscape views, often with a seasonal theme, that are among the masterpieces of world printmaking (JP1847).

In the decade following the death of Hiroshige, in 1858, the major printmakers disappeared in the brutal sociopolitical upheavals that brought down the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867. Edo’s society, the mainstay of ukiyo-e art, underwent a drastic transformation as the country was drawn into a campaign to modernize along Western lines. Like many other elements of Japanese culture, ukiyo-e was swept away in the maelstrom that heralded the coming of a new age.”

Citation

Department of Asian Art. “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm (October 2004)

“Flower Viewing” by Masatsune (translated by H.R. Blythe, 1949/1981, p. 120).

Flower viewing,

Shadows of evening fall,

But unawares,

Through the trees,

The moon over the mountain.

“The Moon” by Kotomichi Okuma (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 120)

Coming back with me

From the mountains,

Entered the gate,

Together with me.

Source: Blyth, R.H. (1949). Haiku, Volume 1 Eastern Culture. The Hokuseido Press and Heian International.

Courtesy: Purchase with support from the Rembrandt Association and the Ministry of Education, Arts and Sciences. “http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.46064” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

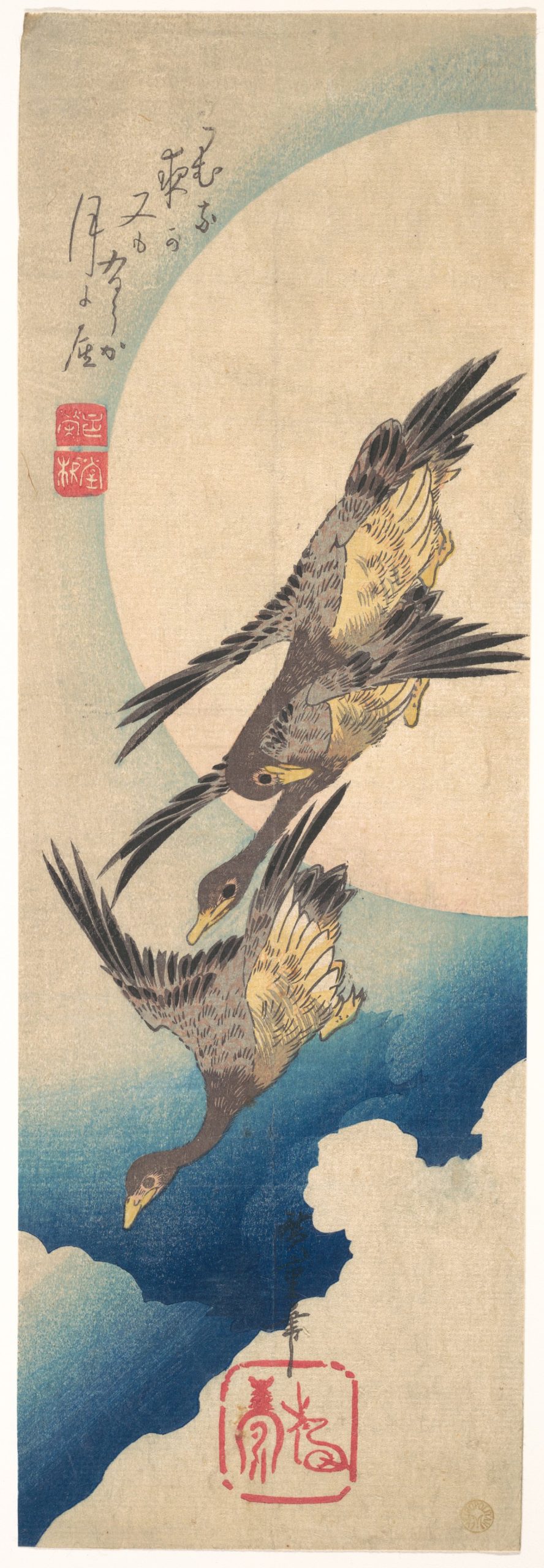

“More than a Dream” by Matsuo Bashō

More than a dream

The Reality of a hawk

We can rely on.

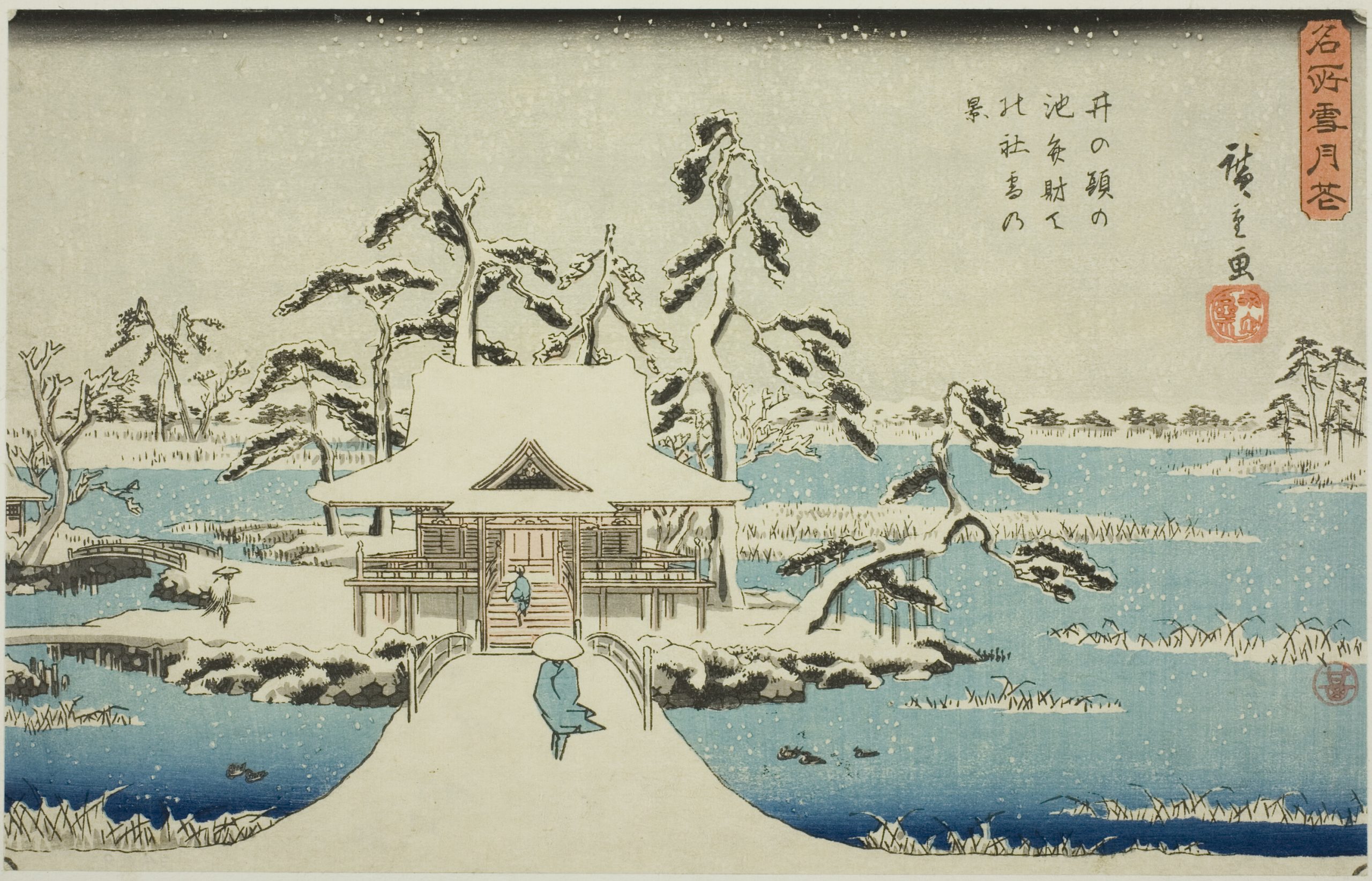

Courtesy: Clarence Buckingham Collection. “https://www.artic.edu/artworks/19040/snow-at-benzaiten-shrine-in-inokashira-pond-inokashira-no-ike-benzaiten-no-yashiro-yuki-no-kei-from-the-series-snow-moon-and-flowers-at-famous-places-meisho-setsugekka” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“Winter Loneliness” by Minamoto no Muneyuki AsonWinter loneliness

In a mountain hamlet grows

Only deeper, when

Guest are gone, and leave and grass

Withered are; so runs my though (translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917).

“Snow Remaining” by Sogi

Snow remaining,

The foot of the mountain is covered with mist,

This evening! (trans. by Blyth, 1963, The history of haiku, Vol. 2, p. xv).

“They Wouldn’t Put Me Up” by Yosa Buson

They wouldn’t put me up;

The flickering lights

Of several adjacent houses in the snow. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 376).

Museum Note about the Artist Utagawa Hiroshige

“Utagawa Hiroshige is recognized as a master of the ukiyo-e woodblock printing tradition, having created 8,000 prints of everyday life and landscape in Edo-period Japan with a splendid, saturated ambience. Orphaned at 12, Hiroshige began painting shortly thereafter under the tutelage of Toyohiro of the Utagawa school. His early work of narrow, vertical landscapes picturing thatched houses nestled between cliffs and vignettes of birds perched on flowering branches shows the influence of Chinese scroll painting as well as the previously dominant Kanō school of Japanese painting. Much of Hiroshige’s work focuses on landscape. Partly inspired by Katsushika Hokusai’s popular Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, Hiroshige took a softer, less formal approach with his Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido (1833–34), completed after traveling that coastal route linking Edo and Kyoto. Mountains grow green and bands of salmon-colored sunrise hang in the mist in prints like Maisaka—No. 31, where traders and farmers mundanely pass by in the foreground.”

Courtesy: By Yoshitoshi – National Diet Library Digital Collections: Persistent ID 1301406, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=100053466

on my horse’s back

Courtesy: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/53423” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Museum Note about the Painting

“Paintings of cherry trees in isolation are surprisingly rare, considering they are the quintessential symbol of Japan. The cherry tree serves in literature and painting as an emblem of spring or an allusion to certain famous sites (meisho) such as Yoshino, near Nara. This small-screen composition—which originally probably lacked the wide silver band at the bottom—illustrates Sakai Hōitsu’s unerring sense of space, created here by an expanse of gold leaf. “

“Let us, each for each” by Saki no Daisojo Gyoson

Let us, each for each

Pitying, hold tender thought,

Mountain-cherry flower!

Other than thee, lonely flower,

There is none I know as friend. (trans. by Clay MacCauley, 1917).

Courtesy: Rogers Fund, 1914. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36537” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“My Desire” by Saigyō Hōshi

My desire

Is that I may die

Beneath the cherry blossoms,

In spring,

On the fifteenth night

Of the second month. (Trans. by Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 112).

“The Temple Evening” by Taigi Sumi

The temple evening;

The dust is all

Cherry-blossoms. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 304).

“Towering over the Japanese landscape and consciousness, Mount Fuji can be seen even from dis”tant points, as Hiroshige showed in many views of the peak from the city of Edo-now Tokyo—and rural villages, in close-up and from far away. In this one, he frames the sacred mountain, a symbol of Japan itself, with another iconic image, the flowering plum trees. As one of the earliest trees to blossom, even on bare branches, the plum signifies perseverance as well as beauty, longevity, and the return of spring” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Flowers, 2022 Engagement Book, February/March. Abrams, New York).

For more examples of Utagawa Hiroshige’s Views of Mount Fuji please open the link here.

“Evening Quiet” by Bai Juyi (Hakurakuten)

Early cicadas stop their trilling;

Points of light, new fireflies, pass to and fro.

The taper burns clear and smokeless;

Beads of bright dew hang on the bamboo mat.

Not yet will I enter the house to sleep,

But walk awhile beneath the eaves.

The rays of the moon slant into the low verandah;

The cool breeze fills the tall tress.

Letting loose the feelings, life flows on earlier;

The scene entered deep into my heart.

What is the secret of this state?

To have nothing small in one’s mind. (Trans. by Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 164).

“We are obedient” by Onitusura

We are obedient,

And silent flowers too

Speak to the inner ear. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 99).

“The Moon, and the Cherry Blossoms” by Teitoku

The moon, and the cherry blossoms, —

Now I know, in this world,

What the third verse is. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p.68)

“From the heart” by Kamo Mabuchi (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949/1981, p.113).

Of bright and balmy spring

Are wafted forth

These mountain cherry flowers.

“Lighting one candle” by Buson (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 113).

Lighting one candle

With another candle

An evening of spring.

“Seeing the heat waves” by Hitomaro (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949/1981,p. 115).

Over the eastern moor,

I looked back,

And there was the moon,

Sinking.

Source: Blyth, R.H. (1949). Haiku: Volume 1 Eastern Culture. The Hukuseido Press and Heian International.

Courtesy: By Utagawa Hiroshige – Museum of Fine Arts Boston, William Sturgis Bigelow Collection https://collections.mfa.org/download/217834;jsessionid=42B4232FD10E6E81A7EB7C8DD419B5A0, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98808403

“The Cherry Blossoms” by Matsuo Bashō

The cherry blossoms,

Returning at dawn from the Yoshiwara;

Was it the goddess of Mt. Katsuragi? (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 99)

“Color of the flower” by Ono no Komachi

Color of the flower

Has already passed away

While on trivial Things

Vainly I have set my gaze,

In my journey through the world (translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917)

“O ye Winds of Heaven!” by Sojo Henjo

O ye Winds of Heaven!

In the paths among the clouds

Blow, and close the ways,

That we may these virgin forms

Yet a little while detain. (translated by Clay MacCauley, 1917)

“Untitled Poem” by Matsuo Bashō

From among the peach-trees

Blooming everywhere,

The first cherry blossoms.

The sound fades,

The scent of flowers arises,

The bell struck in the evening.

In the midst of the plain

Sings the skylark,

Free of all things. (Trans. by Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 36).

Courtesy: Gift of the Estate of Charles A. Brandon, by exchange; purchased with funds given by Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Danziger, Joan Easton, Mrs. Myron S. Falk, Jr., George S. Friedman, Mr. and Mrs. Mark Kingdon, Klaus F. Naumann, Robert Rosenkranz, and Mr. and Mrs. David Young and Asian Art Acquisition Fund. “https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/154420” has No known copyright restrictions.

Courtesy: By Utagawa Hiroshige I, published by Uoya Eikichi (1797 – 1858) – Artist (Japanese)Details on Google Art Project – qgFCjAmgF1vaxA at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22140632

“O Irises” by Sogi

O irises!

Think of the journeys

Of those who see you! (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 48).

“Talking Before the Iris Flowers” by Matsuo Bashō

Talking before the iris flowers:

This is also one of the pleasures

Of travelling. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 113).

“In the village of Horikiri in suburban Edo, gardeners grew a year-round variety of flowers and were particularly famous for the iris shown here, “hanashobu,” well suited to this swampy land. In this print Hiroshige has shown three, almost-life-size, detailed specimens of the nineteenth-century hanashobu hybrids and in the distance, sightseers from Edo are admiring the blossoms. In the 1870’s the cultivation of hanashobu had begun to spread rapidly in Europe and America and the developed into a booming export market for the gardeners of Horikiri. The Horikiri plantations began to wane in the 1920’s and eventually turned over to wartime food production. After the war, one of them was revived and is now a public park, particularly popular in May when the flowers are in bloom.”

Courtesy: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. C. R. Snell, Jr., 1987. “https://art.thewalters.org/detail/35995/nihon-hana-zue-11/” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“Gazing and gazing” by Soin

At the cherry blossoms–

What are my feelings!

But when they fall and depart,

How sad I am. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 79).

“White plum-blossoms” by Buson

White plum-blossoms;

Mother of pearl

Is spilt on the table. (Trans. by H.R. Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 257).

“Between our two lives, there is also the life of the cherry blossom.” – Matsuo Bashō

For Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694), cherry blossoms, the light spring rain, and the song of a skylark were momentarily fragments of a “floating world” that was both beautiful and ephemeral. Life was precious and each moment should be treasured, due to the transitory nature of all living things. For further information please open the links here, here and here.

Courtesy: By Kitagawa Utamaro – Sotheby’s – https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2022/china-5000-years/kitagawa-utamaro-1754-1806-two-woodblock-prints, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=121053254

“In the mountain depths” by Sarumaru Tayu

In the mountain depths,

Treading through the crimson leaves,

Cries the wandering stag.

When I hear the lonely cry,

Sad,-how sad-the autumn is. (Translated by Clay MacCauley)

Courtesy: By Utagawa Kunisada II – mfa.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77138477

“In the dusk, the breeze is fragrant” by Otsuji Osuga (Translated by R.H. Blyth, p. 121)

In the dusk, the breeze is fragrant

A maiden bringing the tea

To the football garden.

Courtesy: “Two women in the rain” obtained from Artvee is in the Public Domain.

“Spring Rain” by Yosa Buson

telling stories,

a straw coat and umbrella walk past.

With a sudden, awe-inspiring sound

Above the forest. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 304).

A flash of lightning” by Buson (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949, p. 241)

A flash of lightning!

The sound of drops

Falling among the bamboos. (translated by R.H. Blyth, 1949, p. 241).

Source: R.H. Blyth (1949/1981). Haiku: Volume 1 Eastern Culture. The Hokuseido Press and Heian International.

Courtesy: Gift of Anna Ferris. “https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/121658” has No known copyright restrictions.

Courtesy: Purchase, Arthur Wiesenberger Foundation Gift, Louis V. Bell Fund, Bequest of Dorothy Graham Bennett, and Pfeiffer and Seymour Funds, 1972. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45744” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes

“Gardens planted to evoke deserted fields of autumn wildflowers inspired poets and artists in many media: painting, ceramics, lacquer, and textiles. Eulalia and Japanese bush clover were the most appreciated of the autumn plants for their appearance of wildness and abundance when waving in the wind, as well as for their suggestion of melancholy when withered.

Many screens similar to this pair have been attributed to the Hasegawa school, founded by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539–1610). The highly dramatic depiction of the grasses—with their rhythmic arrangement into clumps and sharp angling at the bottom to hint at a recession into space—suggests that the screens were produced by a Hasegawa painter in the first half of the seventeenth century. To create their signature mode of representation, Hasegawa artists made determined efforts to assimilate all available techniques of painting, from the famed Tosa-school style to methods used by artists employed by ready-to-sell painting shops. They and their patrons especially favored the subject of autumn grasses.”

Courtesy: Gift of Anna Ferris. “https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/121724” has No known copyright restrictions.

“In This World of Ours” by Buson

In this world of ours,

So long as it may last,

Whatever may happen,

Shrines and thatched house

Are no different from one another. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 347).

Courtesy: By Utagawa Hiroshige – http://visipix.com/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=354805

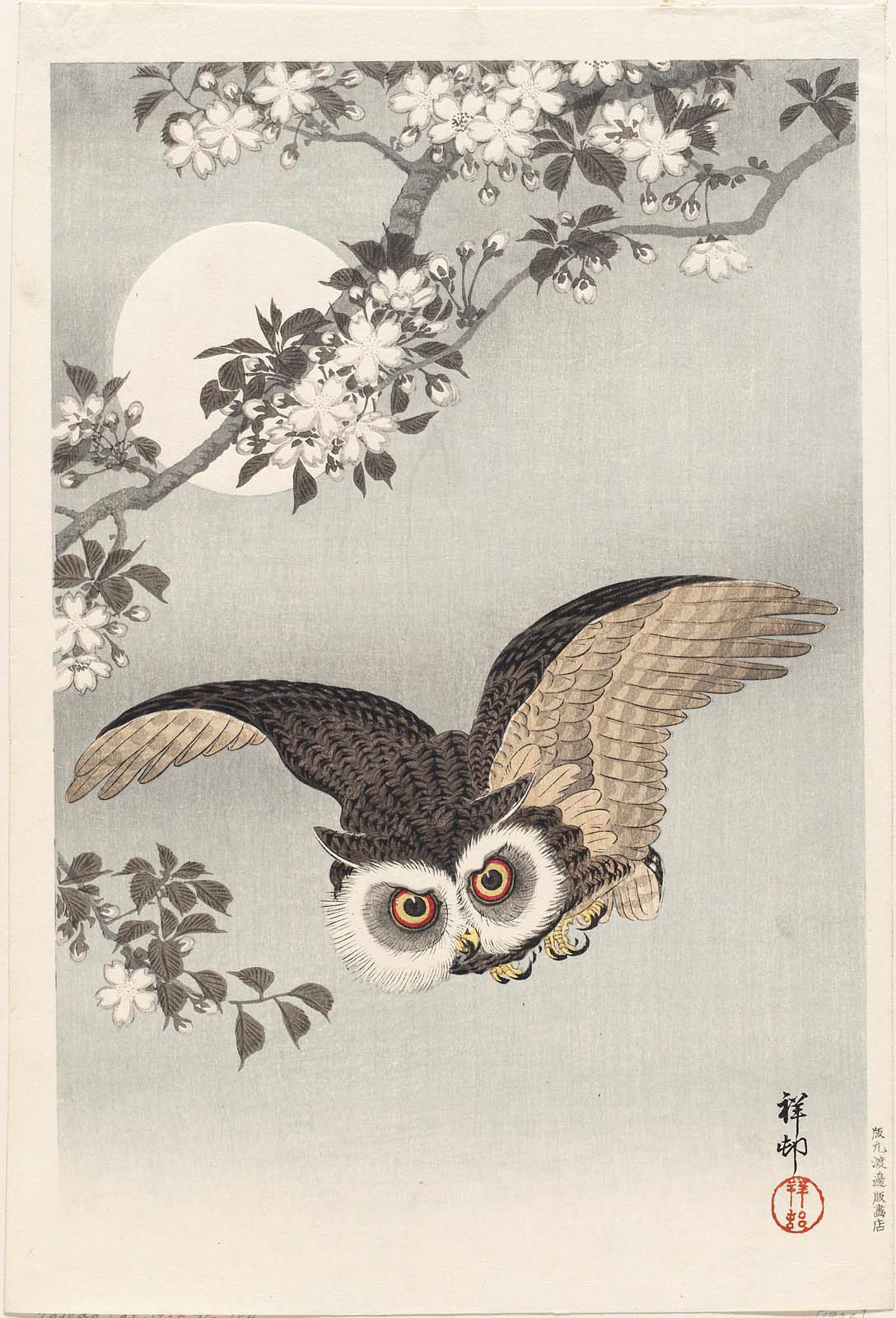

Courtesy: By Ohara Koson – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2305689749663567, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76211040

“Were They Voiceless” by Fukudo Chiyo-e (Chiyo)

Were they voiceless,

The herons would be almost non-existent,

This morning of snow. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 323).

“Winter Haiku“ by Yosa Buson

Miles of frost –

On the lake

The moon’s my own.

Courtesy: Donation from Mr J. Perrée, Eindhoven. “http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.360910” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“On Land and Water” by Otokuni

On land and water,

The birds set up their cries

At the snow-storm. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 194).

“A Nameless Bird” by Sampu

A nameless bird

Looks cold

In the wintry blast. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 157).

Haiku Ecoscapes: Poetry and Art Images

Haiku (translated as unusual verses) poetry is rich, varied, and accessible. In this section, some of the great Japanese Haiku poets are featured with complementary artistic images. Over the years, there has been a move away from the more restrictive 5-7-5 syllable count to one and three lines with no set syllable count. Influential haiku poets include Matsuo Basho, Kobayashi Issa,and Masaoka Shiki. In their original form, haiku were the introductory verses of longer poems called tanka, but they have become popular as a form in their own right since the seventeenth century. The Japanese Tanka poem describes an event or haiku eludes an exact definition and categorization; Haiku can best be viewed as evolving, growing, and flourishing. A number of Haiku poets were Zen masters pursuing a path of spiritual enlightenment; a deep reverence and empathy for nature led Matsuo Basho to state: “Learn about a pine tree from a pine tree, and about a bamboo plant from a bamboo.” (Van den Heuvel, 1986, p. 20).The visual imagery in Haiku is transcendent and ephemeral. Harold Henderson notes that haiku verses are meditative and Zen like. Haiku nature poems are prescient today in a world of precious resources, species decline and extinction, and ever-present environmental catastrophes. A search to restore the grandeur of nature is a challenge of our time. Haiku poems are a catalyst to awareness and empathy. Life is illuminated in a concise and vivid way. Early on, R.H. Blyth (1949) writes:

A haiku is the expression of a temporary enlightenment, in which we see into the life of things….It is a way in which the cold winter rain, the swallows of evening, even the every day in its hotness, and the length of the night become truly alive, share in our humanity, speak their own silent and expressive language. (p.p. 270, 272).

Blyth further noted:

” Haiku is an ascetic art, an artistic asceticism. Of the two elements, the ascetic is more rare, more difficult, of more value than the artistic. For this reason, Wordsworth remains the least understood of English poets, and has no disciples, or even imitators. Art is something that every woman is born with; every man begins to be a kind of artist when he falls in love. Asceticism is found, it is true, whenever a man gives up pleasure for pain, happiness for blessedness, when for example an athlete makes himself mentally and physically fit for a contest, but the asceticism spoken of here is not a means to an end. It is an end in itself, and therefore cannot be questioned; it cannot be explained or justified.” (R.H. Blyth, 1963, pp. 7-8).

As you read the poems in this section and view the complementary art images, you can jot down your own thoughts and ideas.

Key Takeaways

- Haiku

Haiku poems originated in 17th century Japan; the unrhymed 17 syllables organized in three lines were a reaction to the elaborate formal poetic traditions. Haiku evolved into an art form with like the influence of poets like Bashō (1644-1694). Bashō was introduced to poetry early in his life and became well known in intellectual circles of Edo (modern Tokyo). He worked as a teacher but in a quest to learn more about the world, renounced the social and cultural networks in order to travel and gain firsthand experiences. Nature was a profound source of inspiration for Basho. In many Haiku poems, there is:

- a focus on themes of nature or seasons

- the juxtaposition of asymmetrical sections (e.g. pairing seemingly unexpected things or positioning something from nature and something human made)

- elegance and precision of words

- an existential insight, observation, and reflection

- a reverence of nature (landscapes, animals, flowers, birds)

- inclusion of figurative language such as imagery over metaphor, simile, or exposition

- non-rhyming organization of lines

- a wistful and contemplative tone (for more details please open the Wikipedia link here

Practical tips for writing Haiku poems are included below.

Additional Poetry Resources (NCTE):

Sketches of Life in Art and Haiku Poems

“Passed the First Day of Spring” by Matsuo Bashō

Passed the first day of spring,

It’s only nine days

On the hills and fields.

“Oh, these spring days!” by Matsuo Bashō

Oh, these spring days!

A nameless little mountain,

wrapped in morning haze!

“A Dewdrop Fades” by Kobayashi Issa (Translation by Harold Henderson, 1967 p. 50)

A dewdrop fades away:

It’s dirty, this world, and in it

There’s no place for me.

Poem by Buson (translations from R.H. Blyth)

Spreading a straw mat in the field,

I sat and gazed

At the plum blossoms.

“Autumn” by Matsuo Bashō (Translation from Blyth)

The autumn full moon:

All night long

I paced round the lake.

Reginald Horace Blyth (1898 – 28 1964)-Translator of Japanese Haiku. R.H. Blyth was a specialist in Japanese culture and became well-known as a translator and writer of Zen perspectives and Haiku poetry.

Source: Internet Archive eBook: Zen in English and Oriental Classics, Dutton, 1960.

“On a Withered Branch” by Bashō (trans. R.H. Blyth, 1949, p. 89)

On a withered branch,

A crow is perched,

In the autumn evening.

Courtesy: By Ohara Koson – Woodblock print circa 1910 by Ohara Koson (1877-1945), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36393309

R.H. Blyth’s Reflections about Bashō and a Reverence for Life and the Divine in Nature:

“To be incapable of a feeling of poetry, in my sense of the word, is to be without love of human nature and reverence for God.

Bashô felt that life was not deep enough, not continuous enough, and he wanted to give every action, every moment the value that it potentially had. He wanted the little life we lead to be at the same time the greater life. Every flower was to be the spring, every pain a birth pang, every man a haiku poet, walking in the Way of Haiku.

It was the life of the little day, the life of little people. And the man who had died said to himself, “Unless we encompass it in the greater day, and set the little life in the circle of the greater life, all is disaster.” (Blyth, 1949, p.328)

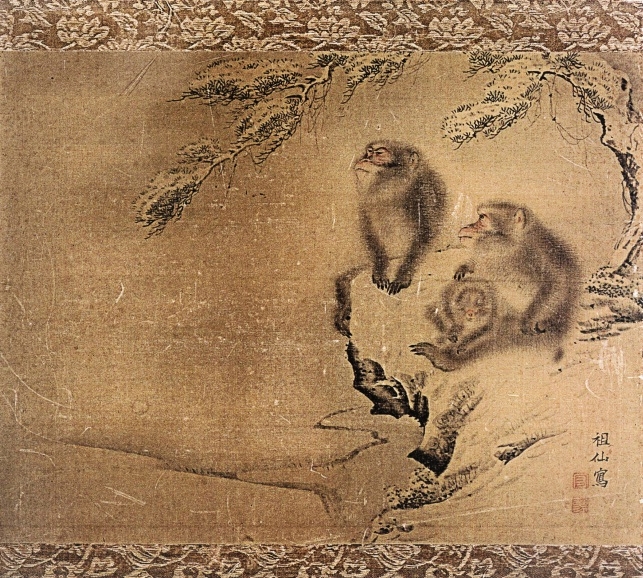

Mori Sosen (1747-1821). Monkeys in the Snow (late 18th century). The National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland. Public Domain.

Courtesy: By Mori Sosen – Dorota Folga-Januszewska (2005). Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie : arcydzieła malarstwa. Arkady. ISBN 83-21343-31-7, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22750646

“First Winter Rain” by Matsuo Bashō

by Matsuo Basho

First winter rain;

The monkey also seems to wish

For a small straw rain-coat. (Trans. by Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 93)

“What was it that made Bashō suddenly realise that poetry is not beauty, as in waka, or morality, as in dōka, or intellectuality and verbal wit as in haikai? Some say it was the result of his study of Zen, but this seems to me very unlikely. Bashō does not seem to have urged his disciples to do zazen, and seldom speaks about Zen and its relation to haiku.

The fact is that haiku would have come into being even if Bashō had never been born. We cannot say, however, that somebody would have written Shakespeare’s plays even if Shakespeare (or Bacon or Marlowe or the Earl of Oxford or Queen Elizabeth) had not. What Thoreau said, that “Man, not Shakespeare or Homer, is the great poet,” is truer of Japan than of any other country, where custom and tradition are stronger, and where the poetry was not a romantic or classical solo, but a democratic trio or quartet. Again, as was noted before, Onitsura, Gonsui, and many lesser men were composing good haiku at the same time as Bashō. However, they did not have the modesty, the generosity, the ambitionlessness of Bashō. Onitsura loved sincerity and truth and made them his object, but Bashō just loved.” (p.349-350).

To read more poems by Basho please click on this link :Haiku Poems by Matsuo Basho.

Adachi Woodcut Prints from the Ukiyo-e series (Art Note):

“Mount Fuji with Cherry Trees in Bloom” was created when Hokusai was in his forties, around the time he called himself “Gakyojin” or “Man Crazy about Drawing.” It captures a beautiful springtime scene with cherry trees in full bloom overlapping one another, a spring haze wafting around them, and the sacred Mount Fuji with a dusting of snow in the background. Hokusai depicted the majestic mountain throughout his life and was known as “the artist of Mount Fuji.” However, this is a hidden masterpiece that few people know about, and only a very small number of prints are in existence today. The piece, with a beautiful composition of Mount Fuji and cherry trees in full bloom, is a representation of a scene the Japanese hold near and dear to their heart. Pale colors are printed over one another numerous times to create elegant and sophisticated shades of color, and a printing technique called “karazuri” is used to create an embossed effect, giving dimension to the petals of the cherry blossoms.”

To read more about the artist Hokusai and view more of his art please open the links below:

“A Poppy Blooms” by Katsushika Hokusai

I write, erase, rewrite

Erase again, and then

A poppy blooms.

Courtesy: Clarence Buckingham Collection. “https://www.artic.edu/artworks/25108/poppies-from-an-untitled-series-of-flowers” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

The poppy plant was grown in the Mediterranean region as early as 5000 B.C., but is now grown in many countries world wide. Poppies are often associated with death, rest, a keen mind, beauty, success, and eternal life. The Edo period (1615–1868) of Japan was a time of creative flourishing and artists focused on design, print making with a focus on elevating the intricate beauty of nature. Many beautiful Haiku poems were written during this time; some artists also wrote Haiku to accompany their art images. We see this complementarity with Hokusai’s poppy image and poem.

“What about my songs?” by Yone Noguchi

The known-unknown-bottomed gossamer waves of the field

are coloured by the travelling shadows of the lonely,

orphaned meadow lark:

At shadeless noon, sunful-eyed,—the crazy, one-inch butterfly

(dethroned angel ?) roams about, her embodied shadow

on the secret-chattering hay-tops, in the sabre-light.

The Universe, too, has somewhere its shadow ;

—but what

about my songs ?

An there be no shadow, no echoing to the end, —my broken-

throated flute will never again be made whole. (Yone Noguchi)

“Court Lady Standing under Cherry Tree” by John Gould Fletcher

Of what is she dreaming?

Of long nights lit with orange lanterns,

Of wine-cups and compliments and kisses of the two-sword men.

Courtesy: By Kitagawa Utamaro – Library of Congress[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5794844

“Utamaro’s Portraits” by Tone Noguchi

She is an art (let me call her so)

Hung, as a web, in the air of perfume,Soft yet vivid, she sways in music:

(But what sadness in her saturation of life!)

Her music lives in intensity of a moment and then dies;

To her, suggestion is her life.

She is the moth-light playing on reality’s dusk,

Soon to die as a savage prey of the moment;

She is a creation of surprise (let me say so),

Dancing gold on the wire of impulse.”

From: The spirit of Japanese art by Tone Noguchi, 1883/1915, John Murray Publishing, p. 33

English: Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Ase o fuku onna (Woman wiping sweat). Print shows a head-and-shoulders portrait of a young woman wiping her face. 1 print : woodcut, color.

(Library of Congress). By Kitagawa Utamaro – Library of Congress[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5794844

“Hydrangeas” by Masaoka Shiki

Hydrangeas

Pale blue in the rain

Blue in the moonlight

“Moods” by John Gould Fletcher

A poet’s moods:

Fluttering butterflies in the rain.

“Mid-Summer Dusk” by John Gould Fletcher

Swallows twittering at twilight:

Waves of heat

Churned to flames by the sun.

Courtesy: By Hiroshi Yoshida (1876 – 1950) (Japanese)Details on Google Art Project – 2wHA6qvg4l6i2g at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23685789

Impressions and Seasons

“Eight-fold cherry flowers” by Ise no Osuke

Eight-fold cherry flowers

That at Nara, –ancient seat

Of our State, —have bloomed; —

In our Nine-fold Palace court

Shed their sweet perfume today. (translated by C. MacCauley, 1917).

“Making us wait so long” by Sogi

Making us wait so long,

Yet falling so soon—

The soul of the cherry blossoms! ( Blyth, 1963, p. 48)

To read more Haiku about cherry blossoms please open the link here.

***************

“The sound of the water” by Sogi

The sound of the water;

Are the summer rains

At an end? (Blyth, 1963, p.49).

Journeys, Seasons, and Impressions of Nature (Poetry by Basho, translated by R.H. Blyth, 1963, Haiku Poetry)

“On a Journey” by Basho

On a journey;

My dreams wander

Over a withered moor ( translated by Blyth, 1963, p. 116).

“Clouds” by Basho

Clouds

Singing, singing,

All the long day ( translated by Blyth, 1963, 117).

“On the very day of Buddha’s Birth” by Basho

On the very day of Buddha’s birth

A young deer is born:

How thrilling! -Basho (trans. by Blyth, p. 102)

“I like to wash” by Matsuo Basho

I like to wash,

the dust of this world

In the droplets of dew.

“The summer grasses” by Basho (trans. by Blyth, 1949/1963)

The summer grasses,

All that remains

Of the warriors’ dreams. (p.26)

This autumn,—

Old age I feel,

In the birds,

In the clouds. (p.26)

A crow at rest

On a leafless bough

Autumn’s twilight (p. 116).

The autumn full moon;

The foaming tide

Rolls up to the gate. (p. 117).

The invisible colour

That fades,

In this world,

Of the flowers

Of the heart of man (Blyth, p. 128) From: A History of Haiku by R.H. Blyth (1963).

“To a sparrow” by Yone Noguchi

Sudden ghost

That danced out again from the shadow and rest,

Hunter of the memory and colour of thy last life,

Dost thou find the same humanity, the same dream?

Consecrator of every moment,

Holder of the genius for living.

Thy one moment might be our ten years :

Does it tempt, console and frighten thee ?

Ghost of nerve.

If thy voice be curse.

It is with all thy soul.

If it be repentance

It is with all thy body.

Oh, would that I could relish the same sensation as thou !

“Right and Left” by Yone Noguchi

The mountain green at my right :

The sunlight yellow at my left :

The laughing winds pass between.

The river white at my left :

The flowers red at my right :

The laughing girls go between.

The clouds sail away at my right :

The birds flap down at my left :

The laughing moon appears between.

I turned left to the dale of poem ;

I turned right to the forest of Love :

But I hurry Home by the road between.

Japanese Hokku (Haiku) by Yone Noguchi

About the writer Yonejirō (Yone) Noguchi (1875-1947)

Please click on this link to read more about the transnational writer Yone Noguchi (1875-1947).

Tone Noguchi was considered a cross-cultural, cosmopolitan, and transnational writer. In 1893 Noguchi moved to San Francisco where he worked as a journalist; he continued to publish his poems. He returned to Japan and his creative work continued to evolve. His books included The spirit of Japanese art and The spirit of Japanese poetry (archive.org). Noguchi influenced modernist and imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, Amy Lowell, John Gould Fletcher, and W. B. Yeats. The imagist poet John Gould Fletcher was highly influenced by Japanese Haiku and wrote Japanese Prints in 1918.

The Japanese Hokkus (Haiku) are from The Collected Poems of Yone Noguchi. (pp. 123-126), The Four Seas Company, 1921.

Japanese Hokkus (Haiku) by Yone Noguchi

What is life ? A voice,

A thought, a light on the dark,-

Lo, crow in the sky.

II

Sudden pain of earth

I hear in the fallen leaf.

” Life’s autumn,’I cry,

III

The silence-leaves from Life,

Older than dream or pain,—

Are they my passing ghost ?

(p. 124)

IV

Is it not the cry of a rose to be saved ?

Oh, how could I

When I, in fact, am the rose !

V

But the march to Life . • •

Break song to sing the new song !

Clouds leap, flowers bloom.

VI

Fallen leaves !

Nay, spirits ?

Shall I go downward with thee

By a stream of Fate ?

VII ,

Speak not again, Voice !

The silence washes off sins :

Come not again. Light !

VIII

It is too late to hear a nightingale ?

Tut, tut, tut, . . . some bird sings, —•

That’s quite enough, my friend.

IX

I shall cry to thee across the years ?

Wilt thou turn thy face to respond

To my own tears with thy smile ?

X

Where the flowers sleep,

Thank God ! I shall sleep, to-night.

Oh, come, butterfly !

XI

My Love’s lengthened hair

Swings o’er me from Heaven’s gate :

Evening’s shadow !

Japanese Hokkus

XII

Is there anything new under the sun ?

Certainly there is.

See how a bird flies, how flowers smile!

(pp. 123-126, T. Noguchi, Collected Poems, 1921).

Courtesy: Charles Stewart Smith Collection, Gift of Mrs. Charles Stewart Smith, Charles Stewart Smith Jr., and Howard Caswell Smith, in memory of Charles Stewart Smith, 1914. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54613” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“In this Fleeting World” by Kobayashi Issa

In this feeling world

Even that little bird

Makes himself a nest. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 394)

“I Too” by Issa

I too

have no dwelling place,

This autumn evening. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 394).

To read more and view paintings from the Edo period, please open the links below.

“The Butterfly” by Matsuo Basho

The butterfly is perfuming

“Lighting one candle” by Buson

Lighting one candle

With another candle;

An evening of spring. (Trans. by Blyth, 1949/1981, p. 113).

“A Mountain Path” by Sogi

A mountain path;

Wild geese in the clouds,

The voice of mandarin ducks in the ravine. ( Trans. by R.H. Blyth, 1963, p.47)

Courtesy: Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1918. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36742” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes

Wild Geese

Konna yo ga

mata mo arō ka

tsuki ni kari

Will there ever again

be such a marvelous night!

Wild geese against the moon.

—Trans. John T. Carpenter

“The full moon on the eighth month of the lunar calendar, the peak of autumn, has always been special to East Asian poets. Both the poem and image here capture the moment when wild geese are seen flying across the full moon.” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City).

To view flora, fauna, and landscapes by Hiroshige please open the link here: Landscapes, Flora, and Fauna.

“In this print, one of Harunobu’s most poetic images, a nymphlike beauty dressed in an elegant kimono stands holding a lantern and gazing dreamily at the plum blossoms. The image of admiring plum blossoms at night is a classical theme in the East Asian poetic tradition, and Harunobu’s lyrical rendition has much in common with the art of the Heian period (794–1185). The stylized shape of the cloud at the top of the print reinforces the classical references. Harunobu and his patrons from the elite merchant and samurai classes in the capital, Edo (now Tokyo), admired the literary and cultural tradition of Kyoto, which was the capital during the Heian period.

In this print the artist applied one of the techniques of embossing uncolored areas. To emphasize their softness, the inner layers of the kimono and tabi socks worn by the woman are raised on the paper.”

Courtesy: Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1918. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36725” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Haiku by Santōka Taneda

Snow

Falls on snow—

Silence.

“The Cranes” by John Gould Fletcher (from Japanese Art, 1918)

The cranes have come back to the temple,

The winds are flapping the flags about,

Through a flute of reeds

I will blow a song.

gutenberg.org/cache/epub/27199/pg27199.txt

“Winter Solitude” by Basho (Translated by Robert Hass)

Winter solitude—

a world of one color

the sound of wind

Courtesy: By Utagawa Kunisada – Image: http://collections.lacma.org/sites/default/files/remote_images/piction/ma-31786650-O3.jpgGallery: http://collections.lacma.org/node/190662 archive copy, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27218095

“Passing through this world” by Sogi

Passing through this world,

We shelter as we may

From the winter rain (translated by R.H. Blyth, 1964, p.51).

“The Wind Whistles” by Onitsura

The wind whistles

In the sky;

Winter peonies. (translated by R.H. Blyth, 1964, pp. 96-97).

Courtesy: Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of the Friends of Arthur B. Duel. “https://hvrd.art/o/206730” is in the Public Domain.

From: Haiku in English : Suggestions for Beginners and Others by J.W. Hackett, 1964 in Harold B. Henderson, 1967, pp. 60-61

Life is the found of the haiku experience. So take note of the present moment.

- Remember that haiku is a poetry of everyday life, and that the commonplace is its province.

- Contemplate natural objects closely.,..unseen wonders will reveal themselves.

- Identify (interpenetrate) with your subject, it may be “That are Thou.”

“On the mountain road” by Basho

On the mountain-road

There is no flower more beautiful

Than the wild violet.

From Japanese Haiku (p.71).

“New Year’s Day” by Hattori Ransetsu

New Year’s Day—

The clouds are gone and sparrows

Are telling each other tales.

“Double Cherry Blossoms” by Masaoka Shiki

Double cherry blossoms

Flutter in the wind

One petal after another.

“Evening Snow Falling” by Masaoka Shiki

Evening snow falling,

a pair of mandarin ducks

on an ancient lake.

“Mandarin Ducks” by Yosa Buson

Mandarin ducks,

The extreme of beauty;

The winter wood. (Trans. by Blyth, 1963, p. 278)

“A Mountain Path” by Sogi

A mountain path;

Wild geese in the clouds,

The voice of mandarin ducks in the ravine. (Translated by R.H. Blyth, 1963, p. 47).

Ohara Koson (1877-1945). Mandarin Ducks and Snow (1935). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, United States. Courtesy: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Felix Juda (M.73.37.402). “https://collections.lacma.org/node/190531” is in the Public Domain.[/caption]

Ohara Koson (1877-1945). Mandarin Ducks and Snow (1935). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, United States. Courtesy: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Felix Juda (M.73.37.402). “https://collections.lacma.org/node/190531” is in the Public Domain.[/caption]

Courtesy: By Claude Monet – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=506301

Courtesy: Gift of Stephen Mazoh and Purchase, Bequest of Gioconda King, by exchange, 2008. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438156” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

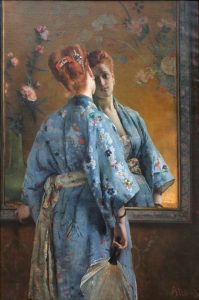

Courtesy: By Alfred Stevens – Ophelia2, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14882567

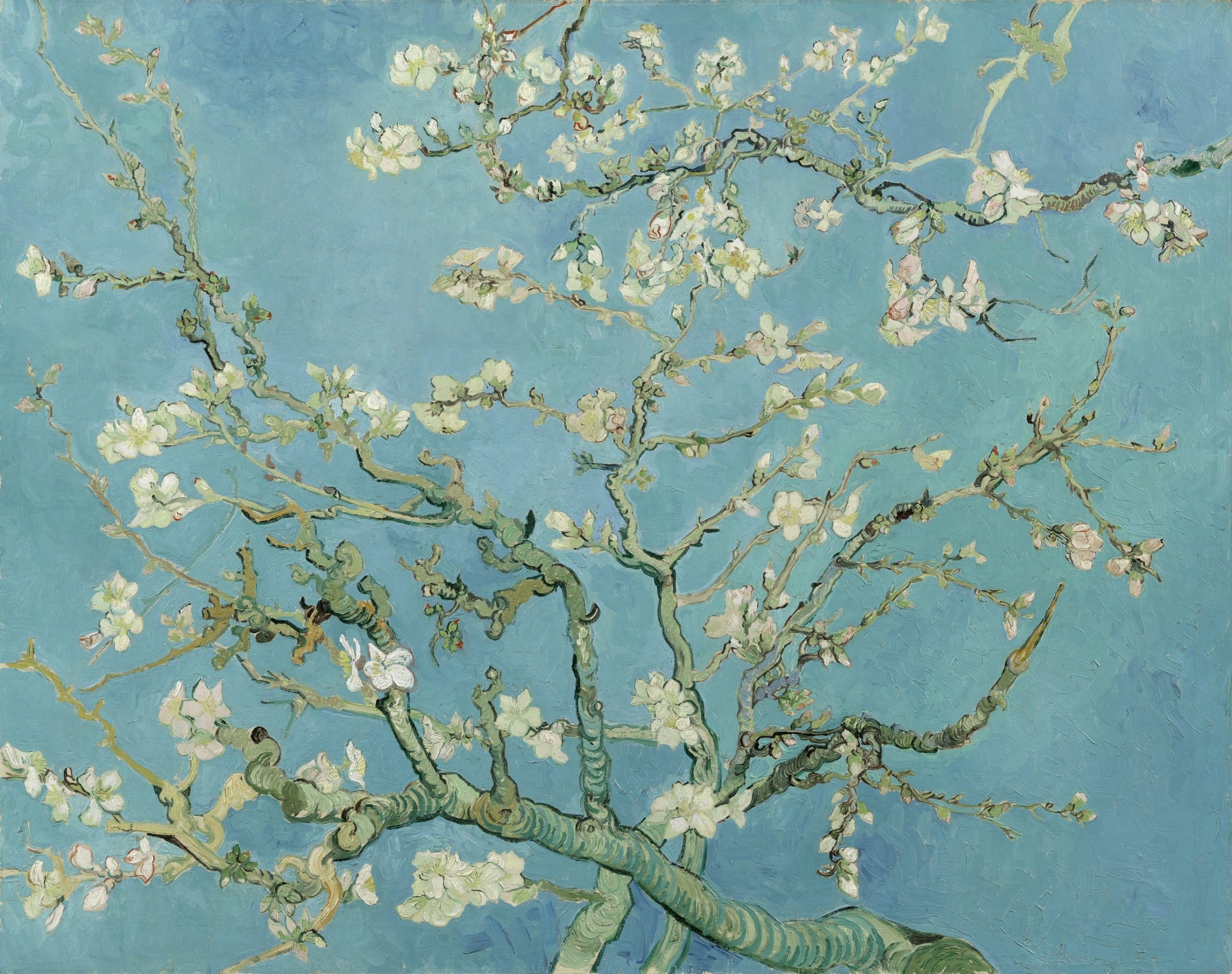

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – dAFXSL9sZ1ulDw at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21977493

To read more about Japanese Influences on Western Art please open the link here.

Courtesy: By Paul Gauguin – nAHq1cbXN_aFlg at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21856031

Courtesy: By Kitagawa Utamaro – http://www.asianart.com/articles/rubin/1.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=625473

References

Addiss, S., Yamamoto, F., & Yamamoto, (2003). A haiku garden: The four seasons in poems and prints. Weatherhill.

Addisss, S. , Yamamoto, F.Y., & Yamamoto, A. Y. (2007). Haiku: An anthology of Japanese poems. Shambhala Library.

Boger, B. H. (1964). The traditional arts of Japan: A complete illustrated guide. Bonanza Books.

Cawthorne, N. (2006). The art of Japanese prints. Bounty Books. (first published in 1997 by Hamlyn).

Honda, H.H. (1956). One hundreds poems from one hundred poets. The Hokuseido Press.

Howard, K. (Ed.) (1994/2006) (2nd edition). The Metropolitan museum of art guide. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Illing, Richard. (1980). The Art of Japanese Prints. London

Blyth, R.H. (1949/1981). Haiku Volume 1: Eastern culture. Hokuseido Press.

Blyth, R.H. (1964). A history of Haiku in two volumes. The Hokuseido Press.

Cawthorne, N. (1997).The art of Japanese prints. Bounty Books.

Cobb, D. (2002). Haiku: The poetry of nature. Universe Pub.

Donegan, P. (2010). Haiku mind: 108 poems to cultivate awareness and open your heart. Shambhala Publ.

Fahy, E., & Grossman, (1982). Metropolitan flowers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gookin, F. (1911). The Project Gutenberg EBook of Japanese Colour-Prints and Their Designers, 2013, Japan Society, New York

Henderson, H.G. (1967). Haiku in English. Charles E. Tuttle Company.

Kanada, Margaret Miller. (1989). Color woodblock printmaking: The traditional method of Ukiyo-e. Shufunotomo.

Larrabee, H. (2020). Haiku illustrated. Amber Books.

Lowenstein, T. Haiku inspirations: Poems and meditations on nature and beauty. Duncan Baird Publishers.

Mason, P. (2004). History of Japanese art. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Marks, A. (2021) Masterpieces of Japanese woodblock printing from Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga. Taschen.