12.7 Ekphrastic and Imagist Poetry with Related Visual Art

Emily Fragos (2012) describes ekphrasis as the response a poet gives to produce a poetic text inspired by a visual work of art. “When a poet responds with his or her own art to a work of visual art-applying speech to what is silent—the resulting poem is termed ekphrastic, from the Greek “ek” meaning “out of” and phrasis meaning “speech” or “expression”.” (Emily Fragos, 2012, p. 2 , Art and Artists. Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets). Vivid details of a particular scene or person in the painting are poetically described. In this section, you will find selected poems that are in direct response to a particular painting. Examples of imagist poems based on paintings are also included.

To read more about Ekphrastic Poetry please open the link here.

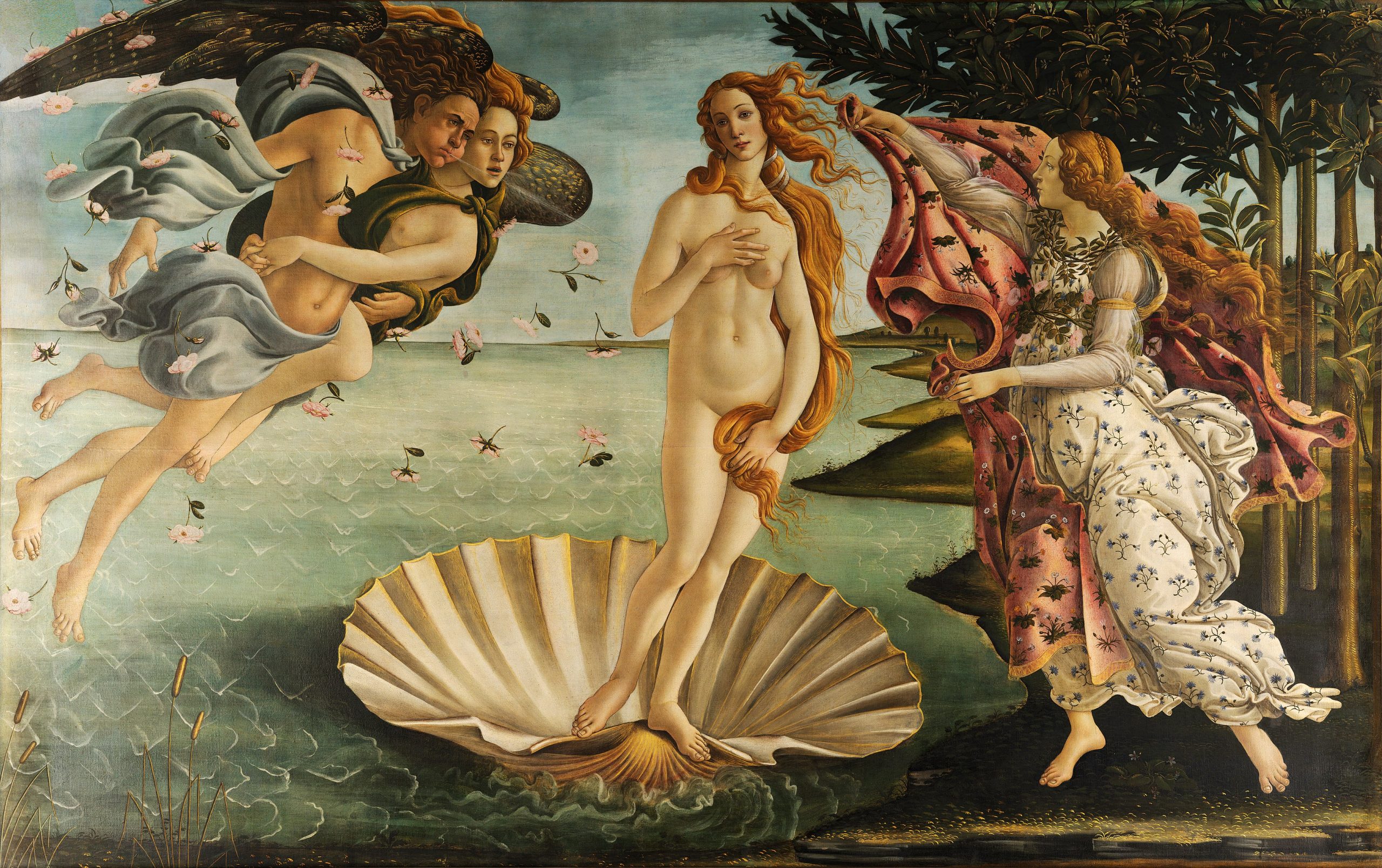

Courtesy: By Sandro Botticelli – Adjusted levels from File:Sandro Botticelli – La nascita di Venere – Google Art Project.jpg, originally from Google Art Project. Compression Photoshop level 9., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22507491

“Venus Transiens” by Amy Lowell

Further Reading

To read “Botticelli, Beyond the Renaissance” by Karen Rosenberg (2023) please open the New York Times link here.

“For Spring by Sandro Botticelli” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

WHAT masque of what old wind-withered New-Year

Honours this Lady? Flora, wanton-eyed

For birth, and with all flowrets prankt and pied:

Aurora, Zephyrus, with mutual cheer

Of clasp and kiss: the Graces circling near,

‘Neath bower-linked arch of white arms glorified:

And with those feathered feet which hovering glide

O’er Spring’s brief bloom, Hermes the harbinger.

Birth-bare, not death-bare yet, the young stems stand

This Lady’s temple-columns: o’er her head

Love wings his shaft. What mystery here is read

Of homage or of hope? But how command

Dead Springs to answer? And how question here

These mummers of that wind-withered New-Year.

“For an Annunciation, Early German” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

The lilies stand before her like a screen

Through which, upon this warm and solemn day,

God surely hears. For there she kneels to pray

Who wafts our prayers to God—Mary the Queen

She was Faith’s Present, parting what had been

From what began with her, and is for aye.

On either hand, God’s twofold system lay:

With meek bowed face a Virgin prayed between.

So prays she, and the Dove flies in to her,

And she has turned. At the low porch is one

Who looks as though deep awe made him to smile.

Heavy with heat, the plants yield shadow there;

The loud flies cross each other in the sun;

And the aisled pillars meet the poplar-aisle.

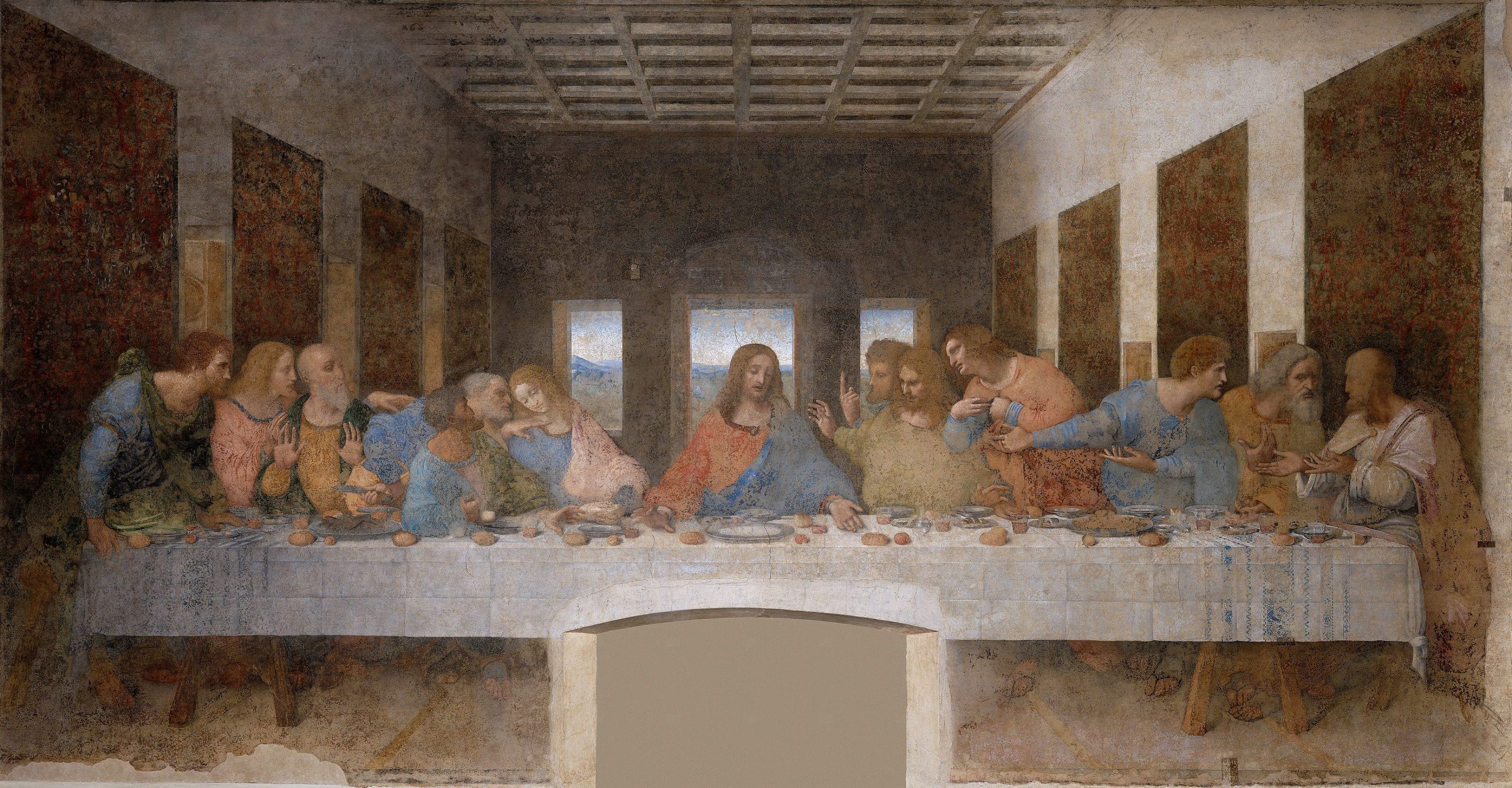

Courtesy: By Leonardo da Vinci – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24759

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

Poem by Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938)

The heaven of the supper fell in love with the all.

It filled it with cracks. It fills them with light.

It fell into the wall. It shines out there

In the form of thirteen heads.

And that’s my night sky, before me

And I’m the child standing under it,

My back getting cold, an ache in my eyes,

And the wall-battering heaven battering me.

At every blow of the battering ram

Stars without eyes rain dow,

New wounds in the last supper

The unfinished mist on the wall.

(From: Fragos, E. (Ed.), (2012). Art and artists: Poems. Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets.)

“Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

near

the edge of the sea

concerned

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

insignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning.

Courtesy: By Pieter Brueghel the Elder – 1. Web Gallery of Art2. The Bridgeman Art Library, Object 3675, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11974918

Early 20th century Imagist poets like Amy Lowell, Hilda Doolittle, and Ezra Pound were known for their elegant use of visual images, clarity of expression, and precision of words. Imagist poems were influenced by Greek lyricists and Japanese Haiku poets. There was a shift away from sentiment and detailed moral and romantic reflections evident in longer Romantic and Victorian verse. Imagist poems tended to be shorter and composed of free verse. Concrete details replaced abstractions. The Imagist movement in poetry influenced the wave of Modernist poets that followed

Exploration: As you read the poems and view the images, identify and write down some of the specific visual images that correspond with words from the poem. Does the poem enhance your appreciation of the work of art? Please also refer to the links here and here.

“On Carpaccio’s Picture: The Dream of St. Ursula” by Amy Lowell (1874-1925)

Swept, clean, and still, across the polished floor

From some unshuttered casement, hid from sight,

The level sunshine slants, its greater light

Quenching the lttle lamp which pallid, poor,

Flickering, unreplenished at the door

Has striven against darkness the long night

Dawn fills the room, and penetrating, bright

The silent sunbeams through the window pour.

And she lies sleeping, ignorant of Fate,

Enmeshed in listless dreams, her soul not yet

Ripened to bear the purport of this day.

The morning breeze scares te coverlet

A shadow falls across the sunlight; wait?

A lark is singing as he flies away.”

Additional Resource: Fragos, E. (2012).Art and Artists: Poems. New York: Everyman’s Library (p. 64).

“The Dance” by William Carlos Williams (1883-1963)

In Brueghel’s great picture, The Kermess,

The dancers go round, they go round an

Around, the squeal and the blare and the

Tweedled of bagpipes, a bugle and fiddles

Tipping their bellies (round as the thick-

Sides glasses whose wash they impound)

Their hips and their bellies off balance

To turn them. Kicking and rolling

About the Fair Grounds, swinging their butts, those

Shanks must be sound to bear up under such

Rollicking measures, prances as they dance

In Brueghel’s great picture, The Kermess.

The Elgin Marbles

The Elgin or Parthanon marbles (designed by the artist Pheidias and which took until 432 BC to complete) are ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon (temple built to worship the goddess Athena) in Athens, Greece. The marbles depicted complex tapestries of the Athenian mythological universe of deities, mythic monsters, heroes, and humans. In 1800, Lord Elgin (British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire) removed the marbles and re-located them to London where they have been on permanent display since 1817. Over the decades, there has been has been an ongoing dispute over the presence of the

marbles in the British Museum in London. Noting their exceptional cultural and artistic importance to the Greek people, the Greek government has asked the UK government to return the marbles to Greece. The acquisition of the marbles and their display in the British Museum has been the focus of international attention and criticism; discussions between the Greek and British governments.

Resources: To learn more about the Elgin marbles and the controversy, please open the link here and here.

To learn more about the history of the Parthanon/Elgin Marbles, please open the link here

“On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” by John Keats

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

Yet ’tis a gentle luxury to weep

That I have not the cloudy winds to keep

Fresh for the opening of the morning’s eye.

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an undescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old time—with a billow.

Wikipedia Note about the Sculpture The Winged Victory of Samothrace (Louvre Museum, Paris, France)

“The Winged Victory of Samothrace (also called the Nike of Samthrace) is a monument that was found on the island of Samothrace, north of the Aegean Sea.t is a masterpiece of Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic era, dating from the beginning of the 2nd century BC. It is composed of a statue representing the goddess Niké (Victory), whose head and arms are missing, and its base is in the shape of a ship’s bow.”

“The Winged Victory” by Bliss Carman

Whose home is the unvanquished sea,

Whose fluttering wind-blown garments keep

The very freshness, fold, and sweep

They wore upon the galley’s prow,

By what unwonted favor now

Hast thou alighted in this place,

Thou Victory of Samothrace?

With eager hearts and striving hands

Strong men in their last need have prayed,

Greatly desiring, undismayed,

And thou hast been across the fight

Their consolation and their might,

Withhold not now one dearer grace,

Thou Victory of Samothrace!

Who wage our strife with Destiny,

And give for Beauty and for Truth

Our love, our valor and our youth.

Are there no honors for these things

To match the pageantries of kings?

Are we more laggard in the race

Than those who fell at Samothrace?

“The Victory of Samothrace” by Rubén Darío (1867-1916) translated by John Holland

The missing head yet of the sacred day

On which, in winds of triumph multitudes

Paraded, inflamed, before the simulacrum

That sent Greeks seething in the Athenian streets…” ( poem excerpt, Fragos, E. (Ed.) (2012), p. 130).

Additional Source: Fragos, E. (2012), Art and Artists (Poems). New York: Everyman’s Library p. 130.

For more information about the poet Ruben Dario (born in Nicaragua), please open the link here.

Courtesy: Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn and Mrs. Alice Lewisohn Crowley, 1946. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/88999” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

“The Mask (for Herman Haller)” by Rainer Maria Rilke

Entering my room this morning,

I had forgotten your presence:

Mask of an oriental woman

Carved by a great sculptor

Sacred terror of finding there,

Where we think we are alone,

More than a face.

And of feeling that my own,

Contemplating you,

Total face,

Could not equal you.

Perspectives for Writing an Ekphrastic Poem: Read Write Think.org (NCTE)

As you begin to write your ekphrastic poems, consider

the following approaches:

*Jot down your impressions; use descriptive words and phrases that highlight the people, animals, and places in the scene.

Consider:

- Write about the scene or subject being depicted in

the artwork. - Write in the voice of a person or object shown in the

work of art. - Write about your experience of looking at the art.

- Relate the work of art to something else it reminds

you of. - Imagine what was happening while the artist was

creating the piece. - Write in the voice of the artist.

- Write a dialogue among characters in a work of art.

- Speak directly to the artist or the subject(s) of the

piece. - Write in the voice of an object or person portrayed in the artwork.

- Imagine a story behind what you see depicted in the piece.

- Speculate about why the artist created this work.

Retrieved June 10, 2023 Readwritethink.org website. https://www.nps.gov/common/uploads/teachers/lessonplans/Poetry%20Prompts.pdf

https://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/ekphrasis-using-inspire-poetry

Your Turn: Write an Ekphrastic or Imaginist Poem based on one of the following art images:.

Courtesy: By Henry Raeburn – National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, online collection, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=715320

You can explore different websites to find a poem you can

write about here.

500 paintings that inspired writers here.

Key Takeaways

Essentials of Great Poetry by Richard Aldington

In the preface to the 1915 edition, Richard Aldington writes about six “essentials of great poetry.” His ideas can be applied to poetry today:

- To use the language of common speech, but to employ always the exact word, not the nearly-exact, nor the merely decorative word.

- To create new rhythms—as the expression of new moods—and not to copy old rhythms, which merely echo old moods. We do not insist upon “free-verse” as the only method of writing poetry….We believe that the individuality of a poet may often be better expressed in free-verse than in conventional forms. In poetry, a new cadence means a new idea.

- To allow absolute freedom in the choice of subject. It is not good art to write badly about aeroplanes and automobiles; nor is it necessarily bad art to write well about the past. We believe passionately in the artistic value of modern life, but we wish to point out that there is nothing so uninspiring nor so old-fashioned as an aeroplane of the year 1911.

- To present an image (hence the name: “Imagist”). We are not a school of painters, but we believe that poetry should render particulars exactly and not deal in vague generalities, however magnificent and sonorous. It is for this reason that we oppose the cosmic poet, who seems to us to shirk the real difficulties of his art.

- To produce poetry that is hard and clear, never blurred nor indefinite.

- Finally, most of us believe that concentration is of the very essence of poetry.” (Preface, Imagist Poetry: An Anthology. New York and Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1915).

For more information, please open the link here