11.5 At the Edge of the Tomorrow: Science Fiction Stories and Visionary Art

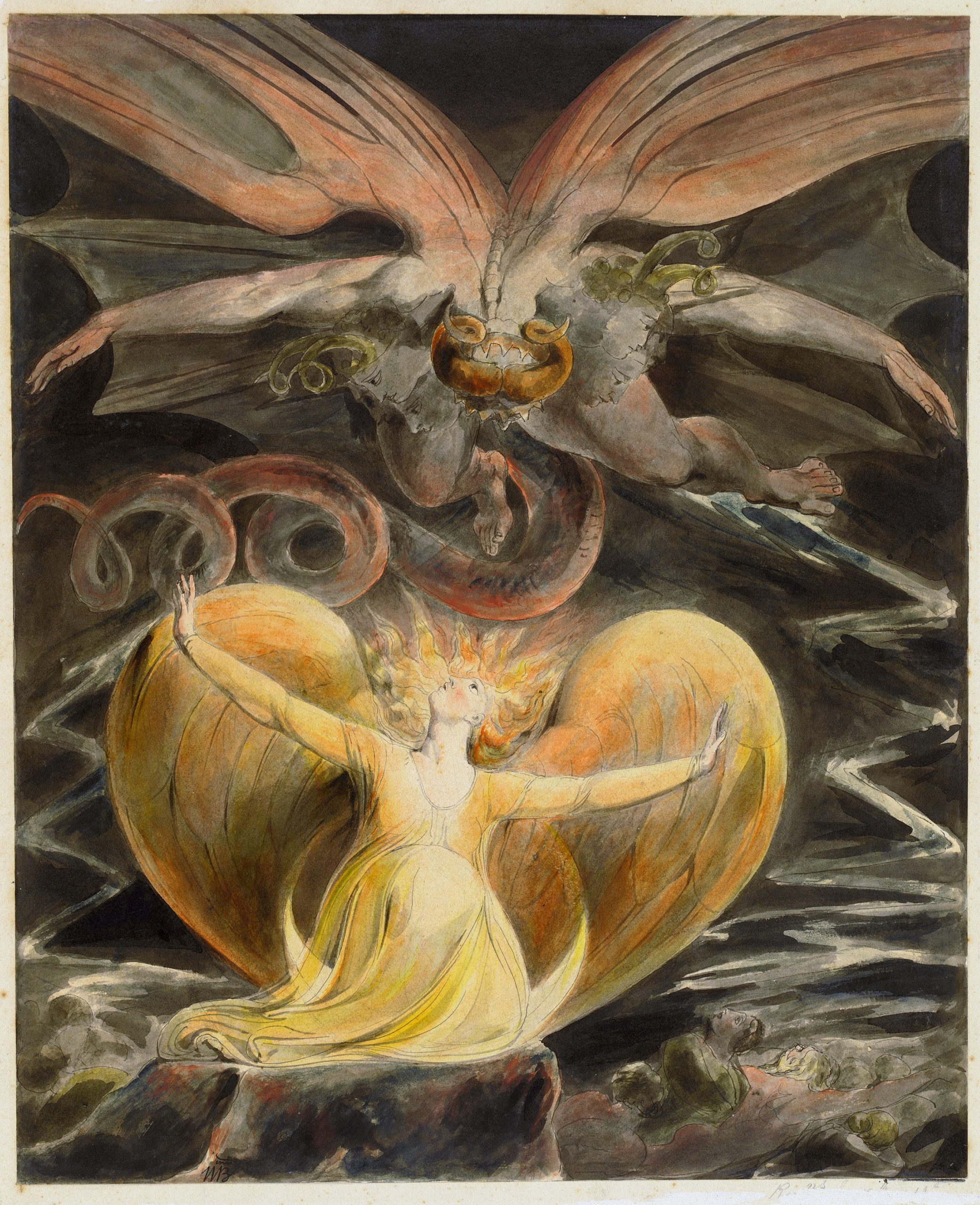

Courtesy: By William Blake – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=147895

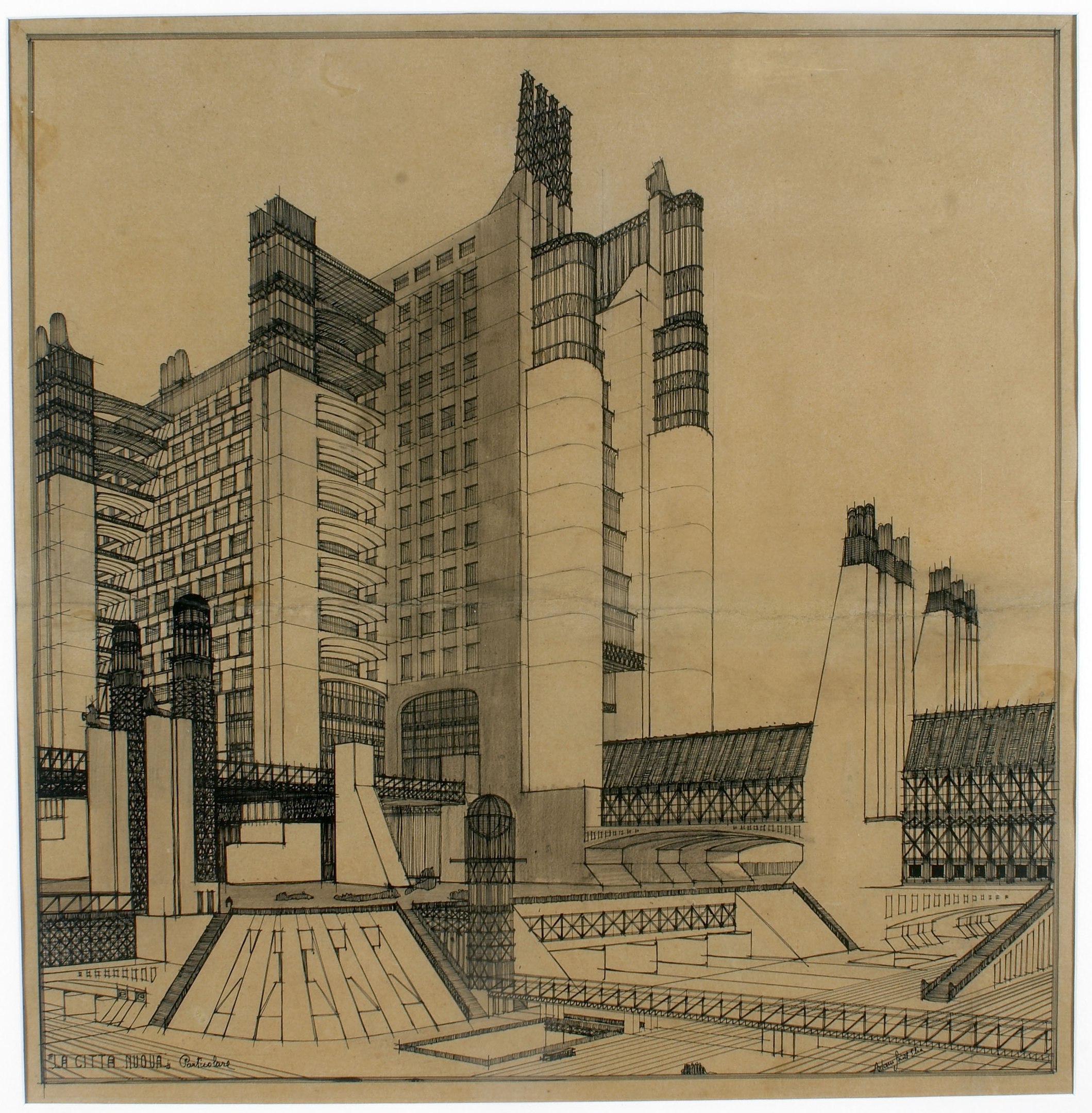

Courtesy: By Antonio Sant’Elia – Utopie metropolitane, la mostra (in Italian). Style & Design. l’Espresso (2013-03-28). Retrieved on 2013-04-01., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25399724

Key Takeaways

Science Fiction writers like Ray Bradbury, Octavia Butler, Isaac Asimov, and Ursula Le Guin present a visionary perspective of what the world might be like in the future. Discussions about robotics, artificial intelligence, sustainable life on other planets, and post-apocalyptic visions of the future can also be explored through art and photography. To what extent will individuals be able to control and manage technology in ways that protect the planet rather than destroy it? How do we envision cities of the future? What role should technology play in our lives? Science Fiction writers often comment on the moral and ethical implications of technologies that have not been fully developed. What role will artificial intelligence play in our lives? Without a moral compass or ethical guidelines, what adverse impact might technology have? Are we in control of technological advances or is technology controlling our lives?

The futuristic setting in many of Ray Bradbury’s stories is bleak and void of nature. Characters find themselves alone and alienated amid a totalitarian system where individual rights and freedoms are by-passed. Conformity takes place over individual freedom of expression and free choice. The dystopian landscapes are void of nature and in stories like “Lenses” by Leah Silverman and “All Summer in a Day” by Ray Bradbury, the earth is no longer habitable and communities seek to re-establish life on other planets. Key themes that emerge from science fiction or speculative fiction include:

- Post-apocalyptic visions of earth/Nuclear Devastation

- The Future

- Technology

- Totalitarian states

- Utopias and Dystopias

- Continuous Surveillance and a loss of individual rights and freedoms

- Rigid Conformity

- Mind/Thought Control

- Parallel Universes

- Time Travel

- Life on Other Planets

- Alien life and Alien Encounters

- The Rise of Artificial Intelligence and Robots

- Biogenetic Engineering

Short Story Excerpts

Excerpt from “The Pedestrian” by Ray Bradbury

Science Fiction story landscapes with accompanying art images

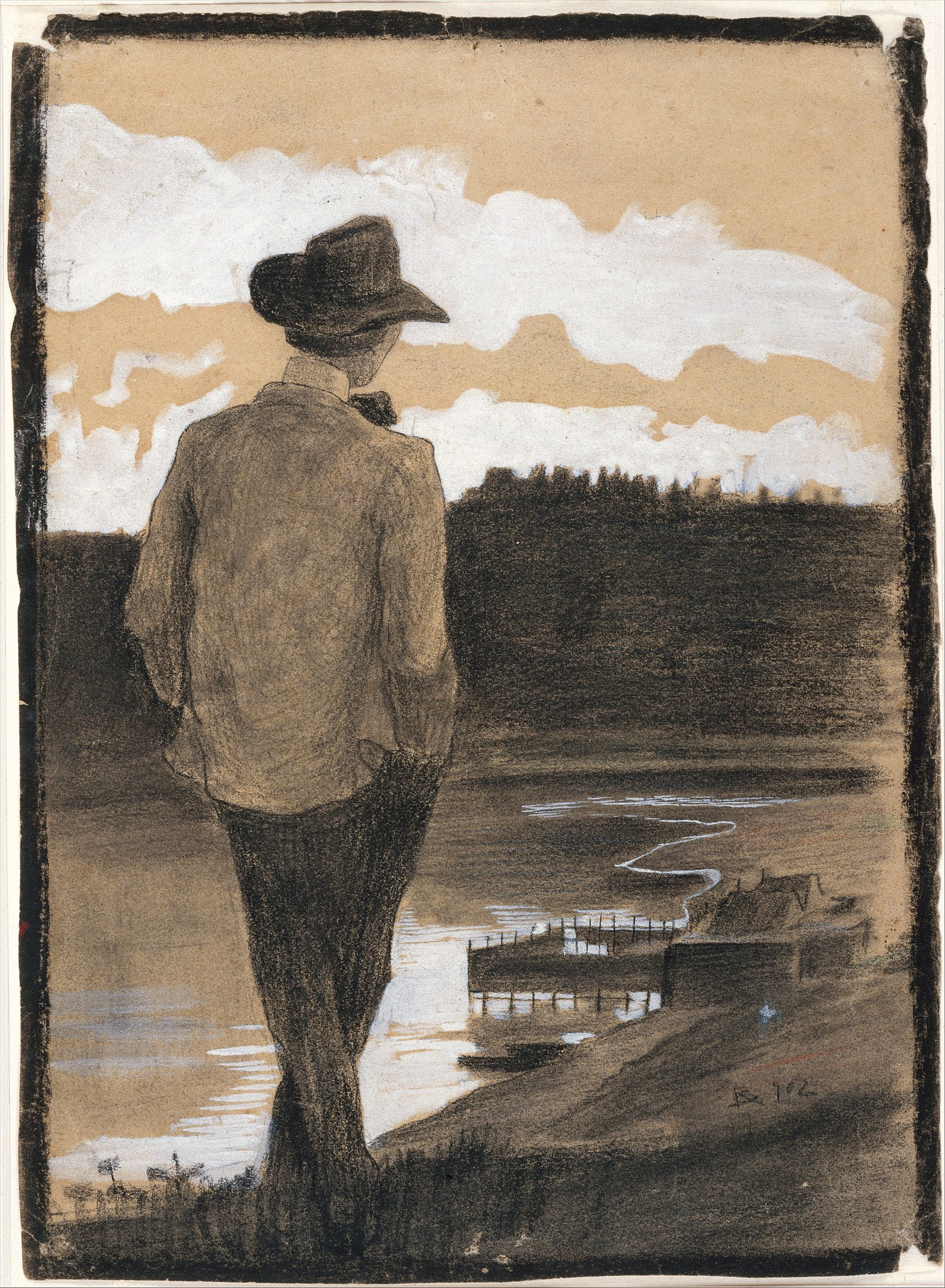

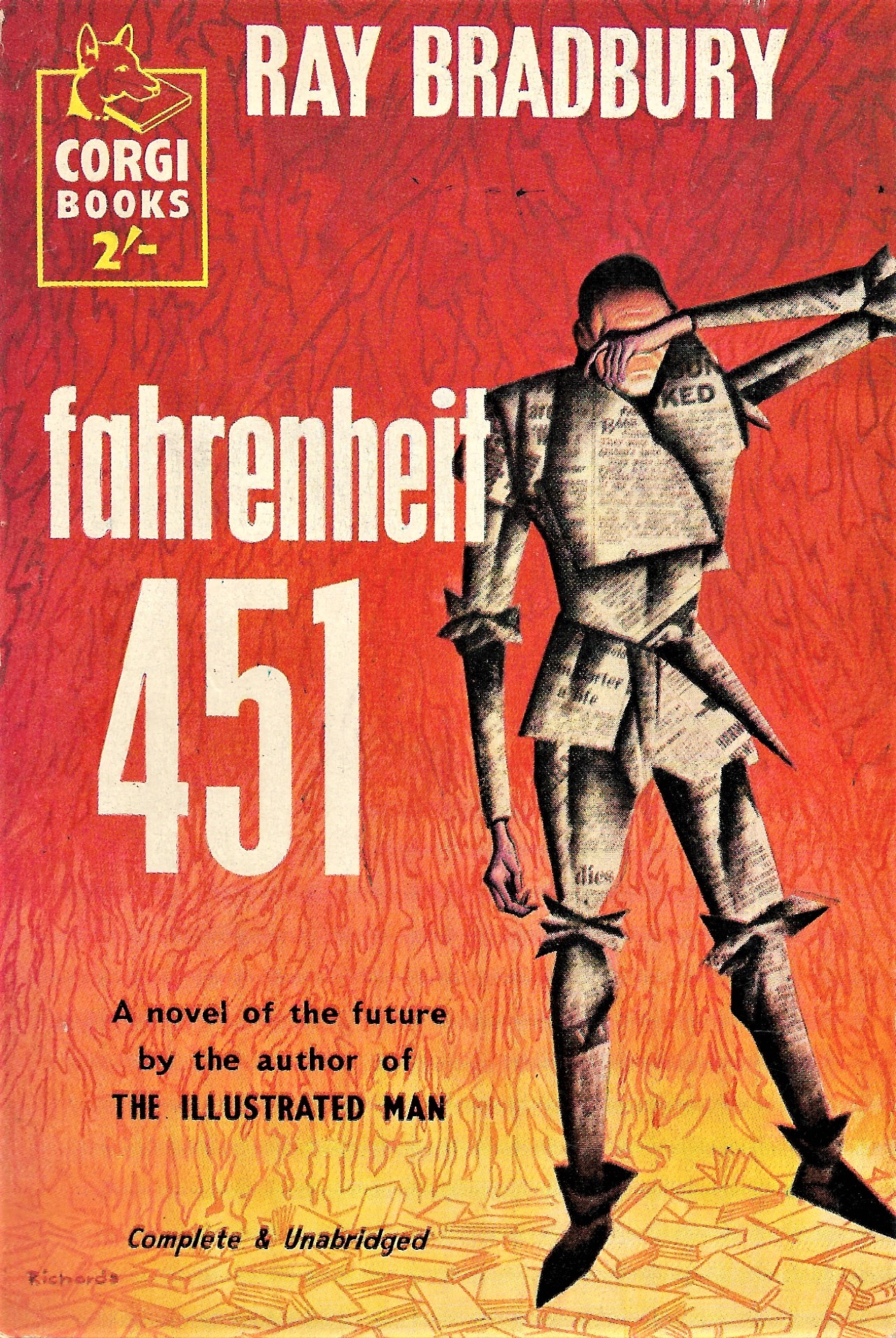

Science fiction writers often make critical observations of governments, human nature, and an adherence to technological advancement over moral and ethical actions. Their critique of societies and human nature is often a prescient warning that in order for world peace and planetary sustainability to exist, individuals, communities, and governments need to re-assess, re-evaluate goals and values, and transform potentially destructive beliefs and actions. Writers like Aldous Huxley (Brave New World), Ray Bradbury (Fahrenheit 451), Arthur C. Clark (2001: A Space Odyssey), Octavia Butler (Parable of the series), and Margaret Atwood (The Handmaid’s Tale) have a visionary sense of what the future world will be like unless significant changes are made that ensure planetary sustainability and human rights. Older adolescents and adult learners can explore the themes that echo in science fiction text and discover their meaning for change today. Ray Bradbury’s (1951) “The Pedestrian” was a catalyst for writing his novel Fahrenheit 451, a bleak look at a totalitarian society that burns books and controls human behavior through the media and propaganda. The setting in “The Pedestrian” is a bleak totalitarian world where around-the-clock surveillance ensures that the people are at home at night in front of their “viewing screens.” Critical thinking, the freedom to read, and even the freedom to go out at night and walk are forbidden. Bradbury’s commentary about the way media has a hypnotic hold over people is as timely in the 21stcentury as it was 70 years ago. Leonard Mead, the hero of Bradbury’s story is a writer and a non-conformist in a society where roles are rigidly stratified and where conformity is a necessity. Those who do not follow the rules are considered deviant and are sent to the “Psychiatric Centre for Research on Regressive Tendencies.” In a world of conformity, Mead is isolated and alone; the sterile and barren setting amplify his own sense of alienation.

Excerpt from “The Pedestrian “by Ray Bradbury

“To enter out into that silence that was the city at eight o’clock of a misty evening in November, to put your feet upon that buckling concrete walk, to step over grassy seams and make your way, hands in pockets, through the silences, that was what Mr. Mead most dearly loved to do. He would stand upon the corner of an intersections and peer down long moonlit avenues of sidewalk in four directions, deciding which way to go, but it really made no different; he was alone in this world of A.D. 2053 or as good as alone, and with a final decision made, a path selected, he would stride off, sending patterns of frosty air before him like the smoke of a cigar…

The street was silent and long and empty, with only his shadow moving like the shadow of a hawk in mid-country. If he closed his eyes and stood very still, frozen, he could imagine himself upon the center of a plain, a wintry, windless American desert with no house in a thousand miles, and only dry riverbeds, the streets, for company.

“What is it now?” he asked the houses, noticing his wrist watch. “Eight thirty p.m.? Time for a dozen assorted murders? A quiz? A revue? A comedian falling off the stage””

Was that a murmur of laughter from within a moon-white house? He hesitated but went on when nothing more happened….In ten years of walking by night or day, for thousands of miles, he had never met another person walking, not once in all that time” (p.601).

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012). Collected short stories. Penguin Books, 2015.

For the complete short story, please open the link here.

“The Veldt” by Ray Bradbury

In “The Veldt” Ray Bradbury cautions individuals about the potentially unhealthy and harmful direction that consumerism and the over-reliance on technology can bring. Practical and critical thinking skills may also be eroded. Rather than being a force that might unite the family together, the children are increasingly alienated from their parents. What happens to the children when the parents allow technology to be like a caregiver and supervisor? The children retaliate against their parents when it is too late… In the story the Peter and Wendy spend time in a hologram- a virtual reality room able to realistically reproduce, in this story, an African veldt—a area of open grassland where animals are roaming. The virtual reality features in the house enable individuals to “create” imaginary spaces. How dependent are individuals to technological devices and diversions? What lure and danger do such dependencies cause? Bradbury conveys his theme in a dramatic story.

Excerpt from “The Veldt” (“The World the Children Made” Ray Bradbury, 1950).

“They stood on the thatched floor of the nursery. It was forty feet across by forty feet long and thirty feet high; it had cost half again as much as the rest of the house.

“But nothing’s too good for our children,” George had said.

The nursery was silent. It was empty as a jungle glade at hot high noon. The walls were blank and two dimensional. Now, as George and Lydia Hadley stood in the center of the room, the walls began to purr and recede into crystalline distance, it seemed, and presently an African veldt appeared, in three dimensions, on all sides, in color reproduced to the final pebble and bit of straw. The ceiling above them became a deep sky with a hot yellow sun.

George Hadley felt the perspiration start on his brow.

“Let’s get out of this sun,” he said. “This is a little too real. But I don’t see anything wrong.”

“Wait a moment, you’ll see,” said his wife.

Now the hidden odorophonics were beginning to blow a wind of odor at the two people in the middle of the baked veldtland. The hot straw smell of lion grass, the cool green smell of the hidden water hole, the great rusty smell of animals, the smell of dust like a red paprika in the hot air. And now the sounds: the thump of distant antelope feet on grassy sod, the papery rustling of vultures. A shadow passed through the sky. The shadow flickered on George Hadley’s upturned, sweating face.”

(Retrieved July 23, 2023. Gothic Digital Series UFSC https://repositorio.ufsc.br/bitstream/handle/123456789/163728/The%20Veldt%20-%20Ray%20Bradbury.pdf)

To read the complete short story, please open the link above.

For more information about this story, please open the Wiki link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Veldt_(short_story)

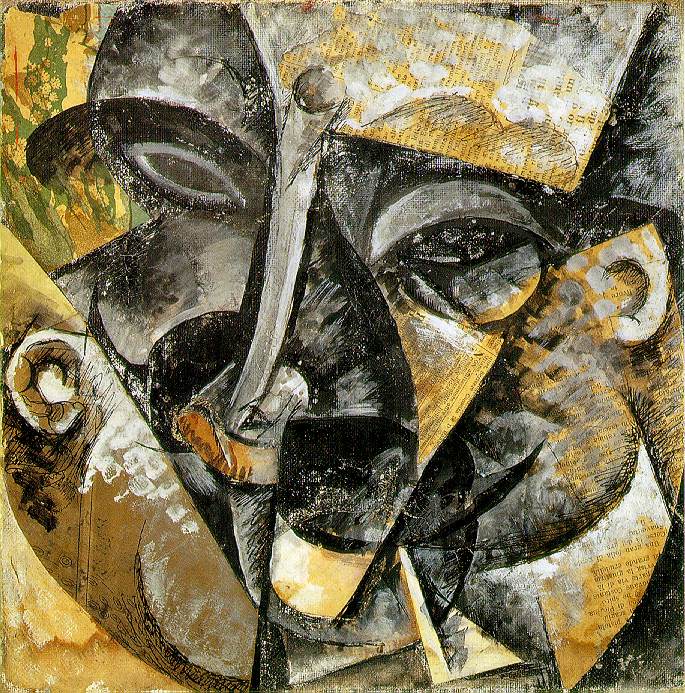

Illustrations for “The Veldt” (1950).

Courtesy: Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/485551” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/485556” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: By Umberto Boccioni – http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/detail.php?ID=10111, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24437397

For more information about the Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni, please open the links below.

Essay: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/umbo/hd_umbo.htm

For more information on Boccioni’s image of futuristic cities, please open the link below.

Illustrating Science Fiction Texts

The Italian illustrator Joseph Muganini (1912-1993) collaborated with Ray Bradbury to produce a series of evocative visual images that complement each scene of “The Pedestrian.” Please open the link below to see these visual images. To what extent can these images help struggling learners understand the elements of fiction? For more information about Joseph Muganini:

http://mydelineatedlife.blogspot.com/2011/11/pedestrian.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Mugnaini

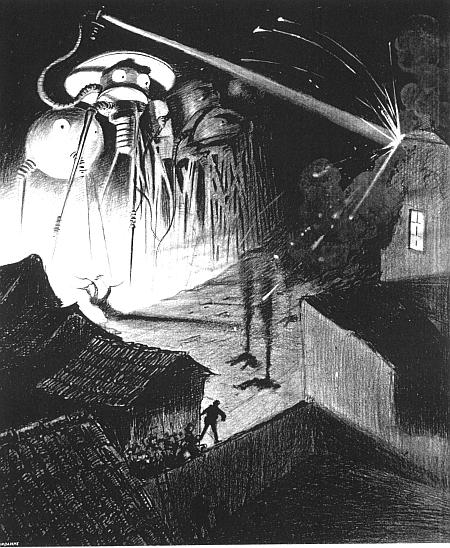

Courtesy: By Henrique Alvim Corrêa – drzeus.best.vhw.net, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5901070

“Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007)

How do you envision cities of the future? What role would government have to ensure social justice and equity? In Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron” equity seems to have been achieved at first glance. As the reader probes further into the totalitarian community described in Vonnegut’s story, we soon realize that individuality is punished and freedom of speech is forbidden. If you have an idiosyncratic talent, you are handicapped in a way that “levels” you with others. Like Bradbury and Le Guin, Vonnegut creates a dystopian setting to highlight his political, social, and cultural critique of contemporary society. Harrison Bergeron is a handsome young man determined to express his own opinions.

A dystopian society similar to that of “Harrison Bergeron” appears in Vonnegut’s 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan. When the Space Wanderer returns to Earth he finds a society in which handicaps are used to make all people equal, eradicating the supposedly ruinous effects of blind luck on human society. The narrator claims that now “the weakest and the meekest were bound to admit, at last, that the race of life was fair.

Excerpt from “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut

“The year was 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

Some things about living still weren’t quite right, though. April for instance, still drove people crazy by not being springtime. And it was in that clammy month that the H-G men took George and Hazel Bergeron’s fourteen-year-old son, Harrison, away.

It was tragic, all right, but George and Hazel couldn’t think about it very hard. Hazel had a perfectly average intelligence, which meant she couldn’t think about anything except in short bursts. And George, while his intelligence was way above normal, had a little mental handicap radio in his ear. He was required by law to wear it at all times. It was tuned to a government transmitter. Every twenty seconds or so, the transmitter would send out some sharp noise to keep people like George from taking unfair advantage of their brains.”

Retrieved Feb. 20, 2023 https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxtc3JlZG1hbmVuZ2xpc2h8Z3g6MjdlZjYzZmNmMjFjMjgxZA

“The Ones who Walked Away from Omelas” by Ursula Le Guin (1929-2018)

The idyllic landscape in Le Guin’s story hides a frightening reality.

Courtesy: By Vladimir Baranov-Rossine – the-athenaeum.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79445849

“The Ones Who Walked Away from Omelas” by Ursula Le Guin (1929-2018).

In this story, Ursula Le Guin creates the imaginary community of Omelas a city “bright towered by the sea.” There is a fairy tale like quality to this shimmering city of light and beauty. Community members seem content and carefree. While the citizens do not have the technological marvels and resources of other places, the people seem sophisticated and cultured. The narrator explains that there are no kings, soldiers, priests, or slaves in Omelas. Life seems abundant as people celebrate festivals and enjoy each others’ company. The utopia idyll is shattered toward the end of the story when the narrator explains that the magnificent splendour of the city is dependent on a scapegoat—an innocent child that is kept in darkness and misery. The citizens of Omelas know that the child is there and they understand that “their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of the skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery”(Le Guin, p. 534). Urusula Le Guin challenges readers to think of the way “advanced” societies with high degrees of material success look away from the reality that their comfort is too often the result of the exploitation and suffering of others. Le Guin’s aim “has been less to imagine alien cultures than to explore humanity” (Gioia & Guinn, p. 531). Le Guin’s stories are concerned with social justice, equity across cultures, genders, and/or races. Like the stories of Asimov, Bradbury, Huxley, and Vonnegut, the themes in her works resonate with our time. While most of the citizens adapt to the injustice and remain in Omelas, others who are horrified and perhaps have more compassion and empathy decide to leave and “go toward a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the one who walk away from Omelas.” (p. 535). Le Guin writes that her story centres upon the psychomyth of the scapegoat. To what extent do the privileges of some depend on the exploitation of others? She draws upon the psychology of William James (1842-1910) who wrote:

Or if the hypothesis were offered us of a world in which Messr. Fourier’s and Bellamy’s and Morris’s utopias should all be outdone, and millions kept permanently happy on the one simple condition, that a certain lost soul on the far-off edge of things should lead a life of lonely torment, what except a specific and independent sort of emotion can it be which would make us immediately feel, even though an impulse arose within us to clutch a the happiness so offered, how hideous a thing would its enjoyment when deliberately accepted as the fruit of this bargain? (p. 536)/ https://catapult.co/leahsilverman

Le Guin explains that the “dilemma of the American conscience” is conveyed by James in this quote. Inspired by both Fyodor Dostoevsky and William James, Le Guin penned her famous story.

Story Excerpt of “The Ones who Walked Away from Omelas” by Ursula Le Guin (1973).

“Far to the north and west the mountains stood up half encircling Omelas on her bay. The air of morning was so clear that the snow still crowning the Eighteen Peaks burned with white-gold fire across the miles of sunlit air, under the dark blue of the sky. There was just enough wind to make the banners that marked the race-course snap and flutter now and then. In the silence of the broad green meadows one could hear the music winding through the city streets, farther and nearer and even approaching, a cheerful faint sweetness of the air that from time to time trembled and gathered together and broke out to the great joyous clanging of the bells.

Joyous! How is one to tell about joy? How describe the citizens of Omelas?

They were not simple folk, you see, though they were happy. But we do not say the words of cheer much anymore. All smiles have become archaic. Given a description such as this one tends to make certain assumptions. Given a description such as this one teds to look next for the King, mounted on a splendid stallion and surrounded by his noble knights, or perhaps in a golden litter bone by great-muscled slaves. But there was no king. They did not use swords, or keep slaves. They were not barbarians. I do not know the rules and law of their society, but I suspect that they were singularily few. As they did without monarchy and slavery, so they also got on without the stock exchange, the advertisements, the secret police, and the bomb. Yet I repeat that these were not simply folk, not dulcer shepherds, bland utopians. They were not less complex than us. ….” (pp. 531-532).

“The Ones Who Walked Away from Omelas” by Ursula Le Guin in Gioia, D., & Gwynn, R.S. (Eds.). The art of the short story. Pearson Longman (pp. 530-536).

For the complete short story, please open the link here.

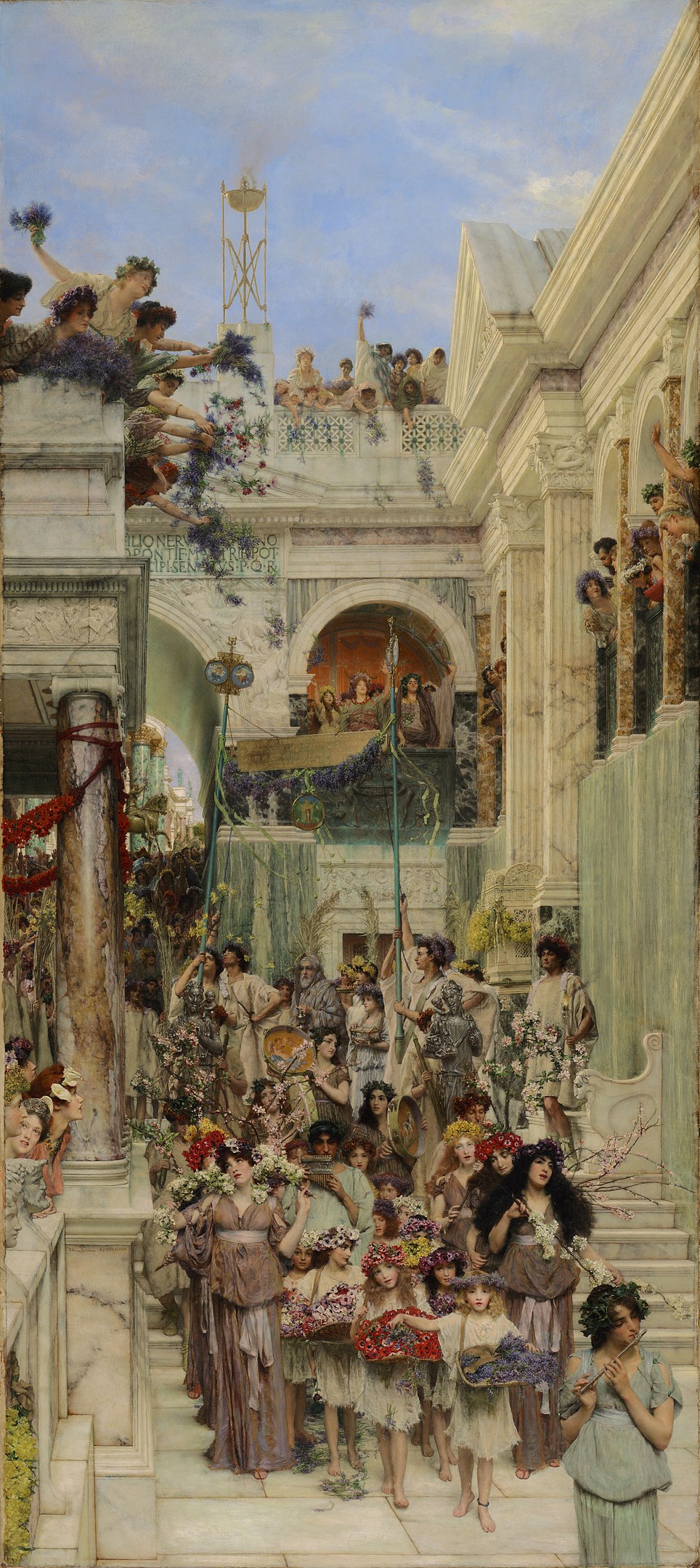

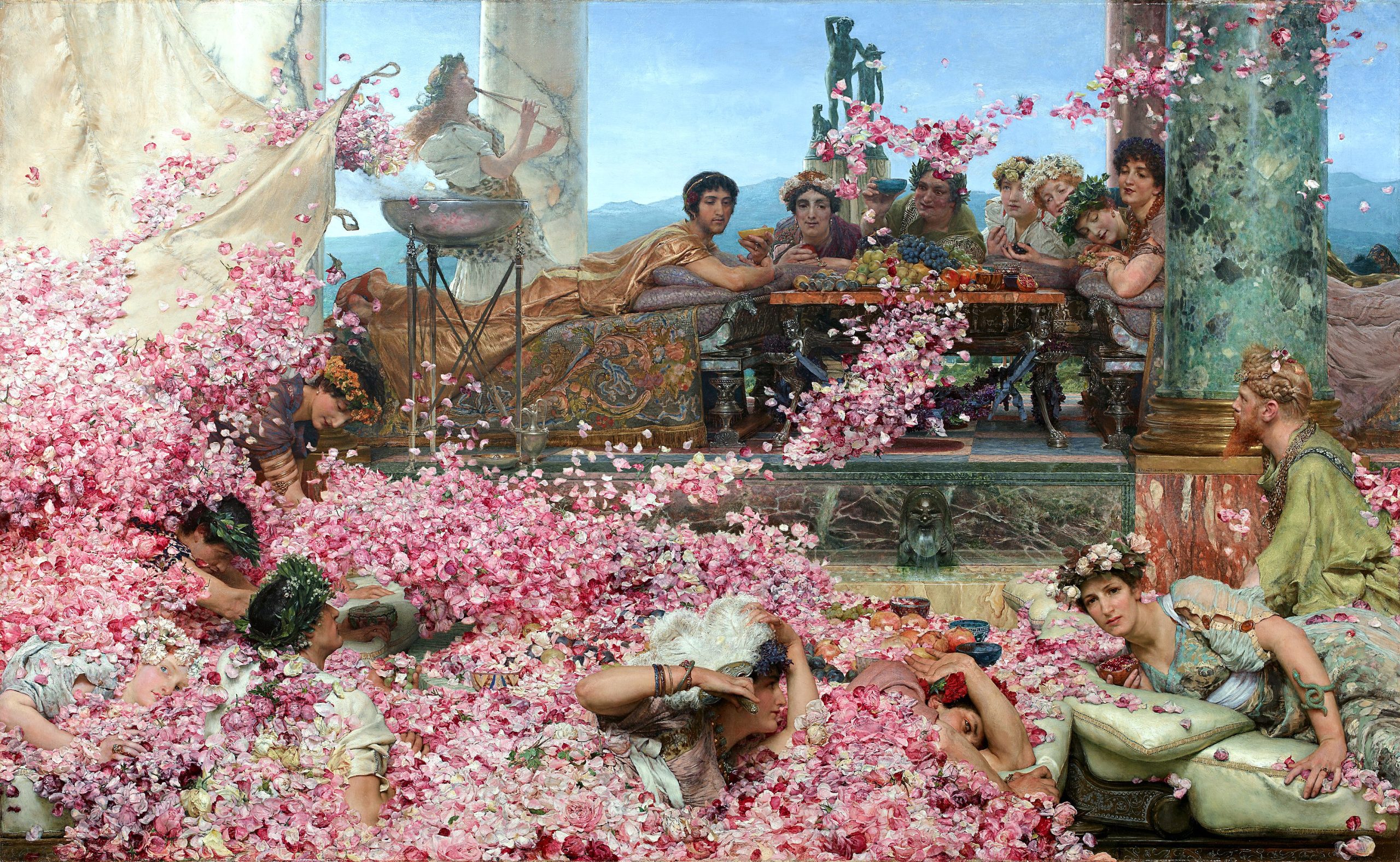

Idyllic Visions in the Art of Lawrence Alma Tadema (1836-1912).

“Omelas sounds in my words like a city in a fairy tale.” (Le Guin, p. 532)

How would you imagine Ursula Le Guin’s fairy-tale like city of Omelas to look?

The 19th century Dutch-British artist Lawrence Alma Tadema draws on ancient myths and the idyllic scenes from ancient Egyptian, Roman, and Greek society to transport viewers to another world. His painting can be a catalyst to imagine the world described in Le Guin’s “Omelas.”

Courtesy: By Lawrence Alma-Tadema – 1. Unknown source2. The Getty Center, Object 680This image was taken from the Getty Research Institute’s Open Content Program, which states the following regarding their assessment that no known copyright restrictions exist:Open content images are digital surrogates of works of art that are in the Getty’s collections and in the public domain, for which we hold all rights, or for which we are not aware of any rights restrictions.While the Getty Research Institute cannot make an absolute statement on the copyright status of a given image, “Open content images can be used for any purpose without first seeking permission from the Getty.”More information can be found at http://www.getty.edu/about/opencontent.html., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=755079

Courtesy: By Lawrence Alma-Tadema – Superb magazine, The Désirs & Volupté exhibition at the Musée Jacquemart-André – direct link, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=755081

For more information about the story of “The Roses of Heliogabulus” please open the link here.

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927). The Enchanted Garden of Messer Ansaldo (1889). Public Domain.

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927). The Enchanted Garden of Messer Ansaldo (1889). Public Domain.

Courtesy: By Marie Spartali Stillman – Pre‑Raphaelite Inc., by courtesy of Julian Hartnoll, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50983208